Abstract

Background

Current recommendations for rescue and resuscitation of people buried in avalanches are based on Swiss avalanche survival data. We analyzed Canadian survival patterns and compared them with those from Switzerland.

Methods

We extracted relevant data for survivors and nonsurvivors of complete avalanche burials from Oct. 1, 1980, to Sept. 30, 2005, from Canadian and Swiss databases. We calculated survival curves for Canada with and without trauma-related deaths as well as for different outdoor activities and snow climates. We compared these curves with the Swiss survival curve.

Results

A total of 301 people in the Canadian database and 946 in the Swiss database met the inclusion criteria. The overall proportion of people who survived did not differ significantly between the two countries (46.2% [139/301] v. 46.9% [444/946]; p = 0.87). Significant differences were observed between the overall survival curves for the two countries (p = 0.001): compared with the Swiss curve, the Canadian curve showed a quicker drop at the early stages of burial and poorer survival associated with prolonged burial. The probability of survival fell quicker with trauma-related deaths and in denser snow climates. Poorer survival probabilities in the Canadian sample were offset by significantly quicker extrication (median duration of burial 18 minutes v. 35 minutes in the Swiss sample; p < 0.001).

Interpretation

Observed differences in avalanche survival curves between the Canadian and Swiss samples were associated with the prevalence of trauma and differences in snow climate. Although avoidance of avalanches remains paramount for survival, the earlier onset of asphyxia, especially in maritime snow climates, emphasizes the importance of prompt extrication, ideally within 10 minutes. Protective devices against trauma and better clinical skills in organized rescue may further improve survival.

A valanches make winter outdoor travel in mountainous terrain a hazardous activity. A total of 881 people died from avalanches in open terrain in Europe and North America over the six winters from 2003/04 to 2008/09.1 The survival pattern of complete avalanche burials (coverage of the person’s head and chest, impairing breathing) in open terrain in Europe has been depicted in the avalanche survival curve,2,3 which displays probability of survival as a function of burial time. The curve exhibits a characteristic shape, with four distinct phases. The probability of survival remains above 91% during the first 18 minutes of burial (“survival phase”). This phase is followed by a precipitous drop to 34% between 19 and 35 minutes because of asphyxiation of most people (“asphyxia phase”). Between 35 and 90 minutes, the survival curve levels out (“latent phase”) because of the survival of people with patent airways.4 Thereafter, survival drops again as those buried eventually succumb to lethal hypothermia complicated by progressive hypoxia and hypercapnia.5

This avalanche survival model forms the foundation for current international recommendations for rescue and resuscitation3,4 as well as the rationale for safety and rescue devices.6 However, the existing survival curve was calculated solely from Swiss data. Therefore, the universal validity of the survival curve and recommendations derived from it remains unknown.

We analyzed survival curves for Canada and compared them with the survival curve in Switzerland. A better understanding of the factors affecting survival during an avalanche burial will provide important background for improvements in rescue, resuscitation and avalanche safety measures in Canada and elsewhere.

Methods

Data sources

We compiled avalanche survival data from existing databases of the Canadian Avalanche Centre and the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF in Switzerland. We obtained data for all complete avalanche burials (coverage of the person’s head and chest) that took place in open terrain between Oct. 1, 1980, and Sept. 30, 2005, for which information on the duration of burial and mortality was known.

Although both data sets included information on date and location of avalanche, type of outdoor activity (Box 1), duration of burial, burial depth and mortality, the Canadian data set also included information on cause of death (as determined by autopsy or external examination) and snow climate.

Box 1: Descriptions of outdoor activities.

Backcountry skiing: Downhill skiing or snowboarding on ungroomed and uncontrolled slopes away from ski areas; skiers or snowboarders reach slopes either under their own power using climbing skins or snowshoes (nonmechanized) or by using snowcats or helicopters (mechanized)

Off-piste skiing: Downhill skiing or snowboarding on ungroomed and uncontrolled slopes outside, but close to, ski areas; access primarily involves ski lifts and possibly short hikes to reach the top of the run

Snowmobiling: Use of small motorized vehicle that is propelled by rubber track and uses ski-like runners for steering

Alpinism: Mountaineering and ice climbing

The three snow climates — maritime, continental and transitional — are well established and have been used extensively to describe local snow and avalanche characteristics in western Canada (Box 2).7

Box 2: Snow climates used to describe snow and avalanche characteristics in western Canada7.

