Abstract

The study and therapy of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of blindness worldwide, have taken great strides over the past decade. During the same time, a central role for RNA in many human diseases has been discovered. We have identified anti-angiogenic functions for synthetic double stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) in neovascular AMD and cytotoxic functions for endogenous dsRNAs in atrophic AMD. These findings provide new insights into the pathogenesis and therapy of both forms of AMD.

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a worldwide epidemic with an estimated prevalence of 30 to 50 million1–4 that rivals that of Alzheimer's disease5 and that of all cancers combined.6 AMD is misconceived of as a disease of just the elderly. In fact, even middle-aged individuals are at risk: For example, a 50-year-old American woman is four times more likely to be diagnosed with AMD than breast cancer before she reaches the age of 55.7,8

The principal cause of severe vision loss in patients with AMD is the invasion of aberrant blood vessels into the retina from the choroid, a pathologic event termed choroidal neovascularization (CNV). In years past, the diagnosis of CNV was a death knell for central vision, as its natural history was often one of an inexorable decline of foveal acuity. Fortunately, the past decade has witnessed a succession of ever-better molecular therapies that have dramatically altered the visual trajectory of patients with CNV. First came photodynamic therapy with benzoporphyrin (verteporfin, Visudyne; Novartis, Basel, Switzerland)9 and then pegaptanib (Macugen; Pfizer, New York, NY),10 an aptamer targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A. Both therapies stemmed the severity of vision loss. The introduction of ranibizumab (Lucentis; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA), an anti–VEGF-A antibody Fab fragment, and the subsequent use of bevacizumab (Avastin; Genentech), a full-length anti–VEGF-A antibody, has fundamentally altered the clinical management of CNV, as these drugs were the first to improve vision on an aggregate mean basis.11–13

Still, anti–VEGF-A antibody therapy is not a panacea, as only one third of patients recover driving vision, whereas one sixth progress to registered blindness. Thus, there is tremendous interest in developing alternative therapeutic strategies. One such approach that generated tremendous excitement is small interfering (si)RNA therapy, a concept that capitalized on the revolutionary discovery of endogenous intracellular machinery that employs short, double-stranded (ds)RNAs to target specific mRNAs for cleavage and degradation.14 The introduction of siRNAs, which are synthetic chemical structures mimicking endogenous short dsRNAs, into the cell can replicate this naturally occurring process of RNA interference (RNAi).15

It is notable that the first human trials of siRNAs were conducted in the eye. siRNAs targeting VEGF-A (bevasiranib) or one of its receptors VEGFR-1 (siRNA-027/AGN 211745) were tested as intravitreously administered drug candidates in clinical trials in patients with CNV due to AMD. Interestingly, neither of these siRNAs was formulated for cell permeation, which is a requirement for executing the intracellular process of RNAi. Indeed, several studies have demonstrated that 21-nt siRNAs do not permeate mammalian cells unless they are specially formulated to do so.16–22 Current approaches to executing bona fide RNAi using siRNAs use conjugation to cholesterol moieities, encapsulation by liposomes or nanoparticles, transfection with chemical or viral delivery agents or other similar modalities. However, bevasiranib and siRNA-027/AGN 211745 are naked siRNA entities that are incapable of entering mammalian cells and therefore are incompetent to execute RNAi. Their reported antiangiogenic effects in experimental models of CNV were thus surprising.23,24 Hence, we reexamined the mechanism of action of siRNAs in the laser injury-induced model of CNV, to which we devote the next section.

Analyzing CNV

Laser injury as an experimental model of CNV was introduced in a series of foundational manuscripts by Ryan.25 Subsequently, this model was extended to rats, pigs, and mice. Although the model is not synonymous with CNV development in patients with AMD, it does replicate many of the salient molecular and pathologic features of AMD-related CNV.26 Notably, excessive laser photocoagulation also induces CNV in humans.

The size of the laser-induced CNV lesion has been estimated by measuring its thickness (height) in histologic sections or by measuring either its area or volume. The latter measurements are aided by staining choroidal endothelial cells using antibodies against endothelial cell markers or various lectins with affinity for endothelial cells. Measurements of thickness inevitably suffer from many selection and orientation biases. Measurements of area can, as seen in Figure 1 and, as has been long recognized,27,28 vary greatly, depending on the precise focal plane being imaged, and can lead to misinterpretation of actual lesion size. Therefore, our laboratory,29–34 as well as that of others,35,36 employs volumetric analysis in recognition of the three-dimensional geometry of the CNV lesion.

