Abstract

Purpose

To determine the ability of the principal DTI indices to predict the underlying histopathology evaluated with immunofluorescent assay (IFA).

Materials and Methods

Conventional T2 and 3D multishot-diffusion weight echoplanar imaging (3D ms-DWEPI) was performed on a fixed, ex vivo human cervical spinal cord (CSC) from a patient with history of multiple sclerosis (MS). 170 regions of interest were selected within the white matter and categorized as a high intensity lesion (HIL), low intensity lesion (LIL), and normal appearing white matter (NAWM). The longitudinal diffusivity (λl), radial diffusivity (λr), and fractional anisotropy (FA) were obtained from each ROI. The underlying histopathology was then evaluated using immunofluorescent assay with antibodies directed to myelin and neurofilament staining.

Results

The mean values for λl, and λr, were significantly elevated within HIL relative to NAWM, and LIL. IFA analysis of HIL demonstrated significant demyelination, without significant if any axon loss. The FA values were significantly reduced in HIL, and LILs. FA values were also reduced in lesions with increased λl, and λr values relative to normal.

Conclusion

Aberrant λl, λr, and FA relative to normal values are strong indicators of demyelination. DTI indices are not specific for axon loss. IFA analysis is a reliable method to demonstrate myelin and axon pathology within the ex vivo setting.

Keywords: Diffusion tensor imaging, cervical spinal cord, multiple sclerosis, demyelination

INTRODUCTION

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) has complex pathology that involves parallel neurodegenerative and Wallerian mechanisms of axonal loss affecting different white matter tracts to varying extents, with and without the presence of concomitant myelin pathology.(1–4) Conventional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) has served as an important tool in the diagnosis of MS and for monitoring treatment progression by documenting areas of signal hyperintensity on T2 weighted imaging (T2WI) and proton density (PD) imaging. However, it has been well established that conventional MRI sequences can underestimate the actual disease burden, as reflected by the clinical manifestations of the disease and emerging post-mortem histologic correlative analysis.(5) Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) has emerged as a highly sensitive imaging method for a more specific assessment of myelin and axonal pathology that occurs in complex neurodegenerative diseases such as MS. The diffusivity measures that are derived as part of DTI scans have been increasingly utilized as potential surrogate measures of internal histopathology. The common indices utilized, assuming a cylindrical model of the spinal cord and its components, include axial or longitudinal (λl), radial or transverse diffusivity (λr), and fractional anisotropy (FA). (6) The measured λl has been proposed to be a marker for axonal disease, while the diffusivity perpendicular to axonal tracts may provide information on the integrity of myelin sheaths.(1, 5, 7–9)

Previous postmortem studies have used many different conventional MRI sequences along with basic histologic analysis to solidify the histopathology of these assumptions. Bot, Blezer, and Kamphorst et al performed histologic analysis after high-resolution T1 and T2 weighted imaging, along with magnetization transfer imaging to evaluate myelin integrity.(1) Nijeholt, Bergers, and Kamphorst et al evaluated the sensitivity of high field strength MRI to underlying histology.(5) Lovas, Szilagyi, and Majtenyi et al used Magnetic resonance spectroscopy to evaluate brain metabolites within MS lesions with histologic comparison. (2)

The objective of our study was to determine the accuracy of the principal DTI indices (λl, λr, FA) in predicting the actual underlying histopathology using immunofluorescent assay (IFA). To our knowledge, immunofluorescent assay in combination with DTI imaging has not been used previously as a method to characterize the pathology of multiple sclerosis lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical Material

A single 9 cm cervical spinal cord specimen was obtained at autopsy from a patient with multiple sclerosis, performed with written approval from family. Research on the autopsy tissues was reviewed and approved as exempt by the IRB in compliance with Department of Health and Human Services federal regulation 45CFR46. One neurologist evaluated the patient’s relevant and accessible clinical history within the University system. The patient had an aggressive form of the disease for approximately 5 years. More detailed clinical information was not available as the patient had been lost to follow-up and died from self-inflicted injuries.

Diffusion Tensor Imaging

The specimen was scanned using 3.0T Siemens scanner 3 days after being immersed in a 4 °C, 4% Paraformaldehyde and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). 3D ms-DWEPI sequence was applied on the CSC specimen using a 3T whole-body MRI system (Trio, Siemens Medical Solution, Erlangen, Germany) with Avanto gradients (45 mT/m strength and 150 T/m/s slew rate), and an institutional quadrature radiofrequency (rf) coil. (10) The MR imaging parameters were TR 400 ms, (0.5 mm)3 isotropic spatial resolution, b value of 0 and 1000 s/mm2 in 20 non-collinear directions, echotrain length (ETL) 5, and receiving bandwidth of 500 Hz/pixel. Imaging time for 3D ms-DWEPI was 30 minutes.

