Abstract

Objective:

To compare and evaluate the price and quality of “branded” and branded-generic equivalents of some commonly used medicines manufactured by the same pharmaceutical company in India.

Materials and Methods:

Five commonly used medicines: alprazolam, cetirizine, ciprofloxacin, fluoxetine, and lansoprazole manufactured in branded and branded-generic versions by the same company were selected. Price-to-patient and price-to-retailers were found for five “pair” of medicines. Both quantitative and qualitative analysis were performed following the methods prescribed in the Indian Pharmacopoeia 2007 on five pair of medicines. The tests performed were identification test, chemical composition estimation test, uniformity of contents test, uniformity of weight, and dissolution studies.

Main Outcome Measures:

Price-to-patient, retailer mark-up and qualitative analysis of branded and branded-generic medicines.

Results:

Retailer margin for five branded medicines were in the range of 25-30% but for their branded-generics version manufactured by the same company it was in the range of 201-1016%. Price-to-patient for the branded version of cetirizine, fluoxetine, ciprofloxacin, lansoprazole, and alprozolam was higher by 41%, 33%, 0%, 14%, and 31% than branded-generic. Both versions of five medicines were within their permissible range for all the quantitative and qualitative parameters as prescribed in Indian Pharmacopoeia.

Conclusion:

Difference in price-to-patient was not as huge as it is expected for generics but margins for retailer were very high for branded-generics. Quality of branded-generics is same as for their branded version. The study highlights the need to modify the drug price policy, regulate the mark-ups in generic supply chain, conduct and widely publicize the quality testing of generics for awareness of all stakeholders.

Keywords: Branded medicines, branded-generic, generics, mark-ups, medicine price, India, quality testing

Introduction

The use of generic drugs is steadily increasing internationally as a result of economic pressure on drug budgets. Generic drugs provide the opportunity for major savings in healthcare expenditure since they are usually substantially lower in price than the innovator brands.[1]However, physicians are apprehensive regarding the quality of generic drugs[2,3]and have concerns about their reliability as well as interchange of certain drug categories.[4]Although the generic medicines are bio-equivalents of their innovator counterparts and are produced in similar facilities according to good manufacturing practices,[5]these are widely believed as inferior in their therapeutic efficacy and quality to branded products.[6,7]Marketing practices adopted by manufacturers of imported branded medicines also propagate the belief that generics are of inferior quality as reported from countries in Central and Eastern Europe and independent countries emerged from former Soviet Union.[8]The present study was conducted to compare the quality and price of generic (branded-generic) drug products to their expensive popular brand (branded) products manufactured by the same pharmaceutical company in India.

Currently, almost all medicines in India are sold under a brand (trade) name and medicines are called as branded medicines or branded-generic. In real sense, Indian market does not have branded medicines (a name commonly given to an innovator product) because till January 2005 product patent was not applicable in India. In India, many pharmaceutical companies manufacture two types of products for the same molecule, i.e. the branded product which they advertise and push through doctors and branded-generic which they expect retailers to push in the market. The so-called branded medicines in India are manufactured and promoted by multinationals or by reputed Indian manufacturers. branded-generics, on the other hand, are not promoted or advertized by the manufacturer. This category closely resembles formulations referred to as ‘generics’ worldwide. Patients’ and doctors’ perception for all branded-generics irrespective of company is the same.

In India, generic substitution is legally not allowed so patients’ awareness about generics is limited and doctors and patients do not want pharmacist to change the trade name written by doctor. Hence, consumer awareness for the generics, variety of trade names available in the market, and price variation is very limited. Hence, there is need to conduct a study that can document the price structure and quality of the branded product and their branded-generic versions manufactured in India.

A “pair” of product from the same company was chosen to appreciate the price structure and mark-ups for the two versions.

Methods

Quality and price of medicines were studied to evaluate the two versions of the same therapeutic molecule. Data were collected during September to November 2008.

Selection of medicines

Five commonly used medicines from different classes were selected whose branded (popular brand) and branded-generic versions were manufactured by the same pharmaceutical company. The five medicines chosen were alprazolam, (0.25 mg), cetirizine (10 mg), ciprofloxacin (500 mg), fluoxetine (20 mg), and lansoprazole (30 mg).