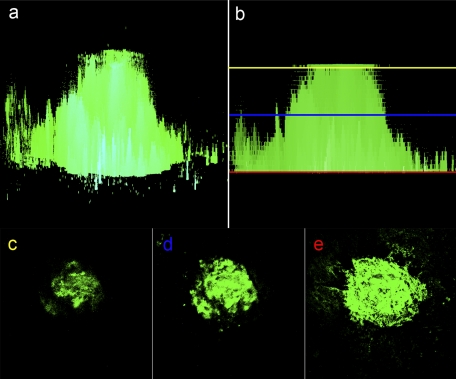

Figure 1.

Calculating CNV using area measurements may lead to artifactual differences, as determined by precise focal plane during imaging. CNV lesion size is most accurately measured using volumetrics whereby areas derived from a z-stack of focal plane images are summed from the most anterior to posterior plane of the lesion, as seen in the orthogonal section of an FITC-lectin stained choroid 7 days after laser injury (a). When CNV lesion size is calculated by using area-based methodology, there may be large artifactual differences due to the observer choice of focal plane from which the image slice is taken. Thus, depending on whether the operator chosen image slice is selected from the anterior (yellow line), middle (blue line), or posterior (red line) aspect of the lesion (b), there will be large variation in the final area measurement (c–e).

The “activity” of the CNV lesion is often assessed by fluorescein angiography. Similar to angiography studies in humans, sodium fluorescein is injected intravenously, and a time series of images is captured through the dilated pupil. We have proposed a four-point scale to introduce a quantitative element to the interpretation of angiographic leakage patterns.32 Still, it should be recognized that this readout is, at best, semiquantitative. A robust quantitative measure of CNV activity or leakage has not yet been established.

siRNAs Have Generic Antiangiogenic Activity

Our initial experiments confirmed that intravitreous administration of 21-nt siRNAs whose sequences were identical with bevasiranib and siRNA-027/AGN 211745 reduced CNV volume and leakage in C57BL/6J (B6) mice. However, we were puzzled when various “control” siRNAs also suppressed CNV. Regardless of whether these control siRNAs targeted nonmammalian genes such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) or firefly luciferase (Luc), mammalian genes not expressed in the eye such as bone-specific osteocalcin, kidney-specific cadherin 16, and lung-specific surfactant protein B or random sequences not found in any sequenced genome, we found that 21-nt siRNAs uniformly suppressed CNV. This sequence- and target-independent effect led us to hypothesize that a pattern recognition response was responsible. We focused on toll-like receptor-3 (TLR3), a member of the TLR family of pathogen associated molecular pattern recognition receptors that was known to recognize long viral dsRNAs.37

We observed that 21-nt siRNAs did not reduce CNV volume in Tlr3–/– mice and that anti-TLR3 neutralizing antibodies blocked the antiangiogenic effect in B6 wild-type mice. We also found, using flow cytometry and immunofluorescent localization, that TLR3, which originally was localized to endosomal structures in immune cells, is also expressed on the cell surface of both choroidal endothelial cells and retinal pigmented epithelial cells. These findings argued that 21-nt naked siRNAs incapable of cell permeation suppressed CNV via cell surface TLR3 activation. Next, we sought the signaling pathways responsible for this angioinhibitory activity. Mice lacking a functional version of the Trif-adaptor protein, which is used by TLR3 to transduce intracellular signaling,38 were resistant to the antiangiogenic activity of 21-nt siRNAs. Trif activation has been reported to bifurcate either via nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) or interferon-regulatory factor-3 (IRF3)39; we found that 21-nt siRNAs suppressed CNV via activation of NF-κB, but not IRF3.

A survey of the expression profiles of various cytokines led us to determine that interleukin (IL)-12 and interferon (IFN)-γ were upregulated by 21-nt siRNAs after laser injury. We focused on these two cytokines because they are induced by TLR3 activation and suppress angiogenesis in numerous models.40 Our findings that intravitreous administration of IL-12 or IFNγ suppressed laser-induced CNV in B6 wild-type mice, coupled with the resistance of mice lacking the genes encoding for these proteins to the angioinhibitory activity of 21-nt siRNAs, led us to conclude that these cytokines were critical mediators in this process.

