Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

To determine whether the social environment surrounding lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth may contribute to their higher rates of suicide attempts, controlling for individual-level risk factors.

METHODS:

A total of 31 852 11th grade students (1413 [4.4%] lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals) in Oregon completed the Oregon Healthy Teens survey in 2006–2008. We created a composite index of the social environment in 34 counties, including (1) the proportion of same-sex couples, (2) the proportion of registered Democrats, (3) the presence of gay-straight alliances in schools, and (4) school policies (nondiscrimination and antibullying) that specifically protected lesbian, gay, and bisexual students.

RESULTS:

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth were significantly more likely to attempt suicide in the previous 12 months, compared with heterosexuals (21.5% vs 4.2%). Among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth, the risk of attempting suicide was 20% greater in unsupportive environments compared to supportive environments. A more supportive social environment was significantly associated with fewer suicide attempts, controlling for sociodemographic variables and multiple risk factors for suicide attempts, including depressive symptoms, binge drinking, peer victimization, and physical abuse by an adult (odds ratio: 0.97 [95% confidence interval: 0.96–0.99]).

CONCLUSIONS:

This study documents an association between an objective measure of the social environment and suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. The social environment appears to confer risk for suicide attempts over and above individual-level risk factors. These results have important implications for the development of policies and interventions to reduce sexual orientation–related disparities in suicide attempts.

Keywords: suicide attempts, sexual orientation, disparities, social determinants of health

WHAT'S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth attempt suicide at significantly higher rates than heterosexuals. The social environment may contribute to this elevated risk, but few empirical studies have used objective measures of the social environment to examine this hypothesis.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

This study demonstrated that negative characteristics of the social environment increase risk for suicide attempts among LGB youth, independent of individual-level risk factors. These results suggest that identifying structural interventions may help to reduce sexual orientation–related disparities in suicide attempts.

Over the past year, the topic of suicide among lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth has received increased media attention, after several recent suicides among gay youth in the United States.1 Overall, suicide is the third leading cause of death among youth aged 15 to 24 years,2 and LGB youth are more likely to attempt suicide compared with their heterosexual peers. This heightened risk for suicide attempts among LGB youth has been replicated across multiple sampling methodologies, including community3,4 and nationally representative5,6 surveys, and across different countries.7–9 Research into the underlying factors that may prevent suicide attempts among LGB youth is therefore a critical area for public health.

Both ecosocial10 and social stress11,12 theories have posited that the social conditions in which individuals are embedded confer risk for adverse health outcomes, suggesting that research focusing exclusively on individual-level risk factors (eg, depressive symptoms) can obscure important determinants of population health. For example, research has established that characteristics of the social environment, such as proportion of households with firearms, predict rates of completed suicide.13

Existing studies of LGB youth have identified a number of social factors associated with mental health and suicide attempts, including family and school connectedness,14 as well as school safety.5 These studies have provided important insights but have used self-reported measures of the social environment, which are confounded with mental health status.15 Measures of the social climate that do not rely on self-report are therefore needed to establish more accurate estimates of the association between environmental risk factors and suicide attempts. Previous research has documented associations between environmental measures (ie, presence of LGB campus resources) and health behaviors among LGB college students.16,17 With rare exception,18 however, studies have not linked an objectively defined (ie, non–self-report) index of the social environment to suicide attempts in LGB youth.

The current study sought to examine environmental correlates of suicide attempts among LGB youth, using a large (n = 31 852) population-based sample of youth. The 3 study aims were (1) to examine whether the association between the social environment and suicide attempts remains significant after controlling for well-established risk factors for suicide attempts at the individual level, including depressive symptoms,6,7 alcohol abuse,19,20 peer victimization,4,6 and physical abuse by an adult;21,22 (2) to determine whether the association between LGB status and suicide attempts differs as a function of the social environment surrounding LGB youth (ie, effect modification); and (3) to evaluate whether the social environment can explain or account for the association between LGB status and suicide attempts (ie, mediation).23