The acquired DTI data set was processed using DTI analysis software programmed with interactive data language (IDL). (ITT Visual Information Solutions Inc., Boulder, CO) The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) was first calculated using two images with b=0 and b=1000 s/mm2 for all 20 diffusion encoding directions. These ADC values were used to extract the 3 × 3 diffusion matrix  using the singular value decomposition (SDV), which was then diagonalized to obtain the three rotationally invariant eigenvalues (diffusivities: λ1, λ2, λ3) and the three corresponding eigenvectors. From the obtained directional diffusivities, λl, λr are defined in equation 1.

using the singular value decomposition (SDV), which was then diagonalized to obtain the three rotationally invariant eigenvalues (diffusivities: λ1, λ2, λ3) and the three corresponding eigenvectors. From the obtained directional diffusivities, λl, λr are defined in equation 1.

| [1] |

The degree of anisotropy was presented using the anisotropy indices FA (12) that is defined in equation 2.

| [2] |

Coronal T2 weighted imaging (T2WI) using 3D Turbo Spin Echo was obtained to document the lesion burden within the cervical spinal cord. The imaging parameters were TR=4000 ms, TE=81 ms, in-plane resolution=0.5 × 0.5mm2, slice thickness=0.5mm, and receiver bandwidth =255 Hz/pixel. The volumetric data was evaluated in reformatted sagittal, coronal, and axial planes.

Image Analysis

The T2WI imaging was used to identify and classify regions within the white matter columns of the cervical spinal cord specimen according to the criteria developed by Nijeholt, Bergers, and Kamphorst et al. The regions of interest (ROI) were designated by there T2 features; 1) high-signal intensity lesions (HIL), 2) low intensity lesion (LIL) with low to intermediate signal intensity isointense or hypointense to gray matter, 3) or as normal appearing white matter (NAWM).(5) ROIs, approximately 2–3mm2 in size, were then manually drawn on the axial images from the T2WI data set. The axial slice number was directly correlated with the FA map. An average of six ROIs were selected from each axial section. 170 ROIs were selected within the white matter columns from the middle length of the cord, rather than the ends. Care was made to avoid selection of the gray matter, as its diffusivity characteristics were not evaluated in this project.

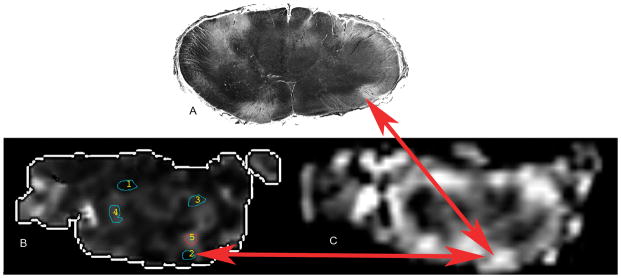

The regions of interested were then mapped to the FA data set of the corresponding axial slice. (Figure. 1) The λl, λr and FA were then obtained for each ROI. The breakdown of ROI selection is as follows: 71 HILs, 24 LILs, and 75 NAWM ROIs. A smaller number of LILs were selected due to the extent of the disease within the cord.

Figure 1.

A: Black and white image of a histologic slice axial slice with an arrow designating a white matter lesion within the anterior column, B: FA map from the corresponding slice within the cord with multiple regions of interest numbered 1 through 5, the red arrow designates the same lesion seen with routine histology, C: T2 image of the same region of cord showing the HIL within the ventral cord designated by the red arrows.

Region of Interest Analysis

The NAWM ROIs from the cord were then used as the internal control. The mean, and standard deviation values for each of the DTI parameters were established and statistically significantly different values for λl, λr, and FA were established based on a 95% CI for the Gaussian distribution of the NAWM ROIs.

