Abstract

M phase phosphoprotein 8 (MPP8) harbors a N-terminal chromodomain and a C-terminal ankyrin repeat domain. MPP8, via its chromodomain, binds histone H3 peptide tri- or di-methylated at lysine 9 (H3K9me3/2) in submicromolar affinity. We determined the crystal structure of MPP8 chromodomain in complex with H3K9me3 peptide. MPP8 interacts with at least six histone H3 residues from glutamine 5 to serine 10, enabling its ability to distinguish lysine 9 containing peptide (QTARKS) from that of lysine 27 (KAARKS), both sharing the ARKS sequence. A partial hydrophobic cage with three aromatic residues (Phe59, Trp80, Tyr83) and one aspartate (Asp87) encloses the methylated lysine 9. MPP8 has been reported to be phosphorylated in vivo, including the cage residue Tyr83 and the succeeding Thr84 and Ser85. Modeling a phosphate group onto the side chain hydroxyl oxygen of Tyr83 suggests the negatively charged phosphate group could enhance the binding of positively charged methyl-lysine or create a regulatory signal by allowing or inhibiting binding of other protein(s).

Keywords: X-ray crystallography, epigenetics, MPP8 phosphorylation, methyl-lysine binding

The M phase phosphoprotein 8 (MPP8) was initially identified by expression cloning 1; with its gene located on human chromosome 13q12 2. MPP8 had been initially characterized in association with a Ran, Ras-like nuclear small GTPase 3 and a neuroprotective peptide 4 by the two-hybrid analyses. Recently, MPP8 has been shown to interact with histone H3 methylated at lysine 9 (H3K9me1/2/3) - a modification associated with transcriptional repression – via its N-terminal chromodomain (Fig. 1a) 5; 6. This binding event of MPP8-H3K9me modulates the expression of E-cadherin, a key regulator of cell-cell adhesion with implications in embryonic development, tissue morphogenesis and homeostasis 7, together with H3K9 methyltransferases GLP (G9a-like protein) and ESET (also known as SETDB1) and DNA methyltransferase 3a (Dnmt3a) 6. Both GLP (and associated G9a) and SETDB1 are euchromatic histone enzymes, generating H3K9me1 and H3K9me2 (by G9a/GLP 8) and H3K9me3 (by SETDB1 9), respectively. In addition, many phosphorylation sites on MPP8 have been identified including one tyrosine, one threonine and one serine in a consecutive sequence within the chromodomain 10 (Fig. 1b). Here, we describe the structure of human MPP8 chromodomain in complex with H3 peptide (residues 1–15) with lysine 9 trimethylated, examine the potential effect of phosphorylation on methyl-lysine binding and compare its interaction of H3K9me3 with that of classical HP1 (heterochromatin protein 1) chromodomain 11.

