Abstract

Aldosterone (Aldo) causes podocyte damage by an unknown mechanism. We examined the role of mitochondrial dysfunction (MtD) in Aldo-treated podocytes in vitro and in vivo. Exposure of podocytes to Aldo reduced nephrin expression dose dependently, accompanied by increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The ROS generation and podocyte damage were abolished by the mitochondrial (mt) respiratory chain complex I inhibitor rotenone. Pronounced MtD, including reduced mt membrane potential, ATP levels, and mtDNA copy number were seen in Aldo-treated podocytes and in the glomeruli of Aldo-infused mice. The mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist eplerenone significantly inhibited Aldo-induced MtD. The MtD was associated with higher levels of ROS, reduction in the activity of complexes I, III, and IV, and expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) coactivator-1α and mt transcription factor A. Both the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone and PPARγ overexpression protected against podocyte injury by preventing MtD and oxidative stress, as evidenced by reduced ROS production, by maintenance of mt morphology, by restoration of mtDNA copy number, by decrease in mt membrane potential loss, and by recovery of mt electron transport function. The protective effect of rosiglitazone was abrogated by the specific PPARγ small interference RNA, but not a control small interference RNA. We conclude that MtD is involved in Aldo-induced podocyte injury, and that the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone may protect podocytes from this injury by improving mitochondrial function.

The mineralocorticoid aldosterone (Aldo) is a key component of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and is increasingly recognized as an important player in the development and progression of kidney disease. Patients with chronic kidney disease have markedly elevated plasma Aldo concentrations. Animal studies suggest that Aldo is a pathogenic factor in renal injury in the remnant kidney of hypertensive rats,1 and in renal fibrosis. Moreover, exogenous infusion of Aldo reverses the renoprotective effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in hypertensive remnant kidney rats, and in stroke-prone, spontaneously hypertensive rats.2 In vitro studies show that Aldo exerts a direct deleterious influence on kidney cells, including podocytes,3–5 mesangial cells, proximal tubular epithelial cells,6 and fibroblasts. In particular, Aldo causes podocyte injury in vivo and in vitro, and Aldo blockade is therapeutic in renal injury.5,7–9 However, the underlying mechanism for Aldo-induced injury in the kidney (in general) and in the podocytes (in particular) is not well understood.

Podocytes are terminally differentiated, high-energy required cells that have lost mitotic activity, and typically do not proliferate after injury.10 Mitochondria (mt) dysfunction (MtD) is involved in several diseases and progressive disease processes, including glomerulosclerosis, in which podocyte injury is a crucial event in sclerosis formation.11,12 We hypothesized that preserving mt function is important for preventing podocyte injury.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are nuclear hormone receptors and ligand-activated transcription factors.13 Among these, PPARγ is the target of thiazolidinediones, which are widely used as an insulin sensitizer in patients with type 2 diabetes. PPARγ agonists may have renoprotective effects in diabetic nephropathy, chronic renal insufficiency, and renal transplantation.13 In particular, PPARγ agonist pioglitazone is protective in podocyte injury-associated sclerosis, possibly by inhibiting podocyte apoptosis and macrophage infiltration, increasing VEGF expression and protecting against glomerular capillary loss.14 However, little is known about the mechanism of action of PPARγ in podocytes. On the other hand, PPARγ agonists induce mt biogenesis and oxidative metabolism,15,16 and protect against neurodegeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by increasing mt function.17,18

Our previous study showed that Aldo-induced renal proximal tubular epithelial cell injury was mediated by mt reactive oxygen species (ROS).6 We postulated that the same mediator (ie, mt ROS) may contribute to Aldo-induced podocyte injury and may serve as a therapeutic target of PPARγ agonists in renal diseases. Therefore, the present study was designed to test whether Aldo induced mt injury and ROS generation and PPARγ protects against the Aldo effects in in vivo and in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Reagents, Plasmid, and Antibodies

Aldosterone, rosiglitazone, rotenone, and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Eplerenone was from Pfizer Co., Ltd. (New York, NY). Primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies were against nephrin and podocin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator (PGC)-1α and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), and PPARγ (Bioworld, Minneapolis, MN). Peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The PPARγ expression plasmid (pcDNA3.1-PPARγ) was from Addgene (Addgene Inc., Cambridge, MA). The specific PPARγ small interference RNA (siRNA) and the negative control siRNA were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell Culture

MPC5 conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte clonal cells (kindly provided by Peter Mundel at Mount Sinai School of Medicine through Dr. Jie Ding at Peking University, Beijing, China) were cultured and induced to differentiate as described.19 Briefly, podocytes were grown and propagated at 33°C in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 10 U/mL interferon-γ (Peprotech Inc, Rocky Hill, NJ). To induce differentiation, cells were plated in type I collagen-coated flasks under nonpermissive conditions (37°C without interferon-γ) for 7 to 10 days. Fully differentiated podocytes were cultured for 7 to 10 days at 37°C (to 50% to 60% confluence) and treated with Aldo in the presence or absence of rosiglitazone or rotenone.

Transient Transfection

Transfection was performed essentially as described.20 Podocytes were cultivated to 60% to 70% confluence in culture medium containing no penicillin or streptomycin. pcDNA3.1-PPARγ (5 μg) and PPARγ and control siRNA (80 nmol/L) were transfected with Vigofect reagent (Vigorous Biotechnology, Inc., Beijing, China) and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), respectively, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Four hours after transfection, 1 mL of basic cell culture medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum was added to each well. Cells were cultured for an additional 24 hours before Aldo treatment.

Mice

The 8-week-old male C57BL/6J mice (weight, 20 g to 25 g) were implanted subcutaneously with 14-day release osmotic mini-pumps (Duret Corp., Cupertino, CA) by incision of the right flank region under light 3% isoflurane anesthesia. Aldo was infused at 90 ng/day for 2 weeks. After 7 days, Aldo-treated animals received vehicle or rosiglitazone (10 mg/kg per day by gavage) for 7 days. All mice were on standard pelleted rodent chow and housed in an air-conditioned room with a 12:12 hours ration of light-dark cycles. Mice were placed in metabolic cages before the end of the treatment for a 24-hour urine sample. On day 14, under nathesia, plasma and various tissues were harvested. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. All animal procedures were approved by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Isolation of Glomeruli and Mitochondria

Isolation of glomeruli was performed as previously reported.21 Mt from glomeruli were isolated using a kit from Sigma (MITO-ISO1, Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) using the manufacturer's protocol. Isolated mt were re-suspended in storage buffer and protein concentration, which was determined by the Bradford method.

PCR

Total DNA and RNA from cultured podocytes and isolated glomeruli were extracted by a DNeasy Tissue Kit (QIAGEN Sciences, Germantown, MD), and Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), respectively. Oligonucleotides (Table 1) were designed by Primer3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu, last accessed September 2009) and synthesized by Invitrogen.

Table 1.

