Biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase from B. xenovorans LB400 and its variants BPDOP4 and BPDORR41 were crystallized using agarose gel and the crystals were characterized using X-ray diffraction.

Keywords: biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase; Burkholderia xenovorans LB400; agarose gel

Abstract

Biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase (BPDO; EC 1.14.12.18) catalyzes the initial step in the degradation of biphenyl and some polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). BPDOLB400, the terminal dioxygenase component from Burkholderia xenovorans LB400, a proteobacterial species that degrades a broad range of PCBs, has been crystallized under anaerobic conditions by sitting-drop vapour diffusion. Initial crystals obtained using various polyethylene glycols as precipitating agents diffracted to very low resolution (∼8 Å) and the recorded reflections were diffuse and poorly shaped. The quality of the crystals was significantly improved by the addition of 0.2% agarose to the crystallization cocktail. In the presence of agarose, wild-type BPDOLB400 crystals that diffracted to 2.4 Å resolution grew in space group P1. Crystals of the BPDOP4 and BPDORR41 variants of BPDOLB400 grew in space group P21.

1. Introduction

The multicomponent biphenyl dioxygenase system (BPDOS) catalyzes the dihydroxylation of an aromatic ring as the first step in the catabolism of biphenyl and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs); in the case of biphenyl, the product is cis-2,3-dihydro-2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl (Seeger et al., 1995a ▶). BPDOS includes an initial NADH:ferredoxin oxidoreductase that reduces a Rieske-type ferredoxin, which in turn delivers electrons to the terminal component biphenyl dioxygenase (BPDO). BPDO is an α3β3 heterohexamer. Each α subunit carries a Rieske-type [2Fe–2S] cluster and a mononuclear Fe site where dioxygenation occurs (Hurtubise et al., 1996 ▶).

Burkholderia xenovorans LB400 is one of the most potent PCB-degrading aerobic microorganisms characterized to date (Bedard et al., 1986 ▶). Its effectiveness is in part a consequence of the relatively broad PCB substrate profile of the BPDO from this species, BPDOLB400 (Haddock et al., 1995 ▶; Seeger et al., 1995b ▶). Nevertheless, BPDOLB400 cannot initiate the degradation of all lightly chlorinated PCBs. Analyses of sequence variations and substrate range among BPDOs (see, for example, Mondello et al., 1997 ▶) have stimulated efforts to expand the PCB range of BPDOLB400 and homologues (Erickson & Mondello, 1993 ▶; Furukawa, 2000 ▶; Barriault et al., 2002 ▶). For example, BPDOP4, which was created from BPDOLB400 via the substitutions T335A and F336M (Barriault & Sylvestre, 2004 ▶), and BPDORR41, which was created from BPDOP4 via the substitutions N338Q, I341V and L409F (Mohammadi & Sylvestre, 2005 ▶), are variants that exhibit a higher turnover for a range of chlorobiphenyls and chlorodibenzofurans that are poorly processed by wild-type BPDOLB400.

We initiated crystallographic studies of BPDOLB400 and these variants in order to establish the structural context of the differences in their biochemical properties.

Many physical or chemical variables and processes may affect the growth and quality of protein crystals (Ducruix & Giegé, 1999 ▶; McPherson, 1999 ▶). Among these are transport processes such as diffusion and convection. For example, convective flow can introduce physical defects and impurities into a protein crystal (McPherson, 1999 ▶). Therefore, the suppression of gravity-induced convection and the establishment of diffusive transport conditions by growth under microgravity (McPherson, 1999 ▶) or in gels (García-Ruiz et al., 2001 ▶) can improve crystals. The growth of protein crystals in agarose (Provost & Robert, 1991 ▶) or silica gels (Robert & Lefaucheux, 1988 ▶; Cudney et al., 1994 ▶) is an established technique. As noted previously, agarose presents several advantages for the crystallization experiment (Provost & Robert, 1991 ▶; Gavira & García-Ruiz, 2002 ▶) and may facilitate cryogenic cooling (Zhu et al., 2001 ▶). Here, we report the beneficial influence of agarose gel on the crystallization of BPDOLB400 and its variants BPDOP4 and BPDORR41.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Protein production and purification

BPDOLB400 (the GenBank accession Nos. for the sequences of the α and β subunits are AAB63425 and AAB63426, respectively) was produced as described previously for the Pandorae pnomenusa B-356 BPDO (BPDOB-356; Gómez-Gil et al., 2007 ▶) using Escherichia coli C41 (DE3) (Miroux & Walker, 1996 ▶) harbouring the isc plasmid and the pT7-6a vector. The BPDOP4 and BPDORR41 variants were produced as recombinant His-tagged proteins in isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside-induced E. coli C41 (DE3) (pET-14b-bpAE; Mohammadi et al., 2007 ▶).

