Abstract

Do infants develop meaningful social preferences among novel individuals based on their social group membership? If so, do these social preferences depend on familiarity on any dimension, or on a more specific focus on particular kinds of categorical information? The present experiments use methods that have previously demonstrated infants’ social preferences based on language and accent, and test for infants’ and young children’s social preferences based on race. In Experiment 1, 10-month-old infants took toys equally from own- and other-race individuals. In Experiment 2, 2.5-year-old children gave toys equally to own- and other-race individuals. When shown the same stimuli in Experiment 3, 5-year-old children, in contrast, expressed explicit social preferences for own-race individuals. Social preferences based on race therefore emerge between 2.5 and 5 years of age and do not affect social preferences in infancy. These data will be discussed in relation to prior research finding that infants’ social preferences do, however, rely on language: a useful predictor of group or coalition membership in both modern times and humans’ evolutionary past.

Adults’ social interactions with novel individuals are guided not only by the actions of those individuals, but also by the social categories to which they belong. Adults particularly attend to gender, race and age in evaluating people (Fiske, 1998), and their social judgments are influenced by others’ language and accent as well (Giles & Billings, 2004; Gluszek & Dovidio, 2010). Research in developmental psychology suggests that category-based social preferences emerge early in development, and raises questions concerning the processes that produce these preferences. The present research attempts to shed light on the processes governing children’s social category-based preferences by assessing infants’ and young children’s social preferences based on race, in relation to prior work demonstrating young children’s preferences based on language and accent.

On one theory, infants and children tend to prefer people whose properties are most familiar to them. Familiarity, in this case, is not limited to or defined by any particular domain. Indeed, human preferences for the familiar are observed for non-social stimuli such as line drawings, polygons or words, as well as for social stimuli such as faces (Bornstein, 1989; Harrison, 1969; Rhodes, Halberstadt, & Brajkovich, 2001; Zajonc, 1968; 2001). An early preference for the familiar might be adaptive, given that entities that are familiar could, on average, be safer than the unknown. On a different theory, human social preferences might reflect preferences for and reasoning about social kinds (e.g., a naïve sociology that differs from reasoning about non-human kinds; Hirschfeld, 1996). These early preferences for human kinds might even originate in a more specific, evolved, sensitivity to information that distinguished between categories of people within and across social groups throughout our evolutionary history. Within a single social community, all societies in all times are composed of individuals of varying gender, age, and kinship relationships, and so these factors may be particularly psychologically prominent (Kurzban, Tooby, & Cosmides, 2001; Cosmides, Tooby, & Kurzban, 2003; Lieberman, Oum, & Kurzban, 2008). Throughout ancient times, patterns of cooperation and competition would have served as good predictors of coalitional group membership across different social groups, and young children attend to these factors today (Fehr, Bernhard, & Rockenbach, 2008; Cosmides, Tooby, & Kurzban, 2003; Olson & Spelke, 2008; Rhodes, Brickman, & Gelman, under review). Given the speed with which languages and accents evolve, and the apparent difficulty with which we learn a non-native accent as adults, language, too, may have served as a valid predictor of native group membership throughout our evolutionary history (Baker, 2001; Pietraszewski & Schwartz, 2007). Though race-based social categorization is certainly apparent in adults today, the aspects of visual appearance that distinguish members of different racial groups today were likely of little value in distinguishing members of neighboring coalitions in ancestral environments, prior to the onset of long-distance migration (Cosmides et al., 2003; Kurzban et al., 2001). Thus, though race may be an indicator of coalition in many societies today, we likely did not evolve to see race per se as a marker of group membership, and infants and young children may not intuitively award social importance to racial group membership.

Research with children provides some support both for the presence of early familiarity preferences, and also for young children’s more specific preferences for certain social categories. First, considering preferences for familiar social others more generally, young infants’ visual preferences for the faces of novel individuals have been linked to the familiarity of the face categories. Infants of African descent look longer at own-race (Black) faces than at other-race (White) face if they reside in Africa, in a community in which faces of their race predominate, but Ethiopian infants born in Israel look equally to Black and White faces (Bar-Haim, Ziv, Lamy, & Hodes, 2006; see also, Kelly, Quinn, Slater, Lee, Gibson, Smith, Ge, & Pascalis, 2005). Moreover, infants look longer at female faces than male faces if their primary caretaker is female, but may not show this preference if their primary caretaker is male (Quinn, Yahr, & Kuhn, Slater, & Pascalis, 2002; Ramsey-Rennels & Langlois, 2006); furthermore, 3-month-old infants display visual preferences based on gender only when tested with faces of a familiar race (Quinn et al., 2008). By preschool age, children often demonstrate social preferences for individuals of their own gender, race, and age (Aboud, 1988; Alexander & Hines, 1994; Baron & Banaji, 2006; French, 1984; Katz & Kofkin, 1997; Kircher & Furby, 1971; Kowalski & Lo, 2001; Maccoby & Jacklin, 1987). Moreover, children’s preferences for the familiar may underlie the finding that in-group preferences based on race are stronger for majority-race children than for minority-race children (Cameron, Alvarez, Ruble, & Fuligni, 2001). Finally, 5–6 month old infants look longer at the face of a person who had previously spoken in their native language with a native accent, relative to a second person who previously spoke in a foreign language or accent (Kinzler et al., 2007). Nevertheless, in each of the cases described above depicting infant research, it is not clear whether looking patterns in infancy are reflective of rich social preferences, or instead may reflect perceptual processing advantages, without any obligatory social meaning.