Sequence of Primer Pairs for Quantitative Real-Time PCR

| Name | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | 5'-GTCTTCACTACCATGGAGAAGG-3' | 5'-TCATGGATGACCTTGGCCAG-3' |

| Nephrin | 5'-CCCAGGTACACAGAGCACAA-3' | 5'-CTCACGCTCACAACCTTCAG-3' |

| TFAM | 5'-GGAATGTGGAGCGTGCTAAAA-3' | 5'-TGCTGGAAAAACACTTCGGAATA-3' |

| mtDNA | 5'-TTTTATCTGCATCTGAGTTTAATCCTGT-3' | 5'-CCACTTCATCTTACCATTTATTATCGC-3' |

| 18s rRNA | 5'-GGACCTGGAACTGGCAACAT-3' | 5'-GCCCTGAACTCTTTTGTGAAG-3' |

| Podocin | 5'-GTGAGGAGGGCACGGAAG-3' | 5'-AGGGAGGCGAGGACAAGA-3' |

| PPAR-γ | 5'-CTGGCCTCCCTGATGAATAA-3' | 5'-GGCGGTCTCCACTGAGAATA-3' |

GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; mt, mitochondrial; PPAR, peroxisome proliferators activated receptor; TFAM, mitochondrial transcription factor A.

Real-time PCR was performed for detection of mtDNA copy number and target gene expression. Real-time PCR amplification was performed using an ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR Detection System with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Cycling conditions were 95°C for 10 minutes followed by 40 repeats of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. Relative amounts of mtDNA copy number were normalized to the nuclear 18S rRNA gene, and mRNA was normalized to GAPDH, and were calculated using the δ-delta method from threshold cycle numbers.

Western Blotting

Podocytes or isolated glomeruli were lysed in protein lysis buffer (50 mmol/L Tris, 150 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 200 mmol/L sodium fluoride, 4 mmol/L sodium orthovanadate as protease inhibitors, pH 7.5) for 15 minutes on ice. Protein concentration was measured as previously described. Immunoblotting was performed as previously described.6

ROS Production

Podocyte ROS production was measured as previously described.22 Kidney ROS production was measured in frozen kidney sections embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature embedding medium,. Sections were covered with 10 μmol/L 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate and incubated in the dark at 37°C for 30 minutes. Slides were washed in PBS for 5 minutes and mounted with VectaShield Mounting Media for Fluorescence (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were acquired with a Leica microscope (DM5000) with a Q-Imaging digital camera (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) under fluorescent light. Quantification was made as pixel density from 40 random images per group using MetaMorph software (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA).

For isolated mt ROS levels, mt pellets were re-suspended in HEPES-saline buffer (pH 7.4) (10 mmol/L HEPES, 140 mmol/L NaCl, 5 mmol/L KCl, 1.2 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 5 mmol/L NaHCO3, 6 mmol/L glucose, 1 mmol/L MgCl2, 2 mmol/L CaCl2), and 140 μL of HEPES-saline buffer added to each well of a fluorescence microtiter plate, followed by 10 μl of sample and 50 μL of 2′,7′ dichlorfluorescein diacetate (DCFHDA) (final concentration 10 μmol/L). Plates were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 30 minutes and analyzed (excitation 485 nm/emission 520 nm) on a FLUOstar Optima - Fluorescence plate Reader (Offenberg, Germany). Data are expressed as fluorescence units per mg protein.

Kidney Histology

Kidney tissue from mice was immersion-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS solution and was routinely processed, and 3-μm sections were stained with PAS or H&E. All sections were examined by individuals blinded to treatment protocol.

Electron Microscopy

Podocytes were collected after trypsin digestion, and were dissected and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde buffer (pH 7.4). Fresh kidney tissues were fixed in 5% glutaraldehyde buffer (pH 7.4). Both cells and kidney tissues were prepared as described.23 Ultrathin sections (60 nm) were cut on a microtome, placed on copper grids, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and were examined in an electron microscope (JEOL JEM-1010, Tokyo, Japan).

MMP Analysis

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was determined using a lipophilic cationic probe 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimdazol carbocyanine iodide (JC-1; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as described.24 Briefly, the mt pellet and dissociated podocytes were washed twice with Hank's balanced salt solution (Sigma), and incubated in the dark with JC-1 (7.5 μmol/L; 30 minutes at 37°C). Mt and cells were washed with JC-1 washing buffer, and fluorescence was detected by fluorescence-assisted cell sorting for podocytes, or a FLUOstar Optima - Fluorescence plate Reader for isolated mt. Relative MMP was calculated using the ratio of J-aggregate/monomer (590 nm/520 nm). Values are expressed as fold-increase in J-aggregate/monomer fluorescence over control cells.

ATP and mt Enzymes

ATP levels were determined with a luciferase-based bioluminescence assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in a FLUOstar Optima - Fluorescence plate Reader, according to the manufacturer's instructions. The specific activity of complexes I, II, III, and IV in isolated glomeruli was measured as described.25 Enzymatic activities are expressed as nanomoles per minute per milligram protein.

Glomerular Lipid Peroxides and Urinary Albumin and F2-Isoprostane Analysis

Levels of lipid peroxide (malondialdehyde content) were assessed in isolated glomeruli by lipid extraction and spectrophotometric measurement of thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances using 1,2,3,3-tetramethoxypropane as the standard. Results are expressed as nanomoles per milligram of protein.

EIA kits (Exocell, Philadelphia, PA) determined urinary concentrations of albumin and F2-isoprostane (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI), according to the instructions. For all assays, samples were run in duplicate and the results were averaged.

Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical analysis used one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni's test, using SPSS 11.5 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). P < 0.05 was significant.

Results

Rosiglitazone Effects on Nephrin Expression

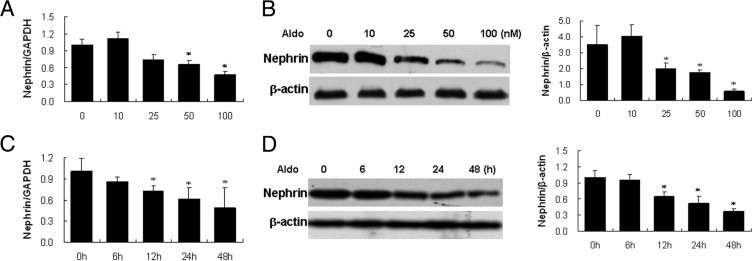

We first investigated the effect of Aldo on nephrin expression in cultured podocytes. Podocytes were exposed to 0–100 nmol/L of Aldo, which is dose dependently, reduced nephrin mRNA and protein expression with a noticeable effect at 50 nmol/L and a maximal effect at 100 nmol/L (Figure 1, A and B). A time-course of nephrin expression after 100 nmol/L Aldo showed that effects were time-dependent (Figure 1, C and D).

Figure 1.

