Abstract

Phosphorylation of histone H2AX is an early response to DNA damage in eukaryotes. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, DNA damage or replication fork stalling results in histone H2A phosphorylation to yield γ-H2A (yeast γ-H2AX) in a Mec1 (ATR)- and Tel1 (ATM)- dependent manner. Here, we describe the genome-wide location analysis of γ-H2A as a strategy to identify loci prone to engage the Mec1 and Tel1 pathways. Remarkably, γ-H2A enrichment overlaps with loci prone to replication fork stalling and is caused by the action of Mec1 and Tel1, indicating that these loci are prone to breakage. Moreover, about half the sites enriched for γ-H2A map to repressed protein-coding genes, and histone deacetylases are necessary for formation of γ-H2A at these loci. Finally, our work indicates that high resolution mapping of γ-H2AX is a fruitful route to map fragile sites in eukaryotic genomes.

Introduction

DNA replication poses a major challenge to genome integrity1. Chromosomal fragile sites in the human genome are associated with defects in DNA replication progression and can lead to genome rearreangements2. Replisomes encounter a number of obstacles that must be overcome in order to complete DNA replication in a timely yet accurate manner. Inadequate nucleotide or histone supplies, DNA damage, protein-DNA complexes, gene transcription, chromatin organization and topological strain can all potentially block replication fork progression1.

In budding yeast, up to 1,400 sites have been proposed as potential impediments to replication forks. These sites include tRNA genes, Ty long-terminal repeats (LTRs), centromeres, DNA replication origins, the HMR and HML heterochromatic loci and the repeated rDNA units1,3–6. This list is an extrapolation based on the characterization of a few sites, rather than the result of high-resolution mapping of replication fork pausing. Other classes of replisome progression (or stability) obstacles have been identified7,8 indicating that the list described above might not be exhaustive. Importantly, these natural replication fork barriers have been linked to genome rearrangements, suggesting that some paused forks collapse or are processed at these sites3,9–12.

Generally, unscheduled replisome stalling elicits the activation of protein kinases of the PI(3) kinase-like kinase (PIKK) family, particularly the Mec1/ATR ortholog13–17. Activation of Mec1/ATR signaling stabilizes replication forks to prevent their collapse18,19 although the critical Mec1/ATR targets that promote fork stability remain unknown. Nevertheless, several phosphorylation events have been characterized in response to replication fork blocks. In particular, phosphorylation of histone H2AX is a near-universal feature of the eukaryotic response to genotoxic stress20–23. This phosphorylation event, yielding γ-H2AX (γ-H2A in Saccharomyces cerevisiae), can occur as a consequence of DNA replication fork stalling in an ATR/Mec1-dependent manner24,25. The link between γ-H2AX and replication fork stability is better established in S. cerevisiae where abrogation of γ-H2A by mutation of the HTA genes produces sensitivity to camptothecin, a topoisomerase I inhibitor that provokes replication-associated DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs)26. The same hta mutants are only mildly sensitive to other genotoxins, indicating that γ-H2A is important for the response to replication-associated DSBs.

In this study, we hypothesized that mapping γ-H2A in cycling cells might reveal fragile genomic loci. We employed a genome-wide location assay (chromatin immunoprecipitation on tiled microarray, or ChIP-chip) to map γ-H2A-rich loci (referred to herein as γ-sites). Our data shows that γ-sites are distributed non-randomly and are concentrated at telomeres, the rDNA locus, DNA replication origins, LTRs, tRNA genes and, surprisingly, actively repressed protein-coding genes. Using a combination of genetic studies and carbon source manipulation, we found that the chromatin structure promoted by histone deacetylation can lead to PIKK activation. We conclude that mapping sites of γ-H2AX enrichment will be a fruitful route to map at-risk genomic elements in eukaryotes.

RESULTS

Genome-wide location analysis of γ-H2A

To identify loci enriched in γ-H2A, we carried out ChIP with a phosphospecific antibody that recognizes yeast γ-H2A26 and hybridized the associated DNA to high-density genomic tiling arrays. We typically performed competitive hybridization of DNA precipitated from HTA1 HTA2 cells with DNA precipitated from the γ-H2A-deficient hta1-S129A hta2-S129A cells (referred to hereafter as h2a-S129A). We also tested other experimental designs controlling for nucleosome density that yielded similar results (Supplementary Fig. 1a). All experiments (listed in Supplementary Table 1) were done at least in duplicate and combined using a weighted average method27. The combined datasets are available in Supplementary File 1.

We first examined γ-H2A enrichment in asynchronously dividing cell cultures (Fig. 1a). Statistical analysis of the enrichment profile identified 697 unambiguous loci enriched in γ-H2A using the criterion of a peak with a p value <0.1 (Supplementary File 1). We refer to these loci asγ-sites. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses revealed no obvious cell cycle profile differences between wild-type and h2a-S129A cultures, thus excluding the possibility that differences in γ-H2A enrichment are simply due to differences in the cell cycle profiles (Supplementary Fig. 1b).

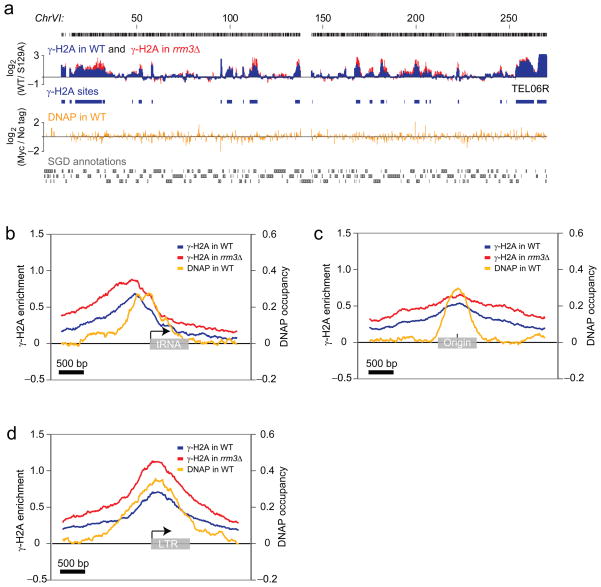

Figure 1.

Genome-wide location analysis of γ-H2A. (a) Genome browser capture of ChrVI. The log2γ-H2A/γ-H2A h2a-S129A enrichment ratio is shown for wild-type (WT; blue) and rrm3Δ (red) cells, along with the γ-H2A sites identified in the WT strain (blue boxes). The log2 DNAP-myc/untagged occupancy ratio is also shown (gold). The probes are shown as black bars and the Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) annotations are shown in grey. Chromosomal positions are indicated in kilobases. (b-d) Natural replication fork barriers promote γ-H2A formation. The average γ-H2A enrichment ratio for WT (blue) and rrm3Δ (red) cells, as well as the DNAP occupancy ratio (gold), are mapped on the complete non-mitochondrial sets of tRNA genes (b), DNA replication origins (c) and LTRs (d).

