Abstract

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (4th ed. [DSM–IV]; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) distinction between clinical disorders on Axis I and personality disorders on Axis II has become increasingly controversial. Although substantial comorbidity between axes has been demonstrated, the structure of the liability factors underlying these two groups of disorders is poorly understood. The aim of this study was to determine the latent factor structure of a broad set of common Axis I disorders and all Axis II personality disorders and thereby to identify clusters of disorders and account for comorbidity within and between axes. Data were collected in Norway, through a population-based interview study (N = 2,794 young adult twins). Axis I and Axis II disorders were assessed with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) and the Structured Interview for DSM–IV Personality (SIDP–IV), respectively. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were used to investigate the underlying structure of 25 disorders. A four-factor model fit the data well, suggesting a distinction between clinical and personality disorders as well as a distinction between broad groups of internalizing and externalizing disorders. The location of some disorders was not consistent with the DSM–IV classification; antisocial personality disorder belonged primarily to the Axis I externalizing spectrum, dysthymia appeared as a personality disorder, and borderline personality disorder appeared in an interspectral position. The findings have implications for a meta-structure for the DSM.

Keywords: DSM–IV, Axis I and II, personality disorders, factor analysis

Since 1980, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) has classified clinical disorders on Axis I and personality disorders on Axis II (American Psychiatric Association, 1980, 1994). The distinction between clinical disorders and personality disorders was primarily based on expert consensus (Trull & Durrett, 2005; Widiger, Simonsen, Krueger, Livesley, & Verheul, 2005). Subsequently, empirical evidence has challenged the validity of this organizing scheme (Ruocco, 2005). Substantial comorbidity across axes is frequently reported (Grilo, McGlashan, & Skodol, 2000; Hawton, Houston, Haw, Townsend, & Harriss, 2003; Oldham et al., 1995; Shea et al., 2004; Skodol et al., 2002). Genetic and environmental risk factors influencing both Axis I and Axis II disorders have been identified (Orstavik, Kendler, Czajkowski, Tambs, & Reichborn-Kjennerud, 2007; Reichborn-Kjennerud, Czajkowski, Torgersen, et al., 2007), suggesting that the co-occurrence may reflect common etiological factors underlying the two types of disorders. Furthermore, personality disorders, which presumably reflect enduring patterns of functioning, show no higher stability than many clinical disorders (Krueger, 2005; Shea & Yen, 2003), and clinicians do not perceive personality disorders as qualitatively different from Axis I disorders (Flanagan & Blash-field, 2006). However, proposed differences between personality disorders and clinical disorders include the early age of onset requirement for a personality disorder diagnosis, substantial effects on everyday functioning, involvement of a sense of self and identity, and presumed poorer self-awareness and lower treatment response in personality disorders (Krueger, 2005; Oldham, 2005; Widiger, 2003). Given the limited evidence for the structural validity of the Axis I and Axis II distinction, a critical question in the revision of the DSM system is whether to retain this conceptualization (Livesley & Jang, 2008).

Several studies have successfully applied factor analysis to identify empirically clusters of disorders and the corresponding latent liability factors (Durrett & Westen, 2005; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005; Krueger, 1999; Krueger & Markon, 2006; Markon, 2010; Rodebaugh, Chambless, Renneberg, & Fydrich, 2005). This liability-spectrum approach to the classification of psychopathology is based on the understanding of mental disorders as manifestations of a limited number of underlying liability factors shared by several disorders (Krueger & Markon, 2006). Comorbidity or co-occurrence between disorders is accounted for by common factors and correlations between factors. The underlying factor structure of a set of disorders might have implications for both our understanding of the etiology of the disorders and their classification.

For common Axis I disorders (not including schizophrenia and other psychoses), factor analyses have identified internalizing and externalizing spectra of disorders influenced by two separate liability factors. The internalizing–externalizing model has been replicated in a number of studies (Kendler, Davis, & Kessler, 1997; Kessler et al., 2005; Krueger, 1999; Krueger & Markon, 2006; Slade & Watson, 2006). The internalizing spectrum includes major depression, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and the phobias. The externalizing spectrum includes drug and alcohol abuse/dependence and conduct disorder. Some studies have suggested two or three subfactors in the internalizing spectrum, differentiating between distress and fear (Krueger & Markon, 2006) and also bipolar disorders (Watson, 2005). Despite the strong evidence for a general factor structure for common clinical disorders, thus far a limited number of disorders have been subjected to analysis. Recently, internalizing/emotional disorders and externalizing/disinhibitory disorders have been proposed to represent two major clusters in a meta-structure for DSM–5 (Andrews et al., 2009; Goldberg, Krueger, Andrews, & Hobbs, 2009; Krueger & South, 2009).

Results from factor analyses of Axis II disorders are somewhat more divergent, with studies suggesting three to five underlying factors (Rodebaugh et al., 2005; Sheets & Craighead, 2007; Watson, Clark, & Chmielewski, 2008). Some studies have found support for the DSM–IV classification with three clusters: odd/eccentric (A), dramatic (B), and anxious (C) (Rodebaugh et al., 2005). Other studies have rejected this structure and reported evidence for four or five factors (Austin & Deary, 2000; Mulder & Joyce, 1997; Sheets & Craighead, 2007).

Recently, one study investigated the underlying structure of symptoms of selected Axis I and Axis II disorders in combination (Markon, 2010). Four superordinate factors were identified; internalizing, externalizing, thought disorder, and pathological introversion. At the subordinate level, 20 syndromes were found, some of which corresponded to existing DSM diagnoses and some of which represented new syndromal types. Another recent study (Kendler et al., 2010) identified four genetic and three environmental factors underlying a set of syndromal and subsyndromal Axis I and Axis II disorders.

Both Axis I and Axis II disorders are substantially related to normal traits as defined in the five-factor model of personality (Saulsman & Page, 2004; Trull & Sher, 1994; Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009). For example, the trait of neuroticism is associated with a spectrum of internalizing clinical disorders such as depression, anxiety, anorexia, panic disorders, and phobias (Clark, Watson, & Mineka, 1994; Hettema, Neale, Myers, Prescott, & Kendler, 2006; Lahey, 2009). Correspondingly, neuroticism, and partly low agreeableness and conscientiousness, seem to be common denominators for a range of personality disorders (Saulsman & Page, 2004), and integrative models of normal personality traits and disorders recently have been proposed (DeYoung, 2006; Digman, 1997; Markon, Krueger, & Watson, 2005; Watson et al., 2008; Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2009). Despite knowledge of common factors for Axis I and Axis II disorders in terms of personality traits, little is known about the structure of comorbidity patterns of the two axes in combination.

Thus, previous research has delineated the underlying factor structure of common Axis I disorders as well as that of Axis II disorders, and substantial associations between normal personality traits and disorders have been established. Yet, current knowledge has some important limitations. Studies of large population-based samples are limited, and many studies rely on questionnaire measures rather than diagnostic interviews. Although the use of factor analysis of disorder groups has proved successful, most studies typically have been able to include only a limited group of disorders. A major challenge relates to the question of the joint structure of Axis I and Axis II disorders. Previous studies have investigated the underlying factor structure within each of the axes, but to our knowledge no studies have examined the phenotypic structure of a broad set of both common clinical disorders and personality disorders, as outlined in the DSM–IV. Clarifying the joint structure across axes would have potential implications both for our understanding of the etiology of mental disorders and for the revision of classification systems such as the DSM. If the underlying structure involves a clear distinction between personality disorders and clinical disorders, this would provide empirical support for retaining the Axis I–Axis II distinction. Alternatively, if disorders from both axes reflect the same underlying latent factor or factors, a revision of the Axis I–Axis II distinction might be supported.