Maritime: The maritime Coast Mountains are characterized by abundant snowfall and relatively mild temperatures. Avalanches primarily involve snow from the most recent storm.

Continental: The continental Rocky Mountains are characterized by relatively low snowfall and cold temperatures. Avalanches involve snow from the most recent storm as well as older snow layers.

Transitional: The transitional Columbia Mountains exhibit intermediate characteristics.

In both countries, avalanche accidents are reported either by accident parties or by rescue agencies. Data on the duration of burial and burial depths most often represent best possible estimates that were entered into the respective databases from the information available after the accidents.

Statistical analysis

The Pearson χ2 and Mantel–Haenszel tests were used to compare nominal data. The Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to ordinal and non-normal data. We adjusted p values of multiple pair-wise comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. We considered p values of less than 0.05 to be statistically significant.

We calculated Canadian and Swiss survival curves using the nonparametric estimation procedure of Turnbull8,9 for doubly censored data. Because avalanche fatality records do not routinely distinguish between people who were dead on extrication and those who were alive on extrication but died during subsequent rescue, the resulting survival functions represent the combined effect of surviving the avalanche burial and the subsequent rescue efforts. We examined differences in survival curves using a procedure described by Dümbgen and colleagues.10 For the Canadian data set, we also calculated survival curves for asphyxia-related deaths only (to examine the effect of trauma on avalanche survival), for different snow climates and for outdoor activities where subsamples were sufficiently large.

Results

We obtained data for people who were completely buried in avalanches in Canada (n = 301) and Switzerland (n = 946) during the 25-year study period (Table 1). About two-thirds of the Canadian records were reported during the second half of the study period (Oct. 1, 1992, to Sept. 30, 2005); the Swiss data were more evenly split, with 48.2% of the records reported during the second half. With respect to type of outdoor activity (Box 1), the Canadian sample had a greater proportion of people involved in mechanized backcountry skiing and snowmobiling, whereas the Swiss sample had a significantly greater proportion involved in nonmechanized backcountry and off-piste skiing.

Table 1:

Characteristics of avalanche accidents involving complete burial of people in Canada and Switzerland from Oct. 1, 1980, to Sept. 30, 2005

| Characteristic | Country; no. (%) of people* | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canada n = 301 | Switzerland n = 946 | ||

| Period | < 0.001§ | ||

| Oct. 1, 1980, to Sept. 30, 1992 | 103 (34.2) | 490 (51.8) | |

| Oct. 1, 1992, to Sept. 30, 2005 | 198 (65.8) | 456 (48.2) | |

| Activity† | < 0.001§ | ||

| Backcountry skiing | 164 (54.5) | 507 (53.6) | |

| Nonmechanized | 98 (32.6) | 504 (53.3) | |

| Mechanized | 66 (21.9) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Off-piste skiing | 24 (8.0) | 286 (30.2) | |

| Snowmobiling | 65 (21.6) | 0 | |

| Alpinism | 16 (5.3) | 63 (6.7) | |

| Other | |||

| Recreational‡ | 20 (6.6) | 46 (4.9) | |

| Nonrecreational | 12 (4.0) | 44 (4.7) | |

| Depth of burial, cm, median (IQR) | n = 249 100 (50–180) | n = 879 80 (50–130) | < 0.001** |

| Duration of burial, min, median (IQR) | n = 301 18 (5–60) | n = 946 35 (12–120) | < 0.001** |

| Duration of burial, min | < 0.001§ | ||

| ≤ 10 | 124 (41.2) | 236 (24.9) | |

| 11–20 | 47 (15.6) | 142 (15.0) | |

| 21–35 | 29 (9.6) | 107 (11.3) | |

| 36–60 | 28 (9.3) | 117 (12.4) | |

| > 60 | 73 (24.3) | 344 (36.4) | |

| Cause of death | n = 143 | NA | – |

| Asphyxia | 116 (81.1) | ||

| Hypothermia | 0 | ||

| Trauma | 27 (18.9) | ||

Note: IQR = interquartile range, NA = not available.