METHODS

Sample and Setting

Data were obtained from the Oregon Healthy Teens (OHT) study. Annual OHT surveys are administered to more than one-third of Oregon's 8th and 11th grade students attending public schools. Sexual orientation is only assessed in the survey of 11th graders. We pooled data from the years 2006 (when sexual orientation was first assessed) to 2008 (the most recent data) to increase the sample size of LGB participants. Nearly three-quarters (74.10%) of the school districts that were initially selected chose to participate in the OHT study, and 75.4% of the students in these schools participated in the OHT survey. Participating students came from 297 schools in 34 counties. The questionnaire was available in both English and Spanish. All participants were assured that the survey is anonymous and voluntary, and parents provided passive consent for their children to participate. Additional information on the OHT study can be found elsewhere.24

Measures

Demographic variables including sex and race/ethnicity were obtained via self-report. Sexual orientation was assessed with a single item asking respondents to indicate “which of the following best describes you.”4 Four response options were given: heterosexual (straight), gay or lesbian, bisexual, and not sure. Of 33 714 respondents, 30 439 (90.3%) self-identified as heterosexual, 301 (0.9%) self-identified as gay or lesbian, and 1112 (3.3%) self-identified as bisexual. We excluded 653 (1.9%) participants who indicated that they were “not sure” about their sexual orientation, consistent with previous studies.4 An additional 1209 respondents did not complete the sexual orientation item. Consequently, the final sample size was 31 852.

Independent Variable

Drawing on recent research on LGB community climate,25 we created an index of the social environment surrounding LGB youth, which was composed of 5 different items (described in more detail below): (1) proportion of same-sex couples living in the counties; (2) proportion of Democrats living in the counties; (3) proportion of schools with gay-straight alliances; (4) proportion of schools with antibullying policies specifically protecting LGB students; and (5) proportion of schools with antidiscrimination policies that included sexual orientation. Each of the 34 Oregon counties that were included in the 2006–2008 OHT surveys received a value for these 5 items.

Data on same-sex couples were obtained from the 2000 US Census,26 which includes a count of same-sex–partner households by county. The number of same-sex–partner households was divided by the total number of households in the county to create the proportion of same-sex couples living in each county.27 Data on monthly voter registration statistics were obtained from the Oregon Secretary of State Election Division.28 We calculated the average number of registered Democrats for the years between 2006 and 2008 and created a variable of the proportion of registered Democrats in each county. The number of gay-straight alliances in each school district was obtained from the Gay and Lesbian Education Network29; we created a variable of the proportion of schools within each district that had a gay-straight alliance.

Data on school antidiscrimination and antibullying policies were obtained from the Oregon Department of Education.30 Policies had to include the phrase “sexual orientation” (eg, in a list of protected class statuses) to be considered as protecting LGB youth. The OHT study does not release data on the individual schools that participated in the survey. Consequently, we created a variable of the proportion of schools within each of the Oregon school districts that had antibullying and nondiscrimination policies related to sexual orientation. Of 197 districts in Oregon, no information was available for 18 districts, which were coded as missing. To ensure that all social-environment variables were consistent geographically, the 3 school measures (ie, gay-straight alliances, antibullying policies, and antidiscrimination policies) were aggregated to the county level by dividing the number of schools with gay-straight alliances and protective policies by the total number of school districts in the county.

A factor analysis indicated that these 5 items loaded onto a single factor (factor loadings ranged from 0.50 to 0.85) that explained 55.67% of the variance in social climate; the items demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.79). Consequently, these values were summed to create an index of the extent to which the social environment was supportive of gays and lesbians in that county. On the basis of the mean of this sum, we created a z score reflecting the deviation of the value from the mean; the z scores ranged from −10.29 to 6.24 (mean: 0.0, SD: 3.7). A value of 2.0 for the social-environment variable means that the value for that county is 2 SDs above the overall mean (ie, is more supportive of gays and lesbians). Previous research using a similar measure of LGB climate found a strong correlation (r = 0.35, P < .001) with LGB adults' perceptions of how supportive their communities were,25 providing support for the validity of our measure.

