Abstract

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMFT) is a relatively uncommon neoplasm with unpredictable malignant potential known to occur anywhere in the body. IMFT involving the omentum is a very rare entity with less than 15 cases reported so far. We report a case of omental IMFT in a 15-year-old girl who presented with multiple peritoneal masses on imaging and the diagnosis was confirmed on histopathology. In addition to its uncommon location, its presentation as multiple masses is extremely uncommon. This uncommon presentation as multifocal masses needs to be distinguished from other causes of peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Keywords: Inflammatory pseudotumour, omentum, peritoneal carcinomatosis, smooth muscle actin, anaplastic lymphoma kinase

Introduction

Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour (IMFT) more commonly known as inflammatory pseudotumour is a relatively rare tumour with variable malignant potential. Typically seen in children and young adults it can occur anywhere in the body but is commonly described in the lungs, mediastinum and orbits. Intraabdominal IMFT commonly involves liver, stomach, bowel and spleen[1]. We report a case of multifocal intraabdominal IMFT involving the omentum and mesentery presenting as multiple peritoneal masses similar to peritoneal carcinomatosis. Omental IMFT itself is a relatively rare form of abdominal IMFT; less than 15 cases have been reported in the world literature[2,3]. Omental IMFT presenting as multiple masses is extremely uncommon and to the best of our knowledge, a similar case has not been reported to date.

Case report

A 15-year-old adolescent girl was referred to our hospital with abdominal pain, intermittent fever and loss of weight for the past 3 months. She also had amenorrhoea for the last 4 months. Physical examination revealed pallor. A vague lower abdominal mass was felt on clinical examination. Laboratory investigations showed reduced haemoglobin (9.3 g/dl); other investigations (total leukocyte count, differential count, eosinophil sedimentation rate (ESR), serum proteins) were within normal limits.

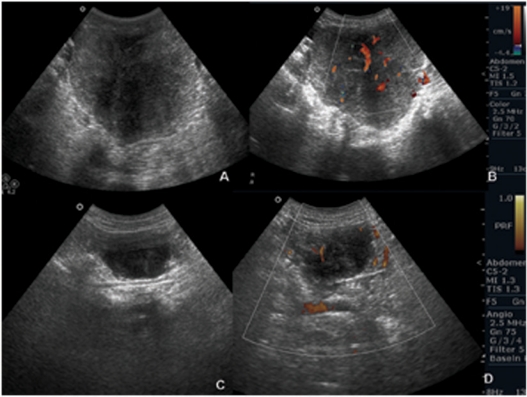

Ultrasound (US) of the abdomen showed a solid hypoechoic mass in the pelvis along the left superior aspect of the uterus with intralesional vascularity on colour Doppler (Fig. 1a,b). Multiple lesions with similar features but of varying sizes were also seen on the parietal peritoneum with mild free fluid in the pelvic cavity (Fig. 1c,d). The uterus and ovaries were visualized separately.

Figure 1.

US images show heterogeneous hypoechoic lesions in the pelvis (a) and on the parietal peritoneum (c). Note internal vascularity on colour Doppler (b,d).

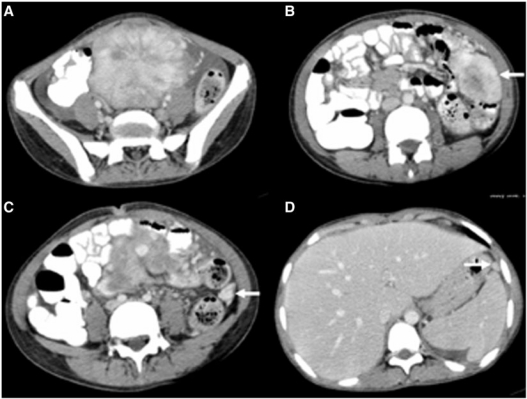

Following US, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was done to characterize and assess the extent of the mass. It showed a large (7.2×6.3 cm), lobulated, well-marginated, hypervascular mass in the pelvis displacing the pelvic bowel loops with minimal ascites (Fig. 2a). In addition, multiple peritoneal-based lesions with similar characteristics but of varying sizes were also noted (Fig. 2b–d). Radiologically the lesions mimicked those of carcinomatosis. A differential diagnosis of sarcoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST), leiomyoma, lymphoma, inflammatory pseudotumour and Castleman’s disease was made. US-guided fine needle aspiration cytology revealed scattered spindle cells and occasional multinucleated giant cells with no evidence of malignancy. As a definite diagnosis could not be reached, exploratory laparotomy was planned. Intraoperatively, a large lobulated vascular mass was seen arising from the greater omentum adherent to the sigmoid colon which was excised completely. Multiple pelvic deposits with ascites were also noted which were too numerous for resection. The patient recovered uneventfully from surgery.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT images show a lobulated hypervascular lesion in the pelvis with free fluid (a). Note multiple peritoneal-based lesions (arrows) (b–d).

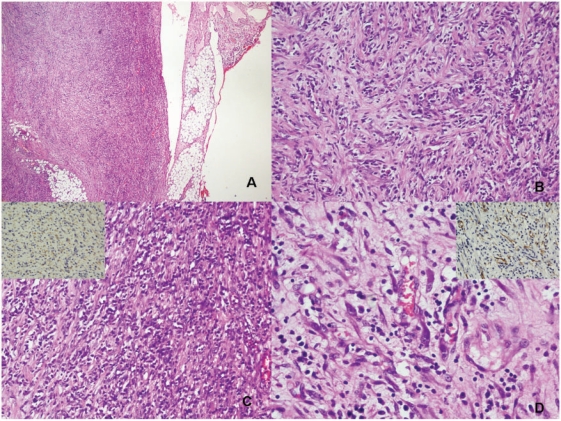

Histopathological evaluation of the resected tumour showed a well-circumscribed mass with a dominant spindle cell tumour admixed with moderate chronic inflammatory cells. The spindle cells were arranged haphazardly in a myxoid background but some areas were arranged in fascicles (Fig. 3a–d). Occasional cells showed a moderate eosinophilic cytoplasm indicating their myofibroblastic nature. These cells demonstrated anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) (Fig. 3c, inset top left) and smooth muscle actin (SMA) positivity (Fig. 3d, inset top right). There were no significant mitotic figures seen in the spindle cell areas. A diagnosis of IMFT was made. The lesions being numerous no further treatment (surgical, radiotherapy or chemotherapy) was offered. The patient is on radiologic surveillance.

