Abstract

Objective

To assess whether obese or moderately-severely obese adults have impaired quadriceps strength and muscle quality in comparison with non-obese adults age 50–59 years with and without knee osteoarthritis (OA)

Design

Cross-sectional observational study

Setting

Rural community acquired sample

Subjects

77 Men and 84 women age 50–59 years

Methods

Comparisons using mixed models for clustered data (2 lower limbs per participant) between groups defined by BMI (<30kg/m2, 30–35kg/m2, and ≥35kg/m2) with and without knee OA

Main Outcome Measurement

the slope of the relationship between quadriceps muscle cross sectional area (ssCT) and isokinetic knee extensor strength (dynamometer) in each BMI and OA group.

Results

There were 113 (48.7% female), 101 (38.6% female), and 89 (73.0% female) limbs in the <30 kg/m2, 30–35 kg/m2, and ≥35kg/m2 BMI groups respectively. Knee OA was present in 10.6%, 28.7%, and 58.4% of the limbs in each of these respective groups. Quadriceps cross sectional area (CSA) did not significantly differ between BMI groups in either sex or between subjects with and without knee OA. Peak quadriceps strength also did not significantly differ by BMI group, or by the presence of knee OA. Multivariable analyses also demonstrated that peak quadriceps strength did not differ by BMI group, even after adjusting for a) sex, b) OA status, c) intramuscular fat, or d) quadriceps attenuation. The slopes for the relationships between quadriceps strength and CSA did not differ by BMI group, OA status or their interaction.

Conclusions

Obese individuals at risk for knee OA do not appear to have altered muscle strength or muscle quality compared with non-obese adults aged 50–59 years. The absence of a difference in the relationship between peak quadriceps strength and CSA provided further evidence that there was not an impairment in quadriceps muscle quality in this cohort, suggesting that factors other than strength might mediate the association between obesity and knee OA.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a well-established risk factor for knee osteoarthritis (OA).[1] The mechanism for this relationship has not been established, but in addition to biochemical factors, biomechanical factors likely contribute to this increased risk. Since the quadriceps muscles play an important role in stabilizing the knee during loading, and strength can protect against incident [2] and progressive [3] symptomatic knee OA, relative quadriceps weakness in relation to the excess body weight may play a role in the increased risk for knee OA associated with obesity.[4] While obese adults generally have greater absolute quadriceps strength than non-obese adults,[5–8] this increase may not be in proportion to nor sufficient to offset the loading effects of greater body weight. Several studies have found that obesity is associated with decreased quadriceps strength per body mass[4, 9–12] and per total lean body mass (LBM).[8, 13] In addition, there is some evidence that obese adults with knee OA have reduced quadriceps strength per unit of lower limb lean body mass (L-LBM) assessed by DXA,[7, 14, 15] suggesting that impaired muscle function (lower strength per unit of muscle mass) in obese adults may also contribute to the development of knee OA. However, estimates of LBM by DXA can be falsely high with increasing fat mass, thus leading to error in these measurements.[16]

To better understand whether quadriceps weakness could explain the increased risk for knee OA with obesity, it is first necessary to examine whether relative weakness is present– an impairment in the relationship between muscle strength and bulk. On a person-specific basis, one can examine specific strength (strength per unit muscle bulk), but on a population basis, it is important to examine whether there is a systematic difference in the relationship between quadriceps strength and bulk (slope) in obese adults in comparison with non-obese adults. As would be predicted from their increased body mass, examination of subjects with and without knee OA demonstrates that obese subjects have increased absolute L-LBM as measured by DXA.[17] However, some of this is non-contractile as DXA cannot distinguish between muscle and the lean component of adipose tissue.[16, 18, 19] In contrast, CT can provide an accurate assessment of muscle bulk.

Normally, mid-thigh muscle mass is approximately 2.5 times that of fat mass,[20] but obese individuals have increased intra-muscular (fat within muscle cells) and inter-muscular fat (fat between muscle cells).[21, 22] Skeletal muscle fibers in the vastus lateralis of obese subjects contain roughly twice as much triglyceride as in lean subjects.[22] Such differences may affect muscle function. Attenuation is the degree to which a signal is reduced by passing through tissue and can be used as an indirect measure of tissue density. Attenuation of lean mass and fat mass can be quantified by CT scan, providing information about the composition of skeletal muscle and the distribution of fat within the muscle.[23, 24] Decreased attenuation is due to increased fat in muscle and may correlate with weakness not explained by DXA measurement of L-LBM.[25]

Assessing the relationship between muscle strength and cross-sectional area (CSA), represented as the slope of strength per scaled unit of muscle CSA, may enable quantification of relative quadriceps weakness by eliminating non-contractile tissue from the denominator. If obese adults have a significantly different relationship between strength and CSA than non-obese individuals, it would suggest an impairment of quadriceps muscle function. In contrast, if there were not a significant difference in the relationship, it would suggest that factors other than muscle quality may be more important in mediating the association between obesity and knee OA.[26]

We studied whether there are differences in the relationships between quadriceps strength and CSA, comparing non-obese and obese adults with and without knee OA to determine whether the slope of the relationship between quadriceps strength and CSA, scaled for body size, is impaired with obesity. In order to compare results with prior research that assessed specific strength as well as advance understanding of research findings that did not scale for body size, we assessed these outcomes as well.

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

Subjects

One hundred and sixty-four subjects were recruited. Subjects were recruited primarily from the clinical centers of the Multicenter Osteoarthritis (MOST) Study,[2] a longitudinal study of 3,026 men and women aged 50–79 (N=151), and also from sending letters to patients who had ICD-9 codes characteristic of knee OA and who had knee radiographs in the past year (N=13). All subjects provided written, informed consent for the study that was approved by the investigators’ Institutional Review Boards.

