Abstract

Antagonism of prepulse inhibition (PPI) deficits produced by psychotomimetic drugs has been widely used as an effective tool for the study of the mechanisms of antipsychotic action and identifying potential antipsychotic drugs. Many studies have relied on the acute effect of a single administration of antipsychotics, whereas patients with schizophrenia are treated chronically with antipsychotic drugs. The clinical relevance of acute antipsychotic effect in this model is still an open question. In this study, we investigated the time course of repeated antipsychotic treatment on persistent PPI deficit induced by repeated phencyclidine (PCP) treatment. After a baseline test with saline, male Sprague-Dawley rats were repeatedly injected with either vehicle, haloperidol (0.05 mg/kg), clozapine (5.0 or 10.0 mg/kg), olanzapine (2.0 mg/kg), risperidone (1.0 mg/kg) or quetiapine (10 mg/kg), followed by PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc) and tested for PPI once daily for 6 consecutive days. A single injection of PCP disrupted PPI and this effect was maintained with repeated PCP injections throughout the testing period. Acute clozapine, but not other antipsychotic drugs, attenuated acute PCP-induced PPI disruption at both tested doses. With repeated treatment, clozapine and quetiapine maintained their attenuation, while risperidone enhanced its effect with a significant reduction of PCP-induced disruption toward the end of treatment period. In contrast, repeated haloperidol and olanzapine treatments were ineffective. The PPI effects of these drugs were more conspicuous at a higher prepulse level (e.g. 82 dB) and were dissociable from their effects on startle response and general activity. Overall, the repeated PCP-PPI model appears to be a useful model for the study of the time-dependent antipsychotic effect, and may help identify potential treatments that have a quicker onset of action than current antipsychotics.

Keywords: prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle, repeated phencyclidine treatment, haloperidol, clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine

Introduction

Prepulse inhibition (PPI) of acoustic startle response is a paradigm commonly used to assess sensorimotor gating, a preattentive ability which is impaired in patients with schizophrenia and in animals acutely treated with dopamine agonists and NMDA antagonists. This paradigm is thought to possess face, construct, and predictive validity for the information processing deficits observed in patients with schizophrenia (Geyer et al. 1990; Swerdlow et al. 1994). Besides its popularity in the field of animal models of schizophrenia, it has also been successfully used to screen chemical compounds with potential antipsychotic activity (Geyer et al., 2001, Swerdlow et al., 1991), to rank order clinical potency of approved antipsychotics (Swerdlow et al., 2008), and to differentiate atypical from typical antipsychotics (Geyer and Ellenbroek, 2003). For example, antagonism of acute apomorphine-induced disruption of PPI is shown to be a reliable and sensitive screening test for antipsychotic activity (Rigdon and Viik, 1991, Swerdlow and Geyer, 1993), and acute NMDA antagonists PPI models are found to be effective in differentiating atypical from typical antipsychotics to some extent (Geyer and Ellenbroek, 2003).

One of the lingering issues associated with many antipsychotic PPI studies is the clinical relevance of acute effect of antipsychotic treatment on deficient PPIs. Because antipsychotic treatments in patients with schizophrenia are administered repeatedly and chronically, the extent to which the acute effect of antipsychotic treatment in various PPI models reflects the clinically relevant action against psychosis or cognitive deficits remains unclear. In recent years, several clinical reports suggest that antipsychotic action starts early and increases in magnitude with repeated treatment (Agid et al., 2003, Agid et al., 2006, Emsley et al., 2006, Glick et al., 2006, Kapur et al., 2005, Leucht et al., 2005, Raedler et al., 2007). An animal model based on the PPI paradigm that faithfully captures this time course of action is still lacking. Previous work on the effects of repeated antipsychotic treatment on deficient PPIs is rather limited. Some have examined the treatment effects after a certain period of treatment has elapsed (e.g., ~ 21 days after the first drug administration), instead of during the chronic treatment period (Andersen and Pouzet, 2001, Feifel and Priebe, 1999, Rueter et al., 2004). Others have examined the drug effect only at the beginning and end of treatment period (Briody et al., 2010, Feifel et al., 2007), and are thus limited in the ability to track changes that have occurred during the treatment period. To the best of our knowledge, only two studies have examined the effect of repeated antipsychotic treatment on deficient PPIs during the drug treatment period with positive results (Martinez et al., 2000, Pietraszek and Ossowska, 1998). They both reported that chronic administrations of haloperidol reversed the disruptive effect of PCP on PPI. What is less known is whether repeated administrations of atypical antipsychotics (e.g. clozapine, olanzapine) also exhibit this effect. Because acute treatment of clozapine (Bakshi et al., 1994), olanzapine (Bakshi and Geyer, 1995) or quetiapine (Swerdlow et al., 1996) is immediately effective in reversing or reducing PCP-induced PPI disruption, it would be important to determine how repeated treatment of these drugs would influence PCP-induced PPI disruption. If the reversal effect is maintained or even increased over the treatment period, it would suggest that the PCP PPI model based on repeated antipsychotic treatment regimens may be a valid model to capture the time course of clinically relevant effects of antipsychotic treatment. This model may, in turn, be used to study the underlying neurobiological mechanisms and identify potential treatments that may have quicker onset of action than the currently used antipsychotics.

In the present study, we investigated how repeated administrations of haloperidol, clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine affect PCP-induced PPI disruption. Haloperidol primarily binds to DA D2 receptors, whereas other atypical antipsychotics are high 5-HT2A and low D2 antagonists. Clozapine has high affinities for serotonin 5-HT2A, muscarinic M1 and histamine H1 receptors, moderate affinities for D4, 5-HT2c, α1- adrenergic receptors, and a relatively low affinity for D2. Olanzapine has high affinities for 5-HT2A, M1 and H1 receptors and moderate affinities for D1, D2, D4 and α1 receptors. Risperidone demonstrates high affinities for D2, 5-HT2A and α1- adrenergic receptors, as well as some affinities for D1, D4, α1-adrenergic, and α2- adrenergic receptors. Quetiapine, very much like clozapine, also has high to moderate affinities for α1- adrenergic, 5-HT2A, H1 and low affinities for D1, D2 and α2- adrenergic receptors (Jibson and Tandon, 1998, Miyamoto et al., 2005). We were particularly interested in whether repeated antipsychotic treatment would produce a progressively increased attenuation of PCP-induced PPI deficits. In our previous work, we have demonstrated that repeated antipsychotic treatment in the conditioned avoidance response model and PCP-induced hyperlocomotion model is capable of modeling the time course of antipsychotic effect (Li et al., 2007, Li et al., 2010, Mead and Li, 2010, Sun et al., 2009). Repeated antipsychotic treatment progressively enhances its disruption of avoidance responding and progressively potentiates its inhibition of PCP-induced hyperlocomotion across the drug testing sessions. Because all three models are commonly used to screen antipsychotic activity with high predictive validity, it is of great importance to determine whether PCP-induced PPI deficit model based on repeated antipsychotic treatment regimen would also capture the time course of antipsychotic treatment in the clinic as shown in the other two models.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–275g upon arrival, Charles River, Portage, MI) were housed two per cage, in 48.3 cm × 26.7 cm × 20.3 cm transparent polycarbonate cages under 12-hr light/dark conditions (light on between 6:00am and 6:00pm). Room temperature was maintained at 22±1° with a relative humidity of 55–60%. Food and water was available ad libitum. Animals were allowed at least one week of habituation to the animal facility before being used in experiments. All procedures were approved by the animal care committee at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Prepulse inhibition of acoustic startle reflex apparatus

The prepulse inhibition test was performed using six Startle Monitor Systems (Kinder Scientific, Julian, CA). Each system, controlled by a PC, was housed in a compact sound attenuation cabinet (35.56 cm wide × 27.62 cm deep × 49.53 cm high). A speaker (diameter: 11 cm) mounted on the cabinet’s ceiling was used to generate acoustic stimuli (70dB–120 dB white noise). The startle response was measured by a piezoelectric sensing platform on the floor, which was calibrated daily. During testing, rats were placed in a rectangular box made of transparent Plexiglas (19 cm wide × 9.8 cm deep × 14.6 high) with an adjustable ceiling positioned atop the box, providing only limited restraint while prohibiting ambulation.

Drugs

The injection solution of phencyclidine hydrochloride (gift from NIDA Chemical Synthesis and Drug Supply Program) was obtained by mixing drugs with 0.9% saline. The injection solution of haloperidol (5.0 mg/ml ampoules, Shanghai Xudong Haipu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) was obtained by mixing the stock with sterile water. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone and quetiapine (gifts from the NIMH drug supply program) were dissolved in 1.0–1.5% glacial acetic acid in distilled water. All injections were administered subcutaneously at a volume of 1 ml/kg. The dose for each antipsychotic drug was carefully chosen based on the following considerations: (1) at the chosen doses, all antipsychotic drugs produce a reliable and comparable level of disruption of avoidance responding which is considered a well-validated animal model for antipsychotic activity (Li et al., 2004, Li et al., 2009a, 2009b, Mead and Li, 2009); (2) all antipsychotic drugs give rise to clinical levels of striatal D2 occupancy (50–80%) at these doses in rats (Kapur et al., 2003); (3) these doses have been thoroughly tested in many PPI studies and show acute efficacy against either PCP or amphetamine-induced PPI disruption (Bakshi and Geyer, 1995, Bakshi, Swerdlow, 1994, Geyer, Krebs-Thomson, 2001, Martinez, Oostwegel, 2000, Swerdlow, Bakshi, 1996, Swerdlow, Weber, 2008). This dose selection also enabled us to evaluate different drugs on a common ground. The PCP at this dose range is shown to induce a robust PPI disruption acutely (Bakshi and Geyer, 1995) and as well as chronically (Martinez, Oostwegel, 2000).