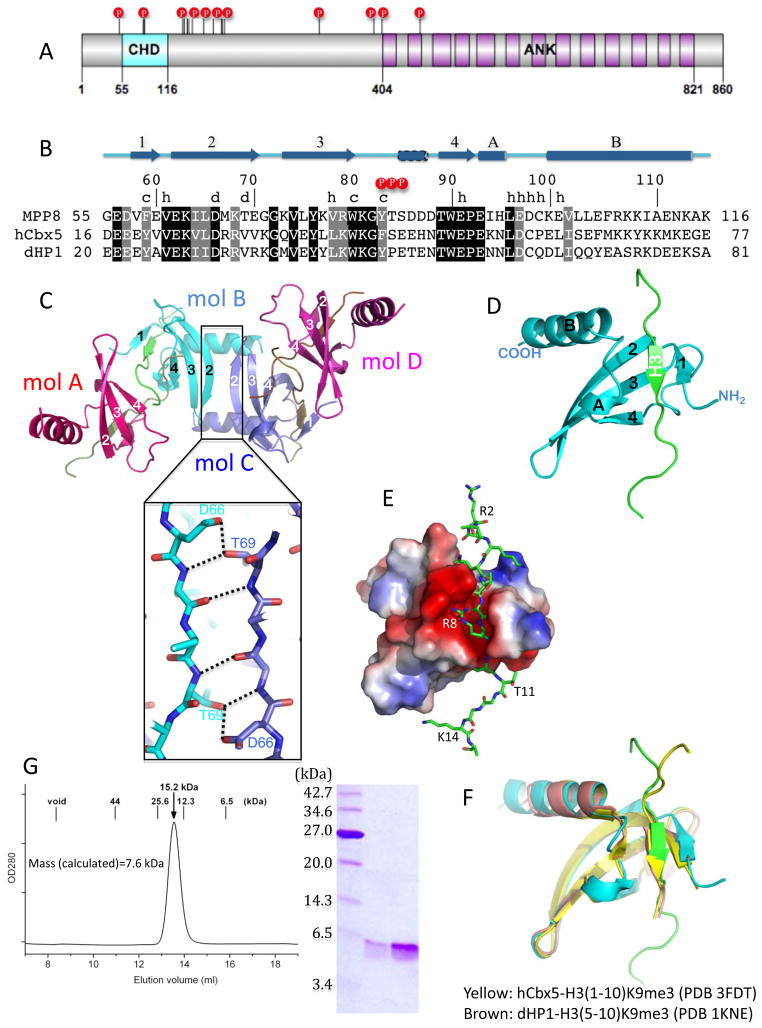

Figure 1. Overall structure of MPP8 chromodomain.

(a) Schematic representation of human MPP8. Letters P indicates the phosphorylation sites 10. The number of ankyrin repeats (ANK) is assigned based on the secondary structure prediction 31 (see Supplementary Fig. S3).

(b) Sequence alignment of chromodomains of human MPP8, human HP1 (also known as Cbx5) and Drosophila HP1. Secondary structural elements (arrows for beta strands, and rectangles for alpha helices) are indicated. A small 310 helix (a dashed rectangle) between strands β3 and β4 is recognized in molecule C, whereas helical features exist in the corresponding regions in molecules A, B and D (see panel c). White-on-black residues are invariant among the three sequences examined, while gray-highlighted positions are conserved (R and K, E and D, T and S, Q and N, F and Y, V, I, L and M). Positions highlighted are responsible for various functions as indicated (P=phosphorylation sites, c=cage forming residues, h=histone H3 peptide interaction, d=dimer formation).

(c) The crystallographic asymmetric unit contains four complexes of MPP8 chromodomain-H3 peptide (molecules A–D). The dimer interface (B–C) is formed by strand β2 through an antiparallel arrangement (insert). Molecule A (or D) forms the same dimer with the crystallographic symmetry-related molecule A (or D). The same dimer is formed in the apo-structure 14 (Supplementary Fig. S2b). The C-terminal residues of the bound histone H3 peptide mediates the A–B and C–D interfaces (Supplementary Fig S2a).

(d) Monomer structure of MPP8 chromodomain (cyan) bound with a cognate histone H3 peptide (green).

(e) Surface representation of MPP8 chromodomain displayed as blue for positive, red for negative and white for neutral. The bound H3 peptide is shown as a stick model.

(f) Superimposition of MPP8 (cyan), human HP1 (yellow) 13 and Drosophila HP1 (brown) 11 by their respective chromodomains. The pair-wise rmsd between MPP8 and human or Drosophila HP1 is ~0.6 Å (200 pairs of main chain atoms) or 0.9 Å (204 pairs of main chain atoms), respectively.

(g) Elution profile of MPP8 chromodomain on a Superdex 75 (10/300 GL) (GE Healthcare). The column buffer was 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM dithiothreitol, and the protein concentration was 3 mg ml−1 in 200 μl. The insert is a 17% SDS with the size of the molecular weight marker indicated.

Overall structure of MPP8 chromodomain-H3 peptide complex

The human MPP8 chromodomain (residues 55–116) was overexpressed as an N-terminal His6-SUMO fusion protein in Escherichia coli 12. Crystals of the tag removed MPP8 chromodomain in complex with H3(1–15)K9me3 formed in the P43212 space group (Supplementary Fig. S1). The structure was determined at the resolution of 2.5 Å (Supplementary Table 1). The crystallographic asymmetric unit contains four complexes (Fig. 1c). The monomeric structures are highly similar with each other, with a root mean squared deviation (rmsd) of approximately 0.5 Å when pair-wise comparing 228 pairs of main-chain atoms.