Figure 3.

(a) The periphery of the tumour with infiltration into fat (H&E); (b) spindle-shaped tumour cells in short interlacing fascicles admixed with moderate chronic inflammatory cells rich in plasma cells (H&E); (c) spindle cell populations with plasma cell infiltrate with the tumour cells showing cytoplasmic ALK positivity (inset: ALK immunostaining); and (d) some tumour cells are elongated with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm (H&E) showing SMA positivity (inset: SMA immunostaining) indicating the myofibroblastic nature.

Discussion

IMFT is a rare tumour of intermediate biologic potential as described in the recent WHO classification. It has been variously called inflammatory pseudotumour, inflammatory fibrosarcoma, plasma cell granuloma, pseudosarcoma, and atypical fibromyxoid tumour. Initially described in the lungs and orbit as a reparative postinflammatory process, it has now been reported in many other extrapulmonary sites. The pathogenesis of this condition has been variously described as an excess inflammatory response to infection, trauma, and surgery. The abdomen is a relatively uncommon site for IMFT; the liver is the organ most often involved. It can occur in both genders and is seen in children and adolescents. Historically these tumours were considered benign until Meis and Enzinger published a series of 38 cases, primarily intraabdominal, with follow-up data showing significant recurrences. They renamed the pathology inflammatory fibrosarcoma[2]. Omental IMFT has been described as a distinct entity from the common inflammatory pseudotumour of the abdomen as pathologically it represents a form of clonal expansion rather than a postinflammatory response[1].

Abdominal IMFTs are more confusing from both diagnostic and therapeutic aspects, as they are commonly mistaken for malignant tumours such as peritoneal carcinomatosis, sarcoma or lymphoma. Patients generally present with nonspecific systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and vague abdominal pain. Specific symptoms depend on the size of the tumour and the mass effect on the adjacent structures. Laboratory evaluation may reveal hypergammaglobulinemia, false-positive Widal test, increased ESR, thrombocytosis, and microcytic anaemia.

Radiologic findings of omental-mesenteric IMFT are indistinguishable from other malignant lesions. On sonography they are seen as solid iso- to hypoechoic masses with vascularity on Doppler. On CT they are variously described as homo- or heterogeneous hypervascular lesions showing moderate to intense enhancement. Calcification, haemorrhage and necrosis are reported in a few cases[4]. The top differentials include sarcoma, lymphoma, GIST, Castleman’s disease and all causes of peritoneal carcinomatosis in the case of multiple masses[5]. It is important to differentiate as many of these close differentials need aggressive treatment with cytotoxic drugs, which may be harmful and could be avoided if a correct diagnosis is established. The diagnosis can rarely be made with imaging alone. Histology findings of diffuse inflammatory infiltration, prominent plasma cells on microscopy and actin, vimentin positivity on immunohistochemistry confirm the diagnosis[6].

After the diagnosis is made it becomes necessary to assess the prognosis. There are limited data available on the natural history of this disease. Features suggesting more aggressive behaviour include multifocal tumours, retroperitoneal location, infiltration of adjacent structures and incomplete excision. Pathologic features such as tumour cellularity, mitosis and necrosis do not correlate with outcome. Recently ALK positivity has been shown to predict lower risk of metastasis[7].

Treatment includes complete excision of tumour. The role of radiotherapy and chemotherapy is very limited. Resection is the treatment of choice even for recurrences. Recurrences have been reported even after many years, so regular follow-up is essential for early diagnosis of tumour recurrence.

Footnotes

This paper is available online at http://www.cancerimaging.org. In the event of a change in the URL address, please use the DOI provided to locate the paper.

References

- 1.Treissman SP, Gillis DA, Lee CL, et al. Omental-mesenteric inflammatory pseudotumor. Cytogenetic demonstration of genetic changes and monoclonality in one tumor. Cancer. 1994;73:1433–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940301)73:5<1433::AID-CNCR2820730518>3.0.CO;2-F. . PMid:8111710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meis JM, Enzinger FM. Inflammatory fibrosarcoma of the mesentery and retroperitoneum. A tumor closely simulating inflammatory pseudotumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:1146–56. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199112000-00005. . PMid:1746682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Day DL SS, Dehner LP. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the mesentery and small intestine. Pediatr Radiol. 1986;16:210–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02456289. . PMid:3703596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim SJ, Kim WS, Cheon JE, et al. Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors of the abdomen as mimickers of malignancy: imaging features in nine children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:1419–24. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.2433. . PMid:19843762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levy AD, Shaw JC, Sobin LH. Secondary tumors and tumorlike lesions of the peritoneal cavity: imaging features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29:347–73. doi: 10.1148/rg.292085189. . PMid:19325052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta CR, Mohta A, Khurana N, et al. Inflammatory pseudotumor of the omentum: an uncommon pediatric tumor. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:219–21. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.48924. PMid:19332919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bridge JA, Kanamori M, Ma Z, et al. Fusion of the ALK gene to the clathrin heavy chain gene, CLTC, in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:411–15. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61711-7. . PMid:11485898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]