Effect of aldosterone (Aldo) on nephrin expression in podocytes. (A, B). Podocytes were treated with the indicated doses of Aldo for 48 hours, and nephrin mRNA and protein expression were detected by real-time RT-PCR (A), and immunoblot (B). (C, D) Podocytes were treated with 100 nmol/L Aldo for the indicated times. Nephrin mRNA and protein expression were detected by real time RT-PCR (C) and immunoblotting (D). (B, D) Left panel: representative immunoblots; right panel: densitometric analysis. Values represent mean ± SEM; n = 6. *P < 0.01 versus control by the analysis of variance test. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

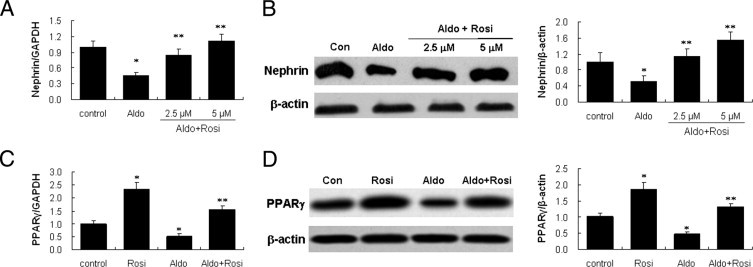

Rosiglitzone at 2.5 μmol/L or 5 μmol/L completely restored nephrin expression (Figure 2, A and B); an increased dose at 10 μmol/L induced apoptosis (data not shown). We also examined PPARγ expression in both Aldo-treated and rosiglitazone-pretreated cells. Aldo inhibited PPARγ expression, and rosiglitazone prevented PPARγ down-regulation by Aldo (Figure 2, C and D).

Figure 2.

Effect of rosiglitazone on nephrin and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ expression in podocytes. (A, B) Podocytes were pretreated with rosiglitazone (Rosi) (2.5, 5 μmol/L) for 30 minutes, followed by aldosterone (Aldo) (100 nmol/L) for 48 hours, and nephrin mRNA and protein were detected by real-time RT-PCR (A) and immunoblot (B). (C, D) Podocytes were pretreated with Rosi (5 μmol/L) for 30 minutes, followed by Aldo (100 nmol/L) for 48 hours, and PPARγ mRNA and protein were detected by real-time RT-PCR (C) and immunoblot (D). (B, D) Left panel: representative immunoblots; right panel: densitometric analysis. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 6. *P < 0.01 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus Aldo-treated group by analysis of variance.

Mitochondrial Originated ROS Mediates Aldo-Induced Podocyte Injury

Given the recent evidence for involvement of ROS in the podocyte injury,3,26,27 we first tested whether ROS mediate Aldo-induced down-regulation of nephrin. 2′,7′ dichlorfluorescein (DCF) fluorescence, an index of ROS production, was significantly increased after 60 minutes of Aldo treatment, and this increase was prevented by rosiglitazone treatment (Figure 3, A–C).

Figure 3.

Aldosterone (Aldo)-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and its origin in podocytes. A: Podocytes in chamber slides were pretreated with eplerenone (EPL) (10 μmol/L), rosiglitazone (Rosi) (5 μmol/L), or rotenone (ROT) (10 μmol/L) for 30 minutes, and were then exposed to Aldo (100 nmol/L) for 60 minutes in the presence of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) diacetate. B, C: Quantitative analysis of ROS. Podocytes in 6-well plates were treated as above-mentioned and florescence was quantified by fluorescence-assisted cell sorting (FACS). D: Effect of ROS on nephrin expression. Podocytes were pretreated with EPL (10 μmol/L), rosiglitazone (Rosi) (5 μmol/L), or ROT (10 μmol/L) for 30 minutes, and were then exposed to Aldo (100 nmol/L) for 48 hours. Nephrin mRNA was determined by real time RT-PCR. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < 0.01 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus Aldo-treated group by analysis of variance.

We previously reported that Aldo-induced ROS originated from mitochondria.6 To validate this phenomenon, we tested the effect of rotenone on Aldo-induced ROS production in podocytes. Indeed, the induction of ROS production in response to Aldo treatment was inhibited by rotenone (Figure 3, A–C). We next determined the effect of rotenone on nephrin expression. Rotenone almost completely restored nephrin expression (Figure 3D). These results suggested that mt-derived oxidative stress mediated Aldo-induced podocyte injury, and that the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone protected against podocyte injury by inhibiting mt ROS production.

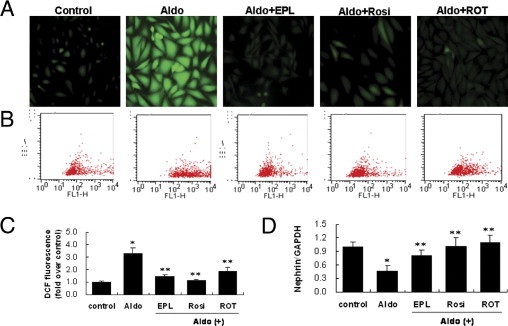

Aldo-Induced MtD in Podocytes via MR

MtD is characterized by concurrent high superoxide production and breakdown of membrane potential, and is often associated with disturbance of intracellular ATP synthesis and mtDNA damage.28 Based on the observation that Aldo-induced ROS originated from mt, we investigated if Aldo induced MtD. The mt ultrastructure morphology of Aldo-treated cells displayed mt vacuolization and decreased distribution in podocytes (Figure 4A). Aldo treatment resulted in a significant loss in MMP (Figure 4B), and a reduction in ATP content (Figure 4C). The copy number ratio of mtDNA to nuclear DNA (mtDNA/18S rRNA) was also sensitive to Aldo. After 12 hours of Aldo treatment, mtDNA/18S rRNA was significantly decreased compared to the control (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Effect of eplerenone (EPL) and rosiglitazone (Rosi) on aldosterone (Aldo)-induced mitochondrial damage in podocytes. The podocytes were treated with Aldo (100 μmol/L) for 12 hours in the presence or absence of EPL (10 μmol/L) or Rosi (5 μmol/L). Mitochondrial (mt) ultrastructure, mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), ATP content, and mtDNA copy number were determined (see Materials and Methods). A: Mt morphological changes. The mt superstructure was detected by transmission electron micrograph. Arrow indicates mt vacuolization (×30,000). B: MMP. C: ATP production. D: mtDNA copy number. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < 0.01 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus Aldo-treated group by analysis of variance.

To address the functional role of mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), we examined the effect of the MR antagonist eplerenone on Aldo-induced MtD. As shown in Figures 3 and 4, in the presence of eplerenone, MtD and podocyte damage were almost completely prevented as assessed by changes in ROS production, mt vacuolization, MMP, ATP content, and mtDNA copy number.

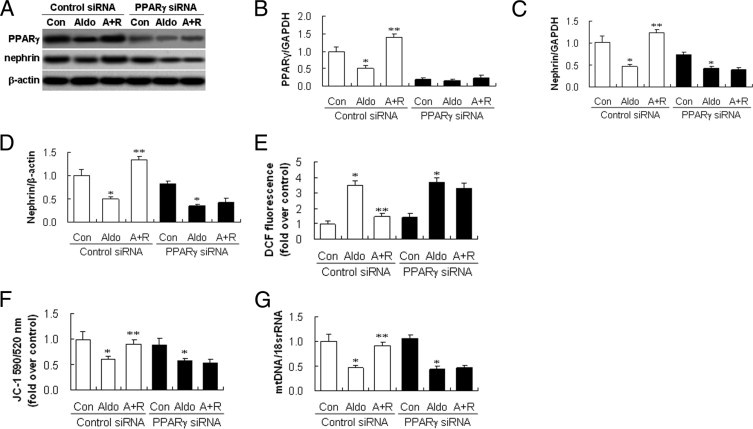

Effects of Rosiglitazone on Aldo-Induced MtD in Podocytes

Next, we examined the effect of rosiglitazone on Aldo-induced MtD. Aldo-induced mt vacuolization and decreased distribution were attenuated by rosiglitazone pretreatment (Figure 4E). Rosiglitazone almost completely restored MMP, ATP content, and mtDNA copy number (Figure 4, F–H). To confirm that rosiglitazone prevents podocyte injury and protects mitochondrial function via PPARγ, we evaluated the effect of PPARγ siRNA on nephrin expression, ROS production, MMP, and mtDNA copy number. Transfection of podocytes with PPARγ siRNA suppressed PPARγ proteins by >75%, whereas a control siRNA had no effect (Figure 5, A and B). Rosiglitazone was ineffective in restoring nephrin mRNA and protein expression in Aldo-stimulated podocytes transfected with PPARγ siRNA, whereas it remained effective in podocytes transfected with control siRNA (Figure 5, C and D). Furthermore, rosiglitazone failed to attenuate ROS significantly in cells transfected with specific PPARγ siRNA (Figure 5E). Parallel to the effect on ROS, PPARγ siRNA abrogated the action of rosiglitazone in attenuating the disruption of MMP and mtDNA replication (Figure 5, F and G). These results indicate that rosiglitazone protects podocytes and maintains mitochondrial function via PPARγ.

Figure 5.

Rosiglitazone protects podocyte and restores mitochondrial function in a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ dependent manner. Podocytes transfected with PPARγ or control small interference RNA (siRNA) were treated with rosiglitazone and subjected to aldosterone (Aldo). Nephrin mRNA and proteins, and PPARγ proteins, were analyzed by real time RT-PCR and immunoblotting, respectively. ROS production, mitochondrial membrane potential, and mitochondrial (mt)DNA copy number in podocytes were detected (see Materials and Methods). A: Representative blot of PPARγ and nephrin. B: Densitometric analysis of PPAR-γ protein. C: Nephrin mRNA analysis. D: Densitometric analysis of nephrin protein. E: Quantitative analysis of ROS. F: MMP. G: mtDNA copy number. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 6. *P < 0.01 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus Aldo-treated group by analysis of variance. A+R, infected with siRNA and treated with Rosi and Aldo; Con, only control siRNA or PPARγ siRNA; DCF, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

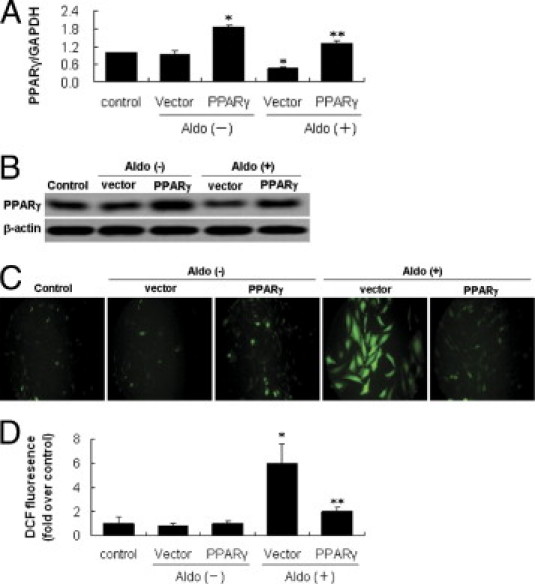

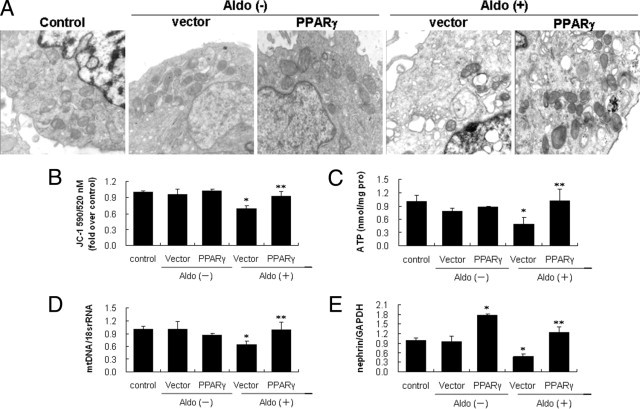

PPARγ Overexpression Inhibits Aldo-Induced MtD

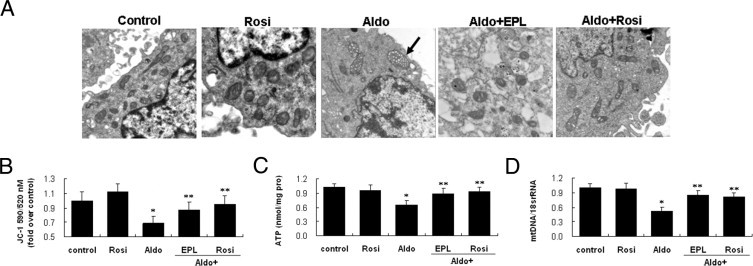

In light of the specificity issue that might be related with rosiglitazone, we examined the effect of PPARγ overexpression on Aldo-induced MtD. PPARγ expression as evaluated by real-time RT-PCR and immunoblotting was significantly increased in the cells transfected with the PPARγ cDNA as compared with the empty vector group and the same phenomenon was observed in the presence or absence of Aldo (Figure 6, A and B). ROS overproduction induced by Aldo was inhibited by PPARγ overexpression (Figure 6, C and D). PPARγ overexpression markedly attenuated Aldo-induced mt vacuolization and also decreases in mt density, resulting in a higher percentage of cells with normal MMP and ATP production, and mtDNA copy number (Figure 7, A–D). Moreover, PPARγ overexpression significantly restored the nephrin expression that was down-regulated by Aldo treatment (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

Effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ overexpression on aldosterone (Aldo)-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in podocytes. A, B: PPAR-γ expression in pcDNA3.1-PPAR-γ transfected podocytes. The podocytes were transfected with pcDNA3.1-PPAR-γ (PPAR-γ) or empty vector (vector), with untreated cells used as the control. A: Real-time RT-PCR analysis of PPAR-γ mRNA expression. B: Immunoblot of PPAR-γ protein expression. C: Podocytes in chamber slides were transfected with pcDNA3.1-PPAR-γ, and then exposed to Aldo (100 nmol/L) for 60 minutes in the presence of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate. D: Quantitative analysis of ROS. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < 0.01 versus control and empty vector; **P < 0.01 versus vector plus Aldo group by analysis of variance.

Figure 7.

Effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ overexpression on aldosterone (Aldo)-induced mitochondrial (mt) damage and podocyte injury. The podocytes were transfected with vector or pcDNA3.1-PPAR-γ and exposed to Aldo (100 nmol/L) for an additional 12 hours. Mt ultrastructure, mitochondrial membrane potential, ATP content, mtDNA copy number, and nephrin mRNA expression were determined (see Materials and Methods). A: Mt morphological changes (×30,000). B: Mitochondrial membrane potential. C: ATP production. D: mtDNA copy number. E: Nephrin mRNA expression. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < 0.01 versus control and empty vector; **P < 0.01 versus vector plus Aldo group by analysis of variance. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

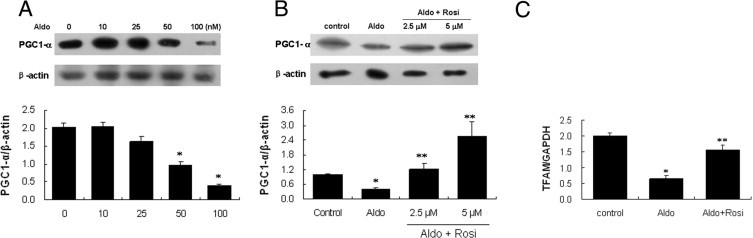

Effects of Rosiglitazone on PGC-1α and TFAM

PGC-1α is a key regulator of mt biogenesis and function through its interactions with the nuclear respiratory factor.29 Aldo induced a marked decrease in PGC-1α expression in a dose-dependent manner with an effect noticeable at 50 nmol/L and maximal at 100 nmol/L (Figure 8A). In contrast, rosiglitazone progressively and significantly increased PGC-1α expression, with a maximum effect at 5 μmol/L (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Effects of rosiglitazone (Rosi) on peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator (PGC)-1α, and PGC-1α-dependent mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) expression. A: Podocytes were treated with aldosterone (Aldo) as indicated for 24 hours, and PGC-1α expression was determined by immunoblotting. B: Podocytes were pretreated with Rosi (2.5, 5 μmol/L) for 30 minutes followed by aldosterone (Aldo) (100 nmol/L) for 24 hours, and PGC-1α expression was determined by immunoblotting. A, B: Upper panel: representative immunoblots; lower panel: densitometric analysis. C: Podocytes were treated with Aldo (100 μmol/L) for 12 hours in the presence or absence of Rosi (5 μmol/L). TFAM mRNA expression was detected by real time RT-PCR. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 6. *P < 0.01 versus control; **P < 0.01 versus Aldo-treated group by analysis of variance. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Mt transcription factor A (TFAM) is an essential factor for mtDNA transcription initiation, and is a packaging factor that stabilizes mtDNA. As shown in Figure 8C, TFAM mRNA was down-regulated by Aldo treatment and restored by rosiglitazone.

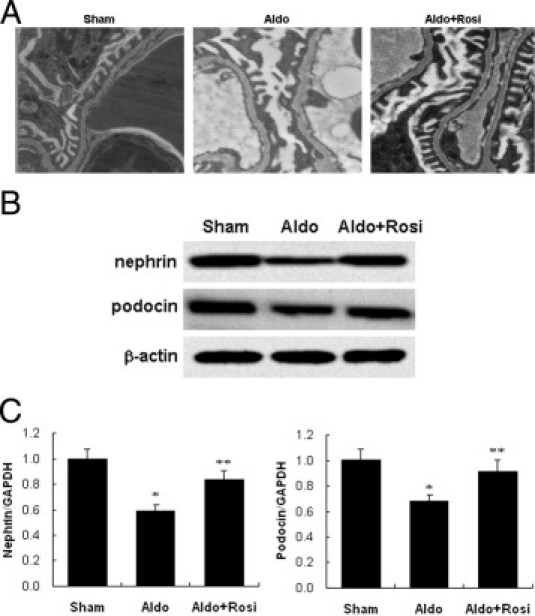

Effects of Rosiglitazone on Podocyte Injury in Aldo-Infused Mice

Kidney ultrastructure morphology of Aldo-infused mice showed foot-process effacement, which appeared as sheets covering the glomerular basement membrane, with disappearance of the slit diaphragm gap (Figure 9A). Nephrin and podocin expression were down-regulated in Aldo-infused mice (Figure 8, B and C) in which urinary protein excretion increased by 12-fold (Figure 10A). In contrast, rosiglitazone tretament produced a significant amelioration of kidney histopathology development (Figure 9C), podocyte injury (Figure 9, B and C), and urinary protein excretion in Aldo-infused animals (Figure 10A).

Figure 9.

Effects of rosiglitazone (Rosi) on podocyte injury in mice. A: Morphology changes of podocyte foot processes by electron microscopy (×12,000). B: Cortex nephrin and podocin protein expression by immunoblot. C: Cortex nephrin and podocin mRNA expression by real-time RT-PCR. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < 0.05 versus sham group; **P < 0.05 versus the aldosterone (Aldo)-treated group by analysis of variance. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Figure 10.

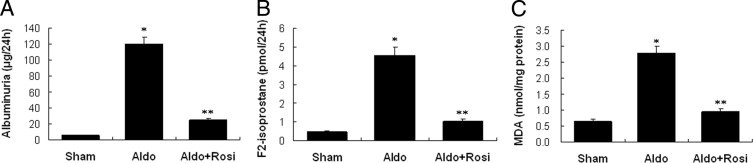

Effects of rosiglitazone (Rosi) on albuminuria, urinary F2-isoprostane excretion, and kidney malondialdehyde (MDA) content in mice. A: Albuminuria. B: Urinary F2-isoprostane. C: Kidney cortex MDA. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < 0.01 versus sham group; **P < 0.01 versus aldosterone (Aldo)-treated group by analysis of variance.

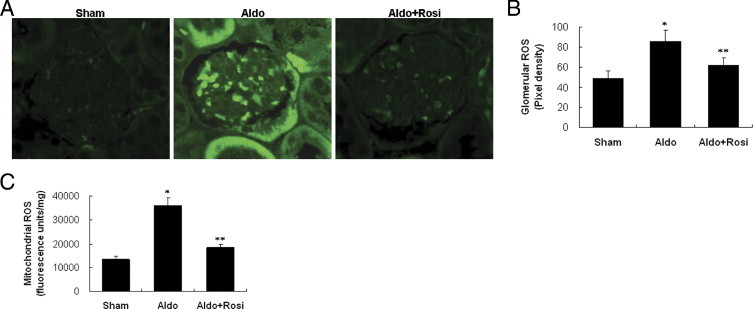

Increased Glomerular ROS Production in Aldo-Treated Mice and the Effects of Rosiglitazone

After 14 days of Aldo infusion, the urine levels of F2-isoprostane (a specific marker of renal oxidative stress)30 rose, which supports renal oxidative stress (Figure 10B).Glomeruli in Aldo-infused mice showed a significant increase in malondialdehyde (Figure 10C), a measure of glomerular lipid oxidation. Kidney sections from the Aldo-infused mice showed increased ROS generation in renal glomeruli and proximal tubular epithelial cells, compared to sham controls (Figure 11A). Glomerular ROS generation was decreased by rosiglitazone treatment (Figure 11, A and B). The increased glomerular ROS generation was from mt, because Aldo-infusion increased mt ROS production by 2.5-fold. Moreover, rosiglitazone reduced glomerular mt ROS levels by 87% (Figure 11C).

Figure 11.