The aim of this study was to investigate the joint phenotypic structure of a broad set of DSM–IV Axis I and Axis II disorders. By analyzing the pattern of co-occurrence, we sought to determine the number and nature of latent liability factors accounting for comorbidity within and across axes and to determine the location of specific disorders within this structural system.

Method

Participants for the study were recruited from the Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel (Harris, Magnus, & Tambs, 2002, 2006). Twins were identified through the Norwegian National Medical Birth Registry, which receives mandatory notification of all live births. The panel includes the entire cohort of twins born in Norway between 1967 and 1979 (N = 15,370). Two questionnaire studies (Q1 and Q2) were conducted in 1992 and 1998. Altogether 8,045 twins participated in the 1998 survey. The Twin Panel has been described in detail elsewhere (Harris et al., 2002, 2006; Tambs et al., 2009).

The present study is based on interview data, collected between 1999 and 2004. Participants were recruited among 3,153 complete twin pairs who participated in the Q2 study, and 68 pairs were drawn directly from the Twin Panel. Only pairs in which both twins agreed to participate were included. Of the eligible twins, a total of 2,794 (44%) twins participated in the interviews assessing Axis I and II disorders. Nonparticipants included persons unwilling or unable to participate (0.8%), twin pairs in which only one twin agreed to participate (16.2%), and persons who did not respond after one reminder (38.2%). The interview participants did not differ from nonparticipants on a checklist of symptoms of anxiety and depression (Hopkins Symptom Checklist 5; Tambs & Moum, 1993) or other health indicators included in the Q2 survey (Tambs et al., 2009).

Interviews were mainly conducted face-to-face. For practical reasons, 231 participants were interviewed by telephone. The interviewers were mostly psychology students in their final part of training or experienced psychiatric nurses. All received a standardized training program by professionals with extensive experience with the instruments and were supervised during the data collection. The mean age of the participants was 28.2 years (range = 19–36 years), and 63% were female. Several articles describing details of the sample and the measures used in this report have been published (Kendler et al., 2008; Orstavik et al., 2007; Reichborn-Kjennerud, Czajkowski, Neale, et al., 2007).

Approval was received from The Norwegian Data Inspectorate and the Regional Ethical committee, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants after complete description of the study.

Measures

Axis I

Disorders on Axis I were assessed with a computerized version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Wittchen & Pfister, 1997), developed by the World Health Organization and used worldwide in major psychiatric surveys in recent years. This instrument has been shown to have good test–retest and interrater reliability (Wittchen, 1994). The following 14 disorders were included in the present investigation: major depressive disorder, dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia, specific phobia (animal, natural environment, blood–injection–injury, situational, or other), panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, anorexia nervosa, pain disorder, conduct disorder, alcohol abuse/dependence, cannabis abuse/dependence, and hard drugs abuse/dependence (including opiates, sedatives, cocaine, amphetamine, hallucinogens, inhalants, polysubstance).

Axis I diagnoses were assigned without hierarchical rules in order to examine co-occurrence without exclusions, in accordance with previous studies (Kendler, Aggen, Tambs, & Reichborn-Kjennerud, 2006; Kessler et al., 2005). For all clinical disorders, lifetime prevalence was used to allow for a time frame corresponding to that used for the personality disorders.

Axis II

A Norwegian version of the Structured Interview for DSM–IV Personality Disorders (SIDP–IV; Pfohl & Zimmerman, 1995) was used to assess the personality disorders. This instrument is a comprehensive semistructured diagnostic interview for the assessment of DSM–IV Axis II diagnoses. The SIDP was initially developed in 1983 and has been used in a number of studies in several countries, including Norway (Helgeland, Kjelsberg, & Torgersen, 2005; Torgersen, Kringlen, & Cramer, 2001). The instructions for the SIDP–IV specify a 5-year rule, which means that behavior typical of the past 5 years represents the basis for the ratings, thus capturing the general chronicity feature of personality disorders. All 10 DSM–IV personality disorders were used in the analyses. In addition, depressive personality disorder, listed in Appendix B of the DSM–IV, was included, as there is substantial interest in determining its nature (Krueger, 2005; Widiger, 2003). In line with previous analyses (Kendler et al., 2008), we only used Criterion A for antisocial personality disorder. Conduct disorder was included as a separate Axis I disorder.

The specific DSM–IV criteria for personality disorders were rated as follows: 0 = absent; 1 = subthreshold; 2 = present; and 3 = strongly present. The number of criteria for each personality disorder varies from seven to nine. In this population-based sample, the prevalence rates for categorically defined diagnoses were too low to permit reliable analyses. Thus, to retain sufficient information, we modeled personality disorders as dimensional traits operationalized as the number of endorsed criteria. Sum scores of subthreshold (≥1) criteria were calculated for each disorder. To test the assumption that intermediate scores represent a position on an underlying continuum from no symptoms to full disorder, we have previously conducted multiple threshold tests for each disorder. The multiple threshold model fit well in all analyses (Kendler et al., 2008; Kendler, Czajkowski, et al., 2006; Reichborn-Kjennerud, Czajkowski, Neale, et al., 2007). We also estimated polychoric correlations between the sum scores and full diagnoses for each disorder. Correlations were as follows: paranoid personality disorder, .93; schizoid personality disorder, 1.0; schizotypal personality disorder, .90; histrionic personality disorder, .84; borderline personality disorder, .90; antisocial personality disorder, .97; narcissistic personality disorder, .76; avoidant personality disorder, .95; dependent personality disorder, .90; obsessive–compulsive personality disorder, .82; and depressive personality disorder, .93.

Interrater reliability of the measures was assessed by two raters’ scoring of 70 audiotaped interviews. As none of the respondents in the reliability sample obtained full diagnoses, kappas could not be calculated. However, the intraclass (and polychoric) correlations for the number of endorsed criteria were as follows: paranoid personality disorder, .92 (.94); schizoid personality disorder, .81 (.86); schizotypal personality disorder, .86 (.90); histrionic personality disorder, .85 (.80); borderline personality disorder, .93 (.94); antisocial personality disorder, .91 (.94); narcissistic personality disorder, .86 (.82); avoidant personality disorder, .96 (.97); dependent personality disorder, .96 (.99); obsessive–compulsive personality disorder, .92 (.87); and depressive personality disorder, .96 (.97). Finally, we calculated Cronbach’s alphas for the sum scores on the basis of polychoric correlations. Alphas were as follows: paranoid personality disorder, .84; schizoid personality disorder, .77; schizotypal personality disorder, .75; histrionic personality disorder, .79; borderline personality disorder, .88; antisocial personality disorder, .89; narcissistic personality disorder, .81; avoidant personality disorder, .88; dependent personality disorder, .82; obsessive–compulsive personality disorder, .72; and depressive personality disorder, .87.

Analyses

The analytic strategy involved first applying exploratory factor analyses (EFAs) in one sample to develop a model of the underlying structure and then testing this structure by confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) in a second sample. In the total sample, the twins in each pair were randomly assigned as Twin 1 or Twin 2, thereby providing the basis for Sample 1 and Sample 2. Thus, each sample involved independent observations (no two twins in a pair would be in the same sample), and the two samples were naturally matched with regard to demographic and genetic factors.

