Abstract

Background and Aims

Several animals that live on bromeliads can contribute to plant nutrition through nitrogen provisioning (digestive mutualism). The bromeliad-living spider Psecas chapoda (Salticidae) inhabits and breeds on Bromelia balansae in regions of South America, but in specific regions can also appear on Ananas comosus (pineapple) plantations and Aechmea distichantha.

Methods

Using isotopic and physiological methods in greenhouse experiments, the role of labelled (15N) spider faeces and Drosophila melanogaster flies in the nutrition and growth of each host plant was evaluated, as well as seasonal variation in the importance of this digestive mutualism.

Key Results

Spiders contributed 0·6 ± 0·2 % (mean ± s.e.; dry season) to 2·7 ± 1 % (wet season) to the total nitrogen in B. balansae, 2·4 ± 0·4 % (dry) to 4·1 ± 0·3 % (wet) in An. comosus and 3·8 ± 0·4 % (dry) to 5 ± 1 % (wet) in Ae. distichantha. In contrast, flies did not contribute to the nutrition of these bromeliads. Chlorophylls and carotenoid concentrations did not differ among treatments. Plants that received faeces had higher soluble protein concentrations and leaf growth (RGR) only during the wet season.

Conclusions

These results indicate that the mutualism between spiders and bromeliads is seasonally restricted, generating a conditional outcome. There was interspecific variation in nutrient uptake, probably related to each species' performance and photosynthetic pathways. Whereas B. balansae seems to use nitrogen for growth, Ae. distichantha apparently stores nitrogen for stressful nutritional conditions. Bromeliads absorbed more nitrogen coming from spider faeces than from flies, reinforcing the beneficial role played by predators in these digestive mutualisms.

Keywords: Bromelioideae, Bromelia balansae, Ananas comosus, pineapple, Aechmea distichantha, chlorophylls and carotenoid, soluble protein, spider–bromeliad interactions, stable isotope 15N, nitrogen flux

INTRODUCTION

Plant performance can be strongly influenced by predators (Herrera and Pellmyr, 2002; Knight et al., 2006). For example, it is well known that predators can reduce plant fitness by capturing or chasing away pollinators (Knight et al., 2006; Gonçalves-Souza et al., 2008). In contrast, plant performance can be improved if predators reduce the damage to floral tissues caused by phytophages (Rico-Gray and Oliveira, 2007; Romero et al., 2008a). However, there is a less-known phenomenon by which predators can improve plant performance by contributing to plant nutrition (Romero et al., 2006). To date, the most common examples of this type of nutritional interaction are from ant–plant systems (Treseder et al., 1995; Sagers et al., 2000; Fischer et al., 2003; Solano and Dejean, 2004), from digestive mutualism involving Pameridea bugs (Miridae) and their carnivorous host plant Roridula (Ellis and Midgley, 1996; Anderson and Midgley, 2002, 2003) and from amphibians and spiders that inhabit bromeliads (Romero et al., 2006; Inselsbacher et al., 2007; Romero et al., 2010). In this kind of mutualism animals contribute to plant nutrition and performance, and receive variable benefits from the plants.

Plants of the large Neotropical family Bromeliaceae can shelter numerous organisms, including bacteria, algae, fungi, invertebrates, vertebrates and even vascular plants (Gutiérrez et al., 1993; Benzing, 2000; Machado and Oliveira, 2002; Romero, 2006). Associations between spiders and Bromeliaceae are widespread in South America (Romero and Vasconcellos-Neto, 2005a; Romero, 2006). For instance, Romero (2006) reported that nine species of the spider family Salticidae live in association with Bromeliaceae in diverse types of vegetation in various regions ranging from Brazil, Bolivia, Argentina and Paraguay. Some bromeliads are terrestrial with well-developed root systems and their leaves forming rosettes that contribute little to nutrient uptake (Benzing, 1986, 2000). Many bromeliad species have adaptations that allow them to occupy xeric, nutrient-poor environments (Benzing, 2000). Some of them are tank based, being dependent on animals for nutrition. Others are myrmecophytes with ant-houses or ant-nest gardens and, finally, some of them are atmospherics with a dense indumentum of absorbing hairs where the substrates serve primarily for anchorage (Benzing, 1986, 2000). Bromeliad leaves are organized in rosettes that sometimes accumulate rain water (phytotelmata), and have trichomes on the foliage surface which are specialized for absorbing water and nutrients. Additionally, the organisms associated with Bromeliaceae may contribute to plant nutrition and performance. However, despite a growing knowledge of the number of associations between predators and Bromeliaceae, so far only a few studies have evaluated their role as digestive mutualists of Bromeliaceae (Romero et al., 2006, 2008b, 2010).

Digestive mutualism involving animals and Bromeliaceae was first suggested by Benzing (1986) and empirically sustained by Romero et al. (2006, 2008b) which showed that the Neotropical jumping spider Psecas chapoda (Salticidae) provides the terrestrial bromeliad Bromelia balansae with nitrogen derived from its debris (e.g. faeces). Psecas chapoda inhabits and breeds almost exclusively on this bromeliad species in several regions of South America, including Brazil, Bolivia and Paraguay (Romero, 2006). In this by-product mutualism (see Romero et al., 2008b), the bromeliad architecture can benefit spiders by providing foraging, mating and egg-laying sites, shelter against predators and fire, and nurseries for spiderlings (Romero and Vasconcellos-Neto, 2005a, b, c; Omena and Romero, 2008). In turn, bromeliads can absorb nutrients from spider debris (e.g. faeces, spider silk, prey carcass and exuviae) through specialized leaf trichomes or roots (Romero et al., 2006, 2008b).

In addition to B. balansae, P. chapoda also inhabit two other Bromelioideae species: the commercial Ananas comosus (pineapple) and Aechmea distichantha. Since these three Bromelioideae species have variable life styles and modes of nutrient uptake, these spider–plant systems are suitable for testing animal contributions to plant nutrition and performance in the Bromelioideae subfamily.

