Abstract

The role of the potent proinflammatory cytokine IL-1 in disease could clinically be investigated with the development of the IL-1 blocking agent anakinra (Kineret®), a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist. It was first tested in patients with sepsis without much benefit but was later FDA approved for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. More recently IL-1 blocking therapies are used successfully to treat a new group of immune-mediated inflammatory conditions, autoinflammatory diseases. These conditions include rare hereditary fever syndromes and pediatric and adult conditions of Still’s disease. Recently the FDA approved two additional longer acting IL-1 blocking agents, for the treatment of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS), an IL-1 dependent autoinflammatory syndrome. The study of autoinflammatory diseases revealed mechanisms of IL-1 mediated organ damage and provided concepts to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of more common diseases such as gout and Type 2 diabetes which show initial promising results with IL-1 blocking therapy.

History and Background

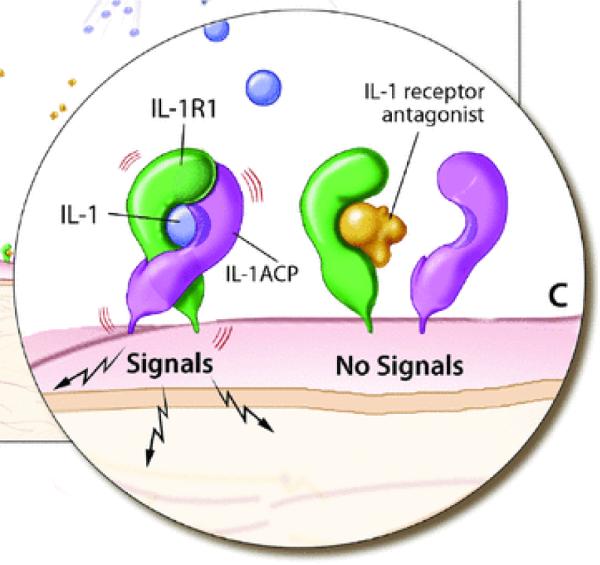

Interleukin1 (IL-1) is the prototype of a pro-inflammatory “alarm” cytokine that coordinates responses to endogenous and exogenous danger to the organism; it particularly coordinates the immune and hematologic responses. IL-1 was the first member of the family of IL-1 receptor molecules which currently consists of 11 members. IL-1α and IL-1β, both bind the biologically active IL-1 receptor (IL-1R) Type I and the inactive receptor Type II. To form an active signaling complex, the IL-1R Type I bound to either IL-1β or α, must associate with the accessory protein (IL-1RAcP) (Fig. 1). In 1986 a soluble factor was isolated from the urine of female patients that blocked the binding of IL-1 to its receptor.1 Four years later this factor, the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), was purified and cloned as the first naturally occurring receptor antagonist that blocked the action of a cytokine.2 IL-1Ra is also a member of the IL-1 family and has 26 to 30% homology with the gene structure of IL-1β and 19% with that of IL-1α. Similar to the gene location of IL-1α und β, the gene location of IL1RN is also on the human chromosome 2q14.3 As demonstrated in (Fig. 1), IL-1Ra inhibits the formation of an IL-1 signaling complex and is an important negative regulator. The balance between IL-1 and IL-1Ra is strictly regulated at many levels, and an imbalance of IL-1 and IL-1Ra has been implicated as the cause or a severity factory in a number of diseases.4 The discovery of two different autoinflammatory diseases that are mediated by two distinct genetic abnormalities in the IL-1 pathway has demonstrated the phenotypic manifestations of a dysregulated IL-1 pathway in human disease.

Figure 1.

IL-1 receptor signaling. IL-1α and IL-1β can bind to the IL-1R1 receptor which recruits the accessory receptor. This receptor complex forms a signaling unit (ACP). However binding of the IL-1 receptor antagonist to the IL-1R1 receptor inhibits IL-1 binding and does not allow for association with the ACP and therefore no signaling through the receptor occurs.

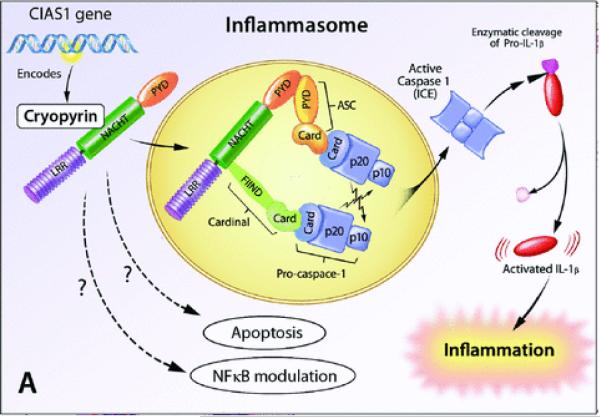

The majority of IL-1α is bound to the plasma membrane on monocytes and B cells or remains inside the cell and may serve as an autocrine growth factor and as a DNA-binding transcription factor while IL-1β is produced primarily by macrophages upon stimulation with microbial and nonmicrobial factors. Both cytokines lack a leader sequence. The events necessary to lead to the secretion of IL-1α and IL-1β are still incompletely understood. IL-1β is activated via an “inflammasome complex,” a molecular cytoplasmic platform that activates pro-caspase-1, the enzyme that cleaves pro- IL-1β in to its active form.5 IL-1α and IL-1β differ in their patterns of organ distribution. IL-1α is expressed in high levels (higher than IL-1β) in lymphoreticular organs, intestine, spleen liver and lungs; it is dominantly detected in the lumen facing epithelial cells, while IL-1β is expressed in higher levels than IL-1α in privileged organs, such as kidney, heart, skeletal muscle and brain.6 IL-1β gets rapidly activated and may coordinate a more restricted inflammatory response, it leads to induction of IL-1β itself, TNF-α, MMPs, iNOS, COX-2 and PLA 2, depending on the target cell type. IL-1β is the most powerful endogenous pyrogen known and has been implicated in tissue damage and systemic symptoms of sepsis and several inflammatory diseases.4 Therefore IL-1 has been an early target in the therapy of a number of diseases but its path through the recent medical history has been marked by failures and successes.

Clinical Studies with the IL-1 Receptor Antagonist

Sepsis

Early studies in the late 1980s suggested that IL-1 levels were elevated in patients with sepsis and levels correlated with mortality. Blockade of IL-1β has attenuated the severity of disease and mortality in experimental models of shock and sepsis.7 Although blockade of IL-1 was effective in animal models, two major studies in sepsis have provided conflicting results concerning the morbidity and mortality in humans. A phase II study in patients with sepsis suggested that treatment with the recombinant IL-1 RA, anakinra, reduced 28-day all cause- mortality in a dose-dependent manner, however a phase III trial failed to demonstrate a reduction in the 28-day mortality (Table 1). Despite the negative effect on overall mortality, subset analysis suggests that patients in shock or with gram negative sepsis are likely to most benefit from treatment. These results await further clarification and confirmation.

Table 1.