The monomeric structure of MPP8 chromodomain is composed of a N-terminal SH3-like β-barrel, followed by short 310 helix (αA) and a C-terminal long helix (αB) (Fig. 1d). The N-terminal β-barrel structure consists of a sheet with three antiparallel strands (β2–β4), packed with a two-stranded sheet formed by β1 and the histone peptide. The histone peptide is inserted antiparallelly between strand β1 and the loop between helices αA and αB, in an acidic cleft of the chromodomain (Fig. 1e). The structure of MPP8 chromodomain is highly similar to that of the human and Drosophila HP1 chromodomain structures 11; 13 (Fig. 1f), with approximately 30% sequence identities scattered throughout the entire β-barrel region while the C-terminal helix αB varies in sequence (Fig. 1b).

Each monomer has two conserved inter-molecular interactions with its neighboring molecules: one involves the edge strand β2 in an antiparallel arrangement (Fig. 1c), and the other is mediated by the C-terminal residues of the bound histone peptide (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S2a). The antiparallel inter-molecular β2-β2 interaction, also observed in the absence of bound histone peptide 14 (Supplementary Fig. S2b), involves side chain interactions of Asp66 of one molecule and Thr69 of the other (Fig. 1c, insert). Thr69 is unique to MPP8 (Fig. 1b; three-letter code for MPP8 residues). Analytic gel filtration measurement suggests the protein exists as dimer in solution (Fig. 1g).

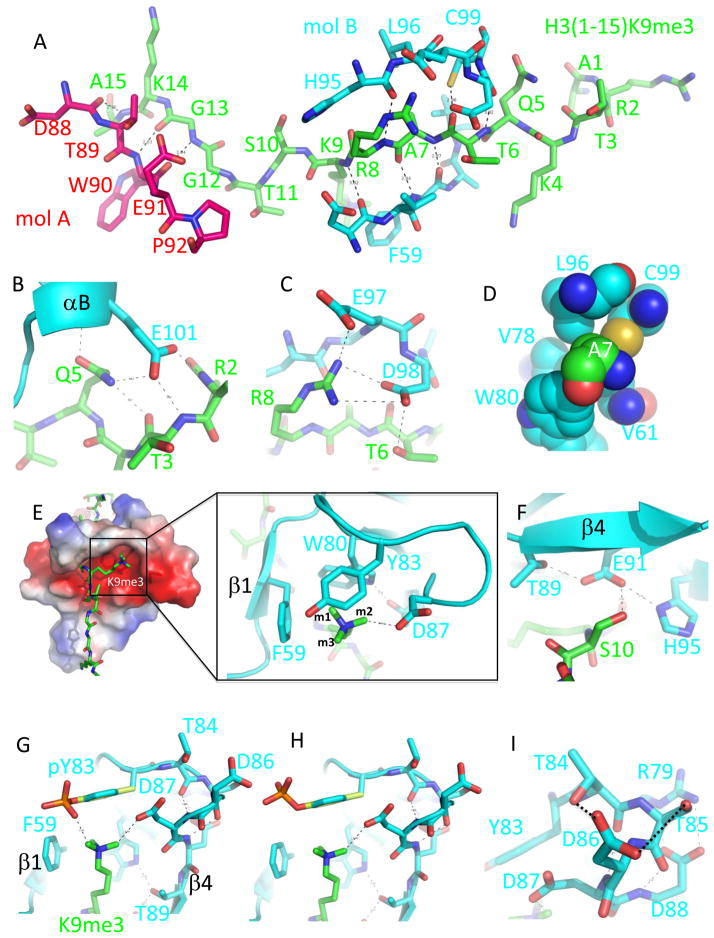

Figure 2. MPP8 chromodomain-H3 interactions.