Interestingly, we found that 21-nt or longer siRNAs suppressed CNV but shorter versions did not. To understand the structural basis of the inactivity of 19-nt and shorter siRNAs in this model system, we turned to molecular modeling. Using the reported crystal structures of the TLR3 ectodomain and of dsRNA, we found that the minimum length of dsRNA required to span the dimerizing domains of TLR3 corresponded to the end-to-end length of a 21-nt dsRNA. Since TLR3 dimerization is necessary for receptor-mediated signaling,41–43 we attributed the sharp demarcation in siRNA length for suppressing angiogenesis to the geometry of the TLR3:dsRNA complex. Our speculation was subsequently confirmed by an independent reexamination of the TLR3:dsRNA binding complex.44 Several in vitro studies also have reported that 21-nt siRNAs bind and activate TLR3.45–47

Two independent groups have subsequently confirmed our finding that 21-nt siRNAs can suppress CNV in mice, regardless of their targeting sequence.48,49 These groups have also reported that 21-nt siRNAs generically suppress the expression of VEGF-A, further elucidating their mechanism of action. We and our colleagues have also reported that nontargeted 21-nt siRNAs also suppress angiogenesis in models of corneal suture injury, dermal excisional wounding, and hind limb ischemia.33,50 A recent study also reported that nontargeted 21-nt siRNAs can suppress tumor angiogenesis via TLR3 activation.51 Collectively, the robust and broad antiangiogenic effects of nontargeted 21-nt siRNAs have been demonstrated in multiple organs.

dsRNAs and Geographic Atrophy

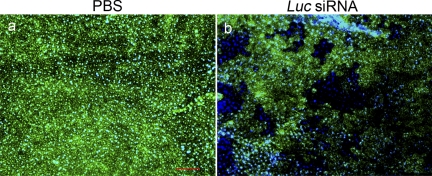

We reported that the poly I:C, a long dsRNA that is a synthetic mimic of viral transcripts, can activate TLR3 and cause retinal pigmented epithelial (RPE) cell death in human RPE cells in culture and in mice in vivo.52 Interestingly, we also found that 21-nt siRNAs can generically cause RPE cell death via TLR3 (Kleinman et al., unpublished data, 2008). Indeed, this generic activity can be misinterpreted as evidence of bona fide target knockdown. For example, intravitreous injection of 21-nt siRNA-Luc causes reduction of GFP signal in GFP transgenic mice because of RPE cytotoxicity (Fig. 2). A similar effect would be observed if 21-nt siRNA-Gfp were administered and could be misconstrued as evidence of gene silencing.

Figure 2.

Intravitreous Luc siRNA administration leads to loss of GFP signal due to retinal degeneration[b]. Transgenic eGFP mice were treated with four intravitreous 21-nt Luc siRNA injections (1 μg). Dramatic retinal cell death and substantially decreased GFP signal were observed with Luc siRNA-treated eyes (b) compared with the PBS controls (a), as seen on RPE/choroid flat mount preparations. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Stimulated by these findings that synthetic dsRNAs can cause RPE cell death, we explored the possibility that endogenous accumulation of dsRNAs may underlie the pathogenesis of geographic atrophy, which is characterized by RPE cell death. Indeed, we found that there was abundant and specific accumulation of dsRNA in the RPE in human donor eyes with geographic atrophy. Unbiased dsRNA sequencing revealed these transcripts to be the Alu RNA that accumulates in the RPE because of a dramatic reduction in the enzyme DICER1 in this disease state.53 Interestingly, the geographic atrophy phenotype in a mouse model of conditional DICER1 ablation was not due to microRNA expression deficits but rather to the accumulation of toxic Alu-like repeat transcripts that activated caspase-3-induced apoptosis.

Concluding Thoughts

Our surprising findings reinforce the need for extraordinary rigor in siRNA experimentation using, for example, the benchmark standards for siRNA experimentation advanced by the Horizon Symposium on RNA54 and other colloquia.55 Our observations also highlight unexpected functions for dsRNAs in modulating cell survival and vascular growth that can be exploited for therapeutic benefit in both atrophic and neovascular AMD.

