SUMMARY

The general Transcription Factor IID is a key player in the early events of gene expression. TFIID is a multisubunit complex composed of the TATA Binding Protein and at least thirteen TBP Associated Factors (TAfs) which recognize the promoter of protein coding genes in a activator dependant way. This review highlights recent findings on the molecular architecture and dynamics of TFIID. The structural analysis of functional transcription complexes formed by TFIID, TFIIA, activators and/or promoter DNA illuminates the faculty of TFIID to adjust to various promoter architectures and highlights its role as a platform for preinitiation complex assembly.

INTRODUCTION

Transcription is a highly regulated process that is intimately involved in all aspects of cellular activity, and allows cells to respond to a variety of signaling pathways particularly those controlling cell differentiation and development [1,2]. De novo initiation of transcription requires a set of multiprotein factors to assemble on the promoter of protein coding genes to form a preinitiation complex (PIC), which will ultimately convert RNA polymerase II from a transcriptionally inert form into a highly processive elongating form. Among the six basal transcription factors (TFIIA, B, D, E, F, H) and RNA polymerase II (Pol II) required to form the PIC, TFIID is crucial both for promoter recognition and interaction with transactivators. This review will highlight recent reports describing structural properties of TFIID and their functional implications.

1. Evolving roles of TFIID

First discovered as a multisubunit complex acting positively on pol II transcription, TFIID contains TBP and 13 associated proteins (Tafs) [3,4]. Early studies, using model promoters, showed that TBP recognizes the consensus TATA sequence element found 25 bp upstream of the transcription start site with nanomolar affinity. These findings were revisited by genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments that showed that TFIID is predominantly found on TATA-less promoters, whereas the related SAGA complex, which shares 5 subunits with TFIID, appears to deliver TBP to TATA-containing promoters [5]. In the absence of the TATA element, several evolutionarily-conserved TFIID subunits such as Taf2 [6] and the Taf4–Taf12 heterodimer [7] were shown to contribute to promoter recognition. Conserved promoter motifs that may contact specific TFIID subunits were described in Drosophila [8]; the evolutionary conservation of such elements throughout eukaryotes remains a subject of investigation [9].

TFIID has been implicated as a possible `writer' and `reader' of the chromatin epigenetic program through the Histone Acetyl Transferase (HAT) domain and double bromodomain (BRD) of Taf1 [10,11]. Additionally, the Taf3 subunit contains a metazoan-specific PHD finger domain, a motif capable of binding methylated lysine 4 of histone H3 [12]. It has been argued that these histone code readers and writers could play integral roles in recognition of promoter DNA in the context of chromatin.

Interestingly, TFIID does not appear to be required for all transcription initiation events since knockdown of TFIID subunits does not arrest transcription [13]. This phenomenon was recently confirmed by the knockdown of Taf10 in mice hepatocytes, which results in the disassembly of TFIID and blocks embryonic liver development yet strikingly has little effect on adult hepatocytes in which the transcription of ≤5% of genes were affected[14]. In this system it was found that while TFIID is required for initial gene transcription activation, a mediator-containing complex is sufficient for all subsequent transcription reinitiation events. Consistently it has been observed that the loss of specific Taf function, while often having a limited effect on overall gene transcription, always affects a defined subset of genes [15]. Collectively these observations indicate that each Taf plays a different role in mediating transcription on different classes of promoters but does not explain why the knockdown of structural Tafs such as Taf5 or Taf10 does not affect all genes [16].

Finally, in addition to its well-characterized role in promoter recognition, TFIID also plays key roles in transcription by virtue of its ability to act as a transcriptional coactivator. TFIID can serve as a bridge or receptor of signals from enhancer-bound transcriptional activator proteins [17]. A large array of transactivator proteins have been shown to physically and functionally interact with TFIID. However, exactly how these physical interactions result in the stimulation of PIC formation and/or function is only poorly understood. One popular model posits that activator-TFIID interaction drives TFIID recruitment, which leads to increased promoter binding and hence PIC formation. Whether this is a universal mechanism of TFIID coactivator action is unclear.

