Abstract

Objective: The majority of first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients reach clinical remission; however, rates of relapse are high. This study sought to undertake a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to determine the effectiveness of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to prevent relapse in FEP patients. Methods: Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Results: Of 66 studies retrieved, 18 were eligible for inclusion. Nine studies investigated psychosocial interventions and 9 pharmacological treatments. The analysis of 3 RCTs of psychosocial interventions comparing specialist FEP programs vs treatment as usual involving 679 patients demonstrated the former to be more effective in preventing relapse (odds ratio [OR] = 1.80, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.31–2.48; P < .001; number needed to treat [NNT] = 10). While the analysis of 3 different cognitive-behavioral studies not specifically intended at preventing relapse showed no further benefits compared with specialist FEP programs (OR = 1.95, 95% CI = 0.76–5.00; P = .17), the combination of specific individual and family intervention targeted at relapse prevention may further improve upon these outcomes (OR = 4.88, 95% CI = 0.97–24.60; P = .06). Only 3 small studies compared first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) with placebo with no significant differences regarding relapse prevention although all individual estimates favored FGAs (OR = 2.82, 95% CI = 0.54–14.75; P = .22). Exploratory analysis involving 1055 FEP patients revealed that relapse rates were significantly lower with second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) compared with FGAs (OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.07–2.01; P < .02; NNT = 10). Conclusions: Specialist FEP programs are effective in preventing relapse. Cognitive-based individual and family interventions may need to specifically target relapse to obtain relapse prevention benefits that extend beyond those provided by specialist FEP programs. Overall, the available data suggest that FGAs and SGAs have the potential to reduce relapse rates. Future trials should examine the effectiveness of placebo vs antipsychotics in combination with intensive psychosocial interventions in preventing relapse in the early course of psychosis. Further studies should identify those patients who may not need antipsychotic medication to be able to recover from psychosis.

Keywords: first-episode psychosis, relapse prevention, cognitive-behavioral therapy, antipsychotic treatment

Introduction

Antipsychotic medication is associated with rapid improvement of positive psychotic symptoms in the majority of first-episode psychosis (FEP) patients.1–3 Indeed, previous research indicates that up to 96% of FEP patients reach clinical remission within 12 months of treatment commencement.4–6 Unfortunately, the prognosis for young patients with psychosis is less encouraging over the longer term following their initial response to acute treatment. Naturalistic long-term follow-up studies have shown that the early course of psychosis is characterized by repeated relapses, and up to 80% of FEP patients experience a relapse within 5-year remission from the initial episode.4,5,7,8 This is significant because with each subsequent relapse the risk of developing persistent psychotic symptoms increases.8,9 Recurrent psychotic episodes are associated with progressive loss of gray matter that may reduce the effectiveness of antipsychotic medications.10 Moreover, relapse is likely to interfere with the social and vocational development of young people suffering from psychosis, which may have an impact on long-term outcomes.11 Finally, economic analyses have indicated that the cost for treatment of relapsing psychosis is 4 times that of stable psychosis.12,13

It is, therefore, not surprising that reducing the number of relapses is a major goal of interventions for FEP.3,4 Early psychosis treatment guidelines include the development of an active relapse prevention plan as one of the major aspects of early intervention.14–16 However, current FEP guidelines are mostly consensus based, not evidence based.11 A rigorous review of the available evidence is overdue and essential to inform future guidelines on relapse prevention in early psychosis. The present study sought to undertake a systematic review and meta-analysis of all relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions to prevent relapse in FEP patients.

Methods

Search Strategy

Systematic bibliographic searches employing Cochrane methodology were performed to find relevant English and non-English language trials from the following databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Medline, Medline Unindexed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, UMI Proquest Digital Dissertations, Information Science Citation Index Expanded, Information Social Sciences Citation Index, and Information Arts and Humanities Citation Index with each database being searched from inception to December 2008. We additionally searched conference abstracts from ISI Science and Technology proceedings and ISI Information Social Science and Humanities proceedings. Electronic searches were supplemented by hand searching reference lists of retrieved trials, previous reviews, and abstracts from meetings. Finally, trialists and other experts were contacted for unpublished studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Considered for inclusion were RCTs of pharmacological or nonpharmacological interventions that comprised at least 75% of participants experiencing their FEP diagnosed using either Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or International Classification of Drugs criteria. Broad definitions of a FEP were considered including the following diagnostic categories: schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, substance-induced psychotic disorder, and psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. Two types of trials were considered, (1) those where the a priori aim was to test interventions to prevent relapse in clinically stable or remitted FEP patients and (2) those where randomization was performed during the acute phase, and relapse rates were determined by follow-up of those who responded to acute treatment. Comparison interventions could include standard care, placebo, or an active comparator intervention. Trials were excluded if they had a follow-up period shorter than 6 months, as these were not considered to be adequate for an assessment of relapse prevention.17 Two reviewers (M.Á.-J. and S.E.H.) independently assessed all potentially relevant articles for inclusion. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. It was necessary in 2 cases18,19 to contact the trial authors to determine eligibility.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was the number of relapses, with secondary outcome measures including mean hospital days, time to relapse, duration of second episode, and discontinuation of treatment due to adverse events. Relapse was defined according to the criteria used in the individual studies. Specifically, relapse was defined either “as stated by the authors” when trials employed prespecified relapse criteria or “as admission to hospital” when relapse was defined as rehospitalizations due to an exacerbation of psychotic symptoms. Trial authors were contacted for the provision of missing data for the meta-analysis if necessary.

