Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP) is increasingly performed for lesions of the body and tail of the pancreas. The aim of this study was to investigate short-term outcomes after LDP compared to open distal pancreatectomy (ODP) at a single, high-volume institution.

Methods

We reviewed records of patients who underwent distal pancreatectomy (DP) and compared perioperative data between LDP and ODP. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t- or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Categorical variables were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact test.

Results

A total of 360 patients underwent DP. Beginning in 2001, 95 were attempted and 71 completed laparoscopically with a 25.3% conversion rate. Compared to ODP, LDP had similar rates of splenic preservation, pancreatic fistula, and mortality. LDP had lower blood loss (150 vs. 900 mL, p<0.01), smaller tumor size (2.5 vs. 3.6 cm, p<0.01), and shorter length of resected pancreas (7.7 vs. 10.0 cm, p<0.01). LDP had fewer complications (28.2% vs. 43.8%, p=0.02) as well as shorter hospital stays (5 vs. 6 days, p<0.01).

Conclusions

LDP can be performed safely and effectively in patients with benign or low-grade malignant neoplasms of the distal pancreas. When feasible in selected patients, LDP offers fewer complications and shorter hospital stays.

Keywords: Distal pancreatectomy, laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy, open distal pancreatectomy

Introduction

The laparoscopic approach continues to gain acceptance as an option for the surgical management of diseases of the distal pancreas. After initial reports in the mid-1990s, [1,2,3,4] several small series began to emerge in the literature documenting the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy (LDP). [5,6,7,8,9] Although prospective, randomized trials are lacking, a growing number of single- and multi-institution case series affirm the benefits of LDP versus open distal pancreatectomy (ODP). [10,11,12,13] We herein report a large, single-institution series of distal pancreatectomy (DP) and compare differences in clinical outcomes between the laparoscopic and open approaches.

Materials and Methods

We performed a retrospective review of a prospectively maintained database of patients with pancreatic disease. The database is maintained by The Pancreas Center of Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) and includes the patients of four surgeons (J.A., J.C., J.L., B.S.). After approval from the institutional review board (IRB) and in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations, we queried our database to identify all patients who underwent DP at CUMC from 1991 through 2009.

For the purposes of comparing LDP to ODP, we used inclusion and exclusion criteria to define each group as follows. We included only those patients who underwent LDP or ODP during the same time period, beginning with the first attempted LDP in 2001. For the LDP group, we excluded patients who underwent laparoscopic-assisted DP, which was defined as the preoperative plan to perform only part of the operation laparoscopically prior to laparotomy. For the ODP group, we excluded patients who underwent DP as part of a completion pancreatectomy as well as those who underwent concomitant portomesenteric venous resection and reconstruction. We also excluded patients who underwent DP secondary to debridement for necrotizing pancreatitis, oncologic resection for non-pancreatic primary neoplasms invading the pancreas, and pancreatic injury during another operation. We included the laparoscopic-converted-to-open procedures in the ODP group for all statistical analyses except for the subsets in which the LDP, ODP, and converted groups were examined independently.

Descriptive data were collected by review of patients’ medical records. Preoperative variables included age, gender, race, and significant comorbidity, defined as the presence of coronary artery disease (CAD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), or chronic kidney disease (CKD). Intraoperative variables were obtained from nurse, anesthesiologist, and surgeon reports. Operating room (OR) time was defined as the time between patient entry into and exit from the OR. Anesthesia time was defined as the time between start of anesthesia care in the OR and patient exit from the OR. Incision time was defined as the time between incision start and incision close. Pathologic diagnosis, greatest lesion diameter, length of resected pancreas, margin status, and regional lymph node status were determined from final pathology reports. Perioperative complications were gathered from daily progress notes and discharge summaries and graded using the system proposed by DeOliveira and colleagues. [14] Overall morbidity was defined as any complication, and major morbidity was defined as complications grade III and greater. Pancreatic fistula was assessed and graded according to the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula recommendations. [15] Length of stay (LOS) was calculated from date of operation to date of hospital discharge. Readmission rate was defined as readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge. Perioperative mortality was defined as death within 30 days of the operation or within the same hospital admission as the operation.

All operations were performed by four pancreatic surgeons (J.A., J.C., J.L., B.S.) using our institution’s standardized technique. For the laparoscopic cases, a 4-port technique was used with 5, 10, and 12 mm trocars in varying combinations at the surgeon’s discretion. One of the trocar incisions was extended to remove the specimen intact. For the open cases, a single incision was used, either upper vertical midline or left subcostal depending on patient body habitus and individual surgeon preference. Conduct of the operation, including lesion identification with ultrasound, splenic mobilization (if applicable), and pancreatic exposure and mobilization, were similar for both the laparoscopic and open approaches. For spleen-preserving DPs, an attempt to spare the splenic artery and vein was made in all patients. A variety of techniques were used to control the pancreas stump based on individual surgeon preference. Examples of these techniques included sutures, staples, sutures and staples combined, or staples with bioabsorbable staple-line reinforcement. Operative drains were placed at the surgeon’s discretion.

Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were reported as number and percentage (%). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using the R statistical software program (version 2.8).

Results

From March 11, 1991 through December 31, 2009, a total of 387 DPs were attempted, with 360 (93%) completed and 27 (7%) aborted. Fifty-nine (16.4%) of the completed DPs were performed prior to use of the laparoscopic approach in 2001 and were excluded from further analysis. Eight open completion pancreatectomies, 6 open DPs with concomitant portomesenteric venous resections, and 4 laparoscopic-assisted DP cases were excluded. Ten DPs performed during debridement for necrotizing pancreatitis, 7 performed during oncologic resection for non-pancreatic primary neoplasms, and 3 performed secondary to pancreatic injury during other operations also were excluded. Of the remaining 263 DPs, 168 (63.9%) were open, 71 (27%) were laparoscopic, and 24 (9.1%) were laparoscopic-converted-to-open, with a laparoscopic-to-open conversion rate of 25.3%.

Patient characteristics

There were no statistically significant differences in demographics and preoperative comorbidities between the LDP and ODP groups. The mean age was 58.2 ± 14.1 years in the LDP group and 60.2 ± 15.2 years in the ODP group (p=0.36). There were 49 (69%) women and 22 (31%) men in the LDP group and 119 (62%) women and 73 (38%) men in the ODP group, with the majority being Caucasian in both groups. The incidences of CAD, COPD, DM, and CKD were similar between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and preoperative comorbidities for patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy

| Variable | LDP (n=71) | ODP (n=192) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, year, mean (SD*) | 58.2 (14.1) | 60.2 (15.2) | 0.36 |

| Gender, M/F | 22/49 | 73/119 | 0.29 |

| Race (%)a | |||

| Caucasian | 57 (80.3) | 139 (72.4) | 0.19 |

| Black | 5 (7.1) | 6 (3.1) | |

| Asian | 1 (1.4) | 5 (2.6) | |

| Hispanic | 4 (5.6) | 23 (12.0) | |

| Other | 4 (5.6) | 19 (9.9) | |

| Comorbidities (%)b | |||

| CAD | 6 (8.5) | 18 (9.4) | 1.00 |

| COPD | 4 (5.6) | 12 (6.3) | 1.00 |

| DM | 13 (18.3) | 35 (18.2) | 1.00 |

| CKD | 1 (1.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0.47 |

Standard deviation (SD)

Statistical analysis was performed on Caucasian versus all other races.

Coronary artery disease (CAD), Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Diabetes mellitus (DM), Chronic kidney disease (CKD). Some patients had more than one comorbidity.

Intraoperative characteristics

Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) was used to identify lesions in 37 (52.1%) LDP cases and 83 (43.2%) ODP cases (p=0.20). Various methods were employed to control the distal pancreatic remnant in both groups. Stapler and bio-sealant was used most commonly in the LDP group (77.5%) whereas suture (44.8%) and stapler with bio-sealant (39.1%) were most common in the ODP group. The rates of splenic preservation were similar in both groups (15.5% vs. 15.6%, p=0.93). Patients had lower median blood loss in the LDP group (150 mL, IQR 100–250 mL) compared to the ODP group (900 mL, IQR 400–1400 mL; p<0.01). Operative drains were placed with comparable frequency in both groups (56.3% vs. 67.2%, p=0.10). Median OR time (250 min, IQR 225–285 min2 vs. 270 min, IQR 235–345 min; p<0.01) and median anesthesia time (229 min, IQR 205–259 min vs. 237 min, IQR 205–314 min; p<0.01) were shorter in the LDP group compared to the ODP group. There was no statistically significant difference in median incision times between the groups (191 min, IQR 163–214 min vs. 195 min, range 166–263 min; p=0.35) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Intraoperative characteristics for patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy

| Variable | LDP (n=71) | ODP (n=192) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating room time, minutes | |||

