Synopsis

Lung retransplantation comprises a small proportion of lung transplants performed throughout the world, but has become more frequent in recent years. The selection criteria for lung retransplantation are similar to those for initial lung transplant. Survival after lung retransplantation has improved over time, but still lags behind that of initial lung transplantation. These differences in outcome may be attributable to medical comorbidities. Lung retransplantation appears to be ethically justified, however the optimal approach to lung allocation for retransplantation needs to be defined.

Keywords: lung transplantation, retransplantation

Lung transplantation is a therapeutic option for patients with advanced lung disease. Early or late graft failure or airway compromise may lead to significant morbidity and mortality after lung transplantation. While there are no curative medical or surgical interventions for many of these complications, lung retransplantation is one potential therapy. Retransplantation raises many of the same considerations faced in initial transplantation in terms of indications, selection of candidates, surgical approach, and outcomes, but is complicated by short- or long-term intensive immunosuppression, infection, and technical issues attributable to the previous transplant. Perhaps the most important (and controversial) aspect of retransplantation is whether allocating a second (or third)[1] lung allograft to one patient while potentially depriving another patient of an initial transplant is ethically justifiable.

Until recently, the issues surrounding lung retransplantation were more theoretical than real since so few were performed. However, changes in the method of lung allocation in the US have increased the frequency of retransplantation and brought many of these controversies to bear on lung transplant allocation committees and transplant centers. Unfortunately, there is no consensus regarding the medically and ethically appropriate retransplant candidate.

Frequency of Lung Retransplantation

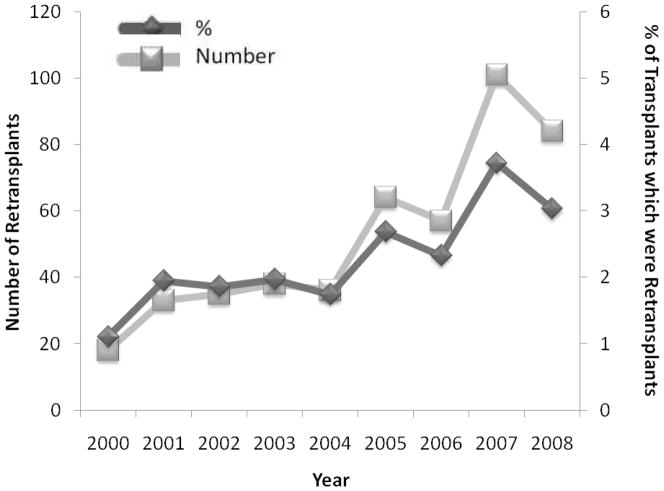

Four hundred and sixty-six of the 19,524 (2.4 %) transplants performed from 2000 to 2008 and reported to the ISHLT Registry were retransplants [2]. There has been a statistically significant increase in the number and percentage of lung transplants that were retransplants performed over the years 2000 to 2008 (both p ≤ 0.003) (Figure 1). During the years 2000 to 2004, 40 or fewer retransplants were performed yearly, while 60–110 were performed yearly between 2005 and 2008. Similarly, less than 2% of all lung transplants in the ISHLT Registry were retransplants between 2000 and 2004, whereas 2–4% of transplants were retransplants between 2005 and 2008. Both the mean yearly number of retransplants (77 vs. 32) and the mean yearly proportion of lung transplants that were retransplants (2.9% vs. 1.7%) were significantly greater for the years 2005 to 2008 than for the years 2000 to 2004 (both p = 0.01).

Figure 1.

Adult lung retransplants performed (number and % of transplants) by year from 2000 to 2008 in the ISHLT Registry (p = 0.001 and p = 0.003 for associations between number and % with time). Data from Christie JD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-seventh official adult lung and heart-lung transplant report--2010. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(10):1104–1118.

