Abstract

Purpose

Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) polymorphisms have been implicated as risk factors for coronary artery disease, but the results of genetic association studies on the related phenotype of ischemic stroke are inconclusive. We performed a meta-analysis of published studies investigating the association between ischemic stroke and two non-synonymous PON1 polymorphisms, rs662 (p.Q192R) and rs854560 (p.L55M) in humans.

Methods

We searched multiple electronic databases through 06/30/2009 for eligible studies. In main analyses we calculated allele-based odds ratios (OR) with random effects models. In secondary analyses we examined dominant and recessive genetic models as well, and performed subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

Results

Regarding rs662, we identified 22 eligible studies (total of 7384 cases/11,074 controls), yielding a summary OR of 1.10 per G allele (95% confidence interval, CI, 1.04–1.17) with no evidence of between-study heterogeneity. For rs854560, 16 eligible studies (total of 5518 cases/8951 controls) yielded a summary OR of 0.97 per T allele (95% CI, 0.90–1.04), again with no evidence of between-study heterogeneity. For both polymorphisms, analyses with dominant and recessive genetic models yielded the same inferences as allele-based comparisons. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses showed similar results.

Conclusion

In agreement with observations in coronary artery disease, PON1 rs662 appears to be associated with a small increase in the risk of ischemic stroke.

Keywords: paraoxonase 1, PON1, rs662, rs854560, stroke, meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

The paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene belongs to the paraoxonase gene cluster on 7q21.3–22 and codes for an enzyme with broad substrate specificity.1 The PON1 enzyme has lactonase and esterase activity and thus is able to catalyze the hydrolysis of lipid peroxides and organophosphate pesticides.1–2 Although its physiologic function has not been fully elucidated, the PON1 enzyme attaches to high-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles in serum, and has been shown to inhibit low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation, suggesting that PON1 may play a role in atherogenesis.2 Two non-synonymous PON1 polymorphisms with possible regulatory effects on enzyme activity2, namelyrs662 (c.575A>G or p.Gln192Arg) and rs854560 (c.163T>Aor p.Leu55Met), have been extensively investigated as potential risk factors for atherosclerosis-related phenotypes, including coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease and ischemic stroke.2–5

Two previously published systematic reviews suggested that the G allele of rs662 is associated with a small increase (per-allele OR=1.12) in the risk of coronary artery disease, while no such association was found for rs854560.4–5 Because cerebrovascular and coronary artery disease share many pathophysiologic mechanisms, it is plausible that rs662 could also be a risk factor for ischemic stroke.6–8 However, most published studies investigating the relationship between PON1 polymorphisms and ischemic stroke are small in sample size and inconclusive in their results. We therefore performed a meta-analysis to mitigate their shortcomings and summarize the totality of available published evidence on the association between the aforementioned PON1 polymorphisms and ischemic stroke.

METHODS

Search strategy

We searched the MEDLINE and SCOPUS databases, and the Human Genome Epidemiology Network Literature Finder (last search June 30th, 2009) to identify English-language studies investigating the association between the PON1 rs662 or rs854560 polymorphisms and ischemic stroke. Search terms included combinations of terms such as “paraoxonase”, “PON1”, “rs662”, “rs854560”, “Gln192Arg”, “Leu55Met”, “Q192R”, “L55M”, “stroke”, “cerebrovascular disease”, “cerebral infarction” and their synonyms. The exact search is available upon request by the authors. We did not consider other PON1 polymorphisms or polymorphisms in other members of the PON family of genes (PON2, PON3) because the available evidence on them is limited. We perused the reference lists of all retrieved articles and relevant reviews. We also searched the online archives of Stroke, Annals of Neurology and Cerebrovascular Diseases, three journals that have published several genetic association studies in ischemic stroke. Eligible studies were those that used case-control, nested case-control or cohort designs and validated genotyping methods to investigate the frequency of the two polymorphisms in unrelated ischemic stroke patients and unaffected individuals. We did not consider narrative reviews, editorials, and letters to the editor or other manuscripts not reporting primary research results. Family-based studies were excluded because their design and analysis is different from that of population association studies.

Data abstraction

One investigator abstracted detailed information from each publication regarding study design, matching and ascertainment of controls, demographics, ethnicity of participants (Caucasian continental ancestry, East Asian or other), definition of ischemic stroke, genotyping methods, disease stage, family history, and counts of genotypes and alleles in stroke cases and controls/unaffected individuals. We relied on the definitions used in each study to sub-classify stroke. When studies reported genotype distributions per stroke subtype, we also extracted data for each subtype separately, to use in subgroup analyses. We excluded from main analyses studies where patients with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke were merged together, but examined their impact on the meta-analysis results in sensitivity analyses.

Deviations from Hardy Weinberg equilibrium in the controls

For each study, we examined whether the distribution of the genotypes in the control group deviated from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) predicted proportions using an exact test.9 For studies that did not provide genotype counts, but reported allele frequencies only, we relied on the authors’ assessment of deviations from the HWE in the controls.

Meta-analysis

Main analyses compared allele frequencies of the variant and common allele (G versus A for rs662 and A versus T for rs854560) between cases and controls. We also evaluated dominant (variant allele carriers vs. homozygotes for the common allele) and recessive (homozygotes for the variant allele vs. all others) genetic models, for both polymorphisms. We used the odds ratio (OR) as a metric of choice. We calculated summary ORs and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) using the DerSimonian and Laird random effects model.10 We tested for between-study heterogeneity with Cochran’s Q statistic (considered statistically significant at p<0.10)and assessed its extent with theI2 statistic.11–12 I2 ranges between 0 and 100% and expresses the proportion of between study variability that is attributed to heterogeneity rather than chance. Larger I2 values imply more extensive heterogeneity.