“Selected” Clinical Studies in Sepsis and Rheumatoid Arthritis

| Reference | Number of patients | Treatment intervention | Outcome | Safety | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sepsis Trials | |||||

| Fisher et al. 21 |

n= 99 recruited by 12

US centers |

open label, PLB or 100 mg loading and 72 h infusion of: IL-1ra 17, 67 or 133 mg/h |

Evaluation of mortality at day 28: PLB: (44%); 17 mg/hr (32%); 67 mg/hr (25%); 133 mg/hr (16%) |

well tolerated |

benefit in patients with high IL-6 baseline levels |

| Fisher et al. 22 | n= 893 | RCT, PLB or ANAK 100 mg loading and 72 hr infusion of: IL-1ra (1.0 or 2.0 mg/kg/h) |

Evaluation of mortality at day 28: No significant difference between PLB and treatment arms |

well tolerated |

survival benefit in retrospective analysis of patients with one or more organ dysfunction |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis Trials |

|||||

| Bresnihan et al.23; Jiang et al.24 |

n = 472 | RCT, PLB or ANAK at (30, 75 or 150 mg/day) |

Evaluation of ACR 20 at 24 wks: 27% vs. 33%, 34%, 43% |

well tolerated |

local injection site reactions are common |

| Cohen et al. 25 | n = 419 | RCT, MTX + PLB or MTX + ANAK (0.04, 0.1, 0.4, 1 or 2 mg/kg/day) |

Evaluation of ACR 20 at 12 wks: 23% vs. 19%, 30%, 36%, 42%, 35% |

well tolerated |

local injection site reactions are common |

| Cohen et al. 26 | n = 501 | RCT, MTX + PLB or MTX + ANAK (100 mg/day) |

ACR 20: 22% vs. 38%; ACR 50: 8% vs. 17%; ACR 70: 2% vs. 6% |

well tolerated |

local injection site reactions are common |

|

Fleischmann et al.27,28 |

n = 1399 | Phase IV, DMARD + PLB or DMARD + ANAK (100 mg/day) |

well tolerated |

local injection site reactions are common |

PLB = placebo; RCT = randomized controlled trial; ANAK = anakinra; ACR = American College of Rheumatology criteria of disease improvement in rheumatoid arthritis; MTX = methotrexate; DMARD = Disease modifying antirheumatic drug.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a chronic autoimmune disease is characterized by chronic inflammation of the joint lining (synovial membrane) which causes pain and swelling of multiple joints, primarily of the small joints of hands, feet and wrists. Over time, uncontrolled disease results in progressive joint damage, disability and increased mortality. Patients can be effectively treated with disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) including methotrexate and leflunomide. The evolving understanding of the immune mechanisms that perpetuate the inflammatory response has led to the development of effective targeted therapies that have revolutionized the treatment of patients with active RA. Approved biologics for the treatment of RA include TNF-α blockade, elimination of B cells and blocking of co-stimulatory pathways.8 IL-1 blockade has also been evaluated in the treatment of RA and the clinical trials are summarized in Table 1. Treatment with anakinra is well tolerated, opportunistic infections are rare compared to those seen with anti-TNF agents, and injection site reactions are the most common side effects. Treatment with anakinra is more effective than placebo, and addition of anakinra to methotrexate therapy in patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate alone, significantly improved joint swelling, pain and inflammatory blood markers as measured by ACR 20, ACR 50, and ACR 70 responses. However the inconvenience of daily injections of anakinra and the superior clinical effect of other anticytokine therapies have made anakinra a less favored choice in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.9 The clinical data of IL-1 blockade with anakinra in RA have raised the questions whether anakinra is not a “good enough drug” to block IL-1 in RA or whether targeting IL-1 in RA is the wrong cytokine.

Autoinflammatory Diseases

Monogenic Autoinflammatory Diseases

The discovery of the genetic causes of a rare group of diseases that were initially termed hereditary fever syndromes, led to the definition of a new group of diseases which are now called “autoinflammatory diseases.” Autoinflammatory diseases are a new group of immune dysregulatory disorders that are distinct from infections, allergic diseases, immunodeficiencies, and autoimmune diseases and are characterized clinically by recurrent episodes of systemic inflammation (elevation of acute phase reactants), predominance of neutrophils in the inflammatory infiltrate, and by organ-specific inflammation that can affect the skin, joints, bones, eyes, gastrointestinal tract, inner ears, and the central nervous system. Infection, autoantibodies and antigen-specific T cells are not identified in patients. Single gene mutations in a subset of the “monogenic” autoinflammatory disorders have been identified in familial Mediterranean fever, PAPA (pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne) syndrome and the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS), pediatric granulomatous arthritis (PGA), and others. The identification of these genes has helped to pinpoint dysregulated inflammatory pathways in the innate immune system and have linked the pathogenesis of these disorders to exaggerated responses to endogenous or exogenous “danger” triggers.10 The currently identified autoinflammatory diseases with known genetic causes are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

“Monogenic” Autoinflammatory Syndromes

| Disease | Clinical description/Year mutation published | Gene | Protein | Inheritance pattern | Disease onset | Flare/fever pattern | Specific organ inflammation | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMF (MIM 249100) |

1945/1997 | MEFV (16p13) | pyrin | autosomal recessive |

80% of the cases occur before the age of 20 |

1–3 days | skin, joints, peritoneum, pleura |

colchicine, rarely IL-1 and TNF blockade or thalidomide if colchicine resistant |

| TRAPS (MIM 191190) |

1982/1999 | TNFRSF1A (12p13) |

TNF receptor | autosomal dominant |

median age at onset 3 yrs |

1–4 wk | skin, eyes, joints, peritoneum, pleura |

TNF blockade, steroids, IL- 1 blockade, colchicine is ineffective |

| CAPS | ||||||||

| FCAS (MIM 120100) |

1940/2001 | CIAS1 (1q44) | Cryopyrin | autosomal dominant |

first 6 months of life, cold induced |

<24 h | skin, eyes, joints |

IL-1 blockade |

| MWS (MIM 191900) |

1961/2001 | CIAS1 (1q44) | Cryopyrin | autosomal recessive |

Infancy to adolescence |

24–48 h | skin, eyes, joints, inner ears, meninges (mild) |

IL-1 blockade |

| NOMID (MIM 607115) |

1975/2002 | CIAS1 (1q44 | Cryopyrin | autosomal dominant/de novo |

neonatal or early infancy |

continuou s with flares |

skin, eyes, joints, inner ears, meninges, bony epiphyseal hyperplasia |

IL-1 blockade |

| HIDS (MIM 260920) |

1984/1999 and 2000* |

MVK (12q24) | Mevalonate 1 kinase |

autosomal recessive |

median age at onset 6 months |

3–7 days | skin, eyes, joints, prominent lymph nodes |

NSAIDS, corticosteroi ds, TNF and IL-1 blockade |

| PGA (MIM 186580) |

1985/2001 and 2005** |

NOD2 (16q12) | Nod2 | autosomal dominant/de novo |

early childhood |

uncommo n |

skin, eyes, joints |

NSAIDS, Corticosteroi ds, methotrexat e, cyclosporine, TNF or IL- 1blockade |

| PAPA (MIM 604416) |

1997/2002 | CD2BP1 (15q24) | PSTPIP1 | autosomal dominant |

early childhood |

common | skin, joints | Local and systemic corticosteroi ds, TNF or IL- 1 blockade |

