Abstract

Health disparities are, to a large extent, the result of socio-economic factors that cannot be entirely mitigated through the health care system. While an array of social services are thought to be necessary to address the social determinants of health, budget constraints, particularly in difficult economic times, limit the availability of such services. It is therefore necessary to prioritize interventions through some fair process. While it might be appropriate to engage in public deliberation to set priorities, doing so requires that the public accept such a deliberative process and appreciate the social determinants of health. We therefore analyzed the results of a study in which groups deliberated to prioritize socio-economic interventions to examine whether these two requirements can possibly be met and to explore the basis for their priorities. A total of 431 residents of Washington, D.C. with incomes under 200% of the federal poverty threshold participated in 43 groups to engage in a hypothetical exercise to prioritize interventions designed to ameliorate the social determinants of health within the constraints of a limited budget. Findings from pre- and post-exercise questionnaires demonstrate that the priority setting exercise was perceived as a fair deliberative process, and that following the deliberation, participants became more likely to agree that a broad number of determinants contribute to their health. Qualitative analysis of the group discussions indicate that participants prioritized interventions that would provide for basic necessities and improve community conditions, while at the same time addressing more macro-structural factors such as homelessness and unemployment. We conclude that engaging small groups in deliberation about ways to address the social determinants of health can both change participant attitudes and yield informed priorities that might guide public policy aimed at most affordably reducing health disparities.

Keywords: USA, public participation, interventions, health priorities, health status disparities, public assistance, poverty, resource allocation

Introduction

Solid evidence of health disparities has served to focus attention on approaches to promote health equity (Williams, 2007). While adequate access to quality health care is essential, it is not entirely sufficient to achieve this goal because health status is also heavily influenced by socioeconomic factors (World Health Organization, 2008). Even in countries with well-established systems of universal health care, a health gradient persists in association with socioeconomic position (Bratu, Martens, Leslie, Dik, Chateau, & Katz, 2008; Marmot, 1999; Steptoe, Hamer, O'Donnell, Venuraju, Marmot, & Lahiri, 2010). Although there is debate about the mechanisms relating income and health and disagreement about whether the steepness of the gradient matters, there is agreement that position on the socioeconomic gradient is closely tied to health and well being (House, 2001; Kawachi & Blakely, 2001).

In order to address the social conditions that underlie health disparities, social epidemiologists have argued that a broad array of structural changes are needed. The WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health has recommended that social action should aim to address the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age; and that this be accomplished by tackling the “upstream drivers” of those conditions, specifically the inequitable distribution of power, income, and resources (WHO, 2008). A number of the specific recommendations of the Commission aimed at promoting equity, such as fair labor laws, gender equity, and political empowerment, require social change – changes in policies, regulations and attitudes -while others require more financial resources in order to fund services such as education and training programs.

Several countries have led the way by developing multifaceted approaches that aim to decrease inequalities in health by making improvements in housing, education, employment, transportation, and neighborhood environment, in addition to health care (Acheson D, 1998; Heymann, 2006; The Standing Committee on Social Affairs Science and Technology, 2009). In times of economic hardship, however, budget deficits are likely to threaten the fulfillment of many recommendations that are the most resource intensive, such as essential social services (Johnson, Oliff, & Williams, 2009). The most disadvantaged segments of the population become even more susceptible to ill health and financial insecurity (Laszlo, Pikhart, Kopp, Bobak, Pajak, Malyutina et al., 2010; Seguin, Xu, Gauvin, Zunzunegui, Potvin, & Frohlich, 2005; Seligman, Laraia, & Kushel, 2010). It therefore becomes increasingly important to prioritize interventions so that the most needed services continue to receive funding and a social safety net remains in place.

In recent years there has been substantial emphasis on the importance of public participation in priority setting and decisions regarding resource allocation in health care (Mitton, Smith, Peacock, Evoy, & Abelson, 2009). However, there has been much less work done in priority setting regarding the broader array of services aimed at addressing the social determinants of health. Engaging the public in prioritizing such services is particularly challenging since the public, particularly in the U.S., lacks awareness of the determinants of health and health inequalities. A random sampling of Wisconsin adults found that when asked to rate factors that affect people's health, respondents emphasized individual health behaviors and health insurance as the most important factors (Robert, Booske, Rigby, & Rohan, 2008). This research suggests that in order to be successful, any plan designed to engage the public in addressing the social determinants of health must have an educational component that increases the public understanding of the many factors that affect health.

Democratic deliberation serves as a proven method to promote public understanding and ascertain public views (Abelson, Eyles, McLeod, Collins, McMullan, & Forest, 2003a; Fishkin, 1997). It offers the promise of enhancing public awareness of the concepts inherent in social epidemiology and gleaning public priorities with regard to them. There are several practical examples of how deliberation has been used to engage the public in policy decisions including deliberative polling, citizens' juries, and national issues forums (Gastil & Levine, 2005). Through these approaches, a representative sample of individuals are educated about an issue and come together as equals in order to discuss the issue as a group, present divergent opinions, and resolve disagreements in a respectful atmosphere. Gutmann and Thompson (2000) describe deliberation as “a process of mutual reason-giving” which provides a justifiable and acceptable decision and encourages a public mindedness perspective (Gutmann & Thompson, 2000). This process has been demonstrated to create a more informed and engaged public with views that have been transformed by a deeper understanding of the issues being addressed (Abelson, Forest, Eyles, Smith, Martin, & Gauvin, 2003b; Dolan, Cookson, & Ferguson, 1999; Luskin, Fishkin, & Jowell, 2002). In addition, participatory processes may go even further to lend greater legitimacy to policy decisions and provide for an accountability that increases public trust (Goodin & Dryzek, 2006; Lenaghan, 1999). Yet when deliberative processes have been pursued to promote public understanding of social epidemiology, these efforts have not demonstrably enhanced public appreciation of the social determinants of health (Abelson 2003a, Luskin 2002).