Effect of rosiglitazone (Rosi) on kidney ROS production. A: Representative 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) staining of hydrogen peroxide in the kidney (×400). B: Quantification of the pixel density of DCF stainings in glomeruli. C: Kidney mitochondrial levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < 0.01 versus sham group; **P < 0.01 versus aldosterone (Aldo)-treated group by analysis of variance.

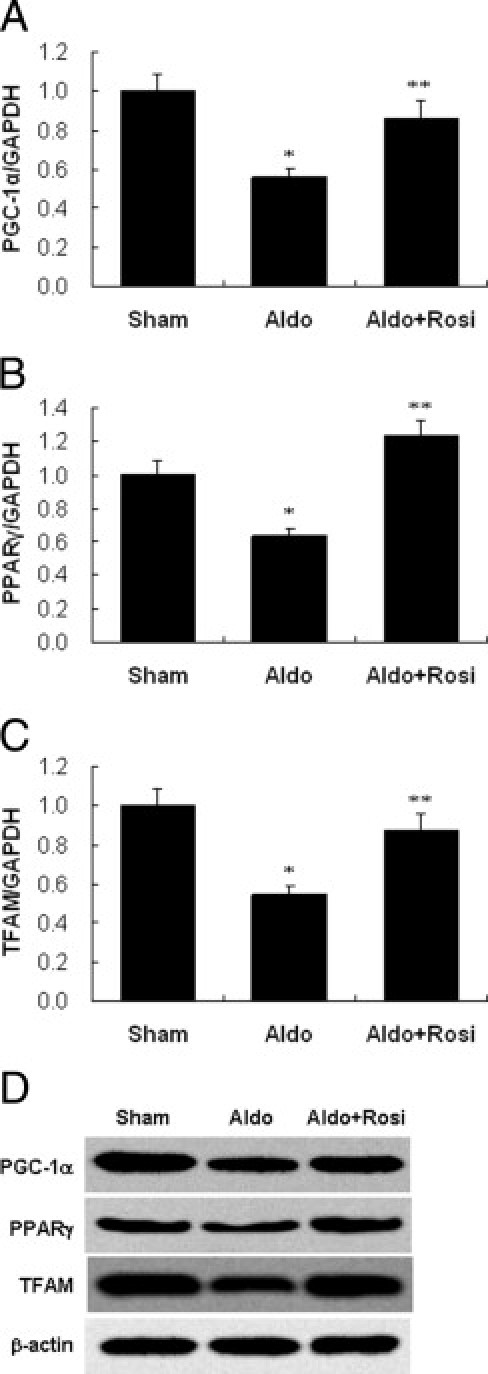

Effects of Rosiglitazone on Mitochondria and Renal PGC-1α, PPARγ, and TFAM Expression

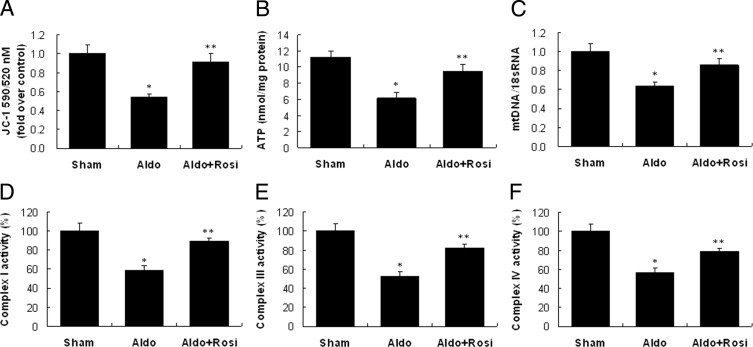

MMP was measured as a marker of mt function. MMP decreased 50% in mt isolated from Aldo-infused mice (Figure 12A). In accordance with the reduced MMP, the ATP content of glomeruli from Aldo-infused mice was significantly reduced (Figure 12B). In the isolated glomeruli, the mtDNA copy number was significantly decreased to 40% after Aldo infusion (Figure 12C).

Figure 12.

Effect of rosiglitazone (Rosi) on mitochondrial (mt) function in the kidney. A: Mitochondrial membrane potential. B: ATP content. C: mtDNA copy number. D: Mt complex I activity. E: Mt complex III activity. F: Mt complex I activity. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < 0.01 versus sham group; **P < 0.01 versus Aldo-treated group by analysis of variance.

The activity of respiratory chain enzyme complexes I, III, and IV was reduced by 40% to 50% in Aldo-infused mice (Figure 12, D–F). The enzymatic activity of complex II, encoded by nuclear DNA, was unaltered. MtD, as shown by down-regulation of MMP, mtDNA copy number, and mt enzymatic activity, occurred in glomeruli after Aldo infusion, and was signficantly attenuated by rosiglitazone (Figure 12).

As shown in Figure 13, PGC-1α, PPARγ, and TFAM mRNA, and protein levels were down-regulated after Aldo infusion compared to sham controls. Rosiglitazone stimulated PGC-1α, PPARγ, and TFAM mRNA, and protein expression in glomeruli.

Figure 13.

Effect of rosiglitazone (Rosi) on peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator (PGC)-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ, and mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) expression in the kidney. PGC-1α (A), PPAR-γ (B), and TFAM (C) mRNA expression was examined by real-time RT-PCR. D: Representative immunoblot of PGC-1α, PPAR-γ, and TFAM in the cortex. Data are mean ± SEM; n = 8. *P < 0.01 versus sham group; **P < 0.01 versus Aldo-treated group by analysis of variance. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

Discussion

It has been well demonstrated that podocyte injury underlies proteinuria and glomerulopathy induced by mineralocorticoid excess.9,31 Further evidence suggests a role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of podocyte injury in Aldo-infused rats.3 However, the source of Aldo-induced oxidative stress in podocytes is still poorly characterized. Mitochondria are important cellular organelles for the energy production pathway, oxidative phosphorylation that is associated with the generation of the by-product superoxide anion (O2.). Approximately 0.4% to 4% of the molecular oxygen (O2) consumed by the mitochondria is reduced by a single electron transfer from the initial steps of the electron transport chain to form O2.32–34 There is a growing appreciation of mitochondria respiratory chain as an important source of oxidative stress under states of aging, diabetes, and so forth.35–40 Our recent study suggests an important role of mitochondrial-derived ROS in Desoxycorticosterone Acetate (DOCA)-salt hypertension in mice (Zhang A, et al., unpublished data). Therefore, we were prompted to assess the role of mitochondrial-derived ROS in Aldo-induced podocyte injury. We chose the model of Aldo infusion with normal salt in the present study, because this model is not associated with a significant increase in blood pressure due to the escape mechanism (data not shown), thereby allowing assessment of the direct action of Aldo. We demonstrated that Aldo-infused C57BL/6J mice induced proteinuria and podocyte injury, accompanied by MtD, as assessed by the measurements of MMP, ATP levels, and mtDNA copy number, and the activity of complexes I, III, and IV. In vitro studies further provide compelling evidence that MtD is directly responsible for Aldo-induced ROS generation and podocyte damage. Moreover, we demonstrate that improvement of mt function underlies the anti-proteinuric effects of the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone.