Though children demonstrate preferences for the familiar based on multiple dimensions, children’s early social responses also reflect priorities in the importance they grant to different social categories (Kinzler, Shutts, & Correll, 2010). Children show social preferences for same-gender children by two to three years of age (e.g., LaFreniere, Strayer, & Gauthier, 1984; Jacklin & Maccoby, 1978); nevertheless, race-based preferences do not reliably emerge until closer to 4 or 5 years of age (Abel & Sahinkaya, 1962; Aboud, 2003; Brown & Johnson, 1971; Kircher & Furby, 1971; Stevenson & Stewart, 1958). In a recent study, Shutts, Banaji, & Spelke (2010) directly compared the influence of gender, race and age on 3-year-old children’s preferences for novel objects or activities that were endorsed by unfamiliar people who varied in gender, race and age. Gender and age, but not race, were robust guides to children’s choices. Similarly, 5-year-old children express beliefs that gender categories, but not race categories, are objectively and biologically determined (Rhodes & Gelman, 2009). Finally, though children demonstrate both native-accent and own-race preferences when tested in isolation (Aboud, 1988; Kinzler et al., 2007), when the two categories are put in conflict such that accent is pitted against race, children prefer native-accented other-race individuals to foreign-accented own-race individuals (Kinzler, Shutts, DeJesus, & Spelke, 2009). To tease apart the forces that drive children’s developing social preferences and potential priorities that emerge in children’s social categorization, it will be important to study the emergence of these preferences in younger infants.

Do infants develop meaningful social preferences among novel individuals? If so, do these preferences depend on the relative familiarity of those individuals on any dimension, or do they depend on a more specific focus on particular kinds of categorical information? Recent research begins to address this question by focusing on infants’ social engagement with speakers of different languages and accents. In a series of studies, 10-month-old infants in the U.S. and France were shown movies of a native French speaker and a native English speaker who spoke to the infant in alternation. Infants then were shown events in which the two speakers appeared together without speaking, held up two identical toys and, silently and in synchrony, offered the toys to the infant. Just at the moment at which the toys disappeared from view, two real toys appeared in front of the infant, giving the illusion that the toys came from the screen. Infants in the U.S. reached for the toy offered by an English speaker rather than a French speaker, and infants in France reached for the toy offered by the French speaker, even though the toys were identical and were never paired on screen with the language (Kinzler et al., 2007). Prior to speaking themselves, therefore, infants chose to interact with a native speaker of their native language.

Further research provides evidence that social preferences for native speakers persist in later childhood and guide even more explicit social decisions. In one study, 2.5-year-old children were shown the same displays of French and English speakers. The two speakers then appeared together silently, and children were given an opportunity to “give a present” to one of them. Children in both the U.S. and France reliably chose the native speaker as the recipient of their gift (Kinzler, Dupoux, & Spelke, under review). In another study, 5-year-old children were shown still photographs of children and then listened to samples of their speech, which varied either in language or in accent, and were asked to choose one child as a friend. Children’s choices were reliably affected by the accent with which the other children spoke. Moreover, children’s friendship choices dissociated from their judgments of comprehensibility: although children understood a child who spoke their native language with a foreign accent, they nonetheless preferred to associate with a native-accented child (Kinzler et al., 2009).

The above studies provide tools that can be used to probe the origins and nature of social categories, and find signatures of social preferences that go beyond measures of looking time in infancy. Beyond its potential evolutionary significance, language might be considered a particularly good candidate for eliciting social preferences early in development. From birth, infants prefer the sound of their native language to a foreign language, and discriminate two foreign languages if they cross a rhythmic boundary (Mehler, Jusczyk, Lambertz, Halsted, Bertoncini, & Amiel-Tison, 1988; Nazzi, Bertoncini, & Mehler, 1998; Weikum, Vouloumanos, Navarra, Soto-Faraco, Sebastián-Gallés, & Werker, 2007). By 5 months of age, infants successfully discriminate two languages or dialects within the same rhythmic class, provided that one of the languages is their own (Bosch & Sebastián-Gallés, 1997; Nazzi, Jusczyk & Johnson, 2000). Beyond the literal communications it provides, spoken language also offers information about individuals’ nationality, regional membership, ethnic group, and social status or class (Labov, 2006). Indeed, adults use the language and accent of individuals that they have never met to infer not just the origins of those individuals, but also their intelligence, warmth, and even height (see Giles & Billings, 2004 for a review).