Immunoflourescent assay

After completing the DTI imaging experiments the cord was for histologic evaluation. The orientation of the cord was assured by noting the projection of exiting nerve roots, cord morphology, and photo-documentation. The tissue blocks were embedded in paraffin prior to sectioning. Tissues were sliced in 20 μm thick sections and mounted, two per glass slide. Immunoflourescent assays (IFA) were performed in accordance to previously published and validated techniques.(11, 12) Primary antibodies used included a pan axonal mouse antibody to neurofilaments (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and a rabbit anti-myelin basic protein (MBP) (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corporation, Westbury, NY). Primary antibodies were diluted 1:500, according to manufacturer suggested specifications. Secondary fluorochrome antibodies were Cy5-conjugated anti-mouse, and anti-rabbit, FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit (Jackson

Images were acquired with the Personal Confocal Microscopy PCM-2000 (Nikon, Melville, NY). The FITC label was detected with the Argon laser at 488 nm and Cy5 with a red HeNe laser at 633 nm. Simple Personal Confocal Image Program (PCI, Compix, Cranberry Township, PA), a multifocus (z-focus) program, was used to create a stereopsis image. Tissues were individually scanned for each respective fluorochrome. The separate images were then merged to create the final two-colored image and allowing for comprehensive visualization of labeling throughout the tissue. The regions of interest were then matched to the IFA images using available anatomic landmarks, and the morphology of the gray matter just as the basic histology sections were matched.

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained was analyzed using Excel 2008 for Macintosh and Matlab 7.9 for Macintosh. One-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate for differences in the principal diffusivities between the three categories of ROIs selected.

RESULTS

MRI and DTI analysis

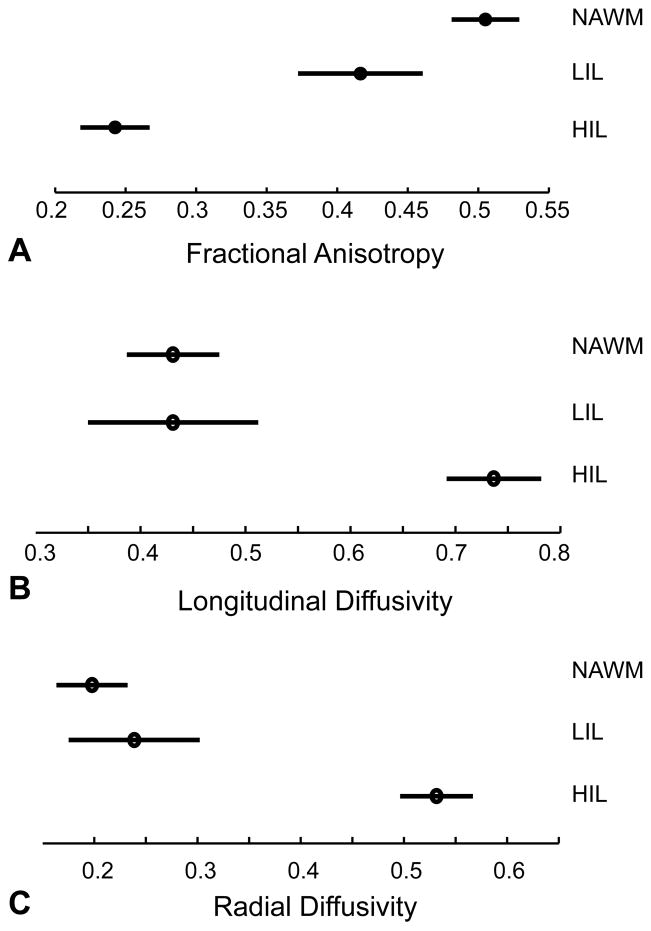

The average values for each ROI category are summarized in table 1 and figure 2. One-way ANOVA evaluation showed a significant difference in measured λl, λr, and FA values when comparing HIL to both LIL and NAWM ROIs. However there was no significant difference between the measured diffusivities between the NAWM and LIL ROIs.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for λl, λr, and FA from the selected ROIs.

| Groups | Sample size | Mean | Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| FA | |||