In both EFA and CFA, latent continuous factors are hypothesized to account for the pattern of correlations among the observed variables. When EFA is conducted in the framework of structural equation modeling, the analyses produce, as with CFA, parameter estimates, standard errors, model–data misfit, and goodness-of-fit indices as well as indicators of specific areas of misfit (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009; Marsh et al., 2009). The goodness of fit for a certain model reflects the degree to which the model is able to account for the structure of the observed data (Hoyle, 1995). To evaluate model fit, we used the chi-square value, the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA; Bollen & Curran, 2006; Hoyle, 1995). CFI and TLI scores above .95 indicate good fit. RMSEA scores below .08 are acceptable, and scores below .05 are good (Bollen & Curran, 2006; Brown, 2006). When nested models were compared, we used the chi-square difference test. The common factor analyses were performed in Mplus, with the weighted least squares means and variance adjusted (WLSMV) algorithm (Muthén & Muthén, 2006). The WLSMV estimator is appropriate for categorical and nonmultivariate normal data. (Note that the WLSMV provides estimated chi-square values and degrees of freedom; thus, the chi-square difference test cannot be performed directly on the resulting values but requires the use of the DIFFTEST procedure in Mplus). A number of options are available for rotating the factor structure extracted in an EFA (Browne, 2001; Fabrigar, Wegener, MacCallum, & Strahan, 1999). We used geomin rotation, which is the recommended approach in Mplus (www.statmodel.com).

Given the categorical nature of the data and the skewed distribution, we estimated tetrachoric/polychoric correlations between all variables. Based on the assumptions of a liability-threshold model, polychoric correlations are estimates of the true Pearson correlations between the normally distributed latent variables that are assumed to give rise to the observed categorical variables. In this formulation, a threshold is estimated on the latent variable that distinguishes between each of the ordinal categories.

Whereas the EFA is designed to explore the number and nature of the underlying factors, the CFA tests models that specify an a priori hypothesized structure. One of the strengths of CFA is the possibility of controlling for background variables and method factors. Given that sex and age represent potential confounders contributing to the pattern of correlations, in the CFAs all disorders were regressed on sex and age simultaneously with the testing of the factor model. Further, given that differences between the CIDI and the SIDP–IV, as well as different scoring methods used, might contribute to the pattern of correlations, we modeled separate method factors for Axis I and Axis II disorders. Thus, one factor had loadings from all of the Axis I disorders, and another factor had loadings from all of the Axis II disorders. Method factor loadings were constrained to be equal within each factor, and the factors were modeled as orthogonal to other factors.

Results

Tetrachoric/polychoric correlations were estimated for the full set of 25 disorders. Table 1 shows all correlations for the full sample. Correlations ranged from −.17 to .85. In total, 96.7% of the correlations were positive. Substantial correlations were observed both within and between axes. Some disorders showed a differentiated pattern of correlations, whereas others, such as borderline personality disorder, showed substantial correlations with most other disorders.

Table 1.

Polychoric Correlations Between 25 Axis I and Axis II Disorders

| Disorder | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Major depressive disorder | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Generalized anxiety disorder | .52 | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Social phobia | .44 | .52 | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Agoraphobia | .38 | .51 | .63 | — | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Specific phobia | .33 | .38 | .38 | .39 | — | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Dysthymia | .36 | .40 | .54 | .28 | .26 | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Panic disorder | .43 | .56 | .57 | .80 | .33 | .46 | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Pain disorder | .22 | .17 | .34 | .27 | .28 | .34 | .26 | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 9. Anorexia | .16 | .36 | .17 | .07 | .26 | .14 | .26 | .19 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. Posttraumatic stress disorder | .51 | .30 | .47 | .60 | .30 | .38 | .52 | .34 | .25 | — | |||||||||||||||

| 11. Alcohol abuse/dependence | .19 | .20 | .30 | .26 | .10 | .18 | .23 | .03 | .03 | .26 | — | ||||||||||||||

| 12. Cannabis abuse/dependence | .10 | .02 | .32 | .26 | .09 | .27 | .41 | −.17 | .08 | .29 | .62 | — | |||||||||||||

| 13. Hard drug abuse/dependence | .16 | .13 | .15 | .46 | .04 | .39 | .36 | −.17 | −.05 | .25 | .46 | .85 | — | ||||||||||||

| 14. Conduct disorder | .16 | .13 | .07 | .12 | .03 | .21 | .32 | −.11 | −.10 | .16 | .49 | .61 | .60 | — | |||||||||||

| 15. Paranoid personality disorder | .30 | .26 | .37 | .31 | .21 | .34 | .32 | .15 | .11 | .31 | .20 | .17 | .25 | .14 | — | ||||||||||

| 16. Schizoid personality disorder | .18 | .14 | .23 | .15 | .08 | .45 | .17 | .10 | .03 | .24 | .03 | .12 | .14 | .14 | .32 | — | |||||||||

| 17. Schizotypal personality disorder | .30 | .22 | .32 | .34 | .26 | .46 | .40 | .23 | .05 | .40 | .07 | .15 | .23 | .20 | .58 | .49 | — | ||||||||

| 18. Antisocial personality disorder | .25 | .26 | .22 | .14 | .08 | .28 | .22 | −.09 | −.06 | .25 | .48 | .70 | .71 | .67 | .29 | .19 | .26 | — | |||||||

| 19. Borderline personality disorder | .47 | .36 | .45 | .38 | .26 | .54 | .43 | .16 | .19 | .51 | .38 | .39 | .46 | .43 | .49 | .29 | .45 | .51 | — | ||||||

| 20. Histrionic personality disorder | .19 | .17 | .21 | .17 | .18 | .18 | .21 | .07 | .13 | .27 | .16 | .15 | .18 | .21 | .44 | .18 | .37 | .34 | .49 | — | |||||

| 21. Narcissistic personality disorder | .19 | .10 | .12 | .10 | .11 | .16 | .14 | −.03 | −.02 | .16 | .27 | .18 | .21 | .27 | .42 | .29 | .35 | .43 | .42 | .51 | — | ||||

| 22. Dependent personality disorder | .21 | .31 | .30 | .37 | .20 | .42 | .33 | .02 | .21 | .25 | .17 | .14 | .01 | .14 | .36 | .27 | .43 | .21 | .47 | .35 | .34 | — | |||

| 23. Avoidant personality disorder | .26 | .32 | .42 | .38 | .18 | .48 | .32 | .11 | .12 | .29 | .14 | .15 | .13 | .09 | .37 | .42 | .43 | .16 | .38 | .13 | .26 | .56 | — | ||

| 24. Obs.-comp. personality disorder | .19 | .20 | .18 | .25 | .15 | .14 | .20 | .10 | .09 | .31 | .09 | −.06 | .13 | .08 | .39 | .26 | .34 | .21 | .33 | .36 | .41 | .24 | .23 | — | |

| 25. Depressive personality disorder | .43 | .49 | .50 | .48 | .29 | .59 | .43 | .13 | .24 | .38 | .14 | .16 | .17 | .09 | .46 | .28 | .43 | .24 | .51 | .32 | .32 | .51 | .55 | .37 | — |

Note. For total sample, N = 2,794. Obs.-comp. = Obsessive-compulsive

Exploratory Factor Analysis

An EFA was performed on the full set of disorders in Sample 1. The eigenvalues for the first six factors before rotation were, respectively: 7.97, 3.14, 2.00, 1.49, 1.16, and 1.02. Parallel analysis (Hayton, Allen, & Scarpello, 2004) indicated four clear factors, with the fifth factor close to trivial (mean random eigen-value = 1.14). The scree plot also suggested four factors. Fit statistics from the EFA showed that the four-factor model fitted very well, χ2(85, N = 1,395) = 183.67, CFI = .97, TLI = .98, RMSEA = 0.029; accounted for 52% of the variance of the disorders; and was superior to the three-factor model (p < .001). The four-factor model thus reflected a parsimonious representation of the general underlying structure of all included disorders.

Inspection of the five-factor model indicated possible overextraction in that model. The fifth factor was mainly due to a correlation between schizoid and schizotypal personality disorder, which also share one criterion in the DSM–IV (lack of close friends). Hence, the content of the factors in the five-factor solution lends support to the four-factor model as well fitting and sufficient.

The factor structure for the four-factor model is shown in Table 2. Loadings >.30 are presented in boldface. The first factor contained primarily Axis I disorders: anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, dysthymia, anorexia nervosa, posttraumatic stress disorder, and pain disorder. In addition, depressive and borderline personality disorder loaded partly on this factor. We labeled this factor Internalizing. The second factor comprises hard drugs, cannabis, and alcohol dependence/abuse, conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and in part borderline personality disorder. This factor was labeled Externalizing. The third factor included only personality disorders, with a predominance of Cluster A and B disorders (histrionic, narcissistic, paranoid, schizotypal, obsessive–compulsive, and borderline personality disorders). We chose to label this factor Cognitive–Relational Disturbance. The fourth factor contained personality disorders from Cluster C (avoidant and dependent personality disorders) and also included loadings from schizoid personality disorder, depressive personality disorder, and dysthymia. We suggest the label Anhedonic Introversion for this factor.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings From Exploratory Factor Analysis: Geomin Rotation for Sample 1

| Disorder | Factor 1: Internalizing | Factor 2: Externalizing | Factor 3: Cognitive–Relational Disturbance | Factor 4: Anhedonic Introversion | Communalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panic disorder | .80 | .07 | −.12 | .07 | .67 |

| Agoraphobia | .73 | .03 | −.16 | .27 | .72 |

| Generalized anxiety | .70 | −.08 | .05 | −.01 | .50 |

| Social phobia | .60 | .06 | .00 | .24 | .57 |

| Major depression | .59 | .07 | .13 | −.08 | .39 |

| Pain disorder | .59 | −.26 | .03 | −.13 | .31 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | .56 | −.02 | .21 | .05 | .47 |

| Specific phobia | .46 | −.07 | .11 | −.11 | .21 |

| Dysthymia | .41 | .10 | .05 | .38 | .53 |

| Anorexia | .41 | −.11 | −.02 | −.06 | .14 |

| Cannabis abuse/dependence | .07 | .89 | −.03 | .04 | .83 |

| Hard drug abuse/dependence | .06 | .88 | −.06 | .16 | .86 |

| Conduct disorder | −.09 | .73 | .22 | −.08 | .57 |

| Antisocial personality disorder | −.03 | .72 | .36 | −.07 | .69 |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | .10 | .52 | .13 | −.03 | .34 |

| Narcissistic personality disorder | −.20 | .20 | .71 | .03 | .53 |

| Histrionic personality disorder | .10 | .08 | .65 | −.13 | .44 |

| Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder | −.04 | −.07 | .59 | .07 | .36 |

| Paranoid personality disorder | .15 | −.01 | .55 | .16 | .49 |

| Schizotypal personality disorder | .23 | −.12 | .45 | .26 | .51 |

| Borderline personality disorder | .31 | .34 | .39 | .11 | .63 |

| Avoidant personality disorder | −.05 | −.02 | .05 | .91 | .82 |

| Dependent personality disorder | .08 | .03 | .22 | .52 | .47 |

| Schizoid personality disorder | .04 | −.04 | .24 | .37 | .28 |

| Depressive personality disorder | .32 | .00 | .28 | .37 | .56 |

| Factor correlations | |||||

| Factor 2 | .23 | ||||

| Factor 3 | .35 | .15 | |||

| Factor 4 | .47 | .15 | .37 | ||

Note. For Sample 1, N = 1,395. Loadings >.30 are significant and presented in boldface.

In general, the structure identified was relatively simple, with few cross-loadings exceeding .30 and none exceeding .40. Among the cross-loadings, in particular, the role of borderline personality disorder is noteworthy. Borderline personality disorder loaded on both the Internalizing and Externalizing factors (Axis I), in addition to loading on the Cognitive–Relational Disturbance factor (Axis II). Dysthymia and depressive personality disorder were located in an intermediate position, with loadings on both the Internalizing and Anhedonic Introversion factors.

Given that solutions other than the four-factor model can be informative of higher order structures, we provide a brief outline of the one-, two-, and three-factor solutions. The one-factor solution did not fit well, χ2(92, N = 1,395) = 645.46, RMSEA = 0.066, CFI = .85, TLI = .88. Although a single factor is not able to account for the observed data structure, it is worth noting that the highest loading disorder on this general factor of pathology was borderline personality disorder (.73).

In the two-factor model, χ2(91, N = 1,395) = 385.64, RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = .92, TLI = .93, one broad internalizing factor was extracted, including Axis I disorders—major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, phobias, panic, dysthymia, pain disorder, anorexia, and posttraumatic stress disorder—and Axis II disorders—paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, dependent, obsessive–compulsive, and depressive personality disorders. The second factor included externalizing disorders, with predominant loadings from several Axis I disorders—alcohol abuse/dependence, conduct disorder, cannabis and hard drugs abuse/dependence—and Axis II disorders—antisocial, narcissistic, and histrionic personality disorders.

In the three-factor model, χ2(90, N = 1,395) = 254.35, RMSEA = 0.036, CFI = .96, TLI = .96, a separate personality disorder factor was extracted (including paranoid, narcissistic, histrionic, and obsessive–compulsive personality disorders), in addition to an internalizing factor (which included dependent, depressive, and avoidant personality disorders), and an externalizing Axis I factor (including antisocial personality disorder).

Confirmatory Factor Analyses

The findings from the EFAs in Sample 1 were tested in CFAs in Sample 2. In the first set of analyses, we tested simple structure models with no cross-loadings, assigning disorders only to the latent factor for which they had the highest loading in the EFA. All models included two orthogonal method factors, and all observed variables were regressed on sex and age simultaneously with testing of the factor structure. In addition, correlated residuals between schizoid and schizotypal personality disorders were allowed because of their sharing of one diagnostic criterion.

As a base model, we first tested a structure with only the method factors and no substantive factors. This model did not fit the data (Table 3, Model 1). Next, we tested the –one-factor through four-factor models as derived from the EFAs. Table 3 shows the fit of the models. By all fit measures, the models showed successively improved fit with increased numbers of factors. The chi-square difference tests also showed significant improvements in fit for each added factor. Thus, the CFAs supported the four-factor model identified with EFA, and an acceptable fit was obtained with a simple structure model with no cross-loadings.