Language, however, is not alone in marking social groups in modern times. Language and race are similar in dividing the human social world into groups with high intra-group and low inter-group contact. Both categories elicit looking preferences for the familiar in infants (Bar-Haim et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2005; Kinzler et al., 2007), and within the first year of life infants evidence better face recognition of familiar compared to unfamiliar-race faces (Kelly, Quinn, Slater, Lee, Ge, & Pascalis, 2007; Sangrigoli & de Schonen, 2004). By the end of the preschool years, children reliably express race-based social preferences and inferences (e.g., Aboud, 1988; Baron & Banaji, 2006; Cameron, Alvarez, Ruble, & Fuligni, 2001). And, research from social psychology has provided manifest evidence of fast, automatic, and effortless encoding of race as part of person perception in adulthood, with myriad cognitive and social consequences (e.g., Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2002; Hodson, Dovidio, & Gaertner, 2002; Ito & Urland, 2003; Macrae & Bodenhausen, 2000; Meissner & Brigham, 2001; Pettigrew & Meertens, 1995). Thus, if the development of social preferences stems from differences observed in any dimension of social familiarity that infants can perceptually discriminate, or from social group distinctions that are marked in adulthood in modern times, then majority-race infants and young children should show social preferences based not only on language, but also on race. In contrast, if infants’ earliest social preferences rely in part on attention to factors that distinguished groups throughout evolutionary history, then infants may not award the same social importance to race as they do language.

In the present research, we borrow methods previously used to test social preferences based on language, and employ them to test for early social preferences based on race. Three measures that previously revealed infants’ and children’s social preferences based on language were used to test the emergence of race-based social preferences throughout early childhood: toy choices at 10 months (Kinzler et al., 2007), toy giving at 2.5 years (Kinzler et al., under review), and explicit judgments at 5 years (Kinzler et al., 2009). In all three of the studies presented here, children were shown the same videotaped events involving one Black and one White female who smiled and, in some conditions, spoke with the child’s native language and accent.

The present studies tested the race-based social preferences only of majority-race, White infants. We did not test minority-race infants, because the familiarity theory of social preferences makes no clear predictions concerning the preferences of such infants, for whom faces of both races are likely to be highly familiar (Bar-Haim et al., 2006; see also Aboud & Skerry, 1984). Moreover, although past research has shown preferences for native language speakers in infants for whom the native language is also the country’s predominant language (e.g. English in the U.S. and French in France), we do not know if the same preferences would be shown by infants whose families speak a minority language. To maximize the similarity of the present tests of race preferences to previous tests of language preferences, therefore, we focused only on infants of the majority race (White) in their communities.

Experiment 1 presented White 10-month-old infants with an interactive “toy choice” in which toys were offered to infants by individuals who were either their own race (White), or another race (Black), and infants’ choices were measured. Experiment 2 used the same displays to test 2.5-year-old children’s selective giving of toys to own-race vs. other-race individuals. Experiment 3 presented White 5-year-old children with the same test displays as shown to infants and toddlers, and assessed children’s explicit social preferences towards own- and other-race individuals.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 borrowed the method of Kinzler et al. (2007), which tested infants’ early social preferences based on language, to assess infants’ preferences for social interactions based on race. White 10-month-old infants were presented with videos of a White and a Black individual who each offered identical toy objects to the infant. An illusion was created such that the toys appeared to emerge from the screen, and landed on the table in front of the infant. Infants’ manual choices of objects were measured.

Because past research using this method revealed a strong effect of native language on infants’ toy choices, it was important to equate the speech of the two individuals. Nevertheless, a question arises as to whether to present the individuals in a speech context. It is possible that the presence of language in these videotapes would enhance any social effect of race, because the opportunity to hear both people speak might heighten infants’ attention to the people and their contrasting properties. Alternatively, given that speech may provide infants with evidence that each speaker is a member of their native community, social preferences between individuals of different races may be stronger when the individuals are silent and their language status is ambiguous. Accordingly, half of the infants in this experiment were tested with individuals who were silent (but friendly) throughout the study, and the remaining infants were tested with individuals who both spoke to infants in their native language.

Method

Participants

24 full-term White 10-month-old infants participated in the study (14 females; mean age 10 months 13 days; range 9 months 23 days to 11 months 2 days). Data from 1 additional subject were excluded due to failure to make a choice on any trial.

Materials

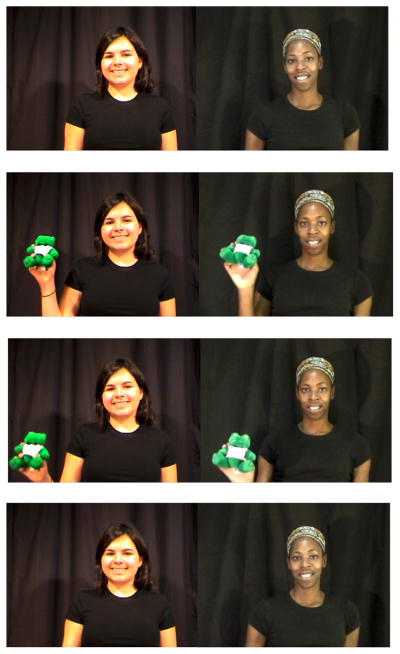

The stimuli were modeled after those from Kinzler et al. (2007). The toy choice films depicted the two speakers (one White female, one Black female) simultaneously on screen, each holding an identical toy animal, smiling at the toy, and then smiling at the infant and lowering the toy as if offering it to the infant (19s; Figure 1). The White actress was featured in Kinzler et al. (2007). The Black actress was identified by adult raters to be clearly of African descent. The films were projected approximately life-size on a screen that measured 92×122cm, behind a 50cm table. The speaking trials consisted of each individual speaking to the baby in native child-directed speech for 10 seconds (in a 13-total second film).

Figure 1.

Images of the White and Black actresses in Experiment 1. These same individuals were featured in all 3 experiments.

Design and Procedure

On each of 4 test trials, infants saw a toy choice event, with both White and Black individuals pictured simultaneously offering a toy to the infant. Just at the moment at which the toys disappeared off screen, two real toys “magically” appeared from behind the table for the infant to grasp, giving the illusion that they emerged from the screen. The objects were attached by Velcro to PVC piping that rotated from behind the table, and landed on the table equidistant from the infant and in front of the silent and motionless images of the two individuals. Half of participants saw only these 4 toy choice events; half of participants saw each toy offering event preceded by speaking trials, in which each individual engaged in infant-directed native speech. The ordering and lateral positions of the White and Black individuals were counterbalanced across infants in each condition, and the individuals reversed sides after the second trial. Infants’ first reach during a 15-second period was recorded by a observer who was blind to the lateral position of individuals on each trial. Data for any infant who reached on at least 1 of the 4 trials, and watched the relevant offering event, were included. Data were analyzed by a repeated-measures ANOVA comparing number of choices of the toy offered by the White and Black individual.

Results

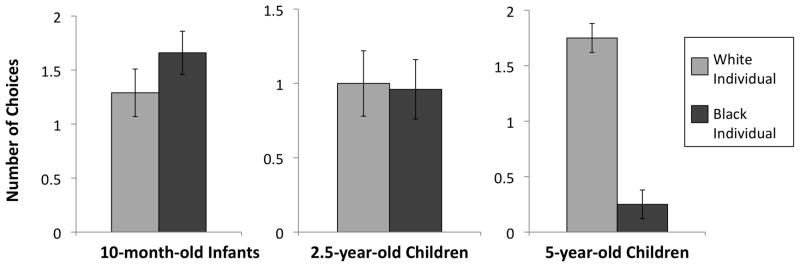

In both the speaking and the silent conditions, infants accepted toys about equally from the individuals of the two races; if anything, they showed a slight preference for the Black individual (Figure 2, left). A repeated-measures ANOVA comparing number of choices for the toy offered by the White individual vs. number of choices for the toy offered by the Black individual as a within-subjects variable, and condition (speaking or silent) as a between-subject variable revealed that infants had no significant preference to accept a toy from the White or Black individual (MWhite=1.29, SE=.22; MBlack=1.66; SE=.20, F(1, 22)=1.23, p=n.s.), with no main effect of condition (F(1,23)=.253, p=n.s.), and no interaction of race with condition (F(1, 22)=1.23, p=n.s.). A binomial non-parametric test confirmed this result: 11 children took more toys from the Black individuals, 6 children took more toys from the White individual, and 7 children took toys equally (p=n.s., 2-tailed sign test)

Figure 2.

Number of trials on which infants and children chose the White or Black individual in Experiment 1 (left), 2 (center) and 3(right). Error bars represent standard error.

Discussion

In contrast to infants’ preferences for interactions based on language (Kinzler et al., 2007), infants did not preferentially accept toys from own-race individuals. Although young infants’ looking patterns in previous research provide evidence of attention to race (Bar-Haim et al., 2006; Kelley et al., 2005), the present finding suggests that early looking patterns may not necessarily reflect deeper social predilections that are present prior to an infant’s first birthday. Looking preferences may evidence low-level visual preferences for familiar faces that are not consistent with social discriminations. Relative familiarity of any ilk, thus, may not equally compel early preferences for social interactions as measured on this task.

It should be noted that 10 months of age just precedes the time when infants are beginning to speak. Perhaps the nature of early language learning places a great emphasis on attention to native speakers, and slightly older, more linguistically sophisticated children would attend to both language and race in guiding their social preferences. Moreover, given that race-based social preferences are shown to emerge during the preschool years (e.g. Aboud, 1988), it is plausible that such preferences might be found by the end of toddlerhood. Experiment 2 therefore tested 2.5-year-old children’s social giving, which has been shown in past work to be an age-appropriate measure of social preferences in toddlers for native, compared to foreign speakers.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 investigated toddlers’ preferences for own- vs. other-race individuals by means of a “magical giving game,” (after Kinzler et al., under review). Children were given an object described as a “present” and were shown that they could place it in a box to give to one of two cartoon characters, as training. When they did so, the toy subsequently appeared on screen in front of the character whose box the child had chosen. Once children understood the game, the characters were replaced by images from the videotapes used in Experiment 1, depicting two women of differing race. Children’s choices of giving to either the White or Black individual were recorded.

Method

Participants

24 full-term 2.5-3-year-old White children participated in the study (12 females; mean age 32.5 months; range 29.5 – 35.5 months).

Materials

The same Black and White individuals featured in Experiment 1 served as stimuli. Static images of the two individuals were projected approximately life-size on screen, with the child seated at the table in front of the screen. A table was positioned 50cm from the screen, to allow for an experimenter to move between the screen and the table. On the table were two cardboard boxes (20cm3) with a felt opening on top, and a felt opening on the side towards the screen, such that a child could place something in the box on the top side, and an experimenter could remove the item from the back of the box. Boxes were placed on the left and right side of the table, equidistant from the child.

Procedure

Children were first instructed in the giving game. An experimenter sat facing the child, between the screen and the table. A series of pairs of cartoon animals appeared on the left and right side of the screen, and children were shown that when a “present” (different colored toy balls) was placed in one of the two boxes, the present would subsequently appear on screen, and reward the animal on the corresponding side of the screen. During 2 test trials, children were shown an image of the two individuals side-by-side on screen, at which point children were instructed to “give a present” to one of the two individuals. When the child placed the present in one of the two boxes, a chime noise then was played, the present appeared on the screen, and the individual on the corresponding side of the screen smiled. Lateral position of presentation (White individual on the left or right), was counterbalanced across children.

Results and Discussion

Children gave presents equally to the two individuals who differed in racial group membership (MWhite=1.00, SE=.12; MBlack=.96, S.E.=.11; Figure 2, center). A non-parametric test confirmed that children did not selectively give to one individual over the other: 4 children gave more to the White individual, 4 children gave more to the Black individual, and 16 children gave equally (p=n.s., 2-tailed sign test). To test whether children’s performance reflected a strategy of equal giving across the two trials, a further analysis focused on just the first trial, when children had no way to know whether a second trial would be offered. On the first trial, 11 children chose to give the present to the White individual,12 children chose the Black individual, and 1 child did not make a choice. Again, their patterns of response on the first trial did not differ from chance (p=n.s., 2-tailed sign test). Thus, the absence of race-based giving preferences cannot be explained as a strategy of egalitarian giving. The findings suggest, instead, that 2.5-year-old children’s giving is influenced by the language of their potential recipients but not by the recipients’ race.

Although past research demonstrates clear evidence of majority race preschool-aged children’s social preferences based on race, most findings are reported beginning at age 4 or 5, and do not necessarily find similarly strong results with 3-year-old children (Abel & Sahinkaya, 1962; Aboud, 2003; Brown & Johnson, 1971; Stevenson & Stewart, 1958; Kircher & Furby, 1971). Recent research investigating 3-year-old children’s attention to social categories in guiding their object-based preferences finds that children of this age only marginally attend to race, in contrast to robust attention to gender and age (Shutts, Banaji, & Spelke, 2010). Thus, a failure to find race-based social preferences at 2.5 years is not inconsistent with previous research, and provides further evidence that race-based social preferences may emerge only by the end of the preschool years.

It should be noted that children tested in this sample, as well as in Experiment 1, were exclusively White. Though testing a more diverse group of children would certainly be desirable, if one were to expect to find early race-based preferences, they would most likely be found in White majority-race children (Aboud & Skerry, 1984). The final experiment therefore tested for race-based social preferences in older White children, using the same stimuli presented to infants and toddlers in the first 2 experiments.

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 investigated 5–6 year old children’s explicit social preferences for novel individuals who are Black vs. White, using two measures. Children were shown the displays presented to infants and younger children in Experiments 1 and 2, they were told that these displays were shown to infants, and they were asked which person they thought that infants would prefer, and also which person they would prefer to have as a friend, following the method of Kinzler et al. (2009). Consistent with past research, we predicted that children would select the White individual.

Participants

12 White 5–6-year-old children (mean: 5 years 9 months; range: 5 years, 2 months to 7 years 0 years) participated in the experiment.

Materials

Images from dependent measures in Experiments 1 (toy offering events) and 2 (static images of each individual) served as stimuli.

Design and Procedure

Children were shown two events. During the toy offering event, children were shown a movie of the White and Black individual smiling, and offering two toys. Children were asked, “These are movies we show to babies. Whom do you think babies will choose to take toys from?” During the static event, children were shown the Black and White individual on screen, and were asked “Which one would you rather be friends with?” The order of the offering and static trials, the order of individuals presented within each trial, and the left-right positions of the two individuals presented on the screen were orthogonally counterbalanced across children. Children’s choices were tested against chance (.5) by binomial tests.