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) was determined through the examination of radiographs completed as part of the MOST study protocol or in the clinic. Weight-bearing, fixed flexion posteroanterior[27] views of the knees were obtained at baseline and scored by two independent readers as previously described.[28] All knees were graded using the Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) scale.[29] Knee osteoarthritis was defined as at least one definite osteophyte visible at standard image size on posteroanterior knee radiographs (KL grade ≥2).[30]

Eligibility Criteria

Subjects were age 50 to 59 years and had no history of neuromuscular disease, acute illness, wasting illness, renal insufficiency requiring hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, systemic inflammatory arthropathy, Paget’s disease, villonodular synovitis, ochonosis, Charcot knee joint, neuropathic arthropathy, acromegaly, hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, osteochondromatosis, gout, recurrent pseudogout, or osteopetrosis. Subjects’ lower limbs were excluded if they had a history of a knee injury that required use of a brace or gait aid for greater than 2 days, total knee arthroplasty, knee surgery within the previous 6 months, a periarticular fracture, or a lower limb joint infection.

Measures

Knee OA Symptoms

The modified Western Ontario McMasters Knee Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada) was used as a descriptive measure to characterize knee pain, stiffness, and physical difficulty (17 function, 5 pain, and 2 stiffness items). In addition, subjects were asked “During the past 30 days, have you had any pain, aching, or stiffness in your knee on most days?”

Physical Activity

The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE, New England Research Institute, Inc., Watertown, MA) was used to characterize physical activity level (10 items).

Isokinetic Strength Testing

Isokinetic Strength Testing of the quadriceps was performed on a Cybex 350 dynamometer (Cybex International, Inc., Medway, Massachusetts). Isokinetic quadriceps strength was evaluated at 60 degrees per second in each lower limb, following a standardized protocol.[31] No subjects had a history of cerebral aneurysm, back surgery within the previous 3-months, myocardial infarction or cataract surgery within the previous 6-week period, or an untreated inguinal hernia. Limbs were not tested if there had been an injury that met exclusion criteria.

Anthropometric Measurements

Standing height and weight were measured from which body mass index (BMI) was calculated as kg/m2 as described previously.[32] Subjects were recruited in the following body composition groups: <30 kg/m2, 30–35 kg/m2 and ≥35 kg/m2.

Single-Slice CT (ssCT) of the Midthigh

Using a 16–detector Siemens Somation Sensation, a scout image was completed to determine the mid-thigh site, located half the distance from the anterior superior iliac spine to the superior border of the patella. A 500ms, 5mm, single slice image was collected at 120kVp and 100mA. Images for each lower limb were systematically examined for Hounsfield units characteristic of muscle and the cross sectional area of the muscle (0 to 100 HU), and intramuscular and extramuscular fat (−190 to −30 HU) as well as the mean Hounsfield units per cross-sectional area (attenuation) were measured using SliceOMatic software (Version 4.2, Tomovision: Montreal, Canada).[25] Average test-retest correlation (ICC) for the ssCT measurements was 0.987 (range: .981–.999). Subjects weighing over 450 lbs did not undergo CT scans due to equipment weight limitations.

Statistical Analyses

In planning the study, a power calculation was conducted based on the regression of quadriceps strength and CSA. A total of 107 subjects would be sufficient to detect, at the 0.05 significance level with 0.90 power, an incremental increase in R2 of at least 5% due to weight group from a reduced model with an R2 of 45% (i.e. adding BMI group as a predictor of strength to a model that already includes OA status, sex, and muscle bulk). In order to have a distribution of subjects sufficient to conduct subgroup analyses within strata of sex and OA status, a total of 164 subjects were enrolled. With this larger sample size, the power to detect the 5% incremental increase in R2 was increased to 0.96.

Since our main goal was to assess differences in the slope of the association between quadriceps strength and CSA among the obesity groups, a confirmatory power calculation following completion of the study was conducted based on the regression of quadriceps strength and CSA (slope of the regression line). With a regression residual error standard deviation of 30 and quad CSA standard deviation presented in Table 2, the distribution of subjects recruited was sufficient to detect at the 0.05 significance level a difference in slope of strength/CSA of at least 1.3 N•m/cm2 between the obesity groups with 0.80 power.[33.]

Table 2.

Number of Limbs in Each Strata

| <30 kg/m2 | 30–35 kg/m2 | ≥35kg/m2 | All Limbs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No OA | Men | 50 | 42 | 11 | 103 |

| Women | 51 | 30 | 26 | 107 | |

| + OA | Men | 8 | 20 | 13 | 41 |

| Women | 4 | 9 | 39 | 52 | |

| Total Limbs | 113 | 101 | 89 | 303 | |

Data analysis was performed using SAS software (Version 9.1, Cary, NC). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for intergroup comparisons at the subject level (e.g. age, weight, BMI) to assess for differences in the composition of the BMI and OA strata that might account for differences in the relationship between quadriceps strength and bulk if any were found. Tukey’s method was used for pairwise comparisons. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between continuous variables of primary interest (strength and CSA) to assess for degree of covariance prior to entry into multivariable models. For all limb-based analyses (e.g. strength, CSA), PROC MIXED was used to control for correlation between limbs from the same subject when assessing relationships between quadriceps strength and CSA for (a) non-obese versus obese (BMI of 30–35 kg/m2) vs. moderately-severely obese (BMI ≥35 kg/m2) subjects as well as (b) secondary analyses comparing those with and without radiographic knee OA. In addition to descriptive statistics and plots, mixed linear models were used to address our null hypothesis that (a) obesity or (b) knee OA does not modify the relationship between quadriceps strength and CSA. This was done for the primary outcome variable, the slope of the relationship in each group as well as for the secondary and tertiary variables of interest, specific strength and adipose distribution. Bivariate analyses were stratified by sex and in multivariate models, sex was entered as an independent variable, and interaction terms with sex were also included to determine whether the relationship differed by sex. Subsequent models also adjusted for activity level (PASE) and amount of intramuscular fat, to determine whether the relationship between strength and bulk persisted independent of these variables.

