Abstract

Aims: To evaluate sociodemographic correlates associated with transitions from alcohol use to disorders and remission in a Brazilian population. Methods: Data are from a probabilistic, multi-stage clustered sample of adult household residents in the São Paulo Metropolitan Area. Alcohol use, regular use (at least 12 drinks/year), DSM-IV abuse and dependence and remission from alcohol use disorders (AUDs) were assessed with the World Mental Health version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Age of onset (AOO) distributions of the cumulative lifetime probability of each alcohol use stage were prepared with data obtained from 5037 subjects. Correlates of transitions were obtained from a subsample of 2942 respondents, whose time-dependent sociodemographic data were available. Results: Lifetime prevalences were 85.8% for alcohol use, 56.2% for regular use, 10.6% for abuse and 3.6% for dependence; 73.4 and 58.8% of respondents with lifetime abuse and dependence, respectively, had remitted. The number of sociodemographic correlates decreased from alcohol use to disorders. All transitions across alcohol use stages up to abuse were consistently associated with male gender, younger cohorts and lower education. Importantly, low education was a correlate for developing AUD and not remitting from dependence. Early AOO of first alcohol use was associated with the transition of regular use to abuse. Conclusion: The present study demonstrates that specific correlates differently contribute throughout alcohol use trajectory in a Brazilian population. It also reinforces the need of preventive programs focused on early initiation of alcohol use and high-risk individuals, in order to minimize the progression to dependence and improve remission from AUD.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol is one of the leading causes of global burden of disease, particularly in the Americas, European and Western Pacific Regions, where alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are ranked among the first six causes of disability (WHO, 2008). In the Americas, alcohol consumption has been estimated to be 50% greater than the global average (Rehm and Monteiro, 2005) and causes a significant burden in Brazil, the largest country in Latin America. In 2004, the percentage of all disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) attributable to alcohol in Brazilian men (17.7%) was the second greatest among 10 other populous countries, being only lower than Russian men (28.1%). Likewise, Brazilian women displayed a relevant rate of alcohol-attributable DALYs (3.4%), only lower than women from the USA (4.5%) and Russia (10.7%) (Rehm et al., 2009).

Several national and regional Brazilian surveys have investigated the prevalence of alcohol use, AUD and associated sociodemographic correlates. Overall, these studies consistently demonstrated that men consumed more alcohol than women at all ages and were more prone to AUD (Laranjeira et al., 2010; Pechansky et al., 2004). Age group was an important determinant of alcohol use and AUD, which were more prevalent among young adults, whereas marital status displayed different effects across gender (Almeida-Filho et al., 2004; Laranjeira et al., 2010; Silveira et al., 2007). Additionally, various studies in Brazil have demonstrated a negative association between socio-economic status (SES) and AUD (Barros et al., 2007; Mendoza-Sassi and Beria, 2003; Primo and Stein, 2004). However, all of them have focused on correlates for AUD through a static point of view.

Research has shown that alcohol use starts early in life in Brazil (Galduroz et al., 2005; Laranjeira et al., 2007), but the role of age of first use in predicting problematic drinking and AUD was not examined, even though this has been show in literature (Hingson et al., 2006; Pitkanen et al., 2005; Zucker, 2008). Also, the long multi-stage process involved in the pathway from first alcohol use to AUD (Wagner and Anthony, 2002) or developmental stage-specific factors (Sartor et al., 2007) are rarely considered.

Two population-based studies performed in China and USA showed a decreasing number of sociodemographic correlates associated with the transitions throughout alcohol use progression (Kalaydjian et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2009a), with different correlates operating during the first stages of alcohol use and few remaining in transitions towards AUD. These studies are supported by other reports (Poelen et al., 2008; Sartor et al., 2009; van der Zwaluw and Engels, 2009), including two population-based longitudinal twin surveys showing that shared environmental factors diminished across alcohol use stages, whereas genetic factors increased in importance once initiation had occurred (Dick et al., 2007; Pagan et al., 2006).

In this context, the present report, based on data from a population-based study of adults residents in the São Paulo Metropolitan Area (SPMA), aims to evaluate the contribution of age of onset (AOO) of each stage of alcohol use and sociodemographic factors in predicting the transitions across the full trajectory of alcohol use, related disorders and remission in a Brazilian population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data are from the ‘São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey’ (SPMHS) (Viana et al., 2009), the Brazilian counterpart of the World Mental Health Survey (WMHS) Initiative, which has been carried out in several countries with equal sampling procedures and instruments (Degenhardt et al., 2008; Kalaydjian et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2009a).

Participants

A probabilistic sample of household residents aged 18 years and over was assessed in the SPMA (38 municipalities plus the city of São Paulo). Respondents were selected from a stratified multi-stage clustered area probability sample of households, being one respondent per dwelling selected by a Kish selection table. In all strata, the primary sampling units (PSUs) were 2000 census count areas, which were geographically defined and updated by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE, 2001). The city of São Paulo contributed to 40% of the total sample and the remaining municipalities were self-representatives, contributing to the total sample size in proportion to their demographic density.

Data acquisition occurred between May 2005 and April 2007, with face-to-face interviews conducted by trained lay interviewers. A total of 5037 respondents were assessed (response rate of 81.3%).

The interview is composed of clinical and non-clinical sections and is divided into Parts I and II. The first one includes the core mental disorders diagnostic assessment (anxiety, mood, alcohol and substance use disorders and impulse control disorders) and was administered to all respondents (n = 5037). Part II of the interview comprises non-clinical modules (one of them providing information on time-dependent sociodemographic covariates) and non-core clinical sections. Part II was applied to those who met lifetime diagnostic criteria for any of the core disorders assessed in Part I plus a 25% random sample of non-cases, totaling 2942 respondents (Part II sample).

Weights were used to adjust for within household and PSU probability of selection, and for age and gender structure of the SPMA population. Part II respondents were weighted by the inverse of their probability of selection to adjust for differential sampling (see Viana et al., 2009 for details). AOO distributions of cumulative lifetime probability of alcohol use, regular use, abuse and dependence were prepared with the data obtained from 5037 subjects. Correlates of transition from lifetime use to dependence were performed in the Part II sample, whose time-dependent information of sociodemographic status was available. All participants signed a written informed consent prior to the interview, and all procedures were approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, University of São Paulo (Project number 792/03).

Measurements

Diagnostic assessment and alcohol measures

The WMH version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-3.0) (Kessler and Ustun, 2004), translated and adapted to the Brazilian–Portuguese language according to WHO protocol (Viana et al., 2009), was used to assess psychopathology. DSM-IV criteria psychiatric diagnoses were considered herein. The alcohol module, administered to all respondents, consisted in an initial question about the age of first alcohol use (ever use); for those reporting ever use, subsequent questions assessed drinking patterns, problems and remission. In this report, six stages of alcohol use were evaluated: never use, ever use, regular use (ever drinking at least 12 drinks in 12 months), abuse, dependence and remission. The ‘ungated’ approach was used, which means that both abuse and dependence items were independently assessed for all lifetime alcohol users.

AOO and transition variables

In contrast to previous Brazilian studies, this data set provides information on the AOO of several stages of alcohol use, and time-dependent education, student status and marital status, allowing the verification of how AOO of each stage may influence the transition to more severe stages.

The AOO variables created and their respective questions were: AOO of alcohol use (‘How old were you the very first time you ever drank an alcoholic beverage?’); AOO of regular drinking (‘How old were you when you first started drinking at least 12 drinks in a 12-month period?’); AOO of alcohol abuse and dependence, which were defined as the ages at which any symptoms of abuse or dependence first occurred (‘How old were you the very first time you had any of these problems?’ using a list of symptoms related to alcohol abuse and dependence). The AOO of AUD was assigned only to respondents with diagnosis of abuse or dependence. A fourth AOO variable was determined for remission, defined as the cessation of alcohol use and the absence of any pre-existing abuse or dependence symptoms for at least 1 year before the interview. Among respondents with a history of AUD, the most recent age of having any symptom was assessed with the following question: ‘How old were you the last time you had [this problems/(either/any) of these problems] because of drinking?’.

Additional variables were created to represent the speed of transition between the onset of first use and first regular use among lifetime regular users, and the speed of transition between the onset of first regular use and abuse. Both of these speed-of-transition variables were calculated by taking the AOO of the earlier stage of alcohol use and subtracting it from the AOO of the later stage.

Sociodemographic correlates

Sociodemographic correlates included cohort, gender, education level, student status, and marital status. Cohort was defined by age at interview in categories: 18–34, 35–49, 50–64 and 65 years or more. Student status (student versus non-student) was a separate dichotomous variable asked in a specific question about current occupational status (time-varying). Besides assessing the student status, education level was coded categorically in the following ranges of completed years of education: 0–4 (low); 5–8 (low-average); 9–11 (high-average); 12 or + (high). Marital status was classified as: married or cohabitating, previously married (widowed, separated or divorced) and never married. As it varies with time/age, education was coded as a time-varying predictor by assuming an orderly educational history, with 8 years of education corresponding to being a student up to the age of 14 years; other durations were based on this reference point. Information on education, student status and marital status (ever married, age of first marriage and age marriage ended) was included as time-varying covariates in the survival equations for the predictors of transitions. Since time-varying variables were assessed just in Part II sample, all transition models were performed in this subsample.

Statistical analysis

Analysis with time-dependent covariates (conditional probabilities and sociodemographic predictors of transitions) were performed using Part II sample (n = 2942). AOO distributions of the cumulative lifetime probability of alcohol use, regular use, abuse and dependence were prepared with data obtained from Part I sample.

Conditional probabilities of transition across the six stages of alcohol use were determined by cross-tabulation analysis. Estimated projected AOO distributions of the cumulative lifetime probability of alcohol use, regular use, abuse and dependence as of age 60 were obtained by the actuarial method implemented in PROC LIFETEST in SAS (version 9.1.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), which permits the modeling of transitions to subsequent stages of alcohol use while accounting for those individuals who may not have passed through the period of risk (right-censoring).

Predictors of transitions were examined using discrete-time survival analysis using the logit function with person-year as the unit of analysis (Efron, 1988). The use of discrete-time survival curves offers a clearer graphical depiction than previous Brazilian studies regarding the patterns of onset of initiation of alcohol use, regular use and AUDs. Standard errors and significant tests were estimated using the Taylor series linearization method (Wolter, 1985) implemented in SUDAAN to adjust for design effects (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA). Multivariate significance tests were made with Wald χ2 tests using Taylor series design-based coefficient variance-covariance matrices. The person-year data array used in the transition from never use to first use includes all years in the life of respondents before and including their age at first drink. The person-year data array for the following three stages of analysis (ever use to regular use, regular use to abuse and abuse to dependence) included all years beginning with the year after the earlier transition and continuing through the year of onset of the next transition or, for respondents who never made the following transition, through their age at interview. For the transition from abuse or dependence to remission, the person-year data array was defined as all years beginning in the year after the first onset of abuse (in the case of lifetime abusers who never developed dependence) or dependence and continuing either for 1 year after recency (last occurrence) of any abuse/dependence symptom, or until age at interview (in case of respondents whose most recent abuse/dependence symptoms occurred more recently than 1 year before interview, who were defined as not remitted).

All survival equations included predictors for age at interview, gender, education (time-varying), student status (time-varying), marital status (time-varying) and person-year (time-varying). Whenever a change in a time-varying category occurred in the same year of a transition across alcohol use stages, the event considered in the survival analyses was the most recent one in that year. For example, if the subject got married in the same year of a transition, the transition was attributed positively toward the married category (not to the marital status before the transition). The equations for later stages included additional covariates on the onset and timing of earlier stages. For instance, analysis of the transition from regular use to abuse includes predictors for AOO of first use, AOO of regular use and the speed of transition between first use and first regular use. However, any two of the latter three variables perfectly define the third, making it impossible to include all three in any one prediction equation. This problem was addressed by estimating a series of three equations, each with two of these three variables as predictors, and the most parsimonious model was elected. This same process was applied in all equations that included information about multiple earlier transitions. Confidence intervals (CIs) of the odds ratios (ORs) were estimated using the Taylor series method. Multivariate significances were based on Wald χ2 tests. Statistical significance was based on two-sided tests evaluated at the 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Alcohol use, related disorders and remission: lifetime prevalences and probabilities of transitions

The vast majority (85.8%, SE = 1.1) of Part II sample (n = 2942) reported that they had drunk at least one dose of alcohol in their life; 56.2% (SE = 1.2) reported regular use (at least 12 doses in 12 months) at some time in their life; 10.6% (SE = 0.8) and 3.6% (SE = 0.4) met criteria for, respectively, alcohol abuse and dependence at some time in their life.

The transition probabilities, from one stage to another, were computed by dividing each pair of these prevalences, with 65.5% (SE = 1.2) of alcohol users progressing to regular use, 18.8% (SE = 1.3) of regular users developing alcohol abuse and 34.1% (SE = 2.8) of lifetime abusers becoming dependents. Among lifetime abusers, 73.4% remitted in the year before the interview, and 58.8% of the respondents with a history of lifetime alcohol dependence remitted in the previous year.

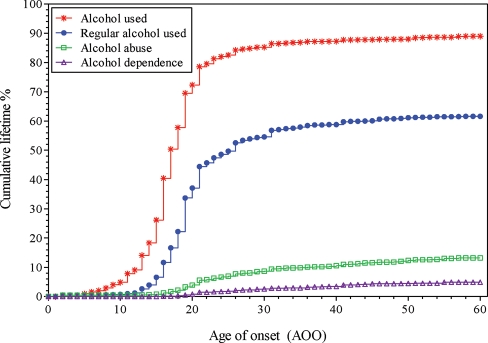

AOO of alcohol use, regular use, abuse and dependence

Figure 1 shows the cumulative AOO curves for first use, regular use, abuse and dependence. For most of the respondents of Part I sample, first alcohol use occurred in the decade between middle adolescence and 26 years of age, with about half of all projected lifetime users initiating use at the age of 17 years old. For alcohol regular use, the sharpest increase occurred between 15 and 20 years of age with the median AOO at 25–26 years. More than half of all projected lifetime alcohol abusers met criteria for this disorder before 24 years of age, whereas ∼60% of first occurrence of lifetime dependence symptoms took place before the age of 35 years.

Fig. 1.

AOO of alcohol use, regular use, abuse and dependence of each user in the total sample (n = 5037).

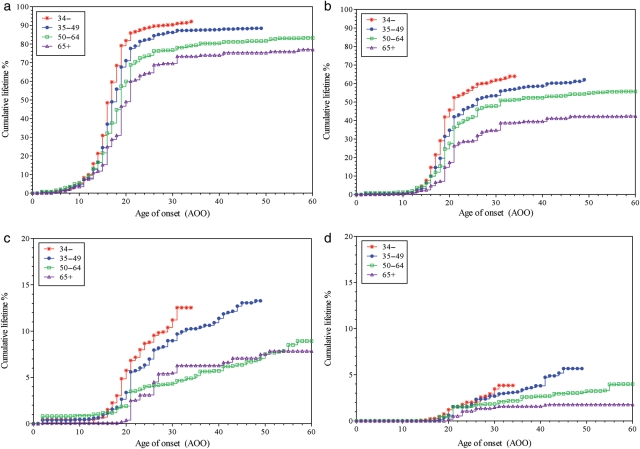

Age effects

Figure 2 shows the cumulative AOO curves for each stage of alcohol use by cohort. Lifetime alcohol use and regular use were more common in younger than older respondents. For instance, 92.1% of the youngest group (18–34 years) had ever used alcohol, compared with 77% of the oldest group (65+ years); however, the median AOO of first use (17–18 years) did not differ across cohorts (Fig. 2a). The lifetime prevalence of regular use among drinkers was 63.9% in the youngest cohort, in contrast to 42.4% in the oldest one, with a slight decrease in the median AOO of regular use between the two more recent cohorts compared with the two older ones (respective medians: 18–19 versus 20–21 years) (Fig. 2b). Lifetime prevalence of alcohol abuse was greater in younger cohorts (∼13%) than in the older ones (∼8%; Fig. 2c). Conversely, the lifetime prevalence for alcohol dependence was greater within the 35–49 cohort (5.7%), followed by the groups of 50–64 (4.0%), 18–34 (3.9%) and 65+ years (1.8%) (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

AOO of (a) first alcohol use, (b) regular use, (c) abuse and (d) dependence of each user in total sample (n = 5037) by cohort.

Sociodemographic predictors of transitions across alcohol use stages

Table 1 presents the results from discrete-time survival analyses, in which AOO was entered as continuous variables, for sociodemographic correlates associated with transitions across alcohol use stages. The number of associations between sociodemographic characteristics and each transition decreased from alcohol ever use to dependence. All transitions were mostly common in male and those between 18 and 34 years old, except for the transition from abuse to dependence. Education level up to high average was associated with all transitions up to abuse, except for low education, which was not associated with regular use among ever users, but was the only correlate of alcohol dependence among abusers. Never married was associated with ever use and regular use among ever users, whereas previously married was associated with regular use among ever users and abuse among regular users.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic correlates associated with transitions across alcohol use stages

| Ever-use among Part II sample (n = 2942) |

Regular use among ever users (n = 2559) |

Abuse among regular users (n = 1738) |

Dependence among abusers (n = 476) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | Sociodemographic category | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) |

| Age (years) | 18–34 | 3.86* | (2.64–5.64) | 1.58* | (1.13–2.20) | 1.98* | (1.02–3.85) | 2.26 | (0.77–6.60) |

| 35–49 | 2.68* | (1.81–3.99) | 1.40* | (1.05–1.85) | 1.49 | (0.86–2.59) | 1.89 | (0.74–4.84) | |

| 50–64 | 1.85* | (1.08–3.16) | 1.30 | (0.93–1.82) | 0.87 | (0.48–1.58) | 1.41 | (0.42–4.74) | |

| 65+ | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| Gender | Female | 0.57* | (0.49–0.65) | 0.41* | (0.34–0.51) | 0.53* | (0.38–0.75) | 0.78 | (0.50–1.23) |

| Male | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| Student status | Student | 1.06 | (0.48–2.35) | 1.02 | (0.63–1.65) | 3.50* | (1.51–8.12) | 0.56 | (0.10-3.09) |

| Non-student | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| Education level | Low | 2.33* | (1.03–5.31) | 1.34 | (0.91–1.96) | 3.35* | (1.44–7.78) | 6.13* | (1.28–29.26) |

| Low-average | 3.53* | (1.62–7.72) | 1.54* | (0.98–2.39) | 3.52* | (1.42–8.69) | 2.42 | (0.54–10.97) | |

| High-average | 3.96* | (1.52–10.35) | 1.49* | (1.03–2.14) | 2.36* | (1.11–5. 05) | 2.23 | (0.45–11.10) | |

| High | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| Marital status | Never married | 3.14* | (2.15–4.59) | 1.49* | (1.11–1.98) | 1.26 | (0.90–1.75) | 1.59 | (0.85–2.97) |

| Previously married | 0.30* | (0.19–0.48) | 1.58* | (1.10–2.26) | 2.00* | (1.35–2.96) | 1.01 | (0.53–1.93) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| AOO | of first alcohol use | – | – | 1.01 | (0.99–1.03) | 0.90* | (0.87–0.94) | – | – |

| of regular alcohol use | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.94 | (0.89–1.01) | |

Results are based on multivariate discrete-time survival model with person-year as the unit of analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*Significant OR (P < 0.05, two-sided test).

First alcohol use was positively associated with age under 65 years, male, with low to high-average education level and never married, but negatively associated with being previously married. Regular alcohol use among ever users was associated with age under 50 years, male, high-average education level, never or previously married. The correlates for alcohol abuse among regular users were: age between 18 and 34 years, male, being student, up to high-average education level and previously married. The age of first alcohol use was inversely related to the transition from regular use to abuse, which means that the earlier the AOO of first use, the greater the odds to transit from regular use to abuse. Noticeably, being a student was a risk factor only for the transition from regular use to abuse. In contrast to the other transitions, cohort and gender associations were no longer observed for the transition to alcohol dependence, for which the only predictor was low education level.

Sociodemographic predictors of remission from alcohol abuse and dependence

Table 2 presents the results from discrete-time survival analyses, in which AOO was entered as continuous variables, for sociodemographic associations of remission from AUD. Remission from either alcohol abuse or dependence was associated with older AOO of abuse. Remission from alcohol abuse was more common among young and middle-aged abusers (18–49 years old), whereas remission from alcohol dependence was less common among dependents with low education level.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic correlates associated with remission from alcohol abuse and dependence

| Remission from alcohol abuse (n = 349) |

Remission from alcohol dependence (n = 104) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | Sociodemographic category | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) |

| Age (years) | 18–34 | 18.20* | (3.99–83.02) | 1.93 | (0.58–6.44) |

| 35–49 | 5.28* | (1.53–18.24) | 1.72 | (0.59–4.98) | |

| 50–64 | 1.91 | (0.75–4.82) | 1.28 | (0.65–2.50) | |

| 65+ | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| Gender | Female | 1.11 | (0.59–2.06) | 1.20 | (0.55–2.63) |

| Male | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| Student status | Student | 0.38 | (0.10–1.48) | 0.15 | (0.02–1.40) |

| Non-student | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| Education level | Low | 0.93 | (0.50–1.74) | 0.35* | (0.18–0.67) |

| Low-average | 1.17 | (0.68–2.04) | 0.65 | (0.27–1.53) | |

| High-average | 0.91 | (0.56–1.50) | 0.69 | (0.34–1.40) | |

| High | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| Marital status | Never married | 1.41 | (0.80–2.47) | 0.83 | (0.45–1.54) |

| Previously married | 1.26 | (0.77–2.07) | 1.31 | (0.59–2.89) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | |

| AOO | of alcohol abuse | 1.11* | (1.07–1.16) | 1.05* | (1.01–1.08) |

Results are based on multivariate discrete-time survival model with person-year as the unit of analysis. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

*Significant OR (P < 0.05, two-sided test).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to investigate the AOO of the different stages of alcohol use and remission from AUD, and to verify influences of gender, age and time-dependent education level and marital status on the transitions across the full trajectory of alcohol use in a large Brazilian population-based sample.

The lifetime rates of alcohol use and regular use observed herein reflect a considerable exposure to alcohol and its continuous use in a significant proportion of this urban population, in agreement with the previous reports (Degenhardt et al., 2008; Galduroz and Carlini, 2007; Laranjeira et al., 2010). Additionally, ∼10 and 3.6% of the sample in São Paulo met lifetime criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence, respectively, consistent with other countries with no strong cultural and/or regulatory restrictions to alcohol use (Bromet et al., 2005; Wells et al., 2007).

In our study, male gender, younger cohorts and lower education levels were consistently associated with transitions up to abuse. Abuse among regular users was also associated with early age of first use. Nonetheless, most of the correlates were no longer associated with the transition from alcohol abuse to dependence; only low education level was strongly associated with this transition. These demonstrate that the number of sociodemographic correlates associated with the transitions across alcohol use stages decreased throughout alcohol use progression, which supports the results from other WMHS reports (Kalaydjian et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2009a). Likewise, all transitions up to abuse were more likely to occur among men than women, and among the youngest cohorts. The gender differences in alcohol consumption (mainly in the first stages) have been usually explained by the differences in innate physiological and psychosocial factors (Devaud and Prendergast, 2009; Kerr-Correa et al., 2007). In parallel, the young have been reported to be at highest risk for alcohol use and to consume greater amounts than other cohorts (Ahlström and Österberg, 2004/2005; Galduroz and Carlini, 2007; Laranjeira et al., 2010). Indeed, in the present study, age between 18 and 34 years was associated with most of the transitions analyzed, but not with the transition from alcohol abuse to dependence, similarly to reports from USA and China (Kalaydjian et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2009a). Overall, individuals with lower education level were more likely to experience first alcohol use and transit towards regular use and abuse, and were less likely to remit from alcohol dependence in São Paulo and USA, whereas education level was not a predictor for any of the transitions in China. Conversely, student status presented different associations among studies, reflecting the influence of cultural and economic factors on alcohol use, as discussed later in this section.

The importance of low education remaining as a strong predictor of the transition from abuse to dependence was further emphasized by the fact that it was also the only correlate negatively associated with remission from alcohol dependence. Different explanations are plausible: (i) less education could implicate in less access to information and AUD treatment; (ii) as shown for substance use (Lee et al., 2009b), alcohol use could be associated with early termination of education and (iii) since education level is widely used as an indicator of SES (Bloomfield et al., 2006), our results may reflect the high exposure to alcohol of individuals with lower SES, either by living in a region with a high concentration of bars and liquor stores or by less restricted community norms about alcohol use (Crum et al., 1993). Moreover, individuals who drop out of school or do not achieve their educational goals may be at increased risk for AUD by using alcohol as a coping mechanism (Zucker, 2008).

Student status was only associated with the transition from regular use to alcohol abuse in São Paulo, while it was associated with all stages of alcohol use in the USA, where college drinking is a major public health problem (Hingson et al., 2009). In contrast, in China, where alcohol use in school is strongly restricted, being a student was a protective factor for the transition from alcohol use to regular use and was more likely to remit from AUD (Lee et al., 2009a). The Brazilian drinking culture is characterized by high alcohol intake per occasion, drinking in public places and not drinking with meals (Rehm and Monteiro, 2005). This is particularly alarming among students, who are highly exposed to alcohol in different ways: (i) there is no legal minimum drinking age, and the only restriction in this matter, scarcely enforced, is not to sell alcohol to persons <18 years old; (ii) no special license is required to sell alcohol and (iii) usually, there is no specific restriction on alcohol use or sale inside the University campus. This scenario is reflected in studies showing that 10–20% of the students have at least one episode of binge drinking (five or more drinks in a single occasion) in the past month (Galduroz et al., 2010; Vieira et al., 2007) and an increased trend in college drinking (Stempliuk et al., 2005), which emphasizes the need for prevention programs focusing this population.

Interestingly, being previously married was negatively associated with the transition from never use to first alcohol use, but positively associated with the transitions from ever use to regular use and from regular use to abuse. This was also observed in the USA (Kalaydjian et al., 2009), while in China only the first association was reported (Lee et al., 2009a). The finding that marital disruption does not lead to first alcohol exposure is rather difficult to contextualize due to the lack of research regarding this association. Conversely, it is well established that alcohol use is reduced by the transition to marriage, heavy drinking affects marital quality and stability, and marriage disruption increases alcohol consumption, heavy drinking and related problems (Dawson et al., 2005a; Leonard and Eiden, 2007; Silveira et al., 2007; Scott et al., 2009).

In our study, about half of all lifetime users initiated alcohol use at 17 years old, and a clear cohort effect was not found for AOO of first alcohol use, differently from previous studies in Brazil (Galduroz et al., 2005; Laranjeira et al., 2007; Vieira et al., 2007). However, none of these studies assessed AOOs as time-dependent variables, what could bring the mean age of first drinking artificially to an early age.

The present study showed the association between early AOO of first alcohol use and the transition from regular use to abuse. Similar result was reported in USA, where also early AOO of regular use was associated with the transition from abuse to dependence (Kalaydjian et al., 2009). This last association was not found in São Paulo possibly due to the later median AOO of regular use (25–26 years of age) consistent with studies in which starting to drink later was associated with developing alcohol dependence at an older age (Dawson et al., 2008; Hingson et al., 2006). Early drinking has been considered a manifestation of a general vulnerability to high risk-taking behaviors (Prescott and Kendler, 1999; Zucker, 2008), being a non-specific/non-causal marker of elevated risk for adult alcohol-related problems and AUD. Nevertheless, because this association persists even after controlling for family history of alcoholism, behavioral and personality characteristics, early exposure to alcohol might increase its misuse due to alcohol effects on the developing brain (Hingson et al., 2006; Pitkanen et al., 2005).

Remission from AUD in São Paulo was associated with a later AOO of alcohol abuse, which is in agreement with WMHS reports. Considering early AOO of AUD as a marker of disorder severity, a later AOO of alcohol abuse would increase the chance of remission (Kalaydjian et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2009a). Moreover, remission from abuse was strongly correlated with younger age, as also previously reported (Kalaydjian et al., 2009). Senior alcohol abusers may present more difficulties in remitting possibly due to the progression of the disorder with increased severity. Importantly, there is no complete accurate global term for the discontinuation of alcohol use among individuals that previously met criteria for AUD. There are variations among the studies regarding the extent and type of remission (non-abstinent, abstinent, early, partial and full), which lead to different remission rates and correlates (Dawson et al., 2005b). Nevertheless, some correlates of remission from AUD have been consistently reported elsewhere and in the present study: later AOO of alcohol abuse (Bischof et al., 2001; Dawson, 1996) and education (Dawson, 1996; Schutte et al., 2003).

Some limitations of the study are worth mentioning. First, although these data were collected from a highly heterogeneous population in Southeast Brazil, our findings cannot be generalized to other Brazilian regions. Second, other correlates as income and social deprivation could also be implicated in the transitions across alcohol use stages, and this should be included in future analyses. Third, the retrospective estimates of AOO may be biased because respondents tend to report experiences closer to the interview, even though information was given to distinguish AOO for each stage. The reliability and validity of highly retrospective self-reports regarding lifetime drinking history have been shown (Koenig et al., 2009), with no indication that rank ordering for different events is affected, at least for tobacco use (Johnson and Schultz, 2005). To deal with the autobiographical memory limits, there were special probes for respondents who could not recall the exact age of a given experience. For example, one probe was ‘was it before your twenties?’ if the respondent answered ‘yes’, the upper end of the range (20 years of age) was used in analysis to give a consistently conservative, lower-bound estimate (Kessler and Ustun, 2004).

Finally, in theory, it is possible to study three forms of transitions in AUD: (i) ‘concurrent onsets of abuse and dependence’, when the first DSM-IV non-dependent alcohol abuse (NDAA) occurs for the first time during the same year of life as the first DSM-IV alcohol dependence problem; (ii) ‘dependence before abuse’, when the first dependence problem predates the first NDAA problem and (iii) ‘abuse before dependence’, when the first NDAA problem predates the first dependence problem. To explore all of them, questions regarding the AOO of the first NDAA problem and the AOO of the first alcohol dependence problem were compared. In the present study, there were too few examples of the first two forms (∼15% of the positive cases for both AUD had concurrent onsets of abuse and dependence; ∼10% had dependence before abuse). For >75% of the individuals who qualified for both AUD, the AOO value for the first NDAA problem predated the subject's separately assessed AOO value for the first experienced dependence problem. This allowed the transition analyses for the third form (abuse before dependence); but not for the other two due to the few cases. As previously reported, the transition from first alcohol use directly to dependence or to AUD (abuse and dependence, without imposing the DSM-IV hierarchy of these disorders) is an interesting approach to avoid the issue of dependence occurring before/in the same year of abuse (Behrendt et al., 2008; Dawson et al., 2008), which should be considered in future studies.

Despite these limitations, the SPMHS provided substantial reliable information on the transitions throughout the full trajectory of alcohol use by using an international validated methodology. Moreover, the ‘ungated’ approach used herein avoids the underestimation of dependence rates promoted by the ‘abuse gate approach’ (Degenhardt et al., 2007). In this sense, it further provided estimates of alcohol use, related disorders and remission in the largest Brazilian city.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates in a Brazilian population that qualitatively different correlates may contribute during the different stages of progression of alcohol use and disorders, with each transition being moderated by more than one factor. Possibly, environmental or cultural variables play a greater role in earlier phases of use, whereas transitions to AUD are more influenced by biological factors. In order to reduce early initiation of alcohol use, educational programs in school settings combined with family interventions are indicated (Spoth et al., 2005). For the later transitions, efforts should reach individuals from deprived areas of SPMA. Prospective research is therefore necessary to minimize memory biases and confirm the nature of associations for sociodemographic characteristics across the full trajectory of alcohol use.

Funding

The São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey is supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) Thematic Project Grant 03/00204-3. Instrument development was supported by the Fundo de Apoio à Ciência e Tecnologia do Município de Vitória (FACITEC—Vitoria Foundation for Science and Technology 002/2003), and the sub-project on violence and trauma was supported by the São Paulo State Secretaria de Segurança Pública. The São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. These activities were supported by the United States National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH070884), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864 and R01-DA016558), the Fogarty International Center (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the Pan American Health Organization, the Eli Lilly & Company Foundation, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Shire. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh.

Acknowledgement

We thank the WMH staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork and data analysis.

REFERENCES

- Ahlström SK, Österberg EL. International perspectives on adolescent and young adult drinking. Alcohol Res Health. 28:258–68. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-Filho N, Lessa I, Magalhães L, et al. Alcohol drinking patterns by gender, ethnicity, and social class in Bahia, Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2004;38:45–54. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102004000100007. doi:10.1590/S0034-89102004000100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros MB, Botega NJ, Dalgalarrondo P, Marin-Leon L, de Oliveira HB. Prevalence of alcohol abuse and associated factors in a population-based study. Rev Saude Publica. 2007;41:502–9. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102006005000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt S, Wittchen HU, Hofler M, et al. Risk and speed of transitions to first alcohol dependence symptoms in adolescents: a 10-year longitudinal community study in Germany. Addiction. 2008;103:1638–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02324.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischof G, Rumpf HJ, Hapke U, Meyer C, John U. Factors influencing remission from alcohol dependence without formal help in a representative population sample. Addiction. 2001;96:1327–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.969132712.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.969132712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield K, Grittner U, Kramer S, Gmel G. Social inequalities in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems in the study countries of the EU concerted action ‘Gender, Culture and Alcohol Problems: a Multi-national Study. Alcohol Alcohol Suppl. 2006;41:i26–36. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromet EJ, Gluzman SF, Paniotto VI, et al. Epidemiology of psychiatric and alcohol disorders in Ukraine: findings from the Ukraine World Mental Health survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:681–90. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0927-9. doi:10.1007/s00127-005-0927-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum RM, Helzer JE, Anthony JC. Level of education and alcohol abuse and dependence in adulthood: a further inquiry. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:830–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.6.830. doi:10.2105/AJPH.83.6.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA. Correlates of past-year status among treated and untreated persons with former alcohol dependence: United States, 1992. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:771–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01685.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Ruan WJ. The association between stress and drinking: modifying effects of gender and vulnerability. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005a;40:453–60. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, Grant BF. Age at first drink and the first incidence of adult-onset DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:2149–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00806.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00806.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Huang B, Ruan WJ. Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001-2002. Addiction. 2005b;100:281–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Bohnert KM, Anthony JC. Case ascertainment of alcohol dependence in general population surveys: ‘gated’ versus ‘ungated’ approaches. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16:111–23. doi: 10.1002/mpr.220. doi:10.1002/mpr.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Chiu WT, Sampson N, et al. Toward a global view of alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, and cocaine use: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaud LL, Prendergast MA. Introduction to the special issue of alcohol and alcoholism on sex/gender differences in responses to alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:533–4. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agp046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick DM, Pagan JL, Viken R, et al. Changing environmental influences on substance use across development. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10:315–26. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.2.315. doi:10.1375/twin.10.2.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B. Logistic regression, survival analysis, and the Kaplan-Meier curve. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83:414–25. doi:10.2307/2288857. [Google Scholar]

- Galduroz JC, Carlini EA. Braz J Med Biol Res. Vol. 40. —; 2007. Use of alcohol among the inhabitants of the 107 largest cities in Brazil—2001; pp. 367–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galduroz JC, Noto AR, Fonseca AM, Carlini EA. V Levantamento Nacional Sobre o Consumo de Drogas Psicotrópicas entre Estudantes do Ensino Fundamental e Médio da Rede Pública de Ensiono nas 27 Capitais Brasileiras, 2004. São Paulo, SP, Brazil: CEBRID Centro Brasileiro de Informações Sobre Drogas Psicotrópicas: UNIFESP Universidade Federal de São Paulo; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Galduroz JC, Sanchez ZM, Opaleye ES, et al. Factors associated with heavy alcohol use among students in Brazilian capitals. Rev Saude Publica. 2010;44:267–73. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102010000200006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:739–46. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;(Suppl 16):12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatìstica - IBGE. 2001 Censo demográfico populacional do ano 2000. Available from: http://www.ibge.gov.br/censo/ (15 January 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, Schultz L. Forward telescoping bias in reported age of onset: an example from cigarette smoking. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14:119–29. doi: 10.1002/mpr.2. doi:10.1002/mpr.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaydjian A, Swendsen J, Chiu WT, et al. Sociodemographic predictors of transitions across stages of alcohol use, disorders, and remission in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.012. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr-Correa F, Igami TZ, Hiroce V, Tucci AM. Patterns of alcohol use between genders: a cross-cultural evaluation. J Affect Disord. 2007;102:265–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.031. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. doi:10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig LB, Jacob T, Haber JR. Validity of the lifetime drinking history: a comparison of retrospective and prospective quantity-frequency measures. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70:296–303. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laranjeira R, Pinsky I, Zaleski M, Caetano R. I Levantamento Nacional sobre os padrões de consumo de álcool na população brasileira. Brasília, DF, Brazil: SENAD Secretaria Nacional de Políticas sobre Drogas; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laranjeira R, Pinsky I, Sanches M, Zaleski M, Caetano R. Alcohol use patterns among Brazilian adults. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2010;32:231–41. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462009005000012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Guo WJ, Tsang A, et al. Associations of cohort and socio-demographic correlates with transitions from alcohol use to disorders and remission in metropolitan China. Addiction. 2009a;104:1313–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02595.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Tsang A, Breslau J, et al. Mental disorders and termination of education in high-income and low- and middle-income countries: epidemiological study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009b;194:411–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054841. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:285–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Sassi RA, Beria JU. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders and associated factors: a population-based study using AUDIT in southern Brazil. Addiction. 2003;98:799–804. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00411.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagan JL, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Genetic and environmental influences on stages of alcohol use across adolescence and into young adulthood. Behav Genet. 2006;36:483–97. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9062-y. doi:10.1007/s10519-006-9062-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pechansky F, Genro VK, Von Diemen L, Kessler FH, da Silveira-Santos RA. References to alcohol consumption and alcoholism in medical records of a general hospital of Porto Alegre, Brazil—a comparison between samples with a 20 year gap. Subst Abus. 2004;25:29–34. doi: 10.1300/j465v25n02_05. doi:10.1300/J465v25n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen T, Lyyra AL, Pulkkinen L. Age of onset of drinking and the use of alcohol in adulthood: a follow-up study from age 8-42 for females and males. Addiction. 2005;100:652–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01053.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poelen EA, Derks EM, Engels RC, et al. The relative contribution of genes and environment to alcohol use in early adolescents: are similar factors related to initiation of alcohol use and frequency of drinking? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:975–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00657.x. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott CA, Kendler KS. Age at first drink and risk for alcoholism: a noncausal association. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:101–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primo NLNP, Stein AT. Prevalência do abuso e da dependência de álcool em Rio Grande (RS): um estudo transversal de base populacional. Rev Psiquiatr Rio Gd Sul. 2004;26:280–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Monteiro M. Alcohol consumption and burden of disease in the Americas: implications for alcohol policy. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;18:241–8. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005000900003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:2223–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Heath AC, Jacob T, True W. The role of childhood risk factors in initiation of alcohol use and progression to alcohol dependence. Addiction. 2007;102:216–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01661.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor CE, Lynskey MT, Bucholz KK, Madden PA, Martin NG, Heath AC. Timing of first alcohol use and alcohol dependence: evidence of common genetic influences. Addiction. 2009;104:1512–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02648.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutte KK, Nichols KA, Brennan PL, Moos RH. A ten-year follow-up of older former problem drinkers: risk of relapse and implications of successfully sustained remission. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64:367–74. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM, Wells JE, Angermeyer M, et al. Gender and the relationship between marital status and first onset of mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. Psychol Med. 2009;26:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira CM, Wang YP, Andrade AG, Andrade LH. Heavy episodic drinking in the São Paulo epidemiologic catchment area study in Brazil: gender and sociodemographic correlates. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:18–27. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Randall GK, Shin C, Redmond C. Randomized study of combined universal family and school preventive interventions: patterns of long-term effects on initiation, regular use, and weekly drunkenness. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19:372–81. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.372. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stempliuk VA, Barroso LP, Andrade AG, Nicastri S, Malbergier A. Comparative study of drug use among undergraduate students at the University of São Paulo - São Paulo campus in 1996 and 2001. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2005;27:185–93. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462005000300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwaluw CS, Engels RC. Gene-environment interactions and alcohol use and dependence: current status and future challenges. Addiction. 2009;104:907–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02563.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana MC, Teixeira MG, Beraldi F, Bassani IS, Andrade LH. São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey a population-based epidemiological study of psychiatric morbidity in the São Paulo Metropolitan Area: aims, design and field implementation. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2009;31:375–86. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462009000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira DL, Ribeiro M, Laranjeira R. Evidence of association between early alcohol use and risk of later problems. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2007;29:222–7. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462007000300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner FA, Anthony JC. From first drug use to drug dependence; developmental periods of risk for dependence upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:479–88. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00367-0. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells JE, Baxter J, Schaaf D. Substance Use Disorders in Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Wellington: Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva: World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wolter KM. Introduction to Variance Estimation. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA. Anticipating problem alcohol use developmentally from childhood into middle adulthood: what have we learned? Addiction. 2008;103(((Suppl 1)1):100–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02179.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]