Abstract

Although corneal transplantation is readily available in the USA and certain other regions of the developed world, the need for human donor corneas worldwide far exceeds supply. There is currently renewed interest in the possibility of using corneas from other species, especially pigs, for transplantation into humans (xenotransplantation). The biomechanical properties of human and pig corneas are similar. Studies in animal models of corneal xenotransplantation have documented both humoral and cellular immune responses that play roles in xenograft rejection. The results obtained from the Tx of corneas from wild-type (i.e., genetically-unmodified) pigs into nonhuman primates have been surprisingly good and encouraging. Recent progress in the genetic manipulation of pigs has led to the prospect that the remaining immunological barriers will be overcome. There is every reason for optimism that corneal xenoTx will become a clinical reality within the next few years.

Keywords: Cornea, biomechanics; Cornea, pig; Cornea, immune response; Pig, genetically-engineered; Transplantation, cornea; Xenotransplantation, cornea

Introduction

Clinical corneal transplantation (Tx) enjoys considerable success (Table 1), particularly in uncomplicated patients with non-vascularized native corneas 1–3. However, in high-risk patients with inflamed and/or vascularized corneas, the survival rate is lower, even with topical and/or systemic immunosuppression (Table 1) 2.

Table 1.

Corneal allograft survival in humans *

| Low Risk | High Risk** | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 93% | 77% |

| 5 year | 86% | 56% |

| 10 year | 76% | 41% |

Reported by the Australian Corneal Graft Registry, 2007

High-risk patients with inflamed and/or vascularized corneas.

Although corneal Tx is readily available in the USA and in certain other regions of the developed world, the worldwide need for human donor corneas far exceeds supply (Table 2). In some parts of Asia, especially China, Korea, and Japan, where cultural and religious concerns make it difficult to obtain corneas from human cadavers, severe shortages of donor corneas persist 4. In some parts of the world, the pig as a source of corneas may be unacceptable on religious grounds (e.g., Islam, Judaism, Jainism). However, beliefs often vary within religious groups or on an individual basis. Furthermore, for example, although the prohibition of pork for consumption is mentioned in the Holy Qur’an, there is no definitive comment on the use of pig tissues or organs for therapeutic purposes. Discussion with representatives of these religious groups will be required to enable guidelines to be drawn up.

Table 2.

Corneal allotransplantation in 2008*

| Country | Estimated number of cases per year | Waiting List |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 41,652 | 0 |

| United Kingdom | 2,711 | 500 |

| South Africa | 330 | 1884 |

| India | 15,000 | 300,000 |

| China | 101 | 4,000,000 |

| Taiwan | 263 | 637 |

| Korea | 480 | 3,630 |

| Japan | 1,634 | 2,769 |

| Australia | 1,096 | 0 |

Based on Eye Bank data in individual countries and personal communications

In addition, the availability of corneas can change over time. For example, although there was no shortage in the past in South Africa (799 donated corneas in 2005), there has been significantly decreased availability recently (330 in 2008), largely because of the high incidence of infectious diseases in potential donors, particularly human immunodeficiency virus. Even in the developed world, the increasing popularity of refractive surgery will reduce the supply of human corneas 5,6; current Eye Bank Association of America standards do not allow the use of corneas that have been subjected to surgery for penetrating keratoplasty, although they can be used for tectonic grafting and posterior lamellar procedures.

The potential of corneal xenotransplantation

In addressing this shortage, animal corneas might prove acceptable substitutes. XenoTx, using pigs as the source animal, offers the potential of an unlimited number of organs, tissues, and cells for Tx into humans 7,8. There are many similarities between pigs and humans in regard to anatomy and physiology 9–11 (Table 3 and Figure 1). Ethically, pigs represent an acceptable choice as an alternative source of organs for humans 12,13. Immunologically, however, the pig is less desirable than the nonhuman primate as a source because of the genetic distance between pigs and humans. However, because the cornea is an immune-privileged tissue and is not immediately vascularized, its fate as a xenograft is likely to be better than that of organ xenografts 7,14. Furthermore, advances in the genetic-engineering of pigs are steadily enabling their tissues to become resistant to injury from the primate immune response 7,8. Indeed, selected genetic modifications to the source pig may render the cornea comparable, or even superior, to a human cornea with regard to its ability to resist rejection, even in the absence of local steroid therapy.

Table 3.

Comparison of corneas between human and pig

| Human | Pig | Source (reference) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter (mm) | ||||

| horizontally | 11.7 | 14.9 | (11) | |

| vertically | 10.6 | 12.4 | ||

| Thickness(μm) | (9), (10) | |||

| center | 536 | 666 | ||

| periphery | 593 | 714 | ||

| Refractive power (Diopter) | 43.0 | 40.4 | (10) | |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 3.81 | 3.70 | (104) | |

| Stress-strain | α | 42.8 | 39.3 | (104) |

| Pattern* | β | 2.97 | 2.97 | |

| Stress-relaxation | P(x100) | 85.6 | 64.6 | (104) |

| Pattern ** | K(-) | 0.0165 | 0.0553 | |

| 1000s | 32.0% | 59.2% | (106) |

α is a scale factor

β represents the exponent of the nonlinear relationship between stress and strain