Table 3.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of 25 Axis I and Axis II Disorders: Fit of Models

| Model | χ2 | df | p (Δχ2 test) | CFI | TLI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Only method factors | 1,364.46 | 77 | .69 | .65 | .109 | |

| 2. One factor | 568.85 | 96 | <.001 | .89 | .90 | .059 |

| 3. Two factors | 424.50 | 95 | <.001 | .92 | .93 | .050 |

| 4. Three factors | 393.55 | 93 | <.001 | .93 | .93 | .048 |

| 5. Four factors | 313.14 | 93 | <.001 | .95 | .95 | .041 |

| 6. Four factors, three cross-loadings | 247.64 | 91 | <.001 | .96 | .96 | .035 |

Note. For Sample 2, N = 1,399. All models included two orthogonal method factors, and the observed variables were regressed on sex and age simultaneously with testing of the factor model. With the weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator, the chi-square and degrees of freedom were estimated rather than calculated. The appropriate DIFFTEST procedure in Mplus was applied to perform the Δχ2 test. CFI = comparative fit index; TLI = Tucker–Lewis index; RMSEA = root-mean-square error of approximation.

However, because of evidence from the EFA of substantial cross-loadings (>.30) for a few disorders, as a final step, we tested adjustments of the model by including these cross-loadings. Five cross-loadings (see Table 2) were included. Four of these showed significant (p < .01) effects in the CFA, that is, borderline personality disorder loaded on both the Internalizing and Externalizing factors, and depressive personality disorder loaded on the Internalizing factor. Dysthymia loaded on the Anhedonic Introversion factor, but not on the Internalizing factor. The loading of antisocial personality disorder on Cognitive–Relational Disturbance was not confirmed (the results were nonsignificant). The model with three remaining cross-loadings (Model 6, Table 3) yielded further improvement in fit, Δχ2 (Δdf = 3), = 105.37, p < .001, as compared with the simple structure model.

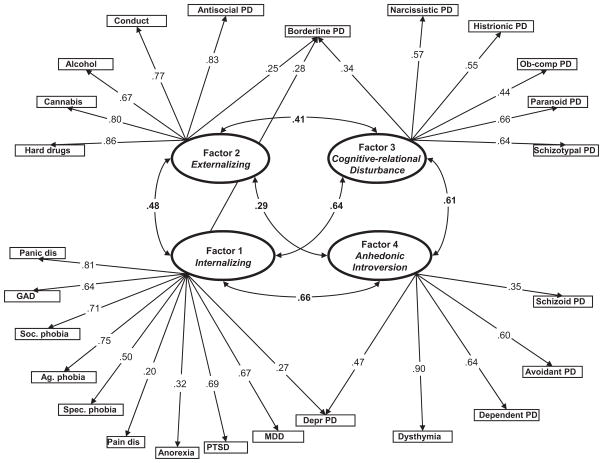

Figure 1 shows this final model, with factor loadings and factor correlations. The correlations ranged from .29 for Externalizing and Anhedonic Introversion to .66 for Internalizing and Anhedonic Introversion. The two method factors (not shown in the figure) yielded loadings of .21 (Axis I) and .34 (Axis II). Thus, although the method factors alone were not able to account for the observed data (Model 1, Table 3), the factors contributed systematically to the data structure. With regard to sex and age, in the final model the regression coefficients for sex (male = 0, female = 1) ranged from −.27 (alcohol abuse/dependence) to .41 (anorexia) and for age from −.12 (hard drugs abuse/dependence) to .08 (generalized anxiety). Thus, whereas age differences were relatively minor, the sex effects clearly were of such a magnitude that controlling for the effects was warranted.

Figure 1.

Final confirmatory factor analysis model. For Sample 2, N = 1,399: χ2(91) = 247.64, root-mean-square error of approximation = .035; comparative fit index = .96, Tucker–Lewis index = .96. Method factors for Axis I and Axis II disorders were included in the analysis, and all observed variables were regressed on age and sex (not shown in figure). PD = personality disorder; dis = disorder; GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; Soc. phobia = social phobia; Ag. phobia = agoraphobia; Spec. phobia = specific phobia; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; MDD = major depressive disorder; Depr = depressive; Ob-comp = Obsessive–compulsive. p < .01 for all loadings and correlations.

In summary, the preliminary evidence of four general factors in the Sample 1 EFA was replicated in the sample 2 CFAs. In addition, three cross-loadings were confirmed. The four-factor model accounted for the covariance structure of the 25 disorders to a high extent. Factor loadings for the individual disorders were generally high (all ps < .001) with a mean of .58, and all factors were positively correlated.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to investigate the structure of latent factors underlying a broad set of DSM–IV Axis I and Axis II disorders and thereby to identify clusters of disorders for which the comorbidity is accounted for by underlying liability factors.

The Four-Factor Model

Four groups of disorders were identified. In accordance with previous studies, we found common Axis I disorders to sort rather clearly into internalizing and externalizing spectra (Goldberg et al., 2009; Krueger, Markon, Patrick, Benning, & Kramer, 2007; Krueger & South, 2009). Our analyses included a broad set of disorders and, as such, the findings represent an expanded replication of earlier findings. The internalizing spectrum contained anxiety disorders, major depression, anorexia, pain disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Negative affectivity represents a common feature of these disorders (Goldberg et al., 2009; Krueger, 2005; Watson, 2005). In contrast to some previous studies (Krueger, 1999; Slade & Watson, 2006), we did not find subfactors reflecting distress versus fear within the internalizing spectrum. Rather, at this general level, these disorders share a common liability. Further, disorders varied in the degree to which they reflected the core characteristics of the cluster. For example, panic disorder and social phobia represent quintessential disorders of this spectrum, whereas anorexia nervosa and pain disorder represent more peripheral disorders.

The externalizing spectrum comprised mainly Axis I disorders such as substance use disorders and conduct disorder. Common features of this spectrum include disinhibition and impulsivity (Krueger et al., 2007; Krueger & South, 2009). In addition to the Axis I disorders, antisocial personality disorder also belonged to the externalizing spectrum. The close link between antisocial per sonality disorder and Axis I externalizing disorders accords with previous findings (Kendler et al., 1997; Krueger et al., 2007) However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to clearly show that antisocial personality disorder is more strongly related to the externalizing Axis I spectrum than to the personality disorder dimensions.

The two remaining clusters were dominated by Axis II disorders. We suggest the terms Anhedonic Introversion and Cognitive–Relational Disturbance. There are notable differences between this structure and the cluster structure of DSM–IV. The Anhedonic Introversion spectrum comprised personality disorders from Cluster C (dependent and avoidant personality disorders), Cluster A (schizoid personality disorder), and depressive personality disorder and dysthymia. Characteristics for this spectrum include inhibition, withdrawal, helplessness, lack of positive affect, and presence of negative affect. Thus, the spectrum can be seen as containing internalizing personality disorders.

The Cognitive–Relational Disturbance spectrum is dominated by Cluster B disorders (histrionic, narcissistic, and borderline personality disorders) and Cluster A disorders (paranoid and schizotypal personality disorders) in addition to obsessive–compulsive personality disorder (Cluster C). Core features include relational conflict, disinhibition, preoccupation, antagonizing, dramatizing, oddness, and thought disturbance. To some extent, the spectrum includes externalizing types of personality disorders.

In an attempt to explore the feasibility of a new meta-structure for DSM, Andrews et al. (2009) identified paranoid, histrionic, narcissistic, and obsessive–compulsive personality disorders as disorders “not yet assigned.” Several previous models of abnormal and normal personality have failed to represent the “odd” disorders adequately (Watson et al., 2008). Our findings suggest that these disorders share an underlying liability, partly characterized by an expressive form of thought disturbance and interpersonal conflict.

Previous studies have typically reported three or four underlying personality disorder factors, with limited support for the DSM structure of the A, B, and C clusters (Livesley, Jang, & Vernon, 1998; Sheets & Craighead, 2007; Yang, Bagby, Costa, Ryder, & Herbst, 2002). Our results suggest three factors, that is, two primary personality disorder factors, with the addition of a third factor that influences antisocial and borderline personality disorders and that is identical to the Externalizing factor (Axis I) Previous analyses of the same data set have revealed a separate genetic factor influencing borderline and antisocial personality disorders (Kendler et al., 2008). Prior studies also suggest a clear familial aggregation of the two personality disorders (White, Gunderson, Zanarini, & Hudson, 2003). Our findings add to this by demonstrating the specific phenotypic link to the Axis I externalizing liability.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the joint phenotypic structure of a broad set of disorders from Axes and II. However, a noteworthy account of the combined structure of the symptom level has recently been provided (Markon, 2010) Markon developed a hierarchical model, with 20 subordinate dimensions of psychopathology and four higher order factors; Internalizing, Externalizing, Pathological Introversion, and Thought Disorder. The former three factors are highly similar to three of the factors in our model, although we chose the term Anhedonic Introversion rather than pathological introversion. The Thought Disorder factor of Markon’s model has a somewhat weaker resemblance to our Cognitive–Relational Disturbance factor. Thus, on the basis of different data sets and different variables (disorders vs. symptoms), these two studies partly point in the same direction, converging on the essence of some major clusters of disorders while also providing some diverging results.

Another recent study, based on a subsample of the current sample and a related set of disorders, found four genetic and three environmental factors underlying the disorders (Kendler et al., 2010). The genetic structure resembles the currently identified phenotypic structure, suggesting that the phenotypic four-factor model is primarily driven by genetic factors.

A final point on the four-factor model is that although this model fit best by all measures, it is noteworthy that the two-factor model also yielded reasonably good fit. This model involved a distinction between broad classes of internalizing and externalizing disorders, each including both clinical and personality disorders. Thus, at a general level, internalizing–externalizing can be seen as a broad structure within which our four-factor model is embedded.

Location of Individual Disorders

One important aspect of these findings concerns the location of the individual disorders. To a certain degree, the placement of the disorders was consistent with the DSM–IV classification, and the analyses revealed a fairly simple structure of groups of disorders. Yet, despite high intraspectrum coherence, that is, most disorders belonging to only one spectrum, there were some important exceptions. In line with previous findings of high comorbidity between borderline personality disorder and Axis I disorders (James & Taylor, 2008; Ruocco, 2005; Slade, 2007), our analyses revealed a link between borderline personality disorder and both the internalizing and externalizing (Axis I) clusters, which was not seen for the other personality disorders. Although previous confirmatory factor analytic studies consistently have found that borderline personality disorder is a unidimensional structure, that is, that its nine criteria identify a relatively coherent single factor (Aggen, Neale, Røysamb, Reichborn-Kjennerud, & Kendler, 2009; Johansen, Karterud, Pedersen, Gude, & Falkum, 2004; Sanislow et al., 2002), the disorder can be seen as multidimensional in the sense of not being seated in a single diathesis (Paris, 2007). Borderline personality disorder appears to be affected by several liabilities and could be considered interspectral in nature. As currently defined (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), borderline personality disorder emerges as a combined result of high vulnerabilities for Axis I and Axis II dispositions. Alternatively, the borderline diagnosis can be seen as too heterogeneous, and the findings might point to a need for a more narrow set of criteria for the disorder.

In addition, depressive personality disorder, which is currently placed in the Appendix of DSM–IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Widiger, 2003), revealed substantial cross-loadings and remains in an intermediate position between clinical disorders and personality disorders. Our analyses also indicate that dysthymia primarily belongs to a personality disorder cluster. In contrast, and as discussed above, antisocial personality disorder reveals a location among Axis I externalizing disorders.

Comorbidity Within and Across Axes

Another noteworthy aspect of the results concerns the origins of patterns of comorbidity. A model of four latent liability factors accounted for the majority of the co-occurrence observed between the 25 disorders examined. As such, it represents a parsimonious model of the underlying joint structure of clinical disorders and personality disorders. Each liability factor accounted for the co-occurrence among disorders within its corresponding spectrum (in addition to the covariance accounted for by the method factors included). Co-occurrence across clusters (both within and across the current axis system) was mainly explained by general factors. Thus, these findings imply that comorbidity is generally due to associations between broad liability factors rather than to disorder-specific associations. Previous studies have found associations between selected personality disorders and clinical disorders (e.g. borderline personality disorder and major depressive disorder; avoidant personality disorder and social phobia; Reichborn-Kjennerud, Czajkowski, Torgersen, et al., 2007; Ruocco, 2005; Shea et al., 2004; Skodol et al., 2002). We found no evidence of specific one-to-one comorbidity across axes beyond that accounted for by the general factors. Thus, our results are in line with previous findings of associations between clinical disorders and personality disorders (Ruocco, 2005; Skodol et al., 2002) but suggest that the associations are mainly due to relations at the level of general underlying factors. If the comorbidity across axes is primarily due to general factors, previous findings of one-to-one associations are basically exemplars of a general structure in which the nature of comorbidity is based on the level of broad liability dimensions.

Factor Interrelations

The four factors were all positively correlated, yet a distinct pattern of correlations emerged. The CFA-based correlations were generally higher than the EFA-based correlations. Such a finding is expected, as the EFA also includes a full set of cross-loadings to account for the observed data structure (Asparouhov & Muthen, 2009; Marsh et al., 2009). Despite the magnitude of differences, a similar pattern was observed. The highest correlation was found for Internalizing and Anhedonic Introversion, thus suggesting a general liability to internalizing, or emotional, disorders across the axes. In contrast, the Externalizing factor showed only moderate correlations with the other factors, indicating a high degree of distinctiveness for this liability. The Cognitive–Relational Disturbance factor (Axis II), albeit partly containing externalizing personality disorders, was quite different from the Externalizing factor of Axis I.

In the CFA, method factors were included to account for possible systematic effects of the difference between the CIDI and the SIDP–IV and of different scoring procedures. Relatively small, but significant effects of the method factors were found. Yet, after controlling for method variance, we still found evidence of a distinction between Axis I and Axis II disorders.

Previous studies have repeatedly found two general factors for Axis I disorders: internalizing and externalizing (Kendler, Prescott, Myers, & Neale, 2003; Krueger, Chentsova-Dutton, Markon, Goldberg, & Ormel, 2003; Slade, 2007; Slade & Watson, 2006). Our findings suggest a dual structure with a distinction between Axis I and Axis II disorders as well as between broad groups of internalizing and externalizing disorders.

Limitations

Several limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. Our analyses did not include disorders such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders, as they were too rare in this population-based sample. Despite the advantages of population-based studies in terms of generalizability, the absence of some disorders, and the possible lack of infrequent aspects of other disorders, is inherent in such studies. Thus, the findings are limited to the group of relatively common clinical disorders and personality disorders. Future studies would presumably be able to add other disorders to the model. In particular, we would encourage investigations of the psychotic disorders in which thought disturbance appears to represent a central feature.