Statistically significant γ-sites vary in length but average 1255 bp. The average γ-site is therefore considerably shorter than 50 kb, the size of the γ-H2A domain caused by an unrepairable DSB delivered by the HO endonuclease28. Moreover, the shape of the γ-sites in our location analyses is strikingly different from the bimodal distribution of γ-H2A surrounding HO-induced DSBs28. The enrichments we observed generally displayed a single maximum intensity peak (see e.g. Fig. 1a). These differences suggest that the events monitored by γ-H2A ChIP in cycling cells are likely not irreparable DSBs.

In addition to mapping γ-sites in asynchronously dividing cells, we also analyzed cells synchronized in G1 by α-factor and cells synchronized at mid-S phase, obtained by releasing cells from a G1 block. The γ-H2A accumulation profiles in G1 and mid-S cells were highly similar to those obtained in asynchronous cultures (Supplementary Fig. 2). Since the γ-H2A profiles appeared highly similar whether cultures were synchronized or not, we pursued our analyses with datasets obtained from asynchronous cultures.

Visual and computational analysis of γ-sites identify 7 classes of genomic loci clearly enriched with γ-H2A in cycling cells: (i) telomeric regions, (ii) DNA replication origins, (iii) tRNA genes, (iv) LTRs, (v) the rDNA locus, (vi) the silent mating type cassettes HMR and HML, and (vii) a group of protein-coding genes (Supplementary Table 2). Apart from protein-coding genes, all of the above loci are known to impede replisome progression, strongly suggesting that γ-H2A detected in cycling cells is caused by replication fork pausing or collapse. Interestingly, we also observed γ-H2A enrichment at centromeres, another obstacle for replisomes, but the low number of centromeres in the yeast genome precluded this class of γ-site from being identified as statistically significant at the 0.1 p value.

Telomeres show striking γ-H2A enrichment at every chromosome end despite the paucity of probes covering the repetitive telomeric and subtelomeric regions. γ-H2A accumulation at telomeres, which was also observed in another study29, was also detected by ChIP followed by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR; Supplementary Fig. 3a). There is a strong correlation between the γ-H2A signal intensity and the proximity to the chromosome end (Supplementary Fig. 3b) whether or not the chromosome end contains a subtelomeric Y′ element (e.g. see TEL06R, which does not contain a Y′ element; Fig. 1a). This result indicates that Y′ subtelomeric elements are not responsible for the observed γ-H2A signal, suggesting that it originates either from the X element (common to all chromosome ends) or the TG repeats themselves. However, the significance of this telomeric enrichment is still unknown as h2a-S129A cells do not display any striking telomeric phenotype in all assays we tested so far (telomere length, telomeric silencing, senescence assays, telomere capping and chromosome healing, data not shown).

Visual inspection of the γ-H2A enrichment profiles identifies strong signals on ChrXII, at a region encompassing the rDNA locus (Supplementary Fig. 3c) and on ChrIII, which harbors the MAT locus and the silent mating type cassettes HMR and HML (Supplementary Fig. 3d,e). Observing γ-H2A enrichment at rDNA is not surprising since this locus experiences DNA strand breaks and recombination resulting from collisions between DNA replication forks and RNA polymerase I or via abortive decatenation reactions1. The HMR and HML loci are also known to impede replisomes, which might cause the observed signal30. However, these results are somewhat at odds with a recent report indicating that these heterochromatic regions are refractory to DSB-induced γ-H2A accumulation29, although we note that high levels of γ-H2A before DSB induction might have skewed the enrichment ratios calculated by Kim et al29.

γ-H2A accumulation correlates with replication fork blockage

Next, we mapped the γ-H2A enrichment ratios on all tRNA genes, DNA replication origins and LTR elements to identify sub-regions that might be responsible for the γ-H2A signal (Fig. 1b-d, blue traces). The γ-H2A enrichment profiles at tRNA genes are strikingly asymmetrical (Fig. 1b), peaking just before the RNA polymerase III transcription initiation site, and followed by a sharp fall in signal intensity. This enrichment is independent of any other nearby γ-H2A-enriched genomic loci (Supplementary Fig. 4). This asymmetry is consistent with tRNA genes being polar replication fork barriers5 where the obstacle to replisomes is the initiation complex rather than transcription itself3. TFIIIB binds the region immediately upstream of the tRNA gene transcription site, suggesting that DNA-bound TFIIIB elicits the γ-H2A signal observed at tRNA genes. In contrast, the averaged γ-H2A enrichment ratios at DNA replication origins (defined as peaks of Mcm7 and Mcm4 occupancy by ChIP-chip, see Methods) are largely symmetrical, peaking at the center of the origin where the pre-replication complex assembles. Likewise, the averaged γ-H2A enrichment ratios at LTRs are symmetrical, peaking at the 5′ end of the LTR.

Next we sought to map replication fork pausing at tRNA genes, DNA replication origins and LTRs in order to establish if the replisome accumulates or pauses at sites of γ-H2A enrichment. We therefore performed ChIP-chip analysis of myc-tagged Pol2, the catalytic subunit of DNA polymerase ε (DNAP). At first glance, we observed little similarity between DNAP and γ-H2A accumulation (Fig. 1a). However, averaging the DNAP signal at γ-sites revealed a striking accumulation of the replisome at these loci (Fig. 1b-d; gold traces). Since replication fork stalling or pausing can be defined by the accumulation of DNAP, these results suggest that the γ-sites are the consequence of impeded replisome progression.

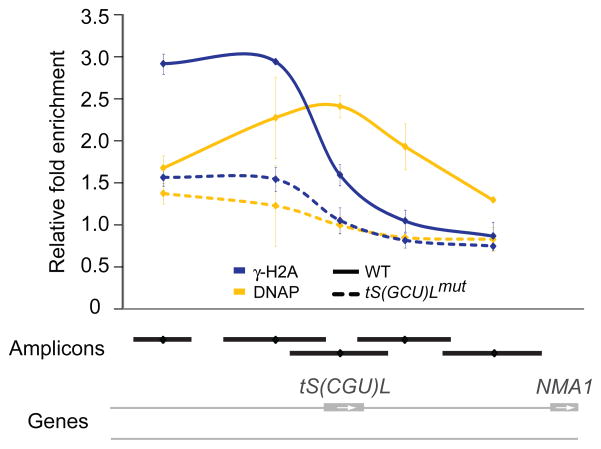

To directly test this possibility, we used the fact that mutation of the TFIIIB-binding site on tRNA genes abolishes the impediment to replication fork progression and greatly reduces replication fork stalling3. We therefore compared γ-H2A and DNAP enrichment by ChIP-qPCR at a tRNA gene (tS(GCU)L) that was either wild-type or contained a mutation in its TFIIIB-binding site (tS(GCU)Lmut). As expected, deletion of the TFIIIB-binding site abolished DNAP enrichment at this tRNA gene, indicating that replication forks no longer stall at the mutated tRNA gene (Fig. 2; gold curves). Satisfyingly, we observed that the γ-H2A signal was also abrogated at tS(GCU)Lmut (Fig. 2; blue curves). We therefore conclude that γ-H2A accumulates following unscheduled replication pausing, stalling or collapse.