Subgroup and sensitivity analyses

We performed pre-specified subgroup analyses by source of controls (healthy versus diseased), ethnicity, use of imaging to confirm the diagnosis of stroke, HWE in the control group and stroke subtype (atherothrombotic versus cardioembolic). We tested for “small-study effects” (differential magnitude of effects in large versus small studies)13 with the Harbord modification of the Egger test.14 These tests are often erroneously referred to as “publication bias tests”.13, 15 We used random effects meta-regression to compare the OR of the first study with the summary OR of subsequent studies or for comparisons between subgroups, as suggested elsewhere.16–17 We did not perform adjustments for deviations from the HWE in control genotypes because the necessary genotype counts were not available in a substantial number of studies.9, 18

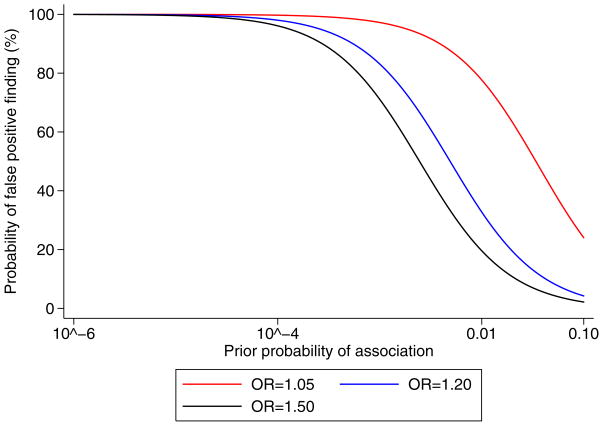

Assessing the probability of “false positive” findings

Associations with p-values less than 0.05 are conventionally referred to as “formally statistically significant”. Such associations can nevertheless be spurious (“false positives”), as the end result of chance or bias. Letting biases aside, the probability that a given formally significant result is a “false positive” increases with diminishing prior data in support of the association, decreasing (true) strength of the association, and decreasing statistical power to detect it.19–20 We calculated the probability that associations with p-values lower than 0.05 are “false” as suggested by Wacholder et al.19–20 To this end, we assumed that the true OR was 1.05(very small effect, similar to those detected in large meta-analyses of genomewide studies), 1.20 or 1.50 (modest effect, expected in most common diseases21) and that the prior probabilities of genuine association ranged from 10−8 (a conservative prior, akin to a variant of genomewide significance) to 0.10 (an indicator of strong prior support, appropriate for a functional polymorphism in a gene with strong biological plausibility).20 We considered probabilities of “false” association smaller than 0.20 indicative of an important finding.

Software

Analyses were performed using Stata (version 11/SE, Stata Corp., College Station, TX) and MetaAnalyst (version 3.0 beta, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, MA).22 For all tests, except those for heterogeneity, p-values were two-sided and statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. We did not perform any adjustments for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Literature flow

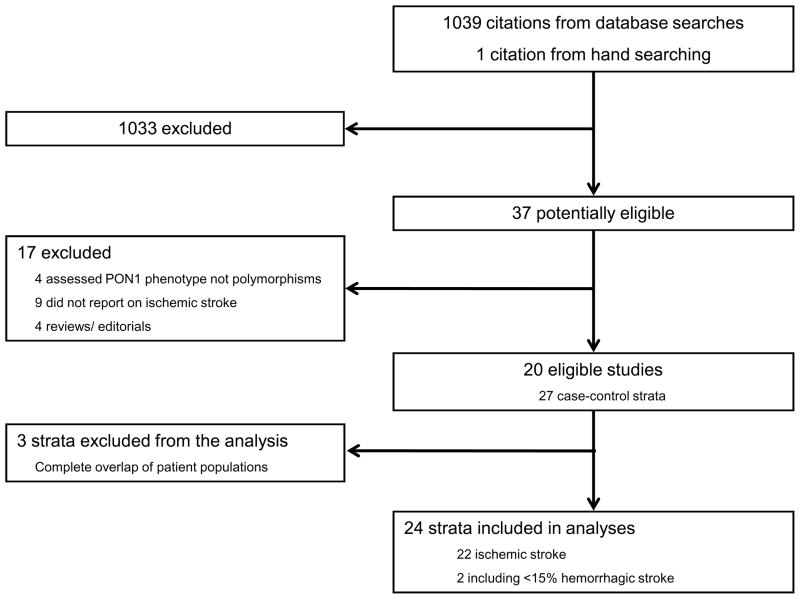

Our search identified 1039 citations of which 37 were considered potentially eligible and where retrieved in full text. Of those, 19 were excluded (four assessed PON1 activity but not genotypes, nine did not report on ischemic stroke, four were reviews/editorials, and two23–24 reported on overlapping populations with already included studies). Finally, 22 studies (i.e., 22 independent case-control strata) reported in 17 publications were eligible for the main analyses (Figure 1).23–39

Figure 1. Literature flow.

* Xu et al.39 reported information on 5 independent case-control groups which were considered as separate “studies” in the analyses.

** Wang at al.38 reported information on 5 independent case-control groups which were considered as separate “studies” in the analyses.

Study characteristics

Detailed study characteristics are presented in Table 1. All 22 studies (7384 cases/11,074 controls total) evaluated the rs662 variant and 16 of them (5518 cases/8951 controls total) reported genotyping for the rs854560 variant as well. Sample sizes ranged from 48 to 2092 (median 339). Eleven studies included populations of Caucasian,10 of East Asian and one of Hispanic descent. For most studies (n=16) there was no information on ischemic stroke subtypes. Three studies reported separate genotype distributions for atherothrombotic and cardioembolic strokes and three included only atherothrombotic strokes. The control groups in four studies for rs662 and one for rs854560 were not in HWE. Notably, only one study reported that genotyping was conducted blinded to the case/control status of participants and no study employed genotyping quality-control procedures.

Table 1.

