Abstract

Chronic back pain often leads to permanent disability and—apart from significant human suffering—also creates immense economic costs. There have been numerous epidemiological studies focussing on the incidence and the course of chronic low back pain. Less attention has been paid to the impact of subjective perception of the disease and the degree of healthcare use of these patients. The aim of this study was to gather data about patients with chronic low back pain and compare these data with patients suffering from chronic pain in other body regions. The first 300 pain questionnaires collected by the interdisciplinary pain centre at the University Hospital in Freiburg between January 2000 and September 2001 were analysed. This pain questionnaire is a modified version of the pain questionnaire of the DGSS (Deutsche Gesellschaft zum Studium des Schmerzes—German Chapter of the IASP). It collects demographic and socioeconomic information, as well as information regarding the course of the disease, and the subjective description of pain and the pain-related impairment. The subjective view of the course of disease, shows differences between patients with low back pain and patients with chronic pain of other origin, particularly regarding physical strain as the assumed cause of pain, but also regarding the frequency of prior treatments and cures. The subjective perception of the course of the pain disorder in patients with low back pain compared to patients with chronic pain in other parts of the body shows differences mainly related to the capacity for physical exertion. The frequency of ineffective prior treatments and cures underlines the necessity for early initiation of effective pain treatment aimed at prevention of the pain disorder becoming chronic.

Introduction

The incidence of low back pain has been well documented by population studies [1–5]. The prevalence is 30–40% among the adult population, while the annual prevalence exceeds 60% and the lifetime prevalence is 80%. There is a significant tendency toward emergence of a chronic form over the course of the disease [6]. Recent estimates suggest that there are five to eight million patients suffering from chronic pain in the Federal Republic of Germany [7]. Chronic low back pain was the most common complaint after headache. Chronic back pain often leads to permanent disability and—apart from significant human suffering—also creates immense economic costs. Guidelines for the treatment of lower-back pain aiming at prevention of chronic low back pain by identifying patients who will benefit from specific types of treatment have had limited success as they are applied infrequently [8].

A number of individual risk factors interact in a complex way to result in persistence of pain. These include prior pain experiences, physical complaints, sociodemographic factors, lifestyle factors, psychosocial factors and factors relating to the patient’s work environment [6, 9, 10]. Therefore, the goal of this retrospective study was to determine how chronic back pain patients differ in how they subjectively experience the course of their illness in contrast to patients with chronic pain conditions affecting other parts of the body, and thus be able to draw conclusions about the development of chronic back pain. To this end, we used the modified German pain questionnaire and performed an initial epidemiological analysis of 297 patients with chronic pain at our Interdisciplinary Pain Centre at the University Hospital Freiburg.

Patients with chronic low back pain and other chronic pain patients were given special consideration in our study. We identified 126 patients with initial diagnoses of chronic back pain and 171 patients with chronic pain in other locations.

Materials and methods

The survey instrument

The questionnaire used by the Interdisciplinary Pain Centre in Freiburg is based on the German Pain Questionnaire (Deutscher Schmerzfragebogen, DSF) which has been developed and validated by the Task force on "Standardization and Economy in Pain Management" of the German chapter of the International Association for the Study of Pain (DGSS). The concept of the DSF is based on a bio (medical)–psycho–social pain model [11].

In our study, the questions regarding the course of the disease were arranged according to the following criteria, representing a partial modification of the structure of the DSF questionnaire:

Patients’ presumed aetiology of disease (subjective causes, family history, occupational and other accidents)

Comorbidities

Doctor’s visits and treatment (changing primary care physician, number of visits, physicians consulted, treatments, admission to hospital, stays at rehabilitative facilities, and operations for pain as well as for other conditions)

The Freiburg pain questionnaire does not differ from the DSF questionnaire in any way in relation to the questions examined in this study apart from these formal changes.