Data Extraction

Three reviewers (A.P, S.E.H., and M.Á.-J.) independently extracted relevant data from included trials, including the characteristics and nature of the intervention and comparison groups, definition of relapse and method of assessment, the clinical remission criteria employed, and information regarding the outcome parameters. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Assessment of Methodological Quality

Methodological quality was assessed via the Cochrane's Collaboration “risk of bias” tool.20 This measure is a 2-part tool that addresses 6 different domains of methodological quality, namely, sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other bias. Following Cochrane's recommendations, the assessment of the blinding domain focused on relevant outcome variables (ie, assessment of relapse, number of bed days, time to relapse). The “other bias” domain was assessed via the following criteria: (1) imbalance of baseline characteristics across study groups, (2) relapse measured according to prespecified criteria, and (3) relapse was measured prospectively. Three reviewers (M.Á.-J., S.E.H., and A.P.) independently assessed the methodological quality. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Statistical Analyses

Outcomes were pooled using Review Manager 5, meta-analytic standard software used by the Cochrane Collaboration.21 For dichotomous variables (ie, number of relapses, frequency of adverse events), combined risk ratios were estimated using a fixed-effect meta-analysis with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The number needed to treat (NNT) statistic, calculated as the reciprocal of the risk difference in relapse between 2 groups, was estimated in the case of significant results. For continuous variables (ie, number of bed days, time to relapse, duration of relapse), the weighted mean difference (WMD) was estimated using a fixed-effect meta-analysis.

Heterogeneity of intervention estimates was assessed by visually inspecting the overlap of CIs on the forest plots and by the I2 statistic. The I2 test of heterogeneity describes the proportion of total variation in study estimates that is due to heterogeneity.22 Given the heterogeneity of trials, random-effects meta-analysis was fitted. Random-effects models are, in general, more conservative than fixed-effects models because they take heterogeneity among studies into account.23 With decreasing heterogeneity, the random-effects approach moves asymptotically toward a fixed-effects model.

Studies with significant results are more likely to be published than those with nonsignificant or negative results.24 In order to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias, data from included trials were entered into a funnel graph (a scatterplot of treatment effect against a measure of study size).25 In the absence of bias, the plot should resemble a symmetrical inverted funnel.26 An asymmetric funnel indicates a relationship between treatment effect and study size. This suggests the possibility of either publication bias or a systematic difference between smaller and larger studies. Namely, if publication bias exists, it is expected that, of published studies, the largest ones will report the smallest effects.25 Finally, sensitivity analyses were performed in order to further assess the robustness of the findings to the choice of statistical method (fixed- or random-effects model) and measures of effect size (relative risks or odds ratios [ORs]).

Results

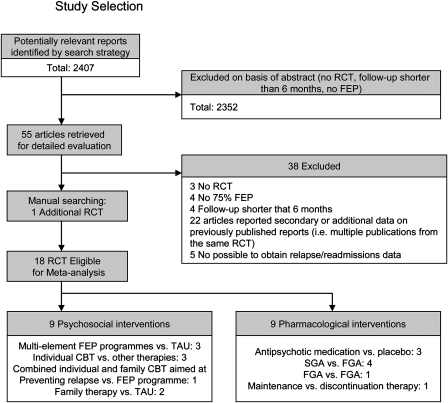

Of 55 studies retrieved, 18 were eligible for inclusion (figure 1). We excluded 3 studies that were nonrandomized,18,27,28 4 studies in which less than 75% of the sample were FEP patients,29–32 4 studies with a follow-up shorter than 6 months,33–36 and 2 long-term RCTs that did not report on relapse/readmissions, and the authors confirmed that further data were not available.37,38 Nine of the included studies investigated psychosocial interventions, and 9 examined pharmacological treatments. Psychosocial interventions included specialist FEP programs vs treatment as usual (TAU),39–41 cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT),42–44 and individual and family cognitive-based relapse prevention therapy45 and family therapy vs TAU.46,47 Trials of pharmacological interventions included those comparing antipsychotic medication with placebo,48–50 second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs),3,51–53 FGAs with FGAs,54 and treatment maintenance with discontinuation therapy.55

Fig. 1.

Study Selection.

Supplementary tables 1 and 2 depict the characteristics of the trials included in the meta-analysis. Eighteen trials involving 2707 participants were included. The participants’ mean age ranged from 21 to 32 years. Eight trials included clinically remitted FEP patients,40,44,45,47,49–51,55 and 10 followed responders from acute phase trials.3,39,41–43,46,48,52–54 Ten trials reported follow-up periods ranging from 7 months to 1 year,2,42,44–46,49–51,53,54 and 8 trials included follow-up periods of 18 months to 2 years.3,39–41,43,47,48,55 Regarding the assessment of relapse, 11 trials used prespecified relapse criteria (ie, relapse defined as stated by the authors),3,39,40,43,45,48–51,54,55 and 7 trials assessed relapse defined as the number of rehospitalizations due to an exacerbation of psychotic symptoms.41,42,44,46,47,52,53 Of those that included specific relapse criteria, 3 trials employed previously proposed criteria3,40,45 and 8 established their own criteria,39,43,48–51,54,55 although a significant exacerbation of positive symptoms and a marked social impairment were included in most definitions of relapse (Supplementary tables 1 and 2). Four trials reported data on time to relapse.3,45,51,55 Information on duration of relapse or hospital days was reported in 6 trials,39–42,45,51 and in 1 trial, we were able to use data on hospital days with the help of the authors.55 Data on discontinuation due to adverse events were provided by 5 trials.3,51–54 Ten trials were conducted in Europe39–41,43,46,48,50,51,54,55 (N = 1602), 2 in Asia47,52 (N = 247), 1 in the United States49 (N = 28), 3 in Australia42,44,45 (N = 172), and 2 trials were conducted in multiple countries3,53 (N = 920).