Characteristics of eligible studies.

| Author, year | Ethnicity of participants | Cases | Controls | Control selection | Matching | Polymorphism(s) investigated | Genotyping method | HWE for rs662 | HWE for rs854560 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imai, 200029 | East Asian | 231 | 431 | Healthy, normal EKG, no Hx of CAD or stroke | None | rs662, rs854560 | PCR-RFLP | Yes | Yes |

| Topic, 200136 | Caucasian | 56 | 124 | Healthy volunteers | Age, sex | rs662 | PCR-RFLP | No | NA |

| Voetsch, 200223 | Hispanic | 118 | 118 | Blood donors or volunteers from the same geographical area as cases, no Hx of CVD | Age, sex, ethnic background | rs662, rs854560 | PCR-RFLP | No | Yes |

| Chen, 200339 | East Asian | 42 | 48 | NR | None | rs662 | NR | Yes | NA |

| Ueno, 200337 | East Asian | 112 | 106 | Healthy, no Hx of atherosclerotic disease | None | rs662, rs854560 | PCR-RFLP | No | Yes |

| Wu, 200539 | East Asian | 131 | 339 | NR | NR | rs662 | NR | Yes | NA |

| Yu, 200539 | East Asian | 1046 | 960 | NR | NR | rs662 | NR | Yes | NA |

| Aydin, 200625 | Caucasian | 65 | 84 | Healthy volunteers | None | rs662, rs854560 | PCR-RFLP | Yes | No |

| Baum, 200626 | East Asian | 242 | 310 | Randomly selected elderly without symptomatic vascular disease | None | rs662 | PCR-RFLP | Yes | NA |

| Chen, 200639 | East Asian | 109 | 339 | NR | NR | rs662 | NR | Yes | NA |

| Huang, 200628 | East Asian | 153 | 153 | Healthy individuals selected by random screening; individuals receiving lipid- lowering treatment or with family Hx of stroke were excluded | None | rs662, rs854560 | PCR-RFLP | Yes | Yes |

| Pasdar, 200631 | Caucasian | 397 | 405 | Individuals from the same geographic region as cases, without clinical CVD or CVAD | Age, sex | rs662, rs854560 | DASH | Yes | Yes |

| Schiavon, 200733 | Caucasian | 126 | 92 | Healthy volunteers; no Hx of stroke or CVAD | Age, sex | rs662, rs854560 | PCR-RFLP | Yes | Yes |

| Slowik, 200735 | Caucasian | 548 | 685 | Unrelated individuals from the population of South Poland with no neurological disease | Age of disease onset | rs662, rs854560 | PCR-RFLP | Yes | Yes |

| Can Demirdogen, 200827 | Caucasian | 108 | 78 | Symptom-free individuals from the same geographic area as cases; selected from the outpatient neurology clinics (<50% carotid stenosis) | None | rs662, rs854560 | PCR-RFLP | Yes | Yes |

| Shin, 200834 | East Asians | 350 | 242 | Individuals from the same geographic region as cases, without clinical CVD or CVAD disease | Age, sex | rs662, rs854560 | LightCycler melting curve | No | Yes |

| PHS, 200938 | Caucasian | 319 | 2092 | Case-control study nested within the PHS; all participants were initially free of MI, stroke, TIA and cancer; strokes were ascertained by medical record review | Age, smoking, time since study entry | rs662, rs854560 | Multilocus PCR | Yes | Yes |

| Pomerania, 200938 | Caucasian | 277 | 702 | Recruited randomly from the population based SHP study; selected after the administration of a stroke symptom questionnaire | Frequency matched for age and gender | rs662, rs854560 | Multilocus PCR | Yes | Yes |

| SHINING, 200938 | East Asian | 1163 | 1471 | Randomly selected individuals from the same geographic area as cases | Sex, birth year, geographic location and blood pressure group | rs662, rs854560 | Multilocus PCR | Yes | Yes |

| SOF, 200938 | Caucasian | 247 | 559 | Case-control study nested within SOF; controls were women who had not had bilateral hip replacement or earlier hip fracture at the time of recruitment | None | rs662, rs854560 | Multilocus PCR | Yes | Yes |

| Vienna study, 200938 | Caucasian | 844 | 979 | Volunteers in a health care program, no personal or first-degree family Hx of CVAD | None | rs662, rs854560 | Multilocus PCR | Yes | Yes |

| Westphalia, 200938 | Caucasian | 700 | 757 | Randomly selected participants from the population-based DHS study | None | rs662, rs854560 | Multilocus PCR | Yes | Yes |

Studies are listed by year of publication. CAD, coronary artery disease; CVD, cerebrovascular disease; CVAD, cardiovascular disease; DASH, Dynamic Allele Specific Hybridization; DHS, Dortmund Health Study; EKG, electrocardiogram; HWE, Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium; Hx, history; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PHS, Physicians’ Health Study; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism SHP, Study of Health in Pomerania; SOF, Study of Osteoporotic Fractures; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

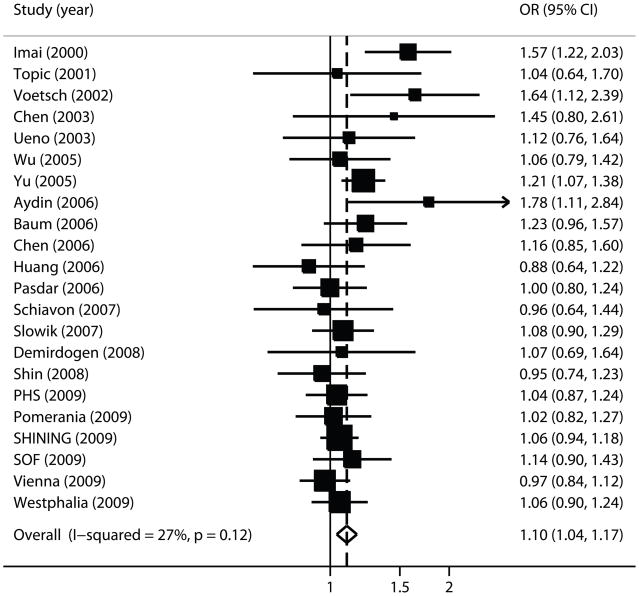

Meta-analysis of rs662

Figure 2 shows the forest plot for rs662. The summary random effects OR was 1.10 per G allele copy (95% CI, 1.04–1.17; p=0.001), with no evidence for statistical heterogeneity (pQ=0.12, I2=27%). The association remained significant under a dominant model (OR=1.31; 95% CI, 1.05–1.63; p=0.02) and a recessive model (OR=1.22; 95% CI, 1.05–1.43; p=0.01), with evidence of between-study heterogeneity in the dominant model (p<0.001, Table 2). These results remained unchanged in terms of magnitude and significance, when the two additional studies that included a minority of hemorrhagic strokes were also included (24 case-control strata, 8008 cases/13,810 controls; per-allele OR=1.12; 95% CI, 1.05–1.20; p=0.001), but there was evidence of between-study heterogeneity (p=0.02).

