Abstract

Amphiphilic star polymers offer substantial promise for a range of drug delivery applications owing to their ability to encapsulate guest molecules. One appealing but under-explored application is transdermal drug delivery using star block copolymer reverse micelles as an alternative to the more common oral and intravenous routes. 6- and 12-arm amphiphilic star copolymers were prepared via atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) of sequential blocks of polar oligo (ethylene glycol)methacrylate and nonpolar lauryl methacrylate from brominated dendritic macroinitiators based on 2, 2-bis(hydroxymethyl) propionic acid. These star block copolymers demonstrate the ability to encapsulate polar dyes such as rhodamine B and FITC-BSA in nonpolar media via UV/Vis spectroscopic studies and exhibit substantially improved encapsulation efficiencies, relative to self-assembled “1-arm” linear block copolymer analogs. Furthermore, their transdermal carrier capabilities were demonstrated in multiple dye diffusion studies using porcine skin, verifying penetration of the carriers into the stratum corneum.

Keywords: transdermal delivery, star block copolymer, polymer micelle, dye encapsulation, atom transfer radical polymerization

INTRODUCTION

The field of carrier-mediated drug delivery offers promise to vastly improve the efficacy of existing therapeutics. To date, most drugs are administered orally or by needle (parenteral) injection. These methods, while convenient, have several disadvantages. Oral administration decreases the drug’s bioavailability by exposing the drug to the acidic, enzyme-rich environment of the gastrointestinal tract as well as to first-pass liver metabolism. This process decreases the amount of drug that actually reaches the circulatory system. While parenteral delivery bypasses the gastrointestinal tract and the liver by injecting the drug directly into the tissues, the associated pain can reduce compliance, the injection site is prone to infection, and proper administration requires experienced medical personnel.1,2

Because of these disadvantages, there has been a need for alternative routes for drug administration. A particularly appealing alternative is transdermal drug delivery which involves drug transport across intact skin, thereby bypassing the gastrointestinal tract and first-pass liver metabolism which increases the drug’s bioavailability. This route of delivery is also patient-friendly, non-invasive, and easily self-administered.3,4

Despite its advantages, unassisted transdermal drug delivery is only useful for a limited number of drugs. Earlier investigations suggest that only relatively small hydrophobic molecules can easily pass through the extracellular lipids of the skin.5,6 The use of nanoscale carriers shows potential for a general method for the delivery of a more wide range of drugs, and initial research focused largely on optimization of liposomal carriers, in which more polar drugs can be encapsulated within the hydrophilic interior.7–10 While liposomes are effective at loading high concentrations of drugs, they typically self-assemble into carriers which are substantially larger (~100–200nm) than the intercellular spacing of the corneocytes in the outermost layer of the skin.11 Because liposomes are held together by a reversible association, they can also be susceptible to dissociation or payload leakage which can result in premature release of drugs, toxicity issues, or even precipitation of the drug in vivo.12

Alternatively, traditional micelles can be prepared via a similar self-assembly process to yield even smaller carriers of a more appropriate scale for transdermal delivery. For self-assembled micelles, a concentration-dependent, dynamic equilibrium exists between individual surfactant molecules and micellar aggregates. Inherent to each amphiphile/solvent system is a critical micelle concentration (CMC) above which the association into micelles is favored and below which they dissociate. Under the dilution and polarity changes associated with transdermal diffusion, disaggregation and payload leakage are concerns.13 To address these concerns a technique is required to generate small (< 100nm) but robust carriers.

Drug delivery in polymer micelles has been the subject of extensive research because the polymeric systems can be easily prepared from commercially available materials, they exhibit smaller sizes than liposomes and lower CMCs than traditional micelles, and they demonstrate prolonged circulation of the drugs.14–16 Several research groups have investigated Pluronic polymers, triblock copolymers consisting of a central block of hydrophobic poly(propylene oxide) between two blocks of hydrophilic poly(ethylene oxide) and demonstrated their administration of drugs in animal models.17–20 A wide range of amphiphilic diblock copolymers have also demonstrated the ability to form polymer micelles, including poly(styrene-b-ethylene oxide),21,22 poly(ethylene oxide-b-β-benzyl L-aspartate),23 poly(lactide-b-ethylene oxide),24 poly(ε-caprolactone-b-ethylene oxide),25 poly(ethylene oxide-b-aspartic acid),26 and poly(acrylamide-b-styrene).27 Amphiphilic homopolymers, bearing both hydrophilic and hydrophobic sidechains on each repeat unit prepared by Thayumanavan and coworkers28–30 were shown to assemble into environment-dependent micelles or inverse micelles. These inverse micelles were shown to encapsulate hydrophilic molecules as they are used to extract peptides from aqueous media.31–33 Although polymeric micelles demonstrated increased stability, and therefore improved circulation times, they still suffer from a dynamic equilibrium because the micelles are composed of a number of individual polymer chains, which can disaggregate.

The use of covalently reinforced micelle-like carriers has potential to circumvent these complications, by removing the dependence on dynamic equilibrium. While a number of researchers have demonstrated the covalent cross-linking of pre-formed liposomes34–36 or polymer micelles,37–40 an attractive alternative approach is to construct micelle-like macromolecules “de novo” in which multiple amphiphilic component are synthesized covalently attached to form amphiphilic star polymers. While smaller stars still are expected to be susceptible to disaggregation, their CMCs should be drastically reduced. Larger stars, on the other hand, are expected to yield single macromolecules that can act independently as micelles and therefore independent of a CMC. Such concentration-independent “unimolecular micelles” were first described by Newkome et al. in 1985 using amphiphilic dendrimers.41 Owing to the sometimes tedious synthesis of larger dendrimers,42–44 and their relatively small carrier capacity, many researchers have investigated the accelerated synthesis of unimolecular micelles from star polymers,45,46 hyperbranched polymers,47–49 and related hybrid architectures.50–53 In the case of star polymers, as the number of arms increases, the CMC should be decreased until a certain threshold when true unimolecular micelles are achieved. This transition for amphiphilic star polymers from self-assembled micelles to unimolecular micelles is not fully understood, and is one of the primary focuses in this study.