2. Atypical subunit composition of TFIID

TBP and the 13 Tafs that compose TFIID are conserved in all eukaryotes. Whereas in Saccharomyces cerevisiae the subunit composition of TFIID was found to be unique [18] metazoans have developed multiple strategies to form different TFIID complexes [19,20]. Tissue specific Taf and TBP paralogues can incorporate into TFIID and partial TFIID complexes have been identified which ensure tissue or cell specific transcription profiles or signaling pathways [21–23]. Nine Tafs contain a sequence motif homologous to histones, the histone fold domain (HFD). When appropriate pairs of HFD-containing Tafs are expressed in vitro, they form five specific heterodimers: Taf3–10, Taf6–9, Taf4–12, Taf8–10 and Taf11–13 [24]. The atomic structures of several of the unique HFD heterodimers have been determined and confirm the overall homology to histone folds. In these nine Tafs the sequences outside of the histone fold display considerable variation between species. With the exception of the metazoan-specific PHD domain in Taf3 and a proline-rich region in Taf8 no conserved region or homology domain could be identified. Thus it is likely that the non-HFD sequences in these Tafs are poorly structured and belong to the Intrinsically Unfolded Protein (IUP) class of proteins. The N-terminal region of Taf1 contains a conserved motif dubbed the TAND, or TAF N-terminal Domain, which is able to block DNA from contacting the concave DNA binding surface of TBP by adopting a TATA-DNA mimetic structure [25]. As mentioned above Taf1 also contains a HAT domain and, in metazoans, a double BRD. Three conserved domains have been identified in Taf5: the N-terminal LisH and NTD2 domains and six WD40 repeat found near the C-terminus. Finally the first 530 residues of Taf2 show a strong homology to leukotriene A4 hydrolase, an aminopeptidase of the M1 protease family.

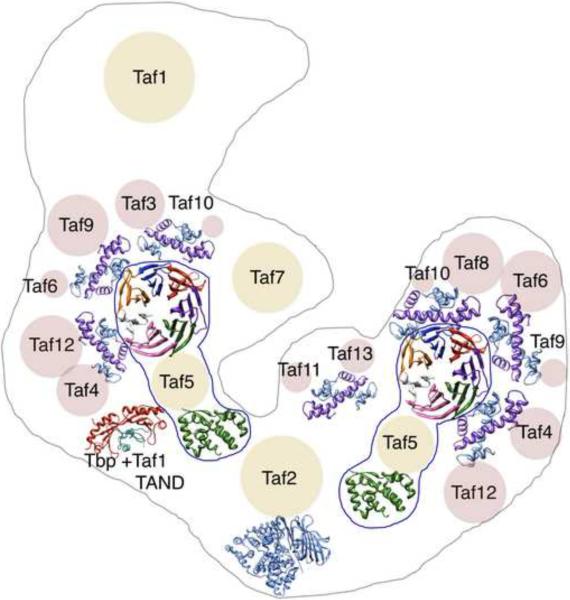

An often-overlooked property of TFIID is that Tafs are present in either one or two copies. Biochemical, genetic and immuno-electron microscopy experiments have independently shown that Taf5, 12, 4, 6, 9 and 10 are present in two copies whereas the other Tafs are most probably present as single copies. [18,26,27]. Taken together, a total of seven HFD-containing Taf pairs are thus likely to be present in TFIID (Fig.1). This stoichiometry suggests an internal two-fold symmetry involving six subunits composed of two copies of Taf5 and HFD-containing heterodimers of Taf6–9, Taf4–12 and Taf10. Symmetry is most likely broken by the recruitment of two possible partners for Taf10: Taf 8 and Taf3. Interestingly 5 of these 6 symmetry-related subunits (Taf5, 6–9, 10, 12) are shared with SAGA, in which Taf10 and Taf12 have different partners, an may constitute a common structural core.

Figure 1.