BPDOLB400 was purified anaerobically as described previously for BPDOB-356 (Gómez-Gil et al., 2007 ▶). Accordingly, all preparations were manipulated under an atmosphere of N2 (<2 p.p.m. O2). Chromatography was performed on an ÄKTA Explorer 100 (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Baie d’Urfé, Québec, Canada) interfaced to a glovebox (Vaillancourt et al., 1998 ▶).

The BPDOP4 and BPDORR41 variants were purified by affinity chromatography as described previously (Mohammadi et al., 2007 ▶), except that the resin-bound protein was washed batchwise with 10 mM phosphate pH 7.3 containing 140 mM NaCl and, successively, 20 and 40 mM imidazole. 1000 units of thrombin (GE Healthcare) were then added to the resin slurry and it was incubated for 16 h at room temperature on a rotatory shaker at 0.5 rev min−1. The resin was then removed by filtration using a 0.22 µm filter (Millipore) and the protein solution was washed using a Microcon YM-100 centrifugal filter unit (Millipore) to remove the thrombin and to change the buffer to 25 mM HEPES pH 7.3 containing 0.25 mM ferrous ammonium sulfate, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 10% glycerol for preservation. This protein preparation showed a single peak upon HPLC gel-filtration chromatography.

2.2. Crystallization experiments

For crystallization experiments, buffer components obtained from Sigma and polyethylene glycols obtained from Fluka were used without further purification. All crystallization experiments took place under anaerobic conditions in a N2-atmosphere glovebox (Innovative Technologies, Newburyport, Massachusetts, USA) typically maintained at ≤5 p.p.m. O2. For BPDOLB400, the typical protein sample included BPDO at 12 mg ml−1, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.3, 10% glycerol, 0.25 mM ferrous ammonium sulfate and 2 mM DTT. Initial crystallization conditions were established via the sitting-drop vapour-diffusion method using Crystal Screen and Crystal Screen 2 in 24-well Cryschem plates from Hampton Research (Aliso Viejo, California, USA). Sitting drops were prepared by mixing equal volumes (2 µl each) of the protein and reservoir solutions. Tiny crystals were obtained in the presence of granular precipitate using 20%(w/v) polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000), 0.1 M sodium cacodylate pH 6.5 and 0.2 M magnesium acetate tetrahydrate (Crystal Screen solution No. 18). This lead was explored by varying the pH, the temperature, the nature and concentration of the PEG, common additives (i.e. minor co-solutes) and the protein concentration.

A significant improvement in crystal properties was obtained by adding 0.2%(w/v) agarose to the reservoir solution before combining it with the protein sample. At this concentration, the reservoir solution and the sitting drop remain fluid but are very viscous. The best crystals grew at 294 K when the reservoir solution (1000 µl) consisted of 20–25%(w/v) PEG 8000 or PEG 5000 MME, 50 mM PIPES pH 6.5, 100 mM ammonium acetate, 5%(v/v) glycerol and 0.2%(w/v) agarose. As in the initial screen, the sitting drops were prepared by mixing 2 µl protein solution and 2 µl reservoir solution. Similar procedures were used to crystallize the variants, but the protein concentration was 8 mg ml−1 and successful crystallization only occurred at pH 6.5.

2.3. Measurement and analysis of diffraction data

Crystals were frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen and preserved in a cryogenic N2-gas stream (∼100 K) during diffraction experiments. Cryo-stabilization of the crystals is discussed in §3. Diffraction data were acquired using X-rays from a standard Cu rotating-anode generator and using synchrotron radiation. In the former case, the instrumentation included a 5 kW Rigaku rotating-anode generator, a Rigaku/MSC R-AXIS IV++ imaging-plate detector, Rigaku/MSC multilayer optics and an Oxford cryogenic crystal-cooling device. In the latter case, we used the facilities of BioCARS beamline 14-ID and SER-CAT beamline 22-ID at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, USA. Diffraction images and intensities were processed and scaled using the HKL-2000 suite (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶).

