Abstract

Background

The efficacy of smoking cessation interventions for hospital patients has been well described, but we know little regarding implementation and outcomes of real-world programs.

Objective

To describe the services provided and outcomes of an academic medical center-based tobacco treatment service (UKanQuit) located in the Midwestern United States.

Method

This is a descriptive observational study. Both quantitative and qualitative data of all patients treated by UKanQuit over a one-year period were analyzed.

Results

Among 513 patients served, average interest in quitting was 7.9, SD 2.9 on a scale of 0 to 10. Over 1 in 4 had been given an in-hospital medication to ameliorate withdrawal prior to seeing a counselor. Counselors recommended medication changes for 1 in 3 patients, helped 73% set a goal for quitting or reducing tobacco use, and fax referred 56% to quit lines. Six-month follow-up (response rate, 46%) found a 7-day abstinence rate of 32% among respondents for an intent-to-treat abstinence rate of 15%. Post-discharge, 74% made at least one serious quit attempt, 34% had used a quit smoking medication, but only 5% of those referred to the quitline reported using it.

Conclusions

In a hospital setting, interest in quitting is high among smokers who requested to see a tobacco counselor but administration of in-patient medications remains low. Many smokers are making unassisted quit attempts post-discharge because utilization of cessation medications and quitline counseling were low. Fax-referral to quitline may not, on its own, fulfill guideline recommendations for post-discharge follow-up.

INTRODUCTION

Hospitalization can be considered a ‘teachable moment’ for smoking cessation 1–3 for the 6.5 million adult smokers who are hospitalized in the United States each year.4 Smokers who receive tobacco treatment during hospitalization and outpatient follow up treatment for at least one month are more likely to quit than patients who receive no treatment.5, 6

Unless tobacco treatment is explicitly delegated to other providers, physicians shoulder the responsibility of encouraging smokers to quit and prescribing smoking cessation medications. This is problematic in that physicians sometimes fail to counsel their patients about quitting smoking 7,8 or recommend outpatient follow up.9 Few hospitals provide comprehensive treatment. In a review of 33 studies on the prevalence of smoking care delivery in hospitals, 3 hospitals reported they provided advice to quit alone, 29 provided advice plus counseling and assistance in quitting, and 8 provided advice or prescription for cessation pharmacotherapy.9 Although post-discharge support is a key component of effective treatment for hospitalized smokers,6 only 11 reported providing follow-up treatment, or referral for follow-up treatment, after discharge. Among these 11 hospitals, respondents reported they provided referral or follow-up to 1%–74% of their smokers, with a median percentage of 24%. The one study that specified the type of outpatient treatment provided reported the hospital provided the state quitline number to smokers.

Instituting a dedicated smoking cessation program may enhance inpatient treatment, outpatient follow up, and treatment outcomes. Two studies have found that institutional smoking cessation programs increased the likelihood that patients would receive treatment and quit compared to hospitals without dedicated programs. 10, 11

Although many U.S. hospitals are developing programs to provide systematic treatment for tobacco dependence,9 little is known regarding how programs structure their staff, enroll patients, or provide treatment to patients that smoke. Instituting tobacco treatment services usually requires policy change and system-wide approaches with quality improvement endpoint goals. 8, 12–14 In the United States, elements of these services include 1) developing a cadre of trained tobacco treatment specialists, 2) implementing hospital systems for identifying smokers and referring them to the service, 3) providing inpatient treatment based on current treatment guidelines 15 and 4) providing or facilitating follow up treatment after discharge, often via fax-referral to tobacco quit lines. This systematic approach is still lacking in many hospitals.

To date, few evaluations of dedicated hospital-based smoking cessation programs have been reported in the literature. 8, 11 The purpose of this study is to describe patient characteristics and outcomes of a dedicated tobacco treatment service, with paid staff, in a large academic medical center. We describe treatment protocols, profile patients served, describe treatments provided, and summarize 6-month post-discharge outcomes for smokers referred to the UKanQuit service over a one-year period. We close with lessons learned on how to improve the delivery of tobacco treatment to hospitalized patients.