| Median (IQR*) | 250 (225–285) | 270 (235–345) | <0.01 |

| Anesthesia time, minutes | |||

| Median (IQR) | 229 (205–259) | 237 (205–314) | <0.01 |

| Incision time, minutes | |||

| Median (IQR) | 191 (163–214) | 195 (166–263) | 0.35 |

| Intraoperative blood loss, mL | |||

| Median (IQR) | 150 (100–250) | 900 (400–1400) | <0.01 |

| Splenic preservation (%) | 11 (15.5) | 30 (15.6) | 0.93 |

| Prior splenectomy | 0 (0) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Intraoperative ultrasound (%) | 37 (52.1) | 83 (43.2) | 0.20 |

| Intraoperative drain (%) | 40 (56.3) | 129 (67.2) | 0.10 |

| Distal pancreas control | |||

| Suture | 1 | 86 | |

| Staple | 15 | 7 | |

| Suture and staple | 0 | 12 | |

| Suture and bio-sealant | 0 | 2 | |

| Staple and bio-sealant | 55 | 75 | |

| Suture, staple, and bio-sealant | 0 | 6 | |

| Pancreaticojejunostomy | 0 | 3 | |

| Cystgastrostomy | 0 | 1 | |

Interquartile range (IQR)

Postoperative outcomes

Patients in the LDP group had fewer overall complications (28.2% vs. 43.8%, p=0.02) and fewer major complications (8.5% vs. 18.8%, p=0.04) than those in the ODP group. There were no statistically significant differences in overall pancreatic fistula rate (11.3% vs. 14.1%, p=0.55) and clinically significant pancreatic rate (7% vs. 12.5%, p=0.27) between the LDP and ODP groups. There were no statistically significant differences in rates of reoperation (5.6% vs. 3.6%, p=0.50) and readmission (4.2% vs. 8.9%, p=0.30) between the groups. Patients in the LDP group had shorter median LOS compared to those in the ODP group (5 days, IQR 4–6 days vs. 6 days, IQR 5–8 days; p<0.01). Nineteen (26.8%) patients versus 118 (61.5%) patients had median LOS longer than 5 days (p<0.01). The mortality rate was nil in the LDP group versus 1% in the ODP group (p=1.00) (Table 3). In a subset analysis of spleen-preserving DP versus en bloc DP with splenectomy, there were no statistically significant differences in morbidity, pancreatic fistula, LOS, and mortality (Table 4).

Table 3.

Postoperative outcomes for patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy

| Variable | LDP (n=71) | ODP (n=192) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall morbidity (%) | 20 (28.2) | 84 (43.8) | 0.02 |

| Major morbidity (%) | 6 (8.5) | 36 (18.8) | 0.04 |

| Pancreatic fistula (%) | 8 (11.3) | 27 (14.1) | 0.55 |

| Grade A | 3 | 3 | |

| Grade B | 2 | 6 | |

| Grade C | 3 | 18 | |

| Reoperation (%) | 4 (5.6) | 7 (3.6) | 0.50 |

| Readmission (%) | 3 (4.2) | 17 (8.9) | 0.30 |

| Mortality (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.0) | 1.00 |

| Length of stay, days | |||

| Median (IQR*) | 5 (4–6) | 6 (5–8) | <0.01 |

| Length of stay greater than 5 days (%) | 19 (26.8) | 118 (61.5) | <0.01 |

Interquartile range (IQR)

Table 4.

Postoperative outcomes for patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy: Splenic preservation versus splenectomy

| Variable | Splenic Preservation (n=41) | Splenectomy (n=218) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall morbidity (%) | 18 (43.9) | 85 (39.0) | 0.56 |

| Major morbidity (%) | 6 (14.6) | 36 (16.5) | 0.76 |

| Pancreatic fistula (%) | 6 (14.6) | 29 (13.3) | 0.82 |

| Reoperation (%) | 2 (4.9) | 9 (4.1) | 0.69 |

| Readmission (%) | 2 (4.9) | 18 (8.3) | 0.75 |

| Mortality (%) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0.29 |

| Length of stay, days | |||

| Median (IQR*) | 5 (4–7) | 6 (5–8) | 0.13 |

Interquartile range (IQR)

Final pathology

Sixty-two (87.3%) patients had benign pathology in the LDP group versus 118 (61.5%) in the ODP group (p<0.01). Nine (12.7%) patients had malignant pathology in the LDP group versus 74 (38.5%) in the ODP group (p<0.01). The laparoscopic approach was less likely to be used for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (4.2% vs. 30.2%, p<0.01). Patients in the LDP group had shorter average length of pancreas resected (7.7 ± 3.2 cm vs. 10.0 ± 3.6 cm, p<0.01) for smaller median tumor size (2.5 cm, IQR 1.5–4.0 cm vs. 3.6 cm, IQR 2.0–6.0 cm; p<0.01) than patients in the ODP group. The median number of lymph nodes (LN) resected were similar between both groups (6, IQR 2.5–12.0 vs. 8, IQR 3.0–13.0; p=0.29). The number of patients with positive LN was 6 (8.5%) in the LDP group versus 36 (18.8%) in the ODP group (p=0.04). Two (2.8%) patients had positive margins in the LDP group versus 25 (13%) patients in the ODP group (p=0.01). Of the 2 patients with positive margins in the LDP group, 1 had a low-grade nonfunctional pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm and 1 had pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma on final pathology (Table 5).

Table 5.

Pathology characteristics for patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy

| Variable | LDP (n=71) | ODP (n=192) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benign (%) | 62 (87.3) | 118 (61.5) | <0.01 |

| Mucinous cystic neoplasm | 17 | 26 | |

| Serous cystadenoma | 8 | 17 | |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 7 | 24 | |

| Pancreatitis | 1 | 9 | |

| Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm | 0 | 7 | |

| Pseudocyst | 1 | 9 | |

| Simple cyst | 3 | 1 | |

| Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor | 20 | 22 | |

| Other | 5 | 3 | |

| Castleman Disease | 0 | 1 | |

| Vascular malformation | 0 | 1 | |

| Islet cell hyperplasia | 0 | 1 | |

| Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia | 1 | 0 | |

| Acinar cell nodule | 1 | 0 | |

| Calcified vessels | 1 | 0 | |

| Heterotopic ossification | 1 | 0 | |

| Schwannoma | 1 | 0 | |

| Malignant (%) | 9 (12.7) | 74 (38.5) | <0.01 |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 3 | 58 | <0.01 |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma | 0 | 2 | |

| Pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma | 5 | 9 | |

| Other | 1 | 5 | |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 0 | 5 | |

| Leiomyosarcoma | 1 | 0 | |

| Lesion size, cm | |||

| Median (IQR*) | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | 3.6 (2.0–6.0) | <0.01 |

| Length of resected pancreas, cm | |||

| Mean (SD†) | 7.7 (3.2) | 10.0 (3.6) | <0.01 |

| Positive margin (%) | 2 (2.8) | 25 (13.0) | 0.01 |

| Number of lymph nodes evaluated | |||

| Median (IQR) | 6.0 (2.5–12.0) | 8.0 (3.0–13.0) | 0.29 |

| Patients with positive lymph nodes (%) | 6 (8.5) | 36 (18.8) | 0.04 |

Interquartile range (IQR)

Standard deviation (SD)

Laparoscopic to open conversion

Reasons for conversion included 9 (37.5%) bleeding, 7 (29.1%) adherent tumor, 4 (16.6%) difficult anatomy, 1 (4.2%) abdominal adhesions, 1 (4.2%) difficult localization of tumor, 1 (4.2%) enterotomy, and 1 (4.2%) large tumor. Of the converted cases, 7 (29.2%) had malignant pathology (6 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and 1 intraductal papillary mucinous carcinoma) and 17 (70.8%) had benign pathology on final histological examination. When the converted cases were compared separately to the LDP group, the converted cases had significantly larger intraoperative blood loss and longer median OR, anesthesia, and incision times (Table 6). When compared separately to the patients who had open DP, the converted cases had significantly longer median OR, anesthesia, and incision times, but were statistically similar with regard to pathology and postoperative outcomes (Table 7).

Table 6.

Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy versus laparoscopic converted to open distal pancreatectomy

| Variable | LDP (n=71) | Converted (n=24) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative characteristics | |||

| Operating room time, minutes | |||

| Median (IQR*) | 250 (225–285) | 343 (315–400) | <0.01 |

| Anesthesia time, minutes | |||

| Median (IQR) | 229 (205–259) | 325 (295–365) | <0.01 |

| Incision time, minutes | |||

| Median (IQR) | 191 (163–214) | 275 (237–329) | <0.01 |

| Intraoperative blood loss, mL | |||

| Median (IQR) | 150 (100–250) | 1000 (650–1500) | <0.01 |

| Splenic preservation (%) | 11 (15.5) | 4 (16.7) | 1.00 |

| Prior splenectomy | 0 (0) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Pathology | |||

| Benign (%) | 62 (87.3) | 18 (75.0) | |

| Malignant (%) | 9 (12.7) | 6 (25.0) | |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 3 | 6 | <0.01 |

| Other | 6 | 0 | |

| Lesion size, cm | |||

| Median (IQR) | 2.5 (1.5–4.0) | 4.0 (2.4–5.9) | 0.01 |

| Length of resected pancreas, cm | |||

| Mean (SD†) | 7.7 (3.2) | 11.2 (4.0) | <0.01 |

| Postoperative outcomes | |||

| Overall morbidity (%) | 20 (28.2) | 13 (54.2) | 0.03 |

| Major morbidity (%) | 6 (8.5) | 4 (16.7) | 0.27 |

| Pancreatic fistula (%) | 8 (11.3) | 2 (8.3) | 1.00 |

| Reoperation (%) | 4 (5.6) | 2 (8.3) | 0.64 |

| Readmission (%) | 3 (4.2) | 1 (4.2) | 1.00 |

| Mortality (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.2) | 0.25 |

| Length of stay, days | |||

| Median (IQR) | 5 (4–6) | 6 (4.5–8.5) | 0.01 |

Interquartile range (IQR)

Standard deviation (SD)

Table 7.

Open distal pancreatectomy versus laparoscopic converted to open distal pancreatectomy

| Variable | Open (n=168) | Converted (n=24) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative characteristics | |||

| Operating room time, minutes | |||

| Median (IQR*) | 265 (233–321) | 343 (315–400) | 0.02 |

| Anesthesia time, minutes | |||

| Median (IQR) | 228 (199–285) | 325 (295–365) | <0.01 |

| Incision time, minutes | |||

| Median (IQR) | 192 (157–236) | 275 (237–329) | <0.01 |

| Intraoperative blood loss, mL | |||

| Median (IQR) | 800 (400–1400) | 1000 (650–1500) | 0.09 |

| Splenic preservation (%) | 26 (15.5) | 4 (16.7) | 0.77 |

| Prior splenectomy (%) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Pathology | |||

| Benign (%) | 100 (59.5) | 18 (75.0) | |

| Malignant (%) | 68 (40.5) | 6 (25.0) | |

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 52 | 6 | 0.30 |

| Other | 16 | 0 | |

| Lesion size, cm | |||

| Median (IQR) | 3.5 (2.0–6.0) | 4.0 (2.4–5.9) | 0.74 |

| Length of resected pancreas, cm | |||

| Mean (SD†) | 9.8 (3.6) | 11.2 (4.0) | 0.12 |

| Postoperative outcomes | |||

| Overall morbidity (%) | 71 (42.3) | 13 (54.2) | 0.27 |

| Major morbidity (%) | 32 (19.0) | 4 (16.7) | 1.00 |

| Pancreatic fistula (%) | 25 (14.9) | 2 (8.3) | 0.54 |

| Reoperation (%) | 5 (3.0) | 2 (8.3) | 0.21 |

| Readmission (%) | 16 (9.5) | 1 (4.2) | 0.70 |

| Mortality (%) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (4.2) | 0.23 |

| Length of stay, days | |||

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5–8) | 6 (4.5–8.5) | 0.66 |

Interquartile range (IQR)

Standard deviation (SD)

Discussion

The laparoscopic approach is being used with increasing frequency for the surgical management of pancreatic disease, particularly benign or low-grade disease of the distal body and tail. Laparoscopic distal pancreatic resection was first reported by Cuschieri in 1994 [1] and later described by Gagner in 1996. [4] Since then, a growing body of case reports and single- and multi-institution series suggest that LDP can be performed with morbidity and mortality rates comparable to those of ODP and with the added benefit of shorter hospital stays. [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,16]

Eom and colleagues [17] used a case-control design with 2:1 matching to compare 62 patients who underwent ODP with 31 patients who underwent LDP. The authors demonstrated similar morbidity and shorter hospital stays in the LDP group compared to the ODP group (11.5 vs. 13.5 days, p=0.049). Likewise, Nakamura and colleagues [18] compared the outcomes of 21 patients who underwent LDP with 16 patients who underwent ODP and found no difference in morbidity and shorter hospital stays in the LDP group (10.0 vs. 25.8 days, p<0.0001).

The largest single-institution series we encountered was by Kim and colleagues [19] who compared 93 LDP cases to 35 ODP cases, all performed by a single surgeon. Morbidity, mortality, and pancreatic fistula rates were similar in both groups, but the LDP group had shorter time to start of oral intake (2.8 days vs. 4.5 days; p<0.001) and shorter hospital stays (10 days vs. 16 days; p<0.01). The largest multi-institution series we encountered was by Kooby and colleagues [20] who compared 159 LDP patients to 508 ODP patients using data from eight different institutions. The authors reported no differences in operative times or pancreatic fistula rates between the LDP and ODP groups, but reported less blood loss (357 mL vs. 588 mL, p<0.01), fewer complications (40% vs. 57%, p<0.01), and shorter hospital stays (5.9 days vs. 9.0 days, p<0.01). Other large series in the literature demonstrate similar LDP outcomes, but without comparison to the open approach. [10,21,22]

Our study is a large, single-institution retrospective series that evaluates the laparoscopic and open approaches to DP performed during the same time period. We excluded several cases from the ODP group based on procedure-specific characteristics and oncologic principles for a more accurate comparison to LDP. A patient who has an open distal pancreatic resection as part of a debridement for necrotizing pancreatitis, for example, should not be compared to a patient who has a LDP for an isolated lesion. Likewise, a patient who has an open distal pancreatic resection for an invasive adrenal cortical carcinoma should not be included. We included the laparoscopic-converted-to open patients in the ODP group because they more closely resemble the open cases with regard to every variable except operative time. After inclusion and exclusion, the LDP and ODP groups were statistically similar with regard to demographics and preoperative comorbidities, further validating the comparison.

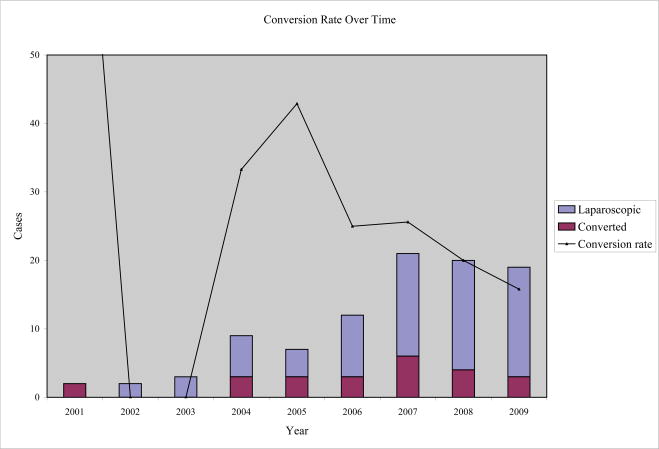

Our laparoscopic-to-open conversion rate of 25.3% is higher than those in the literature. Kooby and colleagues [20] reported a 13% conversion rate, and a recent meta-analysis by Borja-Cacho and colleagues [13] cited a 9.2% conversion rate. At our institution, we are relatively aggressive with use of the laparoscopic approach to distal pancreatic disease because of measurable patient benefit. Although the conversion prolongs operative times, it does not affect LOS or morbidity, mortality, and pancreatic fistula rates when compared to traditional ODP. We continue to refine our preoperative selection criteria to maximize success with the laparoscopic approach, and our rate of conversion has steadily declined in recent years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A graph of conversion rate over time shows a recent decline in laparoscopic to open distal pancreatectomy conversions.

Our rates of splenic preservation with both LDP (15.5%) and ODP (15.6%) are lower than those in the literature. Recent series in the literature report rates of splenic preservation that range from 31% to as high as 85% in select cases of benign and low-grade neoplasms using the laparoscopic approach. [23] Conventional DP includes splenectomy and is the procedure of choice to achieve adequate oncologic margins in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma of the body or tail. [24] However, the hypothesis that alterations in the hematologic and immune systems after splenectomy give rise to increased postoperative complications has prompted a shift toward spleen-preserving DP in patients with benign or low-grade malignant disease. [25,26]

The role of splenic preservation remains controversial. Shoup and colleagues [27] from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center noted that perioperative infectious complications (28% vs. 9%, p=0.01) and other severe complications (11% vs. 2%, p=0.05) were significantly higher with splenectomy compared to splenic preservation. They concluded that spleen-preserving DP can be performed safely with decreased perioperative morbidity. Other authors, however, report little or no benefit to splenic preservation, noting that it is more difficult, takes more time, and increases blood loss. [2,29] Benoist and colleagues [30] reported that DP with splenic preservation was associated with increased morbidity when compared to DP with splenectomy. Similarly, in a review of 49 laparoscopic pancreatic resections, Fernández-Cruz and colleagues [31] noted significantly higher morbidity after laparoscopic DP with splenic preservation compared to laparoscopic DP with splenectomy. Our data suggest no difference in clinical outcomes between spleen-preserving DP and DP with splenectomy with regard to morbidity, pancreatic fistula, and length of stay. Our bias is to perform DP with selective spleen preservation when oncologically appropriate.

The LDP patients had fewer overall complications than the ODP patients, but there was no difference in major complication, reoperation, readmission, and mortality rates. As in the literature, our data showed no difference in pancreatic fistula rates between the LDP and ODP groups (11.3% vs. 14.1%, p=0.68). In a case-control comparison of 15 laparoscopic and 15 open patients, for example, Velanovich [11] reported a pancreatic fistula rate of 13% in both groups. Kooby and colleagues [20] reported pancreatic fistula rates of 26% in 142 patients undergoing LDP and 32% in 200 patients undergoing ODP. Corcione and colleagues [12] reported an overall pancreatic fistula rate of 10.4% in their series of 19 patients undergoing LDP.

The laparoscopic approach has been shown to yield more rapid recovery and shorter hospitalizations in the treatment of several surgical diseases including colon cancer, cholecystitis, and appendicitis. [9,12] Our data echo the recent literature and suggest the same is true for select pancreatic disease. [16,18,32] When compared to ODP, the LDP group had statistically significant shorter hospital stays with markedly fewer patients staying longer than 5 days.

Our study’s main limitation is its retrospective nature. Cases more amenable to the laparoscopic approach were specifically selected, and without randomization our data reflect an inherent selection bias. Likewise, known cases of adenocarcinoma and suspected complex cases were routinely performed via laparotomy. Studies have shown that adenocarcinoma of the tail of the pancreas has a lower resectability rate than that of the head of the pancreas, likely secondary to patient presentation at a more advanced stage of disease. [11] Local fibrosis and inflammation incited by the tumor make mobilization difficult, and the laparoscopic approach may not allow sufficient regional dissection to perform an oncologically sound operation. [33,34] Distal pancreatic lesions thus need to be carefully evaluated preoperatively and selected for the laparoscopic approach. Postoperative pathologic examination has revealed successful laparoscopic removal of distal pancreatic adenocarcinoma in several reports, and recent studies suggest LDP for select cases of adenocarcinoma is acceptable provided that surgical margins are not compromised. [35]

Conclusion

Our experience affirms that LDP is a safe and effective option for select cases of distal pancreatic disease. When compared to ODP, successful LDP offers fewer complications and shorter hospital stays. Laparoscopic cases that are converted to open procedures have longer operative times, but clinical outcomes are comparable to conventional DP, supporting an aggressive but judicious use of the laparoscopic approach to DP. Additional research will better determine the role of splenic preservation during DP and clarify the best technique for minimizing pancreatic fistulae from the pancreatic remnant. Finally, further analysis is needed to determine the feasibility, safety, and efficacy of laparoscopic resection of adenocarcinoma of the distal pancreas.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32 HL 007854 14), Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, I.W. Foundation

This work was generously supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, an institutional Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award, and the I.W. Foundation.

Footnotes

Note: This manuscript was presented at the SSAT Annual Meeting in New Orleans, May 2010.

