Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the antiobesity effects of the ethanolic extract of Argyreia speciosa roots in rats fed with a cafeteria diet (CD).

Materials and Methods:

Obesity was induced in albino rats by feeding them a CD daily for 42 days, in addition to a normal diet. Body weight and food intake was measured initially and then every week thereafter. On day 42, the serum biochemical parameters were estimated and the animals were sacrificed with an overdose of ether. The, liver and parametrial adipose tissues were removed and weighed immediately. The liver triglyceride content was estimated. The influence of the extract on the pancreatic lipase activity was also determined by measuring the rate of release of oleic acid from triolein.

Results:

The body weight at two-to-six weeks and the final parametrial adipose tissue weights were significantly lowered (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively) in rats fed with the CD with Argyreia speciosa extract 500 mg/kg/day as compared to the CD alone. The extract also significantly reduced (P < 0.01) the serum contents of leptin, total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDL), and triglycerides, which were elevated in rats fed with CD alone. In addition, the extract inhibited the induction of fatty liver with the accumulation of hepatic triglycerides. The extract also showed inhibition of pancreatic lipase activity by using triolein as a substrate.

Conclusions:

The ethanolic extract of Argyreia speciosa roots produces inhibitory effects on cafeteria diet-induced obesity in rats.

Keywords: Antiobesity, Argyreia speciosa, Cafeteria diet

Introduction

Obesity is a medical condition involving an excess accumulation of body fat. The prevalence of obesity is increasing not only in adults, but also among children and adolescents. The prevalence of obesity has increased steadily over the past five decades, and may have a significant impact on the quality adjusted life years.[1]

The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3) conducted in 2005 – 2006 indicates that obesity has increased significantly in India, particularly among women, and needs the attention of the people concerned. It was found that 51% of the 1, 11, 781 women tested, of age 15 – 49 years, were obese . The percentage prevalence of obesity among Indians is still less in comparison with the global context, but being the second-most populated country in the world, urgent attention is required toward this issue; otherwise, India would be one of the first nations, from the developing countries in Asia, to be put on the obesity map.[2]

At present only two drugs, sibutramine and orlistat have been approved for long-term use in the treatment of obesity. Each of these promotes 5 to 10% loss of body weight and has their own limitations and side effects. An endocannibinoid receptor antagonist, rimonabant was withdrawn from the market due to concerns about its safety, including risk of seizures and suicidal tendencies.[3] These currently licensed drugs are best, when used in conjunction with diet, exercise, and behavior change regimens. However, they do not cure obesity; weight rebounds when discontinued. Thus, there is a great demand for the search of new and safer antiobesity medicines.

Plants have formed the basis for traditional medicine systems. Numerous preclinical and clinical studies, with various herbal medicines reported significant improvement in controlling body weight, without any noticeable adverse effects.

Argyreia speciosa (Syn: Argyreia nervosa) belonging to family Convolulaceae is a woody climbing shrub found throughout India. It has been used as a Rasayana drug in the traditional Ayurvedic system of medicine.[4] The roots of this plant are used in wounds, ulcers, dyspepsia, cough, hemorrhoids, obesity, anemia, diabetes, and arthritis.[5] It has been reported to possess immunomodulatory,[6] hepatoprotective,[7] antioxidant, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory properties.[8] However, its antiobesity profile has not been documented. Hence, the objective of the present study is to investigate the effect of the ethanolic extract of Argyreia speciosa roots on cafeteria diet-induced obese rats. In addition, the possible mechanism of antiobese action of the extract was investigated by measuring its influence on serum leptin levels and pancreatic lipase activity. Sibutramine was used as the reference standard drug.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Argyreia speciosa extract (ASE)

The roots of Argyreia speciosa were collected from the fields surrounding Belgaum and were identified by the Head of the Department of Botany, Shivaji University, Kolhapur, Maharashtra, India, where a voucher specimen has been deposited. The roots were air dried, powdered, and then extracted with 70% ethanol by using the soxhlet method. The extract was filtered with Whatman No. 1 filter paper and then the solvent evaporated at a reduced pressure by using the Rotavapor apparatus to get a viscous mass, which was then stored at 40 C until used. The yield of the extract obtained was 4.2%.

Phytochemical study

The fresh ASE was subjected to standard phytochemical screening tests for various phytoconstituents.