METHODS

Design and setting

This is a descriptive observational study of a tobacco treatment program in a large Midwestern academic medical center between September 1, 2007 and August 31, 2008. The specialty tobacco treatment service (UKanQuit) was established when the hospital campus went smoke free on September 1, 2006. Patients are referred to the service via the hospital electronic medical record. As nurses complete electronic forms on patients admitted to their units, the electronic medical record (EMR) prompts nurses to ask patients if they smoke, ask smokers if they would like tobacco treatment medication to prevent withdrawal symptoms while in the hospital, and ask smokers if they would like to talk to a tobacco treatment specialist during their hospital stay. Those who respond ‘yes’ to the final question are placed on an electronic list for UKanQuit services. Physicians and other health care providers can also order consultation from the UKanQuit service. A description of smokers admitted to the hospital and predictors of referral to UKanQuit within the first year of service is presented elsewhere.16,17

The UKanQuit staff consists of an interdisciplinary team of counselors with Ph.D., Masters degrees, and/or substantial experience in case management and substance abuse treatment. All have received intensive training and supervision in treating tobacco dependence. All participate in UKanQuit counseling on a part-time basis, and spend the remainder of their effort as research assistants and counselors on smoking cessation research projects in the medical center. Hence, staffing consists of 1 full-time equivalent counselor, 0.15 full-time equivalent director (Richter), and 0.05 full-time equivalent medical director (Ellerbeck). The program is funded through a contract with the hospital. We are in the process of hiring a nurse practitioner to create a more sustainable funding stream for the program because nurse practitioners can bill cessation services.

UKanQuit provides hospital counseling from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. on weekdays. UKanQuit staff meets weekly for counseling supervision, strategic planning, continuing education, and troubleshooting difficult cases. In addition to treating smokers, the UKanQuit staff provides training and consultation to hospital personnel via grand rounds and other presentations. The service also provides a platform for medical students and residents to conduct focused research related to quality improvement. To facilitate systematic treatment of tobacco, UKanQuit developed the hospital treatment protocol for nursing staff, developed evidence-based written self-help materials that are accessible to hospital staff via the hospital printing system, and developed and instituted a tobacco treatment order set that was recently integrated into the EMR and automatically becomes prioritized as a recommended order set for all patients who report they have smoked in the past 30 days.

Procedures

UKanQuit staff retrieves patient details from the EMR and visits patients at their bedside. All hospital services refer to UKanQuit. UKanQuit provides counseling to Spanish speakers through bilingual/bicultural staff and hospital translators assist UKanQuit staff in counseling patients who speak other languages. The staff conducts a brief assessment at the bedside to inform treatment and contact patients 6 months following inpatient treatment to assess outcomes and provide additional support and referral. This study evaluating the UKanQuit program was approved by the medical center’s Institutional Review Board.

Program intervention

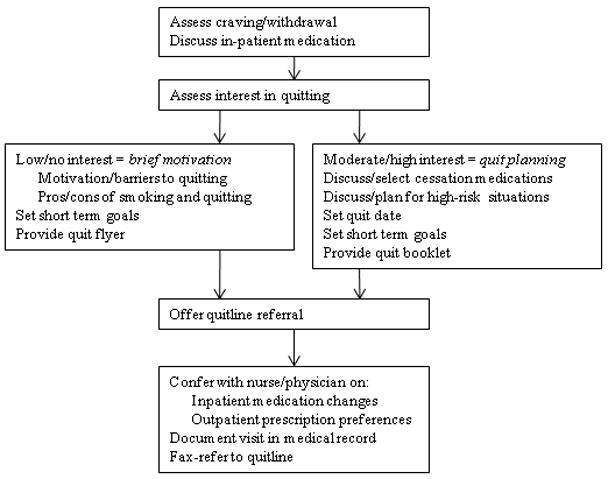

UKanQuit staff visit patients at the bedside to deliver tobacco treatment. This consists of a) assessing withdrawal; b) working with the health care team to adjust nicotine replacement to keep the patient comfortable; c) assessing patients’ interest in quitting smoking; d) providing brief motivational intervention to patients not interested in quitting; and e) providing assistance in quitting (developing a quit plan, arranging for medications on discharge) to patients interested in quitting. UKanQuit staff recommend medications based on the patients’ level of dependence, history of cessation and cessation medication preferences. The recommendation is communicated in person and by chart documentation to the medical team, usually by the nursing staff. The patients’ resident or attending physician makes the final determination regarding medication provided. The hospital has NRT (patch, gum, and lozenge), bupropion, and varenicline in its formulary. Patients are then offered an option of fax referral to the state tobacco quitline for follow-up counseling. UKanQuit staff documents the services provided in the EMR via SOAR (Subjective, Objective, Assessment and Referral) notes.

Measures

Baseline measures

These were collected from the UKanQuit one-page program intake form, which UKanQuit designed to collect the minimal information necessary to conduct medication and behavioral counseling, to maximize counseling time, and to fit into the dense schedule of each patient’s hospital stay. Demographic measures include age, gender and ethnicity. Smoking behavior measures include number of years smoked, number of cigarettes per day, a single item from the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence that assesses time to first cigarette after waking, 18, 19 interest in quitting smoking (on a 0–10 scale, with 10 being very interested in quitting), and a single item from the self report version of the Minnesota Withdrawal Nicotine Withdrawal Scale (MNWS) that asks smokers to rate their desire or craving to smoke over a specified period. The single item craving measure from the MNWS has been found to have high reliability and good construct validity and is neither less sensitive to abstinence nor less reliable than the ten-item questionnaire of smoking urges QSU-brief used in laboratory and clinical trials.20 We asked about craving over the past 24 hours on a scale from 0 (none) to 4 (severe).21

Process Measures

Counselors also document the treatment they provided to smokers including the time spent with patients during counseling, provision of written self-help materials, whether smokers set goals for quitting, whether hospital staff had already placed the smoker on a tobacco treatment medication, whether smokers are interested in increasing or changing their medication, whether the smoker wants smoking cessation medication on discharge, whether UKanQuit staff submitted a recommendation to hospital staff to make a medication change and/or provide a prescription for medication on discharge, plans for post-discharge follow up (fax-referral of patients to the state tobacco quitline or acceptance of UKanQuit counseling after discharge), and whether the patient agrees to be contacted at 6 months post-discharge for follow up assessment and assistance.

Follow up measures

Outcome measures were collected by telephone 6 months post-discharge by study staff who were not involved in the in-hospital counseling. Call attempts to reach each patient ranged from 1 to 11. Measures included self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence rates, the number of quit attempts lasting over 24 hours, and cigarettes smoked per day among continuing smokers. Patients are asked if they participated in counseling through the tobacco quitline. Scaled (0–10) items assess how important it is to the patients to quit smoking or remain quit, how confident they are in being able to quit or remain quit, and how satisfied they were with the assistance provided by UKanQuit. A yes/no item assesses whether patients think the program should be continued. In addition, UKanQuit asked two open-ended questions to qualitatively assess satisfaction with the program and elicit suggestions for improvements. The questions were: ‘What, if anything, was helpful to you about our services?’ and ‘How can UKanQuit better help people stop smoking?’

Analyses

Categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and percentages; continuous variables were summarized by means and standard deviations. We compared baseline characteristic differences between respondents and non-respondents at 6 months follow-up using Chi-square for categorical variables and T-Test for continuous variables. We also compared cigarettes per day at baseline and 6 months post-discharge in smokers who were not able to quit using paired T-Test. All analyses were done with SPSS 17.0 statistical package. Open-ended questions were analyzed using the framework synthesis method.22 Following examination and familiarization with the data, we developed an initial list of themes. We then categorized the responses by these themes using numerical codes. Each thematic code was summarized as a percentage of all responses. Those responses that fit into multiple thematic codes were multiply coded.

RESULTS

Baseline

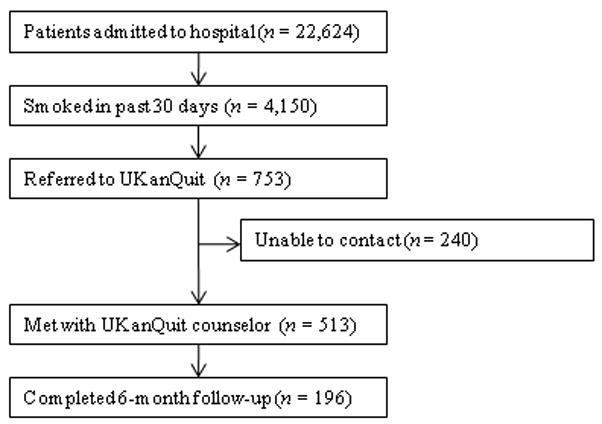

Within the study period (September 1, 2007 to August 31, 2008), 22,624 patients were admitted to the medical center. Four thousand one hundred and fifty were current smokers (i.e. smoked within the past 30 days). UKanQuit Staff met with 513 (68%) of 753 patients referred to the service. Some of the reasons why 32% of referred patients were not seen by the UKanQuit Staff have been described in our previous paper.17 These include “patient was asleep,” “doctor in the room,” “out of bed for procedure,” and “unable to speak.” Table 1 displays the characteristics of 513 smokers treated by UKanQuit from September 1, 2007 to August 31, 2008. Patients were predominantly White (74%) with mean age 50 years. Slightly more than half of smokers were male (57%). They had smoked an average of 18 cigarettes per day for a mean duration of 29 years, and over half (58%) smoked within 5 minutes of waking suggesting a high level of dependence. On a scale of 1–10 the mean interest in quitting was 7.9 (SD 2.9) and the mean craving score on a scale of 0–4 was 1.2 (SD 1.4) suggesting slight to mild craving.

Table 1.

Demographic, smoking characteristics and treatment provided to 513 patients seen by UKanQuit Service from Sept 1, 2007 to Aug 31, 2008a

| Characteristics | Treated (n = 513) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Mean age (SD), years | 50.2 (13.6) |

| Male, n (%) | 291 (56.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 371 (73.6) |

| AA | 107 (21.2) |

| Latino | 18 (3.6) |

| Other | 8 (1.6) |

| Referral source, n (%) | |

| Nursing Profile | 477 (94.1) |

| Physician | 5 (1.0) |

| Other | 25 (4.9) |

| Smoking characteristics | |

| Mean no of years smoked (SD) | 28.9 (14.6) |

| Smokes within 5 min of waking n (%) | 270 (58.3) |

| Mean cigarettes smoked per day (SD) | 18.4 (12.6) |

| Mean interest in quitting (SD)* | 7.9 (2.9) |

| Mean craving (SD)** | 1.2 (1.4) |

| Tobacco treatment provided | |

| Counseling | |

| Average time spent with patients (SD) | 19.9 (9.1) |

| Received information packet, n (%) | 490 (97.4) |

| Set goals for quitting, n (%) | 352 (73.3) |

| Had quit plan, n (%) | 151 (33.2) |

| Accepted fax referral to quit line, n (%) | 277 (55.8) |

| Opted for UKanQuit counseling, n (%) | 29 (5.9) |

| Medication | |

| On smoking cessation medication, n (%) | 133 (26.2) |

| Interested in receiving or changing smoking cessation medication, n (%) | 132 (26.7) |

| Added or changed smoking cessation medication, n (%) | 195 (40.5) |

| Discharge med, n (%) | 196 (40.2) |

For each variable, subsamples were slightly different from total sample due to missing data. Missing data were not included in the analysis.

Interest in quitting range from 0–10.

craving range from 0–4

In-hospital treatment

Hospital staff had placed one in four of the patients on smoking cessation medication prior to the UKanQuit staff visit. Nineteen percent were on NRT (16.2% transdermal patch, 2.5% on lozenge, 0.8% on nicotine gum); 5% on Bupropion, 16.5% on Varenicline, and 2.5% on Clonidine. 1.7 % used a combination of Patch and Bupropion while 2.5 % used a combination of patch and gum. Staff provided 97% of the patients with written materials. Most patients (73%) set a goal for quitting or cutting down, and one-third developed quit plans. Fifty-six percent accepted fax referral to their state quit line, and six percent opted for follow up counseling with a UKanQuit counselor. Average time spent by UKanQuit with the patient was 20 minutes. Most of the patients treated (n = 426, 86%) agreed that UKanQuit staff can contact them for follow-up assessment at 6 months.

Outcomes

Staff successfully contacted 196 (46%) of the 426 patients who agreed to 6-month follow up. Responders were older (mean age 53, SD 12.6 vs. mean age 48, SD 13.8; p <0.001; were more interested in quitting (mean interest in quitting 8.4, SD 2.5 vs. 7.6, SD 3.1 p=0.001) and had a lower craving score at baseline (mean craving score 0.99, SD 1.3 vs. 1.29, SD 1.5; p <0.001) compared to non-responders. There were no differences between responders and non-responders by gender, number of cigarettes smoked per day, years of smoking, referral source, inpatient smoking cessation medication used or time spent with UKanQuit hospital staff during the inpatient visit.

Table 2 displays smoking behavior and smoking cessation-related characteristics of the respondents 6-month post-discharge. Over 70% attempted a quit attempt lasting at least 24 hours. The self reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence rate was 31.8% among respondents. The intent-to-treat quit rate was 14.6% among all participants who agreed to follow up, counting those who we could not contact as smokers. While 34% used pharmacotherapy, only 5% of those who were fax-referred to the quit line utilized the service. Most of the patients seen by the UKanQuit counselor considered quitting and staying quit important, mean 8.7, SD 2.3 and their confidence to quit or stay quit was above average, mean 6.6, SD 3.6. They rated the UKanQuit program very high, at 8.3, SD 2.8 on a scale of 0–10, and 98% of them wanted the program to continue. Of those who were not able to quit at 6 months, the mean number of cigarettes smoked per day decreased significantly from 17.8, SD 12.0 at baseline to 14.0, SD 9.7 at 6 months follow up (p<0.001).

Table 2.

Follow up data received from 196 patients seen by UKanQuit between Sept 1, 2007 and Aug 31, 2008 (426 accepted 6 months follow-up: Response rate 46%)

| Variables | |

|---|---|

| Smoking characteristics | |

| 7 day point prevalence abstinence rate, n (%) | 62 (31.8) |

| Among current smokers at 6 months follow up n=134 | |

| Proportion of smokers who attempted to quit within 6 months, n (%) | 99 (73.9) |

| Mean CPD for smokers at 6 months (SD) | 14.0 (9.7) |

| Used formal quit smoking program | |

| Quit smoking medication, n (%) | 65 (34.4) |

| Quit-line use among those faxed to quit line, n (%)* | 6 (5.0) |

| Importance/Confidence** | |

| How important is it to quit or stay quit, mean (SD) | 8.7 (2.3) |

| How confident are you to quit or stay quit, mean (SD) | 6.6 (3.6) |

| Views about service | |

| Satisfaction with UKanQuit service, mean (SD) | 8.3 (2.8) |

| Wants the UKanQuit program to continue, n (%) | 165 (97.6) |

For each variable, subsamples were slightly different from total sample due to missing data. Missing data were not included in the analysis.

Faxed to quit line n=121.

Importance/confidence, satisfaction with UKanQuit service range from 0–10

Satisfaction and recommendations for improvement

Most (96%) of participants contacted at follow-up commented on what was helpful about the services. Table 3 displays the distribution of themes and illustrative comments. Themes included staff encouragement, support and counseling (41.8%); other (27%); information and education materials (20.9%); medication advice and referral (2.6%) and referral to quit line (0.5%)

Table 3.

What was helpful about UKanQuit Services

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Staff encouragement, support and counseling “You guys did excellent. The friendliness of the people who visited me.” “Her outlook and her encouragement” |

82 (41.8) |

| Other “I don’t remember the visit because I was heavily medicated,” “A lot was helpful but I couldn’t tell you exactly what part was the most helpful” |

53 (27.1) |

| Information/education material “Provided me with a lot of info and the packet was helpful.” “The information packet” |

41 (20.9) |

| Program not helpful “I really didn’t need their information, I was able to quit without it.” “Nothing helpful except the companionship” |

14 (7.1) |

| Medication advice/referral “They took the time and set up the patches for me” “She helped me with questions about medication, especially Chantix” |

5 (2.6) |

| Referral to Quit line “Talking on the phone” |

1 (0.5) |

N= represents number of comments coded. Some of the comments fall within multiple domains and were so coded. “Other” included “don’t remember visit”, “Don’t know/not sure/Can’t think of anything”.

DISCUSSION

Among patients served by this inpatient program, interest in quitting was high but administration of in-patient medications upon admission was low (26%). Nearly all patients were provided with written materials, a majority set some form of goal for quitting or cutting down, and many developed quit plans and received assistance adjusting inpatient and/or discharge medications. After discharge, the majority of study participants made unassisted quit attempts, as utilization of medications and quitline services was suboptimal. Fax-referral to quitline may not, on its own, fulfill guideline recommendations for post-discharge follow-up.

Our intent-to-treat quit rate was about half of what was found in Taylor and colleagues’ hospital program dissemination trial.11 Their program may have had better effects as it was somewhat more intensive. It included at least one follow-up phone call immediately after discharge, as well as an accompanying video and relaxation audiotape or compact disk. However, differences in outcomes may also be due to large differences between the study populations. Hospitals participating in Taylor’s study only conducted intervention and outcome assessment among smokers who were ready to quit, willing to enroll in a clinical trial, and willing to complete informed consent. Our intervention and outcome data included patients who agreed to speak with UKanQuit staff, regardless of readiness to quit. Our participants did not have to complete informed consent and enroll in a trial as our analyses were conducted post-hoc. Our study outcomes might better reflect quit rates for a program serving all smokers, at all levels of readiness to quit, in actual hospital practices. The mean reduction in cigarette smoking among smokers who continued to smoke at 6 months’ follow up was statistically significant. However, findings from a lung health study show that 50% or more reduction in smoking was ultimately related to successful quitting.23

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the study include the fact that the program attempts to intervene with all smokers, and provides stage-appropriate intervention based on readiness to quit. It provides a snapshot of how a program is incorporated into clinical practice and describes implementation of protocol components.

This study has a number of limitations. We do not know exactly how many patients received the in-hospital medication change agreed upon by the counselor and medical team immediately following the patient encounter. Our follow-up rate was low and abstinence rates were based on self-report, which limits our ability to draw conclusions about cessation outcomes. Process of care measures are based on counselor self-report, without verification of services rendered. We are not able to identify the impact of our intervention above and beyond our patients’ hospital experience, because we did not have a control group. We collected limited data from study participants so we are not able to better understand causes of non-adherence to quitline or poor pharmacotherapy utilization. Last, when the respondents were asked to comment about what was helpful about UKanQuit, 23% of the respondents said they could not remember the UKanQuit visit during their hospital stay. Many hospital medications induce brief amnesia, and patients have numerous consults during their stay and might not be able to separate one from the other. The 6-month interval between their visit and follow up call may also account for their inability to remember the cessation consult.

Our patient population is in fact a subset of all smokers admitted (11% of smokers) because they are motivated enough to agree to talk with a counselor. Our intervention procedures, and results, might be quite different if all smokers were visited by the counselor. Efficacy trials of tobacco treatment in hospitals have focused on smokers who are ready to quit.24 Hence, procedures for working with unmotivated smokers in hospitals are less well established. Policymakers, hospitals, and hospital tobacco treatment programs should examine the most efficient (i.e., effective and cost-effective) approaches for addressing smoking in hospitals and specifically focus on whether all smokers should be treated by dedicated tobacco treatment staff, or only those who agree to a consult.

Lessons learned

Linking patients with in-hospital cessation medications requires collaboration with the entire health care team

Only one in four UKanQuit participants had been given smoking cessation medication to ameliorate withdrawal before counselors met with the patients. Although we have not systematically collected reasons patients do not receive cessation medication on admission, the two most common causes are that patients refuse it or physicians refuse it. Patients refuse medication perhaps because they do not want to quit, they feel they will cope without smoking during their hospital stay, or they are paying out of pocket and want to reduce costs. Physicians do not permit it because they believe it is contraindicated for the patient’s health condition, it is contraindicated for the procedure the patient is receiving in the hospital, or they believe it will interfere with wound healing. There is also a considerable delay between ordering and receiving medications; patients who become uncomfortable during their stay sometimes change their minds but end up being discharged before their medication arrives. Most of these issues pertain to nicotine replacement. Although patients not eligible for NRT may be good candidates for bupropion, varenicline, or even the second line cessation medications of clonidine or nortryptiline, these medications do not provide immediate relief from tobacco withdrawal symptoms and staff are reluctant to start patients on medications they may not receive on an outpatient basis. It is not clear what proportion of hospitalized patients should receive ameliorative medication. Not every hospitalized smoker is a candidate for NRT, due to contraindicated medical conditions, patients’ level of dependence, and patients’ willingness to accept cessation medication in order to prevent withdrawal. Koplan et al. achieved hospital-wide increases in NRT orders from 1.6% to 2.5% after the introduction of an electronic tobacco treatment order set.25 These percentages seem low but actually were calculated from all hospital admissions, including smokers and non-smokers. Moreover, their hospital population had a relatively low smoking rate of 12%. Our in-hospital and post discharge (26.2% and 34.4% respectively) pharmacotherapy utilization rates were based only on smokers who had been seen by our service. Even though 1 in 4 smokers were already on medication when they were seen by counselors, 1 in 4 of patients seen wanted to either add a cessation medication or change their current dose. There is clearly room for improvement in how we offer and administer cessation medications on admission. Also, assessing medication efficacy and adjusting as needed appears to be an important role for in-hospital counselors.

Facilitating medications post-discharge will require creativity and outpatient follow-up

Post-discharge, only 1 in 3 of our patients reported they used cessation medications. This may, again, be a function of patients’ readiness to quit. However, it could also be related to knowledge/attitudes regarding the efficacy of medications or access to low-cost medications. Some of our patients commented that making medication affordable would be helpful. Although our materials provide information on sources for free or low-cost medications, this information may not have been salient during the hospital stay. To increase access to medications post-discharge, programs should consider providing a booster mailer to the home with information on sources for free or reduced medications, providing take-home starter pharmacotherapy kits lasting one to two weeks to bridge the gap between hospital discharge and finding another source of medications, and/or a follow up call shortly after discharge to verify use of pharmacotherapy and troubleshoot problems with medications or procurement.

Providing follow-up via fax referral to quitlines is not as simple as it seems

Although our overall quitline fax-referral rate was high (over half of all patients seen), rate of enrollment among those referred is much lower than the rates reported elsewhere, which range from 16%–53%.26–28 In our sample of fax-referred smokers, we do not know how many were not enrolled due to failure to make contact versus patient refusal once contact was made. One possible factor impacting enrollment rates is whether or not smokers are pre-screened for readiness to quit. Nearly half of U.S. quitlines require smokers to be ready to quit in order to receive a full course of treatment29 but only 20% of smokers are ready to quit at any given time.30 In the cited studies with higher conversion rates, counselors pre-screened patients for readiness to quit and only offered fax-referral to those ready to quit in the next 30 days. Our program offers fax-referral to all smokers. Our findings suggest that doing so results in high rates of referral but low rates of enrollment among those referred. Future studies should examine the impact of pre-screening for readiness versus offering referral to all smokers on net enrollment and cessation.

Linking hospitalized smokers with tobacco quitlines has many potential benefits.31, 32 Proactive tobacco quitlines are effective15 and cost effective33 for smoking cessation; they are available, free, to all U.S. smokers; services are delivered via telephone which minimizes many access barriers; hospitals do not have to bear the costs of the services; and many quitlines are undersubscribed and eager to increase their reach.34 Potential methods for increasing conversion to enrollment include building motivation to accept counseling and preparing patients for the quitline intake procedures. Our program is considering providing a warm handoff to patients by calling the quitline during the bedside consult to permit the quitline to enroll the patient during their hospital stay.

Hospital-based cessation programs have the potential to deliver tobacco treatment to millions of hospitalized smokers annually. To deliver high-quality, effective care, hospital cessation programs will have to solve problems inherent in hospital-based care how best to integrate into existing hospital systems, how to effectively communicate with other hospital care providers, and how to facilitate transitions in care to ensure patients receive evidence-based post-discharge care. We offer this report as the first of hopefully many that address quality improvement for specialized programs dedicated to treating tobacco in hospitals.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the UKanQuit care process

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram showing enrollment and follow-up completion

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the following UKanQuit Counselors in the planning and development of this manuscript: Brian Hernandez, Alex Perez-Estrada, Grace Meikenhous, Meredith Benson, Terri Tapp. We also want to thank Chip Hulen, Albers Bart and Chris Wittkopp of the Organizational Improvement Department of KU Hospital; Marilyn Painter, Joanne McNair and Karisa Deculus of the KU Preventive Medicine and Public Health Department. This work was performed at the University of Kansas Medical School, Kansas City, Kansas with support from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA091912). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

This work was performed at the University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kansas.

References

- 1.Emmons KM, Goldstein MG. Smokers who are hospitalized: A window of opportunity for cessation interventions. Preventive Medicine. 1992;21:262–269. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90024-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res. 2003 Apr;18(2):156–170. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McBride CM, Ostroff JS. Teachable moments for promoting smoking cessation: the context of cancer care and survivorship. Cancer Control. 2003 Jul–Aug;10(4):325–333. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orleans CT, Kristeller JL, Gritz ER. Helping hospitalized smokers quit: New directions for treatment and research. J of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1993;61(5):778–789. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.5.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Oct 13;168(18):1950–1960. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.18.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD001837. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001837.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CDC. Physician and other health-care professional counseling of smokers to quit--United States, 1991. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993 Nov 12;42(44):854–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hollis JF, Bills R, Whitlock E, Stevens VJ, Mullooly J, Lichtenstein E. Implementing tobacco interventions in the real world of managed care. Tob Control. 2000;9 (Suppl 1):I18–24. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_1.i18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freund M, Campbell E, Paul C, et al. Smoking care provision in hospitals: a review of prevalence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008 May;10(5):757–774. doi: 10.1080/14622200802027131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawood N, Vaccarino V, Reid KJ, Spertus JA, Hamid N, Parashar S. Predictors of smoking cessation after a myocardial infarction: the role of institutional smoking cessation programs in improving success. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Oct 13;168(18):1961–1967. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.18.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor CB, Miller NH, Cameron RP, Fagans EW, Das S. Dissemination of an effective inpatient tobacco use cessation program. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005 Feb;7(1):129–137. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith PM, Reilly KR, Houston Miller N, DeBusk RF, Taylor CB. Application of a nurse-managed inpatient smoking cessation program. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002 May;4(2):211–222. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solberg LI, Kottke TE, Conn SA, Brekke ML, Calomeni CA, Conboy KS. Delivering clinical preventive services is a systems problem. Ann Behav Med. 1997 Summer;19(3):271–278. doi: 10.1007/BF02892291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solberg LI, Brekke ML, Fazio CJ, et al. Lessons from experienced guideline implementers: attend to many factors and use multiple strategies. The Joint Commission journal on quality improvement. 2000 Apr;26(4):171–188. doi: 10.1016/s1070-3241(00)26013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.USDHHS. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: Clinical Practice Guideline 2008 Update. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faseru B, Yeh H, Ellerbeck EF, Befort CA, Richter KP. Referral and Treatment for Nicotine Dependence among Hospitalized patients. Subst Abus. 2009 Jan–Mar;30 (1):94–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faseru B, Yeh HW, Ellerbeck EF, Befort C, Richter KP. Prevalence and predictors of tobacco treatment in an academic medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009 Nov;35(11):551–557. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35075-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991 Sep;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center TTUR, Workgroup TDP, Baker TB, et al. Time to first cigarette in the morning as an index of ability to quit smoking: Implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(1 supp 4):555–570. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.West R, Ussher M. Is the ten-item Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (QSU-brief) more sensitive to abstinence than shorter craving measures? Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010 Feb;208(3):427–432. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1742-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986 Mar;43(3):289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. Bmj. 2000 Jan 8;320(7227):114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes J, Lindgren P, Connett J, Nides M. Smoking reduction in the Lung Health Study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004 Apr;6(2):275–280. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001676297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rigotti N, Munafo M, Stead L. Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalised patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD001837. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001837.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koplan KE, Regan S, Goldszer RC, Schneider LI, Rigotti NA. A computerized aid to support smoking cessation treatment for hospital patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Aug;23(8):1214–1217. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0610-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bentz CJ, Bayley KB, Bonin KE, Fleming L, Hollis JF, McAfee T. The feasibility of connecting physician offices to a state-level tobacco quit line. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Jan;30(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willett JG, Hood NE, Burns EK, et al. Clinical faxed referrals to a tobacco quitline: reach, enrollment, and participant characteristics. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Apr;36(4):337–340. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cupertino A, Garrett S, Richter K, Ellerbeck E, Cox L. Feasibility of a Spanish/English Computerized Decision Aid to Facilitate Smoking Cessation Efforts in Underserved Communities. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0307. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. [Accessed March 19, 2010];North American Quitline Consortium. Web site: http://www.naquitline.org/

- 30.Velicer WF, Fava JL, Prochaska JO, Abrams DB, Emmons KM, Pierce JP. Distribution of smokers by stage in three representative samples. Prev Med. 1995;24:401–411. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stead LF, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD002850. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borland R, Segan CJ. The potential of quitlines to increase smoking cessation. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006 Jan;25(1):73–78. doi: 10.1080/09595230500459537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu SH, Anderson CM, Tedeschi GJ, et al. Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers. N Engl J Med. 2002 Oct 3;347(14):1087–1093. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids Fact Sheets. [Accessed on June 1, 2010];Quitlines Help Smokers Quit. 2008 Website: http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/research/factsheets/pdf/0326.pdf.