(a) Stick model showing the H3 peptide (green), residues A1–A15. The cognate chromodomain (molecule B in cyan) contacts the first 10 residues of the H3 peptide, but H3 residues 11–15 interact with a neighbouring chromodomain (molecule A in red).

(b) H3Q5 is recognized by Glu101 of N-terminal end of helix αB.

(c) H3T6 and H3R8 interactions with two acidic amino acids, Glu97 and Asp98.

(d) The hydrophobic pocket for H3A7. The atoms are colored as red for oxygen, blue for nitrogen, cyan (MPP8) or green (H3) for carbon atoms.

(e) H3K9me3 binding in the cage. One of its terminal N-CH3 groups (m1) projects toward the three aromatic rings, the second methyl group (m2) points toward Asp87, forming a hydrogen bond of C-H…O type - a type of hydrogen bond that occurs in the active sites of both SET and jumonji domains 32; 33. The third methyl group (m3) points to open side of the cage.

(f) H3S10 interacts with the side chain of Glu91, which in turn interacts with His95 and Thr89. The side-chain hydroxyl oxygen of Thr89 forms an additional intra-molecule hydrogen bond with Trp80, one of the cage residues (see Fig. 3).

(g) The model of phosphated-Tyr83 with the phosphate group potentially interacting with one of the terminal N-CH3 groups.

(h) The phosphate group of phosphorylated Tyr83 could point toward to the solvent by allowing or inhibiting binding of specific regulatory proteins.

(i) A network of polar interactions involving Thr84-Asp86-Ser85.

Substrate specificity of H3K9 peptide binding by MPP8

All fifteen residues of the H3 peptide, in an extended conformation, were observed. The first 10 residues of the H3 peptide binds to one chromodomain, but H3 residues 11 to 15 interact with a neighboring chromodomain molecule (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S2a). The surface area buried at the cognate MPP8-peptide interface is approximately 700 Å2, with these extensive intermolecular interactions. (1) The main chain amide nitrogen atoms of H3R2-H3T3 form hydrogen bonds with the side chain carboxyl oxygen atoms of Glu101 of helix αB (Fig. 2b). (2) H3Q5–H3K9 forms backbone hydrogen bonds with strand β1 (including Phe59) on one side, and on the other side, His95 of helix αA and the following loop (Fig. 2a). (3) The main chain carbonyl oxygen atom of H3T6 forms a hydrogen bond with the sulfur atom of Cys99 (Fig. 2a), the residue proceeding to helix αB.

The substrate specificity of the MPP8 chromodomain is determined primarily through the recognition of histone residues of H3Q5-H3S10. The side chain of H3Q5 sits in the amino end of helix αB, forming hydrogen bonds with both the main-chain amide nitrogen atom and the side-chain carboxyl atom of Glu101, as well as an intra-molecular hydrogen bond with main-chain carbonyl oxygen atom of H3T3 (Fig. 2b). The hydroxyl group of H3T6 forms a hydrogen bond with Asp98 (Fig. 2c). The side chain of H3A7 inserts into a shallow hydrophobic pocket formed by Val61, Val78, Trp80, Leu96 and Cys99 (Fig. 2d). The side chain of H3R8 interacts with Glu97 and Asp98 (Fig. 2c). H3K9me3 is bound in a partial hydrophobic and open cage formed by three aromatic residues (Phe59, Trp80, Tyr83) and one acidic residue (Asp87) (Fig. 2e). Mutation of Trp80 to alanine (W80A) abrogates binding to H3K9 methylated peptide 6. One methyl group (m1) of H3K9me3 points toward to all three aromatic residues, the second methyl group (m2) bridges to acidic Asp87, while the third methyl group (m3) points to solvent. It is common to have a glutamate or aspartate residue in (or near) the methyl-lysine binding cage 15. The H3 peptide-binding site is further defined by H3S10, whose side-chain hydroxyl oxygen forms a hydrogen bond with Glu91 of strand β4 (Fig. 2f).

We believe the extensive interaction between MPP8 and the six histone H3 residues, particularly H3Q5 and H3T6, is the reason that MPP8 is able to distinguish K9 peptide (QTARKS) from that of K27 (KAARKS), both of which share the ARKS sequence, yet MPP8 displayed no binding to H3 peptide containing K27 methylated or unmethylated 6.