P is the value of G (t) at the end of the stress-relaxation test

K is the slope of fitted G (t)-In t line

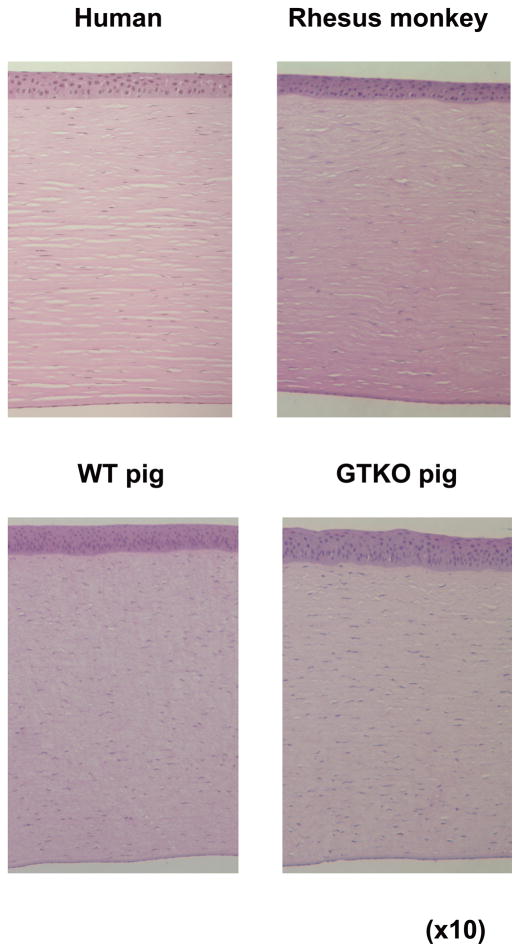

Figure 1.

Comparison of histological structure of the cornea in human, rhesus monkey, wild-type pig, and α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout (GTKO) pig.

Pigs can be bred and housed in a ‘clean’ environment, and can be closely monitored, that would prevent the risk of transfer of potentially-infectious agents with the cornea. The potential risk of transfer of porcine endogenous retroviruses to the recipient, and possibly to the recipient’s contacts 15–17, is now believed to be very small and acceptable if the potential benefits to the recipient are anticipated to be considerable 18. The special housing required for the pigs to be used for clinical purposes could be provided in a small number of facilities in developed countries, and the corneas mailed to wherever required, including less well-developed countries. Unlike deceased human corneas, pig corneas would be known to be definitively free of pathogenic microorganisms.

Clinical experience with corneal xenotransplantation

There have been several attempts to use animal corneas for Tx in humans, beginning in the early 19th century 19. These have involved corneas from pigs, sheep, dogs, rabbits 20–24, and, in the 20th century, from gibbons, cows, and fish 25–27. The first clinical corneal xenoTx (in 1838) was performed by Kissam 20, more than half a century before the first corneal alloTx, which was carried out by Zirm in 1905 28–30. Although several xenotransplants were reported to be technically successful, most of the xenografts from widely-disparate species were rejected within one month.

Although the results of the Tx of the corneas from gibbons were encouraging (50% of the corneas remained transparent for >5 months) 25, the use of nonhuman primates as sources of grafts for human recipients has largely been excluded 12,13. Nonhuman primates exhibit limited reproductive capacity and availability, and, because of the potential risk of transfer of viruses, e.g., those related to the HIV family, present a possible health risk to human recipients. Furthermore, the use of species with many behavioral similarities to humans would be ethically unacceptable to a segment of society.

Experimental corneal xenotransplantation in nonhuman primates

There is an extensive literature on experimental corneal xenoTx in both large and small animal models. However, there have been very few recent studies in the clinically-relevant pig-to-nonhuman primate Tx model. Pan and his colleagues 31 carried out a study of wild-type (i.e., unmodified, WT) pig corneal transplants in rhesus monkeys. They reported that grafts in untreated (non-immunosuppressed) monkeys were rejected within 15 days, though hyperacute rejection was not seen. The rejected xenografts showed inflammatory cell infiltrates in the anterior part of the stroma, and absent or abnormal endothelium, which suggested that corneal endothelium may be a major target for immune factors, such as antibodies or complement in the aqueous humor, or cells such as T cells and macrophages. Remarkably, subconjunctival injections of a corticosteroid (betamethasone) every 10 days for 3 months prolonged survival for several months. The authors did not investigate antibody deposition on the graft or serum levels of anti-pig antibodies after rejection. This result, if confirmed, is very encouraging for the use of pig corneas in clinical practice. However, it would be ideal if corneal xenoTx did not require prolonged immunosuppressive therapy of any sort. The Tx of corneas from genetically-modified pigs might enable this goal to be achieved.

The immune response to corneal xenografts

The mechanisms of rejection of a corneal xenograft are significantly different from those of a vascularized organ xenograft 32. The immune privileged environment of the cornea appears to provide corneal xenografts with some degree of protection 33.

Since the cornea is an avascular tissue, hyperacute rejection, which results form vascular occlusion and is commonly seen in vascularized solid organ xenografts 34, has not been seen in corneal xenografts in either small or large animal models 31,35–38. However, corneal endothelial cells appear to be highly susceptible to lysis by complement-fixing antibody 39,40 because of the lack of complement-regulatory proteins (CRP) on these cells 41. Complement may also contribute to rejection through the antibody-independent, alternative pathway 42.

The humoral response

WT pig corneas express Galα1,3Gal (Gal), the major porcine antigen against which nonhuman primates and humans have preformed (natural) antibodies 43–47. This is mostly confined to the anterior stromal keratocytes 48,49. Gal expression is gradually induced on corneal stroma and endothelial cells during in vitro culture and after pig-to-rat corneal Tx 49. Binding of anti-Gal antibodies to pig cells in vitro results in rapid complement-mediated destruction of the cells 50. In experimental organ xenoTx, this injury can be delayed by intensive immunosuppressive therapy, but this would not be an option with corneal grafts. If a corneal graft is placed into a high-risk patient, e.g., with a neovascularized and inflamed host bed, preformed anti-pig antibodies, particularly anti-Gal antibodies, will gain immediate access to the graft and will almost certainly reduce graft survival. In the long-term, therefore, the Tx of corneas from WT pigs is likely to be problematic, even under cover of topical steroids and/or systemic immunosuppression.

Clinical studies suggest that, in some instances, antibodies may contribute to corneal allograft failure if the recipient has been sensitized previously to donor alloantigens. Similarly, sensitization to xenoantigens has been detrimental to graft survival in rodent models of xenoTx 35,51. This is, at least in part, a byproduct of the T cell-mediated response generated to the graft. However, importantly, the current evidence, though limited, is that sensitization to pig antigens, e.g., following pig corneal xenoTx, would not result in the generation of anti-pig antibodies that might cross-react with alloantigens, and therefore prohibit subsequent corneal alloTx 52. Similarly, sensitization to an allograft would not be detrimental to a subsequent pig xenograft 52.

Current advances in the genetic-engineering of pigs have resulted in pigs that do not express the Gal epitope (α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout [GTKO] pigs) 53,54. The availability of these pigs will allow conclusions to be drawn with regard to the role of anti-Gal antibodies in the humoral rejection of the pig cornea. Preliminary data from our own laboratory indicate that the human humoral immune response to GTKO corneal cells is significantly weaker than to WT pig cells (Hara H, manuscript in preparation). Pigs also express other (nonGal) antigens, against which there is a weaker antibody-dependent complement-mediated response 50,55. It is difficult to determine the nature of the nonGal antigens that are present on pig corneas, although the presence of N-glycolylneuraminic acid is likely 52,56–60.

The cellular response

Immune-mediated destruction of corneal allografts and xenografts is primarily CD4+T cell-mediated and targets the corneal endothelial cell 32,37,61. CD8+T cells and natural killer T cells may play a role in rejection when CD4+T cells are absent or their function is impaired 62. The immune response to corneal xenografts appears to occur almost exclusively by the indirect pathway 63, i.e., the conventional route for presentation of foreign antigen to T cells via host antigen-presenting cells. There is a resident myeloid corneal dendritic cell population that normally does not express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II antigens, but can readily up-regulate class II expression during inflammation 64. Thus, it is likely that a population of passenger leukocytes in xenogeneic corneas is involved in direct xenoantigen presentation to host T cells as takes place in the allo-immune response 65. One of the costimulatory interactions occurs between CD28 (on the surface of T cells) and the B7 ligands, CD80 and CD86 (on antigen-presenting cells). Porcine endothelium, unlike human endothelium, constitutively expresses CD80 and CD86, and is fully capable of stimulating a human T cell response through the direct pathway, providing the potential for full human T cell activation at the donor endothelial cell surface 66.

In models of corneal allograft rejection, strong expression of the genes for IL-2 and IFN-γ and low expression of genes for IL-4 and IL-10 have been described 67,68. This observation underlines the role of the Th1 response in corneal allograft rejection. However, abundant Th2 cytokine genes (IL-4 and IL-10) are expressed, in addition to expression of Th1 cytokine genes 69. The rejection of xenogeneic corneal grafts appears to be mediated by proinflammatory cytokines, especially IFN-γ, that are released by CD4+ and/or CD8+ T cells at the graft site 33,69.

In addition to these cytokines, rejected xenografts are significantly associated with expression of the genes for inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and with nitric oxide (NO) production. The presence of iNOS and NO, the main effector molecules responsible for macrophage-mediated cytotoxicity, can be considered as indirect evidence for the role of macrophages in corneal xenograft rejection. Infiltration of macrophages in the graft and aqueous humor has been observed when the graft is rejected 31. The role of macrophages in corneal allograft rejection has been well-documented 70, and depletion of macrophages at the time of corneal Tx prolongs graft survival 71. It is likely that macrophages play a similar role in the rejection of xenografts31.

In view of the humoral and cellular immune barriers, it is likely that successful corneal xenoTx will require the use of corneas from pigs with multiple genetic modifications (see below).

Immune privilege relating to corneal xenografts

Immune privilege is well-documented in relation to the eye, brain, ovary, testis, adrenal cortex, and certain solid tumors, as well as in the fetus in pregnancy 72. It is thought to be an evolutionary adaptation to protect vital structures from the potentially damaging effects of an inflammatory immune response. In the eye, the cornea, anterior chamber, vitreous cavity, and sub-retinal space are all considered to be immune-privileged sites.

The mechanisms that underlie immune privilege of corneas have been reviewed 1,3,72,73. They include an absence of blood vessels and lymphatics, weak expression of major histocompatibility complex antigens, expression of Fas ligand (FasL, CD95L) and programmed death ligand 1(PD-L1) 74,75, few (immature) antigen-presenting cells, and the presence of immunomodulating molecules, such as IL-10, TGF-beta, and complement-regulatory proteins (CRPs) in the aqueous humor.

However, immune privilege of the cornea is relative. With the exception of patients with corneal dystrophies, such as keratoconus, most keratoplasty patients have corneal graft beds that have lost their immune privilege from previous inflammation, neovascularization, trauma, or infections 2. This may predispose to rejection of a corneal allograft 76, and this is likely to be even more so in the case of a corneal xenograft.

Of potential importance to xenoTx, levels of complement components in aqueous humor are less than those in serum, although they can be increased in the presence of inflammation 41. Furthermore, several CRPs have been demonstrated to be expressed constitutively in the cornea, particularly in the epithelium, including decay-accelerating factor, C1 inhibitor, beta 1H, and C3b inhibitor 41,77. These CRPs protect autologous cells from complement-mediated injury. Unlike complement, some these molecules are highly species-specific. The absence of CRPs of the appropriate species on a corneal xenograft may thus act to augment complement-mediated damage, and help to explain why antibody plays a more important role in corneal xenograft rejection than it does in allograft rejection.

Many of the complement pathway components have been shown to be present in tears78, aqueous humor 77,78, and cornea 42,77 of normal humans. Strong expression of each of the CRPs, such as CD46, CD55 and CD59, has been demonstrated in human corneal epithelium, but not endothelium. The endothelium, therefore, might be a particular target for complement. Thus, graft injury by recipient complement is likely to occur unless recipient CRPs (e.g., human) are expressed on xenograft cells. Pigs are now available that express one or more human CRPs 50,79–83.

Genetic-engineering of pigs

There have been significant advances in recent years in the genetic-engineering of pigs. It is now possible to knock-out a gene as well as insert one or more genes. Pigs expressing a human CRP, such as decay-accelerating factor (DAF, CD55) 79 or membrane cofactor protein (MCP, CD46) 82, that provide considerable protection against primate complement-mediated injury, have been available through microinjection techniques for several years 79. However, nuclear transfer/embryo transfer offers greater possibilities as the gene can be deleted or inserted at a specific site.

The first WT (unmanipulated) pig was cloned in 2000 84. Pigs homozygous for GTKO were first produced in 2003 53,54. In these pigs, the gene for the enzyme, α1,3-galactosyltransferase, that produces the Gal saccharide - that is the major target for primate anti-pig antibodies – has been deleted. GTKO pigs, therefore, lack this major antigen.

Primate natural antibodies can also be directed to antigens other than Gal (nonGal antigens), though the level of antibody directed towards these antigens is significantly less than that directed to Gal 55,85,86. Anti-nonGal antibodies can, however, result in rejection of a pig organ graft in a nonhuman primate 87,88. As this rejection is mediated by complement, it can largely be prevented by the expression of a human CRP on GTKO pig cells 50,83.

Several pigs with genetic modifications of relevance to xenoTx have been produced, e.g., (i) GTKO pigs transgenic for CD46 50,83; (ii) GTKO pigs transgenic for the porcine costimulatory blockade agent, porcine cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4-Ig (pCTLA4-Ig)89, that provides local immunosuppresion against the T cell response (although these pigs produce so much CTLA4-Ig that they become immune-incompetent, resulting in repeated infectious complications); (iii) dominant-negative class II transactivator gene mutant pigs, in which upregulation of swine leukocyte antigen (SLA) class II expression on vascular endothelial cells after activation is suppressed, thus protecting the cells from injury induced by primate CD4+T cells (Hara H, et al, manuscript in preparation); (iv) pigs expressing ‘anticoagulant’, ‘anti-inflammatory’, and ‘anti-apoptotic genes, e.g., tissue factor pathway inhibitor (Phelps C, personal communication), CD39 (d’Apice A, personal communication), thrombomodulin 90,91, A20 92 and hemoxygenase-I (HO-1)93,94.

Increasingly, therefore, pigs with multiple genetic modifications of relevance to xenoTx are becoming available. Our initial in vitro studies on corneal endothelial cells from GTKO/CD46 pigs are encouraging, and will be reported fully elsewhere (Hara H, et al, manuscript in progress); in brief, they demonstrate a much greater resistance to the human humoral and cellular immune responses than WT pig corneal endothelial cells. It is not unduly optimistic to suggest that multiple manipulations will in the relatively near future provide pigs with corneas completely protected from the human innate and adaptive immune responses.

Anatomical and biomechanical considerations

Even if the immunologic barriers can be overcome, the question arises of whether the structure and biomechanical parameters of the porcine cornea are sufficiently similar to those of the human cornea to provide an alternative source for Tx. In view of the difficulty of obtaining human corneas in sufficient numbers for studies of the mechanical properties of corneas, animal corneas have been investigated as potential models. Several of these studies have involved pig corneas, and provide data of value in assessing the suitability of pig corneas for clinical xenoTx 95–99.

Pig corneal diameter, thickness, and refractive power have been compared with those of human corneas 9–11 (Table 3). As the mean pig corneal diameter is larger than that of humans, and in corneal Tx usually only the central 6–8mm of the cornea is grafted, the diameter of the pig cornea is adequate. The pig cornea, although consisting of the same 5 basic layers as the primate cornea, is slightly thicker. The primate corneal epithelium is stratified into 5 cellular layers, whereas the pig corneal epithelium is slightly thicker, consisting of 7–9 cell layers 100 (Figure 1). The pig cornea has a Bowman’s layer similar to that in a human 101,102. The refractive power of the pig cornea is not different from that of a human cornea 10. By testing freeze-thaw-induced damage, Oh et al. 103 demonstrated that pig corneal stroma was similar to that in the human.

Zeng et al 104 measured tensile strength, stress-strain relationship, and stress-relaxation properties in both human and porcine corneas (Table 3). The tensile strength and stress-strain relation were very similar, but significant differences between human and pig tissues were observed in the stress-relaxation relationship. Porcine corneas relaxed much more than human corneas. However, this difference may be a function of the relative ages of the corneas tested or of the methods of storage. Two further studies shed some light on this possibility.

Ahearne et al 105 demonstrated that porcine corneas were physically weaker than human corneas and had a more linear loading-unloading cycle. However, they suspected that the storage conditions of the corneas influenced strength, and that investigation into the influence of the storage media and conditions on the mechanical properties of the cornea might provide a better understanding of such physiochemical-mechanical interplays. Furthermore, when placed in a storage solution, porcine corneas appeared to swell more quickly than human corneas. Swelling reduced the strength of both corneas, but again the authors suggested that the storage media and conditions may play important roles in the rate of corneal swelling. They concluded that porcine corneas appeared to be less stiff and to demonstrate more linear response than human corneas under loading.

Elsheikh et al 106 concluded that human and porcine corneas had almost the same responses under short-term and long-term loading. They both exhibited non-linear stress-strain behavior and reacted to sustained loading in a similar fashion. However, because human corneas were significantly stiffer than porcine corneas, they could maintain their stress state for longer. In the authors’ opinion, these differences cast doubt on the suitability of porcine corneas as models for human corneas in mechanical studies.

Under short-term inflation testing, both human and porcine corneas demonstrated hyper-elastic behavior with an initial low stiffness and a final high stiffness. However, while human corneas experienced a non-linear behavior with a gradually increasing stiffness, porcine corneas appeared to have more of a bi-linear behavior with a distinct change in stiffness at about 10 mm Hg posterior pressure. Porcine corneas also appeared to have lower stiffness at all behavior stages compared to human corneas, though this could have been related to the relatively higher age of the human corneas tested.

In summary, this study suggested that porcine corneas appeared to be less able to maintain their initial shape or stress condition compared to human corneas. Porcine corneas deformed approximately twice as much as human corneas under ‘creep’ testing. In stress-relaxation tests, the stress reductions experienced by porcine corneas were again almost twice those observed in human corneas (Table 3) 106.

When human corneas were divided according to age, there was a gradual and significant stiffening with age under short-term loading, correlating with an earlier study by this group 107, and a gradual reduction in both creep strain and stress-relaxation. The confirmed age-related short-term stiffening and the possible long-term stiffening could have contributed to the differences reported in this study between the relatively old human corneas and the young porcine corneas. In vivo experimental data are required to compare the biomechanical features of corneas from humans and pigs of similar ages.

There is not a large body of data supporting the idea that the stiffness properties of a cornea are essential for its visual function. The stiffness and flexibility of the cornea, limbus, and sclera differ from one another, suggesting that consistency of this property is not an essential factor in maintenance of the integrity of the globe. In summary, therefore, the evidence is that age-matched human and porcine corneas show sufficient similarity in biomechanical parameters to suggest that porcine corneas are likely to provide a successful alternative to human corneas in this respect.

Finally, considering strength, it is important to consider that the cornea itself is not the weakest component of the system. The porcine corneas are to be used in full-thickness keratoplasty, a procedure which weakens the eye. Several studies 108,109 as well as anecdotal evidence from surgeons indicate that mechanical failure (globe rupture) of full thickness grafts inevitably occurs at the suture line between the graft and the host. This failure most frequently occurs in the first months after Tx, but can occur decades later. The strength of the globe appears to be permanently compromised by keratoplasty. The relatively small difference between the strength of human and porcine corneas is certainly a factor to be considered, but the strength of the cornea from either source greatly exceeds the strength of the suture bond between the grafted and host tissue. Consequently, although consideration of the differences in biomechanical properties of the corneas is warranted, there seems little justification to exclude the use of pig corneas for clinical Tx based on their known differences in biomechanical properties.

Conclusions

Disease of the cornea is a major cause of blindness worldwide. The worldwide need for corneal Tx far exceeds the supply of deceased human donor corneas. Successful acceptance of pig corneas is more likely than for pig organ xenografts due to the lack of immediate revascularization, and thus an absence of hyperacute rejection. The results obtained from the Tx of corneas from WT pigs into nonhuman primates have been surprisingly good and encouraging. Considerable effort is currently being expended in developing genetically-engineered pigs that should prove greatly-preferable sources of corneas for clinical Tx. There appear to be no overwhelming biomechanical differences between pig and human corneas that might prohibit xenoTx. There is every reason for optimism that corneal xenoTx will become a clinical reality within the next few years.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Eye Bank Association of America. Work on xenotransplantation in the Thomas E. Starzl Transplantation Institute of the University of Pittsburgh is supported in part by NIH grants U01 AI068642 and R21 A1074844, and by Sponsored Research Agreements between the University of Pittsburgh and Revivicor, Inc., Blacksburg, VA, USA.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CRP