Medicine price

Price-to-patient and price-to-retailer (PTR) were analyzed. Maximum retail price (MRP) is the price-to-patient and is always printed on the package in India. Medicines are available to patient at the MRP mentioned on the package of medicine. Details of the five "paired" drug products sold under different trade names with their MRP were checked physically with the private retail pharmacies (chemist shop).

PTR is the price at which wholesaler (distributor) sells the product to the retailer and the bill (voucher) given to retailer by wholesaler mentions the PTR. PTR for all medicines was found by looking at the vouchers. This price was checked and confirmed from Form V (under DPCO, 1995) available at the distributors of the company. It is mandatory for all the companies to give Form V that gives details of the product with MRP, PTR, taxes paid, etc to their distributors.

Quality testing

The test samples were procured from the licensed authorized chemist dealers through valid purchase invoice. The sample size comprised 10×10 tablets/capsules of both branded and branded-generic versions of each drug product. Efforts were made to procure these test samples (pairs) with identical date of manufacture to rule out the possibility of difference in assay because of different dates of manufacturing. The qualitative as well as quantitative analysis was carried out in a Government-approved laboratory following the methods prescribed in the Indian Pharmacopoeia, (2007) as per the standards laid down in the Drugs and Cosmetics Act 1940 and Rules 1945.[9]

Following tests were performed.

Identification test: Identity of the drug molecule was established by performing the identification test through instrumental analysis using HPLC (high pressure liquid chromatography) or IR (infra-red spectroscopy) as per method prescribed for each medicine.

Chemical composition test\: The samples were subjected to quantitative analysis using HPLC instrumental analytical methods as provided in Indian Pharmacopoeia 2007.

Uniformity of content test: To confirm the uniformity of contents in the batch, the sampled dosage units were subjected to “uniformity of contents” test wherein assay on 10 units of dosage form were performed individually using instrumental analytical methods. The test for uniformity of content is not applicable to tablets/capsules containing more than 10 mg; it was conducted only for alprazolam (0.25 mg) and cetirizine (10 mg).

Uniformity of weight: All 10 units of sample were tested for uniformity of weight as prescribed.

Tests for Dissolution: The samples were subjected to dissolution studies to evaluate their drug release pattern. These studies were performed in the dissolution media specified in the individual monograph of the Indian Pharmacopoeia 2007 on six dosage units and were indicative of the in vivo availability of active drug moiety from the dosage form, i.e. tablet or capsule.

Results

Comparative Price and Mark-Up for Branded and Branded Generic Pair of Medicines

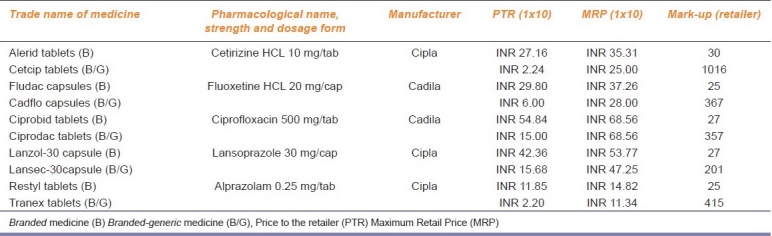

Details of five “pairs” of medicines including their trade name as sold in the Indian market, strength, dosage form, and the pharmaceutical company that manufactures these products are given in Table 1. Price-to-patient (MRP) and price-to-retailer (PTR) found for all the five ‘pair’ of medicines is tabulated in Table 1. PTR for the branded product of cetirizine was 11 times the price for branded-generic by the same company. Retailer is earning INR 22.76 for 10 tablets of branded-generic cetirizine versus Rs 8.16 for the branded version from the same company. For ciprofloxacin, the MRP of both the branded and branded-generic product was same but the branded-generic was available to retailer at 3.6 times less price than branded medicine from the same company.

Table 1.