Figure 2.

Mutation of the TFIIIB-binding site of a tRNA gene abolishes DNA polymerase and γ-H2A enrichment. Data is represented as the average relative fold enrichment and standard deviation of two experiments obtained by qPCR for DNAP (gold) and γ-H2A (blue) from WT (solid curves) and tS(GCU)Lmut (dashed curves) strains. The amplicons are represented as black lines and the SGD annotations are shown in grey.

γ-H2A accumulation is dependent on both Mec1 and Tel1

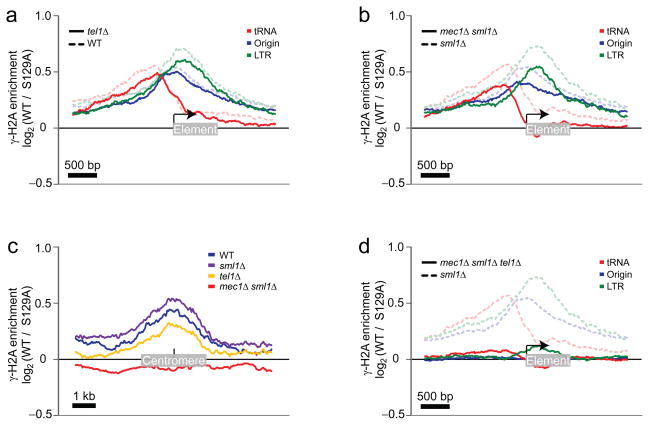

In response to replisome pausing or stalling, H2A is solely phosphorylated by Mec124 whereas Tel1 contributes to γ-H2A formation, redundantly with Mec1, only when DSBs are present21. These properties allowed us to determine whether γ-sites resulted from replication fork stalling, or whether DSBs also contributed to their formation. We therefore performed γ-H2A ChIP-chip in sml1Δ, mec1Δ sml1Δ, tel1Δ and mec1Δ sml1Δ tel1Δ cells. SML1 was deleted to circumvent the lethality of the MEC1 deletion and therefore sml1Δ acted as a control for strains with the MEC1 deletion. Not surprisingly, comparison of the total signal intensity ratios in the wild-type and sml1Δ strain revealed a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.82 (Supplementary Table 3) and no major differences in the profiles, indicating that sml1Δ did not affect H2A phosphorylation. Likewise, deletion of TEL1 or MEC1 did not have a major impact on the γ-H2A signals, with Pearson correlations of 0.82 and 0.85 when compared to their respective controls (Fig. 3a,b and Supplementary Table 3). However, deletion of either kinase led to a small decrease in the averaged signal intensities at tRNA genes, DNA replication origins and LTRs, indicating that both kinases contribute independently to γ-H2A accumulation at these sites (Fig. 3a,b). Upon closer inspection of the γ-sites in the mec1Δ sml1Δ strain, we observed that sites overlapping with most centromeres were strikingly absent in that strain (Fig. 3c). Moreover, the centromere-associated γ-H2A signal was also absent in G1 phase cells, indicating that these are labile γ-sites (Supplementary Fig. 2c). These results suggest that pericentromeric H2A phosphorylation primarily occurs following replication fork pausing.

Figure 3.

Mapping of the γ-H2A enrichment in cells harboring different combinations of TEL1, MEC1 and SML1 deletions on natural replication fork barriers. (a) Enrichment of γ-H2A from WT cells (blue curves from Figure 1b-d) are grouped on the same graph (tRNA genes in red, DNA replication origins in blue, and LTRs in green) and presented in dashed transparent curves while the γ-H2A enrichment detected in the tel1Δ cells is shown in solid curves. (b) As in a except that solid curves were obtained from mec1Δ sml1Δ cells while dashed curves represent sml1Δ control cells. (c) The γ-H2A enrichment was mapped in the middle of the 16 centromeres in WT (blue), sml1Δ (purple), tel1Δ (gold) and mec1Δ sml1Δ (red) cells. (d) As in b except that solid curves were obtained from the mec1Δ sml1Δ tel1Δ cells.

When the tel1Δ and mec1Δ mutations were combined together (in the sml1Δ background), all γ-sites were lost, leading to a Pearson correlation of 0.16 when compared to the sml1Δ control strain (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Table 3). Together, these results indicate that in a cell population, γ-sites are caused by a combination of replication fork stalling and collapse, consistent with the idea that the great majority of the γ-sites mapped represent fragile sites.

RRM3 regulates γ-sites

The Rrm3 helicase travels with the replication fork to facilitate fork progression through non-histone protein-DNA complexes3,31,32. RRM3 deletion increases the probability of replication fork stalling at ~1,400 potential sites in the genome3,31,32 that overlap remarkably with the γ-sites mapped in this study. We therefore mapped γ-H2A in rrm3Δ cells. The γ-H2A profile of rrm3Δ cells is qualitatively similar to that of wild-type (Fig. 1a, red) although in some regions, Rrm3 clearly dampens the γ-H2A signal. Figure 1b-d shows the profile of the averaged γ-H2A enrichment ratios at tRNA genes, DNA replication origins and LTRs in rrm3Δ cells overlaid against those obtained from wild-type cells. At these loci, the γ-H2A signal is on average more pronounced in the rrm3Δ strain than in wild-type, thus establishing a positive correlation between the extent of replication fork pausing and H2A phosphorylation at these sites4. This result strengthens the possibility that the γ-H2A enrichment is caused by replisome stalling and collapse.

Regulation of genome stability by γ-H2A

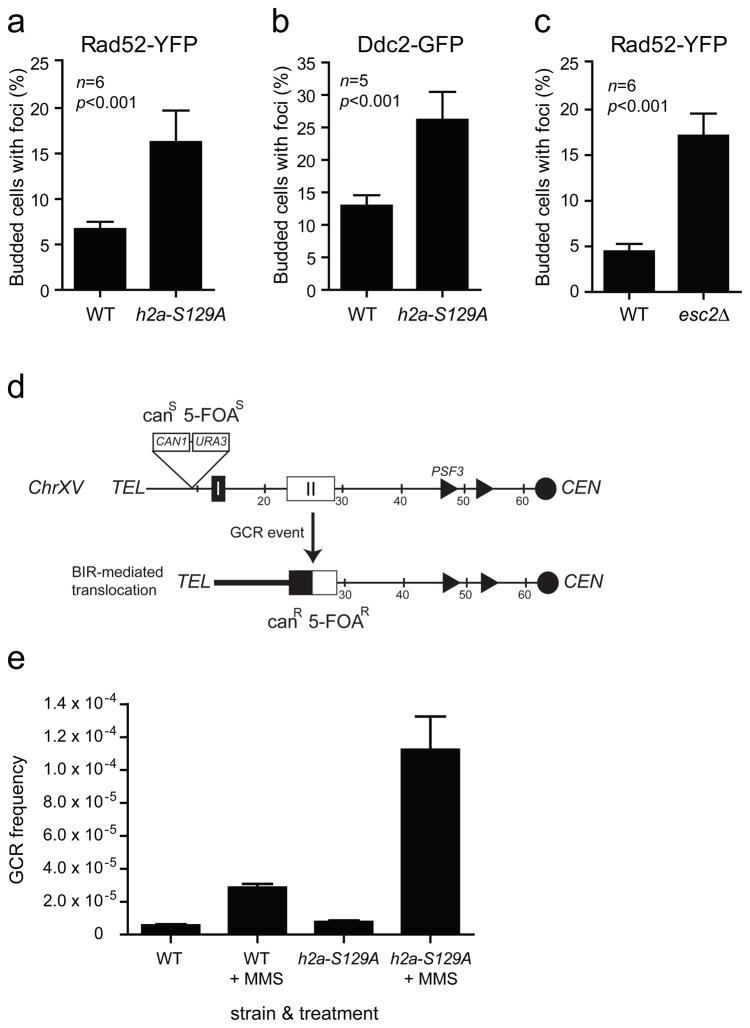

The majority of γ-sites mapped in this study are candidate fragile sites. Indeed, Ty retrotransposons, tRNA genes, replication origins and telomeres can promote genetic recombination or chromosome breakage10,12,33. To examine the relationship between γ-H2A and chromosome fragility in budding yeast, we investigated the relocation of Ddc2-GFP (green fluorescent protein) and Rad52-YFP (yellow fluorescent protein) into subnuclear foci34,35 in wild-type and h2a-S129A strains to assess whether γ-H2A prevents chromosome breakage. Mutation of H2A Ser129 elevated significantly the number of cells with Ddc2 or Rad52 foci (Fig. 4a,b). The increase in Rad52-YFP foci seen in h2a-S129A cells is comparable to that seen in esc2Δ cells (Fig. 4c) which have a moderate increase in genome instability36. Esc2 has recently been shown to contribute to genome integrity via the management of replication forks37,38. Since spontaneous Rad52 foci most likely arise following replication fork collapse35, these results suggest that γ-H2A not only marks sites of replication fork pausing but also plays a role in promoting replication fork integrity.

Figure 4.

Mutation of the H2A Ser129 residue increases the frequency of gross chromosomal rearrangements. (a-b) The h2a-S129A mutation results in an accumulation of Rad52-YFP (a) and Ddc2-GFP (b) foci. (c) Rad52-YFP foci accumulate in esc2Δ cells. Data is represented as the average and standard deviation of 6 (a,b) or 5 (c) experiments. Statistical significance (p value) was obtained with an unpaired t test. (d) The ChrXV-L GCR reporter chromosome. The assay monitors the loss of CAN1 and URA3 genes inserted ~10 kb from the telomere of ChrXV-L. This chromosome arm contains two regions of homology (HRI centered on the PAU20 gene, and HRII centered on the HXT11 gene) located 12 kb and 25 kb from the telomere that share a high degree of sequence identity with 21 regions in the genome40. Consequently, DNA lesions formed at loci telomeric to HRI or HRII are predominantly repaired by BIR, thereby converting a canavanine- and 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA)-sensitive strain (canS FOAS) into a canavanine and 5-FOA-resistant strain (canR 5-FOAR). (e) The h2a-S129A mutation results in an increased frequency of drug-induced GCR events. Cells carrying the ChrXV-L GCR reporter chromosome were grown in the presence or absence of MMS and assayed for survival on media containing 5-FOA and canavanine. Data is represented as the average frequency of GCR events and standard error of the mean of 6 experiments.

These latter results are particularly intriguing since data linking H2A phosphorylation to genome stability in yeast are only starting to emerge. γ-H2A does not appear to impact gross chromosomal rearrangements (GCRs) using an assay employing ChrV-L39. Since GCR assays are often biased towards certain classes of genome rearrangements, we sought to identify an experimental context where γ-H2A promotes genome integrity. We therefore tested the effect of γ-H2A in a GCR assay that primarily examines break-induced replication (BIR) events on ChrXV-L36,40 (Fig. 4d), since BIR can restart replication forks after collapse41. We measured the frequency of GCR events in cells following treatment with methylmethane sulfonate (MMS), an agent that impairs replication fork progression42 and stimulates GCR formation43. As in the ChrV-L assay39, in the absence of exogenous DNA damage, the h2a-S129A mutations did not greatly impact GCRs at ChrXV-L (Fig. 4e). However, when replisome progression is impaired by MMS, the frequency of GCRs increases 14.2–fold in the h2a-S129A mutant versus 5.0–fold in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4e). Together, these data suggest that γ-H2A promotes genome integrity when replisome progression is impaired, but that this function is only apparent when large amounts of replication fork stalling occurs. In support of a role of γ-H2A in promoting genome integrity, recent work has shown that Tel1-induced H2A phosphorylation opposes the formation of break-induced translocations44. Therefore H2A phosphorylation, either by Mec1 or Tel1, can promote genome stability.