Linear regression was used to estimate the average allometric scaling parameter in each group using the log-transformed allometric modeling equation ln(strength) = ®0 + ®1 ln(lean mass).[8, 26, 34–36] In this equation ®1 represented the allometric scaling parameter. The estimated allometric scaling parameter was used to calculate the normalized strength independent of body size for each subject in each subgroup. Scatter plots were used to assess the relationship between the resulting normalized strength values and CSA. This body size-independent measure of strength was used for those models described above in which allometrically scaled strength was the dependent outcome measure.

RESULTS

Subjects

For the 164 subjects enrolled, 303 limbs were available for analysis after excluding 25 for the following reasons: injury or recent surgery (9), knee pain limiting ability to complete strength testing (8), weight exceeded capacity of the CT table (2), CT data acquisition problems (6). Additional missing data that affected some, but not all analyses, occurred for strength testing due to limbs meeting exclusion criteria for the test (21 limbs). Therefore, complete data were available for limbs in 161 subjects.

In the BMI <30 kg/m2, 30–35 kg/m2, and ≥35kg/m2 groups, the study included 113 (48.7% female), 101 (38.6% female), and 89 (73.0% female) limbs respectively for whom complete datasets were available. Knee OA was present in 10.6%, 28.7%, and 58.4% of the limbs in each of these respective BMI groups. Descriptive statistics for subject/limb characteristics are summarized in Table 1 and the distribution of those with and without knee OA are summarized in Table 2. These reflect the number of limbs used in analyses.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics Comparing BMI Groups*

| Characteristic | Non-Obese <30 kg/m2 | Obese 30–35 kg/m2 | Mod-Severe Obese ≥35kg/m2 | All | p-value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.0±2.8 | 54.7±2.8 | 55.2±2.5 | 55.0±2.7 | .9248 |

| % women | 48.7% | 38.6% | 73.0% | 52.5% | <.0001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) {range} | 24.2±2.3 {20.2–29.9} | 32.8±1.2 {30.4–34.9} | 40.7±6.4 {35.0–63.8} | 31.9±7.7 | Differ by Definition |

| Weight (kg) | 71.7±11.5 | 97.2±10.4 | 110.3±17.2 | 90.5±20.6 | <.0001 |

| PASE Score | 213.1±96.2 | 218.3±70.6 | 183.1±82.4 | 206.7±85.4 | .0145 |

| Radiographic OA (%) | 10.6% | 28.7% | 58.4% | 30.7% | <.0001 |

| KL Grade | |||||

| 0 | 65 | 33 | 21 | 119 | <.0001 |

| 1 | 36 | 39 | 16 | 91 | |

| 2 | 6 | 12 | 21 | 39 | |

| 3 | 6 | 12 | 25 | 43 | |

| 4 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 11 | |

Mean±SD and Freqencies

Comparing BMI Groups

Quadriceps Bulk

Quadriceps cross sectional area (CSA) significantly differed between men and women (66.3±11.2 cm2 vs. 45.2±6.7 cm2; p<.0001). However, quadriceps CSA did not significantly differ between BMI groups in either sex (Table 3) nor between those with and without knee OA (66.3±11.6 cm2 vs. 66.3±11.1 cm2 for men, 45.1±7.4 cm2 vs. 45.3±6.4 cm2 for women). In addition, there was no significant OA group*Weight group interaction effect on quadriceps CSA, meaning that the difference in mean quadriceps CSA due to OA did not significantly differ among the weight groups, and likewise, the differences in the mean due to BMI was independent of OA (p=0.7224).

Table 3.

Quadriceps Strength and Bulk by BMI group

| Quadriceps Parameter | Sex | Non-Obese <30 kg/m2 | Obese 30–35 kg/m2 | Mod-Severe ≥35kg/m2 | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Isokinetic Quadriceps Strength (N•m) | M | 148.8±30.9 | 151.3±38.3 | 159.1±42.8 | .5297 |

| F | 85.4±24.0 | 95.6±20.9 | 86.2±27.5 | .1038 | |

| Quadriceps CSA (cm2) | M | 65.8±10.7 | 67.0±12.2 | 66.0±9.6 | .8500 |

| F | 45.0±5.7 | 44.7±7.1 | 45.8±7.3 | .6865 | |

| Specific Strength (N•m/cm2) | M | 2.3±0.5 | 2.3±0.5 | 2.5±0.7 | .1751 |

| F | 1.9±0.5 | 2.2±0.5 | 1.9±0.6 | .0269 | |

| Intramuscular Quadriceps Fat (cm2) | M | 9.7±5.4 | 19.4±5.5 | 29.3±9.9 | <.0001 |

| F | 12.1±6.3 | 19.5±6.9 | 24.9±7.3 | <.0001 | |

| Extramuscular Thigh Fat (cm2) | M | 59.9±17.6 | 103.6±39.9 | 151.3±44.6 | <.0001 |

| F | 120.0±32.1 | 185.3±54.8 | 222.9±62.9 | <.0001 |

p-value comparing same-sex BMI groups, unadjusted for multiple comparisons

Peak Isokinetic Quadriceps Strength

In the single-factor model, peak quadriceps strength significantly differed by sex (151.5±36.1 vs. 88.2±25.0 N•m; p<.0001), but not by BMI group (p=.5997), or by the presence of knee OA (p=.2489). Adjustment of this model for activity level (i.e. strength = {BMI group} {sex} {OA group} {PASE}) revealed that strength did differ by OA (p=.0281). Multivariable analyses also demonstrated that peak quadriceps strength did not differ by BMI group (p=0.3946), even after adjusting for a) sex (p<0.0001), b) OA status (p=0.0387), c) intramuscular fat (p=0.7101), d) quadriceps attenuation (p=0.2864), and e) activity level (p=0.3333). Repetition of all analyses using allometrically scaled quadriceps strength had equivalent results.

Quadriceps Specific Strength

Similarly, in men, specific strength (quadriceps strength per CSA) did not differ by BMI group (non-obese and obese: 2.3N•m/cm2 and moderately-severely obese: 2.5 N•m/cm2; p=0.4859) or OA group (without OA: 2.3 N•m/cm2 and with OA: 2.4 N•m/cm2; p=0.8856), either before adjustment (Table 3) or in the multiple regression model. In women, without adjustment for covariates, there were statistically significant differences in specific strength comparing BMI groups (Table 3) and subjects with (2.0±0.5N•m) and without (1.8±0.5N•m) knee OA (p=.0286) before adjustment. However, after adjusting for covariates in the multiple regression model, the effect of BMI (non-obese: 1.8 N•m/cm2, obese: 2.1N•m/cm2 and moderately-severely obese: 1.9 N•m/cm2; p=0.1556) and knee OA (without OA: 2.0 N•m/cm2 and with OA: 1.8 N•m/cm2; p=0.0857) were no longer significant.

Multivariate Analyses: The Relationship Between Quadriceps Strength and CSA

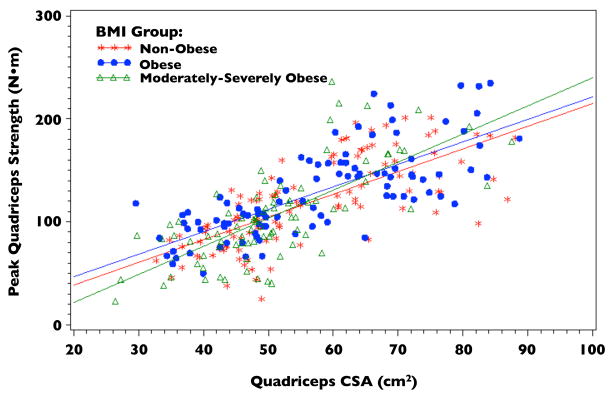

No significant differences were found when comparing the relationship between quadriceps CSA and strength between BMI groups (p=0.7512; Figure 1). Additionally, controlling for intramuscular fat did not strengthen the relationship between quadriceps strength and CSA. The following regression equations for each BMI group were derived from the fitted model for quadriceps strength with quadriceps CSA, BMI group, and their interaction as the independent variables:

Figure 1.

Quadriceps Cross-sectional Area (CSA) vs. Peak Quadriceps Strength by BMI Group

Peak Quadriceps Strength (Non-obese) = −5.33 + 2.20 * Quad CSA

Peak Quadriceps Strength (Obese) = −4.88 + 2.32 * Quad CSA

Peak Quadriceps Strength (Mod-Severe) = −23.50 + 2.52 * Quad CSA

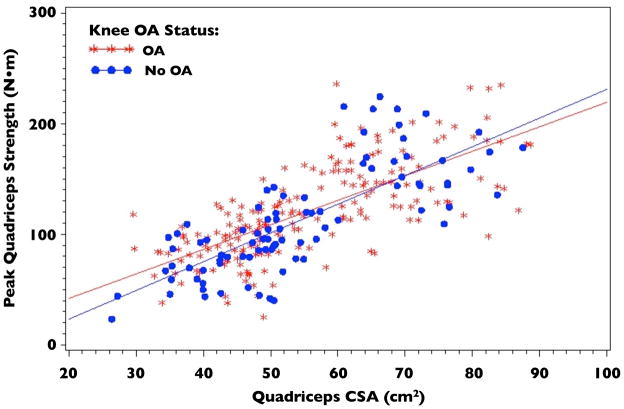

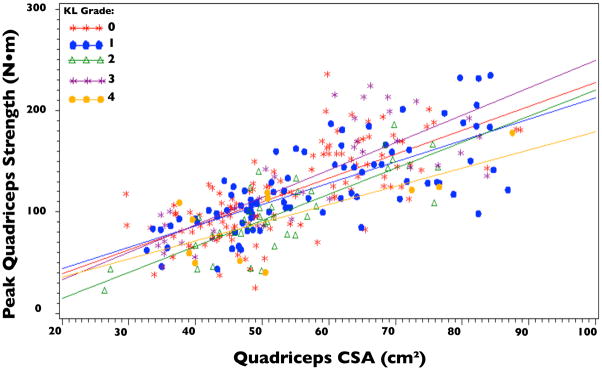

Knee OA Status did not significantly modify the relationship between quadriceps strength and CSA (p=0.1805; Figure 2). This remained true with the prospective definition of knee OA (KL grade ≥2) as well as in sensitivity analyses in which knee OA was defined as KL grade ≥ 3 and in which the outcome was defined as knee pain, aching or stiffness on most of the past 30 days. Additionally, the relationship between quadriceps strength and CSA did not differ comparing KL grades (Figure 3; p=0.7586). Regression Equations by knee OA status derived from the fitted model for quadriceps strength with quadriceps CSA, OA group, and their interaction as the independent variables were:

Figure 2.

Quadriceps Cross-sectional Area (CSA) vs. Peak Quadriceps Strength by Knee OA Status

Figure 3.

Quadriceps Cross-sectional Area (CSA) vs. Peak Quadriceps Strength by Kellgren Lawrence Grade

Peak Quadriceps Strength (No OA) = −4.59 + 2.21 * Quad CSA

Peak Quadriceps Strength (OA) = −25.81 + 2.58 * Quad CSA

Additionally, the relationship between quadriceps strength and CSA was independent of KL grades (Figure 3; p=0.7586).

Thigh Fat Distribution

Extramuscular fat CSA significantly differed by BMI group in men and women (Table 3). Intramuscular fat CSA (including subfascial and intramuscular fat) significantly differed between BMI groups in men and women (p<.0001), but not between OA groups (p=.4038). As expected, intramuscular fat also significantly correlated with BMI, body weight, and mean attenuation of the quadriceps (r= 0.69, 0.64, and −0.34 respectively: all p<.0001) (Table 4). Quadriceps attenuation significantly differed among BMI groups and were significantly associated with the amount of intramuscular fat in men and women (p<.0001), but did not differ by OA group (p=.7128). Correlations between attenuation and measures of quadriceps bulk and strength are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlation Coefficients

| Quadriceps CSA (cm2) | BMI (kg/m2) | Peak Quadriceps Strength (N•m) | Quadriceps Attenuation (HU) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quadriceps Attenuation (HU) | .23 (p<.0001) | −.34 (p<.0001) | .10 (p=.0779) | - |

| Intramuscular Fat (cm2) | −.19 (p=.0010) | .69 (p <.0001) | −.02 (p=.7301) | −.46 (p <.0001) |

| Extramuscular Fat (cm2) | −.57 (p<.0001) | .66 (p<.0001) | −.42 (p<.0001) | −.26 (p<.0001) |

DISCUSSION

In this study, there were no statistically significant differences in isokinetic quadriceps strength between non-obese, obese and moderately-severely obese adults either before or after adjusting for a) sex, b) OA status, c) intramuscular fat, d) quadriceps attenuation, or e) activity level. These results were consistent for quadriceps strength per CSA (specific strength), for strength adjusted for body size (allometric scaling), and for the slope of the relationship between quadriceps strength and bulk in men and women with and without knee OA. These results also were consistent with those of other studies that found no difference in absolute[37] or adjusted quadriceps strength by BMI group.[6]

In addition to assessing the slope of the relationship in each BMI and OA group as well as the specific strength of each group, this study also used allometric scaling to assess for relative weakness in obese older adults. Reporting relative weakness by dividing strength by body mass, a ratio method, assumes that a 150 kg person is proportionately twice as strong as a 75 kg person, resulting in obligate classification of heavier people as weak. As fat mass increases, the ratios of both strength and muscle to body mass will necessarily decrease due to an increased denominator, although much of that tissue is non-contractile. Ratio standards imply a linear relationship with an intercept of 0 and a slope of 1. However, many biological variables, although increasing with body size, do not increase in a 1:1 ratio and therefore cannot be accurately described by a ratio standard. In order to understand the true relationship between strength and body composition, allometric scaling assesses the relationship recognizing that although a positive correlation between strength and LBM is expected,[38, 39] like other biological standards, it may not be a ratio.[34, 35, 40, 41] Equations for normalizing strength have been proposed by several investigators.[42–47]

Our results contrast with those of Hulens, who found that obese have greater fat free mass and lower allometrically-scaled isokinetic knee extensor strength in comparison to normal weight subjects.[8] One potential reason for the difference in findings may relate to overestimation of fat free mass (a correlate of LBM) by bioelectrical impedance.[48] This possibility is supported by the relatively low correlation between quadriceps strength and fat free mass in that study.[8] In addition, 80% of the subjects in that study were under the age of 50, whereas all subjects in the current study were 50–59 years old, suggesting the possibility that strength may differ by BMI group in younger, but not in older adults.

This possibility is strengthened by reports from the Health ABC study, showing that in adults age 70–79, although specific strength was lower with increased total body fat mass, fat mass did not explain much of the total variance in strength or specific strength in either sex.[49] That study also reported a relationship between higher attenuation and higher specific strength.[25] Similar to that study,[25] we found that quadriceps attenuation was greater in men than women and that attenuation decreased with increasing BMI. However, our results differed from those of that study, in that we did not find a significant association between quadriceps strength and attenuation (p=.94 and .41 in men and women respectively), even after adjustment for quadriceps CSA, height, weight, and age. However, in both studies intramuscular adipose CSA (Table 4) was not associated with peak quadriceps strength.

Although the primary focus of this study was assessment of the relationship between quadriceps strength and CSA in subjects of varying BMI, another interesting finding was that neither quadriceps strength nor the relationship between quadriceps strength and CSA differed between those with and those without radiographic knee OA (KL grade ≥2). Additional sensitivity analyses of the KL≥2 definition of knee OA were completed, demonstrating that the relationship also did not differ if OA was defined at a threshold of KL grade ≥3, by trend with individual KL grades, or by the presence or absence of frequent knee symptoms. This result contrasts with those of other studies that found quadriceps weakness in adults with knee OA,[2, 4, 50–55] adults with knee pain,[56] and adults with tibiofemoral OA in the absence of pain.[4] However, it is consistent with reports that did not find a difference in quadriceps strength in those with and without knee pain,[57, 58] and the quadriceps CSA as well as the correlation between CSA and isokinetic strength were very similar to those reported by Gür for women with knee OA,[59] suggesting that muscle atrophy may not be present in women with knee OA.[58]

There are several potential explanations for the lack of a difference in quadriceps strength in our subjects with and without knee OA. Although our study group had a similar mean BMI and weight to the study of Liikavainio, that study included only men, used clinical rather than radiographic criteria for knee OA for the predictor,[60] and used isometric measures of strength and ultrasound to quantify muscle bulk, rather than isokinetic strength and single-slice CT.[55] Another possible explanation relates to the relative homogeneity of the subjects studied– nearly all were rural adults with risk factors for or presence of knee OA and all were 50–59 years of age. Prior studies that reported a difference in strength included adults in older age groups and therefore those with knee OA may have had differences in their activity levels or degree of sarcopenia with aging. This possibility is supported by the fact that after we adjusted for activity level (PASE) in the full model, quadriceps strength differed by OA group.