Experiment 1: Effects of repeated haloperidol (0.05 mg/kg, sc) and clozapine (10 mg/kg, sc) treatment on repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced PPI disruption

Rats (n=48) were first handled individually for two days for approximately two minutes each day to minimize stress during behavioral testing. On the first handling day, the rats were acclimated to the prepulse inhibition apparatus for 10 minutes. On the second handling day, the rats were habituated to the PPI test procedure, which was adapted from Culm and Hammer (2004). The PPI session lasted approximately 18 minutes and began with a 5 minute period of 70 dB background noise (which continued throughout the duration of the session) followed by four different trial types: PULSE ALONE trials and three types of PREPULSE + PULSE trials, which consisted of a 20 ms 73, 76, or 82 dB prepulse (3, 6, and 12 dB above background) followed 100 ms later by a 120 dB pulse. Each session was divided into 4 blocks. Blocks 1 and 4 were identical, each consisting of 4 PULSE ALONE trials. Blocks 2 and 3 were also identical and each consisted of 8 PULSE ALONE trials and 5 of each PREPULSE + PULSE trial type. A total of 54 trials were presented during each test session. Trials within each block were presented in a pseudorandom order and were separated by a variable intertrial interval averaging 15 seconds (ranging from 9–21 seconds). Startle magnitude was defined as the maximum force (measured in Newtons) applied by the rat to the startle apparatus recorded over a period of 100 ms beginning at the onset of the pulse stimulus. Between each stimulus trial, 100 ms of activity was recorded when no stimulus was present. These trials were called NOSTIM trials and were not included in the calculation of intertrial intervals. Responses recorded during NOSTIM trials are considered a measure of gross motor activity within the PPI boxes. Startle responses from testing blocks 2 and 3 were used to calculate percent prepulse inhibition (%PPI) for each acoustic prepulse trial type:

One day after the second habituation day, rats were injected subcutaneously with saline and tested for PPI 10 min after injection. The averaged %PPI at three prepulse levels (73, 76 and 82 dB) on this day was used to create matched groups such that all groups had comparable baseline PPI performance prior to the drug tests. Four groups (n=12/group) were formed: VEH (sterile water, sc)+VEH (saline, sc), VEH+PCP, HAL+PCP, and CLZ+PCP and they were subjected to drug testing for 6 consecutive days. During each daily test, rats were first injected with either sterile water, HAL (0.05 mg/kg, sc) or CLZ (10.0 mg/kg, sc), followed by an injection of saline or PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc) 30 min later. Ten min after the second injection, rats were placed in the PPI boxes and tested.

Experiment 2: Effects of repeated olanzapine (2.0 mg/kg, sc), risperidone (1.0 mg/kg, sc) and quetiapine (10.0 mg/kg, sc) treatment on repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced PPI disruption

Experiment 2 tested the potential reversal effect of repeated olanzapine (2.0 mg/kg, sc), risperidone (1.0 mg/kg, sc) and quetiapine (10.0 mg/kg, sc) treatment on repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced PPI disruption. The basic procedure was identical to that of Experiment 1. Sixty rats were assigned to five groups based on the averaged % PPI on the saline day (n=12/group): VEH (sterile water, sc)+VEH (saline, sc), VEH+PCP, OLZ+PCP, RIS+PCP, and QUE+PCP. They were subjected to 6 consecutive drug tests.

Experiment 3: Effects of repeated clozapine (5.0 and 10 mg/kg, sc) treatment on repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced PPI disruption

Experiment 3 was conducted to examine a possible dose-dependent attenuation effect of repeated clozapine treatment on repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced PPI disruption. The basic procedure was identical to that of Experiment 1. Forty-eight rats were assigned to 4 groups based on the averaged % PPI on the saline day (n=12/group): VEH (sterile water, sc)+VEH (saline, sc), VEH+PCP, CLZ-5.0+PCP, and CLZ-10.0+PCP. They were subjected to 6 consecutive drug tests.

Statistical analysis

Percent PPI data for the 6 drug days were presented separately for three prepulse intensities (e.g. 73, 76 and 82 dB). The magnitude of the acoustic startle reflex (ASR) was calculated as the average response on the PULSE ALONE trials, excluding the first and last block of 4 PULSE ALONE trials. The general activity was calculated as the average response on the NOSTIM trials. Percent PPI, ASR and activity data from the drug test period were first analyzed using repeated measures ANOVAs with drug treatment group as a between-subjects factor and test day (i.e. 6) as a within-subjects factor. For PPI data, another within-subjects factor (i.e. 3 prepulse levels) was also included in the analysis. When a significant test day × group interaction was found, the time course of antipsychotic treatment effect on PCP-induced PPI deficit was reanalyzed using repeated measures ANOVA (i.e. 3 prepulse levels × 6 days) involving only one antipsychotic group (e.g. RIS+PCP). One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by post hoc LSD tests were used to identify between-group differences at specific prepulse level on specific days. For all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Experiment 1: Effects of repeated haloperidol (0.05 mg/kg, sc) and clozapine (10 mg/kg, sc) treatment on repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced PPI disruption

PPI

As expected, there was no group difference on the averaged percent PPI on the saline day (F(3, 44) = 0.566, P = 0.641). Analysis of PPI data from the 6 drug test days revealed a main effect of group (F(3, 44) = 18.583, P < 0.001), prepulse level (F(2, 88) = 363.307, P < 0.001) and test day (F(5, 220) = 4.550, P = 0.001), and a significant prepulse level × group interaction (F(6, 88) = 3.805, P = 0.002). This analysis suggests that the PCP effect and antipsychotic treatment effect were stable across the 6 test days (no test day × group interaction) but varied at different prepulse levels. LSD post hoc tests revealed that the VEH+PCP group differed significantly from the VEH+VEH group (P<0.001), indicating a strong PPI disruptive effect of PCP. Importantly, the CLZ+PCP group differed significantly from the VEH+PCP (P < 0.001), indicating an attenuation effect of repeated CLZ on PCP-induced PPI disruption. CLZ at this dose (10.0 mg/kg) did not completely normalize PCP-induced PPI deficit as the CLZ+PCP group still differed significantly from the VEH+VEH group (P = 0.009). Unlike CLZ, HAL did not improve PCP-induced PPI deficits, as evidenced by the lack of significant difference between the HAL+PCP and VEH+PCP group (P = 0.617).