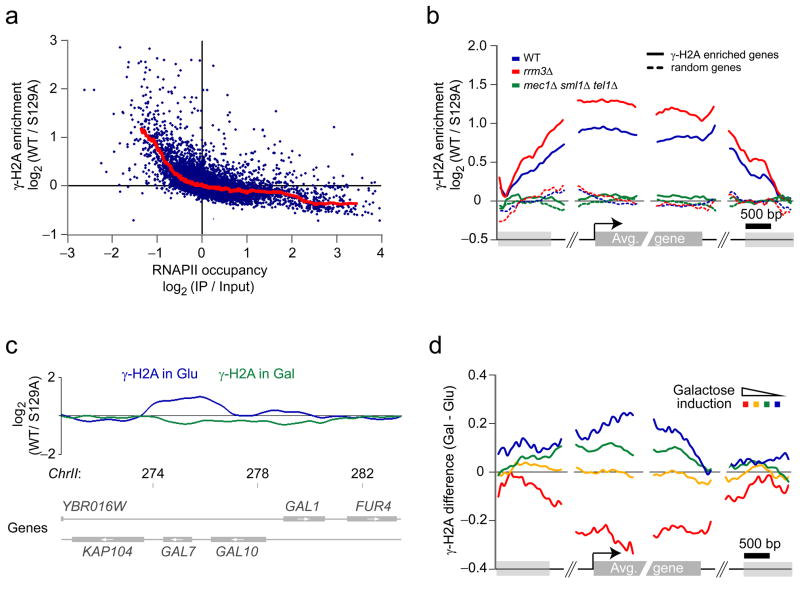

γ-H2A is enriched at actively repressed genes

The γ-sites described above correspond to known replisome barriers but accounted for only ~30% of the total number of loci identified in the ChIP-chip experiments. Surprisingly, most of the remaining γ-sites lie within or around protein-coding genes transcribed by RNA polymerase II (RNAPII). Using the same p value cutoff of 0.1, a total of 340 genes coincide partly or entirely with γ-sites (Supplementary Table 2). Analysis of the relationship between transcription and γ-H2A enrichment shows a clear anti-correlation between transcription (measured by RNAPII occupancy) and γ-H2A enrichment, calculated on the complete length of the genes (Fig. 5a). The anti-correlation is especially marked for the least transcribed genes. Poorly transcribed genes are therefore associated with higher levels of γ-H2A. Mapping of the γ-H2A signal on genes enriched for γ-H2A and on a random group of genes not displaying γ-H2A enrichment shows that γ-H2A accumulates over the entire length of the first group of genes (Fig. 5b). Similar to tRNA genes, DNA replication origins and LTRs, the averaged γ-H2A signal on these protein-coding genes is also more intense in rrm3Δ cells. Moreover, this γ-H2A enrichment is also Mec1- and Tel1-dependent (Fig. 5b) indicating that H2A phosphorylation over protein-coding genes arises from DNA damage signaling. Intriguingly, in asynchronously dividing cells, DNAP does not preferentially accumulate at repressed genes but instead is found at active genes (Supplementary Fig. 6), a finding recently corroborated by Azvolinsky and colleagues45.

Figure 5.

Many inactive genes display γ-H2A enrichment. (a) Anti-correlation between γ-H2A and RNAPII occupancy for the least transcribed genes. The average γ-H2A enrichment is plotted against RNAPII occupancy as determined by ChIP-chip in the same conditions. (b) γ-H2A accumulation at inactive genes is enhanced in rrm3Δ cells and is abolished in mec1Δ sml1Δ tel1Δ cells. The average γ-H2A enrichment ratios for WT (blue), rrm3Δ (red) and mec1Δ sml1Δ tel1Δ (green) cells are mapped relative to the 5′ and 3′ boundaries of protein-coding genes enriched for γ-H2A (solid curves) and on a random group containing the same number of genes (dashed curves). (c) Gene activation abolishes the accumulation of γ-H2A at repressed protein-coding genes. The smoothed γ-H2A enrichment ratios for cells grown in presence of glucose (blue) and galactose (green) are shown at the GAL7-10-1 locus. Chromosomal positions are indicated in kilobases. (d) The variation of γ-H2A level is correlated with galactose induction. The difference of γ-H2A enrichment ratios between cells grown in the presence of galactose (Gal) or glucose (Glu) is mapped (as in b) on groups of genes based on their fold change of expression in the presence of galactose27.

A clear example of a gene displaying γ-H2A enrichment is GAL7 (Fig. 5c, blue trace). GAL7 is repressed when cells are grown in media containing glucose as the carbon source and is actively transcribed when cells are grown in galactose46. This enrichment at GAL7 allowed us to test the causal relationship between transcription and the presence of γ-H2A. We therefore performed a γ-H2A ChIP-chip experiment on galactose-grown cells and observed that the γ-H2A signal at GAL7 is completely abolished (Fig. 5c, green trace). These results were also confirmed by qPCR (data not shown) and support a model whereby active repression results in H2A phosphorylation.

To test whether this observation is a general phenomenon or unique to GAL7 we binned genes in four groups according to their galactose inducibility27 and graphed the difference in their averaged γ-H2A enrichment ratios following galactose induction (Fig. 5d). Importantly, this analysis revealed that galactose-inducible genes generally lose their γ-H2A signal following galactose addition (Fig. 5d, red trace). Inversely, genes that are repressed in galactose tend to gain γ-H2A signal when grown in this carbon source (Fig. 5d, blue trace). Collectively, this data demonstrates that repressed genes are more prone to H2A phosphorylation than are active genes.

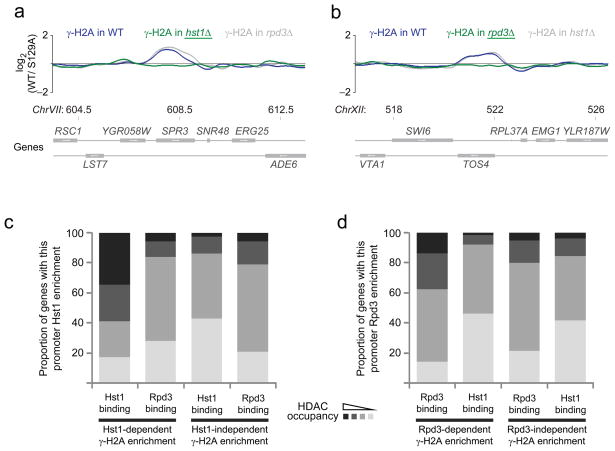

Accumulation of γ-H2A at inactive genes is HDAC-dependent

Not all inactive genes show evidence of γ-H2A accumulation. To identify a common theme between the RNAPII-transcribed genes associated with γ-H2A, we compared γ-H2A-enriched genes with previously published transcription factor binding sites based on ChIP-chip data47. Interestingly, the genes with high γ-H2A levels are enriched in those whose promoter is bound by the transcription factors Sum1 and Ume6 (Supplementary Table 4), which recruit histone deacetylases (HDACs)48–50. This analysis therefore suggested that some actively repressed genes may pose a special obstacle to DNA replication, likely due to a specialized chromatin structure involving HDACs. To investigate the role of HDACs in γ-site formation, we remapped γ-sites by ChIP-chip in cells lacking either Hst1 or Rpd3, two HDACs likely to play a role since they are recruited by Sum1 (Hst1) or Ume6 (Rpd3). Figure 6a,b show the γ-H2A signal at SPR3 and TOS4, two genes regulated by Hst1 and Rpd3, respectively. Consistent with this differential regulation, deletion of HST1 abolished the γ-signal at SPR3 but not at TOS4 (Fig. 6a). The inverse was seen for deletion of RPD3 (Fig. 6b). To confirm that the γ-H2A signal observed on Rpd3-regulated genes was due to its deacetylase activity, we mapped γ-sites in the catalytically inactive rpd3-H188A strain and found that its profile closely matched that of the rpd3Δ mutant (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.9, Supplementary Table 3). These results therefore suggest that a chromatin structure dependent on HDAC activity promotes Mec1- and Tel1-dependent H2A phosphorylation.