Psychosocial Interventions

Specialist FEP Programs Vs TAU.

Three trials involving 679 participants tested the effectiveness of specialist FEP programs vs TAU.39–41 FEP programs provided a comprehensive array of specialized and phase-orientated in- and outpatient services designed for FEP patients and emphasized both community-based treatment and functional recovery. Specifically, specialist programs comprised multidisciplinary teams with low caseloads that provided assertive outreach treatment and evidence-based interventions tailored to the needs of FEP patients including low-dose atypical antipsychotic regimens, manualized cognitive-behavioral strategies, individualized crisis management plans, as well as family counseling and psychoeducation.39–41 TAU consisted of the usual care provided by nonspecialist mental health services. Two trials reported on number of relapses as stated by the authors,39,40 and 1 provided data for relapse defined as admission to hospital.41 When these 3 trials were combined, there was no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0; P = .82), and the pooled OR was statistically significant in favor of the specialist FEP programs (OR = 1.80, 95% CI = 1.31–2.48; P < .001; figure 2). The overall estimated NNT for the specialized FEP programs to prevent one relapse was approximately 8.

Fig. 2.

Differences in Risk of Relapse in FEP Patients in Studies Comparing Specialist FEP Programs With TAU, Individual CBT, and Individual and Family RPT. FEP, first-episode psychosis; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; RPT, relapse prevention therapy; TAU, treatment as usual; M-H random, Mantel-Haenszel method random effects; CI, confidence interval. Note: event = number of relapses; weight = it is indicated by the size of the square on each graph line and is related to the number of participants and events in the study.

Subsequently, the number of hospital days for both the specialist FEP programs and TAU groups was analyzed. There was a statistically significant reduction in mean bed days for patients in the FEP programs compared with those on TAU (WMD = −26.20 d, 95% CI = −7.35 to −45.06 d; P < .01) with no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = .71).

Specialist FEP Programs Vs CBT.

Individual CBT

Three trials including 283 participants investigated the effectiveness of individual CBT vs other forms of therapy.42–44 One trial compared CBT with both supportive counseling and TAU,43 one examined the effectiveness of CBT compared with befriending plus specialist FEP program,42 and one trial evaluated a cannabis-focused intervention in addition to specialist FEP care compared with a specialist FEP program alone.42,44 One trial provided data on relapse as defined by the authors,43 whereas 2 evaluated relapse defined as admission to hospital.42,44 When those trials evaluating the effectiveness of CBT plus specialist FEP care vs an FEP specialist program were combined, the resulting pooled OR demonstrated no statistically significant advantages in favor of CBT (OR = 1.95, 95% CI = 0.76–5.00; P = .17) with no evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, P = .48; figure 2). Similarly, the evaluation of CBT compared with supportive counseling and TAU43 did not yield significant results in favor of CBT (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 0.63–1.95; P = .72; and OR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.65–2.04; P = .62; respectively).

Individual and Family Cognitive-Based Relapse Prevention Therapy

One trial that involved 81 participants compared the efficacy of the addition of an individual and family cognitive-based relapse prevention therapy with a specialist FEP program alone.45 This trial found a trend toward statistical significant superiority of the combined intervention for relapse as defined by the authors (reversed OR is provided for clarity purposes; OR = 4.88, 95% CI = 0.97–24.60; P = .06; figure 2).

Family Therapy Vs TAU

Two trials involving 184 participants compared family therapy with TAU.46,47 The pooled ORs were not statistically significant in favor of family therapy for relapse as defined by admission to hospital (OR = 2.82, 95% CI = 0.54–14.75; P = .22), although there was evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 76%, P < .05), and both estimates were in different directions.

Pharmacological Interventions

Antipsychotic Medication Vs Placebo.

Three trials, including 166 participants, examined the effectiveness of antipsychotic medication compared with placebo to prevent relapse, as defined by the authors.48–50 The 3 trials used different FGAs (see Supplementary table 2), and, given the small number of trials, the effects of FGAs were analyzed as a group. The pooled OR showed no statistically significant advantage in favor of FGAs (OR = 2.82, 95% CI = 0.54–14.75; P = .22; figure 3) with some evidence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 50.0%, P = .14).

Fig. 3.

Differences in Risk of Relapse in FEP Patients in Studies Comparing Antipsychotic Medications With Placebo. FEP, first-episode psychosis; FGAs, first-generation antipsychotics; M-H random, Mantel-Haenszel method random effects; CI, confidence interval. Note: event = number of relapses; weight = it is indicated by the size of the square on each graph line and is related to the number of participants and events in the study.

Second-Generation Antipsychotics Vs First-Generation Antipsychotics.

