Over the last four decades, most Arab countries have undergone considerable development and both undergraduate and postgraduate education have spread and improved. Moreover, the number of journals published in Arab countries has increased, which has provided an outlet for publishing research that is of local importance but is not of much interest to the scientific community at large and, thus, has a small chance of being accepted by well-established journals with a wide readership. However, as Arab countries are part of the developing world, their contribution to the biomedical research literature is modest (1).

Measuring research output, even just quantitatively, is a complex and often controversial topic. Research articles indexed in the major databases (e.g. PubMed and Web of Science) are obvious targets when counting research publications. But what about research published in local journals, and should counts of PhD theses be given some consideration as well? Should registered patents also be taken into account? As it was not our intention to undertake research work as such, these and other questions led us to seeking a bird's eye view not of research output but of visibility of the research to the scientific community. So we searched PubMed using the sensitive query described by Tadmouri and Bissar-Tadmouri (2), ‘all’ articles for ‘each’ year from ‘each’ Arab country for the period from 1 January 1988 to 31 December 2007, and then we analysed the data separately for the two decades (1988–1997 and 1998–2007).

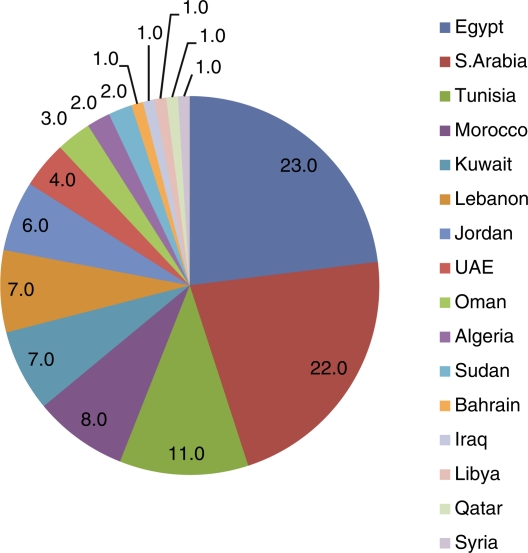

The number of publications from all Arab countries combined increased from 15,868 publications in the first decade to 35,211 publications in the second decade. But by itself this does mean much because of population growth. Moreover, the total number of publications in PubMed increased by about 50% between the two decades. However, we found that the contribution of Arab countries to the worldwide PubMed literature increased from .38–.6% between the two decades. Admittedly, the contribution is small, but nevertheless the progress is a positive development. The major contributors to Arab research during the second decade were clearly Saudi Arabia (one of the most affluent and the most populous in that group) and Egypt, followed by Tunisia. Together, these three countries accounted for 56% of the Arab output indexed in PubMed during the second decade (Fig. 1). We stress that these data are only absolute counts that have to be viewed with the differences in population size and economic resources in mind.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of contributions of Arab countries to publications from Arab countries indexed in PubMed during 1998–2007 listed in descending order.

Comparing countries according to their research policies was way beyond our intentions, but we took the economic factor into consideration by grouping the countries into three economic groups based on the per capita gross national product (World Bank, http://web.worldbank.org). Between the two decades, the number of PubMed-indexed publications per million population per year (which henceforth we will refer to as productivity) doubled in the lower-upper income group of countries (from 4 to 8) and tripled in the upper-middle group (from 11 to 30 publications per million population per year), which is in line with the crude notion that more money means more research. But in the upper-income group of countries it increased only slightly (from 32 to 38), which raises questions.

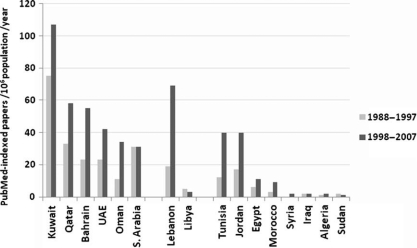

But grouping countries and making generalisations can lead to substantial errors because not all countries within each economic group perform at the same level. So to identify the countries most responsible for substantial progress or for its lack, we went on to analyse the countries individually. Analysis of the trend between the two decades in the number of PubMed-indexed publications per million population per year for each country shows some remarkable differences (Fig. 2). In the upper income group of countries, Kuwait clearly outperformed its peers while Saudi Arabia stagnated. Productivity remained unchanged in Saudi Arabia at 30.6 and 30.7 publications per million population per year between the two decades. It might be argued that this stagnation in Saudi Arabia was caused by the Gulf War, and this might be partly true. But Kuwait, which was directly involved in the war, increased its productivity between the two decades from 75 to 107 publications per million population per year. In the group of upper-middle income countries, which includes only Lebanon and Libya, Lebanon's improvement is impressive with productivity increasing more than threefold, while Libya did not show any progress. The international embargo that had been imposed on Libya could have been a contributing factor but it cannot explain the stagnation in full. We believe that one factor that has held back research in Libya is the pattern of frequent changes in academic and research institutions and their policies. Also, there seems to be a tradition of using local publications and congress presentations toward promotion at the expense of publication in international journals which reduces visibility. But this seems to have begun changing in some institutions by providing incentives linked to the impact factor in which papers are published.

Fig. 2.

The number of PubMed-indexed publications per million population per year from Arab countries during two decades. The nations are classified according to the gross national income per capita (data obtained from World Bank, http://web.worldbank.org): group on the left: >$11,456; group in the middle: $3,706–$11,455; group on the right: $936–$3,706.

The Saudi–Kuwait and Libya–Lebanon comparisons indicate that major changes in research policies are needed in some Arab nations to boost their research output. These observed discrepancies could be due to resource allocation or to other aspects of research policies, or to both, and serious efforts should be made to identify the causes.

It is interesting that the top Arab countries in terms of the number publications per million population per year in the second decade included one high income country (Kuwait), one upper-middle country (Lebanon), and two lower-middle countries (Tunisia and Jordan) (Fig. 2). This goes to show that it is not the strength of the economy itself that is important in this respect but resource allocation and utilisation. One also wonders whether these countries are making better use of collaborative studies, particularly with nations in the developed world.

It seems that some of the Arab countries have been conducting their research activities substantially more efficiently and more effectively than most other Arab countries. How these countries have been running their research might not be modular compared to developed nations, but other Arab countries might be well served by benefiting from their experience. Indeed, trying to model the most effective systems in advanced nations does not always yield the same results, and gaining from the experience of countries that have a similar socio-economic profile might be more effective.

In conclusion, the remarkable differences between Arab nations in the international visibility of their research require exploration of the causes. Arab countries with poor performance can benefit from the experience of other Arab as well as non-Arab developing nations that have been showing better performance. Establishment of sound and stable policies for research, sufficient allocation of resources and their efficient utilisation, and integration of research in the academic and economic life of the nation are important matters for many Arab nations to consider.

References

- 1.Benamer HTS, Bakoush O. Arab nations lagging behind other Middle Eastern countries in biomedical research: a comparative study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tadmouri GO, Bissar-Tadmouri N. A major pitfall in the search strategy on PubMed. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]