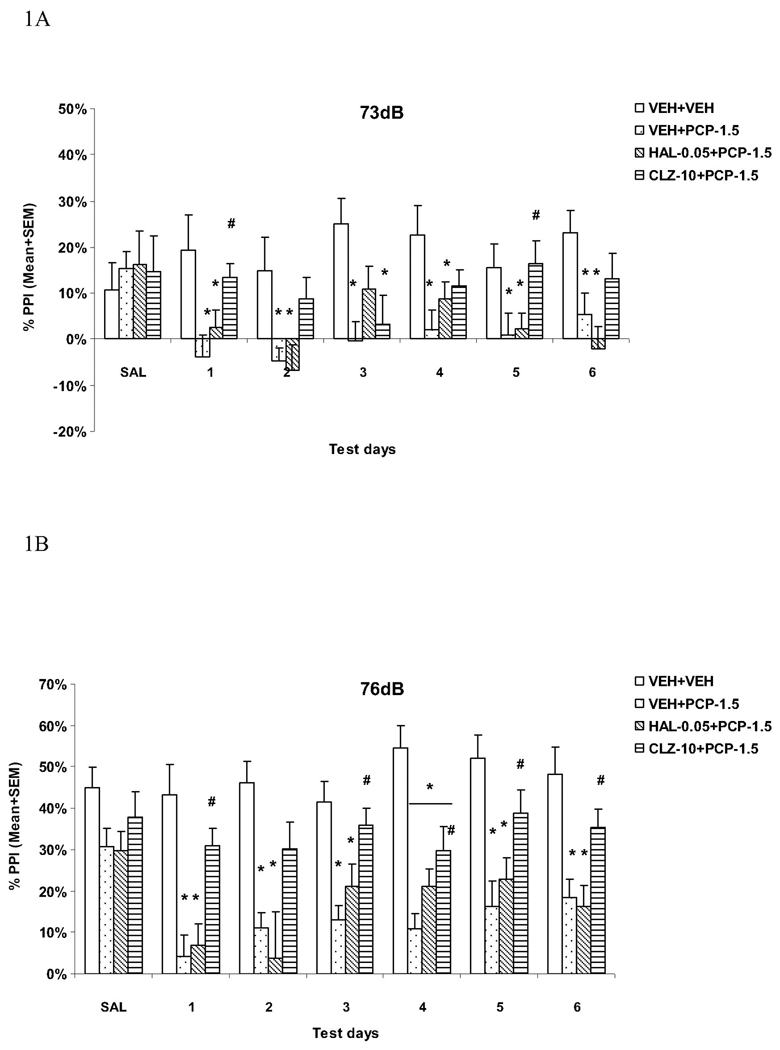

To examine significant group difference at each prepulse level on each drug test day, one-way ANOVAs followed by post hoc LSD tests were used. At the 73 dB prepulse intensity level (Fig. 1A), the VEH+PCP group had significantly lower PPI than the VEH+VEH group on all test days (all Ps < 0.030). The CLZ+PCP group had significantly higher PPI than the VEH+PCP group on days 1 (P = 0.024) and 5 (P = 0.022), whereas the HAL+PCP group did not show such an attenuation effect (all Ps > 0.130). At the 76 dB prepulse intensity level (Fig. 1B), the VEH+PCP and HAL+PCP groups had significantly lower PPI than the VEH+VEH group on all drug test days (all Ps < 0.002). CLZ significantly reduced PCP-induced disruption on all days (Ps < 0.030) except on day 2 (P = 0.069), whereas HAL had no effect (all Ps > 0.136).

Fig. 1.

Effects of repeated haloperidol (0.05 mg/kg, sc) or clozapine (10.0 mg/kg, sc) treatment on the repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced disruption of PPI at the 73 dB (A), 76 dB (B) and 82 dB (C) prepulse levels. *P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+VEH group; #P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+PCP group.

At the 82 dB prepulse intensity level (Fig. 1C), the VEH+PCP and HAL+PCP groups had significantly lower PPI than the VEH+VEH group on all drug test days (all Ps < 0.002). Once again, CLZ significantly reduced PCP-induced disruption on all days (Ps < 0.035) except on day 2 (P = 0.201), whereas HAL had no effect (all Ps > 0.189).

Overall, our data suggests that PCP at the tested dose produced a persistent disruption of sensorimotor gating as measured in the PPI paradigm, especially at the 76 and 82 dB prepulse levels. Pretreatment of CLZ, but not HAL, attenuated PCP-induced PPI deficits and this attenuation started early and was maintained throughout the testing period.

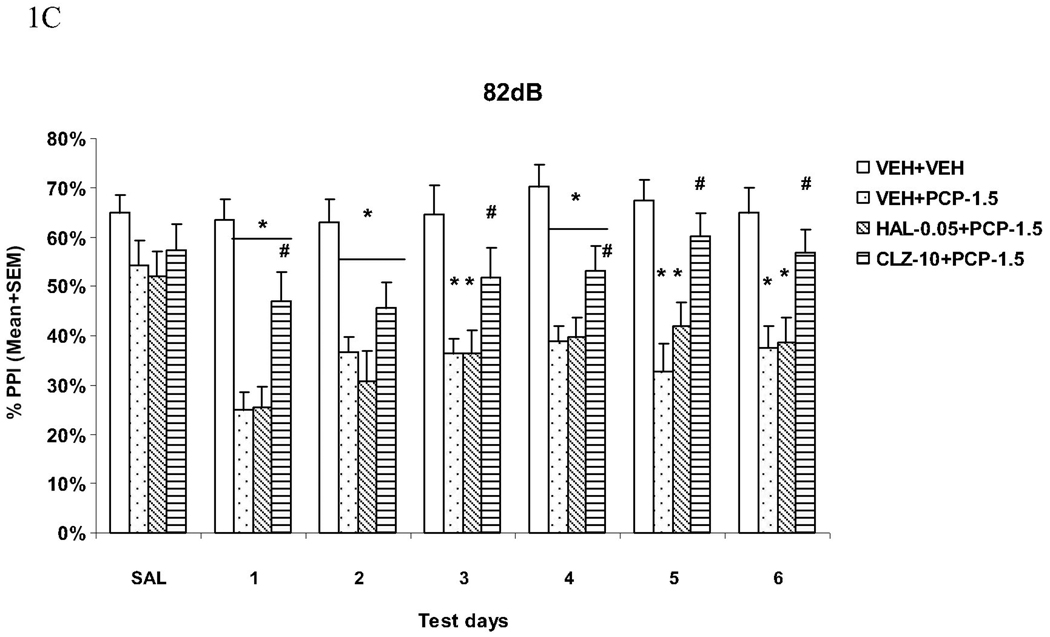

Acoustic startle response (ASR)

The startle magnitudes over the six drug test days were substantially higher in rats that were treated with VEH+PCP or HAL+PCP. Pretreatment of CLZ completely normalized this effect of PCP (Fig. 2A). Repeated measures ANOVA shows a main effect of group (F(3, 44) = 10.394, P < 0.001) and a significant interaction between group and test day (F(15, 220) = 2.692, P = 0.001). Post hoc tests show that the VEH+VEH and CLZ+PCP groups did not differ from each other, but did differ significantly from the VEH+PCP and HAL+PCP groups (Ps = 0.001). Individual one-way ANOVAs followed by LSD post hoc tests on each test day indicated that both the VEH+VEH and CLZ+PCP groups differed significantly from the VEH+PCP and HAL+PCP groups on every test day (all Ps <0.022). Therefore, similar to their effects on PPI, CLZ is categorically different from HAL on PCP-induced increase of startle response.

Fig. 2.

Effects of repeated haloperidol (0.05 mg/kg, sc) or clozapine (10.0 mg/kg, sc) treatment on the repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced increase in the acoustic startle response (ASR) (A) and general activity (B). *P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+VEH group; #P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+PCP group.

General activity

The motor activities recorded during the NOSTIM trials were substantially higher in rats that were treated with VEH+PCP or HAL+PCP. Again, pretreatment of CLZ completely normalized this effect of PCP (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, pretreatment of HAL also reduced this effect of PCP, especially towards the end of drug testing sessions. Repeated measures ANOVA shows a main effect of group (F(3, 44) = 19.611, P < 0.001), a main effect of test day (F(5, 220) = 3.931, P = 0.002), and a significant interaction between group and test day (F(15, 220) = 3.358, P < 0.001). Individual tests on each test day also indicate that the VEH+PCP group differed significantly from the VEH+VEH and CLZ+PCP group on every test day (all Ps < 0.032). The HAL+PCP group differed significantly from the VEH+VEH group only on the first 5 test days (all Ps < 0.013), but not on the last day (P = 0.142) when it also differed significantly from the VEH+PCP group (P = 0.003).

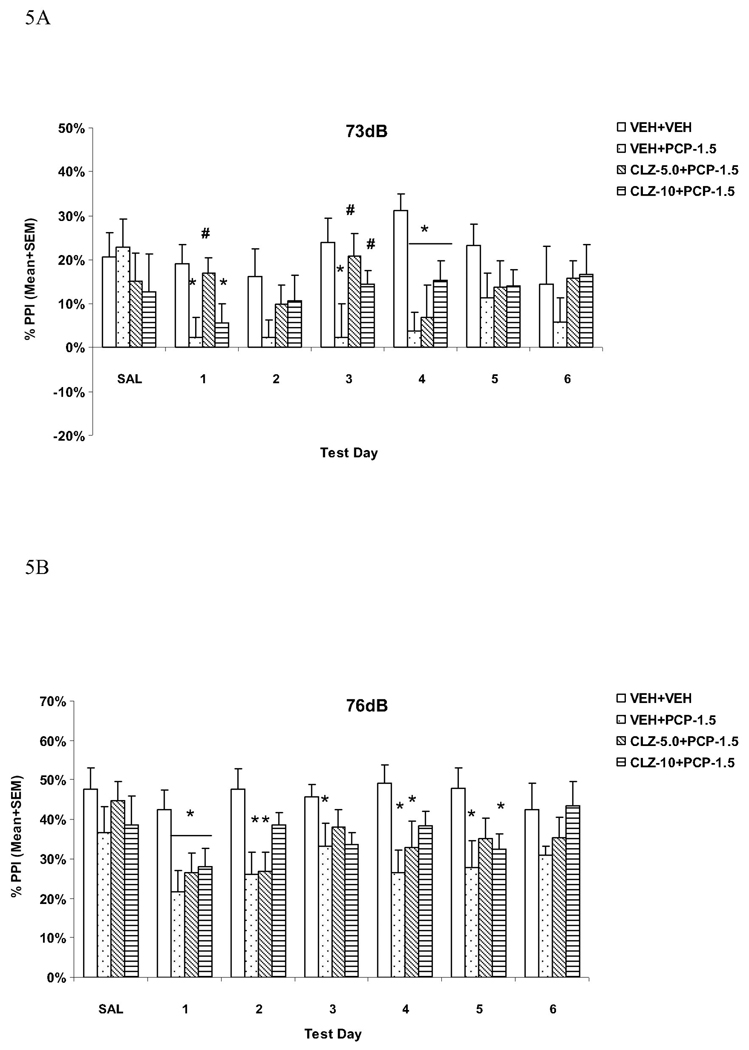

Experiment 2: Effects of repeated olanzapine (2.0 mg/kg, sc), risperidone (1.0 mg/kg, sc) and quetiapine (10.0 mg/kg, sc) treatment on repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced PPI disruption