With this in mind, a research study was undertaken to engage low income urban residents in a deliberative exercise aimed at fostering appreciation of the social determinants of health and ascertaining participant priorities regarding interventions to address the social determinants of health. This study was a joint collaboration of the National Institutes of Health, Howard University, and the District of Columbia Department of Health. The combined quantitative and qualitative analysis reported here examines the following questions: 1.Was the process a successful deliberation? 2. Did the process increase participant understanding of the determinants of health? 3. What are the views of the participants elicited during deliberation regarding the services that should be prioritized to address the socioeconomic determinants of health?

Methods

Identification and cost estimation of intervention options

Interventions offered in this priority setting exercise took into account significant determinants of health including medical care, health behavior, environmental conditions, and social and economic factors. Interventions were chosen based on a review of the literature as well as consideration of existing U.S. government and private sector programs. The costs of interventions were estimated by researching existing programs deemed to be similar in scope. Adjustments were made to reflect any differences in design between existing services and the service described in the exercise, and costs were further adjusted to give estimates appropriate for the year in which the study was being conducted (Milliman Inc., 2007). A description and estimated cost of the final list of 16 interventions, as explained to study participants, can be found in Table 1. (M Danis, Kotwani, Garrett, Rivera, Davies-Cole, & Carter-Nolan, 2010b)

Table 1.

Simplified Benefit Descriptions and Monthly Costs

| EDUCATION | |

| Adult Education | |

| You can get money to finish high school. You can get up to 80% of the cost of college courses or professional courses at a community college. You will keep getting money if you pass your courses. | $ 82.23 |

| Childhood Education | $110.65 |

| Your child can go to pre-school or kindergarten. This will help your child to get ready for school. Older children in low-performing schools can go to after-school programs. | |

| English language and literacy training | $ 35.86 |

| Adults and children who do not speak English at home can learn to speak, read, and write in English. | |

|

| |

| EMPLOYMENT | |

| Job Training | $ 27.03 |

| You will receive job training which will help you perform your job better. You will learn skills that may help you keep your job. These new skills may help you move to another job or get promoted. | |

| Job Placement Programs | $ 46.33 |

| You will receive help to apply for a job. You will learn skills that help you to be a better employee. | |

| Day Care for Working Parents | $58.16 |

| Your child can get free or low cost day-care if your child is younger than 13. Teenagers can go to after school programs until they are 16. Your children can also go to summer school. | |

|

| |

| HEALTH AND DENTAL CARE | |

| Health Insurance | $413.00 |

| This health insurance package will cover the cost of medical care and medicines. | |

| Dental Care | $ 29.00 |

| This insurance plan will pay for routine dental care. | |

| Counseling Programs | |

| You can get counseling for drug, alcohol, anger, stress, and gambling problems. Mentors for young people will help them stay in school. The mentors will help kids to stay away from drugs, crime, and unsafe sex. | $ 14.00 |

|

| |

| HOUSING | |

| You will get vouchers to pay for rent or your mortgage. You may also get some money to help you buy a house or repair your home. | $ 77.00 |

|

| |

| TRANSPORTATION | |

| You will get a voucher to pay for traveling to work on public buses or trains. | $ 46.00 |

|

| |

| NUTRITION | |

| Grocery Store Incentives | $ 9.00 |

| There will be more grocery stores near your home so you can buy healthy food. | |

| Food Stamps | $244.00 |

| Low income families will get electronic cards. They can use these cards to buy healthy food at some grocery stores. Poor women, babies, and children younger than five will get healthy foods. They will also learn about healthy eating and receive health care. | |

| School Meals | $ 28.00 |

| Your school age children will receive free or cheaper breakfast and lunch at school. | |

|

| |

| NEIGHBORHOOD IMPROVEMENT | |

| Parks, bike trails, and play areas will be built near your home. Kids and adults can exercise safely in these areas. | $ 9.00 |

|

| |

| HEALTHY BEHAVIOR | $ 26.00 |

| You enroll in programs that help you to be healthy. These programs will help you lose weight, reduce your blood pressure, or quit smoking. You will get to choose other benefits or get money for staying in these programs. | |

|

| |

| TAXED INCOME SUPPLEMENT | Variable |

Participants

Residents of Washington, D.C. were recruited through English and Spanish newspaper advertisements and flyers displayed at local businesses and doctors' offices. Residents were eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 65 with a personal income or household income at or below 200% of the federal poverty threshold for 2006. U.S. Federal poverty guidelines are available at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website at http://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/06poverty.shtml. While guidelines vary greatly between nations making comparisons difficult, 200% of the U.S. poverty threshold is approximately 60 percent of the national median income, which is the poverty rate used by the United Kingdom and the European Union (Smeeding, 2006). This threshold was used because it selects for a segment of the population that is greatly affected by decisions regarding social services.

The group discussions were conducted in English and in Spanish between January and May of 2008. English language groups met in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at Howard University College of Medicine; Spanish language groups met at two federally qualified health centers in Washington, D.C.

