Abstract

Background

Readmissions to hospital are increasingly being used as an indicator of quality of care. However, this approach is valid only when we know what proportion of readmissions are avoidable. We conducted a systematic review of studies that measured the proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable. We examined how such readmissions were measured and estimated their prevalence.

Methods

We searched the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases to identify all studies published from 1966 to July 2010 that reviewed hospital readmissions and that specified how many were classified as avoidable.

Results

Our search strategy identified 34 studies. Three of the studies used combinations of administrative diagnostic codes to determine whether readmissions were avoidable. Criteria used in the remaining studies were subjective. Most of the studies were conducted at single teaching hospitals, did not consider information from the community or treating physicians, and used only one reviewer to decide whether readmissions were avoidable. The median proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable was 27.1% but varied from 5% to 79%. Three study-level factors (teaching status of hospital, whether all diagnoses or only some were considered, and length of follow-up) were significantly associated with the proportion of admissions deemed to be avoidable and explained some, but not all, of the heterogeneity between the studies.

Interpretation

All but three of the studies used subjective criteria to determine whether readmissions were avoidable. Study methods had notable deficits and varied extensively, as did the proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable. The true proportion of hospital readmissions that are potentially avoidable remains unclear.

In most instances, unplanned readmissions to hospital indicate bad health outcomes for patients. Sometimes they are due to a medical error or the provision of suboptimal patient care. Other times, they are unavoidable because they are due to the development of new conditions or the deterioration of refractory, severe chronic conditions.

Hospital readmissions are frequently used to gauge patient care. Many organizations use them as a metric for institutional or regional quality of care.1 The widespread public reporting of hospital readmissions and their use in considerations for funding implicitly suggest a belief that readmissions indicate the quality of care provided by particular physicians and institutions.

The validity of hospital readmissions as an indicator of quality of care depends on the extent that readmissions are avoidable. As the proportion of readmissions deemed to be avoidable decreases, the effort and expense required to avoid one readmission will increase. This decrease in avoidable admissions will also dilute the relation between the overall readmission rate and quality of care. Therefore, it is important to know the proportion of hospital readmissions that are avoidable.

We conducted a systematic review of studies that measured the proportion of readmissions that were avoidable. We examined how such readmissions were measured and estimated their prevalence.

Methods

Literature search

We consulted a local information scientist to develop a search strategy to identify studies that measured the proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/cmaj.101860/DC1). We applied this strategy to search the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases for English-language papers published from 1966 to July 2010. Full-text versions of citations were retrieved for complete review if they specified that hospital readmissions were counted; and the title or abstract used any term(s) indicating that readmissions were classified as avoidable (or “preventable,” “needless” or “unnecessary”) or not.

We included studies if they included a population of hospital readmissions and if they counted the number of readmissions that they classified as avoidable. The references of all included studies were reviewed to identify other eligible analyses. In addition, we reviewed the links of all PubMed “related articles” of each included study.

Data abstraction

Data abstracted from each study included basic study information (publication year, journal); inclusion criteria for, and numbers of, index admissions and readmissions; follow-up period after index admission within which readmissions were considered; whether or not information from potential sources (e.g., index admission, clinic visits between index and readmission, readmission, interviews with treating physicians or nurses, interviews with patients or families) were used when determining avoidability of readmissions; and the criteria required for readmissions to be classified as avoidable.

We abstracted the number of reviewers used (per readmission) and whether or not readmissions attributable to specific groups or factors were considered avoidable. We searched for these groups or factors in the methods section and in descriptions of avoidable readmissions in each study and classified them as treating physician (e.g., medical errors, omissions of care); nurse (e.g., inadequate dressings); patient (e.g., noncompliance with therapy); social (e.g., inability of family to care for patient in community); and system (e.g., home care unavailable).

Two of us (C.B. and A.J.) independently abstracted data from a random sample of 10 studies to compare agreement and implement abstraction criteria to harmonize abstraction. Subsequently, a single reviewer (C.B. or A.J.) abstracted data from all of the remaining studies. All abstractions were reviewed and confirmed by the lead author (C.v.W.).

Statistical analysis

Basic descriptive statistics for each study were calculated. To explore study heterogeneity, we created a meta-regression model that measured the association of study factors with the proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable. The three studies that used administrative data to identify avoidable readmissions were methodologically distinct from the others and did not define many of the variables required for the meta-regression. We therefore grouped these three studies together and included the remaining studies in the the meta-regression model. Study factors that were not defined were defaulted to null for our model.

Model building used 13 candidate binary variables (e.g., year study was published; use of administrative databases; number of reviewers involved; length of follow-up period; factors included, and sources of information used, in determining avoidability of readmissions; location and type of hospital; type of hospital service to which patients were admitted; and whether or not limited number of diagnoses included). In the models, studies were weighted by the inverse of the variance for the proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable. Ordinal and continuous variables were transformed into binary variables by their median values. This created a model that allowed us to group studies based on values of each independently significant covariate. We used forward selection methods to identify the study factors that had the strongest independent association with the proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable. We limited the regression model to three covariates (about 10 observations per covariate) to avoid overfitting.2 To determine goodness of fit, we calculated the Akaike information criterion value for all possible three-variable models.

Studies were grouped based on their values of the binary covariates included in the final meta-regression model. To calculate the overall proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable for studies in each group, we weighted studies by the inverse of their variance.3 Heterogeneity of results within each group was measured using the Cochran Q and the I2 statistics.3,4

Results

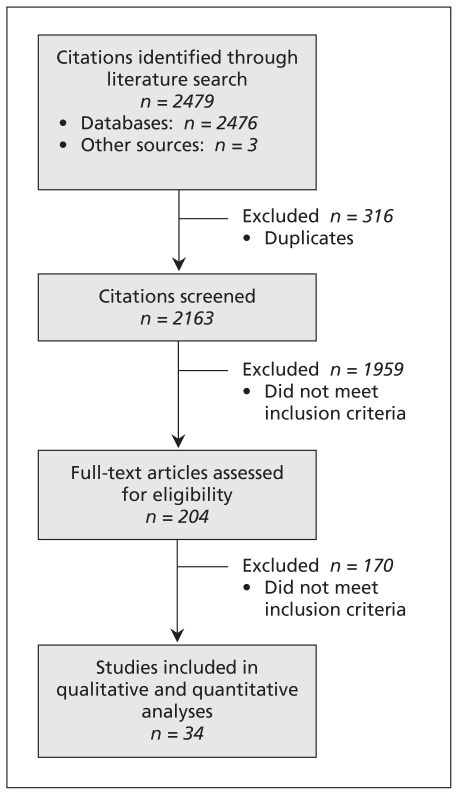

Figure 1 presents the results of our search strategy. After screening 2163 citations, we reviewed the full-text articles of 204 studies. Thirty-four of the studies measured the proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable.5–38

Figure 1:

Selection of studies that measured the proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable.

A summary of the studies’ characteristics appears in Table 1. The included studies were published between 1983 and 2009 (median year 2000). Most of the studies were conducted at single centres; almost two-thirds were conducted primarily in teaching hospitals. Patients were most commonly admitted to medical, surgical and geriatric services. Most of the studies included all readmissions regardless of the diagnosis; four (12.5%) restricted readmissions to particular diagnoses, including congestive heart failure,16,38 diabetes,16 obstructive lung disease16 and adverse drug reactions.34 Half of the studies limited readmissions to those that occurred within three months after discharge. Most of the studies were moderately sized, with a median of 151 readmissions (interquartile range [IQR] 75–313). Studies originated primarily from the United Kingdom5,8–10,13–15,21,24–26,31,36–38 and the United States.7,11,12,16–18,22,27,33

Table 1:

Summary of characteristics of 34 studies that measured the proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable

| Variable | No. (%) of studies* |

|---|---|

| Study characteristics | |

| Year of publication, median (IQR) | 2000 (1993–2005) |

| No. of hospitals per study, median (range) | 1 (1–234) |

| Conducted at single centre (n = 31)† | 26 (83.9) |

| Conducted primarily in teaching hospitals (n = 28)‡ | 18 (64.3) |

| Index admission used as unit of analysis§ | 19 (55.9) |

| No. of index admissions, median (IQR) (n = 19)** | 1289 (743–3050) |

| Follow-up period for readmission, mo, median (IQR) | 2 (1–6) |

| No. of readmissions, median (IQR) | 151 (75–313) |

| Type of patient | |

| Medical | 25 (73.5) |

| Surgical | 13 (38.2) |

| Geriatric | 11 (32.4) |

| Assessment of avoidability (n = 31)†† | |

| Information used for assessment | |

| Index admission | 25 (80.6) |

| Clinical visits between index admission and readmission | 10 (32.3) |

| Readmission | 27 (87.1) |

| Interviews with physician or nurse†† | 7 (22.6) |

| Interviews with patient or family†† | 9 (29.0) |

| Groups or factors included in assessment | |

| Physician | 28 (90.3) |

| Nurse | 2 (6.5) |

| Patient | 7 (22.6) |

| Social | 16 (51.6) |

| System | 5 (16.1) |

| Minimum no. of reviewers, median (range) | 1 (1–3) |

| One reviewer only | 17 (54.8) |

| Outcomes | |

| No. of readmissions deemed avoidable, median (IQR) | 35 (17–70) |

| % of readmissions deemed avoidable, median (IQR) | 27.1 (14.9–45.6) |

| % of index admissions followed by an avoidable | 2.2 (1.5–7.0) |

| readmission, median (IQR) (n = 19) | |

Note: IQR = interquartile range.

Unless stated otherwise.

The unit of analysis was the readmission in the other 15 studies.

The denominator comprises the 19 studies in which the unit of analysis was the index admission.

Criteria used to identify avoidable readmissions

Criteria used to identify avoidable readmissions varied extensively between the studies (see Table 2, at the end of the article). Three studies18,27,33 used only administrative data in their analyses and classified readmissions based on combinations of diagnostic codes between the index admission and the readmission. For example, in the study by Goldfield and colleagues, all readmissions with a diagnostic code of diabetes for which the index admission had a diagnostic code of myocardial infarction were classified as avoidable.33

Table 2:

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis (part 1 of 4)

| Study | No. of hospitals (no. teaching) | Patient age, yr | Hospital services | Diagnoses considered in avoidability assessment | Time frame, mo | Sources of information for avoidability assessment* | Factors included in determining avoidability† | Minimum no. of reviewers per readmission | Criteria for avoidable readmissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graham5 | 1 (0) | NR | NR | NR | 12 |  |

|

1 | Inadequate medical management, social problems or inadequate rehabilitation |

| Popplewell6 | 1 (1) | All | M | All | 2 |  |

|

1 | Readmission avoidable with better management of index admission |

| MacDowell7 | 1 (1) | NR | M, S | All (non-psychiatric) | 3 |  |

|

3 | Unplanned, not a complication of chronic disease that caused index admission and not due to new disease |

| McInness8 | 1 (0) | > 65 | G | All (non-surgical) | 3 |  |

|

1 | Included groups from study by Graham5: inadequate medical management, social problems or inadequate rehabilitation |

| Williams9 | 1 (0) | > 65 | All | NR | 1 |  |

|

1 | Readmission avoidable with better preparation and timing of discharge, help for carer, communication with GP, nursing and social supports, and management of medications |

| Clarke10 | NR (NR) | NR | M, S, G | NR | 1 |  |

|

3 | Recurrence or continuation of admission diagnosis; recognized avoidable complication; or readmission for social or psychological reason within control of hospital services |

| Vinson11 | 1 (1) | > 70 | NR | CHF | 3 |  |

|

1 | Avoidability based on degree that potentially remediable factors (noncompliance with diet/medications; inadequate discharge planning; inadequate follow-up by GP or home care; active family involvement) contributed to readmission |

| Frankl12 | 1 (1) | NR | M | NR | 1 |  |

|

3 | NR |

| Kelly13 | 1 (1) | NR | NR | NR | 12 |  |

|

2 | Readmission avoidable with better treatment, rehabilitation or discharge planning |

| Gautam14 | 1 (0) | NR | G | NR | 1 |  |

|

3 | At least two of three (GP, consultant and audit team) deemed readmission avoidable |

| Haines-Wood15 | 1 (0) | “Elderly” | R | NR | 6 |  |

|

1 | Recurrence or continuation of admission diagnosis; recognized avoidable complication; or readmission for social reason within control of hospital services |

| Oddone16 | 9 (6) | NR | M | DM, CHF, COPD | 6 |  |

|

2 | At least two of three reviewers rated readmission avoidable |

| McKay17 | 1 (1) | NR | NR | NR | 1 |  |

|

1 | NR |

| Experton18 | 6 (NR) | > 65 | All | All | 3 | – | – | – | Administrative database study. Readmission considered possibly avoidable if adverse utilization-related factors present, including potentially premature discharge from index admission, or suboptimal care after discharge (inadequate physician follow-up care, inpatient rehabilitation, skilled nursing, home care services or other outpatient care); quantitative criteria given for each factor |

| Kwok19 | 1 (1) | ≥ 70 | M | NR | 6 |  |

|

1 | Noncompliance with medication or diet; unresolved medical problems; adverse effects of medications; social or psychological problems |

| Miles20 | 1 (1) | NR | All | NR | 1 |  |

|

1 | Poor or inappropriate clinical care (i.e., ≥ 4 on 6-point scale), and preventability rated at least “more likely than not” (i.e., ≥ 4/6) |

| Levy21 | 1 (1) | NR | M | NR | 1 |  |

|

1 | Consultant reviewed medical notes and judged whether readmission was potentially avoidable |

| Madigan22 | NR (NR) | NR | NR | CHF | 3 |  |

|

1 | Avoidability based solely on opinion of treating home care nurse |

| Halfon23 | 1 (1) | All (no newborns) | All (no ophthalmology or psychiatry) | NR | 12 |  |

|

1 | Premature discharge (clinical instability in last 2 days, last laboratory result was abnormal or other); missing or erroneous diagnosis or therapy; other inadequate discharge; or reviewers deemed readmission to be complication of medical care rather than natural history of disease |

| Munshi24 | 1 (1) | > 65 | M | NR | 1 |  |

|

3 | Medical or social problem identified at index admission but not completely addressed; or complication of treatment |

| Sutton25 | 3 (3) | All | S | All | 1 |  |

|

2 | NR |

| Courtney26 | 1 (1) | NR | S | NR | 1 |  |

|

1 | NR |

| Friedman27 | NR (NR) | NR | All | All | 6 | – | – | – | Administrative database study |