Comparative price structure of Branded and Branded-generic medicines

The price-to-patient (MRP) of the branded product for the five medicines evaluated was 41%, 33%, 0%, 14%, and 31% higher than the MRP of the branded-generic version of the same company. On the other hand, PTR for branded-generic was 1112%, 397%, 266%, 170%, and 439% less than the branded version of cetirizine, fluoxetine, ciprofloxacin, lansoprazole, and alprazolam, respectively. Retailer mark-ups for five “pair” of medicines for branded versus branded-generic: cetirizine, fluoxetine, ciprofloxacin, lansoprazole, and alprazolam were 30% versus 1016%, 25% versus 367%, 25% versus 357%, 27% versus 201%, and 25% versus 415%, respectively [Table 1].

Quality of Branded and Branded Generic Pair of Medicines

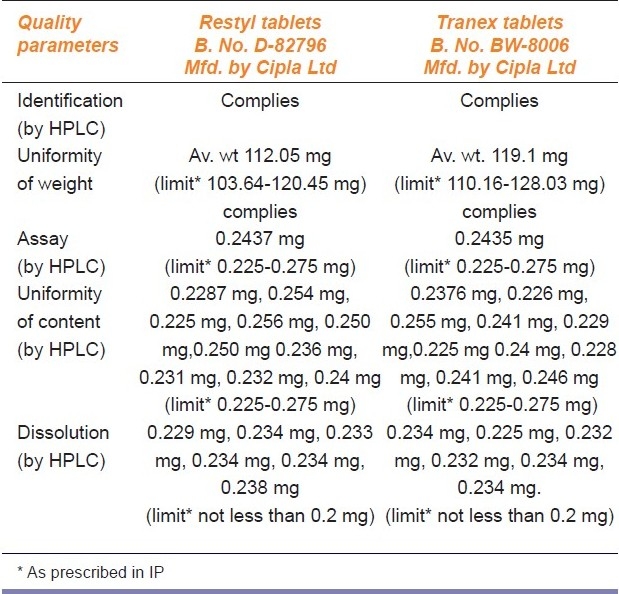

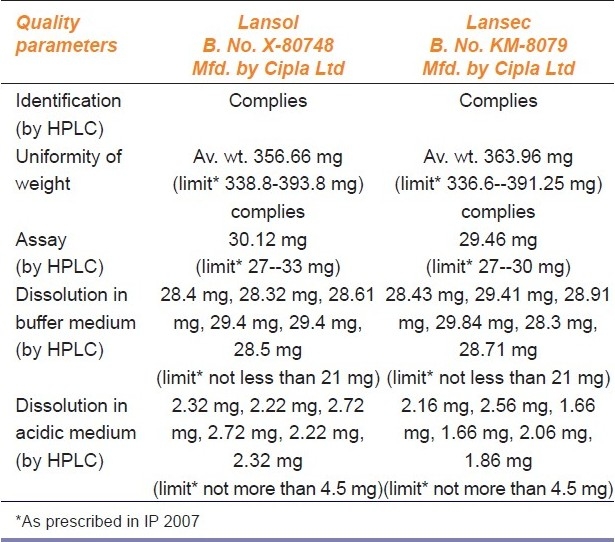

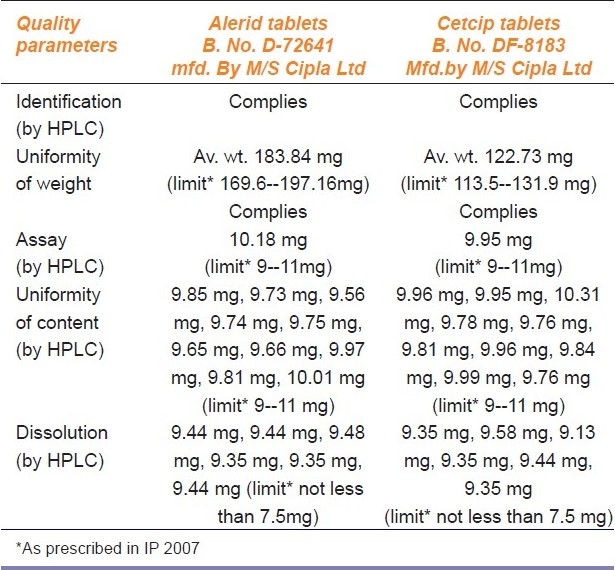

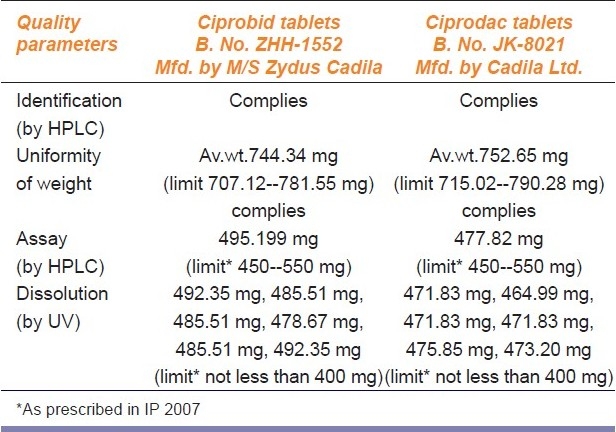

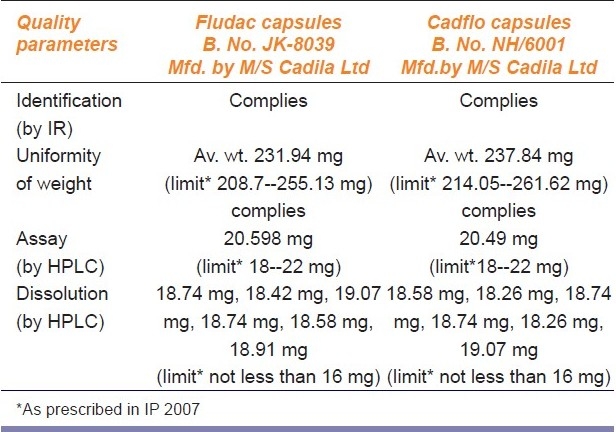

Identification test: All the five “paired” medicines of branded and branded-generics gave positive identification tests when tested on HPLC or IR establishing their chemical identity [Tables 2–6].

Chemical composition test: The quantitative analysis conducted using the HPLC method showed each unit of the tested samples to be well within the prescribed range [Tables 2–6].

Uniformity of content: This test was done for alprazolam and cetirizine and results for both the versions of medicines were within the prescribed range [Tables 2 and 3].

Uniformity of weight: Each unit of the sample was within the prescribed range for all the five “pair” of medicines [Tables 2–6]

Dissolution test: The dissolution test for all the five “paired” medicines were within the permissible limits of the statutory standards [Tables 2–6].

Table 2.

Comparative analytical evaluation of branded and branded-generic drug product Alprazolam tablets (0.25 mg)