Outcome Variable

Participants were asked the number of times they attempted suicide during the past 12 months. Given the nonnormal distribution, suicide attempts were examined as a dichotomous outcome. The suicide question used in the OHT study was based on a measure from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance Survey, which showed excellent test-retest reliability (κ = 76.4).31

Covariates

The OHT survey included several measures of well-established predictors of suicide attempts.31,32 Depressive symptoms were assessed with the following question: “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?” Binge drinking was assessed via a single item: “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you have 5 or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple of hours?” Peer victimization was assessed by asking respondents whether they had been harassed at school (or on the way to or from school) in the past 30 days. Physical abuse was assessed with the following question: “During your life, has any adult ever intentionally hit or physically hurt you?” Response items for all covariates were dichotomous.

Statistical Analysis

The analytic strategy consisted of 4 steps. First, we tested for differences in suicide attempts and risk factors between LGB and heterosexual youth using basic descriptive cross-tabulations. Second, we examined whether the social environment was significantly associated with suicide attempts after adjusting for multiple individual-level risk factors for suicide attempts, using generalized estimating equations.33 Generalized estimating equation is a method developed for handling clustered data, in which the observations within each cluster are correlated with each other. Given that OHT respondents were nested within their county of residence, we used generalized estimating equations to account for the correlations among observations from each individual within the same county. Third, we tested whether the effect of the social environment on suicide attempts varies by sexual orientation using multiplicative interaction terms in the generalized estimating equation model. Fourth, mediation was evaluated by examining a reduction in the association between LGB status and suicide attempts after adjusting for the measure of the social environment. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05.

RESULTS

The sociodemographic information of the 2006–2008 OHT sample, stratified by sexual orientation, is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the OHT Sample, by Self-Reported Sexual Orientation, 2006–2008

| Characteristics | Self-Identified Lesbian or Gay, n = 301, n (%) | Self-Identified Bisexual, n = 1112, n (%) | Self-Identified Heterosexual, n = 30 439, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 183 (60.80) | 278 (25.0) | 15 076 (49.53) |

| Female | 118 (39.20) | 834 (75.0) | 15 363 (50.47) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 219 (72.76) | 812 (73.02) | 22 368 (73.48) |

| Black | 9 (2.99) | 23 (2.07) | 628 (2.06) |

| Native American | 10 (3.32) | 42 (3.78) | 741 (2.43) |

| Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 4 (1.33) | 13 (1.17) | 447 (1.47) |

| Asian | 11 (3.65) | 29 (2.61) | 1120 (3.68) |

| Hispanic | 5 (1.66) | 16 (1.44) | 927 (3.05) |

| Multiethnic | 18 (5.98) | 124 (11.15) | 2167 (7.12) |

| Missing/chose not to respond | 25 (8.31) | 53 (4.77) | 2041 (6.71) |

LGB respondents were significantly more likely to have attempted suicide in the past 12 months than heterosexuals (Table 2). Nearly 20% of lesbian and gay youth, and 22% of bisexual youth, attempted suicide at least once in the previous 12 months, compared with 4% of their heterosexual peers. LGB youth also had significantly higher levels of all 4 established risk factors for suicide attempts, compared with heterosexual youth.

TABLE 2.

Disparities in Suicide Attempts and Risk Factors, by Self-Reported Sexual Orientation: the OHT Study, 2006–2008

| Self-Identified Lesbian or Gay, n = 301, n (%) | Self-Identified Bisexual, n = 1112, n (%) | Self-Identified Heterosexual, n = 30 439, n (%) | Group Differences, df = 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicide attempts in past 12 months | ||||

| At least 1 attempt | 59 (19.60) | 245 (22.03) | 1280 (4.21) | F = 427.70a |

| Risk factors for suicide attempts | ||||

| Depressive symptoms in past 12 months | 108 (35.88) | 499 (40.38) | 5192 (17.06) | F = 331.25a |

| Binge drinking in past 30 days | 81 (26.91) | 362 (32.55) | 7862 (25.83) | F = 15.42a |

| Peer victimization in past 30 days | 177 (58.80) | 620 (55.76) | 8625 (28.34) | F = 264.42a |

| Adult physical abuse in lifetime | 96 (31.89) | 561 (50.45) | 8353 (27.44) | F = 159.87a |

All risk factors for suicide attempts are dichotomous. Group differences were evaluated using analysis of variance.

P < .001.

Next, we ran multivariate generalized estimating equation models to examine the association between the social environment and suicide attempts. Because the 3-way interaction (gender × LGB status × social environment) was not significant (P > .05), the remaining analyses were run with the full sample. In the unadjusted model, the social environment was significantly associated with suicide attempts (odds ratio [OR]: 0.98 [95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.97–0.99]). In the model adjusted for demographics (gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation), the social environment remained significantly associated with suicide attempts (OR: 0.97 [95% CI: 0.95–0.98]). In the final model adjusted for demographics as well as all 4 covariates (Table 3), the social environment continued to be significantly associated with suicide attempts (OR: 0.97 [95% CI: 0.96–0.99]). To capture variability in the social environment surrounding LGB youth, the social environment was entered as a continuous variable; hence, an OR of 0.97 is associated with a 1-unit difference in the social-environment measure (which has a 17-point range). When the social environment measure was dichotomized (1 SD above and below the mean), the OR increased in magnitude (OR: 0.76 [95% CI: 0.61–0.95]), indicating that those living in positive environments are less likely to attempt suicide compared with those living in negative environments.

TABLE 3.

Association Between the Social Environment and Suicide Attempts

| Parameters | OR (SE) | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social environment | 0.97 (0.01) | (0.96–0.99) | .013 |

| Lesbian/gay | 3.48 (.21) | (2.33–5.20) | <.001 |

| Bisexual | 2.82 (.10) | (2.32–3.42) | <.001 |

| Sex | 0.77 (.07) | (0.67–0.87) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.61 (.07) | (0.53–0.70) | <.001 |

| Depressive symptoms | 8.37 (.07) | (7.33–9.55) | <.001 |

| Binge drinking | 1.62 (.06) | (1.43–1.83) | <.001 |

| Peer victimization | 1.89 (.07) | (1.67–2.15) | <.001 |

| Adult physical abuse | 2.12 (.06) | (1.87–2.41) | <.001 |

Final generalized estimating equation model predicting suicide attempts in the past 12 months. Social environment was entered as a continuous predictor (range: −10.29 to 6.24). Sex: female = 1; male = 0. Race/ethnicity: white = 1; other = 0. Depressive symptoms, binge drinking, victimization, and physical abuse are all dichotomous covariates (0 = no depressive symptoms in past 12 months, no binge drinking in past 30 days, no peer victimization in past 30 days, and no adult physical abuse in lifetime).

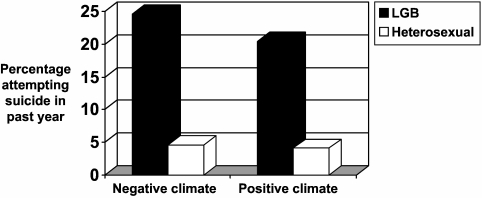

The interaction between LGB status and the social environment was not statistically significant. However, an examination of the prevalence of suicide attempts revealed that the probability of suicide attempts differs markedly as a function of the social environment (Fig 1). Among LGB youth, the risk of attempting suicide was 20% greater in negative environments compared with positive environments (25.47% of LGB living in negative environments attempted suicide at least once versus 20.37% in positive environments). In contrast, among heterosexual youth, the risk of suicide attempts was only 9% greater in negative environments.

FIGURE 1.

Relationship between social climate and suicide attempts. In this analysis, social climate was divided at the median, with those below the median residing in a negative climate for LGB youth and those above the median residing in a positive climate.

Finally, we examined whether the social environment mediates the association between sexual orientation and suicide attempts. In the unadjusted model, LGB status was a significant predictor of suicide attempts (lesbian or gay: OR: 5.99 [95% CI: 4.48–8.04]; bisexual: OR: 6.60 [95% CI: 5.67–7.70]). In the final adjusted model that included the social environment and individual-level risk factors (Table 3), LGB status remained a significant predictor of suicide attempts, but the OR was reduced by 42% for lesbian and gay youth and 57% for bisexual youth.

DISCUSSION

The current study used a novel measure of the social environment that did not rely on self-report perceptions and linked this measure to suicide attempts in a population-based sample of youth. Results indicated that living in environments that are less supportive of gays and lesbians is associated with greater suicide attempts among LGB youth. Previous studies have documented several factors that increase the risk for suicide attempts among LGB youth, including depression,7 peer victimization,4 hazardous alcohol use,6 and physical abuse by an adult.21 Even after adjusting for these individual-level risk factors, the social environment was associated with suicide attempts in this sample.

There also was a reduction in the association between sexual orientation and suicide attempts when the social environment and individual-level risk factors were controlled. This attenuation (42% for lesbian and gay youth and 57% for bisexual youth) was larger than that found in previous studies, which have ranged from 8%7 to 30%.6 Although this reduction was largely driven by the individual-level risk factors (the social environment accounted for an additional 2% reduction in the association between sexual orientation and suicide attempts), on a population level these effects can have a significant public health impact. For instance, a 5-unit increase in the social-environment measure, which is plausible given the 17-point range of this measure, would lead to a 10% reduction in suicide attempts.

It is important to note, however, that LGB status remained a significant predictor of suicide attempts even after adjusting for individual-level and social-level risk factors. One possibility for the lack of full mediation is that the social climate variable was not an exhaustive index of the ecological environment for Oregon youth. Indeed, there are other contextual effects (eg, antigay attitudes) that were not included in the measure that may be associated with suicide attempts. Moreover, the OHT survey does not include measures of risk factors that are unique to LGB individuals, such as gay-related stressors34 and earlier age at disclosure,35 which are associated with suicidality. Studies that incorporate additional measures of the social context and gay-specific risk factors are needed to further test mediational hypotheses.

Future research also is needed to identify mechanisms linking aspects of harmful social environments to suicide attempts among LGB youth. One potential pathway is through increased exposure to status-based stressors, a well-documented risk factor for poor mental health in LGB populations.11 For example, LGB adults living in states in which they are denied legal protection report multiple stressors, including negative media portrayals, antigay graffiti, comments, and jokes, and a lost sense of safety.36 Stress contributes to the development of psychopathology,37,38 which in turn increases the risk of suicide attempts. Recent research also has suggested that the social environment may contribute to adverse mental health outcomes among LGB individuals through creating elevations in basic psychological risk factors for psychopathology, such as emotion regulation difficulties,39 which are associated with suicidality.40

This study has several limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional. Consequently, we cannot infer causal relationships between the social environment and suicide attempts. Prospective studies that examine how the social environment influences suicide attempts are needed to establish clearer causal inferences. Second, the OHT study only assesses youth attending schools; consequently, runaway or homeless youth are not included. Because LGB individuals are overrepresented among homeless youth,41 the OHT study may be missing a vulnerable subpopulation of LGB youth. Nevertheless, a negative social environment is likely to be a particularly robust determinant of suicide attempts among LGB homeless youth, which would have biased our results toward the null. Third, although the OHT study surveyed over one-third of youth attending public schools in Oregon, students attending private and alternative schools were not included. In addition, one-quarter of school districts declined to participate in the study. Both of these factors likely restrict the generalizability of the study's results. Future studies are therefore needed to replicate these findings using other samples of youths from diverse social contexts. Fourth, although the OHT measures have been well validated,31,32 some weaknesses of the measures have been noted, including single-item measures that may inflate the actual prevalence of suicide attempts.42 These results require replication with more detailed assessments of suicide attempts.

There also were limitations to the school policy variables. The OHT study does not release data on the specific schools that participated in the survey. The variables on school policies were aggregated across the district level and are therefore less sensitive indicators than measures of individual school policies. This likely reduced our ability to detect stronger relationships between the social environment and suicide attempts. Moreover, although the school policies represent a marker of school climate, we were unable to obtain data regarding the extent to which these policies were enforced in the schools. In addition, 18 school districts did not provide information on school policies; consequently, the school climate variables for these counties were less reliable. However, when the 4 counties with missing data were removed from the analyses, the results remained unchanged. Finally, although counties are much smaller spatial units than states, they may not reflect all aspects of community climate.43 Creating measures of ecological environments that are more proximal to LGB youth (eg, neighborhoods) will provide an opportunity to test the sensitivity of this study's results across different spatial scales,44 an important avenue for future inquiry. Nevertheless, the fact that we were able to document an association between social climate at the county-level and suicide attempts suggests that the results should be considered conservative estimates.

The current study has several noteworthy advantages for studying relationships between environmental risk factors and suicide attempts. The large, population-based sample permitted the opportunity to separate lesbians and gays from bisexual youth in the statistical analyses. The LGB and heterosexual participants were recruited using identical sampling methods. Many previous studies45 have recruited LGB respondents from different venues than heterosexuals, which may introduce sampling biases.46 An additional methodological strength is our objective measure of the social environment. Previous studies have used self-report measures of the environment, such as perceived discrimination.47 These subjective measures may capture how LGB individuals construe their experience of living in harmful social environments, but such measures are confounded with mental health status.15 In contrast, our index of the social environment occurred outside the control of the individual and could not be caused by individual-level factors that also might affect the dependent variable, which helps to minimize endogeneity. Finally, many studies using ecological data suffer from the “ecological fallacy” when they try to extrapolate from aggregated data to individuals.48 However, a strength of the current study was the assessment of suicide attempts on the individual level, thus linking the ecologic with the individual level and avoiding incorrect inference across levels.49

CONCLUSIONS

One of the central goals of Healthy People 201050 was the elimination of health disparities among socially disadvantaged groups. It is evident that this goal has not been fully realized with LGB populations. The current study demonstrated that characteristics of the social environment increase the risk for suicide attempts among LGB youth, over and above individual-level risk factors. Additional research on the social determinants of mental health among LGB youth could provide a greater understanding of the etiology of sexual orientation-related disparities in suicide attempts and may ultimately facilitate the development of suicide-prevention programs that seek to reduce these disparities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by The Center for Population Research in LGBT Health at The Fenway Institute and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (award no R21HD051178).

The author wishes to thank the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholars program for its financial support.

The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Mark L. Hatzenbuehler is a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholar at Columbia University in New York City.

Mark L. Hatzenbuehler originated the study idea, completed the analyses, and wrote the article. Mark L. Hatzenbuehler had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The author has indicated that he has no personal financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

- LGB

- lesbian, gay, and bisexual

- OHT

- Oregon Healthy Teens

- OR

- odds ratio

- CI

- confidence interval

REFERENCES

- 1. Rovzar C. (2010, September 30). Tyler Clementi's suicide: more than cyber-bullying. New York Magazine. Daily Intel, Post 36. Available at: http://nymag.com/daily/intel/2010/09/post_36.html Accessed March 16, 2011

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [article online]. Available at: //www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html Accessed March 16, 2011

- 3. Remafedi G, French S, Story M, Resnick MD, Blum R. The relationship between suicide risk and sexual orientation: results of a population-based study. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(1):57–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Kessel S, Palfrey J, DuRant RH. The association between health risk behaviors and sexual orientation among a school-based sample of adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(5):895–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eisenberg ME, Resnick MD. Suicidality among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youth: the role of protective factors. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(5):662–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Russell ST, Joyner K. Adolescent sexual orientation and suicide risk: evidence from a national study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1276–1281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wichstrøm L, Hegna K. Sexual orientation and suicide attempt: a longitudinal sample of the general Norwegian sample. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(1):144–151 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Beautrais AL. Is sexual orientation related to mental health problems and suicidality in young people? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(10):876–880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewis NM. Mental health in sexual minorities: recent indicators, trends, and their relationships to place in North America and Europe. Health Place. 2009;15(4):1029–1045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(4):668–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC. The sociology of mental health. In Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC. eds. Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health. New York, NY: Springer; 1999, pp 3–18 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Household firearm ownership and suicide rates in the United States. Epidemiology. 2002;13(5):517–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saewyc EM, Homma Y, Skay CL, Bearinger LH, Resnick MD, Reis E. Protective factors in the lives of bisexual adolescents in North America. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(1):110–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meyer IH. Prejudice as stress: conceptual and measurement issues. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):262–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eisenberg ME. The association of campus resources for gay, lesbian, and bisexual students with college students' condom use. J Am Coll Health. 2002;51(3):109–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eisenberg ME, Wechsler H. Social influences on substance-use behaviors of gay, lesbian, and bisexual college students: findings from a national study. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(10):1913–1923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walls NE, Freedenthal S, Wisneski H. Suicidal ideation and attempts among sexual minority youths receiving social services. Social Work. 2008;53(1):21–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Swahn MH, Bossarte RM. Gender, early alcohol use, and suicide ideation and attempts: findings from the 2005 youth risk behavior survey. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41(2):175–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fleming TM, Merry SN, Robinson EM, Denny SJ, Watson PD. Self-reported suicide attempts and associated risk and protective factors among secondary school students in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41(3):213–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ystgaard M, Hestetun I, Loeb M, Mehlum L. Is there a specific relationship between childhood sexual and physical abuse and repeated suicidal behavior? Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28(8):863–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Greenland S, Seeman TE. Age of minority sexual orientation development and risk of childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts in women. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(4):511–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kazdin AE. Research Design in Clinical Psychology. Boston, MA: Allen and Bacon; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oregon Youth Risk Behavior Survey [Web page]. Available at: www.dhs.state.or.us/dhs/ph/chs/youthsurvey/ohteens/2007/county/index.shtml Accessed Aug 19, 2010

- 25. Oswald RF, Cutherbertson C, Lazarevic V, Goldberg AE. New developments in the field: measuring community climate. J LGBT Fam Stud. 2010;6(2):214–228 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Community Marketing CMI's gay & lesbian community survey [article online]. Available at: www.gaydemographics.org Accessed March 16, 2011

- 27. Romero AP, Rosky CJ, Badgett MVL, Gates GJ. Census Snapshot: Oregon. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oregon Secretary of State Division of Elections [Web page]. Available at: www.sos.state.or.us/elections/votreg/regpart.htm Accessed Aug 19, 2010

- 29. Gay and Lesbian Education Network [Web site]. www.glsen.org/cgi-bin/iowa/all/home/index.html Accessed Aug 19, 2010

- 30. Oregon Department of Education [Web site]. www.ode.state.or.us Accessed Aug 19, 2010

- 31. Brener N, Collins J, Kann L, Warren C, Williams B. Reliability of the youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;141(6):575–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, Kinchen SA, Sundberg EC, Ross JG. Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(4):336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Diggle PJ, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rosario M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Reid H. Gay-related stress and its correlates among gay and bisexual male adolescents of predominantly Black and Hispanic background. J Community Psychol. 1996;24(2):136–159 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Suicide attempts among sexual-minority male youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(4):509–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Russell GM, Richards JA. Stressor and resilience factors for lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals confronting anti-gay politics. Am J Community Psychol. 2003;31(3–4):313–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brown GW. Life events and affective disorder: replications and limitations. Psychosom Med. 1993;55(3):248–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dohrenwend BP. The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: some evidence and its implications for theory and research. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(1):1–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin?” A psychological mediation framework. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(5):707–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Linehan MM. Skills Training Manual for Treating Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cochran BN, Stewart AJ, Ginzler JA, Cauce AM. Challenges faced by homeless sexual minorities: comparison of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender homeless adolescents with their heterosexual counterparts. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):773–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Savin-Williams RC. Suicide attempts among sexual-minority youths: population and measurement issues. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(6):983–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Messer LC. Invited commentary: beyond the metrics for measuring neighborhood effects. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(8):868–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Diez Roux AV. Neighborhoods and health: where are we and were do we go from here? Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2007;55(1):13–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Safren SA, Heimberg RG. Depression, hopelessness, suicidality, and related factors in sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(6):859–866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Diamond LM. New paradigms for research on heterosexual and sexual-minority development. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(4):490–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mays VM, Cochran SD. Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1869–1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Robinson WS. Ecological correlations and the behavior of individuals. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38(2):337–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schwartz S. The fallacy of the ecological fallacy: the potential misuse of a concept and the consequences. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(5):819–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. US Department of Health and Human Services Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000 [Google Scholar]