Acknowledgments

I am profoundly grateful to my many mentors including Anthony Adamis, Donald D'Amico, George Bresnick, the late M. Judah Folkman, Evangelos Gragoudas, Matthew LaVail, Joan Miller, and James Rosenbaum. I have been blessed with numerous outstanding fellows and students in my group, as well as collaborators worldwide, most notably my brother Balamurali Ambati. I also thank for their constant support my parents Ambati M. Rao and Gomathi S. Rao, my wife Kameshwari, and my daughters Meena and Divya.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director, the National Eye Institute, an unrestricted departmental grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB), an RPB Senior Scientific Investigator Award, an RPB Lew R. Wasserman Merit Award, an RPB Physician Scientist Award, the Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scientist Award, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research, the Dr. E. Vernon Smith and Eloise C. Smith Macular Degeneration Endowed Chair, the American Health Assistance Foundation, the International Retinal Research Foundation, the Macula Vision Research Foundation, the E. Matilda Ziegler Foundation for the Blind, the the Jahnigen Career Development Award, and a University of Kentucky Physician Scientist Award.

Disclosure: J. Ambati, P

References

- 1. Kawasaki R, Yasuda M, Song SJ, et al. The prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:921–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krishnan T, Ravindran RD, Murthy GV, et al. Prevalence of early and late age-related macular degeneration in India: the INDEYE study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:701–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Zhang X, Honeycutt AA, Lesesne SB, Saaddine J. Forecasting age-related macular degeneration through the year 2050: the potential impact of new treatments. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:533–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith W, Assink J, Klein R, et al. Risk factors for age-related macular degeneration: pooled findings from three continents. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:697–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilmo A, Prince M. World Alzheimer Report 2010. London: Alzheimer's Disease International; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization World Cancer Report 2008. In: Boyle P, Levin B. eds. Lyon: WHO; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Klein R, Klein BE, Jensen SC, Meuer SM. The five-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:7–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosner B, Colditz GA, Iglehart JD, Hankinson SE. Risk prediction models with incomplete data with application to prediction of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer: prospective data from the Nurses' Health Study. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Photodynamic therapy of subfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration with verteporfin: one-year results of 2 randomized clinical trials—TAP report. Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration with Photodynamic Therapy (TAP) Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:1329–1345 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gragoudas ES, Adamis AP, Cunningham ET, Jr, Feinsod M, Guyer DR. Pegaptanib for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2805–2816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brown DM, Kaiser PK, Michels M, et al. Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1432–1444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenfeld PJ, Brown DM, Heier JS, et al. Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1419–1431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tufail A, Patel PJ, Egan C, et al. Bevacizumab for neovascular age related macular degeneration (ABC Trial): multicentre randomised double masked study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chiu YL, Ali A, Chu CY, Cao H, Rana TM. Visualizing a correlation between siRNA localization, cellular uptake, and RNAi in living cells. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1165–1175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peer D, Park EJ, Morishita Y, Carman CV, Shimaoka M. Systemic leukocyte-directed siRNA delivery revealing cyclin D1 as an anti-inflammatory target. Science. 2008;319:627–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saleh MC, van Rij RP, Hekele A, et al. The endocytic pathway mediates cell entry of dsRNA to induce RNAi silencing. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:793–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Song E, Zhu P, Lee SK, et al. Antibody mediated in vivo delivery of small interfering RNAs via cell-surface receptors. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:709–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Soutschek J, Akinc A, Bramlage B, et al. Therapeutic silencing of an endogenous gene by systemic administration of modified siRNAs. Nature. 2004;432:173–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zimmermann TS, Lee AC, Akinc A, et al. RNAi-mediated gene silencing in non-human primates. Nature. 2006;441:111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kortylewski M, Swiderski P, Herrmann A, et al. In vivo delivery of siRNA to immune cells by conjugation to a TLR9 agonist enhances antitumor immune responses. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:925–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reich SJ, Fosnot J, Kuroki A, et al. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting VEGF effectively inhibits ocular neovascularization in a mouse model. Mol Vis. 2003;9:210–216 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shen J, Samul R, Silva RL, et al. Suppression of ocular neovascularization with siRNA targeting VEGF receptor 1. Gene Ther. 2006;13:225–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ryan SJ. The development of an experimental model of subretinal neovascularization in disciform macular degeneration. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1979;77:707–745 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ambati J, Ambati BK, Yoo SH, Ianchulev S, Adamis AP. Age-related macular degeneration: etiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic strategies. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48:257–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Elias H. Three-dimensional structure identified from single sections. Science. 1971;174:993–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mouton PR. Principles and Practice of Unbiased Stereology: an Introduction to Bioscientists. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nozaki M, Raisler BJ, Sakurai E, et al. Drusen complement components C3a and C5a promote choroidal neovascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2328–2333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nozaki M, Sakurai E, Raisler BJ, et al. Loss of SPARC-mediated VEGFR-1 suppression after injury reveals a novel antiangiogenic activity of VEGF-A. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:422–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sakurai E, Anand A, Ambati BK, van Rooijen N, Ambati J. Macrophage depletion inhibits experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3578–3585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sakurai E, Taguchi H, Anand A, et al. Targeted disruption of the CD18 or ICAM-1 gene inhibits choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2743–2749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kleinman ME, Yamada K, Takeda A, et al. Sequence- and target-independent angiogenesis suppression by siRNA via TLR3. Nature. 2008;452:591–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takeda A, Baffi JZ, Kleinman ME, et al. CCR3 is a target for age-related macular degeneration diagnosis and therapy. Nature. 2009;460:225–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kelly J, Ali Khan A, Yin J, Ferguson TA, Apte RS. Senescence regulates macrophage activation and angiogenic fate at sites of tissue injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3421–3426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Satofuka S, Ichihara A, Nagai N, et al. (Pro)renin receptor promotes choroidal neovascularization by activating its signal transduction and tissue renin-angiotensin system. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1911–1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, et al. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003;301:640–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jiang Z, Mak TW, Sen G, Li X. Toll-like receptor 3-mediated activation of NF-kappaB and IRF3 diverges at Toll-IL-1 receptor domain-containing adapter inducing IFN-beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3533–3538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Voest EE, Kenyon BM, O'Reilly MS, Truitt G, D'Amato RJ, Folkman J. Inhibition of angiogenesis in vivo by interleukin 12. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:581–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ranjith-Kumar CT, Miller W, Xiong J, et al. Biochemical and functional analyses of the human Toll-like receptor 3 ectodomain. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:7668–7678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bell JK, Askins J, Hall PR, Davies DR, Segal DM. The dsRNA binding site of human Toll-like receptor 3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8792–8797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Choe J, Kelker MS, Wilson IA. Crystal structure of human toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) ectodomain. Science. 2005;309:581–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pirher N, Ivicak K, Pohar J, Bencina M, Jerala R. A second binding site for double-stranded RNA in TLR3 and consequences for interferon activation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:761–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kariko K, Bhuyan P, Capodici J, et al. Exogenous siRNA mediates sequence-independent gene suppression by signaling through toll-like receptor 3. Cells Tissues Organs. 2004;177:132–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kariko K, Bhuyan P, Capodici J, Weissman D. Small interfering RNAs mediate sequence-independent gene suppression and induce immune activation by signaling through toll-like receptor 3. J Immunol. 2004;172:6545–6549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Engle X, Scarlett UK, et al. Polyethylenimine-based siRNA nanocomplexes reprogram tumor-associated dendritic cells via TLR5 to elicit therapeutic antitumor immunity. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2231–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ashikari M, Tokoro M, Itaya M, Nozaki M, Ogura Y. Suppression of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization by nontargeted siRNA. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3820–3824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gu L, Chen H, Tuo J, Gao X, Chen L. Inhibition of experimental choroidal neovascularization in mice by anti-VEGFA/VEGFR2 or non-specific siRNA. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:433–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cho WG, Albuquerque RJ, Kleinman ME, et al. Small interfering RNA-induced TLR3 activation inhibits blood and lymphatic vessel growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7137–7142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Berge M, Bonnin P, Sulpice E, et al. Small interfering RNAs induce target-independent inhibition of tumor growth and vasculature remodeling in a mouse model of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:3192–3201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yang Z, Stratton C, Francis PJ, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 and geographic atrophy in age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1456–1463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kaneko H, Dridi S, Tarallo V, et al. DICER1 deficit induces Alu RNA toxicity in age-related macular degeneration. Nature. 2011;471:325–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Whither RNAi (editorial)? Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:489–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Smith C. Sharpening the tools of RNA interference. Nat Methods. 2006;3:475–486 [Google Scholar]