Deliberative Exercise

To engage participants and elicit their priorities we used a paper version of the Reaching Economic Alternatives that Contribute to Health (REACH) exercise (M Danis et al., 2010b; M. Danis, Lovett, Sabik, Adikes, Cheng, & Aomo, 2007). This exercise was designed to facilitate public engagement in prioritization of interventions and is based on a well validated decision tool called Choosing Healthplans All Together that was originally designed to elicit public priorities regarding health insurance benefits (M. Danis, Biddle, & Dorr Goold, 2002; Goold, Biddle, Klipp, Hall, & Danis, 2005). Participants were told that the purpose of the exercise was to compose a hypothetical benefit package of social programs intended to have an impact on health. At the beginning of the exercise, participants were given the following simple explanation about the socio-economic determinants of health and their relationship to health disparities:

Around the world public health experts have learned that people with low incomes are likely to be less healthy than people with high incomes. There are lots of reasons for this. People with low incomes often have less education. They don't earn as much money to spend on medical care and other things they need to keep them healthy. They live in neighborhoods and houses that are less safe. The project you are participating in today was created to address this problem. Several governments are developing programs to improve the health of people with low incomes. They offer programs that help people to improve their lives and their health. But these programs are very expensive and it will be hard for any government to offer all the programs that might possibly be helpful. Today we will ask you to imagine that your city is planning programs to improve the health of low-income residents. Today you get a chance to tell us which programs would be most helpful to you. You get to say which programs you would recommend for the city. We have given you an information booklet to help you learn how programs can affect your health. We hope you will use this information as you make your choices. We know, for example, that eating a healthy diet is good for your health. So if the city offered to make sure that good grocery stores were available in your neighborhood, it might be good for your health. If the city offered you safe parks where you could exercise, it might be good for your health. If the city offered to pay for school for you to learn a new skill you might be able to get a higher paying job. This might be good for your health. Perhaps this is because you would be under less financial stress. Feel free to choose benefits as you wish. We hope that the information about health will help you make your decisions. As you get a chance to pick programs today, we hope to learn from you what matters to you most.

Participants were also given an information booklet describing the interventions that they could read at any time throughout the entire exercise. This booklet was written in English and Spanish at the 6th grade reading level, and individuals who had difficulty reading the booklet were given individual assistance. (These materials are available from the authors upon request.)

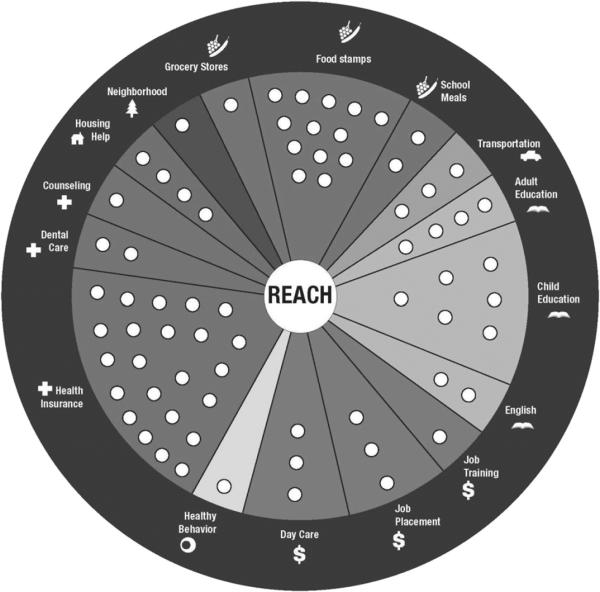

During the exercise participants were given 50 markers valued at $18 each. This totaled $885 per month, which is approximately double the estimated Medicaid benefit for enrollees who are under 65. The rationale for using this dollar amount was so participants could compose a hypothetical package of benefits that included the usual medical care, along with a package of socio-economic interventions that are equivalent in cost to traditional health care. We did not specify or address possible sources of funds since the deliberative exercise was intended to focus on priorities for apportionment of funds rather than sources of funding. The relative cost of each intervention was rounded to the nearest $18 so that the 16 interventions, including health coverage, were estimated to have a total value of $1,256 per month (Milliman Inc., 2007). Thus participants were able to fund approximately 70% of the available interventions ($885/1256), a manageable proportion for a priority setting exercise. Participants chose interventions by placing their markers on a pie-shaped exercise board that displayed all of the possible options (Figure 1). All of the spaces within an intervention had to be covered with markers to select that intervention. Participants were given the option to forgo assigning any number of markers to receive a hypothetical taxable income subsidy instead.

Fig. 1.

REACH Exercise Board.

The exercise consisted of four rounds of prioritizing. In the first round participants were instructed to make choices individually in order to design a benefit package for themselves and their immediate family. The second round was designed to allow for practice in deliberation and participants worked in groups of 3 to design a benefit package for a neighborhood. The third round, which was the basis of the qualitative analysis provided here, was designed to allow participants to deliberate as an entire group to choose a package of program benefits for the city. Group discussion was facilitated and participants each took turns nominating and justifying interventions. Participants were encouraged to express their opinions without interruption, and questions were asked only to clarify information presented. Participants discussed each recommendation, giving reasons for agreeing or disagreeing with them. Subsequently a benefit was selected either by consensus or, failing that, by majority vote. These discussions were audiotaped for qualitative analysis.

In the fourth round, participants once again made a benefit package for themselves and their family to ascertain changes in individual priorities that occurred during the course of the exercise. Between each decision making round, participants read aloud and discussed randomly selected “life event” cards. There were approximately 6 life event cards created for each intervention, and each card described a scenario along with the possible outcomes that could result from choosing or forgoing a specific intervention.

Prior to the start of the exercise, questionnaire items were administered to ascertain socio-demographic characteristics, health characteristics, and use of publicly funded services and income tax credit. Participants were also asked about their level of agreement with several statements to gauge their views about determinants of health, such as “my health depends on my neighborhood.” Participants indicated their level of agreement using a five point Likert scale ranging from 1 for “strongly disagree” to 5 for “strongly agree.” Participants were again asked their level of agreement with these statements following completion of the exercise in order to ascertain whether their views on the determinants of health had changed. In addition, participants were queried about their level of agreement with statements regarding the REACH exercise to assess their experience with the deliberative process. All questionnaire items were based on measures that have been previously used and validated (M. Danis et al., 2007; Goold et al., 2005).

Human Subjects Protection

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the National Institute for Child Health and Development at the National Institutes of Health, Howard University, and the Washington, D. C. Dept. of Health. Signed informed consent was obtained from every study participant at the outset of each group session.