| HIL | 71 | 0.2416 | 0.0094 |

| NAWM | 76 | 0.5026 | 0.024 |

| LIL | 24 | 0.4094 | 0.0094 |

| λl | |||

| HIL | 71 | 0.7337 | 0.0999 |

| NAWM | 76 | 0.4312 | 0.0226 |

| LIL | 24 | 0.4236 | 0.018 |

| λr | |||

| HIL | 71 | 0.5303 | 0.069 |

| NAWM | 76 | 0.1992 | 0.0072 |

| LIL | 24 | 0.2384 | 0.0101 |

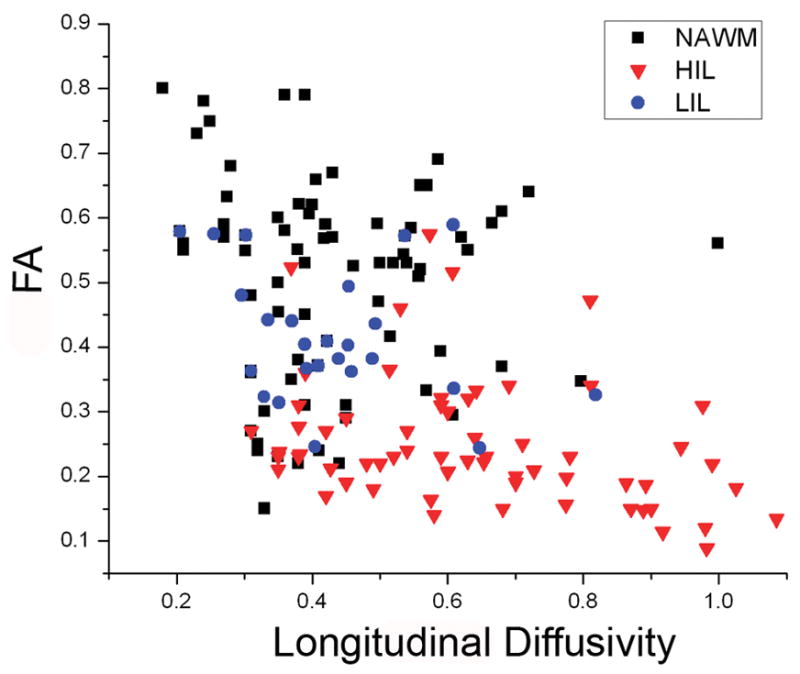

Figure 2.

Analysis of variance from measured FA (A), λl (B), and λr(C) between the ROI categories.

Next, using the measured normal values of the λl, λr, and FA values from ROIs from the normal white matter, the rest of the ROIs were then categorized according to the whether each index was normal, increased, or decreased based on the 95% CI from the distribution of NAWM ROIs. (Table 2.) Of the HIL selected for evaluation (N=71), 58% demonstrated an increase in both λl and λr. A smaller proportion (23%) had normal λl and an increased λr, or 14% had decreased λl and normal λr.

Table 2.

Summary of patterns of diffusivity indices for the selected ROIs divided by ROI type.

| Diffusivity Patterns | Total | HIL | LIL | NAWM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Normal λl and λr | 25 | 2 | 6 | 17 |

| 2. Normal λl and increased λr | 22 | 16 | 1 | 5 |

| 3. Normal λl and decreased λr | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 4. Increased λl and normal λr | 6 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 5. Increased λl and λr | 50 | 41 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. Increased λl and decreased λr | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7. Decreased λl and normal λr | 28 | 10 | 5 | 13 |

| 8. Decreased λl and λr | 30 | 0 | 4 | 26 |

| 9. Decreased λl and increased λr | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The LIL ROIs (N=24) showed a great degree of variability in the diffusivity patterns measured. 30% did not have any significant differences in the measured λl and λr diffusivities compared to the internal control. 13% had increased λl and λr, while 48% of the ROIs showed a decreased λl, and either a normal or decreased λr based on a p-value of 0.05.

The combined lesion analysis (N=95) showed that 50% of both HIL and LIL had a pattern of increased λl and λr diffusivity. 14% of all lesions evaluated had a significantly decreased λl diffusivity when compared to the internal control. The remaining ROIs showed significant variability in the measured values relative to normal.

Further correlative analysis was performed using the measured FA compared to lesion type. It was found the FA was generally decreased across all lesion types, most significantly with HIL lesions. These lesions also had corresponding significant increase in the λl. (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Correlation plot of longitudinal diffusivity and FA showing that HIL have an overall decreased measured FA.

Immunoflourescent Assay

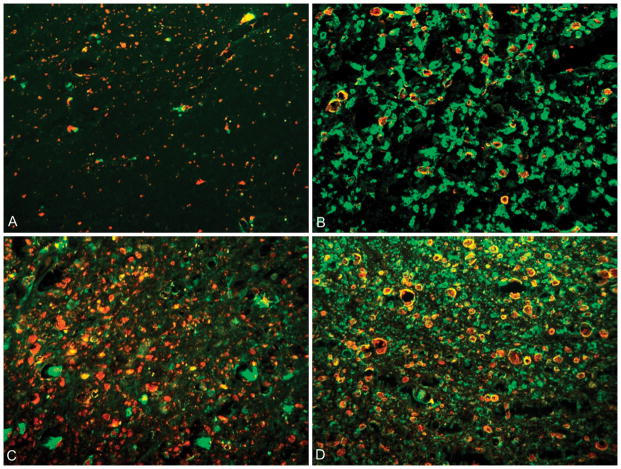

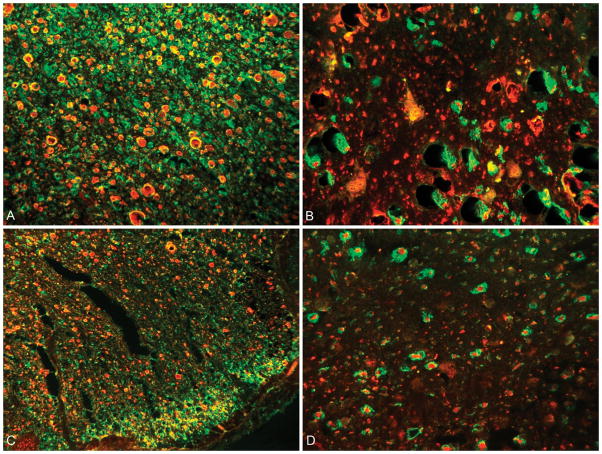

A neuropathologist evaluating the degree of demyelination and axonopathy determined four distinct patterns of antibody localization described in figure 4. The green FITC fluorochrome is attached to antibodies directed toward predominantly intact myelin. Antibodies directed to the neurofilaments are labeled with a red Cy5 fluorochrome. When co-labeling of the FITC and Cy5 antibodies occurred, the resultant color displayed is yellow, indicating intact myelin and neurofilament.

Figure 4.

Dual labeling of axons (red fluorochrome) and myelin (green fluorochrome). A: Pattern 1 shows complete loss of myelin with scattered areas of axon preservation; B: Pattern 2 demonstrates loss of axons with relative myelin preservation; C: Pattern 3 has preserved axons with decreased myelin; D: Pattern 4 represents an area of normal myelin and axonal integrity with co-localization (yellow) of the red and green fluorochrome.

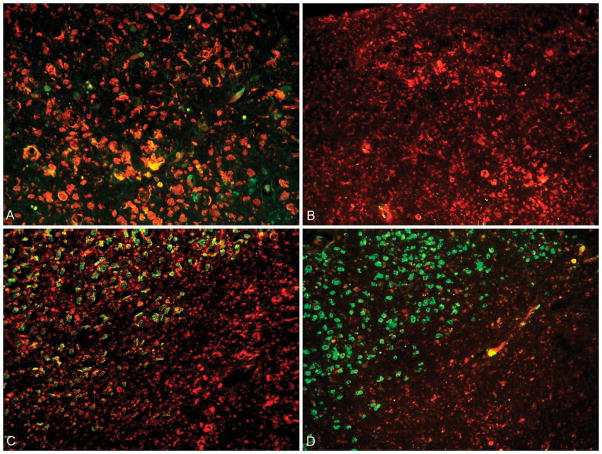

The three lesions types (HIL, LIL, and NAWM) defined based on the T2WI were then compared to the corresponding area within the cervical cord within serial sections. High intensity lesions, showed significant demyelination and varying degrees of neurofilament destruction. Representative findings found in most HIL are shown in figure 5. The margins of HIL were found to have relative myelin preservation. Low intensity lesions and NAWM showed variable levels of demyelination with general axonal preservation, representative findings shown in figure 6.

Figure 5.

A: 40X magnification of a HIL from the anterior column showing complete loss of myelin along the superior part of the image, areas of co-localization of intact myelin and axons (yellow) centrally within the image; B: Low power (20X) of HIL with complete loss of myelin and axon preservation (Pattern 1); C: 20X magnification showing the margin of a HIL in the upper left corner (Pattern 3) transitioning to a chronic lesion within the lower right corner (Pattern 1); D: 20X image of a HIL within the lower right (Pattern 1), and the lesion margin in the upper left showing decreased axons and preserved myelin (Pattern 2).

Figure 6.

A: 20X magnification of a NAWM ROI showing normal axons and myelin (Pattern 4); B: 60X magnified view of a region of NAWM based on MRI imaging showing areas of demyelination centrally within the image (Pattern 3); C: Low power view (20X) showing relative decrease in the number of axons (Pattern 2); D: 60X view of the margin of a LIL showing islands of co-localizing antibodies (yellow) surrounded by demyelinated axons (Pattern 1).