References

- 1.Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic surgery of the pancreas. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1994;39:178–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soper NJ, Brunt LM, Dunnegan DL, Meininger TA. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy in the porcine model. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:57–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02909495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:408–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00642443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gagner M, Pomp A, Herrera MF. Early experience with laparoscopic resections of islet cell tumors. Surgery. 1996;120:1051–1054. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(96)80054-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson EJ, Gagner M, Salky B, Inabnet WB, Brower S, Edye M, Gurland B, Reiner M, Pertsemlides D. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: single-institution experience of 19 patients. JAMA. 2001;193(3):281–287. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernández-Cruz L, Saenz A, Austudillo E, Martinez I, Hoyos S, Pantoja JP, Navarro S. Outcome of laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: endocrine and nonendocrine tumours. World J Surg. 2002;26:1057–1065. doi: 10.1007/s00268-002-6673-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shimuzu S, Tanaka M, Konomi H, Mizumoto K, Yamaguchi K. Laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: current indications and surgical results. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:402–406. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8164-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwin B, Mala T, Mathisen O, Gladhaug I, Buanes T, Lunde OC, Soreide O, Bergan A, Fosse E. Laparoscopic resection of the pancreas: a feasibility study of the short-term outcome. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:407–411. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9007-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dulucq JL, Wintringer P, Stabilini C, Feryn T, Perissat J, Mahajna A. Are major laparoscopic pancreatic resections worthwhile? A prospective study of 32 patients in a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1028–1034. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-2182-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mabrut JY, Fernández-Cruz L, Azagra JS, Bassi C, Delvaux G, Weerts J, Fabre JM, Boulez J, Baulieux J, Peix JL, Gigot JF. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: Results of a multicenter European study of 127 patients. Surgery. 2005;137:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Velanovich V. Case-control comparison of laparoscopic versus open distal pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(1):95–98. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corcione F, Marzano E, Cuccurullo D, Caracino V, Pirozzi F, Settembre A. Distal pancreas surgery: outcome for 19 cases managed with a laparoscopic approach. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1729–1732. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0839-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borja-Cacho D, Al-Refaie WB, Vickers SM, Tuttle TM, Jensen EH. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:758–765. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeOliveira ML, Winter JM, Schafer M, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Clavien PA. Assessment of complications after pancreatic surgery: a novel grading system applied to 633 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg. 2006;244:931–939. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000246856.03918.9a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palanivelu C, Shetty R, Jani K, Sendhilkumar K, Rajan PS, Maheshkumar GS. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: results of a prospective non-randomized study from a tertiary center. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(3):373–377. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eom BW, Jang JY, Lee SE, Han HS, Yoon YS, Kim SW. Clinical outcomes compared between laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(5):1334–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9660-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura Y, Uchida E, Aimoto T, Matsumoto S, Yoshida H, Tajiri T. Clinical outcome of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:35–41. doi: 10.1007/s00534-008-0007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SC, Park KT, Hwang JW, Shin HC, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim MH, Han DJ. Comparative analysis of clinical outcomes for laparoscopic distal pancreatic resection and open distal pancreatic resection at a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2261–2268. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9973-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kooby DA, Gillespie T, Bentrem D, Nakeeb A, Schmidt MC, Merchant NB, Parikh AA, Martin RCG, Scoggins CR, Ahmad S, Kim HJ, Park J, Johnston F, Strouch MJ, Menze A, Rymer J, McClaine R, Strasberg SM, Talamonti MS, Staley CA, McMasters KM, Lowy AM, Byrd-Sellers J, Wood WC, Hawkins WG. Left-sided pancreatectomy: a multicenter comparison of laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg. 2008;248:438–443. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185a990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melotti G, Butturini G, Piccoli M, Casetti L, Bassi C, Mullineris B, Lazzaretti MG, Pederzoli P. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: Results on a consecutive series of 58 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;246:77–82. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000258607.17194.2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunha AS, Rault A, Beau C, Laurent C, Collet D, Masson B. A single-institution prospective study of laparoscopic pancreatic resection. Arch Surg. 2008;143:289–295. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor C, O’Rourke N, Nathanson L, Martin I, Hopkins G, Layani L, Ghusn M, Fielding G. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: the Brisbane experience of forty-six cases. HPB. 2008;10:38–42. doi: 10.1080/13651820701802312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khanna A, Koniaris LG, Nakeeb A, Schoeniger LO. Laparoscopic spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:733–738. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pryor A, Means JR, Pappas TN. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy with splenic preservation. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2326–2330. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9403-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruzoni M, Sasson AR. Open and laparoscopic spleen-preserving, splenic vessel-preserving distal pancreatectomy: indications and outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1202–1206. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0512-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoup M, Brennan MF, McWhite K, Leung DHY, Klimstra D, Conlon KC. The value of splenic preservation with distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 2002;137:164–168. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richardson DQ, Scott-Conner CE. Distal pancreatectomy with and without splenectomy: a comparative study. Am Surg. 1989;55:21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aldridge MC, Williamson RCN. Distal pancreatectomy with and without splenectomy. Br J Surg. 1991;78:976–979. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Benoist S, Dugue L, Sauvanet A, Valverde A, Mauvais F, Paye F, Farges O, Belghiti J. Is there a role of preservation of the spleen in distal pancreatectomy? J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188(3):255–260. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00299-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fernández-Cruz L, Blanco L, Cosa R, Rendón H. Is laparoscopic resection adequate in patients with neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors? World J Surg. 2008;32:904–917. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pierce RA, Spitler JA, Hawkins WG, Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Halpin VJ, Eagon JC, Brunt LM, Frisella MM, Matthews BD. Outcomes analysis of laparoscopic resection of pancreatic neoplasms. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(4):579–586. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9022-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Pedrazzoli S. Ductal adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:267–271. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumoto T, Shibata K, Ohta M, Iwaki K, Uchida H, Yada K, Mori M, Kitano S. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy and open distal pancreatectomy: a nonrandomized comparative study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:340–343. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181705d23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kooby DA, Hawkins WG, Schmidt CM, Weber SM, Bentrem DJ, Gillespie TW, Sellers JB, Merchant NB, Scoggins CR, Martin RC, 3rd, Kim HJ, Ahmad S, Cho CS, Parikh AA, Chu CK, Hamilton NA, Doyle CJ, Pinchot S, Hayman A, McClaine R, Nakeeb A, Staley CA, McMasters KM, Lillemoe KD. A multicenter analysis of distal pancreatectomy for adenocarcinoma: is laparoscopic resection appropriate? J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:779–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]