Another possible reason for the absence of a detectable difference in strength between OA groups could relate to misclassification of subjects by radiographs. For example, if the subjects classified as not having knee OA were indistinguishable from subjects with knee OA due to subclinical disease, they may have had early OA and quadriceps strength and CSA similar to subjects with radiographic knee OA. If this had been the case, then the past 3 years of follow-up for the parent MOST study may have resulted in a high rate of incident knee OA among subjects without knee OA during the time of this study. This did not occur, so the classification of subjects in the non-OA and OA groups was likely appropriate.

A potential source of error in the current study was the lack of correction for gravity in the MOST strength testing protocol. Someone with a heavier shank would need to resist the force of gravity on that segment through the arc of motion, introducing error into the measurement of strength. However, although there was potential for greater error in more obese subjects due to a greater leg mass, there was not a significant difference in shank mass by DXA, comparing non-obese, obese and moderately-severely obese BMI groups in our study (means 3.4, 3.6, and 3.5kg; p=.7776). Since leg mass did not differ between obesity groups, we would not expect differences in the maximal gravity-eliminated torque correction between the groups and therefore this should not have affected the overall comparison of strength between groups.

Despite this potential source of measurement error, there were no significant differences in the strength per unit CSA of the quadriceps comparing BMI or OA groups, suggesting that if error in the strength measurement had been present, it was evenly distributed among groups. The absence of a difference in the relationship between quadriceps strength and CSA was not surprising, considering that this relationship has not been found to differ by sex, by race, or by age. In this study, a correlation between quadriceps strength and CSA of r=.73 would suggest that approximately 53% of strength could be accounted for by CSA. This was similar to the findings of a prior study in which 24–61% of strength was explained by CSA.[59] Thus, our finding that the relationship between strength and bulk is preserved regardless of obesity pattern is consistent with the findings in other groups. In considering this finding, it is important to remember that cross-sectional area of muscle is assumed to be proportional to muscle mass.[61] Pennate muscles, such as the quadriceps, have a greater fiber density than fusiform muscles, resulting in a curvilinear rather than a linear relationship between strength and cross-sectional area. [62]

Our finding of no difference in quadriceps CSA in those with and without knee OA differed from a report in which adults with knee OA had 13–14% decreased quadriceps CSA.[63] In another study, those with painful knee OA did not have significantly decreased quadriceps CSA, despite lower knee extensor strength and specific torque,[25] suggesting a qualitative impairment in the muscle, such as reduced activation or altered muscle morphology, rather than a quantitative etiology such as atrophy. However, other studies have not found evidence of reduced activation of the quadriceps in people with knee OA.[53]

Returning to the central focus of this study– whether there is relative weakness with obesity that could mediate risk for knee OA– the evidence did not suggest that this is the case. First, we did not find impairment of gross quadriceps strength with higher BMI. Second, there was not a difference in specific strength comparing the BMI groups. Although there was greater intramuscular fat with greater BMI, this did not appear to have an effect on either strength or strength per CSA of the quadriceps muscle. In addition, although attenuation (reflected by the mean Houndsfield Units for the muscle), a known correlate of intracellular fat[24] was associated with BMI, it was not associated with strength. This provided further evidence that measures of obesity were not associated with quadriceps strength in this cohort. Since DXA is known to overestimate lean mass in obese subjects, leading to an underestimate of specific strength,[16, 18, 19, 49] the use of CT in this study enabled a more accurate measurement of specific strength than in prior studies that used DXA.

Other strengths of this study relate to the subjects recruited. The MOST study participants form a community-acquired cohort. Inclusion of these participants in this ancillary study allows better genralizability to other community-dwelling adults, age 50–59, than would be possible with clinic-based recruitment. In addition, as presented in Table 2, 210 did not have OA and 93 had OA. Although the prevalence of radiographic knee OA is only 2–5% in this age group,[64] we were able to recruit sufficient numbers to power these analyses due to the resources of the MOST cohort.[31] The higher representation of women and those with severe obesity within the OA group is consistent with the very strong associations of these factors with knee OA.[65] In addition to enabling recruitment of adequate numbers of representative participants, the standardized protocols for collection of data and frequent quality assurance checks for each of the measures enhanced the quality of the data utilized in this study.