Figure 2. Forest plot of PON1 rs662 and ischemic stroke.

Meta-analysis of studies investigating the association of PON1 rs662 with ischemic stroke using a random effects model. Each study is shown by the point estimate of the odds ratio (square proportional to the weight of each study) and 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio (extending lines); the summary odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals by random effects calculations is depicted as a diamond. Values higher than 1 indicate that the G allele is associated with increased ischemic stroke risk.

Table 2.

Main analysis, subgroup and sensitivity analysis for studies investigating the association between PON1 rs662 and ischemic stroke risk.

| Summary | Allele-based (G vs A) | Dominant (GG + AG vs AA) | Recessive (GG vs AG + AA) * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies (alleles in cases/controls) | OR (95% CI); p-value | PQ (I2[%]) | Studies (cases/controls) | OR (95% CI); p-value | PQ (I2[%]) | OR (95% CI); p-value | PQ (I2[%]) | |

| All studies | 22 (7384/11/074) | 1.10 (1.04–1.17); 0.001 | 0.12 (27) | 15 (3437/4109) | 1.31 (1.05–1.63); 0.02 | <0.001 (65) | 1.22 (1.05–1.43); 0.01 | 0.14 (30) |

| Subgroup analyses | ||||||||

| Ethnic descent | ||||||||

| Caucasian | 11 (3687/6557) | 1.04 (0.98–1.12); 0.21 | 0.73 (0) | 5 (903/1063) | 1.12 (0.80–1.57); 0.52 | 0.06 (56) | 1.42 (1.03–1.96); 0.03 | 0.42 (0) |

| East Asian | 10 (3579/4399) | 1.14 (1.04–1.26); 0.01 | 0.10 (38) | 9 (2416/2928) | 1.42 (1.02–1.98); 0.04 | <0.001 (70) | 1.16 (1.00–1.35); 0.05 | 0.26 (21) |

| Control population | ||||||||

| Healthy | 15 (5459/8441) | 1.078 (0.99–1.17); 0.06 | 0.06 (40) | 9 (1759/2035) | 1.25 (0.94–1.67); 0.12 | 0.003 (66) | 1.32 (1.02–1.72); 0.04 | 0.15 (35) |

| Diseased | 7 (1925/2633) | 1.18 (1.08–1.29); <0.001 | 0.95 (0) | 6 (1678/2074) | 1.44 (0.96–2.16); 0.08 | 0.01 (66) | 1.15 (0.95–1.40); 0.16 | 0.23 (27) |

| HWE deviation in controls | ||||||||

| Yes | 4 (636/590) | 1.145 (0.89–1.47); 0.28 | 0.14 (46) | 4 (636/590) | 1.093 (0.82–1.46); 0.55 | 0.27 (24) | 1.19 (1.03–1.38); 0.02 | 0.25 (21) |

| No | 18 (6748/10484) | 1.10 (1.03–1.17); 0.002 | 0.14 (27) | 11 (2801/3519) | 1.42 (1.06–1.90); 0.02 | <0.001 (71) | 1.90 (0.84–4.27); 0.12 | 0.08 (60) |

| Imaging for diagnosis of stroke | ||||||||

| Yes | 19 (6762/8299) | 1.11 (1.04–1.19); 0.003 | 0.06 (37) | 14 (3381/3985) | 1.35 (1.07–1.70); 0.01 | <0.001 (66) | 1.21 (1.03–1.42); 0.02 | 0.13 (32) |

| No or NR | 2 (566/2651) | 1.07 (0.93–1.24); 0.32 | 0.54 (0) | 1 (56, 124) | 0.88 (0.47–1.65); 0.69 | NA | 2.33 (0.65–8.41); 0.195 | NA |

| Matching | ||||||||

| Yes | 9 (3354/5931) | 1.05 (0.98–1.13); 0.15 | 0.59 (0) | 5 (1198/1261) | 1.03 (0.88–1.21); 0.74 | 0.42 (0) | 1.61 (0.87–2.99); 0.13 | 0.08 (55) |

| No | 13 (4030/5143) | 1.15 (1.05–1.26); 0.003 | 0.07 (39) | 10 (2239/2848) | 1.55 (1.10–2.18); 0.01 | <0.001 (69) | 1.19 (1.04–1.36); 0.01 | 0.34 (11) |

| Stroke subtype | ||||||||

| Cardioembolic | 6 (1088/1299) | 1.19 (1.02–1.38); 0.03 | 0.24 (26) | 6 (1088/1299) | 1.25 (0.92–1.69); 0.15 | 0.03 (59) | 1.62 (1.01–2.62); 0.05 | 0.06 (56) |

| Atherothrombotic | 3 (332/612) | 1.34 (0.86–2.09); 0.19 | 0.08 (61) | 3 (332/612) | 1.56 (0.72–3.36); 0.26 | 0.06 (64) | 1.40 (0.85–2.29); 0.19 | 0.65 (0) |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||||||||

| Studies including HS | 2 (624/2736) | 1.38 (0.82–2.32); 0.22 | 0.01 (85) | 2 (624/2736) | 1.62 (0.74–3.58); 0.23 | 0.006 (87) | 1.28 (0.77–2.11); 0.35 | 0.24 (29) |

| All studies including those with HS | 24 (8008/13/810) | 1.12 (1.05–1.20); 0.001 | 0.02 (40) | 17 (4061/6845) | 1.35 (1.10–1.66); 0.005 | <0.001 (67) | 1.23 (1.06–1.41); 0.005 | 0.17 (25) |

| Excluding first study | 21 (7153/10643) | 1.08 (1.03–1.14); 0.002 | 0.42 (3) | 16 (3830/6414) | 1.28 (1.05–1.56); 0.02 | <0.001 (63) | 1.19 (1.00–1.41); 0.05 | 0.15 (29) |

| First study | 1 (231/431) | 1.57 (1.22–2.03); <0.001 | NA | 1 (231/431) | 3.17 (1.63–6.17); 0.001 | NA | 1.50 (1.09–2.06); 0.01 | NA |