Data preparation and analysis

Audiotapes of the group discussions were transcribed verbatim. Those exercises that were conducted in Spanish were translated into English and then transcribed. Transcripts were imported into the software program NVivo which allowed for electronic coding. Codes were derived inductively from the transcripts without a preliminary template so as to best understand participants and accurately represent their stated views. Overarching themes were identified and a coding frame was developed based on these themes. In order to best capture why certain interventions were chosen over others, the coding scheme focused on intervention-specific justifications for inclusion and exclusion. The transcripts were then independently coded by two researchers and compared for agreement. The analysis and coding frame was refined and confirmed through discussions with the entire research team.

The statistical analyses for the questionnaire responses were performed using the statistical package Stata version 10. Participant characteristics, group choices from the third round, as well as frequency and degree of agreement with evaluation statements regarding the REACH exercise and the determinants of health were examined using descriptive statistics. For the statements concerned with determinants of health, a two tailed paired t-test was used to compare the level of agreement before and after the exercise.

Results

Forty-three groups, including 31 conducted in English and 12 conducted in Spanish, consisting of 431 low-income urban individuals, participated in deliberations using the REACH exercise. Groups ranged in size from 5 to 14 individuals. The mean age of participants was 45 years; 61 percent of participants were female, and the majority identified themselves as either African American (57%) or Latino (34%). Participant demographics can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Study Participants (N = 431)

| Characteristic | N | Mean (SD) or Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 4271 | 45.1 (11.6) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 165 | 38.3 |

| Female | 262 | 60.4 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White (non-Latino) | 7 | 1.6 |

| Black (non-Latino) | 246 | 57.1 |

| Latino | 148 | 34.3 |

| American Indian / Native Alaskan | 7 | 1.6 |

| Asian | 1 | 0.2 |

| Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.2 |

| Other (non-Latino) | 19 | 4.4 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.5 |

| Insurance Source (select all that apply) | ||

| No health insurance | 45 | 10.4 |

| Work place insurance | 45 | 10.4 |

| DC alliance2 | 118 | 27.4 |

| Medicare | 85 | 19.7 |

| Medicaid | 154 | 35.7 |

| VA or military | 12 | 2.8 |

| Student insurance | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other health insurance source | 20 | 4.6 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single, never married | 189 | 43.9 |

| Married | 84 | 19.5 |

| Partnered | 28 | 6.5 |

| Separated | 45 | 10.4 |

| Divorced | 58 | 13.5 |

| Widowed | 24 | 5.6 |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.7 |

| Financial Dependents | ||

| No dependents | 126 | 29.2 |

| One | 94 | 21.8 |

| Two | 60 | 13.9 |

| Three | 63 | 14.6 |

| Four | 33 | 7.7 |

| Other / 5+ | 52 | 12.1 |

| Unknown | 3 | 0.7 |

| Educational Attainment | ||

| 8th grade or less | 44 | 10.2 |

| Some HS, but didn't graduate | 74 | 17.2 |

| HS grad or GED | 152 | 35.3 |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 115 | 26.7 |

| 4-year college graduate | 25 | 5.8 |

| Some graduate/professional | 21 | 4.9 |

| Household Annual Income | ||

| Less than $10,000 | 147 | 34.1 |

| 10,000 – 19,999 | 125 | 29.0 |

| 20,000 – 29,999 | 55 | 12.8 |

| 30,000 – 39,999 | 26 | 6.0 |

| 40,000 – 49,999 | 16 | 3.7 |

| 50,000 or more | 3 | 0.7 |

| Don't know or missing | 59 | 13.7 |

| Ever had public support for: | ||

| Housing | 142 | 35.1 |

| Food | 218 | 51.9 |

| Post High School Education | 96 | 24.2 |

| Job training | 102 | 25.8 |

| Finding a job | 97 | 24.9 |

| Daycare | 36 | 9.6 |

| Transportation | 122 | 30.5 |

| Income tax credit | 152 | 35.8 |

| General Health Status | ||

| Excellent | 51 | 11.9 |

| Very good | 103 | 24.0 |

| Good | 155 | 36.1 |

| Fair | 98 | 22.8 |

| Poor | 23 | 5.4 |

| Have the following illnesses | ||

| High blood pressure | 134 | 32.5 |

| Diabetes | 44 | 11.3 |

| Cancer | 15 | 4.0 |

Where the numbers add up to less than the total number of participants this reflects missing data.

DC Healthcare Alliance is a public-private partnership providing free health insurance to Washington DC residents who have no health insurance and have income at or below 200% of the federal poverty level, including those not eligible for Medicaid.

Assessment of deliberative process

The majority of participants strongly agreed that the exercise was informative (84%), they had a chance to present their views (91%), their views were considered by the rest of the group (86%), and they were treated with respect (92%). Even though 38% of participants reported that their group's selections differed considerably from their own, greater than 70% were still willing to abide by the package that the group had agreed upon (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participant Assessment of the Deliberative Process

| Strongly agree | Somewhat agree | Neutral | Somewhat disagree | Strongly disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The exercise was informative | 84 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| The group reached its decision fairly | 76 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| I had a chance to present my views | 91 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| My views were considered | 86 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| I was treated with respect | 92 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| My benefits plan was very different from the group | 38 | 30 | 11 | 8 | 13 |

| I am willing to accept the group's plan | 70 | 22 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

1. Numbers reflect percentage of participants in each category and are rounded to the nearest percent.

Comparison of attitudes before and after exercise regarding factors that affect health