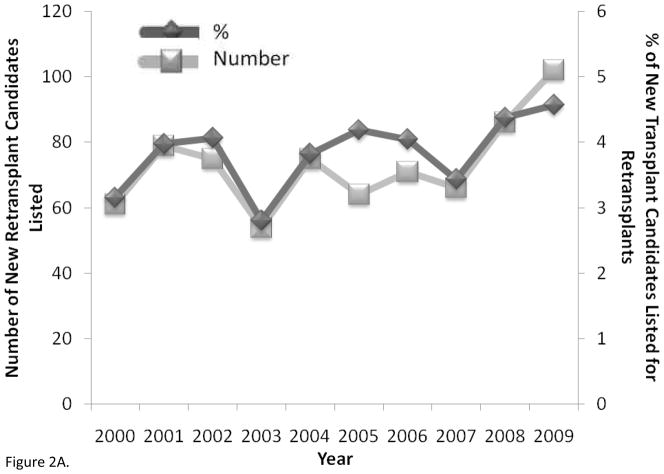

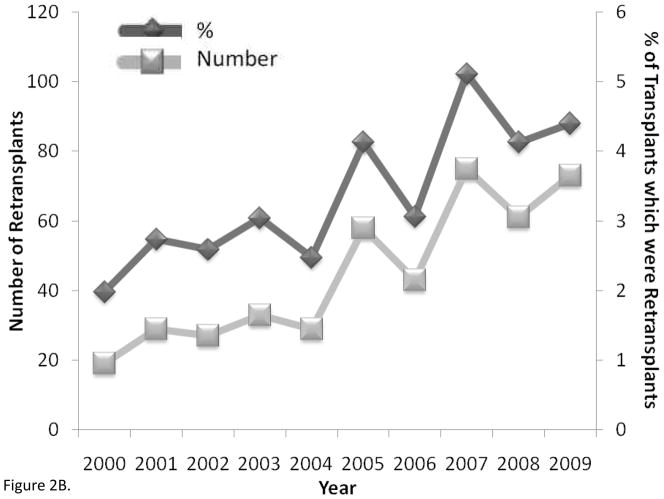

Lung retransplantation has become more common particularly in the US [3]. The number of new retransplant candidates and the proportion of new transplant candidates who were retransplant candidates added to the waiting list each year were unchanged over the years 2000 to 2009 (both p = 0.10) (Figure 2A). There were no differences in the mean yearly number of patients listed for retransplantation between 2005 and 2009 compared to those listed between 2000 and 2004 (78 vs. 69 respectively, p = 0.46), however there may have been a slight increase in the mean yearly proportion of newly listed patients who were retransplant candidates in 2005 to 2009 compared to 2000 to 2004, but this was not statistically significant (4.1% vs. 3.6% respectively, p = 0.08). Despite the stability in the rates of listing for retransplantation, both the absolute number of retransplants performed and the percentage of transplants that were retransplants significantly increased between 2000 and 2009 (both p ≤ 0.003) (Figure 2B). The mean yearly number of retransplants (62 vs. 27) and the mean yearly proportion of lung transplants that were retransplants (4.2% vs. 2.6%) were significantly greater for the years 2005 to 2008 than for the years 2000 to 2004 (both p = 0.01)

Figure 2.

A) Adult lung retransplantation candidates newly listed (number and % of candidates) (p = 0.10 for associations between number and % with time) and B) adult lung retransplants performed (number and % of total transplants) by year from 2000 to 2009 in the United States (p < 0.001 and p = 0.003 for associations between number and % with time). Data from OPTN as of December 3, 2010, http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov.

These changes in the frequency of lung retransplantation coincided with (and were likely caused by) the introduction of the Lung Allocation Score (LAS) priority system for lung allocation in May 2005 in the US [4]. Before the LAS system, lung allografts were allocated by time accrued on the list (in addition to geography, body size, and blood type). The LAS system prioritizes patients based on calculations of estimated one-year survival with and without lung transplantation, favoring those patients with a combination of high net survival benefit (i.e., the difference between survival with and without transplantation) and high medical urgency (i.e., low estimated survival without transplantation). Because retransplant recipients (specifically with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS)) had one-year wait list survival similar to that of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, they were included in Group D (Restrictive lung diseases) in the LAS calculation and are thereby afforded high priority [4, 5]. Retransplant candidates who would not have remained suitable candidates (or alive) long enough with the previous allocation system can receive a lung offer in a timely fashion under the LAS system. Indeed, the median wait time for retransplantation was much shorter for patients listed under the LAS system than for those listed prior to May 2005 (25 days (interquartile range (IQR), 3–66 days) vs. 180 days (IQR, 32–569 days) respectively, p < 0.001) [6]. Patients listed for retransplantation had median LAS scores within the upper quintile for patients on the active waiting list from 2006 to 2008, explaining the shortened wait times and increase in retransplantation in the US [7].

Selection of Candidates

Lung retransplantation may be indicated for lung transplant recipients with severe lung allograft dysfunction which is not amenable to medical or other surgical therapies. The selection criteria for lung retransplantation are similar to those for initial lung transplantation [8]. Absolute contraindications include recent non-dermatologic malignancy, untreatable advanced disease of another main organ system, non-curable chronic extrapulmonary infection (including chronic active viral hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and human immunodeficiency virus), significant chest wall/spinal deformity, documented medical nonadherence, untreatable psychiatric condition associated with the inability to cooperate or comply with medical therapy, lack of a consistent or reliable social support system, and active or recent substance addiction. Relative contraindications include older age, unstable clinical status, severely limited functional status, colonization with highly resistant or highly virulent bacteria, fungi, or mycobacteria, obesity, severe or symptomatic osteoporosis, mechanical ventilation, and inadequately treated other medical conditions. While there are no defined criteria for when lung transplant recipients should be considered for retransplantation, most patients retransplanted in recent years were one or more years out from their initial transplant (median 3.1 yrs, IQR, 1 – 6.5) [6]. Key factors that affect outcomes after retransplantation include the indication (in terms of type and timing of allograft failure) and the requirement for mechanical ventilation (see below), so that these factors must figure into the decision to evaluate or list someone for retransplantation. The most common indication for both listing and performance of lung retransplantation in the US during the past decade was BOS (Table 1). Twenty percent of retransplants were performed for primary graft dysfunction (PGD) or acute rejection.

Table 1.

Indications for listing and transplanting lung retransplant candidates in the US between 2000 and 2009

| New lung retransplant candidates listed (N = 733) | Lung retransplant recipients (N = 447) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOS | 462 | 63% | 292 | 65% |

| Primary graft dysfunction | 110 | 15% | 77 | 17% |

| Acute rejection | 28 | 4% | 14 | 3% |

| Other | 133 | 18% | 64 | 14% |

Data from OPTN as of December 3, 2010, http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/.

Type of Procedure

There are several operative approaches to the retransplant candidate. Patients who have undergone initial bilateral lung transplant may receive either a single or bilateral lung retransplant [6]. Patients who have undergone initial single lung transplantation may undergo ipsilateral or contralateral single lung retransplantation or a bilateral lung retransplantation.

The decision regarding which type of retransplantation to perform is based on a variety of factors. The presence of suppurative infection in the initial allograft (or remaining native lung) warrants explantation and replacement to prevent early infectious complications in the new allograft(s). Even if not infected, it may still be advantageous to explant the failed allograft which could be a source of ongoing immune stimulation [9], although most recent retransplantation procedures in the US leave the allograft behind while having better outcomes than historical retransplant procedures [6]. Technical issues relating to the choice of single lung transplantation for the initial transplant (contralateral chest wall deformity or pleural disease) might dictate the need for ipsilateral single lung retransplantation. Over time, single:single (ipsilateral) retransplant procedures have become less common and bilateral:single retransplant procedures have become more common, likely reflecting the increasing frequency of initial bilateral lung transplantation [6]. While unadjusted analyses suggest that ipsilateral single lung retransplantation may be associated with a higher risk of death (and contralateral single lung retransplantation associated with a lower risk of death), these findings were not significant predictors of outcome after adjustment for other covariates and were likely confounded by factors such as indication and timing of retransplantation [6].

Outcomes

The risk of death on the waiting list for patients listed for lung retransplantation in the US is double or triple that of patients listed for initial lung transplantation [7]. The mean annual death rate on the list for lung retransplant candidates was 295.6 per 1000 person-years for 2005 to 2008, whereas it was 118.2 per 1000 person-years for all lung transplant candidates.

Only a handful of small studies of the risk factors and outcomes in lung retransplantation have been published. A prospective multicenter registry enrolled 230 retransplant recipients from 47 centers between 1985 and 1996 [10–15]. Twenty-six centers were located in North America, 20 in Europe, and one in Australia. The final publication from this study showed a one-year survival of 47% and three-year survival of 33% [15]. Sixty-three percent of patients were retransplanted for BOS. Patients who were either non-ambulatory or dependent on mechanical ventilation had a significantly increased risk of death. Retransplantation performed before 1992 was also associated with a higher mortality compared to retransplant performed after that date. Patients without these risk factors had outcomes similar to those of patients undergoing initial lung transplantation. While rates of BOS after retransplantation overall were similar to those reported after initial transplantation, those retransplanted < 2 years after their initial transplant had a significantly higher risk of BOS at two years, and those retransplanted for BOS demonstrated a more rapid post-retransplant decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 second than those retransplanted for other indications. The identification of retransplant patients with outcomes similar to those of initial transplant recipients was suggested to justify retransplantation as a viable and ethical option for certain lung transplant recipients with failing allografts. The limitations in this study are its voluntary “registry” design and the historical nature of the data.

Brugiere et al. presented 15 patients who underwent lung retransplantation for BOS at their center between 1988 and 2002 [16]. The one- and five-year survival was 60% and 45% respectively, outcomes similar to those of initial single lung transplantation at the authors’ center. The median time between initial transplantation and retransplantation was 31 months (range, 12–39 months). All were clinically stable at the time of retransplantation, although 40% required tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation and six were not ambulatory. All patients underwent single lung retransplantation (4 ipsilateral, 9 contralateral, and 2 after initial bilateral lung transplantation). The retained allograft was the source of fatal infection in four of the recipients. Such infections related to the allograft always occurred in the presence of suppuration, even though bronchiectasis was minimal or absent at relisting for transplant, leading the authors to propose explantation of the initial allograft whenever possible during retransplantation.

Schafers et al. published a cohort of 14 lung retransplantation patients from their center from 1987 to 1994 [17]. One- and two-year survival was 77% and 64% respectively, which was somewhat lower than initial transplantation at this center. These authors found that pre-operative mechanical ventilation was associated with significantly more days in the intensive care unit (61 d vs. 13 d, p < 0.05) as was early retransplantation (< 90 days from initial transplant) (72 d vs. 16 d, p < 0.05). These factors may also have been associated with higher early mortality. The risk of BOS with retransplantation was also higher than that with initial transplant.

Osaki et al. published a cohort of 17 patients who underwent lung retransplantation (two of whom underwent retransplantation twice) [18]. One- and five-year survival was 59% and 42% respectively, outcomes that were significantly worse than those with initial transplant at their center. The one- and five-year survival rates for the patients retransplanted for BOS (N = 12) were 67% and 44% respectively. The need for mechanical ventilation (or extracorporeal life support) appeared to be associated with an increased risk of death (p = 0.09), however the presence of a retained allograft was not (p = 0.31).

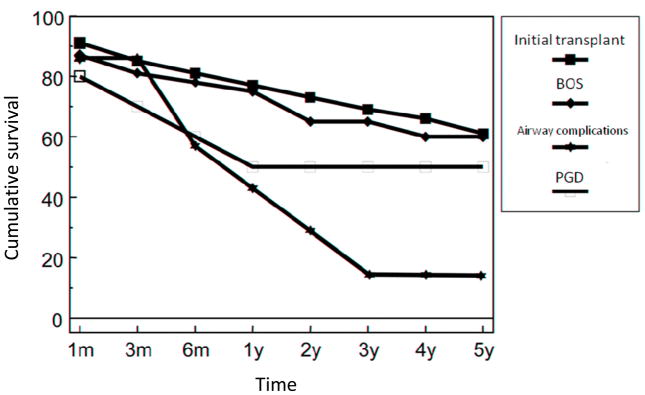

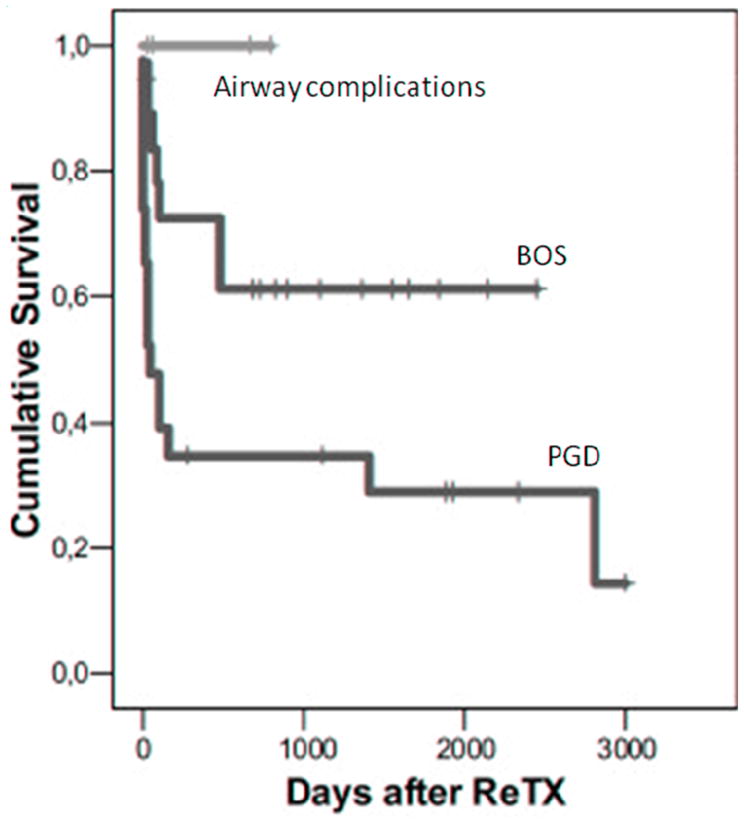

Investigators from the Hannover Thoracic Transplant Program recently published a cohort of 54 consecutive patients who underwent lung retransplantation before January 1, 2004 [19]. Thirty-seven patients were retransplanted for BOS, 10 for PGD, and seven for airway complications (5 with severe dehiscence and 2 with airway scarring). Survival in those patients retransplanted for BOS mirrored that of patients undergoing initial transplantation from this center (Figure 3). However, the patients with PGD and airway complications had a significantly worse survival, leading the investigators to avoid retransplantation for these indications in the latter portion of the study period and, potentially, to confounding by time.

Figure 3.

Survival of lung retransplant recipients (by indication) and initial lung transplant recipients before January 2004 (p = 0.001 for primary graft dysfunction (PGD) and airway complications vs. bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) and initial transplant) (Adapted from Strueber M, Fischer S, Gottlieb J, et al. Long-term outcome after pulmonary retransplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132(2):407–412, with permission.)

Aigner et al. published data from 46 patients who underwent lung retransplantation between 1995 and 2006 in Vienna [20]. They found that patients retransplanted for BOS (N = 19) had one- and five-year survival of 72.5% and 61.3% respectively which was significantly better than the survival of patients retransplanted for PGD (N = 23) (Figure 4) (although these estimates did not account for three patients who required re-retransplantation). There appeared to be improvement in outcomes over time with retransplant recipients from 2002 to 2006 having better survival than recipients from 1995 to 2001.

Figure 4.

Survival after lung retransplantation between 1995 and 2006 (p = 0.02 for primary graft dysfunction (PGD) vs. bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS), other differences were not significant) (Adapted from Aigner C, Jaksch P, Taghavi S, et al. Pulmonary retransplantation: is it worth the effort? A long-term analysis of 46 cases. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27(1):60–65, with permission.)

The largest retrospective cohort study of lung retransplantation compared modern lung retransplantation to both modern initial lung transplantation and to historical retransplantation in 79 centers in the US [6]. Patients in the “modern retransplant cohort” received a first lung retransplantation between January 2001 and May 2006 (N = 205) (Table 2). Patients who underwent initial lung transplant during this time period were included in the “modern initial transplant cohort” (N = 5,657). Patients who underwent a first lung retransplant between January 1990 and December 2000 comprised the “historical retransplant cohort” (N = 184). The modern retransplant cohort was significantly older than the historical retransplant cohort but younger than the modern initial transplant cohort (Table 2). Most of the patients in the three cohorts had either chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or diffuse parenchymal lung disease as the indication for initial lung transplantation. These diagnoses were less frequent in the modern retransplant patients than in the initial transplant patients, and pulmonary arterial hypertension and cystic fibrosis/bronchiectasis were more frequent. Hypertension, renal failure, and corticosteroid use were significantly more common in the modern retransplant cohort than in the modern initial transplant cohort, and diabetes mellitus was more common in the modern retransplant cohort than both of the other cohorts.

Table 2.

Recipient and procedure characteristics of modern retransplant recipients (2001–2006), historical retransplant recipients (1990–2000), and modern initial transplant recipients (2001–2006) in the US

| Characteristic | Modern Retransplant (N = 205) | Historical Retransplant (N = 184) | Modern Initial Transplant (N = 5657) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 43 ± 16 | 39 ± 17† | 50 ± 14* | ||

| Gender, Female | 109 (53%) | 103 (56%) | 2721 (48%) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 182 (89%) | 169 (92%) | 4935 (87%) | ||

| Black | 13 (6%) | 12 (6%) | 414 (7%) | ||

| Other | 10 (5%) | 3 (2%) | 308 (5%) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22 ± 5 (N = 202) |

22 ± 6 (N = 172) |

24 ± 5* (N = 5456) |

||

| Initial diagnosis | |||||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 66 (32%) | 70 (38%) |

|

2505 (44%) |

|

| Diffuse parenchymal lung disease | 52 (25%) | 32 (17%) | 1690 (30%) | ||

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 24 (12%) | 28 (15%) | 240 (4%) | ||

| Cystic fibrosis/Bronchiectasis | 53 (26%) | 33 (18%) | 977 (17%) | ||

| Other | 10 (5%) | 21 (11%) | 245 (4%) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 74 (36%) | 22 (17%)* (N = 128) |

608 (11%)* (N = 5595) |

||

| Hypertension | 80 (40%) (N = 199) |

45 (36%) (N = 125) |

993 (18%)* (N = 5540) |

||

| Renal failure | 72 (36%) (N = 200) |

56 (30%) (N = 133) |

486 (9%)* (N = 5583) |

||

| Corticosteroid use | 151 (79%) (N = 191) |

106 (82%) (N = 129) |

1881 (35%)* (N = 5425) |

||

| Mechanical ventilation at time of transplant procedure | 40 (20%) | 45 (25%) | 145 (3%)* | ||

| Indication for retransplantation | |||||

| Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome | 107 (52%) | 103 (56%) | -- | ||

| Primary graft dysfunction | 32 (16%) | 16 (9%) | -- | ||

| Acute rejection | 7 (3%) | 4 (2%) | -- | ||

| Other or unknown | 59 (27%) | 61 (33%) | -- | ||

| Median time from initial transplant, years | 3.1 (1, 6.5) | 1.9 (0.5–3.1)* | --- | ||

| Early retransplant (< 30 days from initial transplant) | 22 (11%) | 31 (17%) | -- | ||

| Procedure type (Initial:Retransplant) | (N = 201) | (N = 173) | |||

| Bilateral:Bilateral (En bloc included) | 67 (33%) | 56 (32%) |

|

-- | |

| Bilateral:Single | 41 (20%) | 13 (8%) | -- | ||

| Single:Bilateral | 31 (15%) | 30 (17%) | -- | ||

| Single:Single (Ipsilateral) | 9 (4%) | 33 (19%) | -- | ||

| Single:Single (Contralateral) | 53 (26%) | 41 (24%) | -- | ||

| Ischemic time, hours | 5.2 ± 1.9 (N = 182) |

5.0 ± 1.8 (N = 157) |

4.8 ± 1.7† (N = 4934) |

||

Data are mean ± SD or N (%).

p < 0.001 vs. modern retransplant.

p < 0.01 vs. modern retransplant.

Data from Kawut SM, Lederer DJ, Keshavjee S, et al. Outcomes after lung retransplantation in the modern era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):114–120.

Modern and historical retransplant patients were more likely to require mechanical ventilation at the time of transplant than were initial transplant recipients, and more than half of the modern and historical retransplant procedures were performed for BOS. Half of the modern retransplant patients received initial bilateral lung or heart-lung transplantation, and most of these patients went on to receive bilateral lung retransplantation. Modern retransplant patients more often underwent single lung retransplantation after initial bilateral lung transplant than did historical retransplant patients and less frequently underwent ipsilateral single lung retransplantation.

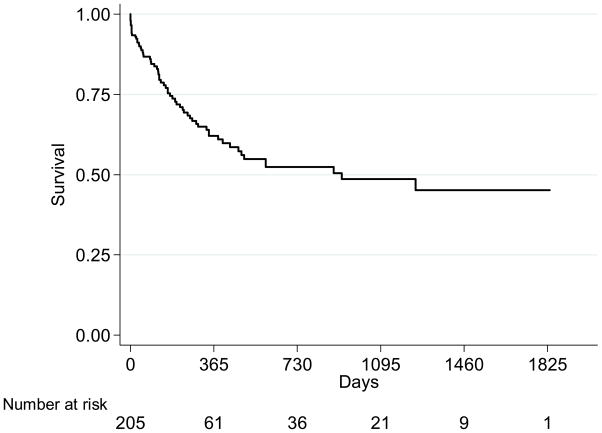

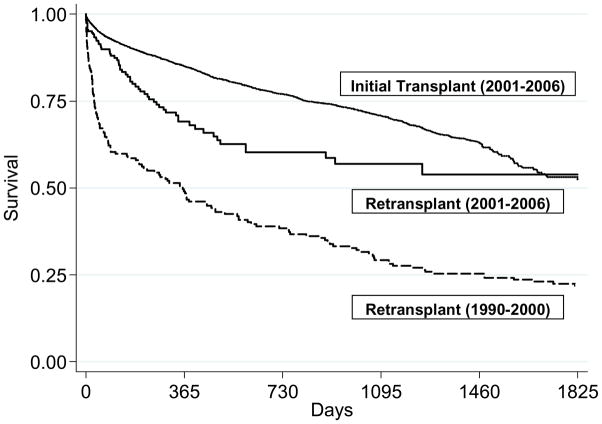

Survival estimates at one and five years after modern lung retransplantation were 62% and 45% respectively (Figure 5). Patients undergoing modern lung retransplantation had a significantly lower risk of death after the procedure than that of the historical retransplant cohort, independent of recipient and donor variables, pulmonary diagnosis, and mechanical ventilation at the time of transplant (Table 3)(Figure 6). On the other hand, patients undergoing modern lung retransplantation still had a 30% higher risk than that of patients undergoing modern initial transplantation (Bivariate model, Table 3). Adjustment for recipient and surgical factors attenuated the effect estimates, indicating that differences in these factors explained some (but not all) of the increased risk associated with retransplantation (Multivariate models 1 and 2, Table 3). Further adjustment for the presence of renal failure reduced the hazard ratio even further, showing that kidney disease accounted for much of the increased risk of death seen in the retransplantation recipients when compared to initial transplant patients (Multivariate model 3, Table 3). Retransplant patients had twice the risk of BOS as initial transplant patients (95% CI 1.4–3.0, p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimate of lung retransplant recipients in the US from 2001 to 2006 (Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © American Thoracic Society. From Kawut SM, Lederer DJ, Keshavjee S, et al. Outcomes after lung retransplantation in the modern era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):114–120, Official Journal of the American Thoracic Society, Diane Gern, Publisher.)

Table 3.

Proportional hazards models comparing the risks of death in modern retransplant recipients (2001–2006), historical retransplant recipients (1990–2000), and modern initial transplant recipients (2001–2006) in the US

| HR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modern lung retransplantation vs. Historical lung retransplantation | |||

| Bivariate | 0.7 | 0.5–0.9 | 0.006 |

| Multivariate* | 0.7 | 0.5–0.97 | 0.03 |

| Modern lung retransplantation vs. Modern initial lung transplantation | |||

| Bivariate | 1.3 | 1.2–1.5 | 0.001 |

| Multivariate Model 1† | 1.2 | 1.1–1.4 | 0.003 |

| Multivariate Model 2‡ | 1.2 | 1.04–1.3 | 0.03 |

| Multivariate Model 3§ | 1.1 | 1.0–1.3 | 0.11 |

Adjusted for recipient age, gender, race/ethnicity, initial diagnosis, single/bilateral retransplantation, indication for retransplantation, ischemic time, mechanical ventilation, donor age, race, and mode of death, early retransplantation, diabetes mellitus, and renal failure.

Adjusted for recipient age, gender, race/ethnicity, body mass index, initial diagnosis, single/bilateral transplantation, ischemic time, and mechanical ventilation.

Model 1 + adjustment for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, corticosteroid use.

Model 2 + adjustment for renal failure.

Data from Kawut SM, Lederer DJ, Keshavjee S, et al. Outcomes after lung retransplantation in the modern era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):114–120.

Figure 6.

Survival estimates of modern initial lung transplantation (2001–2006), modern lung retransplantation (2001–2006), and historical lung retransplantation recipients (1990–2000) after adjustment for age (55 yr), sex (female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white), procedure type (bilateral), mechanical ventilation (none), and pulmonary diagnosis (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) (p < 0.05 for all comparisons) (Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © American Thoracic Society. From Kawut SM, Lederer DJ, Keshavjee S, et al. Outcomes after lung retransplantation in the modern era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):114–120, Official Journal of the American Thoracic Society, Diane Gern, Publisher.)

While mechanical ventilation at the time of retransplantation and early retransplantation (< 30 days from the initial transplant) were both significantly associated with an increased risk of death in unadjusted analyses in the modern retransplant cohort (Table 4), only early retransplantation and male donor gender were independently associated with an increased risk of death. The one-year survival for the 22 patients who underwent early retransplantation was only 31%, whereas it was 66% for others.

Table 4.

Association of recipient and donor characteristics with the risk of death in modern lung retransplant recipients (2001–2006) in the US

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Bivariate Models |

|||

| Recipient | |||

| Age (per 10 year increment) | 0.9 | 0.8–1.1 | 0.45 |

| Male gender | 1.4 | 0.8–2.2 | 0.23 |

| Race/Ethnicity: Others vs. Non-Hispanic white | 1.6 | 0.8–3.2 | 0.21 |

| Body mass index (per 5 unit increment) | 1.0 | 0.9–1.0 | 0.92 |

| Initial diagnosis (vs. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) | |||

| Diffuse parenchymal lung disease | 1.5 | 0.7–2.8 | 0.27 |

| Cystic fibrosis/Bronchiectasis | 1.3 | 0.7–2.5 | 0.43 |

| Pulmonary arterial hypertension | 1.2 | 0.6–2.5 | 0.67 |

| Renal failure | 1.3 | 0.8–2.2 | 0.30 |

| Mechanical ventilation at the time of retransplantation | 2.0 | 1.1–3.4 | 0.02 |

| Indication for retransplantation (vs. BOS) | |||

| Primary graft dysfunction | 1.1 | 0.6–2.1 | 0.72 |

| Acute rejection | 1.2 | 0.4–3.8 | 0.81 |

| Other or unknown | 0.9 | 0.5–1.7 | 0.80 |

| Donor | |||

| Age (per 10 year increment) | 1.1 | 0.9–1.3 | 0.26 |

| Male gender | 1.7 | 1.0–3.0 | 0.04 |

| Procedure | |||

| Early retransplant (< 30 days from initial transplant) | 2.6 | 1.4–4.9 | 0.003 |

| Procedure type (Initial:Retransplant) (vs. Bilateral:Bilateral) | |||

| Bilateral:Single | 0.9 | 0.4–1.7 | 0.71 |

| Single:Bilateral | 1.1 | 0.6–2.2 | 0.74 |

| Single:Single (Ipsilateral) | 2.3 | 0.9–6.1 | 0.09 |

| Single:Single (Contralateral) | 0.5 | 0.2–1.0 | 0.05 |

| Ischemic time (per 1 hour increment) | 1.1 | 0.9–1.2 | 0.44 |

|

Multivariate Model |

|||

| Early retransplant (< 30 days from initial transplant) | 2.8 | 1.5–5.4 | 0.001 |

| Donor male gender | 1.9 | 1.1–3.2 | 0.02 |

Data from Kawut SM, Lederer DJ, Keshavjee S, et al. Outcomes after lung retransplantation in the modern era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):114–120.

This study showed that outcomes after lung retransplantation in the US have improved over time; however, survival after lung retransplantation was still not as good as that after initial lung transplantation. Based on the multivariate analyses, these differences seemed attributable to a higher prevalence of renal failure and other recipient characteristics. The presence of renal failure in retransplant recipients is likely attributable to long-standing use of calcineurin inhibitors and has been associated with poor outcomes in non-renal solid organ transplant recipients [21]. Renal failure is associated with a variety of medical comorbidities that could shorten survival. Alternatively, the presence of renal failure may just serve as a surrogate marker for either the duration and intensity of calcineurin inhibitor-based immunosuppression or the degree of disease of the microcirculation in other organs leading to higher risk after retransplantation.

Early retransplantation independently conferred a high risk for a poor outcome in the modern retransplant cohort. Mechanical ventilation was also associated with an increased risk of death. After adjusting for timing of retransplantation however, mechanical ventilation was no longer associated with mortality. Therefore, mechanical ventilation may not be a risk factor for patients who are farther out from the initial transplant (e.g., with BOS).

In summary, the one- and five-year survival estimates for retransplantation in the modern era are approximately 60–80% and 45–65% respectively. Retransplantation for BOS leads to survival estimates in the upper portions of these ranges. Early retransplantation (for PGD, for example) results in very poor outcomes, whereas selected patients receiving mechanical ventilation farther out from initial transplant may do well. There is a an increased risk of BOS after retransplantation, which may explain the worse outcomes compared to initial transplant, but recipient characteristics and specifically renal failure may contribute to poor outcomes as well.

Is Retransplantation Ethically Justified?

Whereas the indications, selection criteria, and outcomes for retransplantation are reasonably straightforward, the ethical justification for retransplantation is less so in the setting of scarce organs. Since organ donation comes from the deceased and their families and “donated organs belong to the community” [22, 23], the populace views regarding retransplantation are therefore important to consider. A recent systematic review summarized 15 studies eliciting community preferences for organ allocation [24]. Sixty percent or more of respondents preferred allocating organs to initial transplant candidates rather than to retransplant candidates. However, some believed that those who had already received a transplant that failed for medical reasons might have proved themselves able to care for the transplant, warranting priority for another allograft. The vast majority of respondents preferred allocating organs to those with the best chance at survival and improved quality-of-life with transplant, making these guiding principles for retransplantation.

Several authors have directly addressed the ethics of solid organ retransplantation [25–28]. The principle of justice mandates there be equity in distribution of benefits and harms among transplant candidates, however a rational planner could either discount or favor retransplantation under this principle. For example, it would be rational for an individual (unaware of the future) to prefer a system where the maximal number of people get the opportunity for initial transplantation, rather than one where some undergo retransplantation before others get an initial transplant. In a different scenario, allocating a second organ to a particular patient who has already proven him- or herself capable of adhering to the complicated medical regimen might increase the chance of success of that transplant and provide greater overall benefit to the population of transplant candidates, still fulfilling the principle of justice in a different way.

Under a just system, transplant candidates each deserve an equal portion of the finite/limited healthcare “pie”, all else being equal [27]. One individual should not get a second allograft (or piece) before others have had their first. The problem is that candidates are not perfectly equal. If the “pie” is considered as the larger construct of health and society, some retransplant candidates may not have had all of the advantages (whether medical, financial, or social) of candidates for initial transplantation. In this scenario, a chance at retransplantation might be due to the transplant recipient, all things considered. The principles of justice would seem to favor lung retransplantation in certain instances, but by themselves are not sufficient to justify retransplant.

Maximizing efficacy (or utilitarianism) refers to the goal of increasing total benefits to transplant candidates overall by targeted organ allocation to those most likely to benefit. Utilitarianism would mandate that initial transplantation be prioritized over retransplantation, since retransplant recipients generally demonstrate a worse survival [29]. Even with initial transplantation, patients with some diagnoses (e.g., pulmonary hypertension or sarcoid) have poorer outcomes than patients with other diagnoses (e.g., cystic fibrosis and COPD). Full pursuit of a utilitarian approach could dictate that all lung allografts be used for those with the best post-transplant survival (or the maximal net benefit), potentially eliminating patients with certain lung disease diagnoses (or requiring retransplant) from candidacy. This of course would appear inequitable and unpalatable for initial transplant, and the lung transplant community has already factored efficacy differences into the allocation system to balance utilitarianism with justice and urgency (e.g., the appeal process for severely ill patients with pulmonary hypertension), suggesting that neither the community nor policymakers are fully at ease with a utilitarian priority system that sacrifices egalitarianism [27]. As retransplantation has similar or better outcomes than initial transplant in certain cases, a utilitarian approach seemingly justifies the allocation of allografts for lung retransplantation in such instances.

Prioritarianism favors the worst off [29, 30] and directs the allocation of organs to the sickest first, no matter what the outcomes. This approach is not justifiable for either initial transplant or retransplantation in the setting of scarce allograft resources, as efficacy would be significantly compromised and it only considers the “sickest” at the current time and neglects others who may progress. Similarly, transplant physicians and surgeons may understandably feel bound to prioritize for retransplantation a patient whom they have transplanted and cared for (often for years), appropriately regarding as “paramount” the interest of their own patient [31, 32]. However, it is not only acceptable to prioritize the needs of other patients over ones own patient when considering retransplantation (just as with initial transplantation or other scenarios requiring triage or rescue), but the exceptions are also frequent enough that some have suggested professional guidelines for such situations [31].

A “youngest-first” strategy (where organs for retransplantation of a significantly younger individual could be prioritized over the initial transplant of an older individual) might be justifiable, beyond the impact of age on urgency or benefit. Public preference strongly supports the allocation of scarce life-saving interventions to younger individuals [24, 29, 33]. “Because [all people] age, treating people of different ages differently does not mean that we are treating persons unequally.”[29, 34] While possibly viewed as “ageism”, all 66 year olds were once 25 and had they needed a lung retransplantation would have had the advantage extended to them under such a system, therefore providing “equal opportunity”.

In the US, urgency and efficacy (in terms of net survival benefit at one year) determine priority of lung offers within the constraints of geography, compatible blood type, and body size. The policy of UNOS is to enhance the overall availability of allografts, balance medical utility (net benefit to all transplant patients as a group) and justice (equity in distribution of benefits and burdens among transplant patients), provide organ offers within comparable time periods for patients depending on their circumstances, and respect the autonomy of persons [22]. Accordingly, retransplantation would (and should) be prioritized lower than many (but not all) initial transplants, but appears ethically justifiable by the same principles that guide all organ allocation.

A key element to the fair allocation of organs for retransplantation lies in the accuracy of the metric of “net benefit” used to distribute organs. The LAS system is based on survival at one year; whether this is the best measure of benefit is controversial. Also, the LAS system did not derive a prediction model specifically for retransplant candidates (due to the small population). Therefore, the LAS scores assigned to retransplant candidates are derived from models based on patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [5]. If the efficacy of lung retransplantation is overestimated by the model, the recent increase in retransplantation procedures under the LAS could be unjustified and jeopardize the ethical stance of lung allocation for retransplantation. For example, 10% of recent LAS scores for retransplant candidates overestimated post-transplant survival by ≥ 231 days and 10% underestimated survival ≥ 83 days, demonstrating somewhat greater variability than for transplant candidates overall [7]. In order to maintain the appropriate and ethical prioritization of organs for retransplantation in the US, there should be focused efforts on refining the net benefit calculus for this group, lest misclassification or a spuriously high or low calculated priority threaten just allocation of lung allografts.

In summary, there is a growing number of lung allografts used for retransplantation and a greater percentage of lung transplants that are retransplantations, even though the absolute numbers remain small. The criteria for retransplantation are similar to those for initial transplant, but the optimal technical approach is not clear. Survival after lung retransplantation has improved over time, although it is still worse than after initial transplant. Retransplantation early after initial transplant continues to pose a prohibitive risk and should be avoided. Retransplant is ethically justified, however prioritization of lung allografts for both initial transplant and retransplantation needs to be guided by the principles of justice and efficacy and must be based on accurate estimates of net benefit. Future efforts should focus on understanding the mechanisms of the increased risk of BOS and higher mortality after retransplantation, honing the selection of optimal candidates and technical approach, and refining the ethical allocation of organs for this procedure.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Scott D. Halpern, MD, PhD, MBE for his insightful comments after review of this manuscript. This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-37011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vakil N, Mason DP, Yun JJ, et al. Third-time lung transplantation in a patient with cystic fibrosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christie JD, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: twenty-seventh official adult lung and heart-lung transplant report--2010. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(10):1104–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Data from OPTN. 2010 Dec 3; http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov.

- 4.Eberlein M, Garrity ER, Orens JB. Lung allocation in the United States. Clinics in Chest Medicine. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.02.004. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan TM, Murray S, Bustami RT, et al. Development of the new lung allocation system in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(5 Pt 2):1212–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawut SM, Lederer DJ, Keshavjee S, et al. Outcomes after lung retransplantation in the modern era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(1):114–120. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1132OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.2009 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant Data 1999–2008. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation; Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orens JB, Estenne M, Arcasoy S, et al. International guidelines for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2006 update--a consensus report from the Pulmonary Scientific Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25(7):745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keshavjee S. Retransplantation of the lung comes of age. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132(2):226–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novick RJ, Andreassian B, Schafers HJ, et al. Pulmonary retransplantation for obliterative bronchiolitis. Intermediate-term results of a North American-European series. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107(3):755–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novick RJ, Kaye MP, Patterson GA, et al. Redo lung transplantation: a North American-European experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993;12(1 Pt 1):5–15. discussion 15–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novick RJ, Schafers HJ, Stitt L, et al. Recurrence of obliterative bronchiolitis and determinants of outcome in 139 pulmonary retransplant recipients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110(5):1402–1413. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70063-3. discussion 1413–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novick RJ, Schafers HJ, Stitt L, et al. Seventy-two pulmonary retransplantations for obliterative bronchiolitis: predictors of survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60(1):111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novick RJ, Stitt L, Schafers HJ, et al. Pulmonary retransplantation: does the indication for operation influence postoperative lung function? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112(6):1504–1513. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70009-0. discussion 1513–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novick RJ, Stitt LW, Al-Kattan K, et al. Pulmonary retransplantation: predictors of graft function and survival in 230 patients. Pulmonary Retransplant Registry. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65(1):227–234. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(97)01191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brugiere O, Thabut G, Castier Y, et al. Lung retransplantation for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: long-term follow-up in a series of 15 recipients. Chest. 2003;123(6):1832–1837. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.6.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schafers HJ, Hausen B, Wahlers T, et al. Retransplantation of the lung. A single center experience. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1995;9(6):291–295. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(05)80184-8. discussion 296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osaki S, Maloney JD, Meyer KC, et al. Redo lung transplantation for acute and chronic lung allograft failure: long-term follow-up in a single center. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34(6):1191–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strueber M, Fischer S, Gottlieb J, et al. Long-term outcome after pulmonary retransplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132(2):407–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aigner C, Jaksch P, Taghavi S, et al. Pulmonary retransplantation: is it worth the effort? A long-term analysis of 46 cases. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27(1):60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojo AO, Held PJ, Port FK, et al. Chronic renal failure after transplantation of a nonrenal organ. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(10):931–940. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egan TM. Ethical issues in thoracic organ distribution for transplant. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(4):366–372. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Childress JF. The gift of life: ethical issues in organ transplantation. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1996;81(3):8–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong A, Howard K, Jan S, et al. Community preferences for the allocation of solid organs for transplantation: a systematic review. Transplantation. 2010;89(7):796–805. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181cf1ee1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mentzer SJ, Reilly JJ, Jr, Caplan AL, et al. Ethical considerations in lung retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1994;13(1 Pt 1):56–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novick RJ. Heart and lung retransplantation: should it be done? J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17(6):635–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ubel PA, Arnold RM, Caplan AL. Rationing failure. The ethical lessons of the retransplantation of scarce vital organs. Jama. 1993;270(20):2469–2474. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.20.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotloff RM. Lung retransplantation: all for one or one for all? Chest. 2003;123(6):1781–1782. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.6.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Persad G, Wertheimer A, Emanuel EJ. Principles for allocation of scarce medical interventions. Lancet. 2009;373(9661):423–431. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parfit D. Equality and priority. Ratio. 1997;10:202–221. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wendler D. Are physicians obligated always to act in the patient’s best interests? J Med Ethics. 2010;36(2):66–70. doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.033001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.AMA. [Accessed Dec 1, 2010.];Principles of medical ethics. Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/code-medical-ethics/principles-medical-ethics.shtml.

- 33.Tsuchiya A, Dolan P, Shaw R. Measuring people’s preferences regarding ageism in health: some methodological issues and some fresh evidence. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(4):687–696. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00418-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daniels N. Am I my parents’ keeper? An essay on justice between the young and the old. 1988 [Google Scholar]