The different time frame used for diagnosing clinical disorders and personality disorders might represent a limitation. However, by using a lifetime frame for clinical disorders and a 5-year frame for personality disorders, we believe a fairly high correspondence is obtained that enables us to capture the stable component of the disorders. Personality disorders are defined by such general features as chronicity, early onset, and lack of insight. To some extent, these features are captured by structured interviews such as the SIDP–IV. Nevertheless, population-based studies that include such interviews will contain less information than a full clinical assessment.

The use of a twin sample as representative of the full population might be seen as a limitation. However, studies have shown that twin samples do not differ from other population-based samples (Johnson, Krueger, Bouchard, & McGue, 2002; Kendler & Prescott, 2006). Further, randomly dividing the full twin pair sample into one for exploratory purposes and the other for confirmatory analyses has both advantages and limitations. The two samples are partly matched with regard to background variables and genetic factors, and differences between the two samples would therefore be due to chance characteristics. Nevertheless, replication with other samples is required in order to establish the generalizability of the findings. In addition, we have controlled for mean-level differences between sex and age groups and thereby have identified general structures across sex and age. Yet, the possibility of partly different liability structures for men and women and for various age groups might be of interest for future studies.

Investigating the underlying factor structure of disorders is only one of several approaches for making claims about classification systems. Although we believe the identified liabilities and disorder groups to be important for taxonomies, this does not imply a disregard for other aspects such as etiology, stability, consequences, treatability, and functionality.

Because of low prevalences for personality disorders, we used a dimensional representation that included subthreshold categories. Different scoring methods for Axis I and Axis II disorders could contribute to methodological artifacts in the data pattern. However, psychometrically, this approach is warranted, and we believe the inclusion of method factors in the models takes account of systematic method effects. Finally, substantial attrition was observed in this sample from the birth registry through three waves of contact. We report detailed analyses of the predictors of nonresponse across waves elsewhere (Tambs et al., 2009). Briefly, cooperation was not predicted by symptoms of psychiatric disorders. Further, a series of analyses did not show any evidence of changes in the genetic and environmental covariance structure because of recruitment bias for a broad range of mental health indicators. Although we cannot be certain that our sample was representative with respect to psychopathology, these findings suggest that a substantial bias is unlikely.

Conclusion

On the basis of the pattern of co-occurrence, we conclude that personality disorders and common clinical disorders typically cluster in separate groups. By including a broad set of disorders, the current investigation provides support for a distinction between Axis I and Axis II disorders, and a four-factor model of mental disorders was developed. There were exceptions to the general pattern of coherent groups of disorders and a clear axis division Antisocial personality disorder was located in the Axis I Externalizing cluster, dysthymia was located in the Axis II Anhedonic Introversion cluster, and borderline personality disorder was found to be multifactorial and located in an interspectral position. The findings suggest a dual structure involving both an axis division and a distinction between broad internalizing and externalizing disorders. We believe the results fit with recent efforts to develop a metastructure for DSM (Andrews et al., 2009; Goldberg et al. 2009; Krueger & South, 2009). We hope that our findings will contribute to an integrated understanding of the relations between clinical disorders and personality disorders and point to directions for the search of etiological processes shared among different disorders as well as for classification of psychopathology.

Acknowledgments

The work for this study was supported by Grant MH-068643 from the National Institutes of Health. The twin program of research at the Norwe-gian Institute of Public Health is supported by grants from The Norwegian Research Council, The Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation, and the European Commission under the program “Quality of Life and Management of the Living Resources” of 5th Framework Program (No. QLG2-CT-2002-01254). We are very thankful to the twins for their participation.

Contributor Information

Espen Røysamb, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, and Department of Psychology, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway.

Kristian Tambs, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway.

Ragnhild E. Ørstavik, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway

Svenn Torgersen, Department of Psychology, University of Oslo, and Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Norway.

Kenneth S. Kendler, The Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics and Departments of Psychiatry and Human Genetics Medical College of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University

Michael C. Neale, The Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics and Departments of Psychiatry and Human Genetics Medical College of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University

Steven H. Aggen, The Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics and Departments of Psychiatry and Human Genetics Medical College of Virginia, Virginia Commonwealth University

Ted Reichborn-Kjennerud, Norwegian Institute of Public Health and Institute of Psychiatry, University of Oslo, Norway.