Prior to the exercise, the percentage of participants who believed either somewhat or strongly that health depends on quality of insurance, lifestyle choices, income, or neighborhood were 58, 92, 51, and 27 percent respectively. After the exercise, a significantly higher percentage of participants strongly agreed that each of these factors influence health (p<0.01) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of Attitudes Before and After the REACH Exercise

| Strongly agree | Somewhat agree | Neutral | Somewhat disagree | Strongly disagree | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health depends on insurance quality | before | 34 | 24 | 13 | 9 | 20 | <0.0001 |

| after | 60 | 16 | 10 | 5 | 9 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Health depends on lifestyle choices | before | 19 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 0.0036 |

| after | 85 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Health depends on income | before | 26 | 25 | 11 | 12 | 26 | <0.0001 |

| after | 40 | 24 | 13 | 5 | 17 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Health depends on neighborhood | before | 11 | 16 | 17 | 11 | 46 | <0.0001 |

| after | 30 | 18 | 18 | 9 | 25 | ||

1. Numbers reflect percentage of participants in each category and are rounded to nearest percent

2. P-value based on a paired t-test with strongly disagree=1 and strongly agree=5

Reasons for Inclusion and Exclusion

Group priorities, as indicated by the percentage of groups choosing to include each of the 16 interventions, as well as the types of reasons for inclusion and exclusion given for each specific intervention are shown in Table 5. Select participant quotes that serve as examples to elucidate each type of reason for inclusion and exclusion can be found in Table 6. More extensive participant quotes from the qualitative analysis are available online at http://www.bioethics.nih.gov/research/chat.shtml.

Table 5.

Intervention Priorities and Reasons Given for Inclusion and Exclusion

| Intervention | Priority1 | Reasons for Inclusion | Reasons for Exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health Coverage | 100 | Basic necessity | Unnecessary |

| Immediate need | Potential for abuse | ||

| Benefits everyone | |||

| Link to health | |||

|

| |||

| Housing | 91 | Basic necessity | Unnecessary |

| Immediate need | Ineffective | ||

| Major expense | Not sufficient | ||

| Individual benefit | |||

| Community impact | |||

| Link to health | |||

|

| |||

| Dental Care | 80 | Basic necessity | Unnecessary |

| Immediate need | More pressing issues | ||

| Major expense | |||

| Link to health | |||

|

| |||

| Job Training | 75 | Immediate need | Unnecessary |

| Long term investment | Ineffective | ||

| Individual benefit | Not sufficient | ||

| Community impact | More pressing issues | ||

| Link to health | Alternatives | ||

|

| |||

| Adult Education | 70 | Basic necessity | Unnecessary |

| Immediate need | Not sufficient | ||

| Long term investment | More pressing issues | ||

| Individual benefit | |||

| Community impact | |||

|

| |||

| Counseling | 68 | Immediate need | Unnecessary |

| Individual benefit | More pressing issues | ||

| Community impact | |||

|

| |||

| Neighborhood Improvement | 68 | Basic necessity | Unnecessary |

| Immediate need | More pressing issues | ||

| Small cost | |||

| Benefits everyone | |||

| Link to health | |||

|

| |||

| Daycare | 66 | Immediate need | Unnecessary |

| Major expense | Not sufficient | ||

| Individual benefit | More pressing issues | ||

| Community impact | Does not benefit everyone | ||

| Alternatives | |||

|

| |||

| Childhood Education | 64 | Basic necessity | Not sufficient |

| Immediate need | |||

| Long term investment | |||

|

| |||

| School Meals | 59 | Immediate need | Does not benefit everyone |

| Individual benefit | |||

| Link to health | |||

|

| |||

| Job Placement | 57 | Immediate need | Unnecessary |

| Long term investment | Ineffective | ||

| Individual benefit | Not sufficient | ||

| Link to health | |||

|

| |||

| Healthy Behavior Incentives | 55 | Immediate need | Unnecessary |

| Small cost | More pressing issues | ||

| Long term investment | |||

| Individual benefit | |||

| Benefits everyone | |||

| Link to health | |||

|

| |||

| Food Stamps | 39 | Basic necessity | Unnecessary |

| Immediate need | Alternatives | ||

| Major expense | Potential for abuse | ||

|

| |||

| Grocery Store Incentives | 34 | Immediate need | Unnecessary |

| Small cost | More pressing issues | ||

| Community impact | |||

| Benefits everyone | |||

| Link to health | |||

|

| |||

| Transportation | 34 | Immediate need | Unnecessary |

| Major expense | Not sufficient | ||

| Community Impact | More pressing issues | ||

| Does not benefit everyone | |||

| Potential for abuse | |||

|

| |||

| English Education | 32 | Immediate need | Not sufficient |

| Community impact | More pressing issues | ||

| Does not benefit everyone | |||

Priority as indicated by the percentage of groups selecting this intervention

Table 6.

Reasons for Inclusion and Exclusion and Select Participant Quotes

| Reasons for Inclusion | Select Participant Quote |

|---|---|

| Basic necessity | “You need education no matter what.” |

| Immediate need | “I think housing help should be on there, but not just for the simple fact of homelessness. You have a lot of people who are in their homes now, struggling to maintain and try and keep their homes so that they do not become homeless.” |

| Major living expense | “Most people in Washington, DC have kids and the daycare facilities are very expensive.” |

| Individual benefit | “With good job training you would be able to do things better for yourself.” |

| Community impact | “The more people who take public transportation, the less highway expenses you need, the less traffic, the less pollution.” |

| Affects everyone | “Neighborhood is important to the growth of young people as well as to the peace of mind of older people.” |

| Costs little | “I think healthy behavior is a big plus. Plus, I'm getting a big bang for my buck. I'm only using one dot.” |

| Long term investment | “I believe that children are the future, so I know I want my kids to definitely have a good education.” |

| Link to Health | “Without health insurance it is very difficult to be healthy.” |

| Reasons for Exclusion | Select Participant Quote |

|---|---|

| Unnecessary | “Grocery stores are not something that we need because we already have many in the area.” |

| Ineffective | “For DC we do have the job placement centers out here but they send everyone on the same job interview.” |

| Insufficient | “English education is one part of what we need but that doesn't mean that because I speak English, I will get a job. There are thousands of people that speak English and don't have a job.” |

| Not beneficial to everyone | “I think that it would be a fund that would only help a specific group and not the community in general.” |

| Susceptible to abuse | “There's a lot of people that I have issued food stamps, they're not using it for the purpose of food stamps.” |

| More pressing issues | “I think there are more important, other issues to deal with other than healthy behavior.” |

| Alternative | “I think every employer should provide daycare. I don't think a city should have to pay for it out of their tax dollars.” |