complement-regulatory protein

- Gal

Galα1,3Gal

- GTKO

α1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout

- Tx

transplantation

- WT

wild-type

- xenoTx

xenotransplantation

References

- 1.Niederkorn JY. The immune privilege of corneal allografts. Transplantation. 1999;67:1503–1508. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199906270-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coster DJ, Williams KA. The impact of corneal allograft rejection on the long-term outcome of corneal transplantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:1112–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chong EM, Dana MR. Graft failure IV. Immunologic mechanisms of corneal transplant rejection. Int Ophthalmol. 2008;28:209–222. doi: 10.1007/s10792-007-9099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coster DJ, Williams KA. Donor cornea procurement: some special problems in Asia. Asia-Pacific J Ophthalmol. 1992;4:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michaeli-Cohen A, Lambert AC, Coloma F, et al. Two cases of a penetrating keratoplasty with tissue from a donor who had undergone LASIK surgery. Cornea. 2002;21:111–113. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200201000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mifflin M, Kim M. Penetrating keratoplasty using tissue from a donor with previous LASIK surgery. Cornea. 2002;21:537–538. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200207000-00024. author reply 538–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper DK, Dorling A, Pierson RN, 3rd, et al. Alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase gene-knockout pigs for xenotransplantation: where do we go from here? Transplantation. 2007;84:1–7. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000260427.75804.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tai HC, Ezzelarab M, Hara H, et al. Progress in xenotransplantation following the introduction of gene-knockout technology. Transpl Int. 2007;20:107–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2006.00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doughty MJ, Zaman ML. Human corneal thickness and its impact on intraocular pressure measures: a review and meta-analysis approach. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;44:367–408. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00110-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee HI, Kim MK, Ko JH, et al. The Characteristics of Porcine Cornea as a Xenograft. J Korean Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;47:2020–2029. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Faber C, Scherfig E, Prause JU, et al. Corneal thickness in pigs measured by ultrasound pachymetry in vivo. Scand J Lab Anim Sci. 2008;35:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooper DK, Ye Y, Rolf LJ, et al. Xenotransplantation. Chapter 30. Heideiberg: 1991. The pig as potential organ donor for man; pp. 481–500. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper DK, Gollackner B, Sachs DH. Will the pig solve the transplantation backlog? Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:133–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pierson RN, 3rd, Dorling A, Ayares D, et al. Current status of xenotransplantation and prospects for clinical application. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:263–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00534.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onions D, Cooper DK, Alexander TJ, et al. An approach to the control of disease transmission in pig-to-human xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2000;7:143–155. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3089.2000.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patience C, Patton GS, Takeuchi Y, et al. No evidence of pig DNA or retroviral infection in patients with short-term extracorporeal connection to pig kidneys. Lancet. 1998;352:699–701. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04369-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paradis K, Langford G, Long Z, et al. Search for cross-species transmission of porcine endogenous retrovirus in patients treated with living pig tissue. The XEN 111 Study Group. Science. 1999;285:1236–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5431.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fishman JA. Xenosis and xenotransplantation: current concepts and challenges (Abstract PL5:2) Xenotransplantation. 2005;12:370. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casey A. Historical review of corneal transplantation. A system of opthalmic operations. 1911:1013–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kissam R. Ceratoplastice in man. NY J Med Collat Sci. 1844;2:281–282. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wutzer Momoire sur la keratoplastie. Archives Generales De Medecine. 1844:1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Plouvier Keratoplastie. Gaz des Hop. 1845;21:386. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Power H. On transplantation of cornea. IV International Congress of Ophthalmology; London. 1872. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Hippel A. Eine neue Methode der Hornhauttransplantation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1888;34:108–130. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soomsawasdi B, Romayanonda N, Bhadrakom S. Hetero-keratoplasy using gibbon donor corneae. Asia Pac Acad Ophthalmol. 1964;2:251–261. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haq M. Fish cornea for grafting. Br Med J. 1972;2:712–713. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5815.712-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durrani KM, Kirmani TH, Hassan MM, et al. Penetrating keratoplasty with purified bovine collagen: report of a coordinated trial on fifteen human cases. Ann Ophthalmol. 1974;6:639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zirm E. Eine erfolgreiche totale keratoplastik (A successful total keratoplasty) Graefe Archiv für Ophthalmologie. 1906:580–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fanta H. Eduard Zirm (1863–1944) Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd. 1986;189:64–66. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1050756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zirm EK. Eine erfolgreiche totale Keratoplastik (A successful total keratoplasty). 1906. Refract Corneal Surg. 1989;5:258–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pan Z, Sun C, Jie Y, et al. WZS-pig is a potential donor alternative in corneal xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2007;14:603–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2007.00432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qian Y, Dana MR. Molecular mechanisms of immunity in corneal allotransplantation and xenotransplantation. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2001;3:1–21. doi: 10.1017/S1462399401003246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamagami S, Isobe M, Yamagami H, et al. Mechanism of concordant corneal xenograft rejection in mice: synergistic effects of anti-leukocyte function-associated antigen-1 monoclonal antibody and FK506. Transplantation. 1997;64:42–48. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199707150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Bedard E, Luo Y, et al. Animal models in xenotransplantation. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2000;9:2051–2068. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.9.2051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross JR, Howell DN, Sanfilippo FP. Characteristics of corneal xenograft rejection in a discordant species combination. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:2469–2476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larkin DF, Takano T, Standfield SD, et al. Experimental orthotopic corneal xenotransplantation in the rat. Mechanisms of graft rejection. Transplantation. 1995;60:491–497. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199509000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanaka K, Yamada J, Streilein JW. Xenoreactive CD4+ T cells and acute rejection of orthotopic guinea pig corneas in mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1827–1832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oh JY, Kim MK, Ko JH, et al. Histological differences in full-thickness vs. lamellar corneal pig-to-rabbit xenotransplantation. Vet Ophthalmol. 2009;12:78–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2008.00680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hargrave SL, Mayhew E, Hegde S, et al. Are corneal cells susceptible to antibody-mediated killing in corneal allograft rejection? Transpl Immunol. 