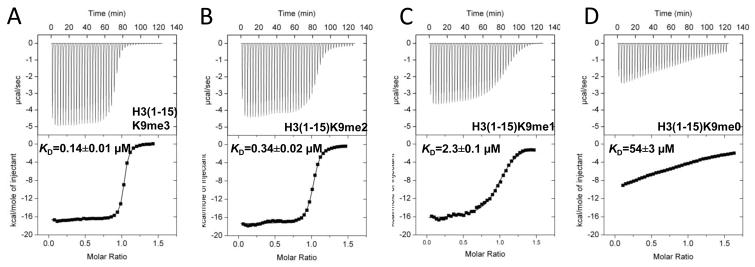

Consistent with this notion is the observation that residues Glu97, Asp98, Cys99, and Glu101 (located in the loop between helices αA and αB and the N-terminal end of helix αB) are not conserved between MPP8 and HP1 (Fig. 1b). These residues contribute to the recognition of H3Q5 (via Glu101), T6 (Asp98), A7 (Cys99), R8 (Glu97 and Asp98), and overall binding affinity of H3 peptide. MPP8 chromadomain binds H3K9-tri (me3) or di-methylated (me2) H3 peptide in submicromolar affinity, with a KD of approximately 0.14 or 0.34 μM, respectively, measured by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) (Fig. 3a–b). The peptide carrying a single methyl group (H3K9me1) resulted in a KD value of 2.3 μM (a reduction by a factor of approximately 7 from that of H3K9me2) (Fig. 3c), and the KD for unmethylated peptide (H3K9me0) further increased by a factor of 23 to approximately 54 μM (Fig. 3d). Consistent with the pulldown results 6, MPP8 chromodomain is capable of binding to methyl-H3K9 peptide regardless of degree of methylation. Even for the unmethylated form, the binding affinity can be measured quantitatively. Although the absolute KD values differs significantly between MPP8-H3K9me3 (0.14 μM) and HP1-H3K9me3 (10 μM) 16, their abilities to discriminate various degrees of methylation are similar: each methyl group decrease from me3 to me0 results in an increase of KD by a factor of 2.4, 7 and 23 for MPP8 and 1.5, 6.4 and >10 for HP1.

Figure 3. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) measurement.

Binding of MPP8 chromodomain to H3(1–15) peptides with varying degree of methylation of lysine 9 (me3-0) was carried out under the conditions of 150 μM protein concentration and 0.9–1.2 mM peptide concentration in 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP), using the MicroCal VP-ITC instrument at 25 °C. Binding constant was calculated by fitting the data to one-site binding model equation using the ITC data-analysis module of Origin 7.0 (OriginLab Corporation). KD values are shown.

Hypothetical model of phosphorylation effect on methyl-lysine binding

It is interesting to note that one of the three phosphorylation sites (Tyr83, Thr84 and Ser85) within the MPP8 chromodomain 10 is directly involved in methyl-lysine cage formation (Fig. 2e). To investigate the effect of Tyr83 phosphorylation, we modeled a phosphate group to the side chain hydroxyl oxygen of Tyr83. Without affecting the cage formation, the torsional rotation of its side chain C-O bond would position the negatively charged phospho group in the open end of the cage near the positively charged tri-methyl-amino group (Fig. 2g), forming a favorable interaction and thus enhancing the methyl-lysine binding. Alternatively, the phosphate group could be positioned away from protein and histone atoms and point toward the solvent (Fig. 2h), thus creating a signal for other phosphorylation dependent protein-protein recognition.

The side-chain hydroxyl groups of Thr84 and Ser85 interact with the side-chain carboxyl group of the succeeding Asp86, which is followed by Asp87 that interacts with the methyl-lysine (Fig. 2e) and Asp88 that forms an intra-molecular salt bridge with Arg79 (Fig. 2i). Phosphorylation of either or both Thr84 and Ser85 would require the side chains to take different rotomer conformations to position the phosphate groups away from Asp86. Otherwise steric clashes will occur and result in the repulsion of Asp86, and thus affect the preceding Tyr83 or succeeding Asp87 in their interactions with the methyl-lysine.