Overall, health insurance, housing, dental care, and job training were the interventions selected by the greatest number of groups. Participants saw health problems as a universal part of living, health services as central to health, and proper treatment difficult to access without insurance. Attention to dental health was justified in light of a recent case of a young boy who died from a brain abscess that resulted from poor dental care. Participant priorities were also informed by their community's struggle for affordable housing which participants portrayed as being exacerbated by rising housing prices during urban gentrification; housing was considered crucial to feeling safe and secure.

Interventions tended to fall into disfavor when participants believed there were more pressing issues, alternative services that could accomplish the same goal, or when too small a part of the community would benefit from the investment. For a combination of these reasons, food stamps, grocery store incentives, transportation, and English education were selected for inclusion by less than 40% of groups. The discussion surrounding food stamps highlighted participants' hesitancy in supporting interventions that may foster economic dependency and the pride and sense of empowerment that results from being able to provide for one's family. Groups were able to find a middle ground between complete reliance on the government and individual responsibility by acknowledging the need for some assistance, but emphasizing the importance of supporting interventions that would give people the means to better themselves. This often led groups to prioritize employment interventions while services like grocery store incentives and transportation were assigned a lower priority.

Participants engaged in substantial discussion toward the end of the decision process when few markers were left and they were faced with deciding between interventions that fulfill immediate needs, such as health care and housing, and interventions that they viewed as representing long term investments, such as education and employment services. Groups often concluded that interventions that allowed them to invest in the future were invaluable, however, it was also necessary to include interim measures that make these investments more realistic given present realities.

Discussion

Methods of community engagement in priority setting are well established and regarded, however, its use to foster public understanding of the social determinants of health has not showed clearly promising results. The social determinants of health are complex phenomena, yet the low income urban residents who participated in this study gained appreciation of them and were able to effectively make reasoned programmatic choices to address them. Successful deliberation depends on participants being well informed and educated about the issues being discussed. It also necessitates a respectful atmosphere in which every participant has equal and adequate opportunity to speak and be heard so that all points of view are taken into account (Burkhalter, Gastil, & Kelshaw, 2002). The exercise described in this study aimed to fulfill these requirements.

Overall, participants reported a positive assessment of the deliberative process, and their changes in attitudes about the social determinants of health contrasts with the findings from previous research that opinions about the social determinants of health are not easily amenable to change during deliberation (Abelson et al 2003a). Our findings may also be contrasted with the findings of Luskin et al who found that during deliberative polling, the public in Manchester was likely to consider reduction in unemployment and poverty less important to reducing crime than they did prior to the deliberative process (Luskin et al., 2002). In addition, the finding that 70% of our participants were willing to accept their groups' package of benefits regardless of whether it matched their own individual choices demonstrates that the deliberation led to participant buy-in which has the potential to translate into greater legitimacy in policy decisions.

While this study was designed to encourage participants to understand the role of factors beyond traditional health care that influence personal and community health, health insurance and dental care emerged as two of the top three priorities chosen by 100% and 80% of groups, respectively. This finding provides evidence that participants continued to place great faith in traditional medical care even in the face of efforts to expand their understanding of the socio-economic determinants of health. This likely reflects the heightened interest in expanding health insurance in the U.S. given the historic percentage of the uninsured and efforts at health insurance reform that took place during the course of our study. Similarly, prominent attention to the importance of dental health by the Surgeon General and other policy experts (USDHHS; Mouradian, Wehr and Crall, 2000) in addition to the dramatic publicity of the death of a child due to a brain abscess caused by poor dental care (Otto, February 28, 2007), point out the extent to which publicity heightens the saliency of a particular factor that contributes to health (Center for Health and Healthcare in Schools).

Another notable finding is the extent to which participants began the exercise with a strong appreciation of the importance of personal health behavior. This is not surprising since there is substantial emphasis in the U.S. on health promotion and education of the public about healthy behavior. Additionally, the American media portrayal of health inequalities tends to emphasize personal behaviors rather than societal factors as the major determinants of health. The extent to which personal health choices are governed by the resources and opportunities available to an individual, and that available resources are in turn influenced by structural inequalities that are beyond an individual's control is rarely discussed (Niederdeppe, Bu, Borah, Kindig, & Robert, 2008).

Although participants placed continued emphasis on the importance of traditional medical care they clearly gained understanding of socio-economic factors that contribute to health during the course of the exercise. This finding may be particularly useful given the evidence suggesting that the American public is largely unaware of the importance that social and economic factors play in shaping an individual's health trajectory (Harvard School of Public Health/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/ICR, 2005; Robert et al., 2008; The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 1999). Broaching such issues with the public and educating them about the various determinants of health is critical to building the impetus necessary to address these inequalities and support practical solutions. The findings that 91% of groups included housing in their package of interventions and that 68% included neighborhood improvement, indicate that the exercise did stimulate awareness that such factors can affect health. The reasoning expressed by the groups that alluded to current realities they experienced in their city or neighborhood, suggests that the exercise may also serve as a needs assessment tool. These insights into the conditions and resources that need to be improved in the community are valuable given the growing recognition that any plan designed to ameliorate the social determinants of health will require a broad array of services that work synergistically. Understanding the specific needs of a community will help to determine what combination of services will prove to be most successful and in what settings.