Methods

Three hundred questionnaires by the Interdisciplinary Pain Centre Freiburg were evaluated. Only 297 persons could be included in the study because the questionnaires were incomplete for three persons. The cohort was made up of patients referred from primary care and other clinics between January 2000 and September 2001 and presented to the Interdisciplinary Pain Centre Freiburg with chronic pain. All patients fulfilled the criteria for chronic pain. The pain questionnaire was completed by the patients themselves immediately prior to their initial presentation.

The following procedure was followed after receiving the questionnaires:

The patient’s name (and maiden name, where applicable) were encoded.

All data were entered into an access database.

The cohort was divided into two groups according to ICD-10. Group A comprised back pain patients (n = 126) and group B, patients with other forms of chronic pain (n = 171). Group B included patients with head and facial pain (n = 67), pain of the neck or extremities (n = 37), visceral pain (n = 19), hip pain and/or lower extremity pain (n = 30) or whole body pain or joint pain (n = 18).

In cases with prolonged episodes or multiple forms of pain, only the current (main) pain at presentation was considered in this study. Selection criteria for group A were those subgroups of the ICD-10 diagnoses M40 through M54 which code for pain of the spine and low back, and information gathered from the patients medical notes. Only patients with low back pain as first and main diagnosis were classified in group A. All other patients were subsumed in group B.

Pain was defined as chronic if it occurred continuously or recurrently over at least six months.

Statistical analysis was performed by the Medical Biometrics and Medical Informatics Institute of the University of Freiburg using SAS software.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, range, standard deviation ) were applied to the findings in both groups. The groups were compared using the following tests: chi-square test (continuity adjusted chi-square for 2 × 2 tables, likelihood-ratio chi-square, Mantel-Haenszel chi-square and Fisher's exact test for 2 × 2 tables), Kruskal-Wallis test (for ordinal scaled variables). A p value < 0.05 indicated significance. Power size estimation suggested a detectable alternative of 16.2% for dichotomous items and 3.3% for independent t-tests with a type I error probability of 0.05 and a power of 0.8.

Results

General and socio-demographic data

No significant difference was found with regard to general data such as gender, age, height, weight, (Table 1) or socio-demographic data such as marital status, religion, level of education or occupational status.

Table 1.

Age, body height and weight, and body mass index (BMI)

| Characteristics | Group A | Group B | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum | N | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Age, years | 126 | 55.6 | 15.9 | 9 | 87 | 170 | 54.1 | 15.7 | 16 | 88 |

| Body height, cm | 123 | 169.3 | 8.8 | 145 | 193 | 170 | 168.6 | 8.2 | 150 | 190 |

| Body weight, kg | 119 | 75.1 | 15.1 | 40 | 155 | 167 | 72.3 | 15.1 | 44 | 110 |

| BMI | 115 | 26.1 | 5.3 | 14 | 63.6 | 160 | 25.2 | 4.2 | 15.9 | 38.8 |

Pain rating

There were no statistically significant differences in the pain rating scores between the two groups of patients (Table 2).

Table 2.

Pain strength on the visual analogue scale (VAS)

| Description | Group A | Group B | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum | N | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Mean pain intensitya | 120 | 7.2 | 1.8 | 3 | 10 | 161 | 7.1 | 1.9 | 0 | 10 |

| Maximal pain intensitya | 118 | 8.6 | 1.3 | 5 | 10 | 163 | 8.6 | 1.4 | 0 | 10 |

| Minimal pain intensitya | 111 | 4.7 | 2.8 | 0 | 10 | 154 | 4.7 | 2.7 | 0 | 10 |

| Actual pain intensityb | 118 | 6.4 | 2.5 | 0 | 10 | 161 | 5.9 | 2.7 | 0 | 10 |

| Bearable pain intensityc | 110 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 0 | 10 | 158 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 0 | 10 |

a Pain intensity during the preceeding four weeks

b Pain intensity at the time of filling in the questionnaire

c Pain intensity considered bearable in case of successful treatment

Duration of pain

The duration of pain was 4.6 years in group A (SD 4.6, min 0.2 years, max 30 years) and 5.7 years in group B (SD 8.1, min 0.2 years, max 44 years). The difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.6568, Mann Whitney test).