| Jimenez-Puente28 | 1 (0) | NR | NR | NR | 6 |  |

|

2 | Complication of surgical procedure; procedure not performed during index admission; surgery not achieving proposed objective; no diagnosis during index admission or other potentially avoidable cause (nosocomial infection, suboptimal medical treatment, unstable condition at discharge, inadequate use of drugs [wrong dosage, interaction], complication of diagnostic test, nonadherence because of inadequate information) |

| Maurer29 | 1 (1) | NR | M | NR | 3 |  |

|

1 | Recurrence or continuation of index disorder; avoidable complication; or readmission for social or psychological reason within control of hospital services |

| Halfon (2006)30 | 12 (NR) | NR | NR | NR | 1 |  |

|

1 | Premature discharge; wrong diagnosis or treatment; foreseeable but preventable complications of care |

| Kirk31 | 1 (0) | All | M | All | 1 |  |

|

1 | Clinician reviewed medical record and interviewed patient to gauge readiness for discharge and appropriateness of readmission |

| Balla32 | 1 (1) | NR | M | NR | 1 |  |

|

2 | Quality of care deemed poor because of incorrect action (erroneous drug, dose or both; diagnostic error; unnecessary test, procedure or drug) or inaction (early discharge; inadequate work-up; disregard of significant test result; failure to treat problem or monitor drug levels) |

| Goldfield33 | 234 (NR) | NR | No obstetrics, neonates | No cancer, trauma, burns or cystic fibrosis | 0.5 | – | – | – | Administrative database study |

| Ruiz34 | 1 (1) | NR | NR | NR | 2 |  |

|

3 | Any adverse drug event |

| Stanley35 | 1 (0) | NR | NR | NR | 7 |  |

|

1 | Any correctable factors that might have prevented the readmission |

| Witherington36 | 1 (1) | NR | NR | NR | 1 |  |

|

2 | At least 2 of 3 reviewers felt readmission was related to adverse drug event from: new drug; withdrawal due to discontinuation of drug for no reason; medication that patient was supposed to stop; or condition untreated during previous admission |

| Phelan37 | 1 (1) | NR | NR | NR | 12 |  |

|

2 | Deterioration of condition requiring readmission took more than 24 h and could have been managed on outpatient basis (no arrhythmia or ischemia) |

| Shalchi38 | 1 (0) | NR | NR | NR | 0.5 |  |

|

3 | At least 2 of 3 reviewers felt readmission was avoidable with better management of index admission |

Note: CHF = chronic heart failure, COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, DM = diabetes mellitus, G = geriatric, GP = general practitioner, M = medical, NR = not reported, R = rehabilitation, S = surgical.

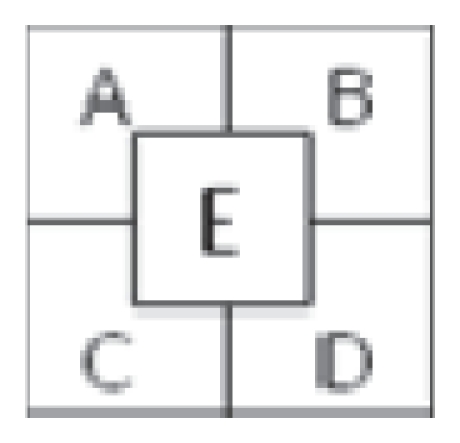

Each box uses the scheme at the right and represents a source of information used in the avoidability assessment: A = index admission, B = clinic visits between index admission and readmission, C = readmission, D = interviews with physician, E = interviews with patient/family.

Each box uses the scheme at the right and represents a factor included when determining avoidability: A = physician, B = nurse or other allied health professional, C = patient, D = social, E = system.

Criteria used in the rest of the studies fell into one of four general groups. Four studies did not specify the criteria used to classify readmissions, stating that reviewers judged which readmissions were avoidable.12,17,25,26 Eleven studies described criteria that were subjective, citing few or no qualifiers or guides for reviewers.6,13,14,16,21,22,24,31,35,37,38 Three studies used criteria that focused exclusively on adverse drug reactions.20,34,36 Miles and Lowe used methods similar to those in studies of adverse events, with a defined six-point scale to determine whether readmissions were avoidable.20

In the fourth group, 13 studies used criteria with several qualifiers provided to define “avoidable,” often providing categories for avoidable readmissions.5,7–11,15,19,23,28–30,32 Several studies within this category were notable: Graham and Livesley classified readmissions into one of five groups,5 and their methods were the most commonly replicated in other studies; MacDowell and colleagues used an algorithmic method to identify avoidable readmissions;7 and Halfon and coauthors provided detailed and specific criteria to determine avoidability stratified by phases of patient care.23

Perhaps with the exception of criteria dealing exclusively with adverse drug events, criteria used to identify avoidable readmissions were subjective and left reviewers much room to make decisions regarding whether or not readmissions were avoidable.