Results and Discussion

Across the two test questions, children robustly chose the White individual (MWhite=1.75 choices, SE=.13; MBlack=.25 choices, S.E.=.13). See Figure 2, right. When shown the toy offering event, 11/12 children chose the White individual (p < .01, 2-tailed sign test). When shown the static images and asked whom they preferred as friends, 10/12 children chose the White individual (p < .05, 2-tailed sign test). Thus, consistent with past research, kindergarten-aged children demonstrated race-based social preferences. Moreover, children’s choices for the own-race individual provide evidence that the race of the particular individuals used in these studies was apparent, and infants’ and children’s failure to demonstrate race-based social preferences in Experiments 1 and 2 was not due to an unbalanced choice of stimuli.

General Discussion

Across three experiments, a developmental progression in infants’ and children’s race-based social preferences was observed. In Experiment 1, White 10-month-old infants accepted toys equally from White and Black individuals. In Experiment 2, White 2.5-year-old children gave toys equally to White and Black individuals. In contrast, when White 5–6-year-old children viewed the same events, they expressed race-based social preferences. These findings cast doubt on the thesis that the same-race looking preferences of younger, majority-race infants are true social preferences. Rather, they suggest that social preferences based on race emerge between 2.5 and 5 years of age.

Several alternative interpretations for the present findings can be rejected, based on the findings themselves and on past research. First, it is unlikely that the absence of race-based preferences at the two younger ages reflects an egalitarian bias leading children to choose the two people equally across trials, masking an existing race-based preference. Although egalitarian responding is sometimes observed in children, it tends to increase, not decrease, with age (Fehr, Bernhard, & Rockenbach, 2008). Moreover, children showed no egalitarian bias towards giving resources to individuals who differ in their native language (Kinzler et al., 2007, in review). Finally, in Experiment 2, children showed no preference overall for the own-race individual, and no preference on the first of two giving trials. All these findings cast doubt on the idea that infants and children have an own-race preference that is tempered by a tendency toward egalitarian social behavior.

Second, it is unlikely that infants’ and young children’s equal patterns of receiving and giving reflect a failure to detect the individuals’ race. Children’s choices for the own-race individual in Experiment 3 provide evidence that the race of the particular individuals used in these studies was apparent to older children. Moreover, race detection is highly reliable and replicable in even younger infants than those tested here (Bar Haim et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2005). Indeed, 3-month-old infants respond to race in faces that are presented under far more impoverished conditions, when each face is presented only in a single static photograph. Although abilities to discriminate and categorize faces likely increase substantially over infancy and childhood – as suggested by an increase over the first year of life in infants’ relative recognition memory for familiar-race, over unfamiliar-race faces (Kelly et al., 2007) – the present findings are not likely due to a simple failure of perceptual discrimination.

Third, it is unlikely that infants’ and young children’s equal patterns of receiving and giving reflect limitations of the methods used to test for race-based social preferences. Experiments 1 and 2 tested for these preferences using the same methods that provided evidence for social preferences based on language, in infants and children of the same age as those in the present studies (Kinzler et al., 2007; Kinzler et al., in review). Of course, it is always possible that infants and young children have some incipient social preferences among people of different races that the present displays and methods failed to reveal. If such preferences exist, however, they are fragile in comparison to infants’ preferences among speakers of different languages.

The contrasting effects of language and race on infants’ social preferences are of theoretical importance, for they suggest that these two dimensions of familiarity are not equal to infants. Although young infants look longer at both individuals who previously spoke in a native language with a native accent (Kinzler et al., 2007), and who are of a familiar race (Bar-Haim et al., 2006; Kelly et al., 2005), early looking preferences based on language and race may reflect two different phenomena. The former may be a sign of a social preference for individuals in one’s native language group. In contrast, the latter may be a sign of visual familiarity, allowing for more efficient or deeper perceptual processing of a face with little or no consequence for early social interactions. It would be interesting to further explore potential relationships and discontinuities between infants’ and children’s face processing and social preferences.

Although 5–6 year old children showed preferences based on race in Experiment 3, other research has compared race and language preferences directly at this age, providing evidence that accent trumps race in children’s explicit social judgments (Kinzler et al., 2009). Though by 5 years of age children profess explicit preferences for both native-accented individuals and own-race individuals in isolation, when accent is pitted against race, White children prefer to be friends with someone who is Black and speaks in a native accent, rather than someone who is White and speaks with a foreign accent (Kinzler et al., 2009). Throughout the preschool years, therefore, language provides a more powerful basis for social categorization and preference than does race.

There are several reasons why language may trump race in its early social salience. First, children have a “head start” in their familiarization to language over race. From birth, infants prefer the sound of their native language due to input they received in the womb (Mehler et al., 1988; Moon, Cooper, & Fifer, 1993), whereas it is not until 3 months of age that infants prefer own-race faces (Kelley et al., 2005). Furthermore, as discussed above, there is reason to think that the language with which people speak may have carried greater weight in denoting group membership throughout our evolutionary history than did skin color. Though neighboring groups in ancient times likely spoke with different accents and dialects, they likely didn’t look very different in terms of their race (Baker, 2001; Kurzban, Tooby, & Cosmides, 2001). Thus, cognitive evolution may have favored attention to language over race in denoting coalitional group membership, and this predisposition may be reflected in modern-day infants’ early social preferences.

Finally, and perhaps most speculatively, attention to language over race may reflect an “essentialist bias,” in which language is treated by children as an “inner” property, whereas race is treated as a less important “outer” property of individuals. This hypothesis accords with research showing that children’s attention to categorical information can outweigh attention to perceptual information when reasoning about other social categories such as gender and ethnicity (Gelman, Collman, & Maccoby, 1986; Diesendruck & haLevi, 2006), and that even in infancy, children see internal features of an individual as being more predictive of his behaviors than external properties (Newman, Herrmann, Wynn, & Keil, 2008). These explanations are not inconsistent with one another, and may in fact work together to explain the phenomena at hand. In particular, an essentialist bias may be a proximate mechanism that mediates the ultimate adaptive mechanism for monitoring meaningful social groups.

The present research raises questions about the potential malleability of early social biases. Infants and toddlers in Experiments 1 and 2 do not attend to race in guiding their early interactions, but 5-year-old children shown the same stimuli prefer individuals of their own race almost unanimously. The finding that race-based preferences emerge over childhood suggests that they may not be mandatory, but rather may emerge as a result of exposure to racially stratified societies in which race is often a marker of group membership. Children may be inclined to group the world into human kinds (Hirschfeld, 1996), or ingroups and outgroups (Dunham, Baron, & Banaji, 2008); nonetheless, children may not view race as a mandatory variable by which groups are determined in all environments. Future research therefore should investigate the potential malleability of early social preferences as a result of exposure to diverse environments. The present research provides a note of optimism that later race-based social preferences may not be a predetermined outcome of any and all social worlds.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abel H, Sahinkaya R. Emergence of sex and race friendship preferences. Child Development. 1962;33:939–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE. Children and Prejudice. New York: Blackwell; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE. The formation of in-group favoritism and out-group prejudice in young children: Are they distinct attitudes? Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:48–60. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE, Skerry SA. The development of ethnic attitudes. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1984;15:3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GM, Hines M. Gender labels and play styles: Their relative contribution to children’s selection of playmates. Child Development. 1994;65:869–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboud FE. Children and Prejudice. New York: Blackwell; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Baker MC. The atoms of language: The mind’s hidden rules of grammar. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Ziv T, Lamy D, Hodes R. Nature and nurture in own-race face processing. Psychological Science. 2006;17:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron AS, Banaji MR. The development of implicit attitudes: Evidence of race evaluations from ages, 6, 10, and adulthood. Psychological Science. 2006;17:53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein RF. Exposure and affect: Overview and meta-analysis of research, 1968–1987. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;106:265–289. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch L, Sebastián-Gallés N. Native-language recognition abilities in 4-month-old infants from monolingual and bilingual environments. Cognition. 1997;65:33–69. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(97)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G, Johnson SP. The attribution of behavioral connotations to shaded and white figures by Caucasian children. British Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology. 1971;10:306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JA, Alvarez JM, Ruble DN, Fuligni AJ. Children’s lay theories about ingroups and outgroups: Reconceptualizing research on prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2001;5:118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cosmides L, Tooby J, Kurzban R. Perceptions of race. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2003;7:173–178. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(03)00057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diesendruck G, haLevi H. The role of language, appearance, and culture in children’s social category-based induction. Child Development. 2006;77:539–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Kawakami K, Gaertner SL. Implicit and explicit prejudice and interracial interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:62–68. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunham Y, Baron AS, Banaji MR. The development of implicit intergroup cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2008;12:248–253. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST. Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The handbook of social psychology: Vols. 1 and 2. 4. 1998. pp. 357–411. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Bernhard H, Rockenbach B. Egalitarianism in young children. Nature. 2008;454:1079–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature07155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DC. Children’s knowledge of the social functions of younger, older, and same-age peers. Child Development. 1984;55:1429–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Giles H, Billings AC. Assessing language attitudes: Speaker evaluation studies. In: Davies A, Elder C, editors. The Handbook of Applied Linguistics. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. pp. 187–209. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman S, Collman P, Maccoby E. Inferring properties from categories versus inferring categories from properties: The case of gender. Child Development. 1986;57:396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Gluszek A, Dovidio JF. The way they speak: A social psychological perspective on the stigma of nonnative accents in communication. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2010;14:214–237. doi: 10.1177/1088868309359288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison AA. Exposure and popularity. Journal of Personality. 1969;37:359–377. [Google Scholar]

- Hodson G, Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL. Processes in racial discrimination: Differential weighting of conflicting information. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2002;28:460–471. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfeld L. Race in the making: Cognition, culture, and the child’s construction of human kinds. Cambridge, MA, US: The MIT Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ito TA, Urland GR. Race and gender on the brain: Electrocortical measures of attention to the race and gender of multiply categorizable individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:616–626. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacklin CN, Maccoby EE. Social behavior at 33 months in same-sex and mixed-sex dyads. Child Development. 1978;49:557–569. [Google Scholar]

- Katz P, Kofkin J. Race, gender, and young children. In: Luthar SS, Burack JA, Cicchetti D, Weisz J, editors. Developmental Psychopathology: Perspectives on Adjustment, Risk, and Disorder. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly D, Quinn P, Slater A, Lee K, Gibson A, Smith M, et al. Three-month-olds, but not newborns, prefer own-race faces. Developmental Science. 2005;8:F31–F36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2005.0434a.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly DJ, Quinn PC, Slater AM, Lee K, Ge L, Pascalis O. The other-race effect develops during infancy: Evidence of perceptual narrowing. Psychological Science. 2007;18:1084–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Dupoux E, Spelke ES. The native language of social cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:12577–12580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705345104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Dupoux E, Spelke ES. “Native” objects and collaborators: infants’ object choices and acts of giving reflect favor for native over foreign speakers. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2011.567200. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Shutts K, Correll J. Priorities in social categories. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2010;40:581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Kinzler KD, Shutts K, DeJesus J, Spelke ES. Accent trumps race in guiding children’s social preferences. Social Cognition. 2009;27:623–634. doi: 10.1521/soco.2009.27.4.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher M, Furby L. Racial preferences in young children. Child Development. 1971;42:2076–2078. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski K, Lo Y. The influence of perceptual features, ethnic labels, and sociocultural information on the development of ethnic/racial bias in young children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2001;32:444–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzban R, Tooby J, Cosmides L. Can race be erased? Coalitional computation and social categorization. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:15387–15392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251541498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labov W. The Social Stratification of English in New York City, Second Edition. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- LaFreniere P, Strayer F, Gauthier R. The emergence of same-sex affiliative preferences among preschool peers: A developmental/ethological perspective. Child Development. 1984;55:1958–1965. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman D, Oum R, Kurzban R. The family of fundamental social categories includes kinship: Evidence from the memory confusion paradigm. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;38:998–1012. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby E, Jacklin C. Gender segregation in childhood. In: Reese HW, editor. Advances in child development and behavior. Vol. 20. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1987. pp. 239–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae CN, Bodenhausen GV. Social cognition: Thinking categorically about others. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:93–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehler J, Jusczyk P, Lambertz G, Halsted N, Bertoncini J, Amiel-Tison C. A precursor of language acquisition in young infants. Cognition. 1988;29:143–178. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(88)90035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner CA, Brigham JC. Thirty years of investigating the own-race bias in memory for faces: A meta-analytic review. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2001;7:3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Moon C, Cooper RP, Fifer WP. Two-day-olds prefer their native language. Infant Behavior & Development. 1993;16:495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Nazzi T, Bertoncini J, Mehler J. Language discrimination by newborns: Toward an understanding of the role of rhythm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 1998;24:756–766. doi: 10.1037//0096-1523.24.3.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazzi T, Jusczyk PW, Johnson EK. Language discrimination by English-learning 5-month-olds: Effects of rhythm and familiarity. Journal of Memory and Language. 2000;43:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Newman GE, Herrmann P, Wynn K, Keil FC. Biases towards internal features in infants’ reasoning about objects. Cognition. 2008;107:420–432. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Spelke ES. Foundations of cooperation in young children. Cognition. 2008;108:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF, Meertens RW. Subtle and blatant prejudice in western Europe. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1995;25:57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pietraszewski D, Schwartz A. Is accent a dedicated dimension of agent representation?. Paper presented at the Human Behavior and Evolution Society; Williamsburg, VA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn P, Yahr J, Kuhn A, Slater A, Pascalis O. Representation of the gender of human faces by infants: A preference for female. Perception. 2002;31:1109–1121. doi: 10.1068/p3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn PC, Uttley L, Lee K, Gibson A, Smith M, Slater AM, Pascalis O. Infant preference for female faces occurs for same- but not other-race faces. Journal of Neuropsychology. 2008;2:15–26. doi: 10.1348/174866407x231029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey-Rennels JL, Langlois JH. Infants’ differential processing of female and male faces. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:59–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, Brickman D, Gelman SA. Children’s concepts of race and social alliances under review. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes M, Gelman SA. A developmental examination of the conceptual structure of animal, artifact, and human social categories across two cultural contexts. Cognitive Psychology. 2009;59:244–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes G, Halberstadt J, Brajkovich G. Generalization of mere exposure effects to averaged composite faces. Social Cognition. 2001;19:57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sangrigoli S, de Schonen S. Recognition of own-race and other-race faces by three-month-old infants. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:1219–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutts K, Banaji MR, Spelke ES. Social categories guide young children’s preferences for novel objects. Developmental Science. 13:599–610. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00913.x. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HW, Stewart EC. A developmental study of racial awareness in young children. Child Development. 1958;29:399–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1958.tb04896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weikum WM, Vouloumanos A, Navarra J, Soto-Faraco S, Sebastián-Gallés N, Werker JF. Visual language discrimination in infancy. Science. 2007;316:1159. doi: 10.1126/science.1137686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc RB. Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1968;9:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc RB. Mere exposure: A gateway to the subliminal. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:224–228. [Google Scholar]