Table 6.

Comparative analytical evaluation of branded / branded-generic drug product Lansoprazole capsules (30 mg)

Table 3.

Comparative analytical evaluation of branded and branded generic drug product Cetirizine tablets (10 mg)

Table 4.

Comparative analytical evaluation of branded and brandedgeneric drug product Ciprofloxacin tablets (500 mg)

Table 5.

Comparative analytical evaluation of branded and brandedgeneric drug product Fluoxetine capsules (20 mg)

Discussion

This is one of the first studies in India conducted to systematic evaluate the price-to-patient and retailer mark-up for the branded and branded-generic versions of the same therapeutic molecule manufactured by the same company. This study has also evaluated the quality of the two versions. Findings of the study revealed that there are huge mark-ups for retailer on branded-generic medicines. The retailer margin for five branded medicines studied was in the range of 25-30%, but for their branded-generics version manufactured by the same company it was in the range of 201-1016%. Both versions of all five medicines cleared all the quantitative and qualitative parameters as prescribed in Indian Pharmacopoeia, 2007. There exists a widespread belief among people and dispensing chemists that a branded product is better in terms of quality and safety than the generic.[10–12]A systematic review has shown that generic and brand name cardio-vascular drugs were similar for nearly all clinical outcomes. This study concluded that there is no evidence of superiority of brand preparations to generic drugs.[13]Such studies may be helpful in promoting generic drug use that reduces unnecessary spending without improving clinical outcome. In most developed countries, generic medicines are promoted by competition-enhancing policies operating through health-care reimbursements to contain expenditure and encourage efficient use of resources.[14]

Results of our study revealed that price-to-patient for the branded-generic version was not much less than to its branded counterpart; branded-generic was available at 70-100% cost of the branded product. In India, medicine prices are set in one of the two ways. Medicine prices are under the purview of Department of Pharmaceuticals which itself is under ministry of chemicals and fertilizers. The Drug Price Control Order (DPCO) identifies active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) for which a pricing formula is used to set the MRP. There are only 74 bulk drugs which are under price control[15]and are called scheduled medicines. For all other medicines---called “non-scheduled medicines”---the manufacturer sets the price and registers that price with the National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA) under Department of Pharmaceuticals.[16]The medicines are sold at the printed MRP on their label and dispensing pharmacist cannot charge a price exceeding MRP printed on the pack, as per the provisions under paragraph 16 of the DPCO, 1995. For scheduled medicines, the NPPA pricing formula sets the 8% mark-up for wholesalers and 16% for retailers. For non-scheduled medicines, these markups are not set, but it is agreed by the partners of the trade that for branded medicines average mark-up would be around 10% and 20% for wholesalers and retailers, respectively.

In our sample of medicines, only ciprofloxacin is under price control and other four belong to non-schedule medicine. The study revealed that even for the branded version of both schedule and non-scheduled medicines, the retailer margin was more than the established margin, it was in the range of 25-30%. For the branded-generic version, the retailer margins were very large, 201-1016%. Pharmaceutical companies decide not only the final price (MRP) to the patient but also the mark-up for the retailer. If the marketing is done by the company as for the "branded" version then the major mark-ups are for the company; if the marketing and promotion are done by the retailer as in the case of branded-generic then the PTR is less, but MRP is not much different. Therefore, the branded-generics are promoted by the retailers for monetary considerations in total disregard to the patient's interests. The ultimate consumer, i.e. patient is not benefited much by preferring branded-generic versions to its branded version. A newspaper reports the huge profit margins for retailers ranging from 500% to1000% on generic medicines in India.[17]The high mark-ups on generics are totally negating the very concept of affordable generic medicines for patients.

Unlike developed countries, people in developing countries pay the cost of medicines out-of-pocket. In India, more than 80% health financing is borne by patients.[18]India is known to export medicines to various countries at low cost, but faces the challenge of access to affordable and quality medicines for its own population.[19]Hence, the government should have a policy whereby the prices of branded-generic drugs can be made realistic and affordable to common man. We need to have legislation to that effect. The profit margins presently being shared by traders must be passed to consumer.

In India, a dispensing pharmacist is not authorized to substitute a branded medicine with a branded-generic (or generic) as per the provisions under Rule 65 of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 and Rules, 1945, which also add to the patient's burden. In the USA substitution is allowed and patients accept generic substitution if physician approves of the same. Generic substitution rates have increased remarkably there, probably due to greater acceptance by physicians and pharmacists as well as encouragement from the third party payers.[20]Cheaper generics are one of the important factors to reduce health-care cost. The practice of generic substitution is strongly supported by health authorities in many developed countries.[21]Use of generic drugs, which are bio-equivalent to brand name drug, can help contain prescription drug spending.[22]Government of India has opened few generic drug stores in some states that sell generic medicines manufactured by public sector companies.[23]The quality of generic medicines available on these stores at cheaper rates should be tested and compared with popular brands and results should be widely published. Studies involving comparative evaluation on quality of branded and their generic counterpart may be made mandatory for the generic (or branded-generic) manufacturer and their reports should be made public to promote generic use and prescriptions.

One inherent limitation of this study is that we have tested pair of branded and branded-generic medicines that were manufactured by the same “reputed” company. Though it is expected that both the versions should have the same quality but perception for any branded-generic is same among doctors and patients. So to start with, we have taken both branded and branded-generic products of the same company and studied not only the quality but also the price structure.