With growing evidence detailing interventions and services that have been successful to address the numerous determinants of ill health, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recently issued guidance on how best to engage communities in these interventions based on a scoping review of the various methods that have been used in the UK (Popay, Attree, Hornby, Milton, Whitehead, French, et al., 2007). The study described in this paper adds to this body of work a prioritization exercise that is based on a well-validated decision tool. Given the exploratory nature of this study, we are cautious regarding the policy implications of these specific results since the generalizability is limited by the fact that the exercise was conducted with a small, non-random sample of the target population. There is also the possibility that participants may have made different decisions if the deliberations had been presented as likely to result in actual policy changes as opposed to being a hypothetical exercise. Another limitation of this paper might be raised by social epidemiologists who would criticize the project for offering individually based interventions rather than offering options that systematically address substantial structural social change aimed at reducing social inequality and health disparity, such as fair employment practices, gender equity, and political empowerment that have been recommended by the WHO Commission on the Social Determinants of Health (Venkatapuram, 2010). While some might argue that the latter approach would have been preferable, our intent here was to focus on interventions that require monetary resources and that were amenable to concrete policy interventions.

Despite these limitations, the exercise described in this study is useful as a deliberative approach to enhance dialogue between community residents and local governments in order to create partnerships, provide education, and empower community members. We would not expect public priorities to be translated directly into policy, but we do believe that they can serve as an important and necessary ingredient in the policy making process. This study was conducted in collaboration with the local health department, and it is unlikely that any attempt to engage disadvantaged communities will be successful without a receptive and responsive local government. In a climate of reduced budgets it seems reasonable that government officials will find the informed views of low-income individuals to be useful in planning and budgeting services to most effectively address the immediate needs of the community.

The methodology used in this exercise can be replicated on a broader scale and in different settings. The decision tool that this exercise was based on, Choosing Healthplans All Together, has been used for research, policy, and teaching purposes. It has been used in the form of a paper version, an electronic version, and an online version, and it has been used in several countries including the United States, New Zealand, and India (Danis, Ginsburg, & Goold, 2010a). The deliberative process described in this paper can also be applicable to a variety of settings by appropriately modifying the interventions and their costs to reflect local intricacies.

It should be acknowledged that the feasibility of conducting a deliberative process such as this one is limited by the constraints related to getting individuals in the same room in order to permit this type of unique interaction. The factors for gathering group participants in this study included using recruiters who were familiar to the community and providing financial compensation. Online deliberation serves as a promising method to overcome these challenges since it has been documented to be more convenient, more flexible, and less costly (Davies and Gangadharan, 2009). Fishkin has found that participants gained knowledge and changed their views during online polling about foreign policy issues in a manner similar to results from face-to-face deliberation (Fishkin, 2009). Gronlund, Strandberg, and Himmelroos have also reported promising results with virtual interaction with similar outcomes between face-to-face deliberation and online deliberation about energy politics (Gronlund, Strandberg, & Himmelroos, 2009). The Healthcare Dialogue project, which was focused on health care reform, is another example that suggests that an online discussion may allow for a more open exchange of dissenting opinions (Price, 2009). Yet fostering careful, thoughtful, and meaningful dialogue during online deliberation is likely to remain a challenge until virtual meeting is more technically feasible (Davies and Gangadharan 2009). Furthermore, whether online deliberation can be as effective with disadvantaged communities remains to be determined given the need to overcome inequalities in access. Combining research like this with the knowledge that can be gained about communities' priorities and lived experiences is valuable in the development of policy that is aimed at bettering that lived experience so that all people can live healthier, more productive lives.

Acknowledgments

The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies of the National Institutes of Health or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The authors do not have any affiliation with programs depicted in the exercise.

The study was funded by the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities and the Dept. of Bioethics at the National Institutes of Health. We thank our colleagues who collaborated in conducting the “Choosing Healthful Interventions Study”: Namrata Kotwani, Pamela Carter-Nolan, Ph,D, John Davies-Cole, Ph.D., and Ivonne Rivera, MPH. We also thank Joanne Garrett, Ph.D for assistance with the statistical analysis; Sara Hull, Ph.D, for guidance with the qualitative analysis and thoughtful review of the manuscript; and Bob Goodin, D.Phil for thoughtful review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abelson J, Eyles J, McLeod CB, Collins P, McMullan C, Forest PG. Does deliberation make a difference? Results from a citizens panel study of health goals priority setting. Health Policy. 2003a;66(1):95–106. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(03)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abelson J, Forest PG, Eyles J, Smith P, Martin E, Gauvin FP. Deliberations about deliberative methods: issues in the design and evaluation of public participation processes. Soc Sci Med. 2003b;57(2):239–251. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acheson D BD, Chambers J, Graham H, Marmot M, Whitehead M. The Report of the Independent Inquiry into Health Inequalities. the Stationary Office; London, England: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bratu I, Martens PJ, Leslie WD, Dik N, Chateau D, Katz A. Pediatric appendicitis rupture rate: disparities despite universal health care. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(11):1964–1969. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhalter S, Gastil J, Kelshaw T. A Conceptual Definition and Theoretical Model of Public Deliberation in Small Face-to-Face Groups. Communication Theory. 2002;4:398–422. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Health and Healthcare in Schools Pediatric Oral Health: New Attention to an Old Problem. available at http://www.healthinschools.org/News-Room/EJournals/Volume-8/Number-2/Pediatric-Oral-Health.aspx.