Four trials including 1055 participants examined SGAs vs FGAs.3,51–53 One evaluated relapses as defined by the authors,3 and 3 defined relapse as admission to hospital.51–53 Two trials compared risperidone vs haloperidol,3,51 one clozapine vs chlorpromazine52 and one haloperidol vs a range of SGAs including amisulpride, olanzapine, quetiapine, or ziprasidone.53 To perform the analysis, 3 subgroups were established, risperidone vs haloperidol, clozapine vs chlorpromazine, and haloperidol vs a range of SGAs (which included the combined data from the amisulpride, olanzapine, quetiapine, and ziprasidone groups). Second, considering the small number of studies, the effects of SGAs vs FGAs were further pooled as a group (figure 4). There was no evidence of inconsistency across subgroups (I2 = 11.0%, P = .29) or overall estimates (I2 = 0.0%, P = .53). Figure 4 shows a trend toward statistical significant superiority for risperidone vs haloperidol (OR = 1.54, 95% CI = 0.98–2.42; P = .06), whereas no significant differences were found in relapse data for clozapine vs chlorpromazine (OR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.24–2.78; P = .74) or haloperidol vs a range of SGAs (OR = 1.38, 95% CI = 0.71–2.69; P = .34). The overall pooled OR yielded a statistically significant difference in favor of SGAs compared with FGAs (OR = 1.47, 95% CI = 1.07–2.01; P < .02). The NNT with SGAs to prevent one relapse was approximately 10.

Fig. 4.

Differences in Risk of Relapse in FEP Patients in Studies Comparing SGAs With FGAs. FEP, first-episode psychosis; FGAs, first-generation antipsychotics; SGAs, second-generation antipsychotics; M-H random, Mantel-Haenszel method random effects; CI, confidence interval. Note: event = number of relapses; weight = it is indicated by the size of the square on each graph line and is related to the number of participants and events in the study.

Four trials reported on discontinuation of medication due to adverse events. No significant superiority for any of the individual SGAs compared with the FGAs was found. When discontinuation rates were pooled across studies, there were no statistically significant advantages for the risperidone vs haloperidol subgroup (OR = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.72–2.09; P = .44) or the overall SGA vs FGA estimate (OR = 1.50, 95% CI = 0.99–2.27; P = .06).

First-Generation Antipsychotics Vs First-Generation Antipsychotics.

One small trial including 26 participants compared the effectiveness of 2 different FGAs (ie, pimozine vs flupenthixol) in preventing relapse defined as admission to hospital with no differences found between treatment groups (OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.19–5.29; P = 1.00).54

Medication Maintenance Vs Discontinuation.

One trial that involved 128 FEP patients evaluated maintenance vs guided discontinuation of pharmacological therapy (SGAs including risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, clozapine, and zuclopenthixol) in the prevention of relapse, as defined by the authors.55 This trial found that maintenance of treatment was statistically significantly superior compared with guided discontinuation for relapse prevention (OR = 2.91, 95% CI = 1.33–6.37; P < .01). Conversely, there was no statistically significant reduction in mean bed days for patients on medication maintenance compared with those on discontinuation (WMD = −23.31 d, 95% CI = −65.71 to −25.09 d; P = .38). The NNT for treatment maintenance was 5.

Sensitivity Analysis

Analyses were performed using both relative risks and OR as measures of effect size. All statistically significant differences in outcomes estimated via ORs remained significant when outcomes were pooled using relative risk measures. Similarly, nonsignificant differences in outcomes pooled via ORs remained statistically nonsignificant when outcomes were estimated using relative risk measures. Regarding publication bias, there was no clear evidence of funnel plot asymmetry (trial effect vs trial size) in any analysis (Supplementary figure 1).

Assessment of Risk of Bias

A description of the conduct of the trials included in the meta-analysis and assessment of the risk of bias are presented in Supplementary figure 2. In brief, 8 trials described adequate generation of random sequences,39–42,44–46,53 8 fully disclosed adequate allocation concealment procedures,39–43,45,53,55 6 provided explicit description of blinded assessment of relapse outcomes,39,40,43–45,48 10 were judged to adequately address incomplete data,39–41,43–48,52 7 prospectively measured relapse rates,3,40,45,47,48,51,55 and 11 trials assessed relapse according to prespecified criteria.3,39,40,43,45,48–51,54,55

Discussion

It has been argued that the early years beyond the first episode are crucial in setting the parameters for longer term recovery and outcome.56,57 Relapse early in the course of psychosis is likely to interfere with major developmental challenges such as identity formation, the founding of peer networks, vocational training, and intimate relationships. This is the first study, to the best of our knowledge, to systematically evaluate the effectiveness of all available interventions in the prevention of relapse in young people who have experienced an FEP.

Psychosocial Interventions

Specialist FEP Programs.

Three trials involving 679 patients demonstrated specialist FEP programs to be effective in preventing relapse in relation to TAU. These findings are in agreement with previous uncontrolled research that has indicated that comprehensive early intervention approaches showed promise in reducing symptoms, hospital admissions, and improving functional outcomes.11,58–61

This is the first study to provide meta-analytic evidence for the effectiveness of specialist FEP programs in reducing relapse rates as well as hospital days in the first 2 years after psychosis onset. Given that the available evidence indicates that some of the gains of specialist FEP programs are eroded over longer time periods,56,62 future trials should investigate the long-term effect of FEP programs in relapse prevention. Recent evidence suggests that the reduction of hospital days associated with specialist FEP programs may be maintained over 5 years of follow-up.63 Thus, the duration of FEP programs as well as the duration of the follow-up are equally important aspects to consider in future research.

CBT and Relapse Prevention.

The available evidence indicated CBT, in combination with early intervention programs, was not more effective for the prevention of relapse in FEP patients than early intervention programs alone. In addition, CBT showed no clinical benefits on relapse rates compared with either supportive counseling or TAU. While this finding is in keeping with a recent clinical trial that demonstrated that CBT for acute psychosis had no significant effects on rates of relapse at 12 or 24 months,29 several caveats need to be raised.

Firstly, specialist FEP programs provided a comprehensive range of interventions such as individualized crisis management plans and cognitive-behavioral strategies. As a result, these programs are likely to include a substantial proportion of therapeutic components usually offered in CBT interventions, thus making it difficult to find significant differences between treatment groups. Secondly, the study that showed no superiority of CBT compared with supportive counseling or TAU evaluated the effectiveness of an intensive CBT intervention provided within 5 weeks of admission in young acutely ill patients.43 It is likely that a CBT intervention needs to be offered over longer periods of time to obtain long-term preventative benefits. In addition, it may be plausible that young acutely ill patients do not benefit from CBT prevention strategies. This population clearly differs from clinically stable patients included in earlier psychosocial studies of relapse prevention for whom positive findings have been demonstrated.64 Thirdly, Edwards et al65 tested a CBT intervention aimed at reducing substance abuse in FEP psychosis. Cognitive-based interventions may need to be further refined to specifically target relapse prevention and address several risk factors simultaneously in FEP patients. When taken together, these findings suggest that targeted intensive CBT may need to be implemented when clinically remitted participants experience early warning signs (EWSs) of relapse as opposed to delivery of cognitive-behavioral strategies in the acute phase of the illness.64

Multimodal Relapse Prevention Therapy.

A recent clinical trial suggested the short-term effectiveness of a novel 7-month multimodal CBT intervention, delivered both to the individual and the family, for relapse prevention in remitted FEP patients compared with a specialist youth FEP program.45 The relapse prevention therapy comprised 5 phases of therapy underpinned by a relapse prevention framework and focused upon increasing awareness for the risk of setbacks and how to minimize them, identification of potential EWSs of relapse, and formulation of an individualized relapse prevention plan. Family intervention also incorporated psychoeducation regarding relapse risk as well as a review of EWSs and formulation of a relapse prevention plan. Taken together, these data lend support to the contention that multimodal CBT interventions specifically designed to prevent relapse offered to remitted FEP patients may improve further upon relapse rates achieved by specialist FEP services. However, the long-term effectiveness of this intervention remains to be established, and the findings of this trial need to be replicated in larger and more powerful studies.

Family Interventions.

Pooled treatment effects showed that family interventions were not significantly effective for relapse prevention in young FEP patients. However, participants, follow-ups, and interventions varied substantially across the only 2 trials examining family interventions. While one trial with positive findings included male participants and tested an intervention consisting of group and individual counseling sessions for 18 months,47 the other trial, which showed no difference between treatment conditions, evaluated a brief individual intervention comprising 7 sessions of psychoeducation.46 Similarly, the extant literature consistently shows that longer term family programs produce stronger clinical effects than shorter interventions in multiepisode patients.66 Taken together, these results indicate that longer family interventions may be needed in order to obtain clinical benefits in FEP patients.

Given the robust evidence for relapse prevention for family interventions in the later phases of schizophrenia66,67 and the theoretical potential of these interventions to prevent psychotic relapse,68 it is surprising that there is such a small number of RCTs evaluating their effectiveness in FEP patients. Further research is warranted to determine the effectiveness of family interventions in young people with an FEP.

Antipsychotic Medication and Relapse Prevention in FEP

The few trials comparing FGAs with placebo suggested that the former may be more effective in preventing relapse. However, these trials varied considerably in design and antipsychotic treatment, and the random-effects model showed no statistically significant advantage in favor of FGAs. Given that all individual estimates were in the same direction, the lack of statistically significant results is likely to be due to the heterogeneity of trials as well as the small size of individual studies. Random-effects model provide conservative overall estimates in the presence of heterogeneity between studies. Nonetheless, only FGAs were tested, and these trials had design aspects that could limit the generalizability of the findings to clinical practice. Specifically, 2 of the 3 relevant trials reported a small sample size and did not specify the criteria used to determine clinical remission.49,50 In addition, the trial by McCreadie et al50 included patients who took part in a previous study and had not experienced relapse.

It is important to highlight the limited placebo-controlled data on the effectiveness of antipsychotic medication in FEP patients. Furthermore, no clinical trial has been conducted to test the effectiveness of SGAs vs placebo in preventing relapse in FEP. Interestingly, data from this meta-analysis show that approximately 40% of FEP patients did not experience any relapse over 1-year follow-up although they were not receiving active treatment. Research also indicates that around 20% of patients will only experience one psychotic episode,69 and there are uncontrolled studies that suggest that minimal or no use of antipsychotics combined with intensive psychosocial treatments for FEP patients may be more effective than antipsychotic medication alone.18,61,69–71 However, these latter findings are based on secondary analysis of nonrandomized comparisons, and no placebo-controlled studies have examined the effectiveness of placebo in combination with specifically designed psychosocial interventions in preventing relapse. When taken together, findings from this and previous studies indicate that there is the need to evaluate, in a controlled fashion, the effectiveness of antipsychotic medication plus TAU vs a specialist FEP program with no use of antipsychotic medication in preventing relapse in young patients with an FEP.

Given the small number of relevant trials comparing SGAs with FGAs, results for the newer generation of antipsychotics were pooled in an exploratory manner. Four trials involving 1055 FEP patients showed the former to be, as a class, significantly more effective in preventing relapse. These results are consistent with previous findings in patients with long-term schizophrenia.17 While the overall pooled OR yielded a significant superiority of SGAs compared with FGAs, no statistically significant advantage was found for individual SGAs. However, given the design particularities of individual studies, including the different agents, doses, and relapse criteria employed, these meta-analytic results should be considered as a preliminary exploration of the potential of SGAs to prevent relapse in patients with an FEP. Further RCTs are warranted to establish the relative effectiveness of the newer agents in preventing relapse.

Finally, only one trial examined the effectiveness of a guided discontinuation strategy vs maintenance treatment in young patients with psychosis. The discontinuation strategy consisted of gradual symptom-guided tapering of dosage and discontinuation if feasible plus restoration of antipsychotic treatment if early EWSs of relapse emerged. Treatment maintenance was superior to the discontinuation strategy in preventing relapse during the first 18 months following clinical remission; however, there was no difference between treatment groups in number of hospital days or social functioning.55 Previous studies have also suggested that given the significant side effects associated with antipsychotics,72 the benefits of long-term use of medication in reducing relapse rates may exact a price in occupational terms.48 Given that around 20% of FEP patients do not relapse although they are not on active medication,48,69 it is essential to determine those who will experience only one episode in order to determine the most cost-effective treatment approach. Furthermore, the effectiveness of discontinuation strategies in FEP patients needs to be investigated in combination with intensive psychosocial treatments.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Firstly, trials included in the meta-analysis varied substantially in design, relapse and remission criteria employed, and the clinical characteristics of the participants (ie, some trials included clinically remitted participants, whereas others recruited acute patients whose treatment and follow-up were continued). Given the small number of studies for each comparison, formal analysis of these aspects was not possible. However, with the exception of family interventions and FGAs vs placebo, pooling treatment effects in the diverse comparisons showed that all estimates were in the same direction with no evidence of statistical heterogeneity. This suggests that the subgroups of RCTs (ie, specialist FEP programs vs both TAU and individual generic CBT and FGAs vs SGAs) were clinically meaningful, and comparisons were sufficiently homogeneous to obtain summary effect estimates across subgroups.20 Regardless, research on relapse prevention would clearly benefit from consensus regarding the relapse and clinical remission criteria employed.73 Most definitions of relapse included either significant worsening of psychotic symptoms or hospital readmission. Future relapse criteria should also include objective measurement of functional consequences of relapse. It is therefore essential to refine the criteria used to assess relapse and remission in order to make further progress in this area.

Secondly, the duration of follow-ups also varied across trials. While most trials included follow-ups of 12–18 months, studies varied in the timing of baseline assessment in relation to the initiation of pharmacological treatment, which may have influenced the rates of relapse obtained. Moreover, given that previous research has found relapse rates increase over longer periods of time,4 findings from the present meta-analysis can only be generalized to the first 2 years after treatment initiation. Longer clinical trials are clearly needed to determine the long-term effectiveness of these interventions. Thirdly, trial conduct, particularly for pharmacological trials, was poor (ie, allocation concealment, prespecified outcome criteria), making assessment of the potential for biased estimates of treatment effect difficult.22 Given the relationship between poor reporting and larger treatment effects,74 findings reported by some trials may have overestimated summary treatment effects. However, it was not possible to perform a sensitivity analysis of methodological quality because of the small number of trials for each treatment category. In addition, some studies determined relapse rates by follow-up of those who responded to acute treatment that may distort the effectiveness of initial randomization. Finally, given that some potentially eligible pharmacological trials did not report on relapse/readmission rates,37,38 the possibility of reporting bias cannot be discarded.

We had hoped to examine the effects of interventions on number of admissions compared with relapse rates using prespecified criteria, duration of relapse, or bed days, but unfortunately data on these aspects were extremely scarce. Further research should examine these issues in order to determine whether interventions are also effective in reducing the duration of subsequent episodes and/or number of bed days.

Finally, as with all systematic reviews, publication bias is a potential source of error. While the funnel plot of all trials showed no evidence of publication bias, it was not possible to formally assess such bias because of the small number of trials for each comparison. That said, considerable efforts were made to identify unpublished trials, and nearly half of the trials we included found no significant treatment effect.

Future Research

The available evidence suggests that intensive psychosocial interventions together with low-dose medication strategies—in accordance with early psychosis treatment guidelines—are effective in reducing relapse rates in young patients with FEP psychosis. However, given the clinical and social relevance of preventing relapse early in the course of psychosis, it is somewhat surprising—the modest controlled evidence on relapse prevention strategies for FEP patients. Well-conducted trials of all interventions are needed. Such trials should include consensual and prospective relapse and remission criteria and should be properly randomized and powered. Further research needs to address several salient issues such as the relative effectiveness of individual antipsychotics, psychosocial and family interventions, their long-term effects on relapse rates as well as impact on bed days, hospital admissions, quality of life, functioning, and duration of subsequent episodes. Future studies should also investigate the effectiveness and safety of placebo and medication discontinuation strategies in combination with intensive psychosocial treatments in the early phase of psychosis. Finally, further research should make efforts to identify those FEP patients who will only experience one psychotic episode and therefore may not need antipsychotic medication to prevent psychotic relapses.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures 1 and 2 and tables 1 and 2 are available at http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org.

Funding

Marqués de Valdecilla Public Foundation—Research Institute (FMV-IFIMAV), Santander, Spain; Colonial Foundation and a Program Grant from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (350241).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors report no additional financial or other affiliation relevant to the subject of this article. The authors acknowledge Sara Gook of ORYGEN Research Centre-University of Melbourne and Dr César González-Blanch of University Hospital “Marqués de Valdecilla” for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this article. The authors also thank authors who provided additional information including Dr Susy Harrigan, Dr Jane Edwards, Dr. Lex Wunderink, Dr Lone Petersen, Dr Gerard Leavey, Dr Nina Schooler, Dr Wolfgang Gaebel, Dr Hans-Jürgen Möller, Dr Jeffrey A. Lieberman, Dr Joseph P. McEvoy, and Dr John R. Bola.

References

- 1.Sanger TM, Lieberman JA, Tohen M, Grundy S, Beasley C, Tollefson GD. Olanzapine versus haloperidol treatment in first-episode psychosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:79–87. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman JA, Tollefson G, Tohen M, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus haloperidol. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1396–1404. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schooler N, Rabinowitz J, Davidson M, et al. Risperidone and haloperidol in first-episode psychosis: a long-term randomized trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:947–953. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al. Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:241–247. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Delman HM, Kane JM. Pharmacological treatments for first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31:705–722. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rummel C, Hamann J, Kissling W, Leucht S. New generation antipsychotics for first episode schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004410. CD004410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gitlin M, Nuechterlein K, Subotnik KL, et al. Clinical outcome following neuroleptic discontinuation in patients with remitted recent-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1835–1842. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiersma D, Nienhuis FJ, Slooff CJ, Giel R. Natural course of schizophrenic disorders: a 15-year followup of a Dutch incidence cohort. Schizophr Bull. 1998;24:75–85. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stephenson J. Delay in treating schizophrenia may narrow therapeutic window of opportunity. JAMA. 2000;283:2091–2092. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.16.2091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho BC, Andreasen NC, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, Magnotta V, Flaum M. Progressive structural brain abnormalities and their relationship to clinical outcome: a longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study early in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:585–594. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penn DL, Waldheter EJ, Perkins DO, Mueser KT, Lieberman JA. Psychosocial treatment for first-episode psychosis: a research update. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2220–2232. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Almond S, Knapp M, Francois C, Toumi M, Brugha T. Relapse in schizophrenia: costs, clinical outcomes and quality of life. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:346–351. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.4.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiden PJ, Olfson M. Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1995;21:419–429. doi: 10.1093/schbul/21.3.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:1–30. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care. London, UK: NICE; 2002; [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leucht S, Barnes TR, Kissling W, Engel RR, Correll C, Kane JM. Relapse prevention in schizophrenia with new-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1209–1222. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bola JR, Mosher LR. Treatment of acute psychosis without neuroleptics: two-year outcomes from the Soteria project. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191:219–229. doi: 10.1097/01.NMD.0000061148.84257.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenior ME, Dingemans PM, Linszen DH, de Haan L, Schene AH. Social functioning and the course of early-onset schizophrenia: five-year follow-up of a psychosocial intervention. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:53–58. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.0 [updated February 2008]: The Cochrane Collaboration. 2008. www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed February 15, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Review Manager (RevMan) [computer program] Version 5.0. Copenhagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008; [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egger M, Smith GD, Phillips AN. Meta-analysis: principles and procedures. Br Med J. 1997;315:1533–1537. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7121.1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Light RJ, Pillemer DB. Organizing a Reviewing Strategy. Summing Up: The Science of Reviewing Research. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1984. pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson H, McGorry P, Edwards J, et al. A controlled trial of cognitively oriented psychotherapy for early psychosis (COPE) with four-year follow-up readmission data. Psychol Med. 2005;35:1295–1306. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705004927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emsley R, Medori R, Koen L, Oosthuizen PP, Niehaus DJH, Rabinowitz J. Long-acting injectable risperidone in the treatment of subjects with recent-onset psychosis: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:210–213. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318167269d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garety PA, Fowler DG, Freeman D, Bebbington P, Dunn G, Kuipers E. Cognitive-behavioural therapy and family intervention for relapse prevention and symptom reduction in psychosis: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:412–423. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.043570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haddock G, Tarrier N, Morrison AP, Hopkins R, Drake R, Lewis S. A pilot study evaluating the effectiveness of individual inpatient cognitive-behavioural therapy in early psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34:254–258. doi: 10.1007/s001270050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuipers E, Holloway F, Rabe Hesketh S, Tennakoon L. An RCT of early intervention in psychosis: Croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team (COAST) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:358–363. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0754-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Linszen D, Dingemans P, Van der Does JW, et al. Treatment, expressed emotion and relapse in recent onset schizophrenic disorders. Psychol Med. 1996;26:333–342. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700034723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson DG, Woerner MG, Napolitano B, et al. Randomized comparison of olanzapine versus risperidone for the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia: 4-month outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:2096–2102. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gitlin M, Nuechterlein K, Subotnik KL, et al. Clinical outcome following neuroleptic discontinuation in patients with remitted recent-onset schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1835–1842. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berger GE, Proffitt TM, McConchie M, et al. Dosing quetiapine in drug-naive first-episode psychosis: a controlled, double-blind, randomized, single-center study investigating efficacy, tolerability, and safety of 200 mg/day vs. 400 mg/day of quetiapine fumarate in 141 patients aged 15 to 25 years. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1702–1714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sikich L, Frazier JA, McClellan J, et al. Double-blind comparison of first- and second-generation antipsychotics in early-onset schizophrenia and schizo-affective disorder: findings from the treatment of early-onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders (TEOSS) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1420–1431. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keefe RS, Seidman LJ, Christensen BK, et al. Comparative effect of atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs on neurocognition in first-episode psychosis: a randomized, double-blind trial of olanzapine versus low doses of haloperidol. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:985–995. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Perkins DO, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in the treatment of early psychosis: a randomized, double-blind 52-week comparison. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1050–1060. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Craig TK, Garety P, Power P, et al. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. Br Med J. 2004;329:1067. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38246.594873.