PPI

Analysis of PPI data from the 6 drug test days revealed a main effect of group (F(4, 55) = 21.178, P < 0.001), prepulse level (F(2, 110) = 734.820, P < 0.001) and test day (F(5, 275) = 10.548, P < 0.001). There was also a significant day × group interaction (F(20, 275) = 1.851, P = 0.016), a significant prepulse level × group interaction (F(8, 110) = 7.316, P < 0.001), and a significant prepulse level × day interaction (F(10, 550) = 2.778, P = 0.002). LSD post hoc tests revealed that the VEH+PCP group differed significantly from the VEH+VEH group (P<0.001), indicating a strong PPI disruptive effect of PCP. Importantly, the RIS+PCP and QUE+PCP group differed significantly from the VEH+PCP (P = 0.005 and 0.001, respectively), indicating an attenuation effect of repeated RIS and QUE on PCP-induced PPI disruption. Both RIS and QUE at the tested doses did not completely normalize PCP-induced PPI deficit as both groups still differed significantly from the VEH+VEH group (Ps < 0.001). Interestingly, the OLZ+PCP group did not differ significantly from the VEH+PCP group (P = 0.698), suggesting a lack of effect with repeated OLZ treatment. Repeated measures ANOVA involving only the RIS+PCP group showed a main effect of test day (F(5, 55) = 9.159, P < 0.001), a main effect of prepulse level (F(2, 22) = 186.463, P < 0.001), and a significant test day × prepulse level interaction (F(10, 110) = 2.030, P =0.037), suggesting that with repeated treatment, risperidone enhanced its effects on PCP-induced PPI disruption. For QUE+PCP group, the main effect of test day was not significant (F(5, 55) = 1.848, P = 0.119), suggesting that the quetiapine’s effect remained stable across the test days.

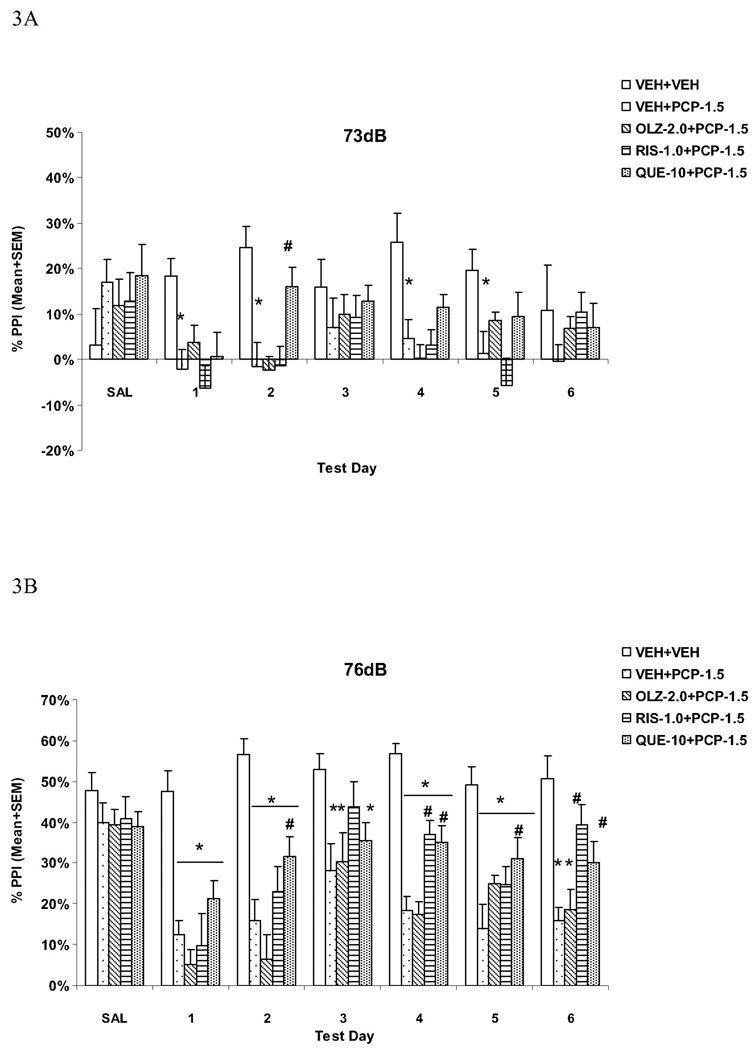

At the 73 dB prepulse intensity level (Fig. 3A), one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc tests showed that the VEH+PCP group had significantly lower PPI than the VEH+VEH group on days 1, 2, 4 and 5 test days (all Ps < 0.010). The QUE+PCP group had significantly higher PPI than the VEH+PCP group only on one test day (day 2, P = 0.006).

Fig. 3.

Effects of repeated olanzapine (2.0 mg/kg, sc), risperidone (1.0 mg/kg, sc), or quetiapine (10.0 mg/kg, sc) treatment on the repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced disruption of PPI at the 73 dB (A), 76 dB (B) and 82 dB (C) prepulse levels. *P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+VEH group; #P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+PCP group.

At the 76 dB prepulse intensity level (Fig. 3B), the VEH+PCP and OLZ+PCP groups had significantly lower PPI than the VEH+VEH group on all drug test days (all Ps < 0.010). RIS significantly reduced PCP-induced disruption on days 4 and 6 (Ps < 0.002). QUE significantly reduced PCP-induced disruption on days 2, 4, 5 and 6 (all Ps < 0.042).

At the 82 dB prepulse intensity level (Fig. 3C), the VEH+PCP and OLZ+PCP groups had significantly lower PPI than the VEH+VEH group on all drug test days (all Ps < 0.002) except on day 3 (Ps > 0.073). Once again, RIS significantly reduced PCP-induced disruption on all test days (Ps < 0.025) except on day 1 (P = 0.121). QUE significantly reduced PCP-induced disruption on days 4, 5 and 6 (all Ps < 0.012).

These results confirmed that PCP at the tested dose is capable of producing persistent PPI deficit. Pretreatment of RIS and QUE, but not OLZ, attenuated PCP-induced PPI deficits. It appears that the attenuation effect of RIS tended to increase while that of QUE maintained throughout the treatment period.

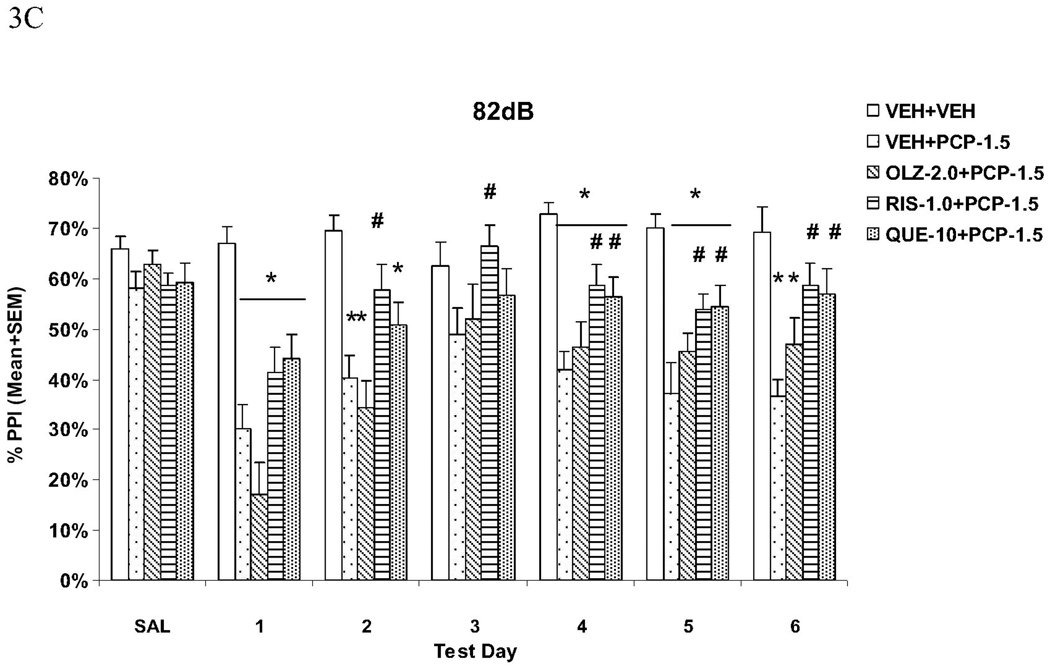

Acoustic startle response (ASR)

The startle magnitudes over the 6 drug test days were substantially higher in rats treated with VEH+PCP, and to a lesser extent, OLZ+PCP. Pretreatment of RIS and QUE, and, to a lesser extent, OLZ, reduced the startle-enhancing effect of PCP (Fig. 4A). Repeated measures ANOVA shows a main effect of group (F(4, 55) = 8.733, P < 0.001), a main effect of test day (F(5, 275) = 6.111, P < 0.001), and a significant group × test day interaction (F(20, 275) = 2.408, P = 0.001). LSD post hoc tests show that the VEH+PCP group differed significantly from all other groups (all Ps < 0.024). Only the RIS+PCP group did not differ significantly from the VEH+VEH group (P = 0.104), suggesting that pretreatment of RIS normalized this effect of PCP. All other groups had significantly higher startle reactivity than the VEH+VEH group (Ps < 0.010). Analysis on each test day indicated that in comparison to the VEH+PCP group, the RIS+PCP and QUE+PCP groups had significantly lower startle magnitude on all 6 test days (all Ps < 0.016) and the OLZ+PCP group on days 1, 2 and 4 (Ps < 0.034). Therefore, all three atypical antipsychotics were effective in reducing PCP-induced increase on startle response, but RIS and QUE at the tested doses had amore robust and consistent effect.