Beside mt respiratory chain, NADPH oxidase is another important ROS generating system. In fact, evidence is available that podocyte injury is associated with increased NADPH oxidase activity in the kidney of Aldo-infused rats.3 However, the functional role of NADPH oxidase in this model is not tested. In contrast, we provide evidence that mt electron-transfer chain inhibitor rotenone was effective in inhibiting Aldo-induced ROS generation and podocyte injury in vitro. Future in vivo studies are needed to assess the relative importance of mt respiratory chain versus NADPH oxidase as a source of glomerular ROS production during mineralocorticoid excess.

Aldo-induced ROS originated from mt, and MMP was reduced in Aldo-stimulated podocytes, as well as in glomeruli from Aldo-infused mice. The functional relevance of these results was confirmed by reduced ATP levels. Mt morphology is important for normal mt function through maintenance of the metabolite and protein balance between internal compartments.41 Yu et al42 found that a dynamic change in mt morphology is an important contributor to ROS overproduction in high glucose. In Aldo-infused podocytes, most mt were vacuolated and condensed, consistent with the observed ROS production.

We demonstrated that Aldo treatment induced a 50% to 60% reduction of mtDNA copy number in cultured podocytes in vitro and in glomeruli in vivo. Consistent with decreased mtDNA number, the activities of complexes I, III, and IV were significantly lower in glomeruli from Aldo-infused mice than sham controls. This finding is of clinical relevance to human glomerular disease. For example, Solin et al43 reported that a reduction in mtDNA copy number in the kidney cortex accounts for MtD in Finnish type congenital nephrotic syndrome. Holthofer et al44 also reported down-regulation of the mitochondrially encoded respiratory chain complex in glomeruli isolated from the same patients. MtDNA is prone to oxidative stress and is more easily affected than nuclear DNA, because it lacks histone-like proteins and has a limited DNA repair system.11 Consequently, a decrease in mtDNA copy number might be a direct effect of ROS generation from Aldo treatment. TFAM directly binds mtDNA. PGC-1α is epistatic to TFAM, and both are recognized as key regulators of mtDNA biogenesis.25 In this study, expression of TFAM and PGC-1α was down-regulated in response to Aldo treatment and might be directly responsible for the reduced mtDNA number.

MR is suggested to mediate the pathogenic role of Aldo. We demonstrated that blockade of MR with eplerenone remarkably inhibited Aldo-induced MtD and prevented podocyte damage. The evidence obtained from our cell culture model suggests that MR is likely responsible for the pathogenic actions of Aldo in podocytes.

Another important finding is that improvement of MtD underlies the renoprotective effect of the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone in Aldo-infused mice. We found that rosiglitazone attenuated podocyte damage and proteinuria, accompanied by improvement of mt structure and function, as evidenced by the restoration of mt morphology, mtDNA copy number, MMP levels, and mt electron transport function. A PPARγ siRNA, which knocks down the constitutively expressed PPARγ by >75% abrogated the protective action of rosiglitazone on podocyte. The findings indicate that the effect of rosiglitazone is PPARγ-dependent. Interestingly, overexpression of PPARγ without concurrent rosiglitazone treatment elicited a protective effect in a manner resembling rosiglitazone in podocyte. Besides Aldo-induced kidney injury, PPARγ agonists exhibited anti-proteinuric and renoprotective effects in a wide variety of acute and chronic kidney injury models, such as diabetic nephropathy.

In addition, we demonstrated that rosiglitazone increased PGC-1α and TFAM expression in vivo and in vitro. PGC-1α, a transcriptional co-activator of PPARγ and other nuclear hormone receptors, is a major regulator of oxidative metabolism and mitochondrial function. PGC-1α binds to and co-activates the transcriptional function of the nuclear respiratory factor-1 on the promoter for TFAM, a direct regulator of mtDNA replication.45 The overexpression of PGC-1α results in a robust increase in mitochondrial number, cellular respiration, and intracellular ATP concentrations in a variety of cell types, whereas the repression of PGC-1α expression by a mutant histone deacetylase 5 results in loss of and morphological changes to mitochondria and in down-regulation of mitochondrial enzymes.45 It has been reported that PPARγ interacts with PGC-1α in a ligand-independent manner,46 suggesting that rosiglitazone augments expression of both arms to amplification of mt expression: PPARγ and PGC-1α. More studies in the future will be needed to investigate the effect of PGC-1α on the Aldo-induced podocyte MtD and cell injury.

In summary, we present new evidence that MtD contributes to Aldo-induced oxidative stress and subsequent podocyte injury, and that the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone protects against Aldo-induced podocyte injury via restoration of mt function. These findings provide new insights into the pathogenic process of Aldo-induced podocyte injury and also identify a new therapeutic target of PPARγ agonists for glomerular diseases.

Footnotes

Supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30872803 to A.Z) and (30971376 to G.D.); the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK2009046 to A.Z.); and the National Institutes of Health (HL079453 to T.Y.), and a VA Merit Review to T.Y.

Contributor Information

Songming Huang, Email: smhuang@njmu.edu.cn.

Aihua Zhang, Email: zhaihua@njmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Greene E.L., Kren S., Hostetter T.H. Role of aldosterone in the remnant kidney model in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1063–1068. doi: 10.1172/JCI118867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein M. Aldosterone as a mediator of progressive renal disease: pathogenetic and clinical implications. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:677–688. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(01)80115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shibata S., Nagase M., Yoshida S., Kawachi H., Fujita T. Podocyte as the target for aldosterone: roles of oxidative stress and Sgk1. Hypertension. 2007;49:355–364. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000255636.11931.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiyomoto H., Rafiq K., Mostofa M., Nishiyama A. Possible underlying mechanisms responsible for aldosterone and mineralocorticoid receptor-dependent renal injury. J Pharmacol Sci. 2008;108:399–405. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08r02cr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein M. Aldosterone blockade: an emerging strategy for abrogating progressive renal disease. Am J Med. 2006;119:912–919. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang A., Jia Z., Guo X., Yang T. Aldosterone induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition via ROS of mitochondrial origin. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F723–F731. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00480.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sato A., Hayashi K., Saruta T. Antiproteinuric effects of mineralocorticoid receptor blockade in patients with chronic renal disease. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ambroisine M.L., Milliez P., Nehme J., Pasquier A.L., De Angelis N., Mansier P., Swynghedauw B., Delcayre C. Aldosterone and anti-aldosterone effects in cardiovascular diseases and diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Metab. 2004;30:311–318. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nagase M., Shibata S., Yoshida S., Nagase T., Gotoda T., Fujita T. Podocyte injury underlies the glomerulopathy of Dahl salt-hypertensive rats and is reversed by aldosterone blocker. Hypertension. 2006;47:1084–1093. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000222003.28517.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagata M., Yamaguchi Y., Ito K. Loss of mitotic activity and the expression of vimentin in glomerular epithelial cells of developing human kidneys. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1993;187:275–279. doi: 10.1007/BF00195765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagiwara M., Yamagata K., Capaldi R.A., Koyama A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis of puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1146–1152. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kriz W., Lemley K.V. The role of the podocyte in glomerulosclerosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1999;8:489–497. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199907000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iglesias P., Diez J.J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonists in renal disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:613–621. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang H.C., Ma L.J., Ma J., Fogo A.B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonist is protective in podocyte injury-associated sclerosis. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1756–1764. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson-Fritch L., Burkart A., Bell G., Mendelson K., Leszyk J., Nicoloro S., Czech M., Corvera S. Mitochondrial biogenesis and remodeling during adipogenesis and in response to the insulin sensitizer rosiglitazone. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1085–1094. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.1085-1094.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson-Fritch L., Nicoloro S., Chouinard M., Lazar M.A., Chui P.C., Leszyk J., Straubhaar J., Czech M.P., Corvera S. Mitochondrial remodeling in adipose tissue associated with obesity and treatment with rosiglitazone. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1281–1289. doi: 10.1172/JCI21752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schutz B., Reimann J., Dumitrescu-Ozimek L., Kappes-Horn K., Landreth G.E., Schurmann B., Zimmer A., Heneka M.T. The oral antidiabetic pioglitazone protects from neurodegeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-like symptoms in superoxide dismutase-G93A transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7805–7812. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2038-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quintanilla R.A., Jin Y.N., Fuenzalida K., Bronfman M., Johnson G.V. Rosiglitazone treatment prevents mitochondrial dysfunction in mutant huntingtin-expressing cells: possible role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARgamma) in the pathogenesis of Huntington disease. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:25628–25637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804291200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mundel P., Reiser J., Kriz W. Induction of differentiation in cultured rat and human podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:697–705. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V85697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang J.H., Lu L., Lu H., Chen X., Jiang S., Chen Y.H. Identification of the HIV-1 gp41 core-binding motif in the scaffolding domain of caveolin-1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6143–6152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katsuya K., Yaoita E., Yoshida Y., Yamamoto Y., Yamamoto T. An improved method for primary culture of rat podocytes. Kidney Int. 2006;69:2101–2106. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang S., Zhang A., Ding G., Chen R. Aldosterone-induced mesangial cell proliferation is mediated by EGF receptor transactivation. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F1323–F1333. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90428.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deegens J.K., Dijkman H.B., Borm G.F., Steenbergen E.J., van den Berg J.G., Weening J.J., Wetzels J.F. Podocyte foot process effacement as a diagnostic tool in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1568–1576. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J.S., Lin T.N., Wu K.K. Rosiglitazone and PPAR-gamma overexpression protect mitochondrial membrane potential and prevent apoptosis by upregulating anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins. J Cell Physiol. 2009;220:58–71. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeuchi M., Matsusaka H., Kang D., Matsushima S., Ide T., Kubota T., Fujiwara T., Hamasaki N., Takeshita A., Sunagawa K., Tsutsui H. Overexpression of mitochondrial transcription factor a ameliorates mitochondrial deficiencies and cardiac failure after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2005;112:683–690. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.524835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whaley-Connell A., DeMarco V.G., Lastra G., Manrique C., Nistala R., Cooper S.A., Westerly B., Hayden M.R., Wiedmeyer C., Wei Y., Sowers J.R. Insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and podocyte injury: role of rosuvastatin modulation of filtration barrier injury. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28:67–75. doi: 10.1159/000109394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whaley-Connell A.T., Chowdhury N.A., Hayden M.R., Stump C.S., Habibi J., Wiedmeyer C.E., Gallagher P.E., Tallant E.A., Cooper S.A., Link C.D., Ferrario C., Sowers J.R. Oxidative stress and glomerular filtration barrier injury: role of the renin-angiotensin system in the Ren2 transgenic rat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F1308–F1314. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00167.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuenzalida K., Quintanilla R., Ramos P., Piderit D., Fuentealba R.A., Martinez G., Inestrosa N.C., Bronfman M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma up-regulates the Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic protein in neurons and induces mitochondrial stabilization and protection against oxidative stress and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:37006–37015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700447200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Z., Puigserver P., Andersson U., Zhang C., Adelmant G., Mootha V., Troy A., Cinti S., Lowell B., Scarpulla R.C., Spiegelman B.M. Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell. 1999;98:115–124. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Haan J.B., Stefanovic N., Nikolic-Paterson D., Scurr L.L., Croft K.D., Mori T.A., Hertzog P., Kola I., Atkins R.C., Tesch G.H. Kidney expression of glutathione peroxidase-1 is not protective against streptozotocin-induced diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F544–F551. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00088.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagase M., Yoshida S., Shibata S., Nagase T., Gotoda T., Ando K., Fujita T. Enhanced aldosterone signaling in the early nephropathy of rats with metabolic syndrome: possible contribution of fat-derived factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3438–3446. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006080944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chance B., Sies H., Boveris A. Hydroperoxide metabolism in mammalian organs. Physiol Rev. 1979;59:527–605. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandy B., Davison A.J. Mitochondrial mutations may increase oxidative stress: implications for carcinogenesis and aging? Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;8:523–539. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turrens J.F., Alexandre A., Lehninger A.L. Ubisemiquinone is the electron donor for superoxide formation by complex III of heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1985;237:408–414. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90293-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Semenkovich C.F. Insulin resistance and atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1813–1822. doi: 10.1172/JCI29024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levine R.L., Garland D., Oliver C.N., Amici A., Climent I., Lenz A.G., Ahn B.W., Shaltiel S., Stadtman E.R. Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:464–478. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86141-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muscari C., Guarnieri C., Biagetti L., Finelli C., Caldarera C.M. Influence of age on oxidative damage in mitochondria of ischemic and reperfused rat hearts. Cardioscience. 1990;1:275–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birch-Machin M.A. The role of mitochondria in ageing and carcinogenesis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:548–552. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Passos J.F., von Zglinicki T., Saretzki G. Mitochondrial dysfunction and cell senescence: cause or consequence? Rejuvenation Res. 2006;9:64–68. doi: 10.1089/rej.2006.9.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pamplona R., Barja G. Mitochondrial oxidative stress, aging and caloric restriction: the protein and methionine connection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:496–508. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mannella C.A. Structure and dynamics of the mitochondrial inner membrane cristae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:542–548. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu T., Robotham J.L., Yoon Y. Increased production of reactive oxygen species in hyperglycemic conditions requires dynamic change of mitochondrial morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2653–2658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511154103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Solin M.L., Pitkanen S., Taanman J.W., Holthofer H. Mitochondrial dysfunction in congenital nephrotic syndrome. Lab Invest. 2000;80:1227–1232. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holthofer H., Kretzler M., Haltia A., Solin M.L., Taanman J.W., Schagger H., Kriz W., Kerjaschki D., Schlondorff D. Altered gene expression and functions of mitochondria in human nephrotic syndrome. FASEB J. 1999;13:523–532. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.13.3.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lin J.D. Minireview: the PGC-1 coactivator networks: chromatin-remodeling and mitochondrial energy metabolism. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:2–10. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puigserver P., Wu Z., Park C.W., Graves R., Wright M., Spiegelman B.M. A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell. 1998;92:829–839. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81410-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]