2003;11:79–89. doi: 10.1016/S0966-3274(02)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hegde S, Mellon JK, Hargrave SL, et al. Effect of alloantibodies on corneal allograft survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1012–1018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bora NS, Gobleman CL, Atkinson JP, et al. Differential expression of the complement regulatory proteins in the human eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:3579–3584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mondino BJ, Ratajczak HV, Goldberg DB, et al. Alternate and classical pathway components of complement in the normal cornea. Arch Ophthalmol. 1980;98:346–349. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1980.01020030342023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galili U, Shohet SB, Kobrin E, et al. Man, apes, and Old World monkeys differ from other mammals in the expression of alpha-galactosyl epitopes on nucleated cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17755–17762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Good AH, Cooper DK, Malcolm AJ, et al. Identification of carbohydrate structures that bind human antiporcine antibodies: implications for discordant xenografting in humans. Transplant Proc. 1992;24:559–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooper DK. Depletion of natural antibodies in non-human primates--a step towards successful discordant xenografting in humans. Clin Transplant. 1992;6:178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper DK, Good AH, Koren E, et al. Identification of alpha-galactosyl and other carbohydrate epitopes that are bound by human anti-pig antibodies: relevance to discordant xenografting in man. Transpl Immunol. 1993;1:198–205. doi: 10.1016/0966-3274(93)90047-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oriol R, Ye Y, Koren E, et al. Carbohydrate antigens of pig tissues reacting with human natural antibodies as potential targets for hyperacute vascular rejection in pig-to-man organ xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 1993;56:1433–1442. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199312000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amano S, Shimomura N, Kaji Y, et al. Antigenicity of porcine cornea as xenograft. Curr Eye Res. 2003;26:313–318. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.26.5.313.15440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee HI, Kim MK, Oh JY, et al. Gal alpha(1–3)Gal expression of the cornea in vitro, in vivo and in xenotransplantation. Xenotransplantation. 2007;14:612–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2007.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hara H, Long C, Lin YJ, et al. In vitro investigation of pig cells for resistance to human antibody-mediated rejection. Transpl Int. 2008;21:1163–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holan V, Vitova A, Krulova M, et al. Susceptibility of corneal allografts and xenografts to antibody-mediated rejection. Immunol Lett. 2005;100:211–213. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cooper DK. Xenoantigens and xenoantibodies. Xenotransplantation. 1998;5:6–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.1998.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Phelps CJ, Koike C, Vaught TD, et al. Production of alpha 1,3-galactosyltransferase-deficient pigs. Science. 2003;299:411–414. doi: 10.1126/science.1078942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolber-Simonds D, Lai L, Watt SR, et al. Production of alpha-1,3-galactosyltransferase null pigs by means of nuclear transfer with fibroblasts bearing loss of heterozygosity mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7335–7340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307819101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hara H, Ezzelarab M, Rood PP, et al. Allosensitized humans are at no greater risk of humoral rejection of GT-KO pig organs than other humans. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:357–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bouhours D, Pourcel C, Bouhours JE. Simultaneous expression by porcine aorta endothelial cells of glycosphingolipids bearing the major epitope for human xenoreactive antibodies (Gal alpha 1–3Gal), blood group H determinant and N-glycolylneuraminic acid. Glycoconj J. 1996;13:947–953. doi: 10.1007/BF01053190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu A. Binding of human natural antibodies to nonalphaGal xenoantigens on porcine erythrocytes. Transplantation. 2000;69:2422–2428. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200006150-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Varki A. Loss of N-glycolylneuraminic acid in humans: Mechanisms, consequences, and implications for hominid evolution. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2001;(Suppl 33):54–69. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ezzelarab M, Ayares D, Cooper DK. Carbohydrates in xenotransplantation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2005;83:396–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim YG, Oh JY, Gil GC, et al. Identification of alpha-Gal and non-Gal epitopes in pig corneal endothelial cells and keratocytes by using mass spectrometry. Curr Eye Res. 2009;34:877–895. doi: 10.3109/02713680903184243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams KA, Coster DJ. The immunobiology of corneal transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84:806–813. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000285489.91595.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Higuchi R, Streilein JW. CD8+ T cell-mediated delayed rejection of orthotopic guinea pig cornea grafts in mice deficient in CD4+ T cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:175–182. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanaka K, Sonoda K, Streilein JW. Acute rejection of orthotopic corneal xenografts in mice depends on CD4(+) T cells and self-antigen-presenting cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:2878–2884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Y, Hamrah P, Zhang Q, et al. Draining lymph nodes of corneal transplant hosts exhibit evidence for donor major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-positive dendritic cells derived from MHC class II-negative grafts. J Exp Med. 2002;195:259–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.20010838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huq S, Liu Y, Benichou G, et al. Relevance of the direct pathway of sensitization in corneal transplantation is dictated by the graft bed microenvironment. J Immunol. 2004;173:4464–4469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.7.4464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rogers NJ, Jackson IM, Jordan WJ, et al. Cross-species costimulation: relative contributions of CD80, CD86, and CD40. Transplantation. 2003;75:2068–2076. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000069100.67646.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Torres PF, De Vos AF, van der Gaag R, et al. Cytokine mRNA expression during experimental corneal allograft rejection. Exp Eye Res. 1996;63:453–461. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.King WJ, Comer RM, Hudde T, et al. Cytokine and chemokine expression kinetics after corneal transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;70:1225–1233. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200010270-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pindjakova J, Vitova A, Krulova M, et al. Corneal rat-to-mouse xenotransplantation and the effects of anti-CD4 or anti-CD8 treatment on cytokine and nitric oxide production. Transpl Int. 2005;18:854–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Strestikova P, Plskova J, Filipec M, et al. FK 506 and aminoguanidine suppress iNOS induction in orthotopic corneal allografts and prolong graft survival in mice. Nitric Oxide. 2003;9:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Slegers TP, Torres PF, Broersma L, et al. Effect of macrophage depletion on immune effector mechanisms during corneal allograft rejection in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2239–2247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Streilein JW. Ocular immune privilege: therapeutic opportunities from an experiment of nature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:879–889. doi: 10.1038/nri1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Niederkorn JY. The immune privilege of corneal grafts. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;74:167–171. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1102543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, et al. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yang W, Li H, Chen PW, et al. PD-L1 expression on human ocular cells and its possible role in regulating immune-mediated ocular inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:273–280. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Niederkorn JY. Immune mechanisms of corneal allograft rejection. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:1005–1016. doi: 10.1080/02713680701767884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mondino BJ, Sumner H. Complement inhibitors in normal cornea and aqueous humor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984;25:483–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chandler JW, Leder R, Kaufman HE, et al. Quantitative determinations of complement components and immunoglobulins in tears and aqueous humor. Invest Ophthalmol. 1974;13:151–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cozzi E, White DJ. The generation of transgenic pigs as potential organ donors for humans. Nat Med. 1995;1:964–966. doi: 10.1038/nm0995-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Adams DH, Kadner A, Chen RH, et al. Human membrane cofactor protein (MCP, CD 46) protects transgenic pig hearts from hyperacute rejection in primates. Xenotransplantation. 2001;8:36–40. doi: 10.1046/j.0908-665x.2000.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Diamond LE, Quinn CM, Martin MJ, et al. A human CD46 transgenic pig model system for the study of discordant xenotransplantation. Transplantation. 2001;71:132–142. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200101150-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Loveland BE, Milland J, Kyriakou P, et al. Characterization of a CD46 transgenic pig and protection of transgenic kidneys against hyperacute rejection in non-immunosuppressed baboons. Xenotransplantation. 2004;11:171–183. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-3089.2003.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ekser B, Long C, Echeverri GJ, et al. Impact of Thrombocytopenia on Survival of Baboons with Genetically Modified Pig Liver Transplants: Clinical Relevance. Am J Transplant. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Polejaeva IA, Chen SH, Vaught TD, et al. Cloned pigs produced by nuclear transfer from adult somatic cells. Nature. 2000;407:86–90. doi: 10.1038/35024082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rood PP, Hara H, Busch JL, et al. Incidence and cytotoxicity of antibodies in cynomolgus monkeys directed to nonGal antigens, and their relevance for experimental models. Transpl Int. 2006;19:158–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ezzelarab M, Hara H, Busch J, et al. Antibodies directed to pig non-Gal antigens in naive and sensitized baboons. Xenotransplantation. 2006;13:400–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2006.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen G, Qian H, Starzl T, et al. Acute rejection is associated with antibodies to non-Gal antigens in baboons using Gal-knockout pig kidneys. Nat Med. 2005;11:1295–1298. doi: 10.1038/nm1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen G, Sun H, Yang H, et al. The role of anti-non-Gal antibodies in the development of acute humoral xenograft rejection of hDAF transgenic porcine kidneys in baboons receiving anti-Gal antibody neutralization therapy. Transplantation. 2006;81:273–283. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000188138.53502.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Phelps CJ, Ball SF, Vaught TD, et al. Production and characterization of transgenic pigs expressing porcine CTLA4-Ig. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:477–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Petersen B, Ramackers W, Tiede A, et al. Pigs transgenic for human thrombomodulin have elevated production of activated protein C. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:486–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wuensch A, Klymiuk N, Kurome M, et al. Site-specific expression of human thrombomodulin on porcine endothelium. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:375. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oropeza M, Petersen B, Carnwath JW, et al. Transgenic expression of the human A20 gene in cloned pigs provides protection against apoptotic and inflammatory stimuli. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:522–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3089.2009.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Petersen B, Ramackers W, Lucas-Hahn A, et al. Production and characterization of pigs transgenic for human hemoxygenase-I by somatic nuclear transfer. Xenotransplantation. 2008;15:301. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Petersen B, Lucas-Hahn A, Lemme E, et al. Generation and characterization of human hemoxygenase-1 (hHO-1) transgenic pigs. Xenotransplantation. 2009;16:373–374. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nyquist GW. Rheology of the cornea: experimental techniques and results. Exp Eye Res. 1968;7:183–188. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(68)80064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kampmeier J, Radt B, Birngruber R, et al. Thermal and biomechanical parameters of porcine cornea. Cornea. 2000;19:355–363. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200005000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Anderson K, El-Sheikh A, Newson T. Application of structural analysis to the mechanical behaviour of the cornea. J R Soc Interface. 2004;1:3–15. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2004.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kennedy EA, Voorhies KD, Herring IP, et al. Prediction of severe eye injuries in automobile accidents: static and dynamic rupture pressure of the eye. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2004;48:165–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lombardo M, De Santo MP, Lombardo G, et al. Atomic force microscopy analysis of normal and photoablated porcine corneas. J Biomech. 2006;39:2719–2724. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Endo K, Nakamura T, Kawasaki S, et al. Porcine corneal epithelial cells consist of high- and low-integrin beta1-expressing populations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3951–3954. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lange W, Debbage PL, Basting C, et al. Neoglycoprotein binding distinguishes distinct zones in the epithelia of the porcine eye. J Anat. 1989;166:243–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sweatt AJ, Ford JG, Davis RM. Wound healing following anterior keratectomy and lamellar keratoplasty in the pig. J Refract Surg. 1999;15:636–647. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19991101-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Oh JY, Kim MK, Lee HJ, et al. Comparative observation of freeze-thaw-induced damage in pig, rabbit, and human corneal stroma. Vet Ophthalmol. 2009;12 (Suppl 1):50–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-5224.2009.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zeng Y, Yang J, Huang K, et al. A comparison of biomechanical properties between human and porcine cornea. J Biomech. 2001;34:533–537. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ahearne M, Yang Y, Then KY, et al. An indentation technique to characterize the mechanical and viscoelastic properties of human and porcine corneas. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35:1608–1616. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9323-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Elsheikh A, Alhasso D, Rama P. Biomechanical properties of human and porcine corneas. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86:783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Elsheikh A, Wang D, Brown M, et al. Assessment of corneal biomechanical properties and their variation with age. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32:11–19. doi: 10.1080/02713680601077145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Binder PS, Abel R, Jr, Polack FM, et al. Keratoplasty wound separations. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:109–115. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90880-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Obata H, Tsuru T. Corneal wound healing from the perspective of keratoplasty specimens with special reference to the function of the Bowman layer and Descemet membrane. Cornea. 2007;26:S82–89. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31812f6f1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]