| Majeed’s syndrome (MIM 609628) |

1989/2005 | LPIN2 (18p11) | Lipin2 | autosomal recessive |

early infancy (1–19 months) |

weeks- months |

bones, periosteum, anemia |

NSAIDS, corticosteroi ds,IFNα |

| Cherubism (MIM 118400) |

1965/2001 | SH3BP2 (4p16) | SH3BP2 | autosomal dominant |

childhood, spontaneous remission by 3rd decade |

uncommo n |

jaws, eyes (rare) |

NSAIDS, TNF inhibition, interferon-α, azithromycin , bisphosphon ates |

| FCAS2 (MIM 611762) |

2008/2008 | NLRP12 (19q13) | NLRP12 (NALP12) |

autosomal dominant |

childhood, cold induced |

2–10 day, 1–3× per mo |

skin, hearing, joints, Aphtous ulcers |

corticosteroi ds, IL-1 blockade not tested |

| DIRA (MIM 612852) |

1985/2009 | IL1RN (2q14) | IL-1 receptor antagonist |

autosomal recessive |

neonatal or early infancy |

continuou s with flares |

skin, bones, lungs (rare), vasculitis (rare) |

Anakinra |

FMF—familial Mediterranean fever; TRAPS—tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic syndrome; CAPS—cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes; FCAS—familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome; MWS—Muckle-Wells syndrome; NOMID—neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease; HIDS—hyperimmunoglobulin D syndrome; PGA—pediatric granulomatous arthritis encompasses the familial Blau syndrome (MIM 186580) and the sporadic early onset sarcoidosis (MIM 609464); PAPA—pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne syndrome; DIRA-deficiency of the IL-1-receptor-antagonist, caused by autosomal-recessive “loss of function” mutations of IL1RN; MIM—Mendelian inheritance in man number.

Two groups identified the gene in 1999 and 2000.

The gene for the familial disease, Blau syndrome, was identified in 2001 and for the sporadic form, sporadic early onset sarcoidosis in 2005.

CAPS and DIRA

Two disorders that are caused by dysregulated IL-1 responses with remarkable clinical responses to IL-1 blockade will be discussed in detail in this paper, these include the spectrum of cryopyrin associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) that is caused by mutations in NLRP3, NALP311,13 and deficiency of the IL-1 receptor antagonist (DIRA) that is caused by homozygous mutations in the IL-1 receptor antagonist gene (IL1RN).14,15NLRP3 (also NALP3) encodes a protein, cryopyrin, that is a major component of the NLRP3 (NALP3 or cryopyrin) inflammasome, a macromolecular complex that activates caspase-1 the enzyme that controls activation and secretion of bioactive IL-1β (Fig. 2). The inflammasome can be triggered by a number of exogenous stimuli or “danger signals” that include conserved microbial components and large inorganic crystalline structures such as asbestos and silica, but also endogenous “danger signals” that get released for example when cells are stressed or are dying and include uric acid.

Figure 2.

The Inflammasome, an IL-1 activating platform. Cryopyrin (NLRP3, NALP3, CIAS1) is a key molecule in regulating an inflammatory cytokine processing platform. Cryopyrin, ASC, Cardinal and two procaspase-1 molecules assemble to form, the cryopyrin inflammasome that activates caspase-1. Active caspase-1, enzymatically cleaves inactive IL-1β into its active form.

Laboratory research and clinical investigations conducted in parallel revealed the pivotal role of IL-1β in causing the clinical disease phenotype of CAPS. Historically CAPS is described as three diseases, familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS), Muckle Wells syndrome (MWS), and neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID) also called chronic inflammatory neurologic, cutaneous and arthritis syndrome (CINCA). The discovery that genetic mutations in exon 3 of the gene, NLRP3 or NALP3 cause all three disease phenotypes have revealed that these syndromes are caused by IL-1β overproduction and form a disease spectrum with FCAS being the mildest and NOMID the most severe disease manifestation. The disease is autosomal dominantly inherited and a history of other affected family members can be obtained from most patients with FCAS and MWS whereas NOMID/CINCA is caused by sporadic mutations and no family history of CAPS is present.

All CAPS patients present with episodes of fever, urticarial rash, joint pain, and elevations in acute phase reactants but differ in the spectrum of multiorgan disease manifestations and in long-term morbidity and mortality. In FCAS the inflammatory episodes are triggered by cold, can present outside of the neonatal period and flares last for 12–24 h long-term outcome is favorable and amyloidosis is rare. In MWS and NOMID/CINCA, episodes of fever, urticarial rash, and arthritis are continuous and not provoked by cold and disease is usually present at or around birth.

Conjunctivitis, episcleritis, anterior ureitis and optic disc edema are also seen; and in a European cohort, amyloidosis was reported in up to 25% of patients with MWS. In MWS progressive neurosensory hearing loss presents in the 2nd to 3rd decade. In NOMID up to 60% of patients present with abnormal bony overgrowth and all patients have significant CNS inflammation. Physical disability in patients with NOMID is caused by joint contractures and severe growth retardation. Cognitive impairment is secondary to perinatal complications and central nervous system (CNS) inflammation, which includes chronic aseptic meningitis, the development of ventriculomegaly, cerebral atrophy, and seizures. Sensorineural hearing loss develops in most patients in the first decade of life, and progressive vision loss can be a consequence of optic nerve atrophy caused by chronically increased intracranial pressures. Other findings include short stature, frontal bossing, and rarely, flattening of the nasal bridge. If untreated, the reported mortality is estimated to be around 20% before patients reach adulthood.16

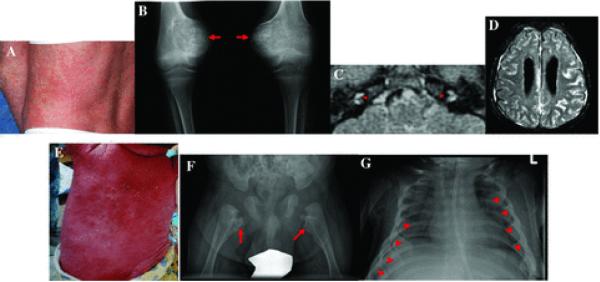

We recently found that homozygous mutations of IL1RN, the gene encoding the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), cause a severe inflammatory disease with some similarity to NOMID which has a high mortality in childhood. Mutations in IL1RN lead to complete absence of IL-1Ra and thus unopposed action of IL-1 on the IL-1 receptor and presents with systemic inflammation, skin pustulosis and mulitfocal osteomyelitis. Vasculitis and pulmonary manifestations can occur. Patients with DIRA do not have CNS or inner ear inflammation and respond dramatically to treatment with anakinra which is the very protein these children are missing. The IL1RN mutations are present in founder populations in Newfoundland, the Netherlands, and Puerto Rico and possibly Lebanon,14,15 and further founder mutations have since been identified in two other populations (personal communications). Heterozygous carriers are asymptomatic and have no detectable cytokine abnormalities in vitro. Interestingly DIRA expands the spectrum of organs that can be damaged by increased IL-1 signaling to bone inflammation and pustular skin lesions (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Clinical manifestations of NOMID/CINCA and DIRA. (A) to (D) depict characteristic clinical manifestations of patients with NOMID; (E) to (G) depict characteristic clinical manifestations of DIRA. (A) NOMID presents with an urticaria like rash, however the cellular infiltrate is neutrophilic consistent with neutrophilic dermatitis. (B) Radiographic findings of the knee show tumor like hyperostotic lesions originating in the growth plate. Once ossification is completed, the bone of these lesions is histologically normal. (C) Postcontrast FLAIR MRI of the inner ears shows abnormal cochlear enhancement suggestive of cochlear inflammation. (D) Postcontrast FLAIR MRI of brain show leptomeningeal enhancement. (E) Shows generalized pustulosis seen in a 3-month-old infant. (F) A hip X-ray shows heterotrophic ossification or periosteal cloaking of the proximal femoral metaphysic and periosteal elevation of the diaphysis. (G) Typical radiographic manifestations on a chest X-ray include widening of multiple anterior ribs (arrows).