In this study, isotopic (15N) and physiological methods were used to evaluate the contribution of P. chapoda faeces as a nitrogen source in sustaining the nutrition and growth of B. balansae, An. comosus and Ae. distichantha, and the seasonal variation in these spider–bromeliad relationships. In addition, 15N-labelled Drosophila melanogaster flies were used to test whether insects that eventually fall into the bromeliad rosette and phytotelmata are also a source of nutrients for these plants. Specifically, this study addresses the following questions. (a) Which bromeliad species derives the most nitrogen from spider faeces? (b) Does seasonal variation affect the absorption of the nitrogen originating from P. chapoda? (c) Do concentrations of chlorophylls, carotenoid and soluble protein change in response to the nitrogen obtained from P. chapoda? (d) Does the nitrogen from P. chapoda affect the growth of the three bromeliad species over dry and wet seasons?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms and experiment design

Pineapple (Ananas comosus) is typically found in large plantations, but also grows naturally in cerrado vegetation and semi-deciduous forests in South America (Romero, 2006). Like Bromelia balansae this species has well-developed roots for acquiring nutrients (Benzing, 1986, 2000). Bromelia balansae and An. comosus do not have phytotelmata, but they are able to accumulate a few millimetres of rain water at the base of their rosettes (Romero et al., 2006). Aechmea distichantha is terrestrial, epiphytic or lithophilic, has phytotelmata (Borgo and Silva, 2003; Romero et al., 2007) and poorly developed roots, which have the nearly exclusive function of attaching the rosette to the substrate (Benzing, 1986, 2000). Of these three bromeliads, Ae. distichantha has more developed and numerous epidermic trichomes, which are specialized in acquiring complex nitrogen molecules (e.g. amino acids) (Martin, 1994; Benzing, 2000). In contrast, B. balansae and An. comosus have trichome foliage that apparently does not absorb complex organic nutrients (Benzing, 2000). Whereas B. balansae is a C3 plant, the photosynthetic pathways of An. comosus and Ae. distichantha are based on crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM; Martin, 1994). Since the water-conservative CAM mode of photosynthesis often occurs in epiphytic species, especially in those lacking the phytotelmata and in terrestrial species that occupy arid sites (Martin, 1994), CAM species are expected to depend more on foliar uptake of spider faeces.

To test the seasonal variation on the contribution of Psecas chapoda to the nutrition and growth of B. balansae, An. comosus and Ae. distichantha, experiments were conducted in the dry (from 9 May to 5 July 2006) and wet (from 4 March to 30 April 2007) seasons. The average monthly rainfall in the dry season (May to July) varied from 25 to 38 mm and the minimum and maximum temperatures were 13 °C and 28 °C, respectively. In the wet season (March and April) the rainfall reached 413 mm, with a minimum temperature of 20 °C and a maximum temperature of 32 °C (INPE/CPTEC, 2008).

In this experiment small young bromeliads with similar biomass and size (foliar length varying from 20 to 25 cm) were used to minimize the effect of nitrogen dilution. Moreover, all plants had an equivalent size to those plants that support up to two P. chapoda individuals (6th to 8th instars; Romero et al., 2006). Bromelia balansae plants were obtained from seeds from the same cohort. Ananas comosus plants were obtained from pineapple crowns and Ae. distichantha plants were collected from mountain-top rocky outcrops in Monte Verde, Minas Gerais State, in the south-eastern Brazil region. All bromeliads were planted in pots (14·5 cm in diameter, 14·5 cm high). These bromeliads remained for 6 months and 1 year in a greenhouse before the start of the experiments in the dry and wet seasons, respectively. This procedure was important to avoid any contact of the bromeliads with spiders or other organisms and to allow acclimation of plants. Each bromeliad species was raised according to its type of substratum: during the two experiments (dry and wet seasons), B. balansae was kept in a nutrient poor sandy soil (the same type of soil used by Romero et al., 2006) and Ae. distichantha was kept in triturated Pinus sp. bark because this is an epiphytic bromeliad. In the first experiment (dry season) An. comosus plants were kept in a reddish-yellow clay soil with medium sandy texture, while in the second experiment (wet season) they were kept in the same sandy soil used for B. balansae. Any variation in 15N values among soils from pots was not relevant here once the bromeliads received enriched debris. All plants were kept in a net greenhouse (mesh diameter: 1 mm) exposed to seasonal conditions (dry and wet). The plants were watered with limited amounts of water, just enough to avoid excessive desiccation; for this, an automatic irrigation system using three fine spraying sprinklers, each with a capacity of 6L h−1, which worked for 15 min every 6 h, was employed.

Nitrogen flux from spiders to bromeliads

To quantify the nitrogen flux from spiders to bromeliads, spiders were fed 15N-labelled Drosophila melanogaster flies and their faeces were stored for later application to the bromeliads. The flies were cultured from eggs in a medium of 15N-labelled yeast. The labelled yeast was obtained by raising commercial yeast on a Difco-Bacto carbon-based medium with ammonium sulfate [(15NH4)2SO4, 10 % excess atoms, from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, MA, USA]. Details of the laboratory procedure for yeast and fly enrichment can be found in Romero et al. (2006).

Fifty P. chapoda females (between 6th and 8th instars) were collected in the field (São José do Rio Preto municipality, São Paulo State) from B. balansae and kept in glass flasks of approx. 7 cm diameter and 10 cm in height. Each spider was fed every 3 d with 15 enriched flies, an interval sufficient for the spider to capture all the flies and produce faeces (see Romero et al., 2006). At 3-d intervals the faeces in each flask was diluted in 500 µL distilled water and then frozen and stored in polypropylene tubes. Additionally, at 3-d intervals, 15 flies were frozen (–18 °C) for use in the experiments.

In the dry-season experiment, B. balansae, An. comosus and Ae. distichantha specimens were treated in one of two ways: (1) every 3 d they received faeces produced by two spiders (n = 5 plants) or (2) received no faeces (n = 5 plants). In the wet-season experiment, B. balansae, An. comosus and Ae. distichantha specimens were treated in one of three ways: (1) every 3 d they received faeces produced by two spiders (n = 5 plants); (2) every 3 d they received one enriched fly (n = 5 plants); or (3) they received no faeces or flies (n = 5 plants). Thawed flies and faeces were applied to the central part of the rosette and the tank of the bromeliads at the base of the leaves. The biomass of spider faeces and flies used in the different treatments was similar, i.e. two spiders produced 0·24 ± 0·04 mg faeces (n = 4) every 3 d, whereas one fly weighed 0·23 ± 0·02 mg (n = 6). These biomass values did not differ statistically (t-test: P = 0·636). The water in the Ae. distichantha tank came from the irrigation system (subterraneous water) and rainwater. The original water found in this species in the field was not maintained in the experiment since macro- and microorganisms could affect the results of isotopic analyses. Two new leaves of each plant were randomly collected on 8 July 2006 (dry season) and on 3 May 2007 (wet season). Only parts of leaves that had no contact with labelled debris and flies were analysed. The leaves were homogenized together and were dried at 60 °C, crushed to obtain a fine powder and this material was stored dry in polypropylene tubes until isotopic analyses.

Isotopic analyses

The 15N atoms percentage values and total nitrogen concentration (total N μg mg−1 dry leaf tissue) of the bromeliad leaves, the enriched faeces from spiders fed with enriched flies and enriched flies were determined with an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (20–20 mass spectrometer; PDZ Europa, Sandbach, UK) after sample combustion to N2 at 1000 °C by an on-line elemental analyser (PDZ Europa ANCA-GSL) in the Stable Isotope Facility at the University of California at Davis. To calculate the nitrogen fraction in the plants receiving faeces of P. chapoda and fly D.melanogaster (fA), the two-source (i.e. soil and faeces/flies) mixing model equations with a single isotopic signature (e.g. δ15N), described by Phillips and Gregg (2001), were used. Additionally, the 15N fractioning during its assimilation and the metabolic process of the plants was considered according to the following equation (McCutchan et al., 2003):

where fA is the proportionate contribution of labelled D. melanogaster or faeces of P. chapoda (%), δM is the isotope ratio of the plants that received faeces or flies, δA and δB are the isotope ratios of potential nitrogen sources (faeces/flies and soil, respectively) and Δδ15N is the trophic shift for nitrogen between diet (e.g. faeces, flies or soil) and consumer (e.g. bromeliads). The values of Δδ15N used were +3·3 ± 0·26 ‰ (mean ± s.e.) for the plants that received faeces and +1·4 ± 0·2 ‰ for the plants that received flies (McCutchan et al., 2003).

The nitrogen acquisition values were compared among bromeliad species and treatments (faeces and flies), and between seasons using ANOVA; Fisher's least square difference (LSD) post-hoc tests were used for pair-wise comparisons. For nitrogen acquisition comparisons between the two seasons, the data from the plants that received enriched flies were removed from the analysis because this treatment was only carried out during the wet season.

Analyses of plant pigments and protein

To determine if the nitrogen derived from P. chapoda had some influence on the physiology of host plants, bromeliads from the wet season experiment were analysed for concentrations of chlorophyll, carotenoid and soluble proteins. The leaves used in these analyses were different from those used in isotopic analysis. The procedures to obtain chlorophyll a, b, a + b and carotenoid contents were those of Lichtenthaler (1987). Six fresh leaves from the intermediate part of the rosettes were randomly chosen and cut in small pieces; 1 g was frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized with 7 mL of 80 % acetone. The extract was filtered using filter paper, which had been previously dampened with 2 mL of the same solvent, and the residue retained in the filter paper was washed three times with 4 mL of solvent. The combined filtered extracts were volume adjusted to 20 mL and the absorbance was measured with a spectrophotometer at 470 nm, 647 nm and 663 nm.

The soluble proteins were extracted from 1 g of leaf first cut into small pieces, frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized with 3 mL of ultra-pure water. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12 000 rpm (g) for 10 min and the supernatant (15 µL) was used to measure the protein concentration (Bradford, 1976). The absorbance was measured using a spectrophotometer at 595 nm and a standard curve was obtained with bovine serum albumin.

Data on the concentrations (μg g−1 fresh leaf mass) of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, chlorophyll a + b, carotenoids and soluble protein were log10 transformed and then compared among treatments (faeces, flies and controls) and bromeliad species using two-way ANOVA.

Bromeliad growth

To test if the nitrogen derived from spiders affected plant growth and whether growth varied seasonally, two new leaves from each experimental plant were randomly chosen and their lengths were measured at the beginning and at the end of the experiments. A previous study showed that leaf length is the best growth measure for bromeliads having hard and narrow leaves (see Romero et al., 2006). Since leaf removal would affect plant growth, no other measurements such as leaf biomass were taken. Actually, significant linear regressions have been detected between leaf length and its dry biomass before this study (B. balansae: r2 = 0·84, P < 0·001; An. comosus: r2 = 0·88, P < 0·001; Ae. distichantha: r2 = 0·80, P < 0·001). The relative growth rate (RGR) was calculated from these data in both experimental seasons using the following equation:

in which ln(Lfinal) and ln(Linitial) are, respectively, the natural logarithm of the foliar final length and the natural logarithm of the foliar initial length, with t2 – t1 being the time in days between the initial and final measurements. The RGR values obtained were compared among treatments, bromeliad species and between seasons using a two- or three-way ANOVA; Fisher's LSD post-hoc tests were used for pair-wise comparisons. For RGR comparisons between the two experimental seasons, the data from the plants that received enriched flies were removed from the analysis.

RESULTS

Nitrogen flux from spiders to bromeliads

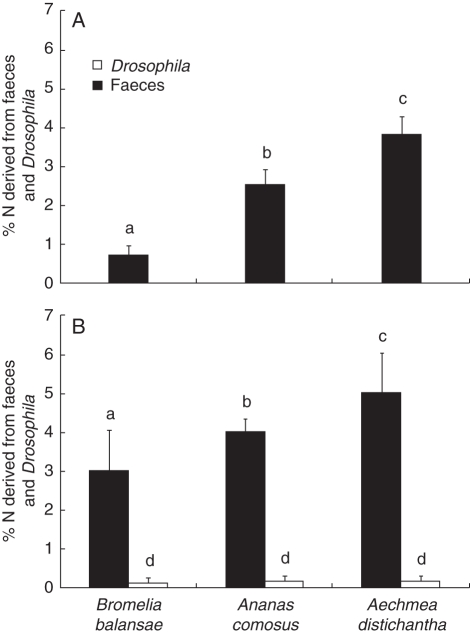

The δ15N values of enriched flies, of P. chapoda spiders that fed on the enriched flies and of spider faeces indicate that these materials were enriched in the experiments during the dry and wet seasons (Table 1). Psecas chapoda contributed nutritionally to the host plants B. balansae, An. comosus and Ae. distichantha (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the nitrogen derived from P. chapoda faeces was absorbed in different proportions among the three bromeliads (Table 2); B. balansae and Ae. distichantha derived less and more nitrogen from P. chapoda, respectively (Fig. 1) and its absorption was greater in the wet than in the dry season (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Whereas P. chapoda contributed from 0·6 ± 0·2 % (mean ± s.e.; dry season) to 2·7 ± 1 % (wet season) of the total nitrogen of B. balansae, it contributed from 2·4 ± 0·4 % (dry) to 4·1 ± 0·3 % (wet) of the total nitrogen of An. comosus and from 3·8 ± 0·4 % (dry) to 5 ± 1 % (wet) of the total nitrogen contributed to Ae. distichantha (Fig. 1A, B). The nitrogen derived from D. melanogaster flies was lower than those derived from spider faeces, and did not differ among the bromeliad species (Table 2 and Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

Average δ15N values of (A) natural abundance and enriched spiders, spider faeces and Drosophila flies in the dry and wet seasons, and of (B) Bromelia balansae, Aechmea distichantha and Ananas comosus leaves that received enriched faeces and Drosophila flies, and control, during the dry (May to July 2006 ) and wet seasons (March to April 2007)

| Treatment | δ15N values (s.e.) | n |

|---|---|---|

| (A) | ||

| Dry season | ||

| Faeces | ||

| Natural abundance | 12·10 (2·71) | 3 |

| Enriched | 3054·41 (151·55) | 4 |

| Drosophila melanogaster | ||

| Natural abundance | 3·07 (0·19) | 2 |

| Enriched | 3027·61 (173·52) | 5 |

| Spider (adult female) | ||

| Natural abundance | 17·08 | 1 |

| Enriched | 2108·11 (384·48) | 4 |

| Wet season | ||

| Faeces | ||

| Natural abundance | 12·1 (2·71) | 3 |

| Enriched | 1797·21 (63·09) | 5 |

| Drosophila melanogaster | ||

| Natural abundance | 3·07 (0·19) | 2 |

| Enriched | 2366·79 (40·16) | 5 |

| Spider (adult female) | ||

| Natural abundance | 17·08 | 1 |

| Enriched | 1215·99 (253·11) | 5 |

| (B) | ||

| Dry season | ||

| B. balansae | ||

| Faeces | 23·28 (7·27) | 5 |

| Control | 1·84 (1·21) | 5 |

| An. comosus | ||

| Faeces | 78·56 (11·64) | 5 |

| Control | 1·71 (1·71) | 4 |

| Ae. distichantha | ||

| Faeces | 117·91 (12·43) | 5 |

| Control | –1·03 (1·47) | 5 |

| Wet season | ||

| B. balansae | ||

| Faeces | 59·62 (18·28) | 5 |

| Flies | 8·84 (2·84) | 5 |

| Control | 6·66 (1·46) | 5 |

| An. comosus | ||

| Faeces | 82·90 (4·72) | 5 |

| Flies | 13·69 (2·58) | 5 |

| Control | 5·19 (2·17) | 5 |

| Ae. distichantha | ||

| Faeces | 108·71 (17·53) | 5 |

| Flies | 17·86 (2·85) | 5 |

| Control | 14·57 (1·47) | 5 |

The standard errors of means are in parenthesis.

n, Number of replicates.

Fig. 1.

The percentage of nitrogen in Bromelia balansae, Ananas comosus and Aechmea distichantha derived from Psecas chapoda faeces and Drosophila melanogaster flies during the (A) dry- (May to July, 2006) and (B) wet- (March to April, 2007) season experiments. In the dry-season experiment no flies were used. Values were obtained from the two-source mixing models equations (see Materials and Methods for details). Bars indicate the s.e. and letters indicate post-hoc comparisons by Fisher's LSD (α < 0·05).

Table 2.

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) comparing the amount of nitrogen of the bromeliad species Bromelia balansae, Ananas comosus and Aechmea distichantha that was derived from Psecas chapoda faeces and Drosophila melanogaster flies (treatments) in different seasons (dry: May to July 2006; wet: March to April 2007). Significance of P < 0·05 is highlighted in bold

| Source of variation | d.f. | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparing treatments (only for wet season) | ||||

| Treatments | 1 | 100·8 | 58·90 | <0·001 |

| Bromeliads | 2 | 3·929 | 2·089 | <0·001 |

| Treatments × bromeliads | 2 | 3·422 | 1·820 | 0·1838 |

| Error | 24 | 1·881 | ||

| Comparing seasons (only for treatment ‘faeces’) | ||||

| Seasons | 1 | 20·83 | 16·78 | <0·001 |

| Bromeliads | 1 | 19·08 | 15·36 | <0·001 |

| Seasons × bromeliads | 2 | 0·5083 | 0·4094 | 0·6686 |

| Error | 24 | 1·242 | ||

Plant pigments and protein

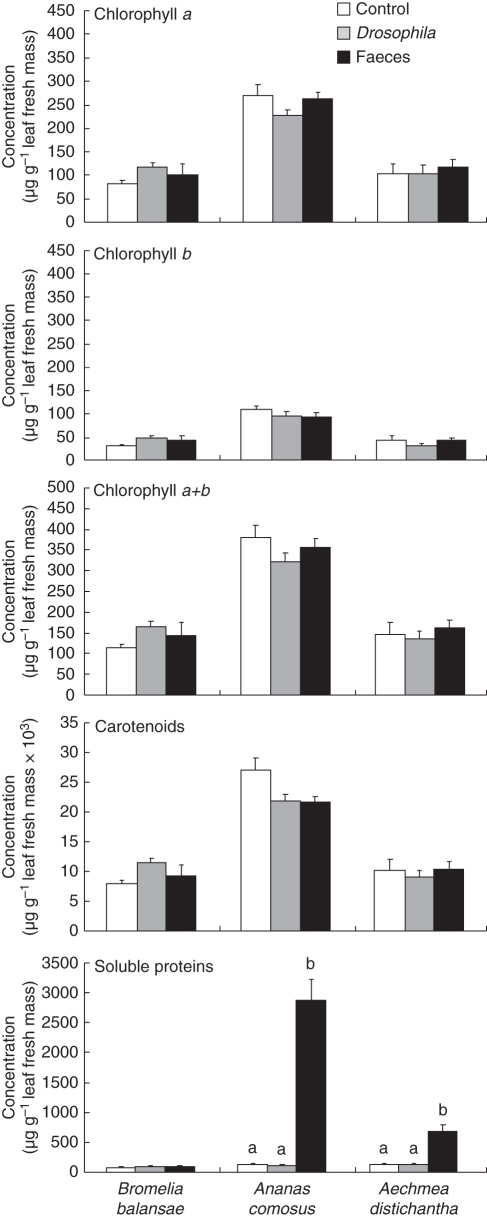

Chlorophyll and carotenoid concentrations in B. balansae, An. comosus and Ae. distichantha did not differ among treatments (Table 3 and Fig. 2). Chlorophylls and carotenoids differed among bromeliad species (Table 3); whereas An. comosus had the highest concentrations of chlorophylls and carotenoids, B. balansae and Ae. distichantha shared similar concentrations (Fig. 2). In contrast to pigments, significant differences were found for soluble proteins among treatments, bromeliad species and their interactions (Table 3). Ananas comosus and Ae. distichantha showed increased protein concentrations when they received spider faeces with the highest concentrations in An. comosus (Fig. 2).

Table 3.

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) summarizing the effects of different treatments (Psecas chapoda faeces, Drosophila melanogaster flies and control) on chlorophylls a, b, a + b, carotenoids and soluble proteins concentrations in Bromelia balansae, Ananas comosus and Aechmea distichantha, in the wet-season experiment. Significance of P < 0·05 is highlighted in bold

| Source of variation | d.f. | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll a | ||||

| Treatments | 2 | 0·0070 | 0·37 | 0·69 |

| Bromeliads | 2 | 0·8377 | 44·82 | <0·001 |

| Treatments × bromeliads | 4 | 0·0214 | 1·14 | 0·351 |

| Error | 36 | 0·0187 | ||

| Chlorophyll b | ||||

| Treatments | 2 | 0·0003 | 0·016 | 0·984 |

| Bromeliads | 2 | 0·8091 | 48·28 | <0·001 |

| Treatments × bromeliads | 4 | 0·0314 | 1·87 | 0·136 |

| Error | 36 | 0·0168 | ||

| Chlorophyll a + b | ||||

| Treatments | 2 | 0·0044 | 0·25 | 0·779 |

| Bromeliads | 2 | 0·8282 | 47·18 | <0·001 |

| Treatments × bromeliads | 4 | 0·0219 | 1·25 | 0·308 |

| Error | 36 | 0·0176 | ||

| Carotenoids | ||||

| Treatments | 2 | 0·0023 | 0·16 | 0·852 |

| Bromeliads | 2 | 0·7997 | 55·78 | <0·001 |

| Treatments × bromeliads | 4 | 0·0271 | 1·89 | 0·133 |

| Error | 36 | 0·0143 | ||

| Soluble proteins | ||||

| Treatments | 2 | 1·6728 | 70·38 | <0·001 |

| Bromeliads | 2 | 2·6749 | 112·54 | <0·001 |

| Treatments × bromeliads | 4 | 0·7921 | 33·32 | <0·001 |

| Error | 36 | 0·0238 | ||

Fig. 2.

Chlorophylls a, b, a + b, carotenoids and soluble protein concentrations for Bromelia balansae, Ananas comosus and Aechmea distichantha during treatments with Psecas chapoda faeces, Drosophila melanogaster flies and control, as indicated, in the wet season experiment. Bars indicate the s.e. Letters indicate post-hoc comparisons by Fisher's LSD (α < 0·05) and their absence indicates no statistical differences among treatments. Species were analysed separately.

Bromeliad growth

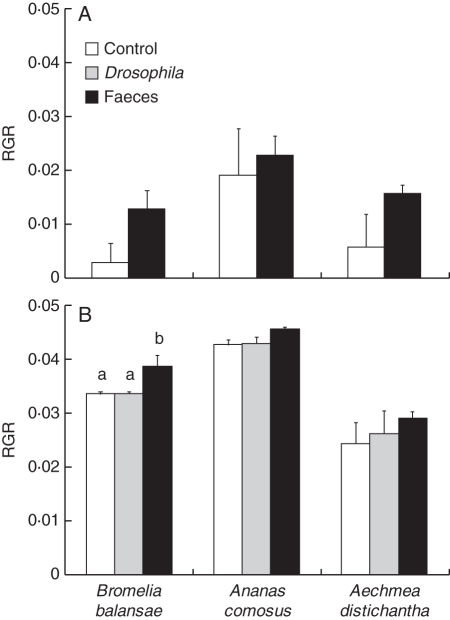

Whereas the addition of faeces in the dry season only marginally affected the growth (RGR) of the bromeliads (P = 0·052), the addition of faeces or flies during the wet season improved plant growth (P = 0·046; Table 4 and Fig. 3A, B). In this season the bromeliads receiving faeces grew more; however, this difference was mainly observed because of the response of B. balansae to the different treatments (Fig. 3B). While B. balansae grew more when receiving faeces, the RGR of the other species were not affected by faeces addition (Fig. 3B). Moreover, faeces contributed more than flies to B. balansae growth (Fig. 3B).

Table 4.

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) summarizing the effects of different treatments (Psecas chapoda faeces, Drosophila melanogaster flies and control) on the foliar growth rate (RGR) of Bromelia balansae, Ananas comosus and Aechmea distichantha, during the dry (May to July 2006) and wet seasons (March to April 2007). Significance of P<0·05 is highlighted in bold

| Source of variation | d.f. | MS | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry season | ||||

| Treatments | 1 | 0·00044 | 4·12 | 0·052 |

| Bromeliads | 2 | 0·00044 | 4·15 | 0·028 |

| Treatments × bromeliads | 2 | 0·00003 | 0·31 | 0·738 |

| Error | 23 | |||

| Wet season | ||||

| Treatments | 2 | 0·00008 | 3·34 | 0·046 |

| Bromeliads | 2 | 0·00113 | 46·98 | <0·001 |

| Treatments × bromeliads | 4 | 0·000004 | 0·15 | 0·960 |

| Error | 36 | |||

| Comparing periods (only for treatment ‘faeces’) | ||||

| Periods | 1 | 0·0074 | 120·02 | <0·001 |

| Treatments (faeces vs. control) | 1 | 0·0005 | 8·80 | 0·005 |

| Bromeliads | 2 | 0·0010 | 16·40 | <0·001 |

| Periods × treatments | 1 | 0·00004 | 0·72 | 0·398 |

| Periods × bromeliads | 2 | 0·0001 | 3·08 | 0·055 |

| Treatments × bromeliads | 2 | 0·00002 | 0·478 | 0·627 |

| Periods × treatments × bromeliads | 2 | 0·000008 | 0·130 | 0·878 |

| Error | 47 | 0·00006 | ||

Fig. 3.

Relative growth rate (RGR) of the leaves of Bromelia balansae, Ananas comosus and Aechmea distichantha from different treatments (Psecas chapoda faeces, Drosophila melanogaster flies and control) during the (A) dry- (May to July, 2006) and (B) wet- (March to April, 2007) season experiments. Bars indicate the s.e. Letters indicate post-hoc comparisons by Fisher's LSD (α < 0·05) and their absence indicate no statistical differences among treatments. Species were analysed separately.

In the dry season, the RGR differed among the three bromeliad species (P = 0·028; Table 4) and it was higher in An. comosus, followed by Ae. distichantha and B. balansae (Fig. 3A; Fisher's LSD, An. comosus vs. B. balansae: P = 0·010; An. comosus vs. Ae. distichantha: P = 0·036; B. balansae vs. Ae. distichantha: P = 0·546). In the wet season, the RGR also differed significantly among the three bromeliad species (P < 0·001; Table 4). Nevertheless, An. comosus had greater growth, followed by B. balansae and Ae. distichantha (Fig. 3B; Fisher's LSD, An. comosus vs. B. balansae: P < 0·001; An. comosus vs. Ae. distichantha: P < 0·001; B. balansae vs. Ae. distichantha: P < 0·001). All bromeliads grew more during the wet than in the dry season (Table 4 and Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

The results indicate that P. chapoda spiders contribute to the nutrition of their three bromeliad hosts, B. balansae, An. comosus and Ae. distichantha, by nitrogen provisioning through their faeces. Therefore, the by-product mutualism between the spider P. chapoda and the plant B. balansae described recently by Romero et al. (2006, 2008b) can be extended to other host bromeliad species, such as Ae. distichantha and An. comosus. The three host plants of P. chapoda typically grow in poor soils due to high rates of weathering and leaching, or even in the outcrops of granitic rocks and in plant trunks (Romero, 2006; Romero et al., 2007), where the availability of nutrients is very low (Benzing, 2000; Press et al., 2006). Thus, the nitrogen derived from spiders seems to be of great benefit for these bromeliads. Since diverse spider species live associated with several other Bromelioideae species in various geographical regions (see Romero, 2006), we suggest that this type of digestive by-product mutualism extends to other spider–bromeliad systems.

The two CAM plants (Ae. distichantha and An. comosus) absorbed more nitrogen than the C3 bromeliad (B. balansae) in both the dry and wet seasons. Crassulacean acid metabolism can confer a higher efficiency of water use to these CAM plants even under severe hydric conditions (Martin, 1994). However, even the CAM plants showed a reduction in foliar nitrogen absorption and growth in the dry season compared with the wet season. Therefore, although CAM plants may be able to use the available water supply better, environmental harsh conditions (e.g. reduced humidity and temperature) may limit their performance. Griffiths et al. (1989) showed that the photosynthetic parameters of the CAM bromeliad Tillandsia flexuosa were substantially reduced during the dry season. In the wet season, greater water availability and higher temperatures also favour CAM plant growth and nitrogen absorption (Griffiths, 1988). In addition, greater environmental humidity can increase the contact of nutrients with trichome surfaces, improving trichome nutrient absorption (Benzing, 2000).

Aechmea distichantha was the species that absorbed the greatest amount of nitrogen derived from spider faeces, probably because it has poorly developed roots (Benzing, 1986) and larger, higher developed epidermic trichomes than B. balansae and An. comosus (Martin, 1994). Since Ae. distichantha inhabits rocky inselbergs (Romero, 2006), this species might depend more on animal detritus for its nutrition, absorbing nutrients via its leaves. Many authors (Benzing, 1986, 2000; Romero et al., 2006, 2008b, 2010) have suggested that epiphytic tank-bromeliads can benefit more from animal association than can terrestrial bromeliads. Terrestrial bromeliads appear to have plesiomorphic traits (i.e. C3 photosynthetic pathway, developed roots and fewer epidermic trichomes), while epiphytic and atmospheric bromeliads appear to have apomorphic traits (i.e. phytotelmata, developed trichomes) that allowed their adaptive distribution through oligotrophic environments (Medina, 1974; Benzing, 1986, 2000; Crayn et al., 2004). Biotic and abiotic factors, such as oligotrophy and leaf traits, affect a plant's nutritional options regarding the use of fauna for trophic advantage (Benzing, 1986, 2000; Armbruster et al., 2002; Leroy et al., 2009). Since Ae. distichantha has apomorphic leaf traits and occurs in oligotrophic environments, this species uses spiders for trophic advantage.

The C3 plant B. balansae and the epiphytic CAM plant Ae. distichantha differed only marginally in their growth in the dry season. In contrast, in the wet season B. balansae grew better but did not accumulate protein, while Ae. distichantha grew less and had increased soluble protein content. Soluble proteins are one of the main forms of store nitrogen in plants (Frommer et al., 1994) and their increase can reflect a plant's good nutritional status (Barneix and Causin, 1996). Whereas B. balansae may be allocating nitrogen derived from spiders to vegetative growth and clonal reproduction, the CAM plant may be allocating nitrogen to other ends (i.e. storage, reproduction and metabolism). In a greenhouse experiment, Benzing (1983) reported that, even with added fertilizer, epiphytic bromeliads did not significantly increase in size, suggesting that these plants have a slow growth rate associated with an adaptive response to survive in extremely oligotrophic environments. Nutrients absorbed by Ae. distichantha are apparently stored for nutritional stress conditions. The terrestrial bromeliad B. balansae, on the other hand, may be adapted to a less-limited environment which could explain the lower accumulation of soluble proteins compared with Ae. distichantha. Although B. balansae has trichomes which absorb more than the CAM plant An. comosus has (Benzing and Burt, 1970), the latter absorbed more nitrogen and also had the highest concentration of chlorophylls, carotenoids and soluble proteins. This probably occurred because An. comosus is a fast-growing species and has a high demand for nitrogen (Endres and Mercier, 2001). Although few studies have investigated the efficiency of nitrogen uptake in CAM bromeliads, they are possibly more capable of using available nitrogen from a variety of sources in the environment than C3 plants (Oaks, 1994; Kerbauy, 2004).

Both C3 and CAM plants were affected by the dry season conditions indicating that under field conditions the benefits of this spider–plant mutualism may be limited to certain periods of the year, i.e. it is seasonally restricted. When mutualism is considered from a cost-and-benefit perspective, it becomes clear that outcomes must in fact be extremely dynamic in space and time, along a continuum of possible outcomes (Bronstein, 1994). A great number of factors have been shown to influence these outcomes, especially the biotic and abiotic factors at the site in which the interaction takes place (Thompson, 1988; Bronstein, 1994). For example, in the interaction between Roridula plants and their mutualistic hemipteran Pameridea, Anderson and Midgley (2007) showed that plants had negative growth rates with no hemipterans, positive growth rates with intermediate hemipteran densities and negative growth rate with very high hemipteran densities. This research shows that mutualisms are a dynamic process which has variable outcomes. In the case of bromeliads and P. chapoda, bromeliads probably have benefit mainly in the rainy period of the year, even if they are inhabited by spiders during all seasonal periods (see Romero and Vasconcellos-Neto, 2005c). These results could be associated with abiotic factors like temperature and quantity of rainwater, since in the rainy season these factors do not limit plant growth. Recently, Romero et al. (2008b) showed that this system is also spatially restricted, i.e. bromeliads in areas where spiders are found in greater abundance derive more 15N than in areas where spiders are found in low density. Although few studies have investigated conditionality in spider–plant mutualistic systems, a knowledge of spatial and temporal conditional outcomes may be relevant for a better understanding of the evolution of these types of interactions.

In contrast, the three studied bromeliads absorbed very little nitrogen from D. melanogaster flies (simulating insects that eventually fall in the rosettes) compared with P. chapoda faeces (i.e. guanine; see Romero et al., 2006). A similar event was described by Ellis and Midgley (1996) and Anderson and Midgley (2002) for the digestive mutualism between the Pameridea roridulae hemiptera and its Roridula gorgonias host plant. Feeding on insects, P. chapoda spiders channel organic matter into the bromeliad rosettes and even excrete simple compounds (e.g. guanine) that can be directly absorbed by the plant's trichomes. On the other hand, insect chitin needs to be mineralized by bacteria and/or other microorganisms before it becomes available. Even Ae. distichantha, which has a tank and, therefore, would be expected to derive more nitrogen from insect carcasses (see Romero et al., 2006), had similar nitrogen obtention to the other species that were studied. These results reinforce the beneficial role of predators for epyphitic tank plants.

In conclusion, P. chapoda improved the performance and/or growth of their three host bromeliads. However, their effects varied temporally generating a conditional outcome in this digestive mutualistic event. There was a strong interspecific variation in nutrient uptake, which is probably related to each species' performance and photosynthetic pathways, i.e. CAM plants absorbed more nitrogen than the C3 bromeliad in both dry and wet seasons, but even the CAM plants reduced nitrogen uptake and growth in the dry season.Whereas B. balansae seems to use nitrogen for growth, Ae. distichantha apparently stores nitrogen for stressful nutritional conditions. Additionally, bromeliads absorbed more nitrogen coming from spider faeces than from flies, reinforcing the beneficial role played by predators in these digestive mutualisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Drs Aaron M. Ellison and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions on the manuscript, and Donald L. Phillips and Jonathan Moran for their help with the mixing models equations. Camila A. Cambuí helped with the physiological analyses and Ben Hur Gonçalves helped with mixing models equations. A.Z. Gonçalves was supported by an undergraduate fellowship from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP; 07/57300-5); G. Q. Romero was supported by research grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP; 04/13658-5 and 05/51421-0).

LITERATURE CITED

- Anderson B, Midgley JJ. It takes two to tango but three is a tangle: mutualists and cheaters on the carnivorous plant Roridula. Oecologia. 2002;132:369–373. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-0998-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B, Midgley JJ. Digestive mutualism, an alternate pathway in plant carnivory. Oikos. 2003;102:221–224. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B, Midgley JJ. Density-dependent outcomes in a digestive mutualism between carnivorous Roridula plants and their associated hemipterans. Oecologia. 2007;152:115–120. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster P, Hutchinson RA, Cotgreave P. Factors influencing community structure in a South American tank bromeliad fauna. Oikos. 2002;96:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Barneix AJ, Causin HF. The central role of amino acids on nitrogen utilization and plant growth. Journal of Plant Physiology. 1996;149:358–362. [Google Scholar]

- Benzing DH. Vascular epiphytes: a survey with special reference to their interactions with other organisms. In: Sutton SL, Whitmor TC, Chadwick AC, editors. Tropical rain forest: ecology and management. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1983. pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Benzing DH. Foliar specializations for animal-assisted nutrition in Bromeliaceae. In: Juniper B, Southwood R, editors. Insects and the plant surface. London: Edward Arnold; 1986. pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Benzing DH. Bromeliaceae: profile of an adaptive radiation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Benzing DH, Burt KM. Foliar permeability among twenty species of the Bromeliaceae. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. 1970;5:269–279. [Google Scholar]

- Borgo M, Silva SM. Epífitos vasculares em fragmentos de Floresta Ombrófila Mista, Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Botânica. 2003;3:391–401. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. Rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein JL. Conditional outcomes in mutualistic interactions. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1994;9:214–217. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crayn DM, Winter K, Smith JAC. Multiple origins of crassulacean acid metabolism and the epiphytic habit in the Neotropical family Bromeliaceae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA. 2004;101:3703–3708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400366101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis AG, Midgley JJ. A new plant–animal mutualism involving a plant with sticky leaves and a resident hemipteran insect. Oecologia. 1996;106:478–481. doi: 10.1007/BF00329705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres L, Mercier H. Influence of nitrogen forms of the growth and nitrogen metabolism of bromeliads. Journal of Plant Nutrition. 2001;24:29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer RC, Wanek W, Richter A, Mayer V. Do ants feed plants? A 15N labeling study of nitrogen fluxes from ants to plants in the mutualism of Pheidole and Piper. Journal of Ecology. 2003;91:126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Frommer WB, Kwart M, Hirner B, Fischer WN, Hummel S, Ninnemann O. Transporters for nitrogenous compounds in plants. Plant Molecular Biology. 1994;26:1651–1670. doi: 10.1007/BF00016495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves-Souza T, Omena PM, Souza JC, Romero GQ. Trait-mediated effects on flowers: artificial spiders deceive pollinators and decrease plant fitness. Ecology. 2008;89:2407–2413. doi: 10.1890/07-1881.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths H. Carbon balance during CAM: an assessment of respiratory CO2 recycling in the epiphytic bromeliads Aechmea nudicaulis and Aechmea fendleri. Plant, Cell & Environment. 1988;11:603–611. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths H, Lüttge U, Popp M, et al. Ecophysiology of xerophytic and halophytic vegetation of a coastal alluvial plain in northern Venezuela. IV. Tillandsia flexuosa Sw. and Schomburgkia humboldtiana Reichb., epiphytic CAM plants. New Phytologist. 1989;111:273–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1989.tb00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez MO, Lavin MC, Ayala FC, Perez AJ. Arthropods associated with Bromelia hemisphaerica (Bromeliales: Bromeliaceae) in Morelos, Mexico. Florida Entomologist. 1993;76:616–621. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera CM, Pellmyr O. Plant–animal interactions: an evolutionary approach. Boston, MA: Blackwell Science; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- INPE/CPTEC. Centro de previsão de tempo e estudos climáticos. 2008 available at http://www.cptec.inpe.br . [Google Scholar]

- Inselsbacher E, Cambui CA, Richter A, Stange CF, Mercier H. Microbial activities and foliar uptake of nitrogen in the epiphytic bromeliad Vriesea gigantea. New Phytologist. 2007;175:311–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerbauy GB. Fisiologia vegetal. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Guanabara Koogan S.A; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Knight TM, Chase JM, Hillebrand H, Holt RD. Predation on mutualists can reduce the strength of trophic cascades. Ecology Letters. 2006;9:1173–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy C, Corbara B, Dejean A, Céréghino R. Ants mediate foliar structure and nitrogen acquisition in a tank-bromeliad. New Phytologist. 2009;183:1124–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler HK. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods in Enzymology. 1987;148:350–382. [Google Scholar]

- McCutchan JHJ, Lewis WMJ, Kendall C, McGrath CC. Variation in trophic shift for stable isotope ratios of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur. Oikos. 2003;102:378–390. [Google Scholar]

- Machado G, Oliveira PS. Maternal care in the neotropical harvestman Bourguyia albiornata (Arachnida: Opiliones): oviposition site selection and egg protection. Behaviour. 2002;139:1509–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Martin CE. Physiological ecology of the Bromeliaceae. The Botanical Review. 1994;1:1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Medina E. Dark CO2 fixation, habitat preference and evolution within the Bromeliaceae. Evolution. 1974;28:677–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1974.tb00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oaks A. Efficiency of nitrogen utilization in C3 and C4 cereals. Plant Physiology. 1994;106:407–414. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.2.407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omena PM, Romero GQ. Fine-scale microhabitat selection in a bromeliad-dwelling jumping spider (Salticidae) Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2008;94:653–662. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DL, Gregg JW. Uncertainty in source partitioning using stable isotopes. Oecologia. 2001;127:171–179. doi: 10.1007/s004420000578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Press F, Siever R, Grotzinger J, Jordan TH. Para entender a terra. Porto Alegre: Bookman Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rico-Gray V, Oliveira PS. The ecology and evolution of ant–plant interactions. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Romero GQ. Geographic range, habitats and host plants of bromeliad-living jumping spiders (Salticidae) Biotropica. 2006;38:522–530. [Google Scholar]

- Romero GQ, Vasconcellos-Neto J. The effects of plant structure on the spatial and microspatial distribution of a bromeliad-living jumping spider (Salticidae) Journal of Animal Ecology. 2005a;74:12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Romero GQ, Vasconcellos-Neto J. Spatial distribution and microhabitat preference of Psecas chapoda (Peckham & Peckham) (Araneae, Salticidae) The Journal of Arachnology. 2005b;33:124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Romero GQ, Vasconcellos-Neto J. Population dynamics, age structure and sex ratio of the bromeliad-dwelling jumping spider, Psecas chapoda (Salticidae) Journal of Natural History. 2005c;39:153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Romero GQ, Mazzafera P, Vasconcellos-Neto J, Trivelin PCO. Bromeliad-living spiders improve host plant nutrition and growth. Ecology. 2006;87:803–808. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[803:bsihpn]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero GQ, Santos AJ, Wienskoski EH, Vasconcellos-Neto J. Association of two new Coryphasia species (Araneae, Salticidae) with tank-bromeliads in southeastern Brazil: habitats and patterns of host plant use. The Journal of Arachnology. 2007;35:181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Romero GQ, Souza JC, Vasconcellos-Neto J. Anti-herbivore protection by mutualistic spiders and the role of plant glandular trichomes. Ecology. 2008a;89:3105–3115. doi: 10.1890/08-0267.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero GQ, Vasconcellos-Neto J, Trivelin PCO. Spatial variation in the strength of mutualism between a jumping spider and a terrestrial bromeliad: evidence from the stable isotope 15N. Acta Oecologica. 2008b;33:380–386. [Google Scholar]

- Romero GQ, Nomura F, Gonçalves AZ, et al. Nitrogen fluxes from treefrogs to tank epiphytic bromeliads: an isotopic and physiological approach. Oecologia. 2010;162:941–949. doi: 10.1007/s00442-009-1533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagers CL, Ginger SM, Evans RD. Carbon and nitrogen isotopes trace nutrient exchange in an ant–plant mutualism. Oecologia. 2000;123:582–586. doi: 10.1007/PL00008863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solano PJ, Dejean A. Ant-fed plants: comparison between three geophytic myrmecophytes. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2004;83:433–439. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JN. Variation in interspecific interactions. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1988;19:65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Treseder KK, Davidson DW, Ehleringer JR. Absorption of ant-provided carbon and nitrogen by a tropical epiphyte. Nature. 1995;357:137–139. [Google Scholar]