HS: hemorrhagic strokes (less than 20 percent of strokes, see text); NA, not applicable; NR, not reported

Estimates do not include the study by Shin, 2008 because no homozygotes for the G allele of rs662 were identified in this study.14

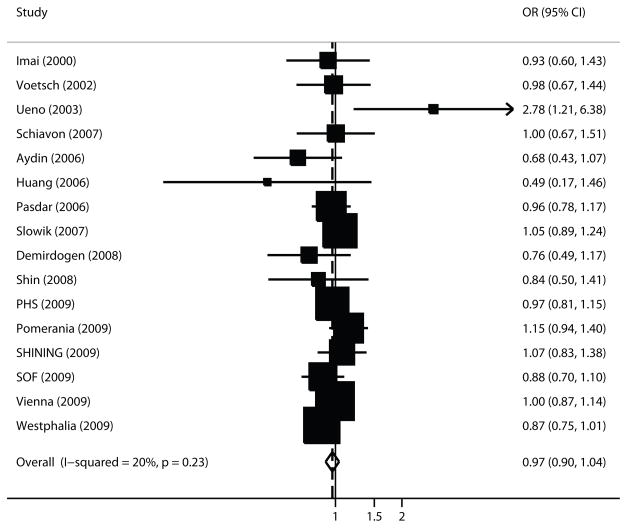

Meta-analysis of rs854560

Regarding rs854560, there was no evidence of an association with ischemic stroke risk (OR=0.97 per A allele copy; 95% CI 0.90–1.04; p=0.37)(Figure 3). Between-study heterogeneity was non-significant (p=0.23; I2=20%). Alternative genetic models also did not reveal evidence of an association (Table 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot of PON1 rs854560 and ischemic stroke.

Meta-analysis of studies investigating the association of PON1 rs854560 with ischemic stroke using a random effects model. Values higher than 1 indicate that the A allele is associated with increased ischemic stroke risk. Layout similar to Figure 1.

TABLE 3.

Main analysis, subgroup and sensitivity analysis for studies investigating the association between PON1 rs854560 and ischemic stroke risk.

| Summary | Allele-based analyses (A vs T) | Dominant (AA + AT vs TT) | Recessive* (AA vs AT +TT) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies (alleles in cases/controls) | OR (95% CI); p-value | PHet (I2[%]) | Studies (cases/controls) | OR (95% CI); p-value | PHet (I2[%]) | OR (95% CI); p-value | PHet (I2[%]) | |

| All studies | 16 (5518/8951) | 0.97 (0.90–1.04); 0.37 | 0.23 (20) | 9 (1815/1986) | 1.03 (0.88–1.20); 0.75 | 0.42 (1) | 0.69 (0.41–1.14); 0.14 | 0.03 (56) |

| Subgroup analyses | ||||||||

| Ethnic descent | ||||||||

| Caucasian | 10 (3387/6430) | 0.96 (0.90–1.03); 0.26 | 0.35 (10) | 4 (847/936) | 1.03 (0.85–1.25); 0.75 | 0.67 (0) | 0.65 (0.34–1.24); 0.19 | 0.01 (73) |

| East Asian | 5 (2013/2403) | 1.03 (0.74–1.44); 0.85 | 0.09 (51) | 4 (850/932) | 1.01 (0.61–1.66); 0.98 | 0.09 (53) | 1.31 (0.08–22.95); 0.85 | 0.12 (60) |

| Control population | ||||||||

| Healthy | 14 (5163/8314) | 0.98 (0.91–1.06); 0.66 | 0.22 (21) | 8 (1707/1908) | 1.05 (0.89–1.24); 0.57 | 0.41 (2) | 0.70 (0.38–1.28); 0.24 | 0.02 (62) |

| Diseased | 2 (355/637) | 0.851 (0.70–1.04); 0.11 | 0.56 (0) | 1 (108/78) | 0.77 (0.43–1.39); 0.39 | NA | 0.63 (0.28–1.41); 0.26 | NA |

| HWE deviation in controls | ||||||||

| Yes | 1 (65/84) | 0.68 (0.43–1.07); 0.10 | NA | 1 (65/84) | 1.38 (0.62–3.08); 0.43 | NA | 0.29 (0.13–0.62); 0.002 | NA |

| No | 15 (5453/8867) | 0.98 (0.91–1.04); 0.48 | 0.30 (14) | 8 (1750/1902) | 1.01 (0.85–1.21); 0.89 | 0.37 (8) | 0.92 (0.67–1.27); 0.62 | 0.37 (7) |

| Imaging for diagnosis of stroke | ||||||||

| Yes | 14 (4952/6300) | 0.98 (0.90–1.06); 0.59 | 0.16 (27) | 9 (1815/1986) | 1.03 (0.88–1.20); 0.75 | 0.42 (1) | 0.69 (0.41–1.14); 0.14 | 0.03 (56) |

| No or NR | 2 (566/2651) | 0.93 (0.81–1.07); 0.32 | 0.50 (0) | No studies | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Matching | ||||||||

| Yes | 8 (3054/5804) | 1.022 (0.94–1.11); 0.61 | 0.90 (0) | 4 (1142/1134) | 1.028 (0.86–1.24); 0.77 | 0.84 (0) | 1.01 (0.75–1.37); 0.93 | 0.41 (0) |

| No | 8 (2464/3147) | 0.90 (0.78–1.04); 0.15 | 0.08 (44) | 5 (673/852) | 1.05 (0.68–1.61); 0.83 | 0.12 (45) | 0.50 (0.22–1.16); 0.11 | 0.16 (43) |

| Stroke subtype | ||||||||

| Atherothrombotic | 5 (881/986) | 1.02 (0.79–1.30); 0.91 | 0.10 (48) | 5 (881/986) | 1.08(0.75–1.56); 0.69 | 0.05 (57) | 0.91 (0.64–1.28); 0.58 | 0.57 (0) |

| Cardioembolic | 2 (308/302) | 1.28 (0.82–2.00); 0.27 | 0.13 (56) | 2 (308/302) | 1.60 (0.60–4.26); 0.35 | 0.04 (76) | 1.28 (0.79–2.09); 0.32 | 0.95 (0) |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||||||||

| Excluding first study | 15 (5283/8520) | 0.97 (0.90–1.04); 0.41 | 0.18 (25) | 8 (1580/1555) | 1.03 (0.85–1.26); 0.74 | 0.33 (13) | 0.70 (0.41–1.21); 0.20 | 0.02 (62) |

| First study | 1 (235/431) | 0.93 (0.60–1.43); 0.73 | NA | 1 (235/431) | 0.98 (0.614–1.547); 0.91 | NA | 0.36 (0.04–3.14); 0.36 | NA |

Additional analyses

Overall, subgroup-analysis results were consistent with the main analyses. Tables 4 and 5 present meta-regression analyses for the study-level covariates that we investigated for rs622 and rs854560, respectively. Overall, the factors we explored did not significantly affect the effect size of the genetic associations investigated.

Table 4.

Meta-regression results for PON1 rs662. Significant results are presented in bold type.

| Allele-comparison | Dominant | Recessive | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative OR | Interaction p-value | Relative OR | Interaction p-value | Relative OR | Interaction p-value | |

| Ethnicity (East Asians versus Caucasians) | 1.09 (0.98–1.20) | 0.12 | 1.25 (0.66–2.38) | 0.49 | 0.82 (0.56–1.19) | 0.30 |

| Use of disease controls | 1.11 (0.99–1.25) | 0.07 | 1.15 (0.63–2.10) | 0.65 | 0.87 (0.63–1.20) | 0.40 |

| Control group in HWE | 0.98 (0.79–1.20) | 0.83 | 1.27 (0.68–2.39) | 0.46 | 0.74 (0.43–1.27) | 0.27 |

| Imaging for diagnosis of stroke | 1.03 (0.86–1.24) | 0.76 | 1.55 (0.48–5.00) | 0.46 | 1.39 (0.66–2.90) | 0.39 |

| Matching | 0.92 (0.82–1.04) | 0.17 | 0.71 (0.41–1.22) | 0.22 | 1.31 (0.85–2.03) | 0.23 |

| First study | 1.46 (1.12–1.89) | 0.005 | 2.61 (0.91–7.49) | 0.08 | 1.26 (0.80–1.97) | 0.32 |

HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; OR, odds ratio

Table 5.

Meta-regression results for PON1 rs854560. Significant results are presented in bold type.

| Allele-comparison | Dominant | Recessive | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Relative OR | Interaction p-value | Relative OR | Interaction p-value | Relative OR | Interaction p- value |

| Ethnicity (East Asians versus Caucasians) | 1.07 (0.84–1.37) | 0.57 | 1.11 (0.66–1.88) | 0.70 | 1.64 (0.19–14.19) | 0.65 |

| Use of disease controls | 0.87 (0.69–1.09) | 0.22 | 0.76 (0.43–1.35) | 0.36 | 0.90 (0.22–3.70) | 0.88 |

| Control group in HWE | 1.44 (0.87–2.38) | 0.15 | 1.48 (0.84–2.61) | 0.18 | 3.14 (1.24–7.96) | 0.02 |

| Imaging for diagnosis of stroke | 1.05 (0.88–1.25) | 0.59 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Matching | 1.11 (0.98–1.26) | 0.09 | 1.20 (0.85–1.68) | 0.30 | 2.05 (0.93–4.55) | 0.08 |

| First study | 0.95 (0.57–1.58) | 0.86 | 0.97 (0.52–1.80) | 0.92 | 0.51 (0.04–6.16) | 0.60 |

HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio

Figure 4 depicts the calculated probability of false association between rs622 and ischemic stroke(not applicable for rs854560 where an association was not found). The figure demonstrates that unless there is a strong prior belief in the association between rs622 and ischemic stroke, the probability that the association is a false positive finding is relatively high, for all possible ORs examined.

Figure 4. Probability of “false positive” association between PON1 rs622 and ischemic stroke.

Estimation of the probability of “false positive” association between rs622 and ischemic stroke plotted against a wide range of prior probabilities for a genuine association. Calculations as described in Wacholder et al. 2004.20 The dashed line indicates a threshold of a relatively low probability of “false positive” association, operationally set at 20%.

There was no evidence that smaller studies had systematically different results compared to larger studies (Harbord test p=0.14 for rs662 and p=0.75 for rs854560). For rs662, the OR of the first study (1.57, 95% CI, 1.22–2.03) was statistically significantly different and more extreme compared to the pooled OR of all subsequent studies (interaction test p=0.005). Omitting the first study reduced between study heterogeneity (pQ=0.42; I2=3%) and the association remained significant (OR=1.08; 95% CI, 1.03–1.14; p=0.002). Including versus excluding the first study resulted in no appreciable changes for rs854560.

DISCUSION

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies, we found a statistically significant association between the PON1 variant (arginine-encoding, G) allele at rs662 and ischemic stroke. The magnitude of this association is small, as expected for common variants and common diseases. In addition, we found no evidence for an association between rs854560 and the same phenotype. The meta-analyses results were robust in subgroup and sensitivity analyses; however, these analyses may not be powered to detect modest between-subgroup differences because of the relatively small number of studies per subgroup. Although there is a biologically plausible role for PON1 in the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke, we estimated that the probability of the association between rs662 and ischemic stroke being “false-positive” is relatively high for a wide range of assumptions.