Fig. 4.

Effects of repeated olanzapine (2.0 mg/kg, sc), risperidone (1.0 mg/kg, sc), or quetiapine (10.0 mg/kg, sc) treatment on the repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced increase in the acoustic startle response (ASR) (A) and general activity (B). *P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+VEH group; #P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+PCP group.

General activity

The motor activities recorded during the NOSTIM trials were substantially higher in rats that were treated with VEH+PCP. Again, pretreatment of RIS, QUE and OLZ reduced this effect of PCP (Fig. 4B). Repeated measures ANOVA shows a main effect of group (F(4, 55) = 9.415, P < 0.001), a main effect of test day (F(5, 275) = 10.757, P < 0.001), and a significant interaction between group and test day (F(20, 275) = 6.179, P < 0.001). LSD post hoc tests showed that the VEH+PCP differed significantly from the VEH+VEH, RIS+PCP and QUE+PCP groups (Ps < 0.001), but not from the OLZ+PCP group (P = 0.09). Individual tests on each test day indicate that in comparison to the VEH+PCP group, the three antipsychotic treated groups (i.e. RIS+PCP, QUE+PCP and OLZ+PCP) had significantly lowered motor activity on day 4, 5 and 6 (all Ps < 0.004). In addition, the OLZ+PCP group had significantly enhanced motor activity on day 1 (P = 0.006), whereas the RIS+PCP and QUE+PCP had significantly lowered motor activity on day 2 (Ps < 0.010). Like their effects on PCP-induced increase on startle response, repeated atypical antipsychotic treatment was able to reducing the psychomotor stimulating effect of PCP.

Experiment 3: Effects of repeated clozapine (5.0 and 10 mg/kg, sc) treatment on repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced PPI disruption

PPI

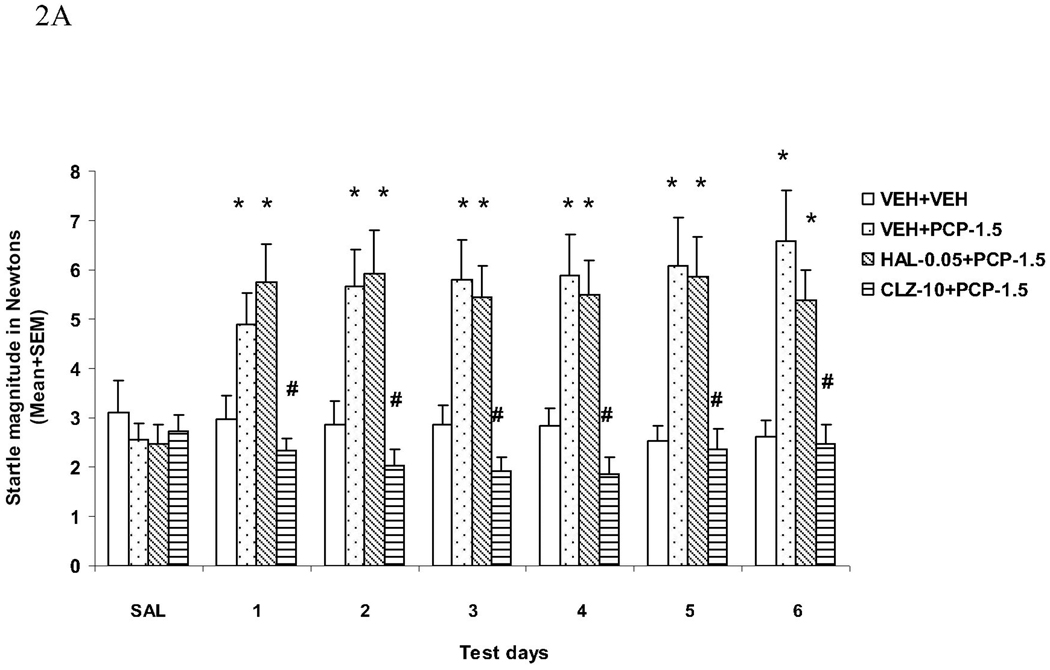

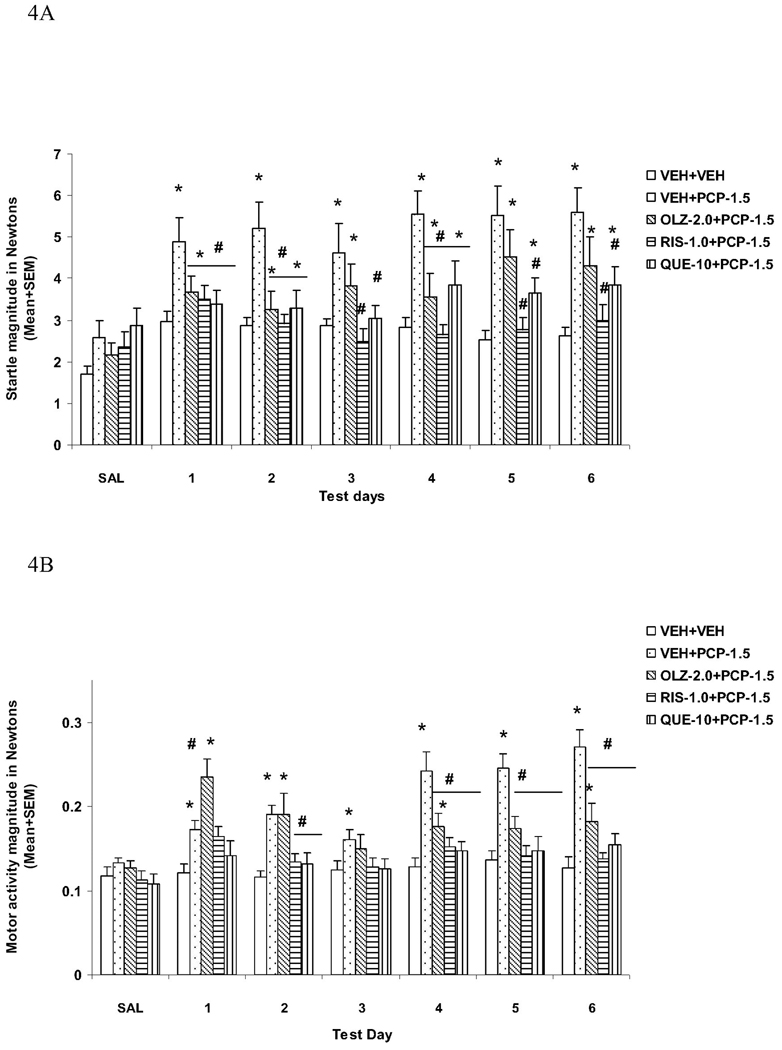

Analysis of PPI data from the 6 drug test days revealed a main effect of group (F(3, 44) = 7.892, P < 0.001), prepulse level (F(2, 88) = 608.366, P < 0.001) and test day (F(5, 220) = 2.675, P = 0.023). LSD post hoc tests revealed that the VEH+PCP group differed significantly from the VEH+VEH group (P < 0.001), indicating a strong PPI disruptive effect of PCP. Importantly, both CLZ groups differed significantly from the VEH+PCP (P = 0.021 for CLZ 5.0 and P = 0.008 for CLZ 10.0), indicating an attenuation effect of repeated CLZ on PCP-induced PPI disruption, which did not change over time (no significant test day × group interaction). CLZ at 5 and 10 mg/kg did not completely normalize PCP-induced PPI deficit as both groups still differed significantly from the VEH+VEH group (P = 0.019 for CLZ 5.0 and P = 0.045 for CLZ 10.0).

At the 73 dB prepulse intensity level (Fig. 5A), one-way ANOVA followed by the post hoc tests showed that the VEH+PCP group had significantly lower PPI than the VEH+VEH group on days 1, 3 and 4 (all Ps < 0.003). In comparison to the VEH+PCP group, the CLZ-5.0+PCP group had significantly higher PPI on days 1 (P = 0.005) and 3 (P = 0.006), and the CLZ-10.0+PCP group had significantly higher PPI on days 1 (P = 0.045).