DISCUSSION

Prior research has shown that λl can been used as a marker for axonal integrity. Reduced λl values have been associated with decreased axonal density within the brain and spinal cord. (1, 7, 8, 13–15) DeLuca, Williams, and Evangelou et al have also demonstrated that a normal λl can be found despite the presence of demyelination and or axon loss due to loss of small caliber axons and relative preservation of large caliber axons. Based on these assertions, we expected HIL to have statistically significant reduction in λl indicating axon loss. However we found that the mean λl from the HIL was significantly increased relative to normal. The opposite of some previously published results. (6–8, 13, 15, 16) In fact none of the HIL evaluated had a statistically significant decrease in the measured λl. (Table 2) The most striking and common feature of the HIL evaluated with IFA analysis was that of extensive demyelination, with axonal loss being a less conspicuous observation. (Figure 5.B.) These findings suggest that it is mainly demyelination rather than axon injury that contributes to the λl within MS lesions. Alternatively, the increase in λl found within the HIL, may be secondary to preferential loss of small caliber axons, and large diameter axon preservation. This theory was not evaluated as part of the current study, but will be investigated as part of further research at out institution.

Radial diffusivity has been used as a noninvasive measure of myelin in both in vivo and ex vivo DTI experiments. (1, 5, 17) Animal studies have supported this supposition by showing that demyelination causes an increased λr without affecting λl.(7) We theorized that if the λr was normal for a given ROI, the myelin would be normal on both routine histology and IFA analysis. Similarly, an increased λr was expected to represent areas of demyelination. Our results show that λr is significantly increased in HIL, and decreased in both LIL and NAWM. IFA analysis (Figure 5) confirmed complete loss of myelin centrally within HIL with areas of relative myelin sparing along lesion margins. IFA analysis of the LIL showed two predominant patterns of antibody localization (Figure 6.D), that of incomplete or “active” demyelination with relative axon sparing. The NAWM ROIs had similar findings, as well as more areas that were essentially normal. (Figure 6.A–C).

The fractional anisotropy has been used in monitoring MS patients as a progressive decrease in FA has been correlated with increasing disability. Many neurologic disease processes within the brain and spinal cord have been shown to cause a decrease in FA. (14–16, 18) Fractional anisotropy values represent the overall anisotropy of the structures being evaluated. It is highly dependent on the behavior of water molecules within the extracellular space surrounding axons within white matter tracts. FA was significantly decreased in HIL, mildly decreased in LIL, and normal with NAWM ROIs. Renoux Facon, and Fillard et al suggested that FA is decreased from local extracellular edema and or decreased number of axons in areas white matter lesions. (19) Our results however imply that demyelination is the main factor causing a low FA. This is supported by our findings of significantly increased longitudinal and radial diffusivities within HIL. Additional ex vivo as well as in vivo publications have found that FA is the most robust index for demyelination. (20, 21)

It was our prediction, based on prior research discussed above that a majority of the HIL and LIL ROIs would demonstrate reduced λl diffusivity and increased λr diffusivities, which would indicate demyelination and axon loss. (1, 8, 13) However the pattern of decreased λl and increased λr was not demonstrated among any of the selected ROIs. Instead the predominant pattern found among all lesions (50% of HIL and LIL lesions) was that of both increased λl and λr diffusivities. This pattern would indicate, based on prior work, that along with demyelination there is some degree of preferential loss of small diameter axons. (1, 22) 40% of all the ROIs (N=167) showed a decrease in λl, a finding which past studies suggest results from a loss of axons. (1, 8) Again however, IFA analysis of both HIL lesions in this cord showed mainly demyelination.

The next goal of our work was for accurate characterization of NAWM, as this has many potential clinical implications. Accurate and reliable evaluation of NAWM would allow for early treatment intervention, and more sensitive treatment monitoring. Our findings were consistent with several other publications describing a great deal of pathology within NAWM that is occult on conventional imaging. (23) Half of the NAWM ROIs (38/75) had a decreased λl relative to normal. A finding that may be secondary to axonal pathology. Axonal loss has been documented to occur in regions of NAWM in previous ex vivo spinal cord specimens.(2) Additionally, 46% of NAWM ROIs had λr values that indicated myelin loss (increased λr). This is an interesting finding as the abnormal values where measured without any apparent T2 signal abnormality. These regions may represent “prelesion” areas that may eventually progress to fulminate demyelination and axonal loss. NAWM regions in the spinal cord of multiple sclerosis patients have been shown to have areas of microglia recruitment, perivascular inflammation, and regions of myelin breakdown contributing to an increase water in the extracellular space and decreased FA.(22, 24) These NAWM regions with increased λr diffusivity show the most promise for a potential target of treatment. IFA analysis confirmed that NAWM regions have varying degrees of demyelination and axon loss. (Figure 6.A–C)

The final objective was to develop methodology to allow a better understanding of the utility of DTI. Implicit in our primary goal was to see if the measured DTI parameters accurately described the actual histopathology. We found that the sensitivity of our MRI-DTI techniques was very high on a qualitative basis relative the IFA evaluation. It has been well established that the signal intensity of T2 lesions correlate to the degree of inflammation and myelinopathy. (2) The HIL and LIL found with MRI demonstrated morphologic features that could be readily recognized and evaluated using both conventional histology and IFA. This has been shown to be a feasible method by Gilmore, Geurts, Evangelou et al.(25) We believe that the quality of our histology and IFA results were similar to results published by Nijeholt, Bergers, and Kamphorst et al and Nagao, Ogawa, and Yamauchi et al. (5, 26) Because of the high quality of our MRI data and the reliable correlation with histological sections, we were able to compare measured diffusivity values with the actual regions of the specimen. In order to determine if λl, λr, were abnormal, normal values needed to be established. It was felt that establishing an internal normal control was important to maintain consistency. A different cord specimen may have variable hydration, or fixation effects that could affect direct comparison. Additionally, because the measurement of diffusivity values is highly dependent on SNR, we were able to maintain a constant SNR by using internal normal diffusivity values.(27)

Our analysis was limited by our ability to accurately manually co-localize the ROIs from both the T2 imaging to the corresponding area on the FA maps. There was an unavoidable discrepancy in accurately localizing the ROIs from the MRI-DTI imaging that results from the different slice thickness between the two methods. We relied on the severity of the lesion burden and the fact that the lesions were longitudinally oriented within the white matter columns. Because of the nature of the data, the complexity of analysis between multiple measured values, diffusivity pattern analysis, and histology evaluation, only a qualitative analysis was performed to analyze the correlation between the DTI findings and IFA results.

A potential criticism for working with ex vivo is that fixation may alter diffusivity values over time.(28) However, we do not believe this to be a problem with our specimens, as recent publications have shown that once adequately fixed, the diffusivity values remain stable. (29, 30) In addition to fixation, specimen was scanned in a temperature controlled setting to avoid heating and potential tissue destruction. Temperature is known to affect SNR, and likely accounts for the smaller magnitude of measured diffusivities. (27)

In conclusion, the findings suggest that FA is the most robust index derived from DTI analysis in predicting demyelination. No single diffusivity parameter reliably predicts axon loss, namely aberrant λl values did not strongly correlate with axon pathology as has been previously suggested. Furthermore, IFA is a highly specific method for evaluating myelin and axonal pathology. IFA has additional potential to evaluate for inflammatory substrates in addition to myelin and axons which may help to improve our recognition of potential targets for treatment.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the Cumming Foundation, the Benning Foundation, and NIH grants R21NS052424 and R21EB005705

Footnotes

Presented ASNR 48th Annual Meeting, May 20th, 2010. RE: 494 - Diffusion Tensor Imaging of the Cervical Spinal Cord Ex Vivo: Evaluating the Association between Aberrant Principle Diffusivities and Histopathology Using Immunoflourescent Assay