Presumed aetiology of disease

Significantly more back pain patients (53.2%) than other pain patients (22.2%) attributed the cause of their pain to physical exertion (p = 0.001). In both groups, generally no other family member suffered from similar pain (82.2% of the back pain and 85.6% of the other pain patients, Table 3). The majority of those surveyed reported that their pain was neither the result of an accident in general (56.5% and 57.1%, respectively) nor the result of an occupational injury (93.1% and 94.6%, respectively). Up to 14% of patients did not respond to this item.

Table 3.

Patients attributions regarding the aetiology of their pain disorder (for presumed aetiology more than one answer were possible)

| Patient attributions of pain | Back pain patients (group A) | Patients with pain in other body areas (group B) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Presumed aetiology | Illness | 39 | 31 | 47 | 27.5 | |

| Surgery | 35 | 27.8 | 56 | 32.7 | ||

| Accident | 16 | 12.7 | 30 | 17.5 | ||

| Physical exertion | 67 | 53.2 | 38 | 22.2 | 0.001 | |

| Psychological stress | 17 | 13.5 | 26 | 15.2 | ||

| Genetic | 3 | 2.4 | 13 | 7.6 | ||

| Other | 10 | 7.9 | 21 | 12.3 | ||

| Unknown | 22 | 17.5 | 37 | 21.6 | ||

| No response | 4 | 3.1 | 7 | 4 | ||

| Positive family history | yes | 21 | 17.8 | 24 | 14.4 | |

| No | 97 | 82.2 | 143 | 85.6 | 0.4 | |

| Total | 118 | 100 | 167 | 100 | ||

| No response | 8 | 6.7 | 4 | 2.3 | ||

| Other accidents | Yes | 50 | 43.5 | 69 | 42.9 | |

| No | 65 | 56.5 | 92 | 57.1 | 0.1 | |

| Total | 115 | 100 | 161 | 100 | ||

| No response | 11 | 8.7 | 10 | 5.8 | ||

| Occupational accidents | Yes | 8 | 6.9 | 8 | 5.4 | |

| No | 108 | 93.1 | 139 | 94.6 | 0.9 | |

| Total | 116 | 100 | 147 | 100 | ||

| No response | 10 | 7.9 | 24 | 14 | ||

Comorbidities

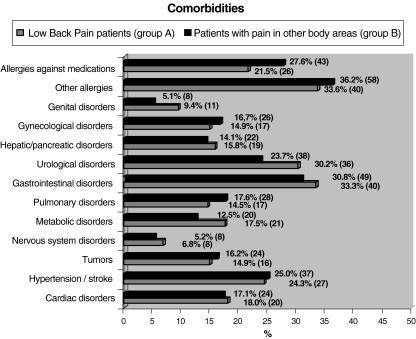

The most common comorbidities were gastrointestinal disease, allergies to pharmaceuticals, as well as hypertension and stroke (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences (p > 0.1) in medical comorbidities between the back pain patients and the patients with other forms of pain.

Fig. 1.

Comorbidities (Numbers in parenthesis indicate number of patients)

Prior medical care

There were highly significant differences between the two groups with regard to prior medical care and stays at rehabilitative facilities. Significantly more patients in group B than in group A were quoted to have a primary care physician (28.7 versus 14.9%). The number of patients who sought medical care in the previous six months was significantly greater in group B (34.5%) than for back pain patients (16.9%, p = 0.009). Likewise, significantly more patients in group B (64.9%) than back pain patients (37.1%) had not participated in rehabilitative therapy measures (p = 0.001).

Significantly more patients with other forms of chronic pain (28.7%) than back pain patients (14.9%) had not consulted a primary care physician (p = 0.03, Table 4).

Table 4.