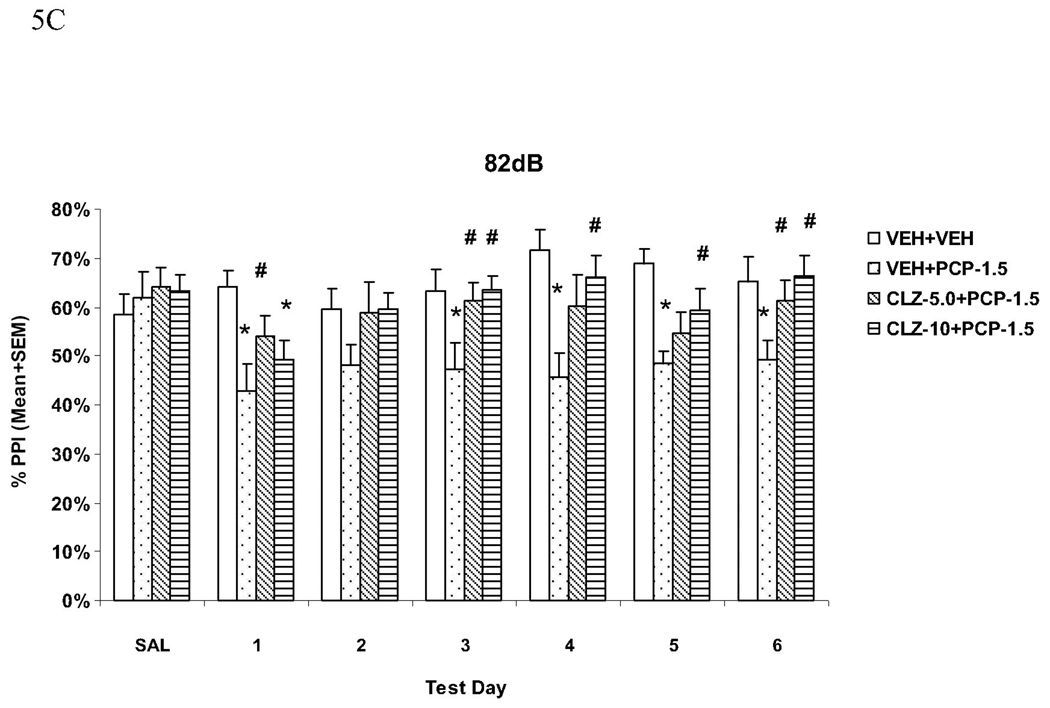

Fig. 5.

Effects of repeated clozapine (5.0 and 10.0 mg/kg, sc) treatment on the repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced disruption of PPI at the 73 dB (A), 76 dB (B) and 82 dB (C) prepulse levels. *P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+VEH group; #P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+PCP group.

At the 76 dB prepulse intensity level (Fig. 5B), the VEH+PCP group had significantly lower PPI than the VEH+VEH group on all drug test days (all Ps < 0.002) except on the last day (P = 0.111). The CLZ-5.0+PCP group had lower PPI on day 1 (P = 0.027), day 2 (P = 0.003), and day 4 (P = 0.036), while the CLZ-10.0+PCP group had lower PPI on days 1 and 5 (Ps = 0.045). Both CLZ groups did not differ significantly from the VEH+PCP group on any of the test days (all Ps > 0.05).

At the 82 dB prepulse intensity level (Fig. 5C), the VEH+PCP group had significantly lower PPI than the VEH+VEH group on all drug test days (all Ps < 0.009) except on day 2 (P = 0.070). In comparison to the VEH+PCP group, the CLZ-5.0+PCP group had significantly higher PPI on days 1, 3 and 6 (all Ps < 0.040), and the CLZ-10.0+PCP group had significantly higher PPI on the last four days (all Ps < 0.041), indicating a clear attenuation effect of repeated CLZ on PCP-induced PPI disruption.

These results confirmed that pretreatment of CLZ at both 5.0 mg/kg and 10.0 mg/kg were equally effective in attenuating PCP-induced PPI disruption. This attenuation effect was most apparent at the 82 dB prepulse level and was maintained throughout the testing period.

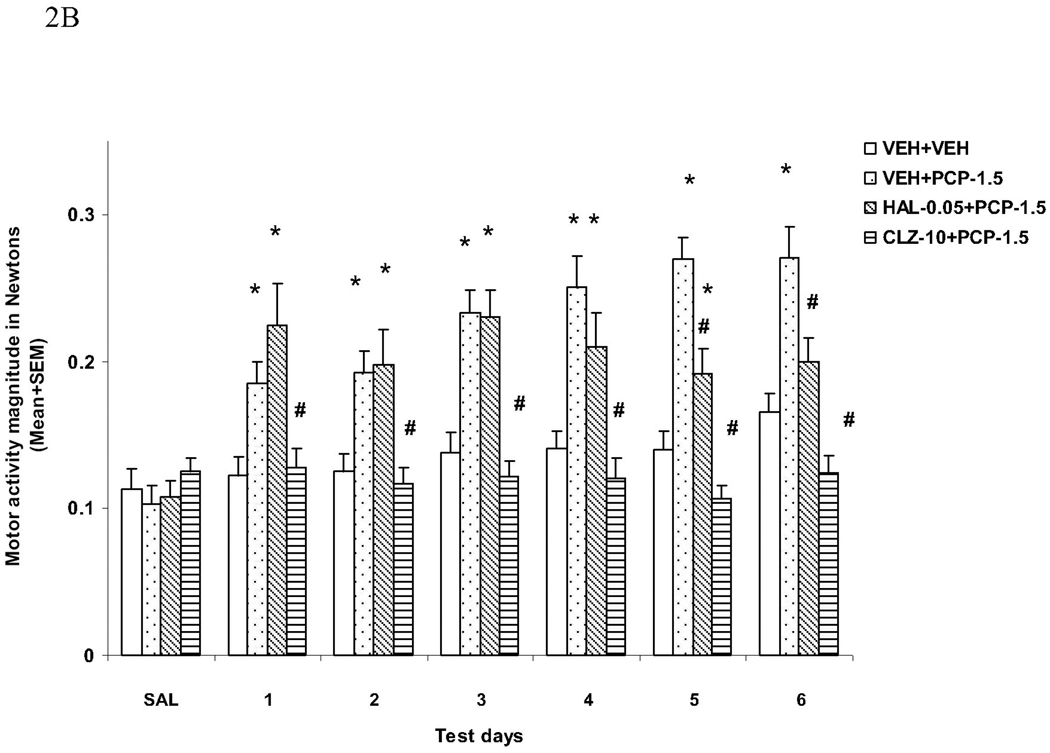

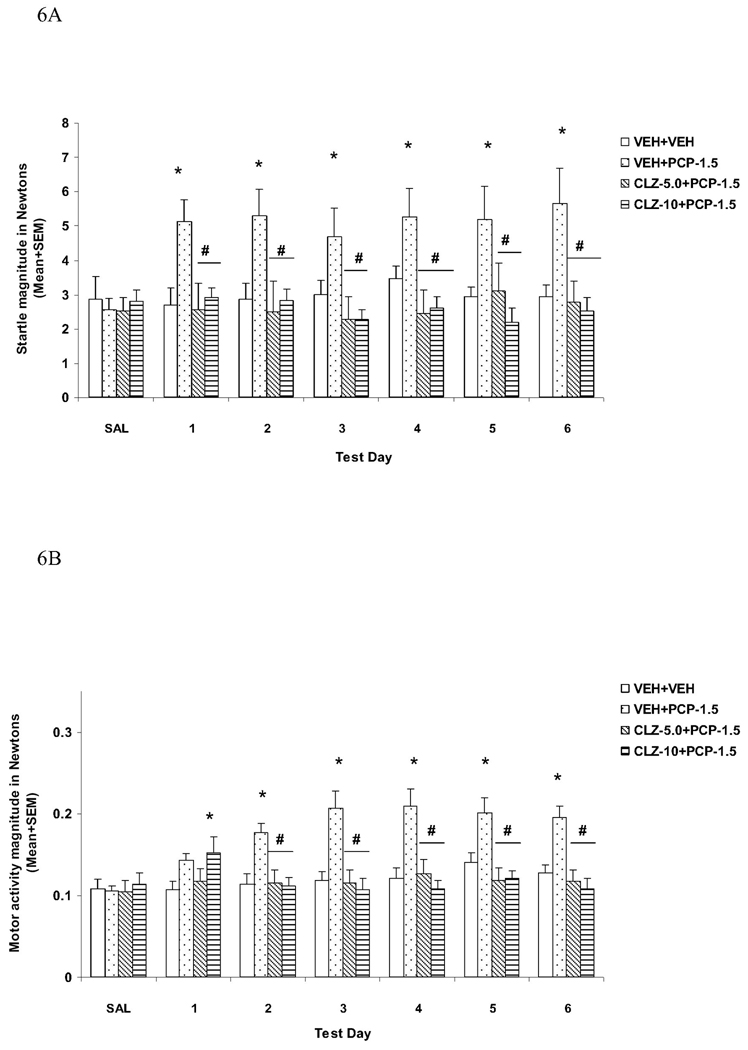

Acoustic startle response (ASR)

The startle magnitudes over the six drug test days were substantially higher in rats from the VEH+PCP group. Pretreatment of CLZ at both doses completely normalized this effect of PCP (Fig. 6A). Repeated measures ANOVA shows a main effect of group (F(3, 44) = 16.721, P < 0.001). Post hoc tests show that the VEH+PCP group differed significantly from all other three groups (all Ps < 0.001), which did not differ from each other (all Ps > 0.333). Individual one-way ANOVAs followed by LSD post hoc tests revealed that the VEH+PCP group differed significantly from all other groups on every test day (all Ps < 0.007).