3. Results and discussion

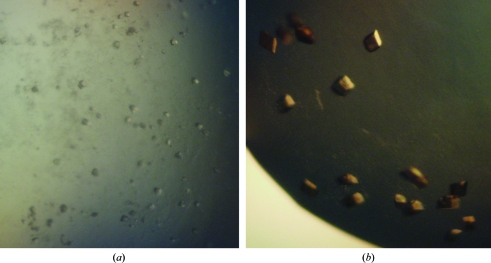

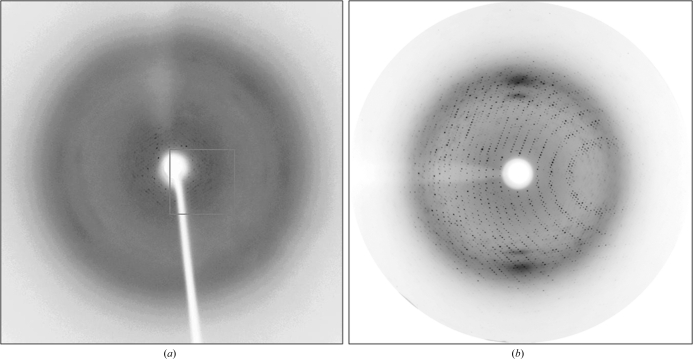

The initial crystals (without agarose) appeared after 24 h and grew to maximum dimensions of 0.1 × 0.005 × 0.005 mm in two weeks (Fig. 1 ▶ a). They produced no Bragg diffraction when mounted in capillaries. A quick (<10 s) immersion of the crystals into a sample of the reservoir solution supplemented with 20%(v/v) glycerol produced a low-resolution (8 Å) diffraction pattern (Fig. 2 ▶ a). Many other approaches to cryostabilization were attempted and resulted in inferior or no diffraction. We were unable to improve the crystals by altering key variables or by the use of common additives. At best, showers of poor-quality crystals were obtained from 0.1 M MES or PIPES pH 6.0–6.5, 20–25%(w/v) PEG 8000, 6000 or 5000 MME and 8 mg ml−1 protein at 294 K.

Figure 1.

Crystals of biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase from B. xenovorans LB400. (a) Crystals of BPDOLB400 grown without agarose. The longest dimension of a typical crystal is between 20 and 30 µm. (b) Crystals of BPDOLB400 grown with agarose. The longest dimension of a typical crystal is between 50 and 100 µm.

Figure 2.

Diffraction of BPDOLB400 crystals. (a) Diffraction of crystals grown without agarose. Bragg reflections were observed to 8 Å resolution. (b) Diffraction of crystals grown with agarose. Bragg reflections were observed to 2.2 Å resolution.

Crystals grown in the presence of agarose took more than 3 d to appear and were ultimately larger and better shaped (Fig. 1 ▶

b) compared with crystals grown without agarose. For example, the crystal used to produce the data described below grew to dimensions of 0.3 × 0.2 × 0.1 mm within 10–15 d. We also observed a decrease in the number of intergrown crystals or crystals with surface defects. Moreover, crystals grown in the presence of agarose remained physically intact throughout serial transfer into solutions containing samples of the reservoir solution supplemented with increasing concentrations of glycerol (10, 15 and 20%) and flash-freezing by direct immersion in liquid nitrogen. The frozen crystals diffracted X-rays from the Cu rotating-anode generator to 2.8 Å resolution. Two crystal forms belonging to space group types P1 and P21 diffracted to 2.4 and 2.2 Å resolution, respectively, using synchrotron radiation (Table 1 ▶, Fig. 2 ▶

b). BPDOLB400 (wild-type) crystals belonged to the triclinic space group type P1, with unit-cell parameters a = 132.8, b = 132.6, c = 130.4 Å, α = 102.7, β = 101.1, γ = 105.3°. Although the unit-cell parameters suggested the possibility of a rhombohedral space group, analysis of the diffraction data under the assumption of Laue group  gave an R

merge of 0.44. The crystals of the BPDOP4 and BPDORR41 variants belonged to the monoclinic space group type P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 86.7, b = 276.8, c = 93.3 Å, β = 117.4°. For the P1 crystals (wild type), analysis of the probable protein and solvent content of the unit cell suggested the possibility of four α3β3 hexamers in the unit cell with a Matthews coefficient V

M (Matthews, 1968 ▶) of 2.41 Å3 Da−1 and a solvent content of 50%. The P21 crystals of the variants can accommodate four hexamers in the unit cell with a Matthews coefficient V

M of 2.27 Å3 Da−1 and a solvent content of 46%.

gave an R

merge of 0.44. The crystals of the BPDOP4 and BPDORR41 variants belonged to the monoclinic space group type P21, with unit-cell parameters a = 86.7, b = 276.8, c = 93.3 Å, β = 117.4°. For the P1 crystals (wild type), analysis of the probable protein and solvent content of the unit cell suggested the possibility of four α3β3 hexamers in the unit cell with a Matthews coefficient V

M (Matthews, 1968 ▶) of 2.41 Å3 Da−1 and a solvent content of 50%. The P21 crystals of the variants can accommodate four hexamers in the unit cell with a Matthews coefficient V

M of 2.27 Å3 Da−1 and a solvent content of 46%.