A number of routes can be envisioned for the preparation of amphiphilic star block copolymers, the two most obvious including, first, the divergent synthesis of stars outward from a dendritic core via successive polymerization of polar and then non-polar blocks, and second, the convergent synthesis of linear block copolymers, followed by a coupling reaction to a dendritic core. The first route is the most technically simple and rapid approach, as the product can be purified at each step by a simple precipitation, however, the multiplicity of initiating functionalities on each core leads to slow, less consistent polymerizations with broadened polydispersities, and more difficulty in isolating products with exactly analogous block ratios. The second route enables the preparation of carriers with more uniform arms, since all stars can be assembled from the same amphiphilic linear polymer. However this route is much more challenging synthetically because the coupling of multiple linear polymer arms to a single core is difficult to drive to completion, and requires challenging purification, since an excess of linear polymer will be required for high-yielding coupling but cannot be easily removed via techniques such as precipitation. For these reasons, our initial studies involved the divergent polymerization from the core, despite its limitations, in order to provide preliminary data to evaluate if amphiphilic star polymers had sufficient promise as transdermal carriers to justify the more tedious yet more precise approaches to preparing amphiphilic block copolymers.

Herein, we present the synthesis of amphiphilic star block copolymers with 6 and 12 arms, and compared them with “1-arm” linear analogs. Polymers with 6 and 12 arms were selected to be studied because of their ease of synthesis (compared to 24 and 48 arm cores) combined with their likelihood of exhibiting behavior that contrasted traditional “1-arm” linear block copolymers. These polymers were prepared by ATRP54,55 from dendritic cores56 bearing 6 or 12 tertiary bromide functionalities at their periphery.46, 57, 58 Diblocks were prepared by successive polymerization of a hydrophilic monomer, oligo (ethylene glycol) methacrylate (OEGMA), followed by a nonpolar monomer, lauryl methacrylate (LMA). The aggregation of the resulting amphiphilic star polymers was characterized using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS), and their ability to act as carriers59,60 examined by encapsulation of polar dye (rhodamine B) in non-polar solvents, as well as their transport of the dye through porcine skin.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Propargyl alcohol, 2-bromoisobutryl bromide, 1,1,1-tris(hydroxymethyl)ethane, 4-(dimethylamino)-pyridine, Palladium (10% wt on carbon), copper(I) bromide (CuBr, 99.99% metals basis), copper(I) chloride (CuCl), 2,2-bypyridine (bpy), and N, N, N′, N″, N″-pentamethyldiethylene triamine (PMDETA, 98%), and all solvents were used as received. Triethylamine was distilled and stored until use. OEGMA was purified via an alumina column to remove inhibitor and refrigerated until use. LMA was purified via distillation and refrigerated until use. The benzylidene-protected bis-(hydroxyl methyl) propionoic acid (BP-BMPA) anhydride, first generation [G-1]Ph3 and [G-1](OH)6 dendrimers, and second generation [G-2]Ph6 and [G-2](OH)12 dendrimers were synthesized from a known literature procedure.56

Instrumentation

All 1H NMR (400 MHz) and 13C NMR (100MHz) were obtained using a Varian Unity Inova spectrometer (Palo Alto, CA), using the TMS peak for calibration for 1H, and the chloroform solvent peak for 13C. Mass spectral data was acquired using a Bruker Autoflex III matrix assisted laser desorption time of flight mass spectrometer (MALDI-TOF MS) with delayed extraction using the reflector positive ion mode. 9-nitroanthracene, sodium trifluoroacetate, and THF were the matrix, counterion, and solvent, respectively, of choice for preparing the MALDI samples. MALDI samples were prepared using a 1/9/1 dendrimer/matrix/Na+ ratio with stock solutions of 6mg/mL concentration of dendrimer, 15mg/mL concentration of 9-nitroanthracene, and 3mg/mL concentration of counterion. Size exclusion chromatography was carried out on a Waters model 1515 series system (Milford, MA) via elution through three-columns in series from Polymer Laboratories, Inc. consisting of 1) PLgel 5 μm Mixed C (300mm × 7.5mm) and 2) PLgel 5 μm 500 Å (300mm × 7.5mm) columns. The system was fitted with a Model 2487 differential refractometer detector and anhydrous tetrahydrofuran was used as the mobile phase (1mL min−1 flow rate). The SEC calculated molecular weight was based on calibration using linear polystyrene standards. All data collected was processed using Precision Acquire software. All UV spectroscopy was obtained using a Hewlett Packard 8452A Diode Array Spectrophotometer. DLS data was acquired using a Brookhaven 90Plus Particle Size Analyzer. TEM data was obtained with a JEOL 2010 Scanning Transmission Electron Microscope. Porcine skin fluorescence data was obtained using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) and analyzed using Slidebook 5.0 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO).

Preparation of Propargyl 2-bromoisobutyrate

This compound was prepared according to literature procedure61 and purified by column chromatography to yield the product as a yellow liquid (yield 80%). Characterization data agreed with those previously reported.

Preparation of Hexa-bromo Initiator

[G-1](OH)6 was prepared according to literature procedure56 (0.77g, 1.6mmol) was dissolved in 10mL THF, followed by the addition of 5mL NEt3 (35mmol). 2-bromoisobutryl bromide (2.65g, 12mmol) was then added dropwise to the reaction flask and the reaction stirred under N2 for ~12 hours. The reaction mixture was filtered and the filtrate was dissolved in diethyl ether and then washed 3 times with aqueous NaHSO3 and 3 times with aqueous NaHCO3. The collected organic layer was dried over MgSO4 and concentrated. The crude product was purified via column chromatography using 15% ethyl acetate/75% hexanes as the eluent, yielding the initiator as tan/brown crystals (yield: 0.440g (20%)). 1H NMR (400MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.09 (s, 3), 1.36 (s, 9), 1.92 (s, 36), 4.11(s, 6), 4.32 (d, 6), 4.41 (d, 6); 13C NMR (100MHz, CDCl3): δ 17.37, 18.17, 30.84, 39.43, 47.10, 55.56, 66.19, 171.12, 172.03; C44H66O18Br6, [M + Na]+theo = 1384.9, MALDI: [M + Na]+ = 1384.69

Preparation of Dodeca-bromo Initiator

Procedure same as that for the hexa-bromo initiator using [G-2](OH)1256 (0.51g, 0.4mmol), 2-bromoisobutryl bromide (1.814g, 7.9mmol), 20mL THF, and 1.11mL NEt3 (7.9mmol), (yield: 0.391g (30%)). 1H NMR (400MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.05 (s, 3), 1.26 (s, 27), 1.85 (s, 72), 4.06 (s, 6), 4.22 (d, 24), 4.32(d, 12); 13C NMR (100MHz, CDCl3): δ 17.2, 17.85, 18.15, 30.81, 39.42, 46.92, 47.0, 55.63, 172.02, 171.76, 171.79; C98H144Br12O42, [M + Na]+theo = 2975.92, MALDI: [M + Na]+ = 2974.66