Figure 6.

γ-H2A accumulation at many inactive genes depends on HDAC activities. (a-b) The smoothed γ-H2A enrichment ratio is shown at selected Hst1 (a) and Rpd3 (b) target genes in WT cells (blue curves) and hst1 or rpd3 mutant (green curves) cells (the complementary mutant curves are in grey). Chromosomal positions are indicated in kilobases. (c-d) The deletion of Hst1 or Rpd3 preferentially affects γ-H2A enrichment at genes known to be physically associated with these HDACs according to previously published ChIP-chip data50.

Finally, we analyzed the gene ontology (GO)51 terms for genes that have a γ-site most strongly dependent on Hst1 and Rpd3 (Supplementary Table 5). Genes having a γ-H2A signal dependent on HST1 are enriched for GO terms related to sporulation, a process known to be regulated by Hst148. Similarly, genes whose γ-site is RPD3-dependent are enriched with GO categories related to cell cycle regulation and meiosis, two processes regulated by Rpd349,50,52,53. This data supports the idea that Hst1 and Rpd3 influence γ-H2A formation directly. Additionally, we separated genes containing a γ-site in two groups: those that were affected by the deletion of HST1 and those that were affected by the deletion of RPD3. Genes that harbor Hst1-dependent γsites tend to be direct targets of Hst1 but not of Rpd3 (Fig. 6c), while the Rpd3-dependent γ-sites are enriched in genes directly bound by Rpd3 but not Hst1 (Fig. 6d). Together, this data indicates that a HDAC-mediated chromatin structure elicits PIKK-dependent H2A phosphorylation and suggests that this chromatin structure might pose a problem for replisome progression or stability.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we surveyed the genome to identify loci displaying γ-H2A accumulation. Since Mec1 and Tel1 are responsible for γ-H2A formation in S. cerevisiae21, this study provides a high-resolution map of sites prone to PIKK activation in eukaryotes. We conclude that the great majority of γ-sites observed are the consequence of replication fork pausing, stalling or collapse based on a number of observations. Firstly, ~30% of the γ-sites map to known natural replication fork barriers such as tRNA genes, DNA replication origins, telomeres and LTRs. Secondly, γsites overlap with DNAP accumulation at these sites. Thirdly, deletion of RRM3 leads to an increase in γ-H2A accumulation at most γ-sites. Fourthly, our GCR and focus formation data support the idea that γ-H2A promotes replication fork stability (or restart). Finally, we showed that γ-sites, with one notable exception discussed below, are dependent on the combined action of Mec1 and Tel1, indicating that the loci mapped are prone to breakage. We therefore contend that high-resolution mapping of γ-H2AX provides a novel tool to analyze genome architecture.

Recent studies have identified fragile sites in yeast that are particularly sensitive to low levels of DNA polymerases12 or DNA damage checkpoint signaling8,10. Satisfyingly, these studies point to Ty elements, tRNA genes or DNA replication origins as the source of chromosome breakage. For example, we see at least two γ-sites at the 403 locus mapped by Admire et al. (Supplementary Fig. 5). Surprisingly, the peaks at the 403 locus are not more pronounced than the hundreds of other γ-sites we mapped. Our observation suggests that γ-sites (and replication fork pausing) are not the only determinants of the genome rearrangements observed in these studies.

Centromeric chromatin displays a unique property in that H2A phosphorylation at this locus is entirely Mec1-dependent and is also particularly labile, being totally absent from G1-synchronized cells. Why this is the case is currently unknown but we can speculate on two possible mechanisms that would impart Mec1 specificity to this class of γ-sites. Firstly, centromeric chromatin might be a replisome barrier that promotes Mec1 activity but does not make replication forks prone to collapse; possibly the resulting centromeric γ-site plays a role in centromere biology. A second possibility, albeit harder to explain, is that centromeric chromatin may be specifically refractory to Tel1 activity.

The link identified between histone deacetylation and H2A phosphorylation is perhaps the most unexpected finding of this study. Since H2A phosphorylation at silent genes arises from Mec1/Tel1-dependent signaling, it indicates that the chromatin structure promoted by HDACs may impede replisome progression. However, we and a recent study45 do not observe on average a major accumulation of DNAP on repressed genes. In contrast, DNAP clearly accumulates over active genes (Supplementary Fig. 6). This latter result indicates that replisome pausing at active genes must be managed effectively since it does not trigger Mec1/Tel1-dependent signaling. It will be interesting to determine what mechanism stabilizes replication forks at actively transcribed genes since work by Azvolinsky et al. have already excluded Rrm3 from having such a function45. We also note that histone acetylation has been reported to positively regulate the timing of late-origin firing54,55. Although it is not clear whether replication timing and the γ-sites seen at the HDAC-regulated genes are functionally linked, it may suggest that a relationship exists between replisome progression and origin firing. Additionally, our results suggest that mechanisms may exist that specifically promote replication through HDAC-repressed chromatin, and that a balance must be struck between the need for stable gene repression and replisome stability.

METHODS

Yeast strains

The strains used in this study are described in Supplementary Table 6. We constructed all strains using standard genetic techniques.

Antibodies

We obtained antibodies from the following sources: rabbit anti-yeast phospho-Ser129 H2A (γ-H2A), Millipore; mouse anti-myc (9E10), Santa Cruz or Covance; mouse anti-RNA polymerase II (8WG16), Covance; mouse anti-HA (F7), Santa Cruz; rabbit polyclonal yeast histone H4 antibody is a kind gift of Alain Verreault; normal rabbit serum was obtained from an unimmunized rabbit.

Chromatin immunoprecipitations and qPCR

We performed ChIP experiments essentially as described previously56. Briefly, we grew 50 mL of cells in XY + 2% (w/v) glucose36 until the culture reached mid-log phase. For galactose induction experiments we precultured cells in XY + glucose, washed them twice in water, and subcultured them into XY + 2% (w/v) galactose for 7 hours. Growth conditions for cell synchronization experiments are described below. Next, we incubated 800 μL of formaldehyde-fixed whole-cell extract with the appropriate antibody coupled to magnetic beads (Dynal Biotech, Brown Deer, WI). We used immunoprecipitated DNA either for genome-wide location analysis (see below) or qPCR analysis. For analysis of TEL06R, we performed qPCR with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on an ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System and analyzed the results as previously described57 using chromatin immunoprecipitated with normal rabbit serum as the control condition and TSC11 as the reference gene. For analysis of tS(GCU)L, we performed qPCR with the Quantitect SYBR Green PCR kit (QIAGEN) on a Stratagene Mx3005P. We determined enrichment at the tS(GCU)L locus after normalization against values obtained from input samples using the ARN1 locus, as well as normalizing for nucleosome density by histone H4 immunoprecipitation. The sequences of the oligonucleotides used for the qPCR experiments are available in Supplementary Table 7.