We noted large variations between studies in the application of criteria (Table 1). Of the 31 studies that indicated the number of reviewers involved in determining the avoidability of each readmission, most (17, 54.8%) used only one reviewer; the maximum number was three reviewers per readmission (7 studies, 22.6%). Studies varied in the sources of information used to determine avoidability. Most included information abstracted from the medical record of the index admission (25 studies, 80.6%) or the readmission (27 studies, 87.1%). Information from clinic notes between the index admission and readmission were used in about one-third of the studies. Information from interviews with treating physicians and patients was used in less than one-third of the studies. Finally, studies varied on whether or not readmissions attributable to specific groups or factors were considered avoidable. The most common factors included actions or omissions on the part of treating physicians or hospitals (28 studies, 90.3%). All of the other factors, including those attributable to the patient (7 studies, 22.6%) and social issues (16 studies, 51.6%), were much less commonly considered when determining the avoidability of readmissions.

Proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable

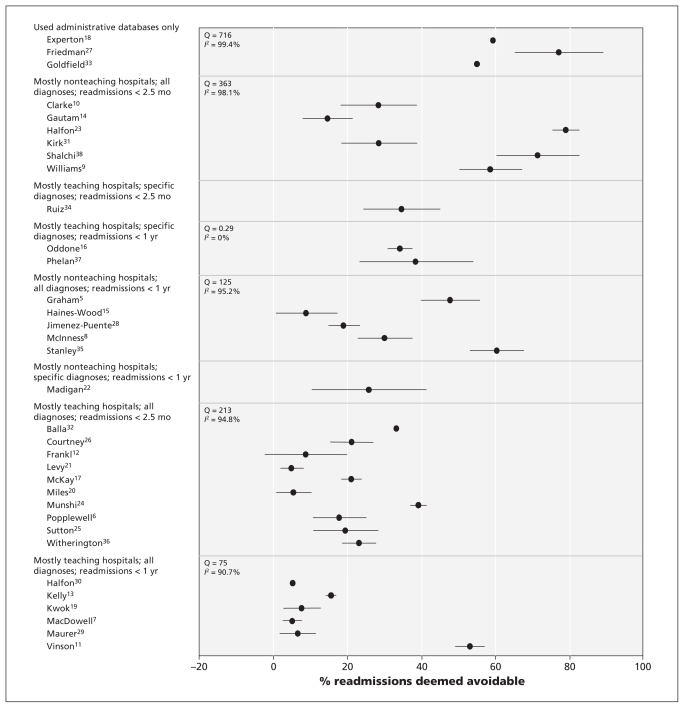

The proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable varied extensively between the studies (Tables 1 and 3). The median unweighted proportion was 27.1%, although the range was 5.0%–78.9% (Figure 2, Table 3). In the 19 studies that used the index admission as the unit of analysis, avoidable readmissions were noted in a median of 2.2% of discharges (IQR 1.5%–7.0%).

Table 3:

Results of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | No. of index admissions* | No. of readmissions (% of index admissions) | No. (%) of readmissions deemed avoidable | % of index admissions followed by an avoidable readmission* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graham5 | – | 153 | 73 (47.7) | – |

| Popplewell6 | 978 | 73 (7.5) | 13 (17.8) | 1.3 |

| MacDowell7 | – | 78 | 4 (5.1) | – |

| McInness8 | – | 153 | 46 (30.1) | – |

| Williams9 | – | 133 | 78 (58.6) | – |

| Clarke10 | – | 74 | 21 (28.4) | – |

| Vinson11 | 140 | 66 (47.1) | 35 (53.0) | 25.0 |

| Frankl12 | 2 626 | 318 (12.1) | 28 (8.8) | 1.1 |

| Kelly13 | – | 211 | 33 (15.6) | – |

| Gautam14 | 713 | 109 (15.3) | 16 (14.7) | 2.2 |

| Haines-Wood15 | 84 | 45 (53.6) | 4 (8.9) | 4.8 |

| Oddone16 | 1 262 | 811 (64.3) | 277 (34.2) | 21.9 |

| McKay17 | 3 705 | 289 (7.8) | 61 (21.1) | 1.6 |

| Experton18 | 190 | 48 (25.3) | 37 (77.1) | 19.5 |

| Kwok19 | 1 204 | 455 (37.8) | 35 (7.7) | 2.9 |

| Miles20 | – | 437 | 24 (5.5) | – |

| Levy21 | 2 484 | 262 (10.5) | 13 (5.0) | 0.5 |

| Madigan22 | 114 | 31 (27.2) | 8 (25.8) | 7.0 |

| Halfon23 | 3 474 | 1 115 (32.1) | 59 (5.3) | 1.7 |

| Munshi24 | 3 706 | 179 (4.8) | 70 (39.1) | 1.9 |

| Sutton25 | – | 297 | 58 (19.5) | – |

| Courtney26 | 1 914 | 52 (2.7) | 11 (21.2) | 0.6 |

| Friedman27 | 345 651 | 122 015 (35.3) | 67 108 (55.0) | 19.4 |

| Jimenez-Puente28 | – | 363 | 69 (19.0) | – |

| Maurer29 | 773 | 151 (19.5) | 10 (6.6) | 1.3 |

| Halfon30 | – | 494 | 390 (78.9) | – |

| Kirk31 | 1 289 | 77 (6.0) | 22 (28.6) | 1.7 |

| Balla32 | 1 913 | 271 (14.2) | 90 (33.2) | 4.7 |

| Goldfield33 | 3 501 142 | 409 759 (11.7) | 242 991 (59.3) | 6.9 |

| Ruiz34 | – | 81 | 28 (34.6) | – |

| Stanley35 | – | 141 | 85 (60.3) | – |

| Witherington36 | – | 108 | 25 (23.1) | – |

| Phelan37 | – | 39 | 15 (38.5) | – |

| Shalchi38 | – | 63 | 45 (71.4) | – |

Studies for which no value is shown are those that considered readmission as the unit of analysis.

Figure 2:

Proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable. Studies are grouped based on the value of study factors with the strongest association with this outcome (Table 4). Error bars = 95% confidence intervals.

Many study-level factors were reported to be associated with the proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable (Table 4). In the univariable analysis, studies that used administrative data had notably higher proportions of avoidable readmissions than studies that used other criteria. Proportions of readmissions deemed avoidable were significantly higher in studies in which patients were from medical services than in studies without such patients or in which patient type was not specified. Studies reporting the lowest proportions of avoidable readmissions included those conducted primarily in teaching hospitals and those that only included avoidable readmissions due to physician factors. Surprisingly, studies that involved more than one reviewer per case had higher proportions of avoidable readmissions than those involving one reviewer.

Table 4:

Association between study-level factors and proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable in binomial regression models*

| Study-level factor | Weighted overall proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted

|

Adjusted

|

|||||

| In studies with factor | In studies without factor | p value | In studies with factor | In studies without factor | p value | |

| Used administrative databases | 59.0 | 11.7 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Included patients on medical wards† | 59.0 | 20.0 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Included surgical patients† | 9.3 | 18.0 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Included geriatric patients† | 9.3 | 18.0 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| > 1 reviewer | 24.6 | 9.3 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Limited to specific diagnoses | 34.2 | 10.0 | < 0.001 | 74.0 | 23.1 | < 0.001 |

| Only readmissions because of physician factors considered avoidable | 9.5 | 17.9 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Publication year ≥ 2000 | 10.5 | 14.1 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Follow-up period for readmissions of up to 1 yr after discharge‡ | 9.0 | 20.9 | < 0.001 | 36.8 | 59.4 | < 0.001 |

| > 2 sources of information used to determine avoidability of readmissions | 24.6 | 9.6 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Mostly teaching hospitals in study | 8.7 | 53.4 | < 0.001 | 20.8 | 76.4 | < 0.001 |

| Study from United States | 25.5 | 9.9 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Study from United Kingdom or Ireland | 15.6 | 11.4 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

This table summarizes the results of univariable and multivariable binomial regression models that measured the association of study-level factors with the proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable. With the exception of the first factor (administrative database study), all analyses excluded the three studies that used administrative databases alone.18,27,33

Compared with studies that excluded such patients or that did not specify patient type.

Compared with studies that had a follow-up period of up to 2.5 months after discharge.

In the multivariable analysis, the three study-level factors associated with significantly high proportions of avoidable readmissions (and therefore retained in the model) were limiting of readmissions to those with specific diagnoses, a follow-up period of up to one year after the index admission and having teaching hospitals make up the majority of hospitals in the study (Table 4). This model had the lowest Akaike Information Criterion goodness-of-fit value (658) of all possible three-variable models in our study.

The three factors in our multivariable model explained some of the heterogeneity in the study results. In Figure 2, we grouped studies based on their values for the three binary covariates that made it into the final model (Table 4). Within each group, we calculated the weighted proportion of avoidable readmissions for the group, the Cochran Q value and the I2 value. In three combinations of study-level factors, heterogeneity was resolved (Figure 2), but only one of these groups (with the three factors of mostly teaching hospitals, specific diagnoses and readmissions within one year after discharge) contained more than one study. That significant heterogeneity persists after clustering studies based on the most important study-level factors indicates the extensive amount of heterogeneity in these studies.

Interpretation

Readmissions to hospital are increasingly being used as a quality-of-care measure. They can indicate quality of care, however, only if an important proportion of them are deemed avoidable. In our systematic review, we identified 34 studies that measured the proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable. Subjective criteria and variable methods were used in every study. The proportions of readmissions deemed avoidable varied widely between the studies. This variability makes it difficult to state with any certainty how often readmissions are preventable. Nevertheless, the median proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable (27.1%) is certainly lower than the 76% reported in 2007 by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission to the US Congress.39 Although the variation seen in these studies could reflect true differences in quality of patient care, it also reflects the subjectivity of the outcome itself as well as differences in study characteristics, including patient and hospital types included; factors considered in determining avoidability of readmissions; sources of information used to judge avoidable status; and the minimum number of reviewers per case.

Although subjectivity will always exist when determining whether readmissions are avoidable, steps can be taken to minimize resulting error. First, parameters required for reviewing readmissions — such as which factors responsible for a readmission (e.g., physician, nurse, patient) are classified as avoidable — need to be clarified. Second, the use of multiple reviewers is essential when dealing with subjective outcomes such as avoidable readmissions. Because the accuracy of reviews is never perfect, the use of multiple reviewers helps ensure that patient classifications are as accurate as possible. Finally, latent class models can be used to analyze multiple reviews and generate the probability that each patient truly had an avoidable readmission.40–42 We believe that such models may be useful to classify avoidable readmissions more reliably.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. First, although we used a clear and sensible search strategy that identified a large number of studies, we may have missed relevant publications. In addition, we limited studies to those published in English. However, given the large number of studies included in our review, it is unlikely that our overall conclusions would change meaningfully if any missed studies were included.

Second, we used transparent meta-regression modelling to identify the most important sources of heterogeneity between studies. Although we limited this model to three covariates to avoid overfitting of the model, significant heterogeneity remained. This finding is not unexpected given the extensive amount of heterogeneity between the studies (Figure 2). In addition, the model’s outcome (proportion of readmissions deemed avoidable) will have notable error in it because of the subjectivity involved in the classification of readmissions as avoidable or not. This error will not be captured by the study-level factors in our regression model.

Third, we combined studies from different health care systems. Although some factors contributing to the proportion of avoidable readmissions are likely universal (e.g., incorrect diagnosis), other factors influencing readmission rates that are unique to particular health care systems (e.g., health insurance coverage) will not be captured in our model.

Finally, we were unable to summarize disease-specific proportions of avoidable readmissions, because they were rarely reported in studies that included a broad assortment of diseases. Future studies would need to address this issue to identify possible diseases that could be targeted for interventions to decrease the risk of avoidable readmissions.

Conclusion

Our study showed that the proportion of hospital readmissions deemed avoidable has yet to be reliably determined. Furthermore, we found a lack of consensus regarding the methods necessary to judge whether readmissions are avoidable. Given the large variation in the proportion of avoidable readmissions between studies using primary data, “avoidability” cannot accurately be inferred based on diagnostic codes for the index admission and the readmission. Instead, it needs to be determined through a peer-review process in which readmissions are classified as avoidable or not based on expert opinion.

Criteria used in future studies need to focus on determining whether the readmission was preceded by an adverse event (i.e., a bad medical outcome due to medical care rather than the natural history of disease or bad luck); whether the adverse event could have been prevented; and whether the readmission would have occurred even without the adverse event or whether other factors were involved. In addition, future studies need to include a large number of readmissions in a broad spectrum of patients from multiple teaching and community hospitals; multiple sources of patient information between index admission and readmission on which decisions regarding avoidabililty are based; an explicit statement about which groups or factors contributing to readmissions are considered avoidable; at least three reviewers per readmission to judge avoidability; and the use of structural modelling methods such as the latent class model to measure the probability that patients truly had an avoidable readmission based on the judgments of reviewers.

Supplementary Material

See related commentary by Goldfield at www.cmaj.ca/cgi/doi/10.1503/cmaj.110448

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study and the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data. Carl van Walraven, Peter Austin and Alan Forster drafted the article; all of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted for publication. Carl van Walraven had full access to all of the data in the study; he takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This study was supported by the Department of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ont.

References

- 1.Office of the Auditor General of Ontario 2010 annual report — discharge of hospital patients.Toronto (ON): Government of Ontario; 2010. p. 64–93 Available: www.auditor.on.ca/en/reports_en/en10/302en10.pdf (accessed 2011 Mar. 11) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrell FE. Multivariable modeling strategies. Regression modelling strategies. New York (NY): Springer; 2001. p. 53–86 [Google Scholar]

- 3.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham H, Livesley B. Can readmissions to a geriatric medical unit be prevented? Lancet 1983;1:404–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popplewell PY, Chalmers JP, Burns RJ, et al. A review of early medical readmissions at the Flinders Medical Centre. Aust Clin Rev. 1984;11:3–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDowell NM, Hunter SA, Ludke RL. Readmissions to a Veterans Administration medical center. J Qual Assur 1985;7:20–3 [Google Scholar]

- 8.McInnes EG, Joshi DM, O’Brien TD. Failed discharges: setting standards for improvement. Geriatric Medicine. 1988;18:35–42 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams EI, Fitton F. Factors affecting early unplanned readmission of elderly patients to hospital. BMJ 1988;297:784–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke A. Are readmissions avoidable? BMJ 1990;301:1136–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vinson JM, Rich MW, Sperry JC, et al. Early readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:1290–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frankl SE, Breeling JL, Goldman L. Preventability of emergent hospital readmission. Am J Med 1991;90:667–74 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly JF, McDowell H, Crawford V, et al. Readmissions to a geriatric medical unit: Is prevention possible? Aging (Milano) 1992;4:61–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gautam P, Macduff C, Brown I, et al. Unplanned readmissions of elderly patients. Health Bull (Edinb) 1996;54:449–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haines-Wood J, Gilmore DH, Beringer TR. Re-admission of elderly patients after in-patient rehabilitation. Ulster Med J 1996; 65:142–4 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oddone EZ, Weinberger M, Horner M, et al. Classifying general medicine readmissions. Are they preventable? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies in Health Services Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmissions. J Gen Intern Med 1996;11:597–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKay MD, Rowe MM, Bernt FM. Disease chronicity and quality of care in hospital readmissions. J Healthc Qual 1997;19:33–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Experton B, Ozminkowski RJ, Pearlman DN, et al. How does managed care manage the frail elderly? The case of hospital readmissions in fee-for-service versus HMO systems. Am J Prev Med 1999;16:163–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwok T, Lau E, Woo J, et al. Hospital readmission among older medical patients in Hong Kong. J R Coll Physicians Lond 1999; 33:153–6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miles TA, Lowe J. Are unplanned readmissions to hospital really preventable? J Qual Clin Pract 1999;19:211–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy A, Alsop K, Hehir M, et al. Hospital readmissions. We’ll meet again. Health Serv J 2000;110:30–1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madigan EA, Schott D, Matthews CR. Rehospitalization among home healthcare patients: results of a prospective study. Home Healthc Nurse 2001;19:298–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halfon P, Eggli Y, van Melle G, et al. Measuring potentially avoidable hospital readmissions. J Clin Epidemiol 2002;55:573–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munshi SK, Lakhani D, Ageed A, et al. Readmissions of older people to acute medical units. Nurs Older People 2002;14:14–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutton CDM. Leicestershire surgical readmissions survey. J Clin Excellence 2002;4:33–41 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Courtney ED, Ankrett S, McCollum PT. 28-Day emergency surgical re-admission rates as a clinical indicator of performance. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2003;85:75–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedman B, Basu J. The rate and cost of hospital readmissions for preventable conditions. Med Care Res Rev 2004;61:225–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiménez-Puente A, Garcia-Alegria J, Gomez-Aracena J, et al. Readmission rate as an indicator of hospital performance: the case of Spain. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2004;20:385–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maurer PP, Ballmer PE. Hospital readmissions — Are they predictable and avoidable? Swiss Med Wkly 2004;134:606–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Halfon P, Eggli Y, Pretre-Rohrbach I, et al. Validation of the potentially avoidable hospital readmission rate as a routine indicator of the quality of hospital care. Med Care 2006;44:972–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirk E, Prasad MK, Abdelhafiz AH. Hospital readmissions: patient, carer and clinician views. Acute Medicine. 2006;5:104–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balla U, Malnick S, Schattner A. Early readmissions to the department of medicine as a screening tool for monitoring quality of care problems. Medicine 2008;87:294–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldfield NI, McCullough EC, Hughes JS, et al. Identifying potentially preventable readmissions. Health Care Financ Rev 2008;30:75–91 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruiz B, Garcia M, Aguirre U, et al. Factors predicting hospital readmissions related to adverse drug reactions. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008;64:715–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanley A, Graham N, Parrish A. A review of internal medicine re-admissions in a peri-urban South African hospital. S Afr Med J 2008;98:291–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witherington EM, Pirzada OM, Avery AJ. Communication gaps and readmissions to hospital for patients aged 75 years and older: observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:71–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phelan D, Smyth L, Ryder M, et al. Can we reduce preventable heart failure readmissions in patients enrolled in a disease management programme? Ir J Med Sci 2009;178:167–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shalchi Z, Saso S, Li HK, et al. Factors influencing hospital readmission rates after acute medical treatment. Clin Med 2009; 9:426–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Report to the Congress: promoting greater efficiency in Medicare. Washington (DC): The Commission; 2007. p.107–8 Available: www.medpac.gov/documents/jun07_entirereport.pdf(accessed 2011 Mar. 11) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Coomarasamy A, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic tests when there is no gold standard. A review of methods. Health Technol Assess 2007:11:iii, ix-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goetghebeur E, Liinev J, Boelaert M, et al. Diagnostic test analyses in search of their gold standard: latent class analyses with random effects. Stat Methods Med Res 2000;9:231–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Formann AK, Kohlmann T. Latent class analysis in medical research. Stat Methods Med Res 1996;5:179–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.