Conclusions

Findings of the present study indicate that both the branded and branded-generic versions of the five “paired” medicines had identical quality and they fulfilled all the criteria prescribed by the statutory standards. Hence, the general notion and doubt regarding the quality of the branded-generic version of medicines needs to be erased conducting more such studies and publishing them widely.Suitable changes in the drug price policy may be made to have lower prices for branded-generic versions. Transparency in fixing the MRP by the manufacturer and clear guidelines for mark-ups at least for branded-generics is required in pharmaceutical trade. The government must take up generic promotional schemes, general awareness programs on quality of generics to build confidence among prescribers, pharmacists, and consumers. Availability of generics or branded-generics in the market with lower price tag and assured quality is essential to make the medicines affordable.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the cooperation of retail pharmacists and distributors who helped us in collection of the data.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.King DR, Kanavos P. Encouraging the use of generic medicines: Implications for transition economies. Croat Med J. 2002;43:462–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilyard MW, Dovey SM, Rosentstreich D. General practitioners’ views on generic medication and substitution. N Z Med J. 1990;103:318–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas R, Chatterjee P, Mundle M. Prescribing habits of physicians in medical college, Calcutta. Indian J Community Med. 2000;25:161–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Awaisu A, Ibrahim MI, Ping CC, Jamshed S. Physicians’ views on generic medicines: A narrative review. J Generic Med. 2010;7:30–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davit BM, Nwakama PE, Buehler GJ, Conner DP, Haidar SH, Patel DT, et al. Comparing generic and innovator drugs: A review of 12 years of bioequivalence Data from the United States Food and Drug Administration Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1583–97. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shrank WH, Cox ER, Fischer MA, Mehta J, Choudhry NK. Patients’ perceptions of generic medications. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:546–56. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassali A, Stewart K. Quality use of generic medicines. Aust Prescr. 2004;27:80–1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joncheere KD, Paal T. Providing affordable medicines in transitional countries. In: Dukes MN, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Joncheere CP, Rietveld AH, editors. Drugs and money: Prices, affordability and cost containment. Amsterdam (Netherlands): ISO Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malik V. 19th ed. Lucknow (India): Eastern Book Company; [last accessed on 2010 Jun 13]. Laws relating to Drugs and Cosmetics. Available from: http://webstore.ebc-india.com/product_info.php?products_id=874. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shafie AA, Hassali MA. Price comparison between innovator and generic medicines sold by community pharmacies in the state of Penang, Malaysia. J Gen Med. 2008;6:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figueiras MJ, Marcelino D, Cortes MA. People's views on the level of agreement of generic medicines for different illnesses. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:590–4. doi: 10.1007/s11096-008-9247-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjoenniksen I, Morten Lindbaek M, Granas AG. Patients’ attitudes towards and experiences of generic drug substitution in Norway. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28:284–9. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, Stedman MR, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand name drugs used in cardio-vascular diseases. JAMA. 2008;300:2514–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanavos P, Costa-Font J, Seeley E. Competition in off-patent drug markets: Issues, regulation and evidence. Economic Policy. 2008;23:499–544. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drugs (Price Control) Order, 1995, Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers, Department of chemicals and petrochemicals, Government of India. 1995. [last accessed on 2010 Jun 1]. Available from: http://www.nppaindia.nic.in/drug_price95/txt1.html .

- 16.Department of Pharmaceuticals, Government of India. NPPA. [last accessed on 2010 Jun 9]. Available from: http://pharmaceuticals.gov.in/

- 17.Sood R. Generic drug companies fleecing patients. The Tribune, Chandigarh, India, Himachal Plus. 2010. Feb 9, [last accessed on 2010 Jun 13]. Available from: http://www.tribuneindia.com/2010/20100210/himplus.htm#1.

- 18.Creese A, Kotwani A, Kutzin J, Pillay A. Evauating pharmaceuticals for health policy in low and middle income country settings. In: Freemantle N, Hill S, editors. Evaluating pharmaceuticals for health policy and reimbursement. Massachusetts USA: Blackwell Publication; 2004. pp. 227–43. (in collaboration with WHO Geneva) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotwani A, Ewen M, Dey D, Iyer S, Lakshmi PK, Patel A, et al. Medicine prices and availability of common medicines at six sites in India: Using a standard methodology. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:645–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dong-Churl S. Trends of generic substitution in community pharmacies. Pharm World Sci. 1999;21:260–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1008781619011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smeaton J. The generics market. Aust J Pharm. 2000;81:540–2. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nightingale SL. From the Food and Drug Administration. JAMA. 1998;279:645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotwani A. Will generic drug stores improve access to essential medicines for the poor in India? J Public Health Policy. 2010;31:178–84. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]