Fig. 6.

Effects of repeated clozapine (5.0 and 10.0 mg/kg, sc) treatment on the repeated PCP (1.5 mg/kg, sc)-induced increase in the acoustic startle response (ASR) (A) and general activity (B). *P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+VEH group; #P<0.05 in comparison to the VEH+PCP group.

General activity

The motor activities recorded during the NOSTIM trials were substantially higher in rats that were treated with VEH+PCP. Again, pretreatment of CLZ at both doses completely normalized this effect of PCP (Fig. 6B). Repeated measures ANOVA shows a main effect of group (F(3, 44) = 8.180, P < 0.001), a main effect of test day (F(5, 220) = 2.518, P = 0.031), and a significant interaction between group and test day (F(15, 220) = 5.098, P < 0.001). Post hoc tests show that the VEH+PCP group differed significantly from all other three groups (all Ps < 0.001), which did not differ from each other (all Ps > 0.840). Individual tests on each test day also indicate that the VEH+PCP group differed significantly from the VEH+VEH group on every test day (all Ps < 0.004) except on day 1 (P = 0.077). Both CLZ groups also differed significantly from the VEH+PCP group on days 1 to 6 (all Ps < 0.002).

Discussion

As hypothesized, the present study shows that repeated treatment of three atypical antipsychotic drugs, clozapine, risperidone and quetiapine reduced the PPI deficit induced by repeated administration of PCP. In contrast, repeated treatment of haloperidol and olanzapine was ineffective. The PPI effects of these drugs were dissociable from their effects on startle response and general activity. For example, olanzapine and haloperidol had no effect on PCP-induced PPI deficit, but were able to reduce PCP-induced increase in startle response and general motor activity. Finally, the magnitude of the attenuation effect of repeated clozapine, risperidone and quetiapine on PCP-induced PPI disruption was dependent on the prepulse level. It was most stable and conspicuous at a higher prepulse level (e.g. 82 dB) than at a lower level (e.g. 73 dB).

It has been suggested that the acute PCP-PPI model is able to differentiate atypical from typical antipsychotics based on their acute effects in this model (Geyer and Ellenbroek, 2003). Typical antipsychotics such as haloperidol are ineffective in reducing the effects of PCP (see a comprehensive review, Geyer, Krebs-Thomson, 2001). Our current result is consistent with this general observation, suggesting that the lack of haloperidol effect is due to its intrinsic inability to antagonize PCP in this model. Studies on atypical antipsychotics so far have yielded inconsistent results (Geyer, Krebs-Thomson, 2001, Swerdlow, Bakshi, 1996). The majority of studies show that clozapine (Bakshi, Swerdlow, 1994), olanzapine (Bakshi and Geyer, 1995, Wiley and Kennedy, 2002), risperidone (Pouzet et al., 2002b) and quetiapine (Swerdlow, Bakshi, 1996) reduce PCP-induced PPI disruption. Others, including our own, have failed to find such an ameliorating effect with clozapine (Pouzet et al., 2002a, Schwabe et al., 2005, Sun et al., 2010, Wiley and Kennedy, 2002), olanzapine (Fejgin et al., 2007), and risperidone (Swerdlow, Bakshi, 1996). These inconsistent findings are likely due to methodological differences such as PPI testing procedure, testing apparatus, pulse and prepulse parameters, drug doses, administration route, rat strains, etc. as opposed to a total lack of effects. In this regard, the PCP dose may be an important factor. For instance, Sun et al. (2010) failed to observe any reversal effect of clozapine (10 mg/kg) against the PPI deficit induced by PCP (2.0 mg/kg). However, the same dose of clozapine reduced the effect of PCP at 1.5 mg/kg in the present study. Similarly, Swerdlow et al. (1996) found that quetiapine (5.0–7.5 mg/kg) reversed the effect of a lower dose of PCP (1.25 mg/kg). When PCP at 1.5 mg/kg was used, acute quetiapine (10 mg/kg) was unable to significantly reverse its disruption (Fig. 3). The dose of antipsychotic drugs is certainly another important factor. For example, our failure to observe a reversal effect with olanzapine may be due to the fact that a lower dose of olanzapine (2.0 mg/kg) was used. Bakshi and Geyer (1995) showed that olanzapine’s effect in the PCP-PPI model was dose-dependent and it only became effective when the doses reached 5.0 mg/kg. Using the same procedure as described in this study, we recently confirmed the lack of effect of repeated olanzapine treatment at 1.0 and 2.0 mg/kg on PCP (1.5 mg/kg)-induced PPI disruption (unpublished observation).

In contrast to many studies on acute effects of antipsychotic drugs in deficient PPI models, there are only a handful of studies that examined the time course of repeated treatment effect of antipsychotics on PPI deficits induced by NMDA antagonists. They all focused on typical antipsychotic haloperidol and showed that chronic treatment with this drug (1 mg/kg/day) via osmotic minipumps or drinking water attenuated but not completely normalized PCP-induced disruption of PPI (Martinez, Oostwegel, 2000, Pietraszek and Ossowska, 1998). They also reported that short-term treatment (4–7 days) was ineffective. In light of these findings, the lack of haloperidol effect in the present study may be due to inadequate treatment duration or mode of drug delivery, thus longer treatment and continuous dopamine D2 occupancy achieved via osmotic minipump delivery (Kapur, VanderSpek, 2003) may have produced statistically significant effects. This possibility needs to be examined in future study.

The present study revealed that repeated treatment with clozapine, risperidone and quetiapine maintained or progressively enhanced their antagonistic effects against PCP-induced PPI deficit. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report that shows a time-dependent effect of atypicals in the PCP-PPI model. In a related work, Feifel et al. (2007) found a similar effect with risperidone and clozapine in the vasopressin deficient Brattleboro (BRAT) rats (a natural model for sensorimotor deficits). They reported that 16-day treatment with risperidone (1.0 mg/kg) and clozapine (7.5 mg/kg), but not haloperidol (0.5 mg/kg), increased PPI to a greater extent than only one day treatment with these antipsychotic drugs. The importance of our finding is that the overall pattern of change induced by repeated clozapine, risperidone and quetiapine treatment resembles what we have found in the conditioned avoidance response model and the PCP hyperlocomotion model (Li, Fletcher, 2007, Li, Sun, 2010, Mead and Li, 2010, Sun, Hu, 2009). It suggests that there may be a commonality among these models in detecting antipsychotic-like activity. It also indicates that, similar to the repeated conditioned avoidance response model and the PCP hyperlocomotion model, the repeated PCP-PPI model is also capable of capturing the time course of antipsychotic action, at least for the three atypicals (i.e. clozapine, risperidone and quetiapine). One surprising finding is that olanzapine 2.0 mg/kg failed to show any effect, although this dose of olanzapine shows a robust enhanced inhibition on conditioned avoidance response and on PCP-induced increase in locomotor activity with repeated treatment. From this perspective, the conditioned avoidance response and PCP hyperlocomotion models may be more sensitive to the intrinsic “antipsychotic activity” than the repeated PCP-PPI model. Even within the PPI model, among the three behavioral measures typically reported by many studies (i.e. PPI, startle reactivity and general motor activity), PPI seems least sensitive and consistent to a treatment effect of an antipsychotic drug. For instance, in Experiment 1, repeated haloperidol treatment significantly reduced PCP-induced increase on motor activity on days 5 and 6, but it did not reduce PCP-induced PPI disruption at any prepulse level on any day. In Experiment 2, repeated olanzapine treatment reduced PCP-induced increase in startle response and motor activity, had little effect on PCP-induced PPI disruption. Similarly, in both Experiment 1 and 3, repeated clozapine consistently reduced PCP-induced increase in startle reactivity and motor activity throughout the testing period and showed a rather good consistence between the two experiments (Fig. 2 and Fig. 6), however, its effect on PCP-induced PPI disruption was not stabilized until the 2–3 days of testing and it showed large variations at the different prepulse levels and between the experiments. For example, clozapine’s attenuation effect on PPI at the 76 dB level found in Experiment 1 was not replicated in Experiment 3. It appears that the measurements of startle reactivity and general motor activity detect a common treatment effect of antipsychotics better than PPI. One difficulty in detecting a robust and shared effect on PPI may be due to the complex psychological and neurobiological processes involved in PCP-induced PPI deficit (Swerdlow, Weber, 2008).