Subunit composition of yeast TFIID The known atomic structures of Taf domains or their homology models are shown along with a bulky representation of the non crystallized parts of the Tafs as circles whose sizes are proportional to the length of the remaining aminoacid chains. Circles representing histone-fold containing Tafs are colored pink. The different subunits were roughly positioned according to the available protein-protein interaction data and immunolabelling results. The atomic structures shown represent a characteristic HFD heterodimers for Taf4-12, Taf6-9 Taf10-8, Taf11-13 and Taf10-3; the structure of TBP complexed with the TAND domain of Taf1, the Leukotriene A4 hydrolase domain homologuous to Taf2; a characteristic WD40 propeller domain found in Taf5 and the NTD2 domain of Taf5.

3. A flexible architecture for TFIID

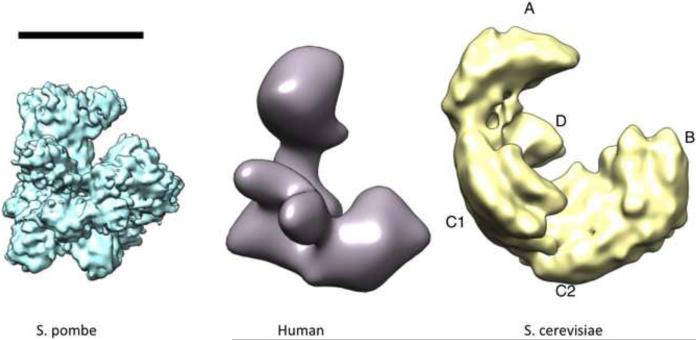

Atomic structures of several Taf domains and of TBP have been solved by X-ray diffraction (Fig.1) but high-resolution structures of the entire TFIID complex are still lacking. The molecular architecture of the complete TFIID complex has been investigated trough single molecule imaging by electron microscopy and early experiments on human TFIID revealed, at 35Å resolution, a multi-domain horseshoe-shaped assembly that resembles a molecular clamp [28,29]. Improvement in resolution was achieved for human and S. cerevisiae TFIID to around 20Å by preserving the hydrated state of the particles and by using advanced image analysis methods that sort out different conformations and/or structural variants; the major limitation to reach higher resolution [30,31]. The two models have a similar size of about 210–220 Å and a modular structure composed of the several lobes that collectively form the `clamp' (Fig.2). Minor differences between these two structures are likely due to the unique sizes of the constituent subunits. Recently a surprisingly high-resolution map (8–10Å) of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe TFIID was reported [32]. However, the size of these particles appears significantly smaller, and more roundish, suggesting either that the organization of TFIID is different in S. pombe, or that the authors stabilized a particular conformation of TFIID.

Figure 2.

Cryo electron microscopy models of TFIID. Comparison of the TFIID models derived from from Schizosaccharomyces pombe [32], Saccharomyces cerevisiae [30] and human [31]. The lobes were labeled according to the S. cerevisiae structure and may be different for the other models. The deposited S. pombe density map appeared significantly smaller and was rescaled according to the published size. The bar represents 10 nm.