Despite the lack of evidence of a difference in strength in adults age 50–59 by BMI group, it is currently unknown how much strength is required for more obese individuals to adequately control knee joint loading. Our finding of no difference in quadriceps strength or specific strength could possibly be interpreted as relative weakness if greater strength were necessary to stabilize the knee joint in the context of excess body mass. Therefore, further biomechanical studies are needed to assess the degree of strength necessary to resist the effects of increased body mass on the knee.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by NIH (5K12HD001097) through the Association of Academic Physiatrists Rehabilitation Medicine Scientist Training Program and NIH grants to The University of Iowa (James Torner, PhD - AG18832), Boston University (David Felson, MD - AG18820), University of Alabama (Cora E. Lewis, MD MSPH - AG18947), and University of California San Francisco (Michael Nevitt, PhD - AG19069).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Teichtahl AJ, Wang Y, Wluka AE, Cicuttini FM. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis: new insights provided by body composition studies. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2008;16:232–240. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segal NA, Torner JC, Felson D, et al. Effect of thigh strength on incident radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in a longitudinal cohort. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2009;61:1210–1217. doi: 10.1002/art.24541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Segal NA, Glass NA, Torner J, et al. Quadriceps weakness predicts risk for knee joint space narrowing in women in the MOST cohort. Osteoarthritis and cartilage/OARS. Osteoarthritis Research Society. 2010;18:769–775. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slemenda C, Brandt KD, Heilman DK, et al. Quadriceps weakness and osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:97–104. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-2-199707150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wearing SC, Hennig EM, Byrne NM, Steele JR, Hills AP. Musculoskeletal disorders associated with obesity: a biomechanical perspective. Obesity reviews. 2006;7:239–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rolland Y, Lauwers-Cances V, Pahor M, Fillaux J, Grandjean H, Vellas B. Muscle strength in obese elderly women: effect of recreational physical activity in a cross-sectional study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:552–557. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slemenda C, Heilman DK, Brandt KD, et al. Reduced quadriceps strength relative to body weight: a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis in women? Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1951–1959. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199811)41:11<1951::AID-ART9>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulens M, Vansant G, Lysens R, Claessens AL, Muls E, Brumagne S. Study of differences in peripheral muscle strength of lean versus obese women: an allometric approach. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:676–681. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blimkie CJ, Sale DG, Bar-Or O. Voluntary strength, evoked twitch contractile properties and motor unit activation of knee extensors in obese and non-obese adolescent males. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1990;61:313–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00357619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jadelis K, Miller ME, Ettinger WH, Jr, Messier SP. Strength, balance, and the modifying effects of obesity and knee pain: results from the Observational Arthritis Study in Seniors (oasis) J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:884–891. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyatake N, Fujii M, Nishikawa H, et al. Clinical evaluation of muscle strength in 20–79-years-old obese Japanese. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2000;48:15–21. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Toda Y, Segal N, Toda T, Kato A, Toda F. A decline in lower extremity lean body mass per body weight is characteristic of women with early phase osteoarthritis of the knee. The Journal of rheumatology. 2000;27:2449–2454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lue YJ, Chang JJ, Chen HM, Lin RF, Chen SS. Knee isokinetic strength and body fat analysis in university students. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2000;16:517–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandt KD, Heilman DK, Slemenda C, et al. A comparison of lower extremity muscle strength, obesity, and depression scores in elderly subjects with knee pain with and without radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1937–1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madsen OR, Brot C, Petersen MM, Sorensen OH. Body composition and muscle strength in women scheduled for a knee or hip replacement. A comparative study of two groups of osteoarthritic women. Clin Rheumatol. 1997;16:39–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02238761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Segal NA, Glass NA, Baker JL, Torner JC. Correcting for fat mass improves DXA quantification of quadriceps specific strength in obese adults aged 50–59 years. J Clin Densitom. 2009;12:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segal NA, Toda Y. Absolute reduction in lower limb lean body mass in Japanese women with knee osteoarthritis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2005;11:245–249. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000182148.74893.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine JA, Abboud L, Barry M, Reed JE, Sheedy PF, Jensen MD. Measuring leg muscle and fat mass in humans: comparison of CT and dual- energy X-ray absorptiometry. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:452–456. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Visser M, Fuerst T, Lang T, Salamone L, Harris TB. Validity of fan-beam dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for measuring fat-free mass and leg muscle mass. Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study--Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry and Body Composition Working Group. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md) 1999;87:1513–1520. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.4.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treuth MS, Ryan AS, Pratley RE, et al. Effects of strength training on total and regional body composition in older men.[erratum appears in J Appl Physiol 1994 Dec;77(6):followi] Journal of Applied Physiology. 1994;77:614–620. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.2.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jozsi AC, Trappe TA, Starling RD, et al. The influence of starch structure on glycogen resynthesis and subsequent cycling performance. Int J Sports Med. 1996;17:373–378. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malenfant P, Joanisse DR, Theriault R, Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE, Simoneau JA. Fat content in individual muscle fibers of lean and obese subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1316–1321. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodpaster BH, Thaete FL, Kelley DE. Composition of skeletal muscle evaluated with computed tomography. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;904:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE, Thaete FL, He J, Ross R. Skeletal muscle attenuation determined by computed tomography is associated with skeletal muscle lipid content. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:104–110. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodpaster BH, Carlson CL, Visser M, et al. Attenuation of skeletal muscle and strength in the elderly: The Health ABC Study. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2157–2165. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davies MJ, Dalsky GP. Normalizing strength for body size differences in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:713–717. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199705000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nevitt MC, Peterfy C, Guermazi A, et al. Longitudinal performance evaluation and validation of fixed-flexion radiography of the knee for detection of joint space loss. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2007;56:1512–1520. doi: 10.1002/art.22557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Segal NA, Felson DT, Torner JC, et al. Greater trochanteric pain syndrome: epidemiology and associated factors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2007;88:988–992. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kellgren JH, Lawrence JS. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502. doi: 10.1136/ard.16.4.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Felson DT, Nevitt MC. Epidemiologic studies for osteoarthritis: new versus conventional study design approaches. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2004;30:783–797. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segal NA, Torner JC, Felson DT, et al. Knee extensor strength does not protect against incident knee symptoms at 30 months in the multicenter knee osteoarthritis (MOST) cohort. PM R. 2009;1:459–465. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Segal NA, Torner JC, Yang M, Curtis JR, Felson DT, Nevitt MC. Muscle Mass Is More Strongly Related to Hip Bone Mineral Density Than Is Quadriceps Strength or Lower Activity Level in Adults Over Age 50Year. J Clin Densitom. 2008;11:503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dupont WD, Plummer WD., Jr Power and sample size calculations. A review and computer program. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11:116–128. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(90)90005-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaric S. Muscle strength testing: use of normalisation for body size. Sports Med. 2002;32:615–631. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232100-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nevill AM, Holder RL. Scaling, normalizing, and per ratio standards: an allometric modeling approach. J Appl Physiol. 1995;79:1027–1031. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.3.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weir JP, Housh TJ, Johnson GO, Housh DJ, Ebersole KT. Allometric scaling of isokinetic peak torque: the Nebraska Wrestling Study. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1999;80:240–248. doi: 10.1007/s004210050588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Apovian CM, Frey CM, Wood GC, Rogers JZ, Still CD, Jensen GL. Body mass index and physical function in older women. Obes Res. 2002;10:740–747. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maughan RJ, Watson JS, Weir J. Strength and cross-sectional area of human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1983;338:37–49. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harris T. Muscle mass and strength: relation to function in population studies. J Nutr. 1997;127:1004S–1006S. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.5.1004S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jaric S, Radosavljevic-Jaric S, Johansson H. Muscle force and muscle torque in humans require different methods when adjusting for differences in body size. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2002;87:304–307. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanner JM. Fallacy of per-weight and per-surface area standards, and their relation to spurious correlation. J Appl Physiol. 1949;2:1–15. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1949.2.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards RH, Young A, Hosking GP, Jones DA. Human skeletal muscle function: description of tests and normal values. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;52:283–290. doi: 10.1042/cs0520283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Backman E, Johansson V, Hager B, Sjoblom P, Henriksson KG. Isometric muscle strength and muscular endurance in normal persons aged between 17 and 70 years. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1995;27:109–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stoll T, Huber E, Seifert B, Michel BA, Stucki G. Maximal isometric muscle strength: normative values and gender-specific relation to age. Clinical Rheumatology. 2000;19:105–113. doi: 10.1007/s100670050026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrews AW, Thomas MW, Bohannon RW. Normative values for isometric muscle force measurements obtained with hand-held dynamometers. Physical therapy. 1996;76:248–259. doi: 10.1093/ptj/76.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gross MT, McGrain P, Demilio N, Plyler L. Relationship between multiple predictor variables and normal knee torque production. Phys Ther. 1989;69:54–62. doi: 10.1093/ptj/69.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muscular weakness assessment: use of normal isometric strength data. The National Isometric Muscle Strength (NIMS) Database Consortium. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:1251–1255. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(96)90188-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baumgartner RN, Ross R, Heymsfield SB. Does adipose tissue influence bioelectric impedance in obese men and women? Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md) 1998;84:257–262. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newman AB, Haggerty CL, Goodpaster B, et al. Strength and muscle quality in a well-functioning cohort of older adults: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:323–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baker KR, Xu L, Zhang Y, et al. Quadriceps weakness and its relationship to tibiofemoral and patellofemoral knee osteoarthritis in Chinese: the Beijing osteoarthritis study. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2004;50:1815–1821. doi: 10.1002/art.20261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fisher NM, White SC, Yack HJ, Smolinski RJ, Pendergast DR. Muscle function and gait in patients with knee osteoarthritis before and after muscle rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 1997;19:47–55. doi: 10.3109/09638289709166827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hortobagyi T, Garry J, Holbert D, Devita P. Aberrations in the control of quadriceps muscle force in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2004;51:562–569. doi: 10.1002/art.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lewek MD, Rudolph KS, Snyder-Mackler L. Quadriceps femoris muscle weakness and activation failure in patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:110–115. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(03)00154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tan J, Balci N, Sepici V, Gener FA. Isokinetic and isometric strength in osteoarthrosis of the knee. A comparative study with healthy women. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 1995;74:364–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liikavainio T, Isolehto J, Helminen HJ, et al. Loading and gait symmertry during level and stair walking in asymptomatic subjects with knee osteoarthritis: Importance of quadriceps femoris in reducing impact force during heel strike? The Knee. 2007;14:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O’Reilly SC, Jones A, Muir KR, Doherty M. Quadriceps weakness in knee osteoarthritis: the effect on pain and disability. Ann Rheum Dis. 1998;57:588–594. doi: 10.1136/ard.57.10.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McAlindon TE, Cooper C, Kirwan JR, Dieppe PA. Determinants of disability in osteoarthritis of the knee. Ann Rheum Dis. 1993;52:258–262. doi: 10.1136/ard.52.4.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Petterson SC, Barrance P, Buchanan T, Binder-Macleod S, Snyder-Mackler L. Mechanisms underlying quadriceps weakness in knee osteoarthritis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:422–427. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31815ef285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gur H, Cakin N. Muscle mass, isokinetic torque, and functional capacity in women with osteoarthritis of the knee. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1534–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peat G, Thomas E, Duncan R, Wood L, Hay E, Croft P. Clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: performance in the general population and primary care. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2006;65:1363–1367. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.051482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wickiewicz TL, Roy RR, Powell PL, Edgerton VR. Muscle architecture of the human lower limb. Clin Orthop. 1983:275–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arkin A. Absolute muscle power: the internal kinesiology of muscle. Arch Surg. 1941:395–410. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rasch A, Bystrom AH, Dalen N, Berg HE. Reduced muscle radiological density, cross-sectional area, and strength of major hip and knee muscles in 22 patients with hip osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:505–510. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778–799. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Naimark A, Walker AM, Meenan RF. Obesity and knee osteoarthritis. The Framingham Study. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:18–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]