The PON1 enzyme attaches to HDL particles and prevents LDL oxidation,1 and may therefore have a role in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease development.40–41 There is evidence that polymorphisms in the PON1 gene influence PON1 activity. Rs662 modifies PON1 enzymatic activity in a substrate-dependent manner, and rs854560 is in linkage disequilibrium with functional promoter polymorphisms.41–42 Yet, PON1 polymorphisms explain only a fraction of the variability in PON1 serum activity.2, 43–44 and it is likely that additional genetic and environmental influences contribute to the ischemic stroke phenotype.

The identified association between rs622 and ischemic stroke is consistent with the modest relationship between rs622 and coronary artery disease risk, which has a summary OR of 1.12 per G allele copy in recent meta-analyses of a different set of studies than those summarized here.4–5 Such congruent levels of risk for ischemic stroke and coronary artery disease conferred by the same variant have been also described for other genetic associations.45 The fact that these two correlated atherosclerotic phenotypes are associated with the rs622 variant has several alternative explanations.

First, it is possible that the associations of rs662 with both phenotypes are genuine and independent of each other, in which case further laboratory investigation is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms. Another possible explanation is that the rs622 variant primarily affects an intermediate or surrogate phenotype common to the pathophysiology of both coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke, such as dyslipidemia,34, 46 increased carotid intima-media thickness6, 46 or inflammation.47 If this is true, the direct effect of rs622 on the hypothesized intermediate phenotype is expected to be quite larger than the observed associations on the downstream clinical phenotypes of ischemic stroke and coronary artery disease (both around 1.10 per copy of G allele).

Conversely, it may be that only one of the associations is true or that both are spurious. If only one of the two phenotypes was truly associated with rs622, then the other would also appear to be associated as well, because coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke tend to occur together, i.e. they are correlated. However, in that case, the OR of the phenotype that is not independently associated with the PON1 genotype would be expected to be closer to the null(even for strong between-phenotype correlations).

The association of rs662 and ischemic stroke seems to be consistent with the “winner’s curse” phenomenon, where the first publication on a gene-disease association reports a spurious or exaggerated effect size that is not replicated by subsequent research.16 “Winner’s curse” may be the result of various selection biases such time-lag bias, shortcomings in the design and conduct of individual studies, or chance. Briefly, time lag bias exists when the order of study publication depends on study results, e.g., with statistically significant studies being published first, and non-significant studies published subsequently. In its extreme form, non-significant studies remain unpublished (publication bias). Publication bias likely exists in genetic and genomic topics, but cannot be measured directly. This is because most of the so-called “publication bias diagnostics” simply test for systematic differences between more and less precise studies, for which publication bias is only one of many possible explanations.13, 15

Further, although there are no validated quality characteristics to distinguish association studies with higher versus lower risk of bias, one can use criteria with substantial face validity. In our topic, only one study explicitly mentioned blinding of investigators to the case/control status of participants, no studies reported using genotyping quality control procedures, and in several studies the genotypic frequencies in the control groups deviated from those expected under HWE. Finally, as shown in Figure 4, the probability that the association is due to chance (“falsely” positive)is relatively high for a wide range of assumptions. It remains to be defined whether functional evidence on rs622 and pathophysiological evidence implicating PON1 in ischemic stroke are supportive of strong biological plausibility. In such case, further studies would be required to disentangle the mechanistic effects of this genetic variant and confirm the findings of our meta-analysis.