Discussion

Multiple interdependent post-translational modifications of cellular proteins allow for combinatorial readout. Some of these modifications, including phosphorylation and methylation, might participate in cross-talk for dynamic control of cellular signaling under various physiological conditions 17. Protein phosphorylation is involved in various cellular processes via cellular signaling pathways. Protein methylation, especially on lysines, is another important post-translational modification of cellular proteins. For example, histone methylation is involved in the regulation of transcription 18. Combinations of these modifications on histones (such as histone H3K9 methylation and H3S10 phosphorylation 19; 20 cooperate to regulate chromatin structure and transcription by allowing or inhibiting binding of specific regulatory proteins. Similarly, non-histone proteins such as p53 21; 22, estrogen receptor 23, DNMT1 24 and NF-κB 25 are also regulated by post-translational modifications, and in some examples, by an methylation and phosphorylation switch between adjacent lysine and serine residues. Here we suggest the phosphorylation of MPP8 might influence its binding of methylated H3K9. The identification of protein kinase(s) and phosphatase(s) involved in MPP8 phosphorylation will be essential for further study. We note that recent studies suggested that multiply phosphorylations at N-terminal serine residues (Ser11-Ser14) in mammalian HP1α enhanced its affinity for H3K9me 26, whereas phosphorylation of Ser42 of mouse Cbx2 within its chromodomain (equivalent to Thr89 of MPP8) resulted in a reduced level of binding to an H3 peptide 27.

We do not know the functional significance of dimer formation of MPP8 chromodomain. It should be noted that the intact protein of MPP8 may or may not be a dimer. HP1 dimerizes via its C-terminal chromo shadow domain 28. It is intriguing to note that two proteins (GLP and Dnmt3a) involved in MPP8-mediated E-cadherin gene silencing 6 are dimers as well. G9a and GLP form heterodimers in corepressor complexes, and the heterodimer formation requires their C-terminal sequences encompassing the catalytic SET domains 29. Dnmt3a dimerizes via its C-terminal catalytic domain 30. This dimer formation could simply be because the binding substrate of these chromatin interacting proteins, the nucleosome, contains a dimer of H3, which requires the simultaneous recognition of two histone H3 molecules.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants GM068680 to X.C. from the US National Institutes of Health. X.C. is a Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar. M.T.B. is supported by NIH grant number DK62248 and, in part, by institutional grant NIEHS ES07784. The X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) on the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamline APS-24-ID-E, which is supported by award RR-15301 from the National Center for Research Resources at the National Institutes of Health. Use of the APS is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Footnotes

PDB accession number

The coordinates and structure factors of MPP8 chromodomain-H3 peptide complex have been deposited with the accession number 3QO2.

Author Contributions

Y.C. performed protein purifications, ITC measurements, crystallization, and participated in X-ray data collection; J.R.H. collected X-ray data, determined structures and performed structural refinements; M.T.B. provided initial expression construct; X.Z. and X.C. organized and designed the scope of the study; X.C. wrote the manuscript; all were involved in analyzing data and helped in revising the manuscript.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Matsumoto-Taniura N, Pirollet F, Monroe R, Gerace L, Westendorf JM. Identification of novel M phase phosphoproteins by expression cloning. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1455–69. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.9.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunham A, Matthews LH, Burton J, Ashurst JL, Howe KL, Ashcroft KJ, Beare DM, Burford DC, Hunt SE, Griffiths-Jones S, Jones MC, Keenan SJ, Oliver K, Scott CE, Ainscough R, Almeida JP, Ambrose KD, Andrews DT, Ashwell RI, Babbage AK, Bagguley CL, Bailey J, Bannerjee R, Barlow KF, Bates K, Beasley H, Bird CP, Bray-Allen S, Brown AJ, Brown JY, Burrill W, Carder C, Carter NP, Chapman JC, Clamp ME, Clark SY, Clarke G, Clee CM, Clegg SC, Cobley V, Collins JE, Corby N, Coville GJ, Deloukas P, Dhami P, Dunham I, Dunn M, Earthrowl ME, Ellington AG, Faulkner L, Frankish AG, Frankland J, French L, Garner P, Garnett J, Gilbert JG, Gilson CJ, Ghori J, Grafham DV, Gribble SM, Griffiths C, Hall RE, Hammond S, Harley JL, Hart EA, Heath PD, Howden PJ, Huckle EJ, Hunt PJ, Hunt AR, Johnson C, Johnson D, Kay M, Kimberley AM, King A, Laird GK, Langford CJ, Lawlor S, Leongamornlert DA, Lloyd DM, Lloyd C, Loveland JE, Lovell J, Martin S, Mashreghi-Mohammadi M, McLaren SJ, McMurray A, Milne S, Moore MJ, Nickerson T, Palmer SA, Pearce AV, Peck AI, Pelan S, Phillimore B, Porter KM, Rice CM, Searle S, Sehra HK, Shownkeen R, et al. The DNA sequence and analysis of human chromosome 13. Nature. 2004;428:522–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umeda M, Nishitani H, Nishimoto T. A novel nuclear protein, Twa1, and Muskelin comprise a complex with RanBPM. Gene. 2003;303:47–54. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maksimov VV, Arman IP, Tarantul VZ. Identification of the proteins interacting with neuroprotective peptide humanin in a yeast two-hybrid system. Genetika. 2006;42:274–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bua DJ, Kuo AJ, Cheung P, Liu CL, Migliori V, Espejo A, Casadio F, Bassi C, Amati B, Bedford MT, Guccione E, Gozani O. Epigenome microarray platform for proteome-wide dissection of chromatin-signaling networks. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kokura K, Sun L, Bedford MT, Fang J. Methyl-H3K9-binding protein MPP8 mediates E-cadherin gene silencing and promotes tumour cell motility and invasion. Embo J. 2010;29:3673–87. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Roy F, Berx G. The cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:3756–88. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8281-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tachibana M, Sugimoto K, Nozaki M, Ueda J, Ohta T, Ohki M, Fukuda M, Takeda N, Niida H, Kato H, Shinkai Y. G9a histone methyltransferase plays a dominant role in euchromatic histone H3 lysine 9 methylation and is essential for early embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1779–91. doi: 10.1101/gad.989402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang H, An W, Cao R, Xia L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Chatton B, Tempst P, Roeder RG, Zhang Y. mAM facilitates conversion by ESET of dimethyl to trimethyl lysine 9 of histone H3 to cause transcriptional repression. Mol Cell. 2003;12:475–87. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen JV, Blagoev B, Gnad F, Macek B, Kumar C, Mortensen P, Mann M. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobs SA, Khorasanizadeh S. Structure of HP1 chromodomain bound to a lysine 9-methylated histone H3 tail. Science. 2002;295:2080–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1069473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lan F, Collins RE, De Cegli R, Alpatov R, Horton JR, Shi X, Gozani O, Cheng X, Shi Y. Recognition of unmethylated histone H3 lysine 4 links BHC80 to LSD1-mediated gene repression. Nature. 2007;448:718–22. doi: 10.1038/nature06034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravichandran M, Amaya MF, Loppnau P, Kozieradzki I, Edwards AM, Arrowsmith CH, Weigelt J, Bountra C, Bochkarev A, Min J, Ouyang H. Crystal structure of the complex of human chromobox homolog 5 (CBX5) with H3K9(me)3 peptide. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Z, Pan P, MacKenzie F, Crombet L, Bountra C, Weigelt J, Arrowsmith CH, Edwards AM, Bochkarev A, Min J. The crystal structure of MPP8. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brent MM, Marmorstein R. Ankyrin for methylated lysines. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:221–2. doi: 10.1038/nsmb0308-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes RM, Wiggins KR, Khorasanizadeh S, Waters ML. Recognition of trimethyllysine by a chromodomain is not driven by the hydrophobic effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11184–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610850104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–5. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007;447:407–12. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rea S, Eisenhaber F, O’Carroll D, Strahl BD, Sun ZW, Schmid M, Opravil S, Mechtler K, Ponting CP, Allis CD, Jenuwein T. Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature. 2000;406:593–9. doi: 10.1038/35020506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischle W, Wang Y, Allis CD. Binary switches and modification cassettes in histone biology and beyond. Nature. 2003;425:475–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chuikov S, Kurash JK, Wilson JR, Xiao B, Justin N, Ivanov GS, McKinney K, Tempst P, Prives C, Gamblin SJ, Barlev NA, Reinberg D. Regulation of p53 activity through lysine methylation. Nature. 2004;432:353–60. doi: 10.1038/nature03117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang J, Sengupta R, Espejo AB, Lee MG, Dorsey JA, Richter M, Opravil S, Shiekhattar R, Bedford MT, Jenuwein T, Berger SL. p53 is regulated by the lysine demethylase LSD1. Nature. 2007;449:105–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subramanian K, Jia D, Kapoor-Vazirani P, Powell DR, Collins RE, Sharma D, Peng J, Cheng X, Vertino PM. Regulation of estrogen receptor alpha by the SET7 lysine methyltransferase. Mol Cell. 2008;30:336–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esteve PO, Chang Y, Samaranayake M, Upadhyay AK, Horton JR, Feehery GR, Cheng X, Pradhan S. A methylation and phosphorylation switch between an adjacent lysine and serine determines human DNMT1 stability. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:42–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy D, Kuo AJ, Chang Y, Schaefer U, Kitson C, Cheung P, Espejo A, Zee BM, Liu CL, Tangsombatvisit S, Tennen RI, Kuo AY, Tanjing S, Cheung R, Chua KF, Utz PJ, Shi X, Prinjha RK, Lee K, Garcia BA, Bedford MT, Tarakhovsky A, Cheng X, Gozani O. Lysine methylation of the NF-kappaB subunit RelA by SETD6 couples activity of the histone methyltransferase GLP at chromatin to tonic repression of NF-kappaB signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:29–36. doi: 10.1038/ni.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiragami-Hamada K, Shinmyozu K, Hamada D, Tatsu Y, Uegaki K, Fujiwara S, Nakayama J. N-Terminal Phosphorylation of HP1{alpha} Promotes Its Chromatin Binding. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1186–200. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01012-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatano A, Matsumoto M, Higashinakagawa T, Nakayama KI. Phosphorylation of the chromodomain changes the binding specificity of Cbx2 for methylated histone H3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;397:93–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thiru A, Nietlispach D, Mott HR, Okuwaki M, Lyon D, Nielsen PR, Hirshberg M, Verreault A, Murzina NV, Laue ED. Structural basis of HP1/PXVXL motif peptide interactions and HP1 localisation to heterochromatin. Embo J. 2004;23:489–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tachibana M, Ueda J, Fukuda M, Takeda N, Ohta T, Iwanari H, Sakihama T, Kodama T, Hamakubo T, Shinkai Y. Histone methyltransferases G9a and GLP form heteromeric complexes and are both crucial for methylation of euchromatin at H3-K9. Genes Dev. 2005;19:815–26. doi: 10.1101/gad.1284005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia D, Jurkowska RZ, Zhang X, Jeltsch A, Cheng X. Structure of Dnmt3a bound to Dnmt3L suggests a model for de novo DNA methylation. Nature. 2007;449:248–251. doi: 10.1038/nature06146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bryson K, McGuffin LJ, Marsden RL, Ward JJ, Sodhi JS, Jones DT. Protein structure prediction servers at University College London. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W36–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Couture JF, Hauk G, Thompson MJ, Blackburn GM, Trievel RC. Catalytic roles for carbon-oxygen hydrogen bonding in SET domain lysine methyltransferases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19280–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602257200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horton JR, Upadhyay AK, Qi HH, Zhang X, Shi Y, Cheng X. Enzymatic and structural insights for substrate specificity of a family of jumonji histone lysine demethylases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:38–43. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.