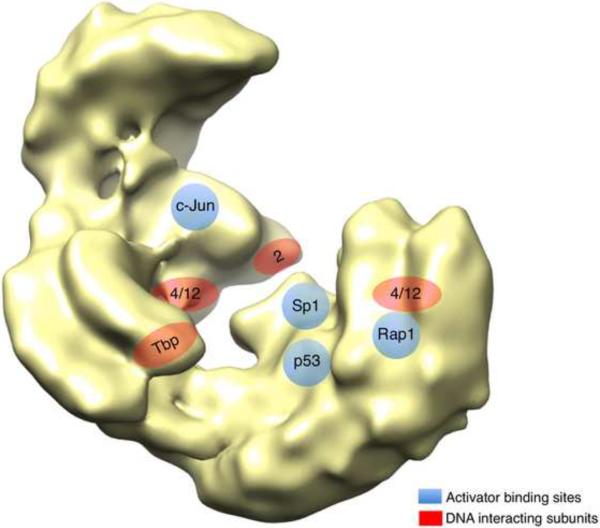

The resolution obtained thus far for the structure of TFIID is not sufficient to unambiguously fit the existing atomic resolution data and Tafs, which to date have been localized using antibody labeling. In human and S. cerevisiae, TBP was mapped almost in the center of the TFIID clamp and in good agreement with the position of the Taf1 TAND motifs responsible for TBP inhibition (Fig.3). Taf2 was mapped in the D-lobe and since it was shown to contact the Inr motif in some gene promoters the relative positions of Taf2 and TBP likely trace a path for promoter DNA across the clamp. In the context of the holo-TFIID complex the HFD-containing Tafs all appear as heterodimers, consistent with the assembly specificity defined in vitro. Several groups found Taf4/Taf4b in lobe C1 close to TBP [27,32,33] but in the case of S. cerevisiae Taf 4 was also found in lobe B consistently with the presence of two Taf4 copies. Consequently two models have been proposed for the organization of the Tafs present in two copies depending on whether a Taf4/12 hetrotetramer or a Taf5 dimer dominates the two-fold axis that organizes the other Tafs.

Figure 3.

Mapping functional sites on TFIID. The positions of Taf subunits involved in DNA contacts are represented in red and the transcriptional activator binding sites are depicted in blue on the yeast TFIID. The positions of the human activator binding sites were inferred from the alignment of the yeast and human TFIID models.

TFIID is a highly flexible structure, and systematic analyses have revealed constitutive conformational breathing of its different domains [31]. This property is likely to be important to allow TFIID to compensate for variable distances between activator binding sites and the transcription start site on those genes upon which it subserves a coactivator role. Large conformational changes were also observed in S. cerevisiae TFIID, particularly in forms of the complex deficient in the Taf2 subunit [30]. A structural reorganization was also detected in S. pombe and attributed to TBP binding [18,32]. Upon incorporation of the ovarian specific Taf4b TFIID was shown to adopt a slightly more open state, which might alter both promoter recognition and activator dependant transcription thus providing an explanation for the differential gene expression pattern driven by the c-Jun transactivator [31,33].

4. Functional complexes for PIC assembly

Recent experiments extended our understanding on the DNA recognition modalities by TFIID. TFIID requires TFIIA to recognize specifically the TATA element in the promoter and the role of TFIIA is to alleviate the inhibition due to the interaction of Taf1 TAND domains with the DNA binding surface of TBP. The interaction of TFIID with the promoter DNA was studied in the presence of TFIIA and image analysis revealed that TFIIA interacts close to TBP as predicted by the TBP-TFIIA-DNA crystal structure [34–36]. DNA was also detected in the C-terminal domain of Taf2, consistently with the documented interaction of this domain with the Inr sequence close to the transcription start site. The path of DNA coincides with the location of one of the Taf4-12 heterodimers which have been implicated in promoter DNA recognition [7].

To exert its coactivator function TFIID was shown in many systems to directly contact transactivators [37]. Several recent studies that have examined the molecular details of transactivator-TFIID interactions are particularly illuminating in this context; either interactions between human p53, Sp1 and c-Jun with human TFIID [38], or yeast Rap1 with yeast TFIID [34,39]. Sp1, p53, and c-Jun are among the most extensively studied metazoan transactivators that work via direct interaction with TFIID. The interaction of human TFIID with the three different transactivators was investigated both biochemically and structurally [38], and the authors reached two major conclusions. First, in contrast with the data obtained in the analysis of Mediator-transcription factor interaction [40], TFIID does not undergo significant conformational changes upon activator binding. Second, the three activators contacted different locations on the surface of TFIID, preferentially in lobe B but also in lobe A (Fig.3). The structural analyses were confirmed by transcription factor-TFIID Taf cross-linking experiments.