General Procedure for polymerization of p-OEGMA-Br for linear and star polymers

A round bottom flask containing OEGMA, ATRP initiator, PMDETA (or 2′, 2′-bipyridine), and methanol was degassed using 2 freeze/pump/thaw cycles. Immediately following a third freeze, CuBr (or CuCl) was added, followed by a pump/thaw cycle. Upon thawing, the reaction flask was allowed to stir under nitrogen at room temperature. Upon termination, the reaction mixture was diluted with dichloromethane and washed with deionized water to remove the copper. The organic layer was then dried over (anhydrous), passed through a MgSO4 plug of silica to remove any excess copper, and precipitated into diethyl ether to yield pure polymer.

Polymerization of 1-arm pOEGMA-Br

General procedure followed using OEGMA (0.892g, 3.23mmol), propargyl 2-bromoisobutyrate30 (0.018g, 0.09mmol), CuCl (0.009g, 0.09mmol), 2,2 -bypyridine (0.014g, 0.09mmol), and 2mL methanol with a reaction time of ~2 hours. (yield: 0.251g (48%))

GPC: MW=6000 (DPOEGMA = 20), PDI= 1.29

Polymerization of 6-arm pOEGMA-Br

General procedure followed using OEGMA (1.99g, 7.22mmol), hexa-bromo initiator (0.015g, 0.011mmol), CuBr (0.016g, 0.011mmol), PMDETA (0.004g, 0.021mmol), and 3 mL methanol with a reaction time of ~18 hours. (yield: 0.145g, (52%))

GPC: MW=23,900 (DPOEGMA = 13), PDI= 1.10

Polymerization of 12-arm pOEGMA-Br

General procedure followed using OEGMA (4.04g, 14.63mmol), dodeca-bromo initiator (0.036g, 0.012mmol), CuBr (0.017g, 0.011mmol), PMDETA (0.004g, 0.021mmol), and 3 mL methanol with a reaction time of ~48 hours. (yield: 0.206g, (51%))

GPC: MW=33,000 (DPOEGMA = 9), PDI= 1.06

General procedure for the preparation of pOEGMA-b-pLMA-Br for linear and star polymers

A round bottom flask containing LMA, pOEGMA-Br, PMDETA, and a methanol/DMF solvent mixture (50:50 v/v) was degassed using 2 freeze/pump/thaw cycles. Immediately following a third freeze, CuBr was added, followed by a pump/thaw cycle. Upon thawing, the reaction flask was placed in an oil bath preheated to ~140° C and allowed to stir under nitrogen. Upon termination, the reaction mixture was diluted with dichloromethane and washed with deionized water to remove the copper. The organic layer was then dried over MgSO4 (anhydrous), passed through a plug of silica to remove any excess copper, and washed with 2-isopropanol to yield pure polymer.

Polymerization of 1-arm pOEGMA-b-pLMA-Br

General procedure followed using LMA (0.092g, 0.116mmol), 1-arm poly(OEGMA)-Br (0.060g, 0.01mmol), CuBr (0.002g, 0.01mmol), PMDETA (0.001g, 0.005mmol), and 8mL methanol/DMF with a reaction time of ~3 hours. (yield: 0.060g (40%))

GPC: MW=9,500 (DPOEGMA = 20, DPLMA = 14), PDI= 1.24

Polymerization of 6-arm pOEGMA-b-pLMA-Br

General procedure followed using LMA (1.25g, 4.53mmol), 6-arm pOEGMA-Br (0.251g, 0.011mmol), CuBr (0.013g, 0.091mmol), PMDETA (0.008g, 0.045mmol), and 6mL methanol/DMF with a reaction time of ~ 24 hours. (yield: 0.198g (35%))

GPC: MW=54, 200 (DPOEGMA = 13, DPLMA = 20), PDI= 1.46

Polymerization of 12-arm pOEGMA-b-pLMA-Br

General procedure followed using LMA (0.808g, 2.93mmol), 12-arm pOEGMA-Br (0.117g, 0.003mmol), CuBr (0.002g, 0.016mmol), PMDETA (0.001g, 0.008mmol), and 8mL methanol/DMF with a reaction time of ~72 hours. (yield: 0.096g (42%))

GPC: MW=65, 000 (DPOEGMA = 9, DPLMA = 10), PDI= 1.39

Dye Solubilization Analysis via UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Because of the insolubility of rhodamine B in non-polar solvents, the ability of the carrier to impart on rhodamine B solubility in in squalane enabled an easily quantifiable measure of the amount of polar guest that could be encapsulated by these carriers in non-polar environments An excess amount of rhodamine B was added to a series of 1, 6, and 12-arm block copolymer solutions of varying concentrations (0.1, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg/ml) in squalane, sonicated for ~1hr, and allowed to sit at room temperature overnight to allow undissolved dye to settle. The samples were then Millipore filtered to remove undissolved dye and absorbance data was acquired on a UV-Vis spectrophotometer within a range near rhodamine B’s wavelength of maximum absorbance (~543nm).

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

Particle size was measured offline using a Brookhaven 90-plus detector (λ=670nm) operating at a scattering angle of 90°, at room temperature. Particle hydrodynamic diameter Dh (the intensity-weighted average diameter) was determined based on the Stokes-Einstein equation. A stock solution of 5.0mg/ml of each block copolymer was analyzed, and serial dilution used to verify aggregation at different concentrations.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

5μL of a 0.25mg/mL stock solution of block copolymer (1, 6, or 12-arm) in DEE was pipette onto a 200 mesh TEM grid with formvar film coated with carbon and dried in air. The grid was then transferred to the TEM sample holder and placed into the TEM. The sample was observed at 120kV.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Using a Franz Cell apparatus maintained at 37°C with PBS buffer in the receptor chamber, porcine skin was treated (for the specified time points) with 250μL of solutions of:

Proflavin (or rhodamine B) in H2O (30 minutes)

Proflavin (or rhodamine B) in squalane (30 minutes)

Block copolymer (1, 6, or 12-arm) in squalane (30 minutes)

Block copolymer (1, 6, or 12-arm) and proflavin (or rhodamine B) in squalane (30 minutes and 2 hours)

The tissue was then fixed in 10% formalin for 24 hours followed by cryo-preservation for 24 hours in each of three sucrose solutions (20, 30, and 40%). Cryo-sections were then stained with 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and imaged. Full-thickness porcine skin was obtained from the Louisiana State University AgCenter Swine Unit.