Mechanisms underlying the PCP-induced PPI deficit and its attenuation by repeated treatment with clozapine, risperidone and quetiapine are not known. PCP is a drug of abuse that has a wide range of psychotomimetic effects in humans (Jentsch and Roth, 1999). Besides blocking NMDA receptor channels, PCP also enhances serotonergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex (Abekawa et al., 2007, Maurel-Remy et al., 1995, Millan et al., 1999). One interesting possibility is that PCP may disrupt PPI by stimulating 5-HT2A receptors, and antipsychotics may reverse this effect by down-regulating 5-HT2A receptors and concomitantly decreasing PCP-induced dopamine and 5-HT increases in the prefrontal cortex. This hypothesis is supported by the findings that the ability of antipsychotics to restore PPI in PCP-treated rats correlated significantly with their affinity for 5-HT2A receptors (Yamada et al., 1999) and repeated administration of clozapine causes a down-regulation of 5-HT2A receptors in the prefrontal cortex (Doat-Meyerhoefer et al., 2005). Another possibility is that antipsychotics achieve their efficacy through action on α1-adrenergic receptors (Bakshi and Geyer, 1997). All antipsychotic drugs tested here have an appreciable antagonistic action on α1-adrenergic receptors (Miyamoto, Duncan, 2005). Bakshi and Geyer (1997) also reported that the α1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin can reduce the disruptive effect of PCP on PPI. Therefore, it is possible that clozapine, risperidone and quetiapine may reduce the effects of PCP by blocking α1-adrenergic receptors. If future work demonstrates that repeated haloperidol and olanzapine could also reverse the disruptive effect of PCP on PPI, it would provide strong support for this hypothesis. The outcome of this line of research may shed light on the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and the molecular mechanisms responsible for antipsychotic action.

We should point out several limitations with the current report. First, in this study, we only used one or two doses of these drugs, and thus the effect (or no-effects) may be related to the dose used in this study. Second, we merely tested their effects on PCP-induced PPI deficits, but there are other transmitter systems (e.g., dopamine, serotonin) that are also involved in deficient sensorimotor gating. Using these transmitter systems to induce deficient PPI may have resulted in different outcome. Third, we did not test how antipsychotics by themselves would affect PPI, thus, it is difficult to determine whether the attenuation effect was due to their specific effects on PCP or their intrinsic potentiating effect on normal level of PPI. Finally, the baseline levels of PPI, experimental parameters, and testing schedule are important determinants of drug effects (Barrett and Bergman, 2008, Geyer, Krebs-Thomson, 2001). Thus the generalization of the drug effects found in this report could not be made until they have been rigorously tested under a broad range of conditions.

Understanding how repeated antipsychotic treatment affects PPI deficits induced by psychotomimetic drugs is important for identification of the mechanisms underlying the clinically relevant action of antipsychotics. The present study provides another animal preparation for studying antipsychotic drugs. Together with the conditioned avoidance response model and the PCP-induced hyperlocomotion model based on repeated treatment regimens (Li, Fletcher, 2007, Li, Sun, 2010, Sun, Hu, 2009), the repeated PCP-PPI model could help enhance our understanding of the neurobiological and behavioral mechanisms of antipsychotic action which in turn, may help understand the neurobiological and behavioral mechanisms of psychosis.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded in part by a research grant (07R-1775) from the Stanley Medical Research Institute and by the NIMH grant (R01MH085635) to Professor Ming Li. We thank Ron Hammer Jr. for his generous help on PPI procedure. We also thank Mr. Tao Sun for his technical support for this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abekawa T, Ito K, Koyama T. Different effects of a single and repeated administration of clozapine on phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotion and glutamate releases in the rat medial prefrontal cortex at short- and long-term withdrawal from this antipsychotic. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2007;375:261–271. doi: 10.1007/s00210-007-0154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agid O, Kapur S, Arenovich T, Zipursky RB. Delayed-onset hypothesis of antipsychotic action: a hypothesis tested and rejected. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:1228–1235. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.12.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agid O, Seeman P, Kapur S. The "delayed onset" of antipsychotic action--an idea whose time has come and gone. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2006;31:93–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen MP, Pouzet B. Effects of acute versus chronic treatment with typical or atypical antipsychotics on d-amphetamine-induced sensorimotor gating deficits in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:291–304. doi: 10.1007/s002130100818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi VP, Geyer MA. Antagonism of phencyclidine-induced deficits in prepulse inhibition by the putative atypical antipsychotic olanzapine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;122:198–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02246096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi VP, Geyer MA. Phencyclidine-induced deficits in prepulse inhibition of startle are blocked by prazosin, an alpha-1 noradrenergic antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:666–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi VP, Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA. Clozapine antagonizes phencyclidine-induced deficits in sensorimotor gating of the startle response. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;271:787–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JE, Bergman J, Peter B. Dews and pharmacological studies on behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:683–690. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.139261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briody S, Boules M, Oliveros A, Fauq I, Richelson E. Chronic NT69L potently prevents drug-induced disruption of prepulse inhibition without causing tolerance. Behav Brain Res. 2010;207:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culm KE, Hammer RP., Jr Recovery of sensorimotor gating without G protein adaptation after repeated D2-like dopamine receptor agonist treatment in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:487–494. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doat-Meyerhoefer MM, Hard R, Winter JC, Rabin RA. Effects of clozapine and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine [DOM] on 5-HT2A receptor expression in discrete brain areas. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81:750–757. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley R, Rabinowitz J, Medori R. Time course for antipsychotic treatment response in first-episode schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:743–745. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feifel D, Melendez G, Priebe K, Shilling PD. The effects of chronic administration of established and putative antipsychotics on natural prepulse inhibition deficits in Brattleboro rats. Behav Brain Res. 2007;181:278–286. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feifel D, Priebe K. The effects of subchronic haloperidol on intact and dizocilpine-disrupted sensorimotor gating. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;146:175–179. doi: 10.1007/s002130051103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fejgin K, Safonov S, Palsson E, Wass C, Engel JA, Svensson L, et al. The atypical antipsychotic, aripiprazole, blocks phencyclidine-induced disruption of prepulse inhibition in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0658-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Ellenbroek B. Animal behavior models of the mechanisms underlying antipsychotic atypicality. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:1071–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer MA, Krebs-Thomson K, Braff DL, Swerdlow NR. Pharmacological studies of prepulse inhibition models of sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia: a decade in review. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;156:117–154. doi: 10.1007/s002130100811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick ID, Shkedy Z, Schreiner A. Differential early onset of therapeutic response with risperidone vs conventional antipsychotics in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21:261–266. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200609000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jentsch JD, Roth RH. The neuropsychopharmacology of phencyclidine: from NMDA receptor hypofunction to the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:201–225. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jibson MD, Tandon R. New atypical antipsychotic medications. J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, Arenovich T, Agid O, Zipursky R, Lindborg S, Jones B. Evidence for onset of antipsychotic effects within the first 24 hours of treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:939–946. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S, VanderSpek SC, Brownlee BA, Nobrega JN. Antipsychotic dosing in preclinical models is often unrepresentative of the clinical condition: a suggested solution based on in vivo occupancy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:625–631. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.046987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S, Busch R, Hamann J, Kissling W, Kane JM. Early-onset hypothesis of antipsychotic drug action: a hypothesis tested, confirmed and extended. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1543–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Davidson P, Budin R, Kapur S, Fleming AS. Effects of typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs on maternal behavior in postpartum female rats. Schizophr Res. 2004;70:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Fletcher PJ, Kapur S. Time course of the antipsychotic effect and the underlying behavioral mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:263–272. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, He W, Mead A. An investigation of the behavioral mechanisms of antipsychotic action using a drug-drug conditioning paradigm. Behav Pharmacol. 2009a;20:184–194. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32832a8f66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, He W, Mead A. Olanzapine and risperidone disrupt conditioned avoidance responding in phencyclidine-pretreated or amphetamine-pretreated rats by selectively weakening motivational salience of conditioned stimulus. Behav Pharmacol. 2009b;20:84–98. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283243008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Sun T, Zhang C, Hu G. Distinct neural mechanisms underlying acute and repeated administration of antipsychotic drugs in rat avoidance conditioning. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212:45–57. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1925-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez ZA, Oostwegel J, Geyer MA, Ellison GD, Swerdlow NR. "Early" and "late" effects of sustained haloperidol on apomorphine- and phencyclidine-induced sensorimotor gating deficits. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;23:517–527. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel-Remy S, Bervoets K, Millan MJ. Blockade of phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotion by clozapine and MDL 100,907 in rats reflects antagonism of 5-HT2A receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;280:R9–R11. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00333-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead A, Li M. Avoidance-suppressing effect of antipsychotic drugs is progressively potentiated after repeated administration: an interoceptive drug state mechanism. J Psychopharmacol. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0269881109102546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mead A, Li M. Avoidance-suppressing effