Abstract

Loss of IκB kinase (IKK) β-dependent NF-κB signaling in hematopoietic cells is associated with increased granulopoiesis. Here we identify a regulatory cytokine loop that causes neutrophilia in Ikkβ−deficient mice. TNF-α–dependent apoptosis of myeloid progenitor cells leads to the release of IL-1β, which promotes Th17 polarization of peripheral CD4+ T cells. Although the elevation of IL-17 and the consecutive induction of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor compensate for the loss of myeloid progenitor cells, the facilitated induction of Th17 cells renders Ikkβ-deficient animals more susceptible to the development of experimental autoimmune encephalitis. These results unravel so far unanticipated direct and indirect functions for IKKβ in myeloid progenitor survival and maintenance of innate and Th17 immunity and raise concerns about long-term IKKβ inhibition in IL-17–mediated diseases.

Keywords: CD34, IL-7R, IKKβ inhibitor

NF-κB is a potent transcription factor that orchestrates many biological functions essential for a wide range of inflammatory, apoptotic, and immune processes (1). NF-κB consists of homo- or heterodimers of a family of five structurally related proteins—RelA/p65, RelB, c-Rel, p50/p105, and p52/p100—which are kept in an inactive state by binding to members of the IκB family that include IκBα, IκBβ, and IκBε, as well as p105 and p100, which are the precursors of p50 and p52, respectively. Activating signals, including proinflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α and IL-1β) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns coalesce at the IKK complex composed of the two catalytical subunits IκB kinase (IKK) α and IKKβ in addition to the regulatory subunit IKKγ. Upon activation, the IKK complex phosphorylates NF-κB–bound IκB, which is subsequently polyubiquitinated and degraded by the proteasome, thereby liberating NF-κB dimers that can now translocate to the nucleus to initiate transcription (2).

Apart from its importance in the pathogenesis of various chronic inflammatory diseases, classical IKKβ-dependent NF-κB activation represents a key link connecting inflammation and cancer (3, 4). Therefore, pharmacological inhibition of this signaling cascade by using specific IKKβ inhibitors has been suggested as a promising strategy for the treatment of inflammatory and malignant diseases (5). However, potential caveats associated with long-term inhibition of IKKβ are the impairment of adaptive immunity as well as increased IL-1β processing and secretion by differentiated macrophages and neutrophils. Both genetic and pharmacological studies have demonstrated the requirement of functional IKKβ/NF-κB signaling for the development and maintenance of T and B lymphocytes (6–8). In addition, in myeloid cells, NF-κB is involved in the negative regulation of IL-1β release. NF-κB–controlled gene products inhibit caspase 1 and proteinase 3 (PR3) in LPS-stimulated macrophages and neutrophils, respectively, thereby suppressing pro–IL-1β processing. In case of IKKβ inhibition, this negative regulation is missing, thus leading to a counterintuitive increase of IL-1β release, although NF-κB–mediated IL-1β mRNA induction is efficiently inhibited, which ultimately renders mice with myeloid-specific ablation of Ikkβ highly susceptible to endotoxin-induced shock. Importantly, similar effects can be observed upon prolonged high-dose administration of an IKKβ inhibitor (9).

In sharp contrast to the loss of IKKβ-deficient B and T cells, both pharmacological blockade and genetic deletion of Ikkβ induce a marked increase of CD11b+/Gr-1+ neutrophils (6, 8, 9). However, the exact mechanism causing this neutrophilia is unknown; but, because it potentiates endotoxin toxicity and IL-1β release (9), it represents a major additional concern for a potential long-term use of IKKβ inhibitors. A detailed understanding of the underlying pathophysiology could therefore help in the development of strategies that prevent the serious side effects caused by the loss of myeloid IKKβ function.

Results

Neutrophilia in IkkβΔ Mice Is Dependent on TNF-α and Occurs in the Absence of Mature T and B Cells.

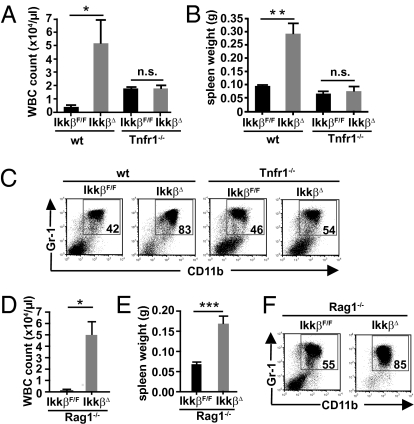

Genetic deletion of Tnfr1 prevents lymphocyte apoptosis in mice treated with the specific IKKβ inhibitor ML120B as well as in animals transplanted with fetal liver cells from complete Ikkβ−/− KO mice (6, 8). Furthermore, granulocytosis does not develop in Ikkβ−/− radiation chimera when TNF-α signaling is blocked. Thus, we hypothesized that the TNF-dependent apoptosis of Ikkβ-deficient lymphocytes might be causally involved in the development of granulocytosis. To test whether it is the loss of Tnfr1 or specifically the absence of lymphocytes in inducible IkkβΔ mice that could prevent neutrophilia, we crossed IkkβΔ to Tnfr1−/− and Rag1−/− mice, respectively. Similarly to radiation chimera adoptively transferred with fetal liver cells from Ikkβ−/− whole-body KOs, absence of TNF-R1 prevented loss of bone marrow lymphocytes in IkkβΔ mice. Although Tnfr−/− mice displayed slightly elevated leukocyte counts themselves, block of TNF signaling prevented massive granulocytosis in IkkβΔ mice 21 d after induction of Ikkβ deletion by poly(I:C) (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, development of splenomegaly [a surrogate marker of peripheral neutrophilia (9)] was inhibited and the number of bone marrow CD11b+/Gr-1+ neutrophils in Tnfr1−/−/IkkβΔ compound mutants was comparable to their respective controls (Fig. 1 B and C). In contrast, absence of mature B and T cells in Rag1−/−/IkkβΔ double mutants did not affect leukocytosis or splenomegaly (Fig. 1 D and E). Moreover, approximately 85% of bone marrow cells in Rag1-deficient IkkβΔ mice comprised CD11b+/Gr-1+ neutrophils (Fig. 1F), thereby partially disproving our initial hypothesis. Although granulocytosis in IkkβΔ mice was dependent on TNF-R1 signaling, loss of mature lymphocytes had no effect.

Fig. 1.

Granulocytosis in IkkβΔ mice requires TNFR-1 and occurs in the absence of lymphocytes. WBC counts (A) and spleen weights (B) of IkkβF/F, IkkβΔ, Tnfr1−/−, and IkkβΔ/Tnfr1−/− double KO mice 21 d after poly(I:C) administration. Data are mean ± SE from at least three mice (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; n.s, not significant). (C) Representative FACS plots of CD11b+/Gr-1+ cells in bone marrow of IkkβF/F, IkkβΔ, Tnfr1−/−, and IkkβΔ/Tnfr1−/− double KO mice. Numbers within the plot indicate the percentage of double-positive cells. Plots are representative of at least four mice per genotype. (D and E) WBC counts (D) and spleen weights (E) of Rag1−/− and IkkβΔ/Rag1−/− compound mutants 21 d after poly(I:C) administration. Data are mean ± SE from at least three mice (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0001). (F) Representative FACS plots of CD11b+/Gr-1+ cells in bone marrow of Rag1−/− and IkkβΔ/Rag1−/− double KO mice. Plots are representative of five mice per genotype.

Blockade of IL-1β Prevents Neutrophilia in IkkβΔ Mice.

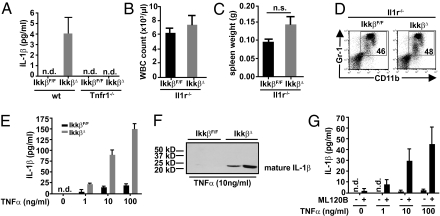

Previously, we had shown that Ikkβ-deficient myeloid cells secrete increased levels of IL-1β in response to LPS (9). IL-1 is a potent promoter of granulopoiesis (10), and we therefore asked whether IL-1β might be involved in the marked granulocytosis in IkkβΔ mice and whether this was connected to TNF-α–mediated effects in IKKβ-deficient myeloid cells. Indeed, plasma IL-1β levels in IkkβΔ mice 21 d after injection of poly(I:C) were elevated in a TNF-α–dependent manner (Fig. 2A). Moreover, when we deleted Il1r in IkkβΔ mice, leukocyte counts were normalized and splenomegaly could no longer be observed in Il1r−/−/IkkβΔ double mutants (Fig. 2 B and C), and the number of bone marrow CD11b+/Gr-1+ neutrophils was also comparable to that in Il1r−/− controls (Fig. 2D), suggesting that TNF-α–dependent release of IL-1β causes granulocytosis in IkkβΔ mice.

Fig. 2.

IL-1β is elevated in a TNF-α–dependent manner and is associated with neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice. (A) Plasma IL-1β levels in IkkβF/F, IkkβΔ, Tnfr1−/−, and IkkβΔ/Tnfr1−/− double KO mice. Data are mean ± SE from at least eight mice (n.d., not detected). (B and C) WBC counts (B) and spleen weights (C) of Il1r−/− and IkkβΔ/Il1r−/− double KO mice 21 d after poly(I:C) administration. Data are mean ± SE from at least three mice. (D) Representative FACS plots of CD11b+/Gr-1+ cells in bone marrow of Il1r−/− and IkkβΔ/Il1r−/− double KO mice. Plots are representative of at least four mice per genotype. (E and F) IL-1β levels in the supernatants of bone marrow cells from IkkβF/F and IkkβΔ mice treated with increasing amounts of TNF-α for 24 h determined by ELISA (E) or immunoblot analysis (F). Data are mean ± SE from at least three mice. (G) IL-1β levels in the supernatants of bone marrow cells from WT mice treated with or without ML120B (30 μM) and increasing amounts of TNF-α for 24 h. Data are mean ± SE from at least three mice.

To identify the cellular source of IL-1β, we cultured bone marrow cells from IkkβΔ and IkkβF/F control mice in the presence or absence of TNF-α. Within 24 h, Ikkβ-deficient cells, when stimulated with TNF-α, secreted large amounts of processed IL-1β into the supernatant that markedly exceeded the amount of IL-1β released by control cells (Fig. 2 E and F). To rule out that this was simply caused by differences in the cell type composition in IkkβΔ bone marrow, such as loss of B220+ cells and the substantial increase of CD11b+/Gr-1+ cells, we treated WT bone marrow cells in the absence or presence of the specific IKKβ inhibitor ML120B along with increasing amounts of TNF-α. Similarly to IkkβΔ bone marrow cells, TNF-α stimulation strongly enhanced IL-1β release in a dose-dependent manner when IKKβ was blocked pharmacologically, whereas treatment with TNF-α alone induced only marginal amounts of IL-1β (Fig. 2G).

IKKβ Inhibition Sensitizes Myeloid Progenitors to TNF-α–Induced Apoptosis.

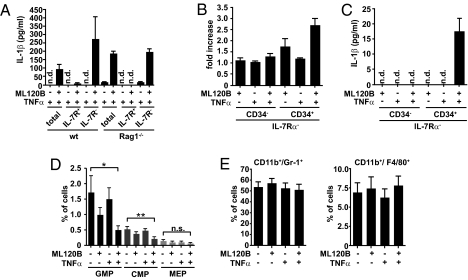

Based on our findings that Rag1-deficient IkkβΔ mice continued to have elevated neutrophil numbers, we hypothesized that cells other than lymphocytes would represent the main source of IL-1β. To confirm this, we separated WT bone marrow cells on the basis of IL-7 receptor (IL-7R)–α expression and measured IL-1β release after TNF-α stimulation in the presence of ML120B. Indeed, IKKβ inhibition did not affect IL-1β secretion by IL-7Rα+ cells (representing the majority of lymphocytes); however, within 24 h, IL-1β levels were greatly increased in supernatants from purified IL-7Rα− WT cells as well as from Rag1-deficient animals (Fig. 3A), providing evidence that myeloid cells themselves represented the actual source of IL-1β that was responsible for granulocytosis in IkkβΔ mice.

Fig. 3.

TNF-α induces apoptosis of myeloid progenitors and IL-1β release upon IKKβ inhibition. (A) IL-1β levels in the supernatants of total, IL-7Rα+, and IL-7Rα− bone marrow cells from WT and Rag1−/− mice stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for 24 h in the presence or absence of ML120B (30 μM). Data are mean ± SE from at least three mice. (B) Induction of apoptosis determined by annexin V staining of IL-7Rα−/CD34+ and IL-7Rα−/CD34− cells from WT mice stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for 4 h in the presence or absence of ML120B (30 μM). Data are mean ± SE from at least four mice. (C) IL-1β levels in the supernatants of IL-7Rα−/CD34+ progenitor and IL-7Rα−/CD34− cells from WT mice stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for 24 h in the presence or absence of ML120B (30 μM). Data are mean ± SE from at least four mice. (D) Loss of GMPs and CMPs upon combined treatment with TNF-α and ML120B: IL-7Rα− WT bone marrow cells were stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) in the presence or absence of ML120B (30 μM) for 4 h. Lin−/IL-7Rα−/Sca-1−/c-Kit+ fraction was subdivided into FcγRII/IIIhiCD34+ (GMPs), FcγRII/IIIlowCD34+ (CMPs), and FcγRII/IIIlowCD34− (megakaryocyte/erythrocyte lineage restricted progenitors; MEP). Data are mean ± SE from at least five mice. (E) Number of CD11b+/Gr-1+ and CD11b+/F4/80+ cells remain unchanged in WT bone marrow cells stimulated with TNF-α (10 ng/mL) for 4 h in the presence or absence of ML120B (30 μM). Data are mean ± SE from at least four mice.

In Ikkβ-deficient macrophages, increased secretion of processed IL-1β is associated with LPS induced apoptosis (9). Surprisingly, within 4 h, combined TNF-α/ML120B treatment induced apoptosis of IL-7Rα−/CD34+ progenitor cells but not differentiated IL-7Rα−/CD34− cells coinciding with IL-1β release (Fig. 3B and Figs. S1A and S2A). This suggested that IKKβ inhibition rendered myeloid progenitors more susceptible to TNF-α–induced apoptosis than mature IL-7Rα− cells, and indeed, when we compared IL-1β release by purified IL-7Ra−/CD34− and IL-7Ra−/CD34+ cells, only the latter secreted IL-1β (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, FACS analysis demonstrated substantial loss of Lin−/IL-7Rα−/c-kit+/Sca-1−/CD34+/FcγRII/IIIlo and Lin−/IL-7Rα−/c-kit+/Sca-1−/CD34+/FcγRII/IIIhi cells, which represent common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) and granulocyte/macrophage lineage-restricted progenitors (GMPs), respectively (11), in response to combined TNF-α/ML120B treatment ex vivo, whereas the number of both mature CD11b+/Gr-1+ and CD11b+/F4/80+ cells did not decrease (Fig. 3 D and E and Fig. S2B). This was in contrast to ex vivo differentiated Ikkβ-deficient bone marrow-derived macrophages that undergo apoptosis and release IL-1β when stimulated with LPS or TNF-α (Fig. S1B) (9). To functionally confirm that IKKβ-deleted CMPs and GMPs but not differentiated cells cause IL-1β release and neutrophilia in vivo, we examined IkkβΔmye mice, which selectively delete Ikkβ in fully differentiated macrophages and neutrophils but not in progenitor cells (Fig. S3A) (12). As expected, IkkβΔmye mice had normal leukocyte counts, their spleens were not enlarged, and the relative number of CD11b+/Gr-1+ neutrophils in IkkβΔmye bone marrow was comparable to those in their littermate controls (Fig. S3 B–D). Furthermore, when IkkβΔmye bone marrow cells were stimulated with TNF-α ex vivo, measurable amounts of IL-1β were secreted only in the presence of additional ML120B, which, however, did not exceed the amount released by control cells (Fig. S3E).

Enhanced IL-1β processing in LPS-stimulated Ikkβ-deficient myeloid cells is associated with increased caspase 1 and elevated PR3 activity in macrophages and neutrophils, respectively (9). To examine whether IL-1β secretion by Ikkβ-deficient myeloid progenitors cells in response to TNF-α was also dependent on the activity of caspase 1 or PR3, we stimulated whole bone marrow cells of Casp1−/− and Prtn3/Ela2−/− (deficient for both PR3 and neutrophil elastase) mice with TNF-α and ML120B. Whereas loss of caspase 1 indeed substantially reduced IL-1β release, Prtn3 deficiency did not (Fig. S4A). Interestingly, however, loss of Nlrp3 or Asc, two essential components of the NLRP3 inflammasome, one of the best characterized multiprotein complexes regulating caspase 1 activity (13), did not prevent neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice (Fig. S4B), demonstrating that caspase 1 is controlled in a NLRP3-independent manner in Ikkβ-deficient myeloid progenitor cells.

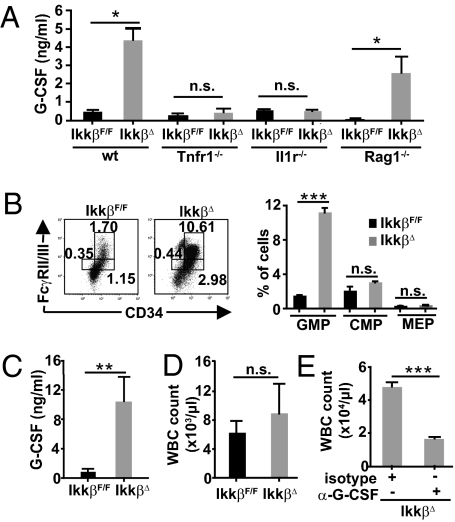

Plasma G-CSF Is Elevated in IkkβΔ Mice in a TNF-α/IL-1β–Dependent Manner.

After having identified the cellular source of IL-1β in IkkβΔ mice, we wanted to test whether important IL-1β downstream effectors that are known to directly stimulate myelopoiesis, such as G-CSF and GM-CSF (10, 14), were up-regulated in these mice as well. Although plasma GM-CSF was not detectable in any genotype, circulating G-CSF levels were nearly 10-fold increased in IkkβΔ mice compared with their littermate controls 21 d after the initial poly(I:C) injection, and deletion of Tnfr1 or Il-1r expectedly suppressed G-CSF elevation (Fig. 4A). In contrast, but in accordance with the sustained neutrophilia in Rag1−/−/IkkβΔ double mutants, absence of Rag1 did not decrease plasma G-CSF substantially (Fig. 4A). Moreover, G-CSF levels were normal in IkkβΔmye mice. G-CSF is mainly secreted by bone marrow stromal cells and monocytes (15). To rule out that Ikkβ-deficient bone marrow cells or bone marrow-derived macrophages secreted increased amounts of G-CSF and/or GM-CSF in a cell-autonomous manner, we isolated bone marrow cells and cultured them for 24 h ex vivo. However, neither G-CSF nor GM-CSF levels were increased in supernatants of TNF-α–stimulated IkkβΔ or TNF-α/ML120B–treated WT bone marrow cells. Moreover, after stimulation with IL-1β, TNF-α or LPS induction of mRNA levels encoding G-CSF or GM-CSF were not increased in ML120B-treated macrophages (Fig. S5), thus excluding the possibility that these granulopoiesis-stimulating cytokines were directly repressed in an IKKβ-dependent manner.

Fig. 4.

G-CSF is markedly increased and is responsible for GMP expansion and consecutive neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice. (A) G-CSF levels in the plasma from IkkβF/F, IkkβΔ, Tnfr1−/−, and IkkβΔ/Tnfr1−/−, Il1r−/−, and IkkβΔ/Il1r−/− double KO mice as well as Rag1−/− and IkkβΔ/Rag1−/− compound mutants 21 d after poly(I:C) administration. Data are mean ± SE from at least six mice (*P < 0.05). (B) Representative FACS plots and mean numbers of myeloid progenitors in IkkβF/F and IkkβΔ mice 21 d after poly(I:C) administration demonstrate a significant increase of GMP in IkkβΔ mice determined by FcγRII/III and CD34 expression in Lin−/IL-7Rα−/Sca-1−/c-Kit+ cells. Data are mean ± SE from three mice (***P < 0.0001). (C and D) Plasma G-CSF levels (C) and WBC counts (D) of IkkβF/F and IkkβΔ mice 5 d after poly(I:C) administration. Data are mean ± SE from at least five mice (**P < 0.01). (E) WBC count of IkkβΔ mice 21 d after poly(I:C) administration that had been injected daily with rat α-G-CSF or a respective isotype control. Data are mean ± SE from four mice (***P < 0.0001).

Because G-CSF is known to expand the myeloid progenitor population (16), we wanted to examine whether the increased G-CSF levels in IkkβΔ mice could counteract the acute loss of CMPs and GMPs induced by the combination of TNF-α and ML120B (Fig. 3D). Although the number of CMPs was only slightly increased, loss of IKKβ induced a marked (approximately sixfold) expansion of the GMP population (Fig. 4B), suggesting that it is the G-CSF–driven proliferation of granulocyte/macrophage lineage-restricted progenitors that causes neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice. In agreement with this notion, elevated G-CSF plasma levels preceded granulocytosis. When we examined mice only 5 d after poly(I:C) administration, G-CSF levels had already massively increased IkkβΔ whereas leukocyte counts remained normal (Fig. 4 C and D). Conversely, neutralization of G-CSF abolished development of neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice (Fig. 4E).

Elevated IL-1β Causes a Strong Th17 Polarization in IkkβΔ Mice.

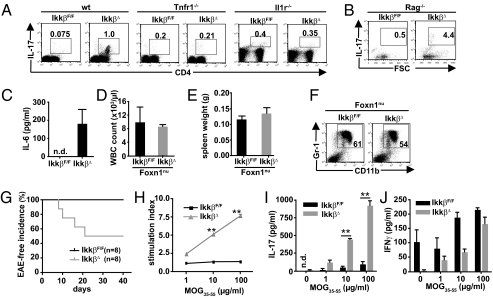

IL-1β has been shown to be essential for IL-17 production by subsets of αβ and γδ T cells (17, 18), and IL-17 is an important promoter of G-CSF production (19). Therefore, we reasoned that elevated IL-1β levels in IkkβΔ mice would trigger a pronounced Th17 polarization, which was responsible for G-CSF elevation. As expected, IkkβΔ mice demonstrated a dramatic increase (approximately 20-fold) in CD4+ Th17 cells (Fig. 5A). In line with a missing IL-1β release as well as a blockade in IL-1 signaling in Tnfr1-deficient and Il-1r–deleted IkkβΔ KOs, respectively, this increase was no longer observable in either of the two compound mutants (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, IkkβΔmye mice, which lacked elevated plasma IL-1β, also did not reveal an enhanced Th17 differentiation of peripheral T cells. Interestingly, IL-17 expression was greatly induced in Rag1−/−/IkkβΔ mice despite the absence of mature T cells, in agreement with the sustained neutrophilia in these mice (Fig. 5B). However, it was recently shown that Rag1−/− mice can maintain normal neutrophil counts as a result of IL-17 production in double-negative thymic cells that express intracellular CD3 and that colonize mesenteric lymph nodes (20), and indeed these cells were sufficient to mount marked IL-17 production in Rag1−/−/IkkβΔ double mutants (Fig. S6).

Fig. 5.

IkkβΔ mice develop a strong Th17 polarization and show increased susceptibility to develop EAE (A and B) Representative FACS plots of IL-17–secreting CD4+ cells in mesenteric lymph nodes of IkkβF/F, IkkβΔ, Tnfr1−/−, and IkkβΔ/Tnfr1−/−, Il1r−/−, and IkkβΔ/Il1r−/− double KO mice (A), as well as IL-17–secreting cells in Rag1−/− and IkkβΔ/Rag1−/− compound mutants (B). Plots are representative of at least four animals per genotype. (C) Plasma IL-6 levels in IkkβF/F and IkkβΔ mice. Data are mean ± SE from at least six mice (n.d., not detected). (D and E) WBC counts (D) and spleen weights (E) of NU-Foxn1nu and NU-Foxn1nu/IkkβΔ double KO mice. Data are mean ± SE from at least three mice. (F) Representative FACS plots of CD11b+/Gr-1+ cells in bone marrow of NU-Foxn1nu and NU-Foxn1nu/IkkβΔ double KO mice. Plots are representative of at least three animals per genotype. (G) Incidence of EAE in IkkβF/F (black line) and IkkβΔ (gray line) mice injected with MOG35–55 peptide (*P < 0.05 by log-rank test). (H) Proliferation of peripheral lymph node cells from IkkβF/F (black line) and IkkβΔ (gray line) mice restimulated with increasing amounts of MOG35–55 peptide 12 d after first exposure. Data are mean ± SE from at least three mice (**P < 0.01). (I and J) IL-17 and IFN-γ levels in supernatants from peripheral lymph node cells of IkkβF/F (black line) and IkkβΔ (gray line) mice 48 h after stimulation with increasing amounts of MOG35–55 peptide 12 d after first exposure. Data are mean ± SE from at least three mice (**P < 0.01).

Differentiation and expansion of IL-17–producing cells depends on IL-6, TGF-β, and IL-23 in addition to IL-1β (17, 21). Although we were not able to detect IL-23 or increased circulating TGF-β levels (Fig. S7A), IkkβΔ mice had elevated plasma IL-6 levels (Fig. 5C). Despite almost complete absence of IKKβ protein in liver, spleen, and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs; Fig. S7B), Il6 RNA levels were moderately increased in these cells (Fig. S7C), suggesting that this was a consequence of higher levels of circulating upstream cytokines, such as IL-1β (22) and possibly IL-17 itself (17), in these mice.

After we had confirmed sufficient IKKβ deletion in IkkβΔ MLNs, we wanted to rule out a cell-autonomous negative regulation by IKKβ during Th17 polarization. To this end, we purified peripheral CD4+ cells from WT mice and stimulated these with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 in the presence or absence of ML120B, along with IL-1β or IL-6, or in combination with TGF-β and IL-23. Because inhibition of IKKβ resulted in massive T-cell apoptosis after 72 h, we measured IL-17 production after 48 h when more than 80% of the cells remained alive. Although IL-1β alone was expectedly not sufficient to induce Th17 polarization of peripheral T cells, addition of IL-1β to the other cytokines resulted in a marked increase of IL-17 release compared with IL-6 stimulation alone or the combination of IL-6/TGF-β/IL-23; however, ML120B efficiently suppressed IL-17 production under all conditions (Fig. S7D). Comparable effects upon IKKβ inhibition could be observed when we induced Th17 polarization of naive thymic T cells, thereby confirming that loss of IKKβ function in T cells, per se, does not promote but even inhibits IL-17 production.

To examine whether granulocytosis in IkkβΔ mice was dependent on IL-17 or IL-1β elevation alone was sufficient to stimulate G-CSF and granulopoiesis, we took advantage of the peculiar situation that athymic nude mice (NU-Foxn1nu), in contrast to Rag1−/− mice, do not produce IL-17 (20). Inhibition of IKKβ did not impair IL-1β release in NU-Foxn1nu mice (Fig. S7E); however, as hypothesized, NU-Foxn1nu/IkkβΔ compound mutants lacked granulocytosis and splenomegaly, and their CD11b+/Gr-1+ neutrophil number in bone marrow was comparable to that in NU-Foxn1nu single mutants (Fig. 5 D–F). Furthermore, in accordance with an IL-17–dependent feedback amplification and a normal Il1r expression in NU-Foxn1nu mice, plasma IL-6 was no longer elevated in NU-Foxn1nu/IkkβΔ mice (Fig. S7 F and G). Nude mice obviously do not lack only IL-17, and therefore additional IL-17–independent effects could not be completely ruled out; however, because absence of mature T cells in Rag1−/− mice did not affect granulopoiesis, our results strongly suggest that it was the absence of IL-17 production that prevented neutrophilia in NU-Foxn1nu/IkkβΔ mice, rather than other secondary effects associated with the loss of T cells.

IkkβΔ Mice Are More Susceptible to Develop Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis.

Several autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and multiple sclerosis, are associated with dysregulated Th17 responses (23). Based on the central role of NF-κB in these diseases and the results in various animal models, inhibition of IKKβ has been suggested to represent a promising novel therapeutic strategy for many of these inflammatory conditions (24). In particular, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the most widely used animal model of multiple sclerosis, is driven by a myelin antigen-specific Th17 response (17, 25) yet CNS-restricted ablation of NF-κB signaling ameliorates EAE severity (26). We therefore wanted to examine how the particular phenotype of IkkβΔ mice would affect the outcome of EAE and whether inhibition of NF-κB or the strong Th17 response would prevail. Three weeks after injection of poly(I:C), when neutrophilia had fully developed in IkkβΔ mice, we immunized mutant mice and their control littermates with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) 35–55 (MOG35–55) emulsified in complete Freund adjuvant to induce an encephalitogenic T-cell response and monitored onset of disease. Full development of MOG35–55–induced EAE requires a pure C57BL/6 background. Because IkkβΔ and IkkβF/F controls were on a mixed genetic background, control mice were not susceptible to the challenge and did not develop clinical signs of EAE. In contrast, IkkβΔ mice already started to show the first signs of disease, such as limp tails or gait alterations, 1 wk after MOG35–55 immunization despite the mixed background, and within 3 wk, 50% of the KO animals developed EAE (Fig. 5G), suggesting that indeed the strong generation of a MOG35–55–specific Th17 response rendered Ikkβ-deficient animals highly susceptible to EAE development. To confirm the hyperreactivity of T cells in MOG35–55–immunized IkkβΔ mice, we isolated draining lymph node cells 12 d after immunization and examined their in vitro recall response to a secondary exposure to MOG35–55. Antigen-specific proliferation of T cells from MOG-immunized IkkβΔ mice and less from littermate controls could be stimulated in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5H). Furthermore, in contrast to control cells, restimulated IkkβΔ T cells secreted substantial amounts of IL-17 but not IFN-γ (Fig. 5 I and J), confirming the specificity of the enhanced Th17 response in MOG-immunized IkkβΔ mice.

Discussion

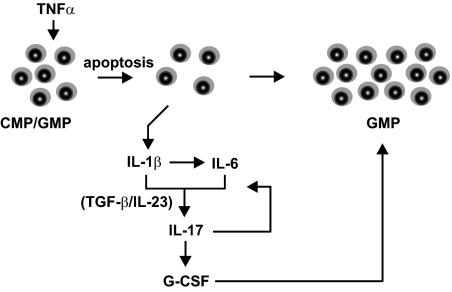

Loss of IKKβ function renders early B and T cells susceptible to TNF-α–induced apoptosis and thereby induces, over time, the loss of the adaptive immune system (6–8). In contrast, myeloid cell development does not seem to be impaired reflected by the massive granulocytosis, which has consistently been described to occur when IKKβ signaling is genetically or pharmacologically ablated (9). Now we demonstrate the unanticipated finding that, specifically, IKKβ-deficient myeloid progenitors also undergo rapid TNF-α–dependent apoptosis whereas mature bone marrow myeloid cells remain resistant in vivo. Interestingly, TNF-α levels were not elevated in IkkβΔ mice, suggesting that even the regular low levels of circulating TNF-α were sufficient to induce apoptosis. However, through the apoptosis-associated release of IL-1β, which triggers a complex cytokine cascade involving IL-17 and G-CSF, a compensatory feedback loop is initiated that assures survival of the myeloid lineage (Fig. 6). Because of persistent G-CSF up-regulation, myeloid progenitors can expand and continuously differentiate toward the neutrophil lineage, thus preserving the myeloid lineage and even overcompensating the initial loss. Although TNF-α induces apoptosis of both early lymphocytes and myeloid progenitors, a comparable regulatory mechanism to preserve adaptive immunity has not developed, with the remarkable exception of Th17-mediated immunity. Here, exaggerated availability of factors involved in the differentiation of Th17 cells appears to drive Th17 differentiation in the compartment of activated/memory T cells (27). This increases the risk of Th17-mediated organ-specific autoimmunity and also underscores the close relationship of Th17 immunity with innate immune responses (21, 28).

Fig. 6.

Schematic illustration summarizes the cytokine loop that causes neutrophilia in IkkβΔ mice. In response to normal levels of circulating TNF-α, Ikkβ-deficient myeloid progenitors (CMP and GMP) undergo rapid apoptosis and thereby release IL-1β, which leads to elevated plasma IL-6. Increased IL-1β and IL-6, together with physiological levels of TGF-β and IL-23, induce a Th17 polarization of CD4+ cells that is responsible for further amplification of IL-6 as well as the induction of G-CSF, which subsequently causes a compensatory expansion of GMP that ultimately culminates in granulocytosis.

Polarization of Th17 cells requires IL-6, IL-1β, IL-23, and TGF-β (23). Although IL-23 levels were not detectable at all and TGF-β was not elevated in IkkβΔ mice, both plasma IL-1β and IL-6 were markedly up-regulated in IkkβΔ mice. These results provide further evidence for the essential role of IL-1β in Th17 polarization (28, 29) and demonstrate that the oversupply of cytokines in vivo was sufficient to overcome lymphocyte apoptosis and induce a strong Th17 polarization of T cells in response to ambient antigens in vivo, although inhibition of IKKβ by ML120B was able to substantially block IL-17 production ex vivo. Furthermore, up-regulation of IL-17 supported the increase in plasma IL-6 as part of a feedback loop (17) together with IL-1β, despite the fact that IL-6 is transcriptionally controlled by NF-κB. In addition to the excessive amount of activating cytokines, presumably engagement of other transcription factors such as Stat3 (4) were also involved in elevated Il6 transcription.

Our results extend previous findings demonstrating a negative regulatory function of NF-κB in the processing of pro–IL-1β in LPS-stimulated differentiated macrophages and neutrophils (9). However, unlike in differentiated macrophages and neutrophils, in which caspase 1 or PR3 induce processing of pro–IL-1β, respectively, in myeloid progenitors, only caspase 1 contributes to release of IL-1β in an NLRP3 inflammasome-independent manner. Interestingly, ex vivo in the presence of ML120B, the two TLR agonists, LPS and Pam3Cys, induce CMP apoptosis to a similar extent as TNF-α. However, this may be an indirect effect mediated by TNF-α, as apoptosis cannot be observed when TNF signaling is blocked in Tnfr−/− cells (Fig. S8).

The development of granulocytosis associated with long-term inhibition of IKKβ represents a serious concern for the use of specific inhibitors in the treatment for chronic inflammatory diseases. In addition to increasing the susceptibility to endotoxin-induced shock (9), our data presented here suggest additional concerns about IL-17–mediated diseases. However, these could be limited to prolonged IKKβ inhibition, as IkkβΔ mice mimic chronic and high-dose IKKβ inhibition (6). Thus, it remains to be determined how short-term pharmacological inhibition would affect these inflammatory pathophysiologies. In contrast, the effects described here are unlikely to negatively affect patients with cancer treated with IKKβ inhibitors (4). Especially when these inhibitors are applied for short time periods to achieve sensitization to chemotherapy, such therapeutic strategies may well prove beneficial.

Materials and Methods

IKKβ-deficient mice were described previously (9). All animal procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines. Additional information on mouse strains as well as detailed information on flow cytometry, in vitro T cell differentiation, protein and RNA analysis, and induction of EAE can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kristin Retzlaff and Kerstin Burmeister for excellent technical assistance. We are grateful to Michael Karin, Vishva Dixit, and Dieter Jenne for generously providing IkkβF/F, Asc−/−, and Prtn3/Ela2−/− mice, respectively. We thank Wolf-Dietrich Hardt for providing Casp1−/− mice and Millenium Pharmaceuticals for providing ML120B. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants KO2964/2-1 (Heisenberg Program), KO2964/3-1 (to T.K.), and Gr1916/2-2 (Emmy-Noether Program; to F.R.G.); and by Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (AID-NET) (F.R.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1018331108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M. Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:693–733. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132:344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karin M, Greten FR. NF-kappaB: Linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:749–759. doi: 10.1038/nri1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bollrath J, Greten FR. IKK/NF-kappaB and STAT3 pathways: Central signalling hubs in inflammation-mediated tumour promotion and metastasis. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1314–1319. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baud V, Karin M. Is NF-kappaB a good target for cancer therapy? Hopes and pitfalls. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:33–40. doi: 10.1038/nrd2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagashima K, et al. Rapid TNFR1-dependent lymphocyte depletion in vivo with a selective chemical inhibitor of IKKbeta. Blood. 2006;107:4266–4273. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li ZW, Omori SA, Labuda T, Karin M, Rickert RC. IKK beta is required for peripheral B cell survival and proliferation. J Immunol. 2003;170:4630–4637. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.9.4630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senftleben U, Li ZW, Baud V, Karin M. IKKbeta is essential for protecting T cells from TNFalpha-induced apoptosis. Immunity. 2001;14:217–230. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greten FR, et al. NF-kappaB is a negative regulator of IL-1beta secretion as revealed by genetic and pharmacological inhibition of IKKbeta. Cell. 2007;130:918–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakai S, Aihara K, Hirai Y. Interleukin-1 potentiates granulopoiesis and thrombopoiesis by producing hematopoietic factors in vivo. Life Sci. 1989;45:585–591. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(89)90043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clausen BE, Burkhardt C, Reith W, Renkawitz R, Förster I. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res. 1999;8:265–277. doi: 10.1023/a:1008942828960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demetri GD, Griffin JD. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and its receptor. Blood. 1991;78:2791–2808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forlow SB, et al. Increased granulopoiesis through interleukin-17 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in leukocyte adhesion molecule-deficient mice. Blood. 2001;98:3309–3314. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rieger MA, Hoppe PS, Smejkal BM, Eitelhuber AC, Schroeder T. Hematopoietic cytokines can instruct lineage choice. Science. 2009;325:217–218. doi: 10.1126/science.1171461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung Y, et al. Critical regulation of early Th17 cell differentiation by interleukin-1 signaling. Immunity. 2009;30:576–587. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: Challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith E, et al. T-lineage cells require the thymus but not VDJ recombination to produce IL-17A and regulate granulopoiesis in vivo. J Immunol. 2009;183:5685–5693. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sutton CE, et al. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity. 2009;31:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miossec P, Korn T, Kuchroo VK. Interleukin-17 and type 17 helper T cells. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:888–898. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karin M, Yamamoto Y, Wang QM. The IKK NF-kappa B system: A treasure trove for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:17–26. doi: 10.1038/nrd1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kleinschek MA, et al. IL-25 regulates Th17 function in autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:161–170. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Loo G, et al. Inhibition of transcription factor NF-kappaB in the central nervous system ameliorates autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:954–961. doi: 10.1038/ni1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aggarwal S, Ghilardi N, Xie MH, de Sauvage FJ, Gurney AL. Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1910–1914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutton C, Brereton C, Keogh B, Mills KH, Lavelle EC. A crucial role for interleukin (IL)-1 in the induction of IL-17-producing T cells that mediate autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1685–1691. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gulen MF, et al. The receptor SIGIRR suppresses Th17 cell proliferation via inhibition of the interleukin-1 receptor pathway and mTOR kinase activation. Immunity. 2010;32:54–66. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.