Results and Discussion

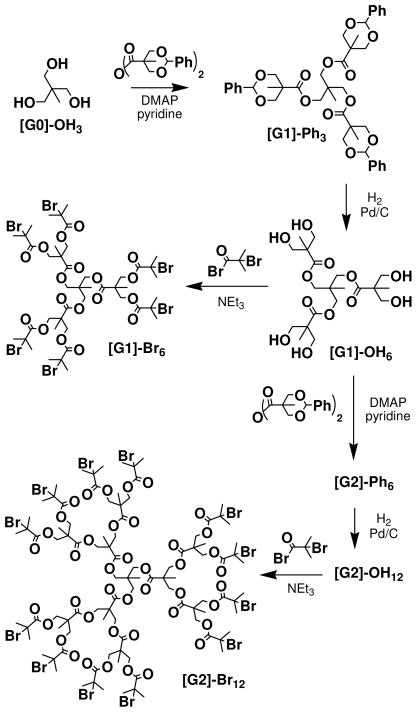

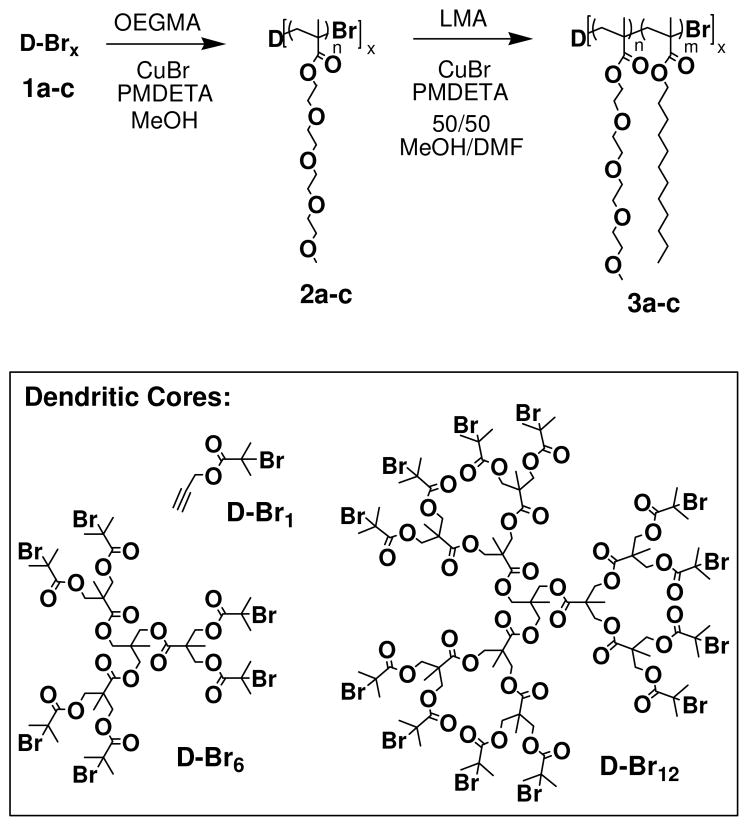

The well-defined star polymers investigated in this study were prepared from dendritic cores based on a 1,1,1-tris(hydroxylmethyl)ethane core and 2, 2,-bis(hydroxylmethyl)propionic acid branching units. The desired initiators were obtained by esterification of these dendritic poly-ol (bearing either 6 and 12 peripheral hydroxyl groups) with 2-bromoisobutyryl bromide (Scheme 1). After purification via column chromatography, these 6- and 12-arm initiators (1b, 1c) were used to polymerize a block of oligo(ethylene glycol)methacrylate (OEGMA) to provide the polar core of the amphiphilic macromolecules (2b, 2c). OEGMA was selected as the inner block to provide water solubility that was independent of pH, as well as provide biocompatibility for the carriers in vivo. ATRP was carried out using Cu(I)Br catalyst with PMDETA ligand at room temperature after a series of freeze-pump-thaw cycles to remove oxygen from the reaction environment. The crude 6- and 12-arm p(OEGMA) homopolymers were diluted with dichloromethane, washed with water to remove the copper salts, filtered through a plug of silica to remove any residual salts, and precipitated into diethyl ether to obtain the pure products. Once isolated, the homopolymers were characterized via both SEC and 1H NMR.

Scheme 1.

Dendrimer and Initiator Synthesis

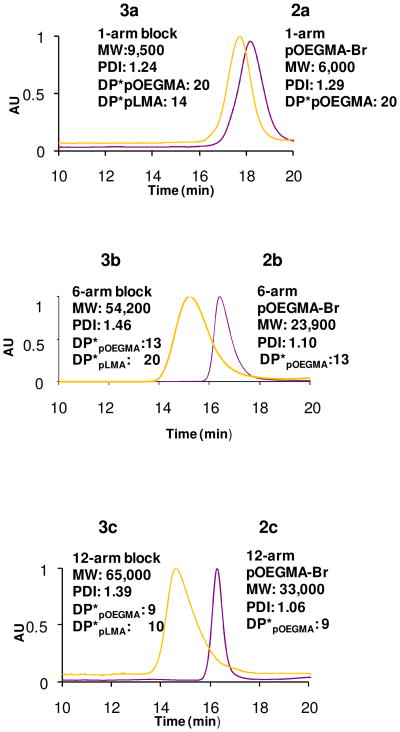

Lauryl methacrylate (LMA) was added as a second block onto the star polymers to provide a non-polar corona that could compatibilize the stars with the lipophilic extracellular matrix. The lauryl side chains were selected because of their similarity in size to the lipophilic hydrocarbon chains in the skin lipids. The p(LMA) blocks were polymerized from the p(OEGMA) star homopolymers by reintroduction of Cu(I)Br/PMDETA catalyst in a degassed solution of LMA and the p(OEGMA) macroinitiators in a 50:50 solution of dimethylformamide (DMF) and methanol heated to 140°C. The 6- and 12-arm block p(OEGMA)-block-p(LMA) copolymers (3b, 3c) were purified and isolated by diluting with dichloromethane and washed with water to remove the copper salts, filtering through a plug of silica gel, and washing with isopropanol. The pure block copolymers were also characterized by 1H NMR and SEC (Figure 1). As observed in previously reported syntheses of star-block copolymers using ATRP, while the initial block of the star homopolymers 2b and 2c exhibited relatively narrow polydispersities (~1.1),62 the addition of a second block lead to a broadening of the PDI (~1.3–1.5).63 This trend was consistent through multiple attempts to prepare these star amphiphiles (supporting information, Table S1) and a representative set was selected for further study (Table 1).

Figure 1.

GPC traces of 1, 6, and 12-arm pOEGMA-Br (purple) and pOEGMA-b-pLMA-Br (yellow).

Table 1.

Molecular weight, PDI, and block ratio, hydrodynamic radius, and hydrodynamic volume data for a) 1-arm, b) 6-arm, and c)12-arm pOEGMA-Br and pOEGMA-b-pLMA-Br.

| Data by GPC | DPOEGMA: DPLMA block ratio | Hydro-dynamic Radius (3) | Hydro-dynamic Volume (3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homopolymer (2) | Block Copolymer (3) | |||||||||

| Mn | PDI | DPOEGMA | Mn | PDI | DPLMA | GPC | NMR | Rh (nm) | Vh (nm3) | |

| a | 6000 | 1.29 | 20 | 9500 | 1.24 | 14 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.95 | 317 |

| b | 23900 | 1.10 | 13 | 54200 | 1.46 | 20 | 0.65 | 1.5 | 8.08 | 2210 |

| c | 33000 | 1,06 | 9 | 65000 | 1.39 | 10 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 9.67 | 3790 |

Because linear block copolymers can themselves self-assemble to form micelles, a 1-arm linear block copolymer with comparable ratios of p(OEGMA) and p(LMA) blocks was prepared to provide a direct comparison to the amphiphilic stars. The linear, or 1-arm, p(OEGMA) homopolymer (2a) and subsequent p(OEGMA)-block-p(LMA) copolymer (3a) were prepared, purified, and characterized in the same manner as the 6- and 12-arm star polymers with the exception that the initiator used was propargyl 2-bromoisobutyrate (1a) and a Cu(I)Cl/2,2-bipyridine (bpy) catalyst system was used to slow the polymerization, in order to target the desired molecular weights.

According to GPC measurements, the masses of the 1-arm p(OEGMA) homopolymer and p(OEGMA)-block-p(LMA) were 6000D and 9500D, respectively corresponding a block ratio (DPOEGMA to DPLMA) of 1.4. The 6-arm homopolymer and block copolymer had masses of 23900D and 54200D, respectively with a block ratio of 0.65. The respective masses of the 12-arm homo and block copolymers were 33000D and 65000D corresponding to a block ratio of 0.9. Because the GPC is calibrated against polystyrene standards, the measured molecular weights are not entirely accurate, making it difficult to directly compare the block copolymer samples. We, therefore, employed 1H NMR to give us more reliable block ratios which were calculated as 1.9, 1.5, and 1.2 for 1-, 6-, and 12-arms, respectively. The number of repeat units calculated by GPC and other characterization data are summarized in Table 1.

Dye Encapsulation Studies

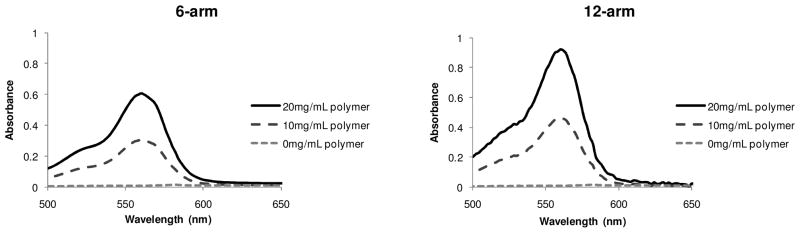

The 6- and 12-arm amphiphilic star block copolymers were constructed with the topology of reverse micelles, having a hydrophilic interior (OEGMA blocks) and a hydrophilic exterior (LMA blocks) but with a covalently linked structure. As a preliminary investigation of their encapsulation of polar guests in hydrophobic environments, the stars’ ability to encapsulate a polar dye, rhodamine B, was measured using squalane solvent, a common skin lipid approved for cosmetic use. Rhodamine B exhibits a strong absorbance near 543nm, enabling a simple method for quantifying dye encapsulation. For experimental controls, the UV-visible absorbance of a saturated solution of rhodamine B in both squalane and water, as well as a solution of the block copolymer without dye in squalane were acquired (see supporting material). The saturated rhodamine B/squalane solution was prepared by adding an excessive amount of rhodamine B to squalane, sonicating for 1hr, and allowing the solution to settle for ~12 hours. The solution was then filtered to remove any undissolved rhodamine B. In the same manner, saturated solutions of rhodamine B in 6- and 12-arm block copolymer in squalane were also prepared and their UV absorbance measured (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

UV spectroscopic data for encapsulation of rhodamine in 6 and 12-arm block Wavelength (nm) copolymer in squalane via quantification of UV absorbance.

Neither control study showed any substantial UV activity; therefore, the observed UV activity in the experimental studies verifies that the amphiphilic star polymers are responsible for solubilization of the polar dye. A bathochromic shift to ~560nm was observed, similar to the reports of encapsulation in amphiphilic dendrons,64 suggesting the dye is being solvated by the polar microenvironment of the OEGMA chains. In addition, when the concentration of the amphiphilic polymer was increased, the UV absorbance of the dye also increased, confirming the role of the polymers in solubilizing the polar dye. Using a calibration curve from known concentrations of rhodamine B in water the number of encapsulated dyes is approximated as 11.2 per molecule of 6-arm block copolymer and 17.2 per molecule of 12-arm block copolymer.