Table 1. Experimental parameters and diffraction statistics for biphenyl 2,3-dioxygenase from B. xenovorans LB400 and its variants (BPDOP4 and BPDORR41).

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| P1 type | P21 type | |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature (K) | 100 | 100 |

| Crystal dimensions (µm) | 300 × 30 × 20 | 250 × 100 × 40 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.000 | 0.9000 |

| Beam | 0.13 × 0.34 mm | SER-CAT 22-ID |

| Detector | ADSC Quantum 315 | MAR CCD |

| α3β3 hexamers per cell | 4 | 4 |

| VM (Å3 Da−1) | 2.41 | 2.27 |

| Solvent content (%) | 50.0 | 46.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0–2.4 (2.5–2.4) | 50.0–2.2 (2.3–2.2) |

| No. of reflections | 802465 | 530411 |

| No. of unique reflections | 294357 | 147337 |

| Completeness (%) | 95.0 (86.0) | 90.0 (64.0) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 9.8 (2.0) | 9.7 (2.0) |

| Redundancy | 3.8 (2.4) | 4.5 (2.7) |

| Rmerge† (%) | 9.0 (29.0) | 8.0 (26.4) |

R

merge =

, where I

i(hkl) is the ith observation of reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the weighted average intensity for all observations i of reflection hkl.

, where I

i(hkl) is the ith observation of reflection hkl and 〈I(hkl)〉 is the weighted average intensity for all observations i of reflection hkl.

Acknowledgments

Use of the BioCARS Sector 14 at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources under grant No. RR007707. Additional X-ray diffraction data were collected at APS using the Southeast Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) 22-ID beamline; supporting institutions may be found at http://www.ser-cat.org/members.html. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38. Part of this work was supported by Discovery and Strategic grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) to MS and LDE.

References

- Barriault, D., Plante, M. M. & Sylvestre, M. (2002). J. Bacteriol. 184, 3794–3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Barriault, D. & Sylvestre, M. (2004). J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47480–47488. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bedard, D. L., Unterman, R., Bopp, L. H., Brennan, M. J., Haberl, M. L. & Johnson, C. (1986). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51, 761–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cudney, R., Patel, S. & McPherson, A. (1994). Acta Cryst. D50, 479–483. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ducruix, A. & Giegé, R. (1999). Crystallization of Nucleic Acids and Proteins: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press.

- Erickson, B. D. & Mondello, F. J. (1993). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 3858–3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, K. (2000). J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 46, 283–296. [DOI] [PubMed]

- García-Ruiz, J. M., Novella, M. L., Moreno, R. & Gavira, J. A. (2001). J. Cryst. Growth, 232, 165–172.

- Gavira, J. A. & García-Ruiz, J. M. (2002). Acta Cryst. D58, 1653–1656. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Gil, L., Kumar, P., Barriault, D., Bolin, J. T., Sylvestre, M. & Eltis, L. D. (2007). J. Bacteriol. 189, 5705–5715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Haddock, J. D., Horton, J. R. & Gibson, D. T. (1995). J. Bacteriol. 177, 20–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hurtubise, Y., Barriault, D. & Sylvestre, M. (1996). J. Biol. Chem. 271, 8152–8156. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McPherson, A. (1999). Crystallization of Biological Macromolecules, p. 586. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Miroux, B. & Walker, J. E. (1996). J. Mol. Biol. 260, 289–298. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, M., Chalavi, V., Novakova-Sura, M., Laliberté, J. F. & Sylvestre, M. (2007). Biotechnol. Bioeng. 97, 496–505. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, M. & Sylvestre, M. (2005). Chem. Biol. 12, 835–846. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Mondello, F. J., Turcich, M. P., Lobos, J. H. & Erickson, B. D. (1997). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 3096–3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Provost, K. & Robert, M. C. (1991). J. Cryst. Growth, 110, 258–264.

- Robert, M. C. & Lefaucheux, F. (1988). J. Cryst. Growth, 90, 358–367.

- Seeger, M., Timmis, K. N. & Hofer, B. (1995a). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 2654–2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Seeger, M., Timmis, K. N. & Hofer, B. (1995b). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 133, 259–264. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vaillancourt, F. H., Han, S., Fortin, P. D., Bolin, J. T. & Eltis, L. D. (1998). J. Biol. Chem. 273, 34887–34895. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhu, D.-W., Lorber, B., Sauter, C., Ng, J. D., Bénas, P., Le Grimellec, C. & Giegé, R. (2001). Acta Cryst. D57, 552–558. [DOI] [PubMed]