Doctor’s visits and treatments in the last six months

| Medical care | Back pain patients (group A) | Patients with pain in other body areas (group B) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Have a primary care physician | Yes | 63 | 85.1 | 72 | 71.3 | |

| No | 11 | 14.9 | 29 | 28.7 | 0.03 | |

| Total | 74 | 100 | 101 | 100 | ||

| No response | 52 | 41.3 | 70 | 40.9 | ||

| Doctor’s visits in the last six months | None | 3 | 2.4 | 10 | 7.5 | 0.1 |

| No response | 26 | 20.6 | 38 | 22.2 | ||

| Medical treatments in the last six months | None | 18 | 16.9 | 46 | 34.5 | 0.009 |

| No response | 20 | 15.8 | 38 | 22.2 | ||

| Number of physicians consulted | None | 1 | 0.8 | 3 | 1.9 | 0.4 |

| No response | 12 | 9.5 | 16 | 9.3 | ||

| Hospital admissions | None | 51 | 43.9 | 75 | 48.7 | 0.5 |

| No response | 10 | 7.9 | 17 | 9.9 | ||

| Inpatient rehabilitative stays | None | 45 | 37.1 | 102 | 64.9 | 0.001 |

| No response | 5 | 3.9 | 14 | 8.1 | ||

| Operations because of pain | Yes | 45 | 37.8 | 48 | 29.6 | |

| No | 74 | 62.2 | 114 | 70.4 | 0.1 | |

| Total | 119 | 100 | 162 | 100 | ||

| No response | 7 | 5.8 | 9 | 5.5 | ||

| Operations for reasons other than pain | Yes | 80 | 68.4 | 107 | 68.6 | 0.9 |

| No | 37 | 31.6 | 49 | 31.4 | ||

| Total | 117 | 100 | 156 | 100 | ||

| No response | 9 | 7.6 | 15 | 9.6 | ||

The majority of patients had no history of pain-related hospital admission (43.9% of the patients in group A and 48.7% in group B). The majority of patients also had no pain-related past surgical history (62.2% of the patients in group A and 70.4% of the patients in group B).

However, 68.4% of the back pain patients and 68.6% of the patients with pain in other body areas reported having a prior operation for reasons unrelated to their pain.

In both samples, patients reported an average of at least one change of primary care physician, and the total number of physicians consulted was five among the back pain group and six among the patients with pain elsewhere in the body (Table 5). Back pain patients reported going to see a physician more often (14.7 visits) during the past six months, and also received more medical treatments, averaging 27.1 events. Patients with pain in other body regions averaged 11.6 visits and 16.5 medical treatments. The average number of stays at a rehabilitative facility was 2.6 for the back pain patients and 2.3 for those with pain in other body areas (Table 3).

Table 5.

Number of physicians consulted and medical treatments over six months

| Medical treatment | Back pain patients (group A) | Patients with pain in other body areas (group B) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum | N | Mean | Standard deviation | Minimum | Maximum | |

| Changes of primary care physician | 89 | 1 | 1.6 | 0 | 8 | 125 | 1.2 | 2.6 | 0 | 20 |

| Doctor’s visits over six months | 97 | 14..7 | 12.9 | 1 | 60 | 123 | 11.6 | 9.7 | 0 | 48 |

| Medical treatments over six months | 88 | 27.1 | 21.7 | 1 | 99 | 87 | 16.5 | 12.5 | 0 | 50 |

| Physicians consulted | 113 | 5.2 | 4.5 | 1 | 30 | 152 | 5.9 | 4.1 | 1 | 24 |

| Hospital admissions | 65 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 1 | 32 | 79 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 1 | 18 |

| Inpatient rehabilitative stays | 76 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 1 | 21 | 55 | 2.3 | 2 | 1 | 11 |

| Operations because of pain | 44 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 0 | 8 | 55 | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0 | 10 |

| Operations for reasons other than pain | 117 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 0 | 10 | 102 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 0 | 10 |

Discussion

This study aimed to establish how chronic low back pain patients differ in their subjective experience of the course of their illness from patients with chronic pain in other body regions. To this end the instrument of a validated pain questionnaire was used. A number of flaws in the study have to be addressed. First, the study was undertaken in an academic pain centre with chronic pain patients, which might lead to a selection bias and decrease the general relevance of its results. Also, the variation of pain over the course of time could be linked to system and sick leave policy. Third, a variable number of missing answers in some questions of the questionnaire might at times reduce the validity of the results.