DNA labeling and hybridization

We amplified and labeled immunoprecipitated DNA as described previously56. We performed hybridization as described in Pokholok et al.58, using salmon sperm in place of herring sperm DNA. We purchased the microarrays used for location analysis from Agilent Technologies (Palo Alto, California, United States). The arrays contain a total of 44,290 Tm-adjusted 60-mer probes (including 2,306 controls), covering the entire genome (except for repetitive regions) for an average density of one probe every 275 bp (±100 bp) within the probed regions (catalog # G4486A and G4493A). Detailed scanning protocols are available from the GEO submission described above.

Data analysis

We normalized the data and combined the replicates using a weighted average method as described previously58. The procedure used to identify γ-sites listed in Supplementary Table 2 is based on statistically enriched regions and is described in the Supplementary Methods. We performed visual inspection of the enrichment ratios on the UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). To interpolate between probes, we applied a standard Gaussian filter (SD = 200 bp) to the data twice as described previously56. This will be referred to as “smoothed data”. We performed most of the mapping and correlation analyses as in Rufiange et al.59. Additional details are available in the Supplementary Methods. The location of DNA replication origins are defined as loci described as origins in oriDB60 (http://www.oridb.org, June 12 2007) and we refined their exact positions by ChIP-chip of the Mcm4 and Mcm7 components of the MCM complex (Supplementary File 1).

Cell synchronization and cell cycle profiling

For cell synchronization experiments, we precultured cells overnight in standard XY + 2% (w/v) glucose, subcultured them into 200 mL of XY (pH adjusted to 3.9) + 2% (w/v) glucose and grew them to an OD600 of 0.5–0.6. We enriched for G1 cells by exposure to α-factor (5 μg mL−1) for 2 h at 30°C prior to fixation for ChIP or FACS. To enrich for mid-S-phase cells, we washed α-factor-arrested cells twice in sterile water, released them into 200 mL standard XY + 2% (w/v) glucose, and fixed them for ChIP or FACS after 32 minutes of growth at 30°C. We determined cell cycle profiles by FACS as described36.

Ddc2-GFP and Rad52-YFP Focus Formation Assays

We examined cells expressing either Ddc2-GFP or Rad52-YFP for focus formation essentially as described by Kanellis et al36. We took micrographs in 8–10 z-stacks spanning 1–2 μm through the nucleus. For each strain, we examined 2–3 independent isolates. For each independent isolate, we examined a minimum of 100 cells. We counted foci by visually examining each focal plane. Further details are available in the Supplementary Methods.

Gross chromosomal rearrangement analysis

We performed MMS-induced GCR measurements essentially as described in Myung and Kolodner43. Briefly, we grew yeast cells from single colonies in media lacking uracil to select for the URA3-CAN1 ChrXV-L arm. We washed mid-log phase cells twice in water and treated them with 0.1% (v/v) MMS or dimethyl sulfoxide for 2h at 30 C. We washed the cells 3 times in water and resuspended them in 10 culture volumes of non-selective rich media (XY + 2% (w/v) glucose). After growth to saturation, cells were plated onto a 10 cm plate containing 1 g L−1 5-FOA and 60 mg L−1 canavanine and the frequency of resulting colony forming units was calculated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Durocher and Robert laboratories for their help and discussions. We also thank Nori Sugimoto (University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey), Rodney Rothstein (Columbia University), David Lydall (Newcastle University), Kim Nasmyth (University of Oxford), Angelika Amon (Massachussetts Insitute of Technoligy), William Bonner (National Cancer Institute), Karim Labib (Univeristy of Manchester), John Wyrick (Washington State University), Richard Young (Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research), Grant Brown (University of Toronto) and Alain Verreault (Université de Montréal) for the gift of strains, plasmids and antibodies and to Philippe Pasero (Institute of Human Genetics, CNRS) for kindly communicating unpublished results. DD is the Thomas Kierans Chair in Mechanisms of Cancer Development and holds a Canada Research Chair (Tier II) in Proteomics, Bioinformatics and Functional Genomics. FR holds a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. P-ÉJ holds a post-doctoral award from the IRCM training program in cancer research funded by the CIHR. This work was funded by grants from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute to DD and from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research to FR (MOP82891).