Clinical Response to Treatment with IL-1 Blocking Agents in NOMID and DIRA

The clinical results to IL-1 blockade are striking; patients with CAPS respond well to treatment with anakinra and more recently the newer long acting IL-1 inhibitors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Selected Clinical Studies in some Autoinflammatory Diseases SyndromeStudy

| Syndrome | Study |

|---|---|

| Monogenic Disorders* | |

| Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF) | 29–31 |

| TNF receptor associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) | 32–34 |

| Hyper IgD syndrome (HIDS | 35,36 |

| CAPS (FCAS) | 37 |

| CAPS (Muckle Wells Syndrome) | 18–20 |

| CAPS (NOMID/CINCA) | 17 |

| Pediatric granulomatous arthritis (PCA)§ | 38 |

| PAPA syndrome¶ | 39 |

| Polygenic disorders** | |

| SOJIA*** | 40–45 |

| AOSD**** | 46–48 |

| Gout | 49,50 |

| Behcet’s disease | 51 |

| Diabetes Type II52 |

II52 |

1. Monogenic disorders are caused by a homozygous or heterozygous mutations in genes associated with the modulating innate immune pathways.

2. Pediatric granulomatous arthritis (PGA) is the term applied to the syndromes formerly described as Blau syndrome, a familial form of granulomatous disease, and early onset sarcoidosis, a sporadic form.

3. Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acne (PAPA) syndrome.

4. These likely polygenetic diseases do not have any genetic mutations or polymorphisms identified yet but are believed to be caused by genetic predispositions.

5. Only studies with more than 10 patients are listed; systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis (SOJIA).

6. Only studies with more than 5 patients are listed; adult onset still's disease (AOSD).

Clinical studies have shown significant improvement in the clinical symptoms of CAPS, including rash, headaches, fevers, and joint pain and marked improvement in inflammatory markers with remission in many patients, remission is also seen in 60% of patients with NOMID. IL-1 blockade with anakinra in NOMID can reverse organ inflammation imaged on MRI including CNS leptomeningitis and cochlear inflammation which is the cause for progressive hearing loss.17 Preliminary data in very young children suggest that disability may be prevented if therapy can be initiated early in life which requires early diagnosis (our own unpublished data). The dose of anakinra needed to suppress inflammation in CAPS depends on disease severity and clinical phenotype and is lowest in FCAS (0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg/day in most patients) up to 3.5 to 6 mg/kg/day in patients with NOMID/CINCA. Despite multiple open label studies showing the remarkable benefit of anakinra in CAPS, this drug has not been FDA approved for the treatment of these conditions. However recent successful drug development programs with the long acting IL-1 inhibitor Rilonacept, Arcalyst®, led to the first FDA approved therapy for CAPS.18,19 A second long acting IL-1 inhibitor, canakinumab, Ilaris®, also showed efficacy in CAPS and was recently approved by the FDA for the treatment of CAPS.20 Both agents were evaluated in patients with FCAS and MWS.

IL-1 Blockade in Other Autoinflammatory Diseases

Anakinra has also been used to prevent attacks and reduce systemic inflammation in patients with colchicine resistant FMF, HIDS, and TRAPS, and clinical responses were also reported in patients with Blau and also PAPA syndrome.

In addition to the effect in monogenic diseases, a number of presumed polygenic autoinflammatory diseases have also successfully been treated with IL-1 inhibition (Table 3). Some likely polygenic autoinflammatory diseases that share clinical similarities with some monogenic autoinflammatory diseases show impressive responses to IL-1 blockade. These include acute and chronic gout, pseudogout and the management of Schnitzler syndrome, a rare acquired urticarial disease with clinical similarities to MWS that is also associated with a monoclonal IgM gammopathy. A subset of patients with pediatric and adult Morbus Still’s disease is also responsive to IL-1 blockade. A case report of a patient with Behcet’s disease and the improvement in glucose tolerance in Type II diabetes treated with IL-1 blockade suggest that IL-1 mediated organ damage is not only limited to a small subset of rare diseases (Table 3).

Safety of IL-1 Therapy

The three currently approved drugs targeting IL-1 are listed in Table 4. All drugs are generally well tolerated. In two studies up to 71% of patients treated with anakinra developed an injection site reaction, which was typically reported within the first 4 weeks of therapy. The development of injection site reactions was uncommon after the first month of therapy. The incidence of infection was 40% in the anakinra-treated patients and 35% in placebo-treated patients. The incidence of serious infections in studies was 1.8% in anakinra-treated patients and 0.6% in placebo-treated patients over six months. These infections consisted primarily of bacterial events such as cellulitis, pneumonia, and bone and joint infections, rather than unusual, opportunistic, fungal, or viral infections. Most patients continued on study drug after the infection resolved. There were no on-study deaths due to serious infectious episodes in either study. In patients who received both anakinra and etanercept for up to 24 weeks, the incidence of serious infections was 7%. The most common infections consisted of bacterial pneumonia (4 cases) and cellulitis (4 cases). One patient with pulmonary fibrosis and pneumonia died because of respiratory failure.53

Table 4.

Currently Approved IL-1 Inhibitors BiologicClassConstructHalf-lifeOnset of actionBinding targetDose/Administration

| Biologic | Class | Construct | Half-life | Onset of action | Binding target | Dose/Administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anakinra* | IL-1 receptor antagonist |

receptor antagonistre combinant human IL-1 receptor antagonist |

4–6 h | 1–3 months in RA, within days in CAPS (pts with FCAS, MWS, NOMID/CINCA) |

IL-1 receptor Type 1 |

100 mg sc daily not approved for use in children, used in children with CAPS: 1–5 mg/kg/day/sc |

| Rilonacept** | soluble IL-1 receptor- Ig |

recombinant human IL-1 receptor –Ig fusion protein |

34–57 h | within days in CAPS (pts with FCAS and MWS) |

IL-1α, IL-1β | loading dose of 320 mg then 160 mg sc weekly pediatric dose (for children older than 12 years): 4.4 mg/kg loading dose then 2.2 mg/kg/sc weekly |

| Canakinumab*** | anti IL-1β antibody |

humanized anti IL-1β antibody |

26 days | within days in CAPS (pts with FCAS and MWS) |

IL-1β | 150 mg sc every 8wks pediatric dose (for children older than 4 years): 2 mg/kg/sc every 8 wks |

1. Anakinra (Kineret®) was approved by the U.S. FDA for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in 2001.

2. Rilonacept (Arcalyst®) was approved by the U.S. FDA for the treatment of the orphan diseases CAPS in February 2008.

3. Canakinumab (Ilaris®) was approved by the U.S. FDA for the treatment of the orphan diseases CAPS in July 2009.

The most commonly reported adverse reaction associated with Rilonacept was an injection site reaction. In 360 patients treated with Rilonacept and 179 treated with placebo, the incidence of infections was 34% versus 27% for rilonacept and placebo. One Mycobacterium intracellulare infection after bursal injection and a death from Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis occurred.54 In the canakinumab studies injection site reactions occurred in up to 9% of patients and up to 14% of patients developed vertigo with the injections.55