General data and sociodemographic data

Recently, Chenot et al. [12] stated that women are more severely affected by low back pain and that they have a worse prognosis. In our study, in both groups women were overrepresented in a similar but not statistically significant extent. As we did not investigate the incidence of chronic low back pain within the population but compared two samples of patients with chronic pain in different body regions these differences became less apparent. Possibly, women are not only more severely affected by low back pain but also by pain emerging from other body regions. Recently, in a Canadian national epidemiologic survey involving more than 130,000 individuals, gender differences in depression and chronic pain conditions were described. In this study women reported higher rates of chronic pain conditions and depression and higher pain severity than men. The authors concluded that “depression and chronic pain conditions represent significant sources of disability, especially for women” [13].

Presumed aetiology of patients’ disorders

Significantly more back pain patients than those with pain in other body areas reported physical exertion as a possible cause for their illness (p = 0.001). This attribution, along with unilateral postural problems and frequent changes of position among the back pain patients, was highly significantly associated with increased pain (p = 0.001). It could be argued that this finding reflects a low degree of physical fitness among these patients. However, in a study by Mcquade et al., greater overall physical fitness significantly correlated with less physical dysfunction and fewer depressive symptoms, but not it did not correlate with psychological dysfunction or pain [14].

When asked to provide a possible aetiology for their pain, most of the patients with pain in other body regions (27.5%) named somatic diseases, with psychological stress being more closely associated with increased pain than among back pain patients.

Most patients included in our sample reported no similar pain symptoms among family members (82.2% and 85.6%, respectively).

Incorrect weightbearing [15] and non-physiological postures [16] were somatic factors involved in back pain becoming chronic. We also found that low back patients postulated physical demands significantly more often when asked to provide their subjective assessment of the pain’s aetiology. Testing the accuracy of this subjective assessment of the causal relationship between pain and its aetiology, however, was beyond the scope of this study.

Often, even substantial somatic problems do not necessarily lead to chronic pain [17]. Furthermore, Turk [18] identified physical exertion in combination with minimal formal education as a factor involved in pain in general becoming chronic. A study by Willweber-Strumpf et al. [19] found that most patients presenting to a primary care office postulated organic causes for their pain, while patients presenting to a neurological office postulated psychological stress as being causal. This shows that patients seek different medical specialists depending on the patient’s own internal attribution pattern. Therefore, subjectively experienced causes of a pain disorder can affect the clinical course [19].

The concept of a “pain family,“ such as by Violon and Giurgea [20] as well as Edwards et al. [21] is not supported by our study. Both studies determined there to be not only a congruency of pain symptoms, but also an increased frequency of pain among members of certain families.

Comorbidities

As shown in Fig. 1, the most commonly cited comorbidities were allergies (33.6% of back pain patients and 36.3% of patients with pain in other body areas) as well as gastrointestinal diseases (33.3% and 30.8%, respectively). From the questionnaire however it could not be deduced if these comorbidities occurred after or prior to the onset of low back pain.

In contrast, back pain patients in a study by Hestbaek et al. [22] most commonly complained of asthma and headache. Other authors found psychological disorders such as depression and anxiety disorders to be the most common comorbidities among chronic pain patients. A recent study by Ritzwoller et al. found very high incidences of physical diseases such as asthma, COPD, hypertension, and diabetes, as well as psychological disorders such as depression and substance abuse [23]. Older patients in particular demonstrate a strong correlation between back pain and physical comorbidities [24].

Doctor’s visits and medical treatments

Our results indicate that back pain patients visited an average of five different physicians because of their pain, while patients with pain in other body areas went to six different physicians. In both groups, those patients who changed their primary care physician on average did so only once. Significantly more general pain patients (28.7%) versus back pain patients (16.9%, p = 0.03) had no primary care physician. The number of back pain patients who did not seek therapy in the past six months (16.9%) or had not required inpatient rehabilitative measures (37.1%) was significantly less (p = 0.001 and p = 0.009, respectively) than the number of patients with pain in other body areas (34.5 and 64.9%, respectively; see Table 2).

The number of physicians consulted in our study matches that in a study by Nickel [25] in which patients sought out an average of six physicians in different specialties prior to being referred to a specialty pain centre. This underscores the often prolonged course of the disorder, including multiple iterations of the same diagnostic and therapeutic measures, which are relevant economically and contribute to the process of the pain becoming chronic. Physicians as well as patients contribute to this problematic process. Seitz et al. [26] illustrated the economic relevance of this point. According to their estimates, the direct treatment costs for back pain amount to five billion Euros annually in Germany, with rehabilitative measures making up one fifth of the total. Furthermore, Rose et al. [27] found that every third medical rehabilitative measure—from a total of 420,000—was prescribed in association with back pain.

In Germany, inpatient rehabilitative measures for chronic back pain showed only limited success [28]. Willweber-Strumpf et al. [19] found that in 30% of patients, none of the measures improved the patients’ pain. Possible causes for the poor success rate include the multifactorial and heterogenous aetiology of chronic pain as well as treatment deficits (few specialised institutions, long monodisciplinary therapy).

Predictors for chronicity

The number of unsuccessful therapies underscores the necessity for early initiation of effective interdisciplinary pain therapy. Because somatic and psychosocial factors are involved in an inter-related manner in the process of the pain becoming persistent, early therapy should include assessment and treatment of individual risk factors so that a clear somatic or psychosomatic treatment focus can be developed to break through these processes [29]. Numerous studies have attempted to identify prognostic factors for chronic low back pain. Recently, screening instruments for chronic low back pain were reviewed by Melloh et al. [30]. They found that the strongest predictors for the outcome variables “functional limitation” and “pain” psychological and occupational factors showed a high reliability for the prognosis of the patient with low back pain.

Further knowledge of how pain is individually perceived in pain syndromes generally and in low back pain in particular might facilitate the identification of individual risk factors in these patients and thus accelerate initiation of a targeted and effective therapy.

References

- 1.Horvath G, Koroknai G, Acs B, Than P, Illes T. Prevalence of low back pain and lumbar spine degenerative disorders. Questionnaire survey and clinical-radiological analysis of a representative Hungarian population. Int Orthop. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0920-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skovron ML, Szpalski M, Nordin M, Melot C, Cukier D. Sociocultural factors and back pain. A population-based study in Belgian adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:129–137. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199401001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papageorgiou AC, Croft PR, Ferry S, Jayson MI, Silman AJ. Estimating the prevalence of low back pain in the general population. Evidence from the South Manchester Back Pain Survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:1889–1894. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Cote P. The Saskatchewan health and back pain survey. The prevalence of low back pain and related disability in Saskatchewan adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:1860–1866. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199809010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO. At what age does low back pain become a common problem? A study of 29,424 individuals aged 12–41 years. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:228–234. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199801150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohlmann T, Schmidt C. Epidemiologie des Rückenschmerzes. In: Hildebrandt J, Müller G, Pfingsten M, editors. Lendenwirbelsäule: Ursachen, Diagnostik und Therapie von Rückenschmerzen. München: Urban und Fischer; 2005. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmermann M. Chronic pain. Epidemiology and management in Germany. Orthopade. 2004;33:508–514. doi: 10.1007/s00132-003-0609-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiser S, Rossignol M. Triage for nonspecific lower-back pain. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:147–155. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000200244.37555.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frymoyer JW, Cats-Baril W (1987) Predictors of low back pain disability. Clin Orthop Relat Res 221:89–98 [PubMed]

- 10.Frymoyer JW (1992) Predicting disability from low back pain. Clin Orthop Relat Res 279:101–109 [PubMed]

- 11.Nagel B, Gerbershagen HU, Lindena G, Pfingsten M. Development and evaluation of the multidimensional German pain questionnaire. Schmerz. 2002;16:263–270. doi: 10.1007/s00482-002-0162-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chenot JF, Becker A, Leonhardt C, Keller S, Donner-Banzhoff N, Hildebrandt J, Basler HD, Baum E, Kochen MM, Pfingsten M. Sex differences in presentation, course, and management of low back pain in primary care. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:578–584. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816ed948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munce SE, Stewart DE. Gender differences in depression and chronic pain conditions in a national epidemiologic survey. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:394–399. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.48.5.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McQuade KJ, Turner JA, Buchner DM (1988) Physical fitness and chronic low back pain. An analysis of the relationships among fitness, functional limitations, and depression. Clin Orthop Relat Res 233:198–204 [PubMed]

- 15.Le P, Solomonow M, Zhou BH, Lu Y, Patel V. Cyclic load magnitude is a risk factor for a cumulative lower back disorder. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49:375–387. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318046eb0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs JV, Henry SM, Nagle KJ. People with chronic low back pain exhibit decreased variability in the timing of their anticipatory postural adjustments. Behav Neurosci. 2009;123:455–458. doi: 10.1037/a0014479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kröner-Herwig B. Rückenschmerz. Göttingen: Hogrefe; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turk D. The role of demographic and psychosocial factors in transition from acute to chronic pain. In: Jensen T, Turner J, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, editors. 8th World congress on pain. Seattle: IASP Press; 1996. pp. 185–214. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willweber-Strumpf A, Zenz M, Bartz D. Epidemiology of chronic pain—an investigation in 5 medical practices. Schmerz. 2000;14:84–91. doi: 10.1007/s004820050226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Violon A, Giurgea D. Familial models for chronic pain. Pain. 1984;18:199–203. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90887-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards PW, Zeichner A, Kuczmierczyk AR, Boczkowski J. Familial pain models: the relationship between family history of pain and current pain experience. Pain. 1985;21:379–384. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Kyvik KO, Vach W, Russell MB, Skadhauge L, Svendsen A, Manniche C. Comorbidity with low back pain: a cross-sectional population-based survey of 12- to 22-year-olds. Spine. 2004;29:1483–1491. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000129230.52977.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritzwoller DP, Crounse L, Shetterly S, Rublee D. The association of comorbidities, utilization and costs for patients identified with low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-7-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudy TE, Weiner DK, Lieber SJ, Slaboda J, Boston JR. The impact of chronic low back pain on older adults: a comparative study of patients and controls. Pain. 2007;131:293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nickel R (1992) Das chronisch benigne Schmerzsyndrom: Demographische Parameter bei der Population einer Schmerzambulanz. Universität Mainz, Mainz, Germany

- 26.Seitz R, Schweikert B, Jacobi E, Tschirdewahn B, Leidl R. Economic rehabilitation management among patients with chronic low back pain. Schmerz. 2001;15:448–452. doi: 10.1007/s004820100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rose S, Irle H, Korsukewitz C. Orthopädische Rehabilitation der BfA. Stand Perspekt D Ang Vers. 2002;11:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huppe A, Raspe H. Efficacy of inpatient rehabilitation for chronic back pain in Germany: a systematic review 1980-2001. Rehabilitation (Stuttg) 2003;42:143–154. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schreiber B, Bandemer-Greulich U, Uhlemann K, Müller K, Müller-Pfeil L, Kreutzfeld A, Fikentscher E, Bahrke U. Behandlungsspezifik beim chronischen Rückenschmerz: Ist die optimierte Rehabilitationszuweisung ausreichend? Rehabilitation. 2004;43:142–151. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-814967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melloh M, Elfering A, Egli Presland C, Roeder C, Barz T, Rolli Salathe C, Tamcan O, Mueller U, Theis JC. Identification of prognostic factors for chronicity in patients with low back pain: a review of screening instruments. Int Orthop. 2009;33:301–313. doi: 10.1007/s00264-008-0707-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]