Footnotes

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The ChIP-chip data in this paper have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through GEO series accession number GSE18191.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RKS generated most yeast strains, and performed most ChIP-chip experiments as well as the TEL06R qPCR (assisted by MM) and GCR (assisted by SG) experiments. P-ÉJ analyzed all ChIP-chip data. LL performed the mutant tRNA qPCR experiment. Additional ChIP-chip experiments were performed by BC (wild-type and h2a-S129Aγ-H2A), ARB (MCMs) and MB (RNAPII). MY performed focus formation assays. DD and FR, with help from P-ÉJ and RKS, conceived the experiments and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Labib K, Hodgson B. Replication fork barriers: pausing for a break or stalling for time? EMBO Rep. 2007;8:346–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durkin SG, Glover TW. Chromosome fragile sites. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:169–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.042007.165900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivessa AS, et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae helicase Rrm3p facilitates replication past nonhistone protein-DNA complexes. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1525–36. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ivessa AS, Zhou JQ, Schulz VP, Monson EK, Zakian VA. Saccharomyces Rrm3p, a 5′ to 3′ DNA helicase that promotes replication fork progression through telomeric and subtelomeric DNA. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1383–96. doi: 10.1101/gad.982902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deshpande AM, Newlon CS. DNA replication fork pause sites dependent on transcription. Science. 1996;272:1030–3. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenfeder SA, Newlon CS. Replication forks pause at yeast centromeres. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:4056–66. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.9.4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha RS, Kleckner N. ATR homolog Mec1 promotes fork progression, thus averting breaks in replication slow zones. Science. 2002;297:602–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1071398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raveendranathan M, et al. Genome-wide replication profiles of S-phase checkpoint mutants reveal fragile sites in yeast. EMBO J. 2006;25:3627–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothstein R. Deletions of a tyrosine tRNA gene in S. cerevisiae Cell. 1979;17:185–90. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90306-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Admire A, et al. Cycles of chromosome instability are associated with a fragile site and are increased by defects in DNA replication and checkpoint controls in yeast. Genes Dev. 2006;20:159–73. doi: 10.1101/gad.1392506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roeder GS, Fink GR. DNA rearrangements associated with a transposable element in yeast. Cell. 1980;21:239–49. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lemoine FJ, Degtyareva NP, Lobachev K, Petes TD. Chromosomal translocations in yeast induced by low levels of DNA polymerase a model for chromosome fragile sites. Cell. 2005;120:587–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cliby WA, et al. Overexpression of a kinase-inactive ATR protein causes sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and defects in cell cycle checkpoints. EMBO J. 1998;17:159–69. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown EJ, Baltimore D. ATR disruption leads to chromosomal fragmentation and early embryonic lethality. Genes Dev. 2000;14:397–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinert TA, Kiser GL, Hartwell LH. Mitotic checkpoint genes in budding yeast and the dependence of mitosis on DNA replication and repair. Genes Dev. 1994;8:652–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.6.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paulovich AG, Hartwell LH. A checkpoint regulates the rate of progression through S phase in S. cerevisiae in response to DNA damage. Cell. 1995;82:841–7. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun Z, Fay DS, Marini F, Foiani M, Stern DF. Spk1/Rad53 is regulated by Mec1-dependent protein phosphorylation in DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways. Genes Dev. 1996;10:395–406. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desany BA, Alcasabas AA, Bachant JB, Elledge SJ. Recovery from DNA replicational stress is the essential function of the S-phase checkpoint pathway. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2956–70. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopes M, et al. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature. 2001;412:557–61. doi: 10.1038/35087613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogakou EP, Pilch DR, Orr AH, Ivanova VS, Bonner WM. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Downs JA, Lowndes NF, Jackson SP. A role for Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone H2A in DNA repair. Nature. 2000;408:1001–4. doi: 10.1038/35050000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster ER, Downs JA. Histone H2A phosphorylation in DNA double-strand break repair. FEBS J. 2005;272:3231–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernandez-Capetillo O, Lee A, Nussenzweig M, Nussenzweig A. H2AX: the histone guardian of the genome. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:959–67. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cobb JA, et al. Replisome instability, fork collapse, and gross chromosomal rearrangements arise synergistically from Mec1 kinase and RecQ helicase mutations. Genes Dev. 2005;19:3055–69. doi: 10.1101/gad.361805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ward IM, Chen J. Histone H2AX is phosphorylated in an ATR-dependent manner in response to replicational stress. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47759–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redon C, et al. Yeast histone 2A serine 129 is essential for the efficient repair of checkpoint-blind DNA damage. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:678–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren B, et al. Genome-wide location and function of DNA binding proteins. Science. 2000;290:2306–9. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shroff R, et al. Distribution and dynamics of chromatin modification induced by a defined DNA double-strand break. Curr Biol. 2004;14:1703–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JA, Kruhlak M, Dotiwala F, Nussenzweig A, Haber JE. Heterochromatin is refractory to gamma-H2AX modification in yeast and mammals. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:209–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Vujcic M, Kowalski D. DNA replication forks pause at silent origins near the HML locus in budding yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4938–48. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.4938-4948.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Azvolinsky A, Dunaway S, Torres JZ, Bessler JB, Zakian VA. The S. cerevisiae Rrm3p DNA helicase moves with the replication fork and affects replication of all yeast chromosomes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3104–16. doi: 10.1101/gad.1478906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torres JZ, Schnakenberg SL, Zakian VA. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rrm3p DNA helicase promotes genome integrity by preventing replication fork stalling: viability of rrm3 cells requires the intra-S-phase checkpoint and fork restart activities. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:3198–212. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.8.3198-3212.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothstein R, Helms C, Rosenberg N. Concerted deletions and inversions are caused by mitotic recombination between delta sequences in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1198–207. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.3.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melo JA, Cohen J, Toczyski DP. Two checkpoint complexes are independently recruited to sites of DNA damage in vivo. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2809–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.903501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lisby M, Rothstein R, Mortensen UH. Rad52 forms DNA repair and recombination centers during S phase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8276–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121006298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanellis P, et al. A screen for suppressors of gross chromosomal rearrangements identifies a conserved role for PLP in preventing DNA lesions. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sollier J, et al. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Esc2 and Smc5–6 proteins promote sister chromatid junction-mediated intra-S repair. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1671–82. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mankouri HW, Ngo HP, Hickson ID. Esc2 and Sgs1 act in functionally distinct branches of the homologous recombination repair pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1683–94. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Myung K, Pennaneach V, Kats ES, Kolodner RD. Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromatin-assembly factors that act during DNA replication function in the maintenance of genome stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6640–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232239100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hackett JA, Feldser DM, Greider CW. Telomere dysfunction increases mutation rate and genomic instability. Cell. 2001;106:275–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kraus E, Leung WY, Haber JE. Break-induced replication: a review and an example in budding yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8255–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151008198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tercero JA, Longhese MP, Diffley JF. A central role for DNA replication forks in checkpoint activation and response. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1323–36. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Myung K, Kolodner RD. Induction of genome instability by DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:243–58. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00216-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee K, Zhang Y, Lee SE. Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATM orthologue suppresses break-induced chromosome translocations. Nature. 2008;454:543–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Azvolinsky A, Giresi PG, Lieb JD, Zakian VA. Highly transcribed RNA polymerase II genes are impediments to replication fork progression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell. 2009;34:722–734. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Broach JR. Galactose regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The enzymes encoded by the GAL7, 10, 1 cluster are co-ordinately controlled and separately translated. J Mol Biol. 1979;131:41–53. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.MacIsaac KD, et al. An improved map of conserved regulatory sites for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie J, et al. Sum1 and Hst1 repress middle sporulation-specific gene expression during mitosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1999;18:6448–54. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kadosh D, Struhl K. Repression by Ume6 involves recruitment of a complex containing Sin3 corepressor and Rpd3 histone deacetylase to target promoters. Cell. 1997;89:365–71. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robert F, et al. Global position and recruitment of HATs and HDACs in the yeast genome. Mol Cell. 2004;16:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–9. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inai T, Yukawa M, Tsuchiya E. Interplay between chromatin and trans-acting factors on the IME2 promoter upon induction of the gene at the onset of meiosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1254–63. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01661-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Veis J, Klug H, Koranda M, Ammerer G. Activation of the G2/M-specific gene CLB2 requires multiple cell cycle signals. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8364–73. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01253-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aparicio JG, Viggiani CJ, Gibson DG, Aparicio OM. The Rpd3-Sin3 histone deacetylase regulates replication timing and enables intra-S origin control in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4769–80. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.4769-4780.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vogelauer M, Rubbi L, Lucas I, Brewer BJ, Grunstein M. Histone acetylation regulates the time of replication origin firing. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1223–33. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00702-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guillemette B, et al. Variant histone H2A.Z is globally localized to the promoters of inactive yeast genes and regulates nucleosome positioning. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pokholok DK, et al. Genome-wide map of nucleosome acetylation and methylation in yeast. Cell. 2005;122:517–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rufiange A, Jacques PE, Bhat W, Robert F, Nourani A. Genome-wide replication-independent histone H3 exchange occurs predominantly at promoters and implicates H3 K56 acetylation and Asf1. Mol Cell. 2007;27:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nieduszynski CA, Hiraga S, Ak P, Benham CJ, Donaldson AD. OriDB: a DNA replication origin database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D40–6. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.