Unless stated otherwise.

See Box 2 for definitions of the outdoor activities.

Includes hiking, snowshoeing and tobogganing.

Pearson χ2 test.

Mann–Whitney test.

The overall proportion of people who survived was 46.8% (583/1247), with no statistically significant differences between the Canadian and Swiss samples (Table 2). However, significant differences were observed when we examined survival by different intervals of burial duration (Table 2). The proportion of survivors in the two samples was comparable among people buried for 10 minutes or less. The proportion was significantly lower in Canada than in Switzerland among people buried for 11–20 minutes and among those buried for more than 35 minutes.

Table 2:

Proportion of people who survived complete burial in avalanches, by duration of burial

| Duration of burial, min | Canada

|

Switzerland

|

p value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. extricated | No. (%) who survived | No. extricated | No. (%) who survived | ||

| ≤ 10 | 124 | 111 (89.5) | 236 | 221 (93.6) | 0.95† |

| 11–20 | 47 | 17 (36.2) | 142 | 101 (71.1) | < 0.001† |

| 21–35 | 29 | 7 (24.1) | 107 | 47 (43.9) | 0.34† |

| ≥ 36 | 101 | 4 (4.0) | 461 | 75 (16.3) | 0.009† |

| All | 301 | 139 (46.2) | 946 | 444 (46.9) | 0.87‡ |

Mantel–Haenszel test for comparison of proportions of survivors stratified by duration of burial: p < 0.001.

Pearson χ2 test (with Bonferroni correction) for comparison of proportions of survivors in different intervals of burial durations.

Pearson χ2 test.

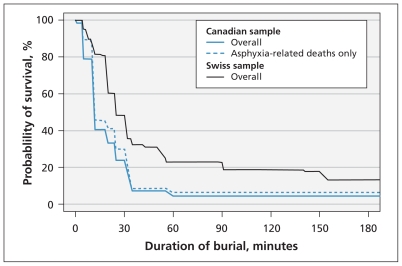

A comparison of the overall survival curves further highlighted differences between the two samples (Figure 1). Although the Swiss survival curve followed the general patterns described in earlier publications,2,3 the Canadian curve was characterized by an earlier (10 v. 18 minutes) and quicker drop in survival at the early stages of burial and poorer survival associated with prolonged burials.

Figure 1:

Overall survival curves for people completely buried in avalanches in Canada (n = 301) and Switzerland (n = 946) from Oct. 1, 1980, to Sept. 30, 2005, by duration of burial (Dümbgen comparison: p = 0.001). The dotted line represents the Canadian survival curve including only asphyxia-related deaths (n = 255).

The median duration of burial was significantly shorter in Canada than in Switzerland (Table 1). In the more detailed examination by duration of burial (Table 1 and Appendix 1, which is available at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/cmaj.101435/DC1), the proportion of people extricated within the first 20 minutes (companion rescue phase) was significantly higher in Canada (56.8%) than in Switzerland (40.0%). The proportion of people extricated after more than 60 minutes (organized rescue phase) was significantly lower in Canada (24.3%) than in Switzerland (36.4%).

The median depth of burial was significantly greater in Canada than in Switzerland (100 cm v. 80 cm; Table 1). However, the depth was closely tied to duration of burial (Spearman rank correlation r = 0.5, p < 0.001), and a comparison of survival at different depths of burial (Dümbgen comparison of people buried ≤ 80 v. > 80 cm in Switzerland: p = 0.24; people buried ≤ 100 v. > 100 cm in Canada: p = 0.83) showed that depth was most likely not an independent factor determining survival.