References

- Aggen SH, Neale MC, Røysamb E, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Kendler KS. A psychometric evaluation of the DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria: Age and sex moderation of criterion functioning. Psychological Medicine. 2009;12:1967–1978. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3. Washington, DC: Author; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews G, Goldberg DP, Krueger RF, Carpenter WT, Jr, Hyman SE, Sachdev P, Pine DS. Exploring the feasibility of a meta-structure for DSM–V and ICD–11: Could it improve utility and validity? Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:1993–2000. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2009;16:397–438. doi: 10.1080/10705510903008204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Austin EJ, Deary IJ. The ‘four As’: A common framework for normal and abnormal personality? Personality and Individual Dif ferences. 2000;28:977–995. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00154-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: A structural equation approach. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW. An overview of analytic rotation in exploratory factor analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36:111–150. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3601_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:103–116. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.103.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung CG. Higher-order factors of the Big Five in a multi-informant sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:1138–1151. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digman JM. Higher-order factors of the Big Five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1246–1256. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrett C, Westen D. The structure of Axis II disorders in adolescents: A cluster- and factor-analytic investigation of DSM–IV categories and criteria. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:440–461. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.4.440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT, MacCallum RC, Strahan EJ. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:272–299. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.4.3.272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan E, Blashfield R. Do clinicians see Axis I and Axis II as different kinds of disorders? Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2006;47:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg DP, Krueger RF, Andrews G, Hobbs MJ. Emotional disorders: Cluster 4 of the proposed meta-structure for DSM–V and ICD–11. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:2043–2059. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Skodol AE. Stability and course of personality disorders: The need to consider comorbidities and continuities between Axis I psychiatric disorders and Axis II personality disorders. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2000;71:291–307. doi: 10.1023/A: 1004680122613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JR, Magnus P, Tambs K. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Panel: A description of the sample and program of research. Twin Research. 2002;5:415– 423. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JR, Magnus P, Tambs K. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health twin program of research: An update. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2006;9:858–864. doi: 10.1375/twin.9.6.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Houston K, Haw C, Townsend E, Harriss L. Comorbidity of Axis I and Axis II disorders in patients who attempted suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1494–1500. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayton JC, Allen DG, Scarpello V. Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: A tutorial on parallel analysis. Organizational Research Methods. 2004;7:191–205. doi: 10.1177/1094428104263675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Helgeland MI, Kjelsberg E, Torgersen S. Continuities between emotional and disruptive behavior disorders in adolescence and personality disorders in adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1941–1947. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Neale MC, Myers JM, Prescott CA, Kendler KS. A population-based twin study of the relationship between neuroticism and internalizing disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:857–864. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications. London: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- James LM, Taylor J. Revisiting the structure of mental disorders: Borderline personality disorder and the internalizing/externalizing spectra. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2008;47:361–380. doi: 10.1348/014466508X299691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen M, Karterud S, Pedersen G, Gude T, Falkum E. An investigation of the prototype validity of the borderline DSM–IV construct. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2004;109:289–298. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0447.2003.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Krueger RF, Bouchard TJ, McGue M. The personalities of twins: Just ordinary folks. Twin Research. 2002;5:125–131. doi: 10.1375/1369052022992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Czajkowski N, Røysamb E, Tambs K, Torgersen S, …, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for DSM–IV personality disorders: A multivariate twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2008;65:1438–1446. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Knudsen GP, Røysamb E, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for syndromal and subsyndromal common DSM–IV Axis I and all Axis II disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10030340. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Aggen SH, Tambs K, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. Illicit psychoactive substance use, abuse and dependence in a population-based sample of Norwegian twins. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:955–962. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Czajkowski N, Tambs K, Torgersen S, Aggen SH, Neale MC, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. Dimensional representations of DSM–IV Cluster A personality disorders in a population-based sample of Norwegian twins: A multivariate study. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1583–1591. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Davis CG, Kessler RC. The familial aggregation of common psychiatric and substance use disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey: A family history study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170:541–548. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.6.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA. Genes, environment, and psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Prescott CA, Myers J, Neale MC. The structure of genetic and environmental risk factors for common psychiatric and substance use disorders in men and women. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:929–937. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM–IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. Continuity of Axes I and II: Toward a unified model of personality, personality disorders, and clinical disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:233–261. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Chentsova-Dutton YE, Markon KE, Goldberg D, Ormel J. A cross-cultural study of the structure of comorbidity among common psychopathological syndromes in the general health care setting. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:437–447. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.3.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE, Patrick CJ, Benning SD, Kramer MD. Linking antisocial behavior, substance use, and personality: An integrative quantitative model of the adult externalizing spectrum. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:645–666. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.4.645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, South SC. Externalizing disorders: Cluster 5 of the proposed meta-structure for DSM–V and ICD–11. Psychological Medicine. 2009;39:2061–2070. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. American Psychologist. 2009;64:241–256. doi: 10.1037/a0015309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesley WJ, Jang KL. The behavioral genetics of personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:247–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.4.022007.141203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesley WJ, Jang KL, Vernon PA. Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:941–948. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE. Modeling psychopathology structure: A symptom-level analysis of Axis I and II disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:273–288. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markon KE, Krueger RF, Watson D. Delineating the structure of normal and abnormal personality: An integrative hierarchical approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:139–157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Muthén B, Asparouhov T, Ludtke O, Robitzsch A, Morin AJS, Trautwein U. Exploratory structural equation modeling, integrating CFA and EFA: Application to students’ evaluations of university teaching. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2009;16:439–476. doi: 10.1080/10705510903008220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder RT, Joyce PR. Temperament and the structure of personality disorder symptoms. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:99–106. doi: 10.1017/S0033291796004114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 4. Los Angeles CA: Muthén Muthén; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham JM. Personality disorders. Focus. 2005;3:372–382.

- Oldham JM, Skodol AE, Kellman H, Hyler SE, Doidge N, Rosnick L, Gallaher GE. Comorbidity of Axis I and Axis II disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:571–578. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orstavik RE, Kendler KS, Czajkowski N, Tambs K, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. The relationship between depressive personality disorder and major depressive disorder: A population-based twin study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1866–1872. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010045. quiz: 1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris J. The nature of borderline personality disorder: Multiple dimensions, multiple symptoms, but one category. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2007;21:457–473. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2007.21.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl BB, Zimmerman M. Structured Interview for DSM–IV Personality (SIDP–IV) Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa, Department of Psychiatry; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Czajkowski N, Neale MC, Ørstavik RE, Torgersen S, Tambs K, Røysamb E, Harris JR, Kendler KS. Genetic and environmental influences on dimensional representations of DSM–IV Cluster C personality disorders: A population-based multivariate twin study. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:645–653. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Czajkowski N, Torgersen S, Neale MC, Orstavik RE, Tambs K, Kendler KS. The relationship between avoidant personality disorder and social phobia: A population-based twin study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1722–1728. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Chambless DL, Renneberg B, Fydrich T. The factor structure of the DSM–III–R personality disorders: An evaluation of competing models. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2005;14:43–55. doi: 10.1002/mpr.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruocco AC. Reevaluating the distinction between Axis I and Axis II disorders: The case of borderline personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61:1509–1523. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanislow CA, Grilo CM, Morey LC, Bender DS, Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Shea MT, McGlashan TH. Confirmatory factor analysis of DSM–IV criteria for borderline personality disorder: Findings from the collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:284–290. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulsman LM, Page AC. The five-factor model and personality disorder empirical literature: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;23:1055–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea MT, Yen S. Stability as a distinction between Axis I and Axis II disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2003;17:373–386. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.5.373.22973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea MT, Stout RL, Yen S, Pagano ME, Skodol AE, Morey LC, Gunderson JG, McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, Bender DS, Zanarini MC. Associations in the course of personality disorders and Axis I disorders over time. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:499 –508. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets E, Craighead WE. Toward an empirically based classification of personality pathology. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2007;14:77–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2007.00065.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA, Livesley WJ, Siever LJ. The borderline diagnosis I: Psychopathology, comorbidity, and personality structure. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:936–950. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(02)01324-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade T. The descriptive epidemiology of internalizing and externalizing psychiatric dimensions. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2007;42:554–560. doi: 10.1007/s00127-007-0200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade T, Watson D. The structure of common DSM–IV and ICD–10 mental disorders in the Australian general population. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:1593–1600. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambs K, Moum T. How well can a few questionnaire items indicate anxiety and depression? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1993;87:364–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambs K, Ronning T, Prescott CA, Kendler KS, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Torgersen S, Harris JR. The Norwegian Institute of Public Health Twin Study of Mental Health: Examining recruitment and attrition bias. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2009;12:158–168. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.2.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torgersen S, Kringlen E, Cramer V. The prevalence of personality disorders in a community sample. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:590–596. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Durrett CA. Categorical and dimensional models of personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:355–380. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Sher KJ. Relationship between the five-factor model of personality and Axis I disorders in a nonclinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:350–360. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.103.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: A quantitative hierarchical model for DSM–V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:522–536. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Chmielewski M. Structures of personality and their relevance to psychopathology: II. Further articulation of a comprehensive unified trait structure. Journal of Personality. 2008;76:1545–1586. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CN, Gunderson JG, Zanarini MC, Hudson JI. Family studies of borderline personality disorder: A review. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2003;11:8–19. doi: 10.1080/10673220303937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA. Personality disorder and Axis I psychopathology: The problematic boundary of Axis I and Axis II. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2003;17:90–108. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.2.90.23987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Mullins-Sweatt SN. Five-factor model of personality disorder: A proposal for DSM–V. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5:197–220. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widiger TA, Simonsen E, Krueger R, Livesley WJ, Verheul R. Personality disorder research agenda for the DSM–V. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2005;19:315–338. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2005.19.3.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO–Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): A critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1994;28:57– 84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Pfister H. DIA–X interviews (M–CIDI) Frankfurt, Germany: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Bagby RM, Costa PT, Jr, Ryder AG, Herbst JH. Assessing the DSM–IV structure of personality disorder with a sample of Chinese psychiatric patients. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2002;16:317–331. doi: 10.1521/pedi.16.4.317.24127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]