Summary

The discovery of the genetic causes for a number of monogenic autoinflammatory diseases in general and the discovery of mutations in NLRP3/NALP3/CIAS1 that cause CAPS and mutations in IL1RN that cause DIRA in particular, have resulted in profound advances in our understanding of the role of IL-1 in human diseases. In CAPS the genetic defects lead to the oversecretion of IL-1β and in DIRA the absence of IL-1 receptor antagonist leads to unopposed signaling of IL-1α and IL-1β through the IL-1 receptor. Through clinical studies with IL-1 blocking agents, the pivotal role of IL-1 in causing not only the systemic inflammation but also the organ specific disease has linked the discovery of the genetic cause, the understanding of the immunopathogenesis with the choice of a rational treatment approach. Following the disappointment of anti IL-1 therapy in sepsis and rheumatoid arthritis, the successes of anti-IL 1 therapy in the treatment of monogenic autoinflammatory diseases have not only clearly demonstrated the prominent role of IL-1 in human diseases, but also illustrate the success of molecular biology in exploring human diseases, and in developing a medical practice guided by our understanding of the disease pathogenesis and the rational use of targeted therapies. The expansion of the role of IL-1 in genetically complex diseases is justified by recent studies showing benefit of using IL-1 blockade in gout and Type II diabetes. Better equipped with the availability of novel long-acting biologics that block the IL-1 pathway, and the development of small orally administered molecules that target the IL-1 pathway and the inflammasome, the exploration of the IL-1 pathway in a broad spectrum of human diseases can continue.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- • 1.Balavoine JF, De Rochemonteix B, Williamson K, et al. Prostaglandin E2 and collagenase production by fibroblasts and synovial cells is regulated by urine-derived human interleukin 1 and inhibitor(s) J. Clin. Invest. 1986;78:1120–1124. doi: 10.1172/JCI112669. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 192 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=J.%20Clin.%20Invest.&rft.atitle=Prostaglandin%20E2%20and%20collagenase%20production%20by%20fibroblasts%20and%20synovial%20cells%20is%20regulated%20by%20urine%E2%80%90derived%20human%20interleukin%201%20and%20inhibitor%28s%29&rft.volume=78&rft.spage=1120&rft.epage=1124&rft.date=1986&rft.aulast=Balavoine&rft.aufirst=J.F.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 2.Hannum CH, Wilcox CJ, Arend WP, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist activity of a human interleukin-1 inhibitor. Nature. 1990;343:336–340. doi: 10.1038/343336a0. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 960 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Nature&rft.atitle=Interleukin%E2%80%901receptorantagonistactivityofahumaninterleukin%E2%80%901inhibitor&rft.volume=343&rft.spage=336&rft.epage=340&rft.date=1990&rft.aulast=Hannum&rft.aufirst=C.H.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 3.Dinarello CA. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 2172 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Blood&rft.atitle=Biologicbasisforinterleukin%E2%80%901indisease&rft.volume=87&rft.spage=2095&rft.epage=2147&rft.date=1996&rft.aulast=Dinarello&rft.aufirst=C.A.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 4.Arend WP. The balance between IL-1 and IL-1Ra in disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:323–340. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00020-5. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 182 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=CytokineGrowthFactorRev.&rft.atitle=ThebalancebetweenIL%E2%80%901andIL%E2%80%901Raindisease&rft.volume=13&rft.spage=323&rft.epage=340&rft.date=2002&rft.aulast=Arend&rft.aufirst=W.P.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 5.Petrilli V, Dostert C, Muruve DA, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a danger sensing complex triggering innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007;19:615–622. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.09.002. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 137 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Curr.Opin.Immunol.&rft.atitle=Theinflammasome%3Aadangersensingcomplextriggeringinnateimmunity&rft.volume=19&rft.spage=615&rft.epage=622&rft.date=2007&rft.aulast=Petrilli&rft.aufirst=V.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 6.Hacham M, Argov S, White RM, et al. Distinct patterns of IL-1 alpha and IL-1 beta organ distribution–a possible basis for organ mechanisms of innate immunity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2000;479:185–202. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46831-x_16. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 12 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Adv.%20Exp.%20Med.%20Biol.&rft.atitle=Distinct%20patterns%20of%20IL%E2%80%901%20alpha%20and%20IL%E2%80%901%20beta%20organ%20distribution%E2%80%93a%20possible%20basis%20for%20organ%20mechanisms%20of%20innate%20immunity&rft.volume=479&rft.spage=185&rft.epage=202&rft.date=2000&rft.aulast=Hacham&rft.aufirst=M.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 7.Cain BS, Meldrum DR, Harken AH, Mcintyre RC., Jr. The physiologic basis for anticytokine clinical trials in the treatment of sepsis. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 1998;186:337–350. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00036-2. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 41 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=J.Am.Coll.Surg.&rft.atitle=Thephysiologicbasisforanticytokineclinicaltrialsinthetreatmentofsepsis&rft.volume=186&rft.spage=337&rft.epage=350&rft.date=1998&rft.aulast=Cain&rft.aufirst=B.S.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 8.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Koeller M, et al. New therapies for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2007;370:1861–1874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60784-3. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 82 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Lancet&rft.atitle=Newtherapiesfortreatmentofrheumatoidarthritis&rft.volume=370&rft.spage=1861&rft.epage=1874&rft.date=2007&rft.aulast=Smolen&rft.aufirst=J.S.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 9.O’Dell JR. Therapeutic strategies for rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2591–2602. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040226. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 158 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=N.Engl.J.Med.&rft.atitle=Therapeuticstrategiesforrheumatoidarthritis&rft.volume=350&rft.spage=2591&rft.epage=2602&rft.date=2004&rft.aulast=O%E2%80%99Dell&rft.aufirst=J.R.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 10.Glaser RL, Goldbach-Mansky R. The spectrum of monogenic autoinflammatory syndromes: understanding disease mechanisms and use of targeted therapies. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008;8:288–298. doi: 10.1007/s11882-008-0047-1. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 4 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Curr.AllergyAsthmaRep.&rft.atitle=Thespectrumofmonogenicautoinflammatorysyndromes%3Aunderstandingdiseasemechanismsanduseoftargetedtherapies&rft.volume=8&rft.spage=288&rft.epage=298&rft.date=2008&rft.aulast=Glaser&rft.aufirst=R.L.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 11.Hoffman HM, Mueller JL, Broide DH, et al. Mutation of a new gene encoding a putative pyrin-like protein causes familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2001;29:301–305. doi: 10.1038/ng756. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 349 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Nat.Genet.&rft.atitle=Mutationofanewgeneencodingaputativepyrin%E2%80%90likeproteincausesfamilialcoldautoinflammatorysyndromeandMuckle%E2%80%90Wellssyndrome&rft.volume=29&rft.spage=301&rft.epage=305&rft.date=2001&rft.aulast=Hoffman&rft.aufirst=H.M.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlin. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 12.Aksentijevich I, Nowak M, Mallah M, et al. De novo CIAS1 mutations, cytokine activation, and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in patients with neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID): a new member of the expanding family of pyrin-associated autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:3340–3348. doi: 10.1002/art.10688. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ Full Article (HTML) ○ PDF(350K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRheum.&rft.atitle=DenovoCIAS1mutations%2Ccytokineactivation%2Candevidenceforgeneticheterogeneityinpatientswithneonatal%E2%80%90onsetmultisysteminflammatorydisease%28NOMID%29%3Aanewmemberoftheexpandingfamilyofpyrin%E2%80%90associatedautoinflamm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 13.Feldmann J, Prieur AM, Quartier P, et al. Chronic infantile neurological cutaneous and articular syndrome is caused by mutations in CIAS1, a gene highly expressed in polymorphonuclear cells and chondrocytes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;71:198–203. doi: 10.1086/341357. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 213 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Am.J.Hum.Genet.&rft.atitle=ChronicinfantileneurologicalcutaneousandarticularsyndromeiscausedbymutationsinCIAS1%2Cagenehighlyexpressedinpolymorphonuclearcellsandchondrocytes&rft.volume=71&rft.spage=198&rft.epage=203&rft.date=2002&rft.aulast=Feldmann&rft.aufirst=J.&rfr. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 14.Aksentijevich I, Masters SL, Ferguson PJ, et al. An autoinflammatory disease with deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2426–2437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807865. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 16 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=N.Engl.J.Med.&rft.atitle=Anautoinflammatorydiseasewithdeficiencyoftheinterleukin%E2%80%901%E2%80%90receptorantagonist&rft.volume=360&rft.spage=2426&rft.epage=2437&rft.date=2009&rft.aulast=Aksentijevich&rft.aufirst=I.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 15.Reddy S, Jia S, Geoffrey R, et al. An autoinflammatory disease due to homozygous deletion of the IL1RN locus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2438–2444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809568. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 11 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=N.Engl.J.Med.&rft.atitle=AnautoinflammatorydiseaseduetohomozygousdeletionoftheIL1RNlocus&rft.volume=360&rft.spage=2438&rft.epage=2444&rft.date=2009&rft.aulast=Reddy&rft.aufirst=S.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 16.Prieur AM, Griscelli C, Lampert F, et al. A chronic, infantile, neurological, cutaneous and articular (CINCA) syndrome. A specific entity analysed in 30 patients. Scand. J. Rheumatol. Suppl. 1987;66:57–68. doi: 10.3109/03009748709102523. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Scand.J.Rheumatol.Suppl.&rft.atitle=Achronic%2Cinfantile%2Cneurological%2Ccutaneousandarticular%28CINCA%29syndrome.Aspecificentityanalysedin30patients&rft.volume=66&rft.spage=57&rft.epage=68&rft.date=1987&rft.aulast=Prieur&rft.aufirst=A.M.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 17.Goldbach-Mansky R, Dailey NJ, Canna SW, et al. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1beta inhibition. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:581–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055137. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 139 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=N.Engl.J.Med.&rft.atitle=Neonatal%E2%80%90onsetmultisysteminflammatorydiseaseresponsivetointerleukin%E2%80%901betainhibition&rft.volume=355&rft.spage=581&rft.epage=592&rft.date=2006&rft.aulast=Goldbach%E2%80%90Mansky&rft.aufirst=R.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 18.Goldbach-Mansky R, Shroff SD, Wilson M, et al. A pilot study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the long-acting interleukin-1 inhibitor rilonacept (interleukin-1 Trap) in patients with familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2432–2442. doi: 10.1002/art.23620. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ Full Article (HTML) ○ PDF(398K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRheum.&rft.atitle=Apilotstudytoevaluatethesafetyandefficacyofthelong%E2%80%90actinginterleukin%E2%80%901inhibitorrilonacept%28interleukin%E2%80%901Trap%29inpatientswithfamilialcoldautoinflammatorysyndrome&rft.volume=58&rft.spage=2432&rft.epage=2442&rft.date= [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 19.Hoffman HM, Throne ML, Amar NJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of rilonacept (interleukin-1 Trap) in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes: results from two sequential placebo-controlled studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2443–2452. doi: 10.1002/art.23687. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ Full Article (HTML) ○ PDF(370K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRheum.&rft.atitle=Efficacyandsafetyofrilonacept%28interleukin%E2%80%901Trap%29inpatientswithcryopyrin%E2%80%90associatedperiodicsyndromes%3Aresultsfromtwosequentialplacebo%E2%80%90controlledstudies&rft.volume=58&rft.spage=2443&rft.epage=2452&rft.date=2008&rft.aulast=Hoffma. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 20.Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, et al. Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:2416–2425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810787. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 19 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=N.Engl.J.Med.&rft.atitle=Useofcanakinumabinthecryopyrin%E2%80%90associatedperiodicsyndrome&rft.volume=360&rft.spage=2416&rft.epage=2425&rft.date=2009&rft.aulast=Lachmann&rft.aufirst=H.J.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 21.Fisher CJ, Jr., Slotman GJ, Opal SM, et al. Initial evaluation of human recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of sepsis syndrome: a randomized, open-label, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Crit. Care Med. 1994;22:12–21. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199401000-00008. ○ PubMed, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 263 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Crit.CareMed.&rft.atitle=Initialevaluationofhumanrecombinantinterleukin%E2%80%901receptorantagonistinthetreatmentofsepsissyndrome%3Aarandomized%2Copen%E2%80%90label%2Cplacebo%E2%80%90controlledmulticentertrial&rft.volume=22&rft.spage=12&rft.epage=21&rft.date=1994&rft.aulast=F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 22.Fisher CJ, Jr., Dhainaut JF, Opal SM, et al. Recombinant human interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of patients with sepsis syndrome. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phase III rhIL-1ra Sepsis Syndrome Study Group. JAMA. 1994;271:1836–1843. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 550 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=JAMA&rft.atitle=Recombinanthumaninterleukin1receptorantagonistinthetreatmentofpatientswithsepsissyndrome.Resultsfromarandomized%2Cdouble%E2%80%90blind%2Cplacebo%E2%80%90controlledtrial.PhaseIIIrhIL%E2%80%901raSepsisSyndromeStudyGroup&rft.volume=271&rft.spage. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 23.Bresnihan B, Alvaro-Gracia JM, Cobby M, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:2196–2204. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199812)41:12<2196::AID-ART15>3.0.CO;2-2. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ PDF(955K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRheum.&rft.atitle=Treatmentofrheumatoidarthritiswithrecombinanthumaninterleukin%E2%80%901receptorantagonist&rft.volume=41&rft.spage=2196&rft.epage=2204&rft.date=1998&rft.aulast=Bresnihan&rft.aufirst=B.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 24.Jiang Y, Genant HK, Watt I, et al. A multicenter, double-blind, dose-ranging, randomized, placebo-controlled study of recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: radiologic progression and correlation of Genant and Larsen scores. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1001–1009. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200005)43:5<1001::AID-ANR7>3.0.CO;2-P. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ PDF(78K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRheum.&rft.atitle=Amulticenter%2Cdouble%E2%80%90blind%2Cdose%E2%80%90ranging%2Crandomized%2Cplacebo%E2%80%90controlledstudyofrecombinanthumaninterleukin%E2%80%901receptorantagonistinpatientswithrheumatoidarthritis%3AradiologicprogressionandcorrelationofGenan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 25.Cohen S, Hurd E, Cush J, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist, in combination with methotrexate: results of a twenty-four-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:614–624. doi: 10.1002/art.10141. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ Full Article (HTML) ○ PDF(149K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Arthritis%20Rheum.&rft.atitle=Treatment%20of%20rheumatoid%20arthritis%20with%20anakinra%2C%20a%20recombinant%20human%20interleukin%E2%80%901%20receptor%20antagonist%2C%20in%20combination%20with%20methotrexate%3A%20results%20of%20a%20twenty%E2%80%90four%E2%80%90week%2C%20multicenter%2C%20randomized%2C%20double%E2%80%90blind%2C%20placebo%E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 26.Cohen SB, Moreland LW, Cush JJ, et al. A multicentre, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial of anakinra (Kineret), a recombinant interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with background methotrexate. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2004;63:1062–1068. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.016014. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 81 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Ann.Rheum.Dis.&rft.atitle=Amulticentre%2Cdoubleblind%2Crandomised%2Cplacebocontrolledtrialofanakinra%28Kineret%29%2Carecombinantinterleukin1receptorantagonist%2Cinpatientswithrheumatoidarthritistreatedwithbackgroundmethotrexate&rft.volume=63&rft.spage=1062&r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 27.Fleischmann RM, Schechtman J, Bennett R, et al. Anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (r-metHuIL-1ra), in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A large, international, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:927–934. doi: 10.1002/art.10870. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ Full Article (HTML) ○ PDF(80K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRheum.&rft.atitle=Anakinra%2Carecombinanthumaninterleukin%E2%80%901receptorantagonist%28r%E2%80%90metHuIL%E2%80%901ra%29%2Cinpatientswithrheumatoidarthritis%3AAlarge%2Cinternational%2Cmulticenter%2Cplacebo%E2%80%90controlledtrial&rft.volume=48&rft.spage=927&rft.epage=934&r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 28.Fleischmann RM, Tesser J, Schiff MH, et al. Safety of extended treatment with anakinra in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2006;65:1006–1012. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.048371. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 41 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Ann.Rheum.Dis.&rft.atitle=Safetyofextendedtreatmentwithanakinrainpatientswithrheumatoidarthritis&rft.volume=65&rft.spage=1006&rft.epage=1012&rft.date=2006&rft.aulast=Fleischmann&rft.aufirst=R.M.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 29.Gattringer R, Lagler H, Gattringer KB, et al. Anakinra in two adolescent female patients suffering from colchicine-resistant familial Mediterranean fever: effective but risky. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;37:912–914. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01868.x. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ Full Article (HTML) ○ PDF(107K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Eur.J.Clin.Invest.&rft.atitle=Anakinraintwoadolescentfemalepatientssufferingfromcolchicine%E2%80%90resistantfamilialMediterraneanfever%3Aeffectivebutrisky&rft.volume=37&rft.spage=912&rft.epage=914&rft.date=2007&rft.aulast=Gattringer&rft.aufirst=R.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 30.Kuijk LM, Govers AM, Frenkel J, Hofhuis WJ. Effective treatment of a colchicine-resistant familial Mediterranean fever patient with anakinra. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007;66:1545–1546. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.071498. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 10 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Ann.Rheum.Dis.&rft.atitle=Effectivetreatmentofacolchicine%E2%80%90resistantfamilialMediterraneanfeverpatientwithanakinra&rft.volume=66&rft.spage=1545&rft.epage=1546&rft.date=2007&rft.aulast=Kuijk&rft.aufirst=L.M.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 31.Roldan R, Ruiz AM, Miranda MD, Collantes E. Anakinra: new therapeutic approach in children with Familial Mediterranean Fever resistant to colchicine. Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:504–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.04.001. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 10 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=JointBoneSpine&rft.atitle=Anakinra%3AnewtherapeuticapproachinchildrenwithFamilialMediterraneanFeverresistanttocolchicine&rft.volume=75&rft.spage=504&rft.epage=505&rft.date=2008&rft.aulast=Roldan&rft.aufirst=R.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 32.Simon A, Bodar EJ, Van Der Hilst JC, et al. Beneficial response to interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in traps. Am. J. Med. 2004;117:208–210. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.039. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 48 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Am.J.Med.&rft.atitle=Beneficialresponsetointerleukin1receptorantagonistintraps&rft.volume=117&rft.spage=208&rft.epage=210&rft.date=2004&rft.aulast=Simon&rft.aufirst=A.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 33.Gattorno M, Pelagatti MA, Meini A, et al. Persistent efficacy of anakinra in patients with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1516–1520. doi: 10.1002/art.23475. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ Full Article (HTML) ○ PDF(62K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRheum.&rft.atitle=Persistentefficacyofanakinrainpatientswithtumornecrosisfactorreceptor%E2%80%90associatedperiodicsyndrome&rft.volume=58&rft.spage=1516&rft.epage=1520&rft.date=2008&rft.aulast=Gattorno&rft.aufirst=M.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 34.Sacre K, Brihaye B, Lidove O, et al. Dramatic improvement following interleukin 1beta blockade in tumor necrosis factor receptor-1-associated syndrome (TRAPS) resistant to anti-TNF-alpha therapy. J. Rheumatol. 2008;35:357–358. ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 6 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=J.Rheumatol.&rft.atitle=Dramaticimprovementfollowinginterleukin1betablockadeintumornecrosisfactorreceptor%E2%80%901%E2%80%90associatedsyndrome%28TRAPS%29resistanttoanti%E2%80%90TNF%E2%80%90alphatherapy&rft.volume=35&rft.spage=357&rft.epage=358&rft.date=2008&rft.aulast=Sacre&rft.aufirst=K. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 35.Bodar EJ, Van Der Hilst JC, Drenth JP, et al. Effect of etanercept and anakinra on inflammatory attacks in the hyper-IgD syndrome: introducing a vaccination provocation model. Neth. J. Med. 2005;63:260–264. ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 46 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Neth.J.Med.&rft.atitle=Effectofetanerceptandanakinraoninflammatoryattacksinthehyper%E2%80%90IgDsyndrome%3Aintroducingavaccinationprovocationmodel&rft.volume=63&rft.spage=260&rft.epage=264&rft.date=2005&rft.aulast=Bodar&rft.aufirst=E.J.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 36.Cailliez M, Garaix F, Rousset-Rouviere C, et al. Anakinra is safe and effective in controlling hyperimmunoglobulinaemia D syndrome-associated febrile crisis. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2006;29:763. doi: 10.1007/s10545-006-0408-7. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 21 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=J.Inherit.Metab.Dis.&rft.atitle=AnakinraissafeandeffectiveincontrollinghyperimmunoglobulinaemiaDsyndrome%E2%80%90associatedfebrilecrisis&rft.volume=29&rft.spage=763&rft.date=2006&rft.aulast=Cailliez&rft.aufirst=M.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 37.Hoffman HM, Rosengren S, Boyle DL, et al. Prevention of cold-associated acute inflammation in familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome by interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Lancet. 2004;364:1779–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17401-1. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 161 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Lancet&rft.atitle=Preventionofcold%E2%80%90associatedacuteinflammationinfamilialcoldautoinflammatorysyndromebyinterleukin%E2%80%901receptorantagonist&rft.volume=364&rft.spage=1779&rft.epage=1785&rft.date=2004&rft.aulast=Hoffman&rft.aufirst=H.M.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 38.Arostegui JI, Arnal C, Merino R, et al. NOD2 gene-associated pediatric granulomatous arthritis: clinical diversity, novel and recurrent mutations, and evidence of clinical improvement with interleukin-1 blockade in a Spanish cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3805–3813. doi: 10.1002/art.22966. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ Full Article (HTML) ○ PDF(267K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRheum.&rft.atitle=NOD2gene%E2%80%90associatedpediatricgranulomatousarthritis%3Aclinicaldiversity%2Cnovelandrecurrentmutations%2Candevidenceofclinicalimprovementwithinterleukin%E2%80%901blockadeinaSpanishcohort&rft.volume=56&rft.spage=3805&rft.epage=3813&rft.dat. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 39.Dierselhuis MP, Frenkel J, Wulffraat NM, Boelens JJ. Anakinra for flares of pyogenic arthritis in PAPA syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:406–408. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh479. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 38 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Rheumatology%28Oxford%29&rft.atitle=AnakinraforflaresofpyogenicarthritisinPAPAsyndrome&rft.volume=44&rft.spage=406&rft.epage=408&rft.date=2005&rft.aulast=Dierselhuis&rft.aufirst=M.P.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 40.Reiff A. The use of anakinra in juvenile arthritis. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2005;7:434–440. doi: 10.1007/s11926-005-0047-2. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Curr.Rheumatol.Rep.&rft.atitle=Theuseofanakinrainjuvenilearthritis&rft.volume=7&rft.spage=434&rft.epage=440&rft.date=2005&rft.aulast=Reiff&rft.aufirst=A.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 41.Pascual V, Allantaz F, Arce E, et al. Role of interleukin-1 (IL-1) in the pathogenesis of systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and clinical response to IL-1 blockade. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1479–1486. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050473. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 142 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=J.%20Exp.%20Med.&rft.atitle=Role%20of%20interleukin%E2%80%901%20%28IL%E2%80%901%29%20in%20the%20pathogenesis%20of%20systemic%20onset%20juvenile%20idiopathic%20arthritis%20and%20clinical%20response%20to%20IL%E2%80%901%20blockade&rft.volume=201&rft.spage=1479&rft.epage=1486&rft.date=2005&rft.aulast=Pascual&rft.aufirst=V.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 42.Gattorno M, Piccini A, Lasiglie D, et al. The pattern of response to anti-interleukin-1 treatment distinguishes two subsets of patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:1505–1515. doi: 10.1002/art.23437. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ Full Article (HTML) ○ PDF(263K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRheum.&rft.atitle=Thepatternofresponsetoanti%E2%80%90interleukin%E2%80%901treatmentdistinguishestwosubsetsofpatientswithsystemic%E2%80%90onsetjuvenileidiopathicarthritis&rft.volume=58&rft.spage=1505&rft.epage=1515&rft.date=2008&rft.aulast=Gattorno&rft.aufirst=M.&rfr_id=info%3Asi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 43.Lequerre T, Quartier P, Rosellini D, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) treatment in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis or adult onset Still disease: preliminary experience in France. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008;67:302–308. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076034. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 41 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Ann.Rheum.Dis.&rft.atitle=Interleukin%E2%80%901receptorantagonist%28anakinra%29treatmentinpatientswithsystemic%E2%80%90onsetjuvenileidiopathicarthritisoradultonsetStilldisease%3ApreliminaryexperienceinFrance&rft.volume=67&rft.spage=302&rft.epage=308&rft.date=2008&rft.aulas. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 44.Quartier P. Still’s disease (Systemic-Onset Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis) Arch. Pediatr. 2008;15:865–866. doi: 10.1016/S0929-693X(08)71944-4. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 1 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Arch.Pediatr.&rft.atitle=%5BStill%27sdisease%28Systemic%E2%80%90OnsetJuvenileIdiopathicArthritis%29%5D&rft.volume=15&rft.spage=865&rft.epage=866&rft.date=2008&rft.aulast=Quartier&rft.aufirst=P.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 45.Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Goodman S, et al. Adalimumab with or without methotrexate in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359:810–820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706290. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 23 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=N.Engl.J.Med.&rft.atitle=Adalimumabwithorwithoutmethotrexateinjuvenilerheumatoidarthritis&rft.volume=359&rft.spage=810&rft.epage=820&rft.date=2008&rft.aulast=Lovell&rft.aufirst=D.J.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 46.Lequerre T, Quartier P, Rosellini D, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) treatment in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis or adult onset Still disease: preliminary experience in France. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008;67:302–308. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.076034. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 41 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Ann.Rheum.Dis.&rft.atitle=Interleukin%E2%80%901receptorantagonist%28anakinra%29treatmentinpatientswithsystemic%E2%80%90onsetjuvenileidiopathicarthritisoradultonsetStilldisease%3ApreliminaryexperienceinFrance&rft.volume=67&rft.spage=302&rft.epage=308&rft.date=2008&rft.aulas. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 47.Fitzgerald AA, Leclercq SA, Yan A, et al. Rapid responses to anakinra in patients with refractory adult-onset Still’s disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1794–1803. doi: 10.1002/art.21061. Direct Link: ○ Abstract ○ Full Article (HTML) ○ PDF(116K) ○ References http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRheum.&rft.atitle=Rapidresponsestoanakinrainpatientswithrefractoryadult%E2%80%90onsetStill%27sdisease&rft.volume=52&rft.spage=1794&rft.epage=1803&rft.date=2005&rft.aulast=Fitzgerald&rft.aufirst=A.A.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 48.Godinho F.M. Vasques, Santos M.J. Parreira, Canas DS. Refractory adult onset Still’s disease successfully treated with anakinra. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2005;64:647–648. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.026617. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 27 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Ann.Rheum.Dis.&rft.atitle=RefractoryadultonsetStill%27sdiseasesuccessfullytreatedwithanakinra&rft.volume=64&rft.spage=647&rft.epage=648&rft.date=2005&rft.aulast=VasquesGodinho&rft.aufirst=F.M.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 49.So A, De Smedt T, Revaz S, Tschopp J. A pilot study of IL-1 inhibition by anakinra in acute gout. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2007;9:R28. doi: 10.1186/ar2143. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 88 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=ArthritisRes.Ther.&rft.atitle=ApilotstudyofIL%E2%80%901inhibitionbyanakinrainacutegout&rft.volume=9&rft.spage=R28&rft.date=2007&rft.aulast=So&rft.aufirst=A.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 50.McGonagle D, Tan AL, Shankaranarayana S, et al. Management of treatment resistant inflammation of acute on chronic tophaceous gout with anakinra. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2007;66:1683–1684. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.073759. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 22 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Ann.Rheum.Dis.&rft.atitle=Managementoftreatmentresistantinflammationofacuteonchronictophaceousgoutwithanakinra&rft.volume=66&rft.spage=1683&rft.epage=1684&rft.date=2007&rft.aulast=McGonagle&rft.aufirst=D.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 51.Botsios C, Sfriso P, Furlan A, et al. Resistant Behcet disease responsive to anakinra. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008;149:284–286. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-4-200808190-00018. ○ PubMed, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 7 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=Ann.Intern.Med.&rft.atitle=ResistantBehcetdiseaseresponsivetoanakinra&rft.volume=149&rft.spage=284&rft.epage=286&rft.date=2008&rft.aulast=Botsios&rft.aufirst=C.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 52.Larsen CM, Faulenbach M, Vaag A, et al. Interleukin-1-receptor antagonist in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356:1517–1526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065213. ○ CrossRef, ○ PubMed, ○ ChemPort, ○ Web of Science® Times Cited: 146 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05159.x/full?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=info%3Aofi%2Ffmt%3Akev%3Amtx%3Ajournal&rft.genre=article&rft.jtitle=N.Engl.J.Med.&rft.atitle=Interleukin%E2%80%901%E2%80%90receptorantagonistintype2diabetesmellitus&rft.volume=356&rft.spage=1517&rft.epage=1526&rft.date=2007&rft.aulast=Larsen&rft.aufirst=C.M.&rfr_id=info%3Asid%2Fwiley.com%3AOnlineLibrary. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • 53.Anakinra package insert. http://www.kineretrx.com/professional/pi.jsp.

- • 54.Rilonacept package insert. http://www.regeneron.com/ARCALYST-fpi.pdf.

- • 55.Canakinumab package insert. http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/products/name/ilaris.jsp.