Of the 143 Canadian deaths with a known cause, 27 (18.9%) were due to trauma (Table 1). To examine the effect of trauma on avalanche survival, we calculated a survival curve for the Canadian sample that included only asphyxia-related deaths (Figure 1). This asphyxia-only curve was similar to the Swiss curve for the first 10 minutes of burial, after which differences in survival remained.

When we analyzed overall mortality in Canada by outdoor activity, we noted significant differences in proportions of people who died: back-country skiing 45.1% (74/164); off-piste skiing 41.7% (10/24); snowmobiling 72.3% (47/65); alpinism 87.5% (14/16); other, recreational, 60.0% (12/20); and other, nonrecreational, 41.7% (5/12) (Pearson χ2 test: p < 0.001). However, when we calculated survival curves for the first three activities (the last three were not included because the samples were too small), we found that they did not differ significantly (Dümbgen comparison of combined backcountry and off-piste skiing v. snowmobiling: p = 0.71). (See Appendices 2 and 3 for durations of burial and survival curves among skiers and snowmobilers, at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/cmaj.101435/DC1.)

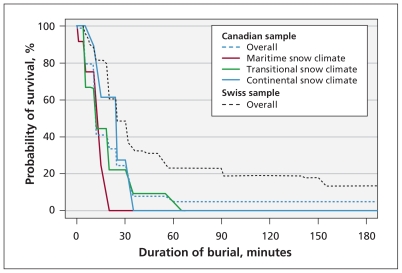

We observed significant differences in survival curves when we analyzed the Canadian data by snow climate (Figure 2). Overall mortality did not differ significantly between the climates (Table 3). Although the proportion of snowmobilers and alpinists was higher in the continental snow climate; the transitional climate had a higher proportion of skiers (Table 3). The median duration of burial was significantly longer in the continental snow climate than in the transitional and maritime snow climates (Table 3 and Appendix 1). The depth of burial differed significantly only between the continental and transitional data sets. The proportion of trauma-related deaths was significantly higher in the transitional snow climate than in the other two snow climates.

Figure 2:

Survival curves in Canada by snow climate (maritime, n = 36; transitional, n = 132; and continental, n = 101) (Dümbgen comparison of continental v. transitional: p = 0.017; continental v. maritime: p = 0.008; transitional v. maritime: p = 0.33). Overall survival curves for the Canadian and Swiss samples (dotted lines) are shown for comparison.

Table 3:

Characteristics of avalanche accidents in Canada, by snow climate* (n = 269)

| Characteristic | Snow climate; no. (%) of people† | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continental n = 101 | Transitional n = 132 | Maritime n = 36 | ||

| Period | 0.44§ | |||

| Oct. 1, 1980, to Sept. 30, 1992 | 39 (38.6) | 40 (30.3) | 17 (47.2) | |

| Oct. 1, 1992, to Sept. 30, 2005 | 62 (61.4) | 92 (69.7) | 19 (52.8) | |

| Activity‡ | < 0.001§ | |||

| Backcountry skiing | 47 (46.5) | 92 (69.7) | 13 (36.1) | |

| Nonmechanized | 42 (41.6) | 42 (31.8) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Mechanized | 5 (5.0) | 50 (37.9) | 6 (16.7) | |

| Off-piste skiing | 9 (8.9) | 7 (5.3) | 7 (19.4) | |

| Snowmobiling | 28 (27.7) | 26 (19.7) | 4 (11.1) | |

| Alpinism | 10 (9.9) | 0 | 5 (13.9) | |

| Other | ||||

| Recreational | 3 (3.0) | 4 (3.0) | 5 (13.9) | |

| Nonrecreational | 4 (4.0) | 3 (2.3) | 2 (5.6) | |

| Mortality | 0.44§ | |||

| Survivors | 44 (43.6) | 67 (50.8) | 15 (41.7) | |

| Nonsurvivors | 57 (56.4) | 65 (49.2) | 21 (58.3) | |

| Depth of burial, cm | n = 78 | n = 108 | n = 32 | 0.013** |

| Median (IQR) | 150 (80–200) | 100 (50–50) | 100 (50–150) | |

| Duration of burial, min | n = 101 | n = 132 | n = 36 | |

| Median (IQR) | 25 (10–90) | 12.5 (4–30) | 15 (2–30) | 0.002†† |

| Cause of death | n = 52 | n = 62 | n = 19 | 0.004§ |

| Asphyxia | 47 (90.4) | 43 (69.4) | 18 (94.7) | |

| Hypothermia | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Trauma | 5 (9.6) | 19 (30.6) | 1 (5.3) | |

Note: IQR = interquartile range.

See Box 1 for descriptions of snow climates.

Unless stated otherwise.

See Box 2 for definitions of outdoor activities.

Pearson χ2 test.

Kruskal–Wallis test; significant pair-wise comparisons included continental–transitional snow climates (Bonferroni-corrected p value = 0.014).

Kruskal–Wallis test; significant pair-wise comparisons included continental–transitional snow climates (Bonferroni-corrected p value = 0.004) and continental–maritime snow climates (Bonferroni-corrected p value = 0.035).

Interpretation

Our study offers insights into avalanche survival patterns in Canada. We found significant differences in the overall survival curves betwen the two samples. Even though avalanche rescue equipment and strategies have steadily improved over the study period and the Canadian data set was shifted toward more recent years, the Canadian survival curve showed lower chances of survival at all burial durations compared with the Swiss survival model, with a quicker drop in survival in the first 35 minutes and poorer survival associated with prolonged burials. However, the poorer survival curves for Canada were offset by significantly quicker extrication times, which resulted in comparable proportions of survivors in the Canadian and Swiss samples.

In the Canadian sample, trauma accounted for more than half of the deaths among people extricated in the first 10 minutes (Figure 1), which highlights the strong influence of trauma on the early phases of the survival curve. The probability of survival at the end of the first 10 minutes was 77% in the overall survival curve for Canada, as compared with 86% in the asphyxia-only survival curve (Figure 1), which highlights the impaired survival phase. However, this presentation reflects only the magnitude of trauma on avalanche survival among completely buried people. In a recent study of avalanche-related deaths in Canada, 33% of all nonsurvivors had major trauma, and only half of the trauma-related deaths involved people who had been completely buried.11 In addition, 44% of those who had a trauma-related death had severe trauma (injury severity score12,13 ≥ 50), which likely resulted in death shortly after burial regardless of extrication time. The study also showed that two-thirds of the trauma-related deaths involved collisions with trees.

When we analyzed the data further to examine reasons for the shape of the Canadian survival curve, we observed significant differences in the survival functions for different snow climates. The survival curves for the transitional and maritime snow climates were characterized by a considerably earlier drop in survival compared with the curve for the continental snow climate. The density and arrangement of avalanche debris may affect the supply of oxygen to avalanche victims.5 In addition, denser debris would apply greater compressive forces, thus preventing chest movement.14 Snow density is defined as the overall mass of snow per unit volume (kilograms per meter cubed). Typical densities of seasonal snow vary from 30 kg/m3 in dry, newly fallen snow to 600 kg/m3 in wet spring snow.7 General estimates of the density of typical avalanche debris range from 200 to 600 kg/m3 depending on factors such as snowpack density and debris moisture.7 Armstrong and Armstrong15 provided rough reference values for typical densities of new snow for different climates, ranging from 120 kg/m3 in the maritime climate to 70 kg/m3 in the continental snow climate.

Although the initial drop in the survival curve in the transitional snow climate was worsened by a higher prevalence of trauma in this region, other observed differences in the distribution of outdoor activities and depths of burial were unable to explain the observed progression in the onset of asphyxia across the snow climates. We therefore conclude that differences in snow climate accounted for the remaining differences in the first 35 minutes of burial. This conclusion is supported by the similarity of the early stages of the survival curves in the Swiss sample and the continental snow climate in the Canadian sample, since the snow climate of Switzerland has been described as transitional to partly continental.16–18

These results highlight the importance of prompt extrication by companions,19,20 especially in areas with a more maritime snow climate. Although the “survival phase” has commonly been described to be about 18 minutes long,3 our analysis shows that the first 10 minutes might be a more appropriate general guideline for Canada and other areas with a maritime snow climate. The use of avalanche airbags to prevent burial and avalanche transceivers to speed up the location of buried avalanche victims are recommended. Both of these safety devices have been shown to reduce mortality significantly.6 Furthermore, efficient shovelling techniques21 can result in critical time savings during extrication.