References

- 1.Bot JC, Blezer EL, Kamphorst W, et al. The spinal cord in multiple sclerosis: relationship of high-spatial-resolution quantitative MR imaging findings to histopathologic results. Radiology. 2004;233:531–540. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2332031572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovas G, Szilagyi N, Majtenyi K, Palkovits M, Komoly S. Axonal changes in chronic demyelinated cervical spinal cord plaques. Brain. 2000;123 (Pt 2):308–317. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Filippi M, Bozzali M, Rovaris M, et al. Evidence for widespread axonal damage at the earliest clinical stage of multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2003;126:433–437. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filippi M, Iannucci G, Cercignani M, Assunta Rocca M, Pratesi A, Comi G. A quantitative study of water diffusion in multiple sclerosis lesions and normal-appearing white matter using echo-planar imaging. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1017–1021. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.7.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nijeholt GJ, Bergers E, Kamphorst W, et al. Post-mortem high-resolution MRI of the spinal cord in multiple sclerosis: a correlative study with conventional MRI, histopathology and clinical phenotype. Brain. 2001;124:154–166. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark CA, Werring DJ, Miller DH. Diffusion imaging of the spinal cord in vivo: estimation of the principal diffusivities and application to multiple sclerosis. Magn Reson Med. 2000;43:133–138. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(200001)43:1<133::aid-mrm16>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song SK, Sun SW, Ramsbottom MJ, Chang C, Russell J, Cross AH. Dysmyelination revealed through MRI as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1429–1436. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLuca GC, Williams K, Evangelou N, Ebers GC, Esiri MM. The contribution of demyelination to axonal loss in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2006;129:1507–1516. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nijeholt GJ, van Walderveen MA, Castelijns JA, et al. Brain and spinal cord abnormalities in multiple sclerosis. Correlation between MRI parameters, clinical subtypes and symptoms. Brain. 1998;121 (Pt 4):687–697. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeong EK, Kim SE, Parker DL. High-resolution diffusion-weighted 3D MRI, using diffusion-weighted driven-equilibrium (DW-DE) and multishot segmented 3D-SSFP without navigator echoes. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:821–829. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill KE, Zollinger LV, Watt HE, Carlson NG, Rose JW. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in chronic active multiple sclerosis plaques: distribution, cellular expression and association with myelin damage. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;151:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsoi VL, Hill KE, Carlson NG, Warner JE, Rose JW. Immunohistochemical evidence of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in a case of clinically isolated optic neuritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2006;26:87–94. doi: 10.1097/01.wno.0000223266.48447.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trapp BD, Peterson J, Ransohoff RM, Rudick R, Mork S, Bo L. Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:278–285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801293380502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agosta F, Absinta M, Sormani MP, et al. In vivo assessment of cervical cord damage in MS patients: a longitudinal diffusion tensor MRI study. Brain. 2007;130:2211–2219. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agosta F, Benedetti B, Rocca MA, et al. Quantification of cervical cord pathology in primary progressive MS using diffusion tensor MRI. Neurology. 2005;64:631–635. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151852.15294.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agosta F, Rovaris M, Benedetti B, Valsasina P, Filippi M, Comi G. Diffusion tensor MRI of the cervical cord in a patient with syringomyelia and multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1647. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.042069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim TH, Zollinger L, Shi XF, et al. Quantification of diffusivities of the human cervical spinal cord using a 2D single-shot interleaved multisection inner volume diffusion-weighted echo-planar imaging technique. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;31:682–687. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hesseltine SM, Law M, Babb J, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in multiple sclerosis: assessment of regional differences in the axial plane within normal-appearing cervical spinal cord. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1189–1193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Renoux J, Facon D, Fillard P, Huynh I, Lasjaunias P, Ducreux D. MR diffusion tensor imaging and fiber tracking in inflammatory diseases of the spinal cord. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:1947–1951. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mottershead JP, Schmierer K, Clemence M, et al. High field MRI correlates of myelin content and axonal density in multiple sclerosis--a post-mortem study of the spinal cord. J Neurol. 2003;250:1293–1301. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-0192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Hecke W, Nagels G, Emonds G, et al. A diffusion tensor imaging group study of the spinal cord in multiple sclerosis patients with and without T2 spinal cord lesions. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;30:25–34. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evangelou N, DeLuca GC, Owens T, Esiri MM. Pathological study of spinal cord atrophy in multiple sclerosis suggests limited role of local lesions. Brain. 2005;128:29–34. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo AC, MacFall JR, Provenzale JM. Multiple sclerosis: diffusion tensor MR imaging for evaluation of normal-appearing white matter. Radiology. 2002;222:729–736. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2223010311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Werring DJ, Brassat D, Droogan AG, et al. The pathogenesis of lesions and normal-appearing white matter changes in multiple sclerosis: a serial diffusion MRI study. Brain. 2000;123 (Pt 8):1667–1676. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.8.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilmore CP, Geurts JJ, Evangelou N, et al. Spinal cord grey matter lesions in multiple sclerosis detected by post-mortem high field MR imaging. Mult Scler. 2009;15:180–188. doi: 10.1177/1352458508096876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagao M, Ogawa M, Yamauchi H. Postmortem MRI of the spinal cord in multiple sclerosis. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:625–626. doi: 10.1007/BF00600425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierpaoli C, Basser PJ. Toward a quantitative assessment of diffusion anisotropy. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36:893–906. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JH, Trinkaus K, Ozcan A, Budde MD, Song SK. Postmortem delay does not change regional diffusion anisotropy characteristics in mouse spinal cord white matter. NMR Biomed. 2007;20:352–359. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim TH, Zollinger L, Shi XF, Rose J, Jeong EK. Diffusion tensor imaging of ex vivo cervical spinal cord specimens: the immediate and long-term effects of fixation on diffusivity. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2009;292:234–241. doi: 10.1002/ar.20823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmierer K, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Tozer DJ, et al. Quantitative magnetic resonance of postmortem multiple sclerosis brain before and after fixation. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:268–277. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]