In conclusion, we found evidence of a weak association between rs662 and ischemic stroke risk, similar in magnitude to the corresponding association of the variant with coronary disease. Genetic variation in the paraoxonase gene cluster merits further investigation, preferably using haplotyping approaches to comprehensively assess its relationship with atherosclerotic disease risk and elucidate the molecular basis of the observed genetic effects.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grant U54 RR023562 to Tufts-Clinical Translational Science Institute. IJD is the recipient of a research fellowship provided by the “Maria P. Lemos” Foundation. GDK is a recipient of a Pfizer-Tufts Medical Center career development award.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Mackness MI, Arrol S, Durrington PN. Paraoxonase prevents accumulation of lipoperoxides in low-density lipoprotein. FEBS Lett. 1991;286:152–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80962-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackness M, Mackness B. Paraoxonase 1 and atherosclerosis: is the gene or the protein more important? Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roest M, Jansen AC, Barendrecht A, Leus FR, Kastelein JJ, Voorbij HA. Variation at the paraoxonase gene locus contributes to carotid arterial wall thickness in subjects with familial hypercholesterolemia. Clin Biochem. 2005;38:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wheeler JG, Keavney BD, Watkins H, Collins R, Danesh J. Four paraoxonase gene polymorphisms in 11212 cases of coronary heart disease and 12786 controls: meta-analysis of 43 studies. Lancet. 2004;363:689–695. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawlor DA, Day IN, Gaunt TR, et al. The association of the PON1 Q192R polymorphism with coronary heart disease: findings from the British Women’s Heart and Health cohort study and a meta-analysis. BMC Genet. 2004;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humphries SE, Morgan L. Genetic risk factors for stroke and carotid atherosclerosis: insights into pathophysiology from candidate gene approaches. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:227–235. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00708-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrison AC, Bare LA, Luke MM, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with coronary heart disease predict incident ischemic stroke in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;26:420–424. doi: 10.1159/000155637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luke MM, Lalouschek W, Rowland CM, et al. Polymorphisms associated with both noncardioembolic stroke and coronary heart disease: vienna stroke registry. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:499–504. doi: 10.1159/000236914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trikalinos TA, Salanti G, Khoury MJ, Ioannidis JP. Impact of violations and deviations in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium on postulated gene-disease associations. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2006;163:300–309. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochran W. The Combination of Estimates from Different Experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:101–129. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Schmid CH, Olkin I. The case of the misleading funnel plot. Bmj. 2006;333:597–600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.333.7568.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JA. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Statistics in medicine. 2006;25:3443–3457. doi: 10.1002/sim.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Terrin N, Schmid CH, Lau J. In an empirical evaluation of the funnel plot, researchers could not visually identify publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:894–901. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ioannidis JP, Ntzani EE, Trikalinos TA, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Replication validity of genetic association studies. Nature genetics. 2001;29:306–309. doi: 10.1038/ng749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knapp G, Hartung J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat Med. 2003;22:2693–2710. doi: 10.1002/sim.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salanti G, Higgins JP, Trikalinos TA, Ioannidis JP. Bayesian meta-analysis and meta-regression for gene-disease associations and deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Stat Med. 2007;26:553–567. doi: 10.1002/sim.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas DC, Clayton DG. Betting odds and genetic associations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:421–423. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wacholder S, Chanock S, Garcia-Closas M, El Ghormli L, Rothman N. Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:434–442. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA, Khoury MJ. Implications of small effect sizes of individual genetic variants on the design and interpretation of genetic association studies of complex diseases. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:609–614. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wallace BC, Schmid CH, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Meta-Analyst: software for meta-analysis of binary, continuous and diagnostic data. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Voetsch B, Benke KS, Damasceno BP, Siqueira LH, Loscalzo J. Paraoxonase 192 Gln--> Arg polymorphism: an independent risk factor for nonfatal arterial ischemic stroke among young adults. Stroke. 2002;33:1459–1464. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000016928.60995.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voetsch B, Benke KS, Panhuysen CI, Damasceno BP, Loscalzo J. The combined effect of paraoxonase promoter and coding region polymorphisms on the risk of arterial ischemic stroke among young adults. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:351–356. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aydin M, Gencer M, Cetinkaya Y, et al. PON1 55/192 polymorphism, oxidative stress, type, prognosis and severity of stroke. IUBMB Life. 2006;58:165–172. doi: 10.1080/15216540600688462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baum L, Ng HK, Woo KS, et al. Paraoxonase 1 gene Q192R polymorphism affects stroke and myocardial infarction risk. Clin Biochem. 2006;39:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Can Demirdogen B, Turkanoglu A, Bek S, et al. Paraoxonase/arylesterase ratio, PON1 192Q/R polymorphism and PON1 status are associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke. Clin Biochem. 2008;41:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang Q, Liu YH, Yang QD, et al. Human serum paraoxonase gene polymorphisms, Q192R and L55M, are not associated with the risk of cerebral infarction in Chinese Han population. Neurol Res. 2006;28:549–554. doi: 10.1179/016164106X110337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imai Y, Morita H, Kurihara H, et al. Evidence for association between paraoxonase gene polymorphisms and atherosclerotic diseases. Atherosclerosis. 2000;149:435–442. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lansbury AJ, Catto AJ, Carter AM, Bamford JM, Grant PJ. The Paraoxonase Glutamine/Arginine Polymorphism and Cerebrovascular Disease. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;7:353–355. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pasdar A, Ross-Adams H, Cumming A, et al. Paraoxonase gene polymorphisms and haplotype analysis in a stroke population. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ranade K, Kirchgessner TG, Iakoubova OA, et al. Evaluation of the paraoxonases as candidate genes for stroke: Gln192Arg polymorphism in the paraoxonase 1 gene is associated with increased risk of stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:2346–2350. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185703.88944.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schiavon R, Turazzini M, De Fanti E, et al. PON1 activity and genotype in patients with arterial ischemic stroke and in healthy individuals. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116:26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin BS, Oh SY, Kim YS, Kim KW. The paraoxonase gene polymorphism in stroke patients and lipid profile. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;117:237–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2007.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slowik A, Wloch D, Szermer P, et al. Paraoxonase 2 gene C311S polymorphism is associated with a risk of large vessel disease stroke in a Polish population. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23:395–400. doi: 10.1159/000101462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Topic E, Simundic AM, Ttefanovic M, et al. Polymorphism of apoprotein E (APOE), methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and paraoxonase (PON1) genes in patients with cerebrovascular disease. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2001;39:346–350. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2001.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ueno T, Shimazaki E, Matsumoto T, et al. Paraoxonase1 polymorphism Leu-Met55 is associated with cerebral infarction in Japanese population. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:CR208–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, Cheng S, Brophy VH, et al. A meta-analysis of candidate gene polymorphisms and ischemic stroke in 6 study populations: association of lymphotoxin-alpha in nonhypertensive patients. Stroke. 2009;40:683–695. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.524587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu X, Li J, Sheng W, Liu L. Meta-analysis of genetic studies from journals published in China of ischemic stroke in the Han Chinese population. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;26:48–62. doi: 10.1159/000135653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jarvik GP, Rozek LS, Brophy VH, et al. Paraoxonase (PON1) phenotype is a better predictor of vascular disease than is PON1(192) or PON1(55) genotype. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2441–2447. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brophy VH, Jampsa RL, Clendenning JB, McKinstry LA, Jarvik GP, Furlong CE. Effects of 5′ regulatory-region polymorphisms on paraoxonase-gene (PON1) expression. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1428–1436. doi: 10.1086/320600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen J, Chan W, Wallenstein S, Berkowitz G, Wetmur JG. Haplotype-phenotype relationships of paraoxonase-1. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:731–734. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thyagarajan B, Jacobs DR, Jr, Carr JJ, et al. Factors associated with paraoxonase genotypes and activity in a diverse, young, healthy population: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Clin Chem. 2008;54:738–746. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.099044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rainwater DL, Rutherford S, Dyer TD, et al. Determinants of variation in human serum paraoxonase activity. Heredity. 2009;102:147–154. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2008.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bentley P, Peck G, Smeeth L, Whittaker J, Sharma P. Causal relationship of susceptibility genes to ischemic stroke: comparison to ischemic heart disease and biochemical determinants. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carlson CS, Heagerty PJ, Hatsukami TS, et al. TagSNP analyses of the PON gene cluster: effects on PON1 activity, LDL oxidative susceptibility, and vascular disease. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1014–1024. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500517-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fan AZ, Yesupriya A, Chang MH, et al. Gene polymorphisms in association with emerging cardiovascular risk markers in adult women. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]