Acute toxicity studies

The acute toxicity test of ASE was determined as per the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OECD) guidelines No. 420. Female Wistar rats (150 – 200 g) were used for this study. The initial dose of 2000 mg/kg p.o. of the ASE was selected and administered to a group of five animals. The treated animals were monitored for 14 days, for mortality and general behavior. No toxic symptoms or mortality was observed till the end of the study. The lethal dose (LD50) selected was 2 g/kg body weight. Hence, the experimental dose was selected as one-fourth (500 mg/kg) of the LD50 dose.

Experimental animals

Albino Wistar rats (180 – 200 g) were obtained from the Central Animal House, J.N. Medical College, Belgaum, and housed in a group of six animals, for one week, in a 12:12 hour light and dark cycle, in a temperature and humidity controlled room. The animals were given free access to food and water. After the one-week adaptation period, the healthy animals were used for the study. The Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, KLE University, Belgaum approved the experimental protocol.

Composition of Cafeteria diet

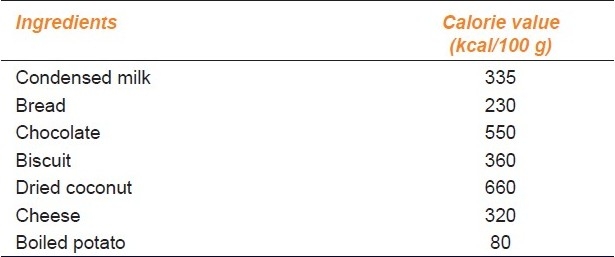

The CD consisted of three diets — (a) Condensed Milk (8 g) + Bread (8 g). (b) Chocolate (3 g) + Biscuits (6 g) + Dried Coconut (6 g), and (c) Cheese (8 g) + Boiled Potato (10 g). The three diets were presented to the individual rats on days one, two, and three, respectively, and then repeated for 42 days in the same succession.[9] The calorie value of the CD is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition and calorie value of the cafeteria diet

Treatment protocol

The animals were divided into five groups of six animals each and individually housed in cages. The normal control group continued to be fed a laboratory pellet chow ad libitum (calorie value = 280 kcal/100 g). The cafeteria diet-control group received the CD in addition to the normal diet. The remaining two groups were fed with the CD along with the normal diet and received sibutramine (2 mg/kg/day i.p.) and ASE as a suspension in Tween 80 (500 mg/kg/day p.o.), respectively. The treatment was continued for six weeks. The animals were weighed at the start of the experiment and then every week thereafter.

Measurement of food intake

The food intake of each animal was determined initially and then every week thereafter by measuring the difference between the preweighed chows and the weight of the food that remained after 24 hours, and the results were expressed as a mean energy intake for a group of six rats in kcal/week.

Blood Biochemical Analysis

On day 42, blood was collected by retro-orbital puncture from the ether-anesthetized rats and subjected to centrifugation to obtain the serum. The serum levels of glucose, total-cholesterol, high density protein (HDL), LDL, and triglycerides (TGs) were estimated using the biochemical kits (Beacon Diagnostics). The atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) was calculated by using: AIP = log (TGs / HDL). The concentration of leptin in the serum was measured with the rat leptin Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kit (USCN life sciences Inc., Wuhan).

Estimation of Liver weight, Parametrial adipose tissue weight, and Liver triglyceride content

The animals were sacrificed with an overdose of diethyl ether. The livers and parametrial adipose tissues were quickly removed and weighed. The liver tissues were stored at –80°C until an analysis was performed. The liver triglyceride content was estimated as follows; a portion (0.5 g) of liver tissue was homogenized in the Krebs Ringer Phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 4.5 ml), and the homogenate (0.2 ml) was extracted with a chloroform-methanol mixture (2:1, v/v, 4 ml). The extract was concentrated and the residue was analyzed using a Triglyceride E-test kit.