In the yeast system, transcription of ribosomal protein-encoding genes requires TFIID and the DNA-binding transactivator Rap1. Rap1 was shown to directly bind the TFIID complex through a network of interactions with Taf4, -5, and -12. The Rap1 binding domains (RBDs) of Taf4 and Taf5 have been characterized and are essential for cell viability but do not contribute to Taf-Taf interactions or TFIID stability [39]. Cryo electron microscopy revealed that Rap1 binds to lobe B away from TBP, which is located at the junction of A and C lobes. This structural data thus support the model that Taf4-12 heterodimers are present in two different lobes of TFIID, and that their environment is different. Notably, again, transactivator (Rap1) binding to yeast TFIID did not materially alter the structure of the holo-TFIID complex.

In order to extend these studies, and to obtain deeper insights into PIC formation, function and transcriptional activation mechanisms the structures of TFIID, activator and enhancer-promoter DNA, the structure of a committed activation complex formed between Rap1, TFIID and TFIIA, all assembled on a well characterized chimeric ribosomal enhancer promoter DNA fragment [41] was determined [34]. The resulting structure has shed new light on the intramolecular communication pathways conveying transcription activation signals through the TFIID coactivator. This study revealed an interaction between TFIIA and Rap1 that forms a protein bridge between TBP and the lobe B-bound Rap1. These interactions result in a large change in the position of TFIIA, and likely also TBP. While the exact role of this molecular switch is not fully understood; it was speculated that these conformational rearrangements could either: (a) stimulate an activator-dependant binding of TBP to the promoter; (b) stabilize the TFIID-promoter interaction since the protein bridge topologically traps the DNA; or (c) facilitate subsequent recruitment of TFIIB, Pol II and/or the additional components involved in PIC formation. Interestingly, concomitant binding of promoter to TFIID-bound Rap1 and to TBP/Taf2 loops out the intervening DNA thereby allowing the accommodation of variable distances between Rap1 binding sites and transcription start site. Future studies will further dissect the process of PIC formation while testing the above proposed models using additional biochemical, genetic and structural biology techniques.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

- 1.Ohler U, Wassarman DA. Promoting developmental transcription. Development. 2010;137:15–26. doi: 10.1242/dev.035493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *2.Venters BJ, Pugh BF. How eukaryotic genes are transcribed. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;44:117–141. doi: 10.1080/10409230902858785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This review gives a genome wide view of nucleosomal organization and transcription factor recruitment on gene promoters and aroud the transcription start site. The data shows how regulatory circuits of transcription factors are organized, how the chromatin is remodeled during preinitiation complex assembly and upon recruitment of RNA polymerase II.

- 3.Dynlacht BD, Hoey T, Tjian R. Isolation of coactivators associated with the TATA-binding protein that mediate transcriptional activation. Cell. 1991;66:563–576. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poon D, Weil PA. Immunopurification of yeast TATA-binding protein and associated factors. Presence of transcription factor IIIB transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:15325–15328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basehoar AD, Zanton SJ, Pugh BF. Identification and distinct regulation of yeast TATA box-containing genes. Cell. 2004;116:699–709. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00205-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verrijzer CP, Tjian R. TAFs mediate transcriptional activation and promoter selectivity. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:338–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gazit K, Moshonov S, Elfakess R, Sharon M, Mengus G, Davidson I, Dikstein R. TAF4/4b x TAF12 displays a unique mode of DNA binding and is required for core promoter function of a subset of genes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:26286–26296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.011486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juven-Gershon T, Kadonaga JT. Regulation of gene expression via the core promoter and the basal transcriptional machinery. Dev Biol. 2010;339:225–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang C, Bolotin E, Jiang T, Sladek FM, Martinez E. Prevalence of the initiator over the TATA box in human and yeast genes and identification of DNA motifs enriched in human TATA-less core promoters. Gene. 2007;389:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizzen CA, Yang XJ, Kokubo T, Brownell JE, Bannister AJ, Owen-Hughes T, Workman J, Wang L, Berger SL, Kouzarides T, et al. The TAF(II)250 subunit of TFIID has histone acetyltransferase activity. Cell. 1996;87:1261–1270. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81821-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson RH, Ladurner AG, King DS, Tjian R. Structure and function of a human TAFII250 double bromodomain module. Science. 2000;288:1422–1425. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5470.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **12.van Ingen H, van Schaik FM, Wienk H, Ballering J, Rehmann H, Dechesne AC, Kruijzer JA, Liskamp RM, Timmers HT, Boelens R. Structural insight into the recognition of the H3K4me3 mark by the TFIID subunit TAF3. Structure. 2008;16:1245–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report describes the details of the molecular recognition mechanism between the PHD domain of Taf3 and the trimethylated lysine 4 of histone H3. The atomic structure explains the binding specificity of TFIID to the post translationaly modified histone associated with actively transcribed genes.