- Danis M, Biddle AK, Dorr Goold S. Insurance benefit preferences of the low-income uninsured. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(2):125–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis M, Ginsburg M, Goold S. Experience in the United States with public deliberation about health insurance benefits using the small group decision exercise, CHAT. J Ambul Care Manage. 2010a;33(3):205–214. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181e56340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis M, Kotwani N, Garrett J, Rivera I, Davies-Cole J, Carter-Nolan P. Priorities of low-income urban residents for interventions to address the socio-economic determinants of health. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010b;21(4):1318–1339. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danis M, Lovett F, Sabik L, Adikes K, Cheng G, Aomo T. Low-income employees' choices regarding employment benefits aimed at improving the socioeconomic determinants of health. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(9):1650–1657. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.091033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies T, Gangadharan SP, editors. Online Deliberation: Design, Research and Practice. CSLI Publications; San Francisco, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan P, Cookson R, Ferguson B. Effect of discussion and deliberation on the public's views of priority setting in health care: focus group study. BMJ. 1999;318(7188):916–919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7188.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishkin JS. The Voice of the People: Public Opinion and Democracy. Yale University Press; New Haven: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fishkin JS. Virtual Public Consultation:Prospects for Internet Deliberative Democracy. In: Davies T, Gangadharan SP, editors. Online Deliberation: Design, Research, and Practice. CSLI Publications; San Francisco, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gastil J, Levine P, editors. The deliberative democracy handbook: Strategies for effective civic engagement in the twenty-first century. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Goodin RE, Dryzek JS. Deliberative Impacts: The Macro-Political Uptake of Mini-Publics. Politics & Society. 2006;34(2):219–244. [Google Scholar]

- Goold SD, Biddle AK, Klipp G, Hall CN, Danis M. Choosing Healthplans All Together: a deliberative exercise for allocating limited health care resources. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2005;30(4):563–601. doi: 10.1215/03616878-30-4-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronlund K, Setala M, Herne K. Deliberation and civic virtue: lessons from a citizen deliberation experiment. European Political Science Review. 2010;2(1):95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Gronlund K, Strandberg K, Kimmelroos S. The challenge of deliberative democracy online- A comparison of face-to-face and virtual experiments in citizen deliberation. Information Polity. 2009;14(3):187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann A, Thompson D. Why Deliberative Democracy is Different. Social Philosophy and Policy. 2000;17(01):161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Harvard School of Public Health/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/ICR . A poll conducted by The Harvard School of Public Health, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and ICR/International Communications Research. 2005. Americans' Views of Disparities in Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- Heymann J. Healthier societies : from analysis to action. Oxford University Press; Oxford ; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- House JS. Relating social inequalities in health and income. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2001;26(3):523–532. doi: 10.1215/03616878-26-3-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N, Oliff P, Williams E. In: An Update on State Budget Cuts. In Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, editor. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I, Blakely TA. When economists and epidemiologists disagree. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2001;26(3):533–541. doi: 10.1215/03616878-26-3-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo KD, Pikhart H, Kopp MS, Bobak M, Pajak A, Malyutina S, et al. Job insecurity and health: A study of 16 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazere E. In: Nowhere To Go: As DC Housing Costs Rise, Residents Are Left With Fewer Affordable Housing Options. D. F. P. Institute, editor. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lenaghan J. Involving the public in rationing decisions. The experience of citizens juries. Health Policy. 1999;49(1–2):45–61. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(99)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luskin RC, Fishkin JS, Jowell R. Considered Opinions: Deliberative Polling in Britain. British Journal of Political Science. 2002;32(3):455–487. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. Epidemiology of socioeconomic status and health: are determinants within countries the same as between countries? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;896:16–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milliman Inc. Cost Analysis Report for Intervention Programs to Address Socio-Economic Determinants of Health. 2007 http://www.bioethics.nih.gov/research/chat/Milliman%20Analysis%20Cost%20R eport.pdf.

- Mitton C, Smith N, Peacock S, Evoy B, Abelson J. Public participation in health care priority setting: A scoping review. Health Policy. 2009;91(3):219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouradian WE, Wehr E, Crall JJ. Disparities in Children's Oral Health and Access to Dental Care. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2625–2631. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J, Bu QL, Borah P, Kindig DA, Robert SA. Message design strategies to raise public awareness of social determinants of health and population health disparities. Milbank Q. 2008;86(3):481–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto M. For Want of a Dentist. The Washington Post; Washington DC: Feb 28, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Popay J, Attree P, Hornby D, Milton B, Whitehead M, French B, et al. Community engagement to address the wider social determinants of health: a review of evidence on impact, experience and process. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; London: 2007. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=folder&o=34709. [Google Scholar]

- Price V. Citizens Deliberating Online: Theory and Some Evidence. In: Davies T, Gangadharan SP, editors. Online Deliberation: Design, Research, and Practice. CSLI Publications; San Francisco, CA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Robert SA, Booske BC, Rigby E, Rohan AM. Public views on determinants of health, interventions to improve health, and priorities for government. WMJ. 2008;107(3):124–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seguin L, Xu Q, Gauvin L, Zunzunegui MV, Potvin L, Frohlich KL. Understanding the dimensions of socioeconomic status that influence toddlers' health: unique impact of lack of money for basic needs in Quebec's birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(1):42–48. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.020438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman HK, Laraia BA, Kushel MB. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140(2):304–310. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeeding T. Poor People in Rich Nations: The United States in Comparative Perspective. The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2006;20(1):69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Hamer M, O'Donnell K, Venuraju S, Marmot MG, Lahiri A. Socioeconomic status and subclinical coronary disease in the Whitehall II epidemiological study. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation . Race, Ethnicity & Medical Care: A Survery of Public Perceptions and Experiences. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- The Standing Committee on Social Affairs Science and Technology . Final Report of Senate Subcommittee on Population Health. 2009. A Healthy, Productive Canada: A Determinants of Health Approach. [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services . Oral Health In America: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; Rockville, MD: 2000. http://silk.nih.gov/public/hck1ocv.@www.surgeon.fullrpt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatapuram S. Global Justice and the Social Determinants of Health. Ethics and International Affairs. 2010;24(2):119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Williams RA. Eliminating healthcare disparities in America : beyond the IOM report. Humana Press; Totowa, N.J.: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . In: Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization, editor. WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health; Geneva: WHO: 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]