The dye encapsulation procedure for the “1-arm” polymer was analogous to the procedure described for the amphiphilic stars. UV dye encapsulation studies suggest an approximate CMC of 2.5mg/ml as there is no observed absorbance for dye-saturated solutions below this concentration of the linear block-copolymer (Figure 3). The encapsulation studies also confirmed that the 6-arm and 12-arm block copolymer both exhibit a slightly reduced CMC near 1mg/mL; however, the negligible encapsulation of the dye at lower concentrations suggest that these relatively small amphiphilic star polymers do not exhibit true unimolecular micelle behavior, but require aggregation in order to form effective reverse micelles. Above the CMC, the “1 arm” polymer does exhibit solubilization of rhodamine, however, direct comparisons with the same amount (by weight) of both the 6- and 12-arm stars verify a higher loading (by polymer weight) of the dye in the stars, verifying that the star polymers are more efficient at guest encapsulation. There are a number of possible explanations for the increased efficiency, including that they form larger micelles with more payload capacity, or that the micelles themselves are not larger but that the equilibrium between the inactive free amphiphile and the active micellar aggregate more strongly favors micellization for the stars.

Figure 3.

Schematic and UV spectroscopy of encapsulation of proflavin in 1-arm and 6-arm block copolymer in squalane.

In order to clarify the nature of the improved encapsulation, the amphiphilic polymers’ aggregation behavior was probed via both DLS and TEM (Figure 4). Because squalane was not sufficiently volatile for carrying out TEM experiments, a comparable non-polar but highly volatile solvent, diethyl ether, was required for the TEM studies. DLS data was acquired in both diethyl ether and squalane to verify that the aggregation behavior was similar for both of these non-polar solvents. Both TEM and DLS verified that all of the polymers examined yielded aggregates in solution. In the case of the linear “1-arm” amphiphilic polymer, 3a, in squalane the DLS number distribution data exhibited large aggregate sizes of 175–250nm which were consistent with the large spherical structures observed in TEM, as well as a trace amount of even larger aggregates between 700–800nm. In the case of both the 6-arm and 12-arm polymers, the aggregates observed in both TEM and DLS were consistently smaller over a range of concentrations. In diethyl ether, for concentrations between 2 and 0.5 mg/ml, the 6-arm polymer, 3b, consistently exhibited a number distribution mean diameter of ~50nm, that included a major distribution around ~45nm and a minor distribution of larger aggregates around 250–500nm. Their aggregation behavior in squalane was a little less consistent, but exhibited the same approximate sizes for both small and large aggregates. The 12-arm star block copolymer, 3c, also exhibited small aggregates with a number distribution mean diameter of ~70nm. These again consisted of a major distribution near 70nm, and a minor distribution of larger aggregates around 250–300nm. In comparison, their aggregates in squalane were observed to be consistently smaller, with a number distribution mean diameter around ~45nm.

Figure 4.

DLS (number distribution) in squalene and TEM of a) 1-arm pOEGMA-block-pLMA copolymer (3a), b) 6-arm pOEGMA-block-pLMA copolymer (3b), and c) 12-arm pOEGMA-block-pLMA copolymer (3c).

In an attempt to provide a crude approximation of the aggregation structure, the hydrodynamic radii were calculated from GPC data (Table 1) and compared with molecular modeling (extended chain length 1-arm: 8–10nm; 6 arm: 8–10nm; 12-arm 5–7nm.) It is apparent from these calculations that the observed aggregates of the “1-arm” polymer are substantially larger than a simple spherical micelle with a polar core block, and a non-polar peripheral block. The 6-arm and 12-arm aggregates, on the other hand, are near to the size that might be expected for loosely packed micellar aggregates.

In addition, the aggregation number can be crudely approximated by correlating the hydrodynamic volume of the individual star polymers as measured by GPC, to the volume of the aggregates as determined by DLS. Assuming a hydrodynamic volume of 2210nm3 (Table 1), approximately 20 of the 6-arm stars could aggregate to fill the volume of the 45nm assemblies, while the 45nm diameter of the 12-arm star aggregates in squalane corresponds to a maximum of about 10 stars per aggregate. The 317nm3 linear diblocks, on the other hand, could exhibit aggregation numbers as high as 104 within the 200nm diameter assemblies observed in the DLS. While these approximations are admittedly crude ones, they provide a clear contrast between the aggregation behaviors of the linear block copolymers and the star block copolymers. Although the amphiphilic star polymers clearly do not act as “unimolecular” micelles, the UV and light scattering data seem to suggest that they do form smaller, more stable aggregates than would be seen with traditional linear block copolymers. It should also be noted that while the size of the star-block copolymer aggregates in squalane does not seem to change significantly between the 6 and 12-arm stars, the aggregation number for the 12-arm stars is cut in half.

Because the size of the star polymer aggregates was larger than many proteins, the star block copolymer’s ability to encapsulate larger biomolecules in non-polar solvents was also tested. An encapsulation experiment was performed by monitoring the UV absorbance of fluorescein isothiocyanate labeled bovine serum albumin (FITC-BSA) in non-polar solvents. The radius of gyration of unmodified bovine serum albumin in aqueous solution had previously been measure as 3.2nm,65 an order of magnitude smaller than the observed star copolymer aggregates. The experimental setup is performed using the identical procedure as that with the rhodamine B, comparing the absorbance of the labeled peptide in the presence or absence of the amphiphilic star-polymers (Figure 5). In 5mg/mL concentration of 6-arm block copolymer in diethyl ether, fluorescence was observed, verifying the encapsulation of the protein by the amphiphilic star polymers. Encapsulation is also observed for the 12-arm block copolymer, but not in an appreciable amount, possibly due to the increased steric crowding caused by additional polymer arms around the core of the star polymer. This contrasts the increased number of Rhodamine B dye molecules that could be encapsulated by the 12-arm star polymers relative to the 6-arm stars, suggesting that the aggregates of the 12-arm stars perhaps have more, but smaller, void spaces for encapsulation. Also observed was a strong hypsochromic shift (near 400nm) which is probably due to the increased sterics of the 12-arm polymer.

Figure 5.

UV spectroscopy of a) FITC-BSA in water and b) 6-arm block copolymer with encapsulated FITC-BSA and a control with no FITC-BSA.

Skin diffusion studies

Finally, in order to investigate our initial goal of preparing efficient transdermal carrier macromolecules, we tested the amphiphilic block copolymers’ ability to transport encapsulated dyes through porcine skin. With a physiology, lipid composition, and total lipid content of the stratum corneum similar to human skin, porcine skin makes a suitable model to assess transcutaneous transport.66 The porcine stratum corneum is slightly thicker than the human stratum corneum; however, the thickness of the entire epidermis is comparable between the two species. Because squalane is major component in the oily secretions in human skin, and approved by the FDA for use in cosmetics, it was selected as the solvent for formulation for the transdermal diffusion studies. Solutions of the 1, 6, and 12-arm star polymers and proflavin dye in squalane were applied to the skin in a diffusion chamber maintained at 37°C for 2 hours. Control samples included untreated porcine skin, as well as skin treated with proflavin and water, skin treated with proflavin and squalane, and skin treated with 6- or 12-arm block copolymer and squalane (but without dye). These control samples were also applied for 2 hours. The tissue was then fixed in 10% formalin for 24 hours followed by cryo-preservation for 24 hours in each of three sucrose solutions (20, 30, and 40%) to remove any excess water. Cryo-sections were stained with DAPI, staining the cell nuclei of the dermis and viable epidermis blue. Cross-sections of the skin were taken and imaged using a wide-frame microscope. All of the control samples without dye exhibited only limited signal in the green wavelengths from skin autofluorescence, while those with proflavin dye without the carrier exhibited fluorescence only from the surface of the skin (Figure S2, Supporting Information). The skin samples with the star-polymer carriers, on the other hand, exhibited the strongest fluorescence of all of the samples in the stratum corneum, the area between the surface of the skin, and the viable dermis (marked by the blue fluorescence of the cell nuclei). When comparing the 1, 6, and 12 arm star polymers, the 1 arm showed strong fluorescence only from the surface of the skin, where the dye was deposited with the polymer. The 6 arm exhibited a slight increase of fluorescence, whereas the 12-arm showed a substantial fluorescence throughout the stratum corneum (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Wide-Frame Fluorescence Microscopy images of porcine skin treated with 1, 6, and 12-arm block copolymer/proflavin/squalane.

In order to confirm these initial studies, and remove the complication of autofluorescence, an analogous set of experiments was carried out with rhodamine B dye as the fluorescent probe encapsulated by the star polymers. Because the λmax of rhodamine B was in a region with reduced autofluorescence of the skin (550 nm) it was assumed this would be a better dye for confirming the transdermal diffusion of the star polymers into the stratum corneum. Similar results were observed with this dye, where the 1-arm linear polymer showed primarily surface fluorescence, the 6-arm star polymer exhibit weak but noticeable fluorescence in the outer regions of the stratum corneum, and the 12-arm star polymer exhibited strong fluorescence, penetrating deep into the epidermis. These results confirmed the transdermal transport of the amphiphilic multi-arm star polymers through the stratum corneum and into the underlying skin.

While the exact causes of this enhanced fluorescent in the case of the amphiphilic star polymers are not certain, it is hypothesized that the improved diffusion is likely related to the fact that the self-assembled micelles are smaller, and therefore can more easily penetrate the narrow (<100nm) intercellular space of the epidermis. In addition, preliminary evidence suggests that the 12-arm star polymers exhibit both increased payload capacity and lower aggregation numbers which suggest improved stability relative to the carriers with a smaller number of arms.

Conclusion

The ability of the star block copolymers to encapsulate a hydrophilic compound in a hydrophobic environment has been demonstrated by numerous research groups, and it was hypothesized that this property might enable their use as carriers for efficient transdermal drug delivery. While the relatively small number of arms (6 or 12) on the described amphiphilic star block copolymers did not allow for true unimolecular micelle properties, they did exhibit improved encapsulation efficiency of polar dyes and reduced CMC relative to 1-arm linear analogs. The block copolymers also exhibited vastly improved transport of polar dyes into the stratum corneum of porcine skin samples, in stark contrast to the 1-arm linear systems. One weakness of this approach is that the ratios of the block copolymers are not exactly analogous for each of the different samples, however these important initial results justify pursuing alternative synthetic routes which can access more exact block ratios as well as higher numbers of amphiphilic arms in order to fully understand the parameters involved in optimizing such star polymers as transdermal drug carriers.

Supplementary Material

Figure 7.

Wide-Frame Fluorescence Microscopy images of porcine skin treated with 1, 6, and 12-arm block copolymer/rhodamine/squalane.

Scheme 2.

ATRP of Dendritic Star pOEGMA-b-pLMA-Br

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tulane University, the National Institute of Health (NIH 1RO1 EB006493-01) and by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command under Award No. W81XWH-07-1-0136 for financial support of this research and the Louisiana Board of Regents for a Graduate Fellowship Grant (DEP). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and are not necessarily endorsed by the U. S. Army. We thank the AgCenter Swine Unit for providing porcine skin samples, and the laboratories of Wayne Reed and Alina Alb (Tulane Physics) for use of their DLS instrumentation and assistance with data acquisition and interpretation by Alina Alb and Zheng Li. Additionally, we would like to thank the Chemistry Department of Washington University in St. Louis, particularly Professor Karen Wooley and her research group for graciously allowing us to work in their labs as a result of our evacuation from New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Supplementary UV spectroscopic control data, fluorescence microscopy control data, additional GPC data and hydrodynamic radius calculations, and concentration dependent dynamic light scattering data. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Park JH, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR. J Controlled Release. 2005;104:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer R. Nature. 1998;392:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams A. Transdermal and Topical Drug Delivery. 1. Pharmaceutical Press; London: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prausnitz MR, Langer R. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1261–1268. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheupin RJ. J Invest Dermatol. 1965;45:334–345. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheupin RJ, Blank IH. Physiol Rev. 1971;51:702–747. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1971.51.4.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mezei M, Gulasekharam V. Life Sci. 1980;26:1473–1477. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul A, Cevc G, Bachhawat BK. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:3521–3524. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Touitou E, Dayan N, Begelson L, Godin B, Eliza M. J Controlled Release. 2000;65:403–418. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinico C, Fadda AM. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. 2009;6:813–825. doi: 10.1517/17425240903071029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Albery WH, Hadgraft J. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1979;31:140–147. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1979.tb13456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torchilin VP. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2005;4:145–160. doi: 10.1038/nrd1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torchilin VP. Pharm Res. 2007;24:2333–2334. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9463-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kataoka K, Kwon GS, Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y. J Controlled Release. 1993;24:119–132. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mu L, Elbayoumi TA, Torchilin VP. Int J Pharm. 2005;306:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torchilin VP. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2549–2559. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabanov AV, Batrakova EV, Melik-Nubbarov NS, Fedoseev NA, Dorodnych TY, Alakhov VY, Chekhonin VP, Nazaro IR, Kabanov VA. J Controlled Release. 1992;22:141–157. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Batrakova EV, Dorodonych TY, Klinskii EY, Kliushnenkova EN, Shemchukova OB, Goncharova ON, Arjakov SA, Alakhov VY, Kabanov AV. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1545–1552. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Batrakova EV, Han H-Y, Miller DW, Kabanov AV. Pharm Res. 1998;15:1525–1532. doi: 10.1023/a:1011942814300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Danson S, Ferry D, Alakhov V, Margison J, Kerr D, Jowle D, Brampton M, Halbert G, Ranson M. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2085–2091. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu R, Winnik MA, Hallett FR, Riess G, Crocher MD. Macromolecules. 1991;24:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilhelm M, Zhao C-L, Wang Y, Xu R, Winnik M, Mura J-L, Riess G, Croucher MD. Macromolecules. 1991;24:1033–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon G, Naito M, Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y, Kataoka K. Langmuir. 1993;9:945–949. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hagan SA, Coombes AGA, Garnett MC, Dunn SE, Davies MC, Illum L, Davis SS, Harding SE, Purkiss S, Gellert PR. Langmuir. 1996;12:2153–2161. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin I, Kim S, Lee Y, Cho C, Sung Y. J Controlled Release. 1998;51:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(97)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yokoyama M, Okano T, Sakurai Y, Suwa S, Kataoka K. J Controlled Release. 1996;39:351–356. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dowling KC, Thomas JK. Macromolecules. 1990;23:1059–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basu S, Vutukuri DR, Shyamyro S, Sandanaraj BS, Thayumanavan S. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9890–9891. doi: 10.1021/ja047816a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savariar EN, Aathimanikandan V, Thayumanavan S. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:16224–16230. doi: 10.1021/ja065213o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kale TM, Klaiker A, Popere B, Thayumanavan S. Langmuir. 2009;25:9660–9670. doi: 10.1021/la900734d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Combariza MY, Savarian EN, Vutukuri DR, Thayumanavan S, Vachet RW. Anal Chem. 2007;79:7124–7130. doi: 10.1021/ac071001d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodthongkum N, Washington JD, Savarian EN, Thayumanavan S, Vachet RW. Anal Chem. 2009;81:5046–5053. doi: 10.1021/ac900661e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodthongkum N, Chen Y, Thayumanavan S, Vachet RW. Anal Chem. 2010;82:3686–3691. doi: 10.1021/ac1000256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu S, Sisson TM, O’Brien DF. Macromolecules. 2001;34:465–473. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu S, O’Brien DF. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6037–6042. doi: 10.1021/ja0123507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X-Y, Zeng G-M, Wang Y-L, Wang J-B, Xu X-H, Zhou T-T, Yan H-K. Chin J Chem. 2008;26:439–444. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan D, Turner JL, Wooley KL. Macromolecules. 2004;37:7109–7115. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun G, Hagooly A, Xu T, Nystrom AM, Li Z, Rossin R, Moore DH, Wooley KL, Welch MJ. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:1997–2006. doi: 10.1021/bm800246x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Y, Bertrand J, Tong X, Zhao Y. Langmuir. 2009;25:13151–13157. doi: 10.1021/la901835z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.He J, Tong X, Tremblay L, Zhao Y. Macromolecules. 2009;42:7267–7270. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newkome GR, Yao Z, Baker GR, Gupta VK. J Org Chem. 1985;50:2003–2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomalia DA, Baker H, Dewald J, Hall M, Kallos G, Martin S, Roeck J, Ryder J, Smith P. Macromolecules. 1986;19:2466–2468. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newkome GR, Yao Z, Baker GR, Gupta VK, Russo PS, Saunders MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1986;108:849–850. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hawker CJ, Fréchet JMJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7638–7647. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meier MAR, Gohy J-F, Fustin C-A, Schubert US. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:11517–11521. doi: 10.1021/ja0488481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kul D, van Renterghem LM, Meier MAR, Strandman S, Tenhu H, Yilmaz SS, Schubert US, du Prez FE. J Polym Sci Part A: Polym Chem. 2008;46:650–660. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim YH, Webster OW. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4592–4593. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawker CJ, Lee R, Fréchet JMJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4583–4588. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krämer M, Stumbé J-F, Türk H, Krause S, Komp A, Delineau L, Prokhorova S, Kautz H, Haag R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;42:4252–4256. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021115)41:22<4252::AID-ANIE4252>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gitsov I, Fréchet JMJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:3785–3786. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heise A, Hedrick JL, Frank CW, Miller RD. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:8647–8648. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang F, Bronich TK, Kabanov AV, Rauh RD, Roovers J. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:397–405. doi: 10.1021/bc049784m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kreutzer G, Ternat C, Nguyen TQ, Plummer CJG, Månson J-AE, Castelleto V, Hamley IA, Sun F, Sheiko SS, Herrmann A, Ouali L, Sommer H, Feiber W, Velazco MI, Klok H-A. Macromolecules. 2006;39:4507–4516. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matyjaszewski K, Wang J-S. Macromolecules. 1995;28:7901–7910. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matyjaszewski K, Xia J. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2921–2990. doi: 10.1021/cr940534g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ihre H, Padilla OL, Fréchet JMJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5908–5917. doi: 10.1021/ja010524e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao YL, Shuai XT, Chen CF, Xi F. Macromolecules. 2004;37:8854–8862. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lepoittevin B, Matmour R, Francis R, Taton D, Gnanou Y. Macromolecules. 2005;38:3120–3128. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hawker CJ, Wooley KL, Fréchet JMJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:4375–4376. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stevelmans S, van Hest JCM, Jansen JFGA, van Boxtel DAFJ, de Berg EMM, Meijer EW. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:7398–7399. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi G-Y, Tang X-Z, Pan C-J. J Polym Sci Part A: Polym Chem. 2008;46:2390–2401. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Agnot S, Murthy S, Taton D, Gnanou Y. Macromolecules. 1998;31:7218–7225. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nese A, Monáček J, Juhari A, Yoon JA, Koynov K, Kowalewski T, Matyjaszewski K. Macromolecules. 2010;43:1227–1235. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vutukuri DR, Basu S, Thayumanavan S. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15636–15637. doi: 10.1021/ja0449628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Santos SF, Zanette D, Fischer H, Itri R. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2003;262:400–408. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9797(03)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hammond SA, Tsonis C, Sellins K, Rushlow K, Scharton-Kersten T, Colditz I, Glenn GM. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2000;43:45–55. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.