Measurement of Pancreatic lipase activity

The lipase activity was determined by measuring the rate of release of oleic acid from triolein. A suspension of triolein (80 mg), phosphatidylcholine (10 mg), and taurocholic acid (5 mg) in 9 ml of 0.1 M N-Tris (hydroxymethyl) methyl-2-aminoethanesulfonic acid (TES) buffer (pH 7.0), containing 0.1 M NaCl, was sonicated for 5 minutes. This sonicated substrate suspension (0.1 ml) was incubated with 0.05 ml (final concentration 5 units per tube) of pancreatic lipase and 0.1 ml of various concentrations (250, 500, 1000, and 2000 mg/ml) of ASE for 30 minutes at 370 C, in a final volume of 0.25 ml, and the released oleic acid was measured by the Belfrage and Vaughan method.[10] The lipase activity was expressed as moles of oleic acid released per milliliter of reaction mixture per hour.

Statistical Analysis

The results were expressed as mean ± standard error (SEM). The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Phytochemical test

Phytochemical screening revealed the presence of saponin glycosides, sterols, flavonoids, tannins, and phenolic compounds in ASE.

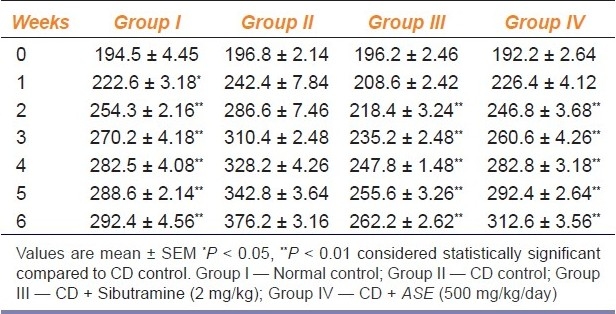

Effect of ASE on Body weight

Table 2 shows the changes in body weight in the different group of animals, during the experiment. Consumption of CD for six weeks produced a significant (P < 0.01) increase in body weight compared to the consumption of normal pellet chow (normal control group). Treatment with ASE at a dose of 500 mg/kg significantly (P < 0.01) reduced the increase in body weight as compared to the CD control group. However, treatment with sibutramine also reduced the increase in body weight, significantly (P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Effect of Argyreia speciosa root extract on body weight (g) in rats fed with cafeteria diet (n = 6)

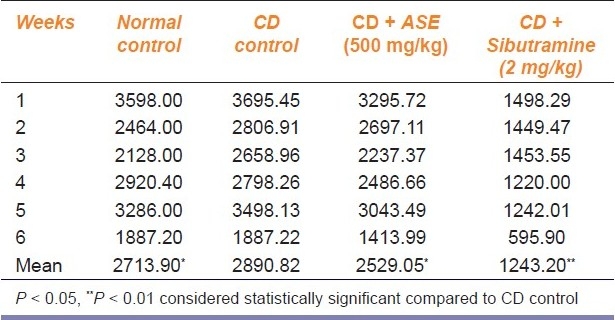

Effect of ASE on calorie intake

There was a significant (P < 0.05) increase in calorie intake per week among the cafeteria diet-fed rats as compared to the normal diet-fed rats. However, the rats treated with ASE and sibutramine showed a significant (P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively) decrease in calorie intake per week [Table 3].

Table 3.

Effect of Argyreia speciosa roots extract on calorie intake (kcal/week) for six rats fed with cafeteria diet (CD). (n = 6)

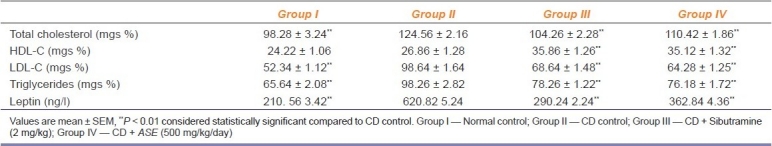

Effect on ASE on Serum Biochemical Parameters

Feeding of cafeteria diet caused a significant (P < 0.01) increase in serum levels of total-cholesterol, LDL, and triglycerides as compared to normal diet fed rats. In contrast, ASE treatment significantly (P < 0.01) inhibited the increase in the serum levels of leptin, total-cholesterol, LDL, and triglycerides, which were induced by a cafeteria diet. However, the HDL concentration was significantly (P < 0.01) increased by ASE treatment in comparison to the CD control group [Table 4]. The atherogenic index was calculated to be 0.135, 0.203, 0.030, and 0.004 for the normal control, CD control, ASE (500 mg/kg), and sibutramine (2 mg/kg)-treated group of rats, respectively.

Table 4.

Effect of Argyreia speciosa root extract on the serum biochemical parameters in rats fed with cafeteria diet (n = 6)

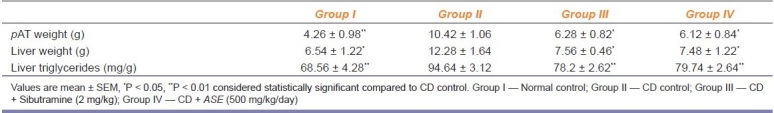

Effect of ASE on liver weight, parametrial adipose tissue weight, and liver triglyceride content

Feeding a high-fat CD for six weeks produced a significant (P < 0.05) increase in parametrial white adipose tissue weight as compared to normal diet-fed rats [Table 5]. Furthermore, the CD also induced fatty liver, with the accumulation of triglycerides when compared to the normal control group. Treatment with ASE significantly reduced the weight of the liver, parametrial adipose tissue, and the liver triglycerides. [Table 5].

Table 5.

Effect of Argyreia speciosa root extract on the parametrial adipose tissue (pAT) weight, liver weight, and liver triglycerides in rats fed with cafeteria diet (n = 6)

Effect of ASE on pancreatic lipase activity

The ASE produced a dose-dependent inhibition of pancreatic lipase activity at concentrations of 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 mg/ml, as indicated by the reduction in the amount of free fatty acids released from triolein per hour. The amounts of free fatty acids released from triolein were found to be 0.30, 0.24, 0.22, and 0.19 μmol/ml/hour by 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 mg/ml of ASE, respectively.

Discussion

Various animal models of obesity have been used to emulate obesity-like condition in humans, in order to develop effective antiobesity treatments. Among the animal models of obesity, rats that are fed a high-fat diet are considered useful; a high percentage of fat in their diet is considered to be an important factor in the development of obesity, leading to the accumulation of body fat, even in the absence of an increase in calorie intake.[11]

The present study showed that the administration of a CD for six weeks, in rats, produced obesity-like conditions, with increase in body weight, parametrial adipose tissue weight, and serum lipid levels. Furthermore, it also induced a fatty liver with the accumulation of hepatic triglycerides. Treatment with ASE at a dose of 500 mg/kg/day, significantly reduced the increase in body weight induced by a CD — a clear sign of an antiobesity effect. The calorie intake measured once every week showed a significant reduction in calorie intake in CD plus ASE-treated rats as compared to CD control rats. This result suggests that the body weight reducing effect of ASE in cafeteria diet-fed rats may be produced due to its hypophagic property.

Significant increase in serum lipids, such as total cholesterol (TC), LDL-C, and triglycerides (TG) is observed in obese animals and humans. In addition, there is a decrease in HDL / LDL ratio. Thus, alteration of lipid profiles can be used as an index of obesity. Treatment with ASE caused significant changes in the blood parameters, including decreased levels of TC, LDL-C, and TG, but increased HDL-C. These results indicate a significant improvement in AIP by the treatment of ASE. AIP correlates with the size of the pro- and antiatherogenic lipoprotein particles and is known to predict a cardiovascular risk.[12] An AIP value of less than 0.10 predicts a low cardiovascular risk, which is observed in animals treated with ASE and sibutramine.

Leptin, a 167 amino acid protein, is synthesized and secreted mainly by the adipose tissue, in approximate proportion to the fat stores. Several authors have reported that consumption of a high-fat diet results in the development of leptin resistance in rodents, marked by an increased circulating leptin level, and is measured as a failure of leptin either to inhibit food intake or to induce weight loss.[13] In the present study, the serum leptin was raised in the CD control group; however, treatment with ASE resulted in a significant decrease in serum leptin levels when compared to the CD control group.

The extract produced a significant decrease in the liver and parametrial adipose tissue weight and the accumulation of liver triglycerides in comparison with the CD control group. The rate of reduction of body weight corresponded with that in the parametrial adipose tissue weight. It is well known that the dietary lipid is not directly absorbed from the intestine unless it has been subjected to the action of the pancreatic lipase enzyme. The two products formed by the hydrolysis of fat in the presence of pancreatic lipase enzyme are fatty acids and 2-monoacylglycerols, which are absorbed.[14] Thus, the inhibition of this enzyme is beneficial in the treatment of obesity. Orlistat, an approved antiobese drug is clinically reported to prevent obesity and hyperlipidemia through the increment of fat excretion into the feces and inhibition of the pancreatic lipase enzyme.[15] The ASE at concentrations of 250, 500, 1000, and 2000 mg/ml inhibited the action of the pancreatic lipase enzyme in vitro, in a dose-dependent manner, as indicated by the reduction in the amount of free fatty acids released.

It has been reported that the saponins in Panax ginseng, Platycodi radix, and Panax japonicus rhizomes, all belonging to the family of the triterpenoid family of saponins, showed strong inhibitory effects on the pancreatic lipase in vitro and suppressed the increase in body weight induced by a high-fat diet in vivo.[16ߝ18] In this study, the saponin glycosides that are found to be present in the ASE might be responsible for the inhibition of in vitro pancreatic lipase activity, and consequently, the reduction of body weight in cafeteria diet-induced obese rats.

To conclude, ASE might exert its antiobesity action through the inhibition of intestinal absorption of dietary fat, its hypophagic activity, and its hypolipidemic activity. The present study confirms the rational basis for its use in traditional medicine for the treatment of obesity. However, further studies are under progress to isolate and characterize the phytoconstituents responsible for the antiobese activity.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Pi-Sunyer X. The Medical risks of obesity. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:21–33. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.11.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garg C, Khan SA, Ansari SH, Garg M. Prevalence of obesity in Indian women. Obes Rev. 2010;11:105–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Padwal RS, Majumdar SR. Drug treatments for obesity: Orlistat, Sibutramine and Rimonabant. Lancet. 2007;369:71–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chadhya YR. The Wealth of India: A dictionary of Indian raw materials and industrial products. New Delhi, India: Publications and Information Directorate; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warrier PK, Nambiar VP, Ramankutty C. Indian Medicinal Plants: A compendium of 500 species. Chennai, India: Orient Longman Ltd; 2002. pp. 106–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gokhale AB, Damre AS, Saraf MN. Investigations into immunomodulatory activity of Argyreia speciosa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;84:109–14. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habbu P, Shastry R, Mahadevan KM, Joshi H, Das S. Hepatoprotective and antioxidant effects of Argyreia speciosa in rats. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2008;5:158–64. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v5i2.31268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachhav RS, Gulecha VS, Upasani CD. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity of Argyreia speciosa root. Indian J Pharmacol. 2009;41:158–61. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.56066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris RB. The impact of high or low fat cafeteria foods on nutrient intake and growth of rats consuming a diet containing 30 % energy as fat. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993;17:307–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Belfrage P, Vaughan M. Simple liquid-liquid partition system for isolation of labeled oleic acid from mixtures with glycerides. J Lipid Res. 1969;10:341–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kusunoki M, Hara T, Tsutsumi K, Nakamura T, Miyata Y, Sakakibara F, et al. The lipoprotein lipase activator, NO-1886, suppresses fat accumulation and insulin resistance in rats fed a high fat diet. Diabetologia. 2000;43:875–80. doi: 10.1007/s001250051464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frohlich J, Dobiasova M. Fractional esterification rate of cholesterol and ratio of triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol are powerful predictors of positive findings on coronary angiography. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1873–80. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.022558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin S, Thomas TC, Storlien LH, Huang XF. Development of high fat diet induced obesity and leptin resistance in C57BI/6J mice. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:639–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verger R. Pancreatic lipase. In: Bergstrom B, Brackman HL, editors. Lipase. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1984. pp. 83–150. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drent ML, Larsson I, William-Olsson T, Quaade F, Czubayko F, von Bergmann K, et al. Orlistat (RO 18-0647), a lipase inhibitor, in the treatment of human obesity: A multiple dose study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:221–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han LK, Zheng YN, Xu BJ, Okuda H, Kimura Y. Saponins from platycodi radix ameliorate high fat diet-induced obesity in mice. J Nutr. 2002;132:2241–5. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.8.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yun SN, Moon SJ, Ko SK, Im BO, Chung SH. Wild ginseng prevents the onset of high-fat diet induced hyperglycemia and obesity in ICR mice. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;7:790–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02980150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han LK, Zheng YN, Yoshikawa M, Okuda H, Kimura Y. Antiobesity effects of chikusetsusaponins isolated from Panax japonicus rhizomes. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2005;6:5–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]