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grawe RW, Falloon IR, Widen JH, Skogvoll E. Two years of continued early treatment for recent-onset schizophrenia: a randomised controlled study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:328–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, et al. A randomised multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. BMJ. 2005;331:602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38565.415000.E01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Killackey E, et al. Acute-phase and 1-year follow-up results of a randomized controlled trial of CBT versus befriending for first-episode psychosis: the ACE project. Psychol Med. 2008;38:725–735. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tarrier N, Lewis S, Haddock G, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy in first-episode and early schizophrenia. 18-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:231–239. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edwards J, Elkins K, Hinton M, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a cannabis-focused intervention for young people with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2006;114:109–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gleeson JF, Cotton SM, Alvarez-Jimenez M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of relapse prevention therapy for first-episode psychosis patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:477–486. doi: 10.4088/jcp.08m04407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leavey G, Gulamhussein S, Papadopoulos C, Johnson Sabine E, Blizard B, King M. A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for families of patients with a first episode of psychosis. Psychol Med. 2004;34:423–431. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang M, Wang M, Li J, Phillips MR. Randomised-control trial of family intervention for 78 first-episode male schizophrenic patients. An 18-month study in Suzhou, Jiangsu. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1994;24:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crow TJ, MacMillan JF, Johnson AL, Johnstone EC. A randomised controlled trial of prophylactic neuroleptic treatment. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;148:120–127. doi: 10.1192/bjp.148.2.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kane JM, Rifkin A, Quitkin F, Nayak D, Ramos Lorenzi J. Fluphenazine vs placebo in patients with remitted, acute first-episode schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1982;39:70–73. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290010048009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McCreadie RG, Wiles D, Grant S, et al. The Scottish first episode schizophrenia study. VII. Two-year follow-up. Scottish Schizophrenia Research Group. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;80:597–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb03032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gaebel W, Riesbeck M, Wolwer W, et al. Maintenance treatment with risperidone or low-dose haloperidol in first-episode schizophrenia: 1-year results of a randomized controlled trial within the German Research Network on Schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1763–1774. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lieberman JA, Phillips M, Gu H, et al. Atypical and conventional antipsychotic drugs in treatment-naive first-episode schizophrenia: a 52-week randomized trial of clozapine vs chlorpromazine. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:995–1003. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial [see comment] Lancet. 2008;371:1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.The Scottish First Episode Schizophrenia Study V. One-year follow-up. The Scottish Schizophrenia Research Group. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:470–476. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wunderink L, Nienhuis FJ, Sytema S, Slooff CJ, Knegtering R, Wiersma D. Guided discontinuation versus maintenance treatment in remitted first-episode psychosis: relapse rates and functional outcome. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:654–661. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McGorry PD, Killackey E, Yung A. Early intervention in psychosis: concepts, evidence and future directions. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:148–156. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birchwood M, Todd P, Jackson C. Early intervention in psychosis. The critical period hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;172:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McGorry PD, Edwards J, Mihalopoulos C, Harrigan SM, Jackson HJ. EPPIC: an evolving system of early detection and optimal management. Schizophr Bull. 1996;22:305–326. doi: 10.1093/schbul/22.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carbone S, Harrigan S, McGorry PD, Curry C, Elkins K. Duration of untreated psychosis and 12-month outcome in first-episode psychosis: the impact of treatment approach. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100:96–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO, et al. Shortened duration of untreated first episode of psychosis: changes in patient characteristics at treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1917–1919. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cullberg J, Levander S, Holmqvist R, Mattsson M, Wieselgren IM. One-year outcome in first episode psychosis patients in the Swedish Parachute project. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:276–285. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.02376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harris MG, Henry LP, Harrigan SM, et al. The relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome: an eight-year prospective study. Schizophr Res. 2005;79:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, et al. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness: the OPUS trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:762–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gumley A, O'Grady M, McNay L, Reilly J, Power K, Norrie J. Early intervention for relapse in schizophrenia: results of a 12-month randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioural therapy. Psychol Med. 2003;33:419–431. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703007323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Edwards J, Harris MG, Bapat S. Developing services for first-episode psychosis and the critical period. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2005;48:s91–s97. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pitschel-Walz G, Leucht S, Bauml J, Kissling W, Engel RR. The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalization in schizophrenia–a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:73–92. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pilling S, Bebbington P, Kuipers E, et al. Psychological treatments in schizophrenia: I. Meta-analysis of family intervention and cognitive behaviour therapy. Psychol Med. 2002;32:763–782. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Gleeson JF, Cotton SM, et al. Differential predictors of critical comments and emotional over-involvement in first-episode psychosis [published online ahead of print December 15, 2008] Psychol Med. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004765. doi:10.1017/S0033291708004765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bola JR, Mosher LR. At issue: predicting drug-free treatment response in acute psychosis from the Soteria project. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:559–575. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lehtinen V, Aaltonen J, Koffert T, Rakkolainen V, Syvalahti E. Two-year outcome in first-episode psychosis treated according to an integrated model. Is immediate neuroleptisation always needed? Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15:312–320. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(00)00400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ciompi L, Dauwalder HP, Maier C, et al. The pilot project ‘Soteria Berne'. Clinical experiences and results. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1992;161(suppl 18):145–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wirshing DA. Schizophrenia and obesity: impact of antipsychotic medications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 18):13–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lasser RA, Nasrallah H, Helldin L, et al. Remission in schizophrenia: applying recent consensus criteria to refine the concept. Schizophr Res. 2007;96:223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Juni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42–46. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.