Compared with the Swiss survival curve, the Canadian curve showed poorer survival associated with prolonged burials, across all snow climates. Because the available records did not distinguish between people who were dead on extrication and those who died later, this difference may have been due to limitations in clinical skills at the scene and during transport as well as to long distances to receive advanced care. The two longest burials among survivors in the Canadian sample (120 and 300 minutes) both occurred in urban settings, whereas the maximum burial time among survivors in a remote setting was 55 minutes. Although the survival of people recovered by organized rescue efforts has been reported to be only 18%,20 resuscitation of people with asphyxia and hypothermia should proceed according to established recommendations3,4,22,23 to optimize likelihood of survival.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. Our retrospective analysis of observational data was naturally restricted by the limitations of the available data sets. The cause of death was not reported in the Swiss data, and the samples available for subgroup analysis of the Canadian data were small.

Although data collected on avalanche-related deaths are generally of high quality, nonfatal involvements with avalanches are commonly underreported. This leads to an inherent underestimation of the true survival function, particularly during the early stages of burial. In addition, although reported burial times are likely randomly biased, possible systematic inconsistencies could also affect calculations of survival curves. However, we have no indication that these limitations are different between Canada and Switzerland.

Even though the collection of accurate data is naturally not a priority during avalanche rescues, better information on the condition of avalanche victims at extrication, resuscitation measures, injuries of survivors and environmental conditions such as density of the snow slab are crucial for improving our understanding of the factors contributing to avalanche survival and for estimating more precise avalanche survival curves.

Conclusion

We found significant differences in survival curves between Canadian and Swiss samples of people completely buried in avalanches. Although the presence of four distinct phases in the survival curve seems to be universal, their duration and contribution to survival are modified by local factors. Our analysis highlights the effects of trauma and snow climate on avalanche survival. Efficient rescue by companions immediately after burial must be encouraged in all snow climates, and organized rescue must be perceived with its much higher mortality. Although safety devices that protect against trauma and asphyxiation are recommended, they should be considered ancillary. Rescue teams need to be educated in avalanche resuscitation techniques. In addition, protocols are needed for more efficient evacuation to appropriate treatment centres, including tertiary care centres for extracorporeal rewarming of people with severe hypothermia. However, given the quick drop in survival associated with complete avalanche burials, emphasis on education and avoidance of avalanches remains paramount for promoting safety during winter outdoor travel in mountainous terrain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Canadian Avalanche Centre and the WSL Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research SLF in Switzerland for providing access to the accident information and their continuous efforts to collect high-quality avalanche accident data; Walter Würtl, Peter Paal and Peter Mair for thoughtful discussions on the observed differences in avalanche survival; Avisualanche Consulting for providing administrative support; and the Institute of Mountain Emergency Medicine at the European Academy of Bozen/Bolzano (EURAC) for facilitating a meeting of the research group in Innsbruck.

See related commentary by Grissom at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/doi/10.1503/cmaj.110347.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributions: The study was conceived and designed by Pascal Haegeli and Jeff Boyd. The Swiss dataset was extracted by Hans-Jürg Etter. Pascal Haegeli extracted the Canadian dataset and merged it with the Swiss dataset for the analysis. Pascal Haegeli and Markus Falk conducted the statistical analyses. Jeff Boyd and Hermann Brugger contributed medical insight during the analysis and for the interpretation of the results. Pascal Haegeli drafted the article, and all of the authors made critical revisions and gave final approval of the manuscript. Pascal Haegeli was responsible for the overall supervision and coordination of the study.

Funding: No external funding was received for this research.

References

- 1.People rescued from snow avalanches 2003/04, 2004/05, 2005/06, 2006/07, 2007/08, and 2008/09. International Commission for Alpine Rescue; 2004–2009. Available: www.ikar-cisa.org/eXtraEngine3/WebObjects/eXtraEngine3.woa/wa/menu?id=298&lang=en (accessed 2010 Sept. 28).

- 2.Falk M, Brugger H, Adler-Kastner L. Avalanche survival chances. Nature 1994;368:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brugger H, Durrer B, Adler-Kastner L, et al. Field management of avalanche victims. Resuscitation 2001;51:7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd J, Brugger H, Shuster M. Prognostic factors in avalanche resuscitation: a systematic review. Resuscitation 2010;81:645–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brugger H, Sumann G, Meister R, et al. Hypoxia and hypercapnia during respiration into an artificial air pocket in snow: implications for avalanche survival. Resuscitation 2003;58:81–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brugger H, Etter H-J, Zweifel B, et al. The impact of avalanche rescue devices on survival. Resuscitation 2007;75:476–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClung DM, Schaerer PA. The avalanche handbook. 3rd ed Seattle (WA): The Mountaineers; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turnbull BW. Nonparametric estimation of a survivorship function with doubly censored data. J Am Stat Assoc 1974;96:169–73 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giolo SR. Turnbull’s nonparametric estimator for interval-censored data [technical report]. Paraná (Brazil): Department of Statistics, University of Paraná; 2004. Available: www.est.ufpr.br/rt/suely04a.htm (accessed 2010 Sept. 28). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dümbgen L, Freitag-Wolf S, Jonbloed G. Estimating a uni-modal distribution from interval-censored data. J Am Stat Assoc 2006;101:1094–106 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd J, Haegeli P, Abu-Laban RB, et al. Patterns of death among avalanche fatalities: a 21 year review. CMAJ 2009;180:507–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker SP, O’Neill B, Haddon WJ, et al. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma 1974;14:187–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Champion HR, Copes WS, Sacco WJ, et al. The major trauma outcome study: establishing national norms for trauma care. J Trauma 1990;30:1356–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stalsberg H, Albertsen C, Gilbert M, et al. Mechanism of death in avalanche victims. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopatho1 1989;414:415–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Armstrong RL, Armstrong BR. Snow and avalanche climates of the western United States: a comparison of maritime, intermountain and continental conditions. IAHS Publication 1987;162: 281–94 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schweizer J, Wiesinger T. Snow profile interpretation for stability evaluation. Cold Reg Sci Technol 2001;33:179–88 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schweizer J, Jamieson JB. A threshold sum approach to stability evaluation of manual snow profiles. Cold Reg Sci Technol 2007; 47:50–9 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schweizer J, Bellaire S. On stability sampling strategy at the slope scale. Cold Reg Sci Technol 2010;64:104–9 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hohlrieder M, Mair P, Wuertl W, et al. The impact of avalanche transceivers on mortality from avalanche accidents. High Alt Med Biol 2005;6:72–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hohlrieder M, Thaler S, Wuertl W, et al. Rescue missions for totally buried avalanche victims: conclusions from 12 years experience. High Alt Med Biol 2008;9:229–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genswein M, Eide R. The V-shaped snow conveyor belt. Proceedings of International Snow Science Workshop Whistler 2008. 2008. September 21–27; Whistler, BC: p. 571–8 Available: http://arc.lib.montana.edu/snow-science/objects/P__8248.pdf (accessed 2011 Mar. 2). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanden Hoek TL, Morrison LJ, Shuster M, et al. Part 12.10: cardiac arrest in avalanche resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation 2010;122(Suppl 3): S829–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soar J, Perkins GD, Abbas G, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 8. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances: Electrolyte abnormalities, poisoning, drowning, accidental hypothermia, hyperthermia, asthma, anaphylaxis, cardiac surgery, trauma, pregnancy, electrocution. Resuscitation 2010;81:1400–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.