- 13.Moqtaderi Z, Bai Y, Poon D, Weil PA, Struhl K. TBP-associated factors are not generally required for transcriptional activation in yeast. Nature. 1996;383:188–191. doi: 10.1038/383188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *14.Tatarakis A, Margaritis T, Martinez-Jimenez CP, Kouskouti A, Mohan WS, 2nd, Haroniti A, Kafetzopoulos D, Tora L, Talianidis I. Dominant and redundant functions of TFIID involved in the regulation of hepatic genes. Mol Cell. 2008;31:531–543. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report illustrates the diferent roles of TFIID in de novo transcription initiation, transcription reinitiation and transcripion repression. The authors show that while TFIID is required for the initiation of newly transcribed genes it is not for the maintenance of ongoing transcription.

- 15.Shen WC, Bhaumik SR, Causton HC, Simon I, Zhu X, Jennings EG, Wang TH, Young RA, Green MR. Systematic analysis of essential yeast TAFs in genome-wide transcription and preinitiation complex assembly. Embo J. 2003;22:3395–3402. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohtsuki K, Kasahara K, Shirahige K, Kokubo T. Genome-wide localization analysis of a complete set of Tafs reveals a specific effect of the taf1 mutation on Taf2 occupancy and provides indirect evidence for different TFIID conformations at different promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:1805–1820. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Alessio JA, Wright KJ, Tjian R. Shifting players and paradigms in cell-specific transcription. Mol Cell. 2009;36:924–931. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders SL, Garbett KA, Weil PA. Molecular characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae TFIID. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6000–6013. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.6000-6013.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller F, Zaucker A, Tora L. Developmental regulation of transcription initiation: more than just changing the actors. Curr Opin Genet Dev. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freiman RN. Specific variants of general transcription factors regulate germ cell development in diverse organisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1789:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deato MD, Marr MT, Sottero T, Inouye C, Hu P, Tjian R. MyoD targets TAF3/TRF3 to activate myogenin transcription. Mol Cell. 2008;32:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gazdag E, Santenard A, Ziegler-Birling C, Altobelli G, Poch O, Tora L, Torres-Padilla ME. TBP2 is essential for germ cell development by regulating transcription and chromatin condensation in the oocyte. Genes Dev. 2009;23:2210–2223. doi: 10.1101/gad.535209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolthur-Seetharam U, Martianov I, Davidson I. Specialization of the general transcriptional machinery in male germ cells. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:3493–3498. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.22.6976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gangloff YG, Sanders SL, Romier C, Kirschner D, Weil PA, Tora L, Davidson I. Histone folds mediate selective heterodimerization of yeast TAF(II)25 with TFIID components yTAF(II)47 and yTAF(II)65 and with SAGA component ySPT7. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1841–1853. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1841-1853.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotani T, Miyake T, Tsukihashi Y, Hinnebusch AG, Nakatani Y, Kawaichi M, Kokubo T. Identification of highly conserved amino-terminal segments of dTAFII230 and yTAFII145 that are functionally interchangeable for inhibiting TBP-DNA interactions in vitro and in promoting yeast cell growth in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32254–32264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leurent C, Sanders S, Ruhlmann C, Mallouh V, Weil PA, Kirschner DB, Tora L, Schultz P. Mapping histone fold TAFs within yeast TFIID. Embo J. 2002;21:3424–3433. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leurent C, Sanders SL, Demeny MA, Garbett KA, Ruhlmann C, Weil PA, Tora L, Schultz P. Mapping key functional sites within yeast TFIID. Embo J. 2004;23:719–727. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andel F, 3rd, Ladurner AG, Inouye C, Tjian R, Nogales E. Three-dimensional structure of the human TFIID-IIA-IIB complex. Science. 1999;286:2153–2156. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brand M, Leurent C, Mallouh V, Tora L, Schultz P. Three-dimensional structures of the TAFII-containing complexes TFIID and TFTC. Science. 1999;286:2151–2153. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Papai G, Tripathi MK, Ruhlmann C, Werten S, Crucifix C, Weil PA, Schultz P. Mapping the initiator binding Taf2 subunit in the structure of hydrated yeast TFIID. Structure. 2009;17:363–373. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report describes the frozen-hydrated structure of yeast TFIID and investigates the dynamics of the complex. The results show that in the absence of Taf2 the flexibility if the complex is increased.

- 31.Grob P, Cruse MJ, Inouye C, Peris M, Penczek PA, Tjian R, Nogales E. Cryo-electron microscopy studies of human TFIID: conformational breathing in the integration of gene regulatory cues. Structure. 2006;14:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elmlund H, Baraznenok V, Linder T, Szilagyi Z, Rofougaran R, Hofer A, Hebert H, Lindahl M, Gustafsson CM. Cryo-EM reveals promoter DNA binding and conformational flexibility of the general transcription factor TFIID. Structure. 2009;17:1442–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu WL, Coleman RA, Grob P, King DS, Florens L, Washburn MP, Geles KG, Yang JL, Ramey V, Nogales E, et al. Structural changes in TAF4b-TFIID correlate with promoter selectivity. Mol Cell. 2008;29:81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **34.Papai G, Tripathi MK, Ruhlmann C, Layer JH, Weil PA, Schultz P. TFIIA and the transactivator Rap1 cooperate to commit TFIID for transcription initiation. Nature. 2010;465:956–960. doi: 10.1038/nature09080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report gives the first structural insight into the early transcription initiation events on ribosomal protein gene promoters. It shows unexpected conformational changes of TFIIA induced by the Rap1 transactivator which promotes DNA loop formation during the early initiation steps.

- 35.Tan S, Hunziker Y, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Crystal structure of a yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Nature. 1996;381:127–151. doi: 10.1038/381127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geiger JH, Hahn S, Lee S, Sigler PB. Crystal structure of the yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Science. 1996;272:830–836. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burley SK, Roeder RG. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factor IID (TFIID) Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:769–799. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **38.Liu WL, Coleman RA, Ma E, Grob P, Yang JL, Zhang Y, Dailey G, Nogales E, Tjian R. Structures of three distinct activator-TFIID complexes. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1510–1521. doi: 10.1101/gad.1790709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; These results identified the interaction sites of three human trans-activators on TFIID and show that each activator binds to a distinct interaction surface within the complex.

- *39.Layer JH, Miller SG, Weil PA. Direct transactivator-transcription factor IID (TFIID) contacts drive yeast ribosomal protein gene transcription. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15489–15499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This report dissects the direct interaction of TFIID with the yeast transcriptional activator Rap1 and shows that several Tafs domains contribute to the interaction and are required in vivo for ribosomal protein gene transcription without affecting the structural integrity of TFIID.

- 40.Taatjes DJ, Naar AM, Andel F, 3rd, Nogales E, Tjian R. Structure, function, and activator-induced conformations of the CRSP coactivator. Science. 2002;295:1058–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.1065249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garbett KA, Tripathi MK, Cencki B, Layer JH, Weil PA. Yeast TFIID serves as a coactivator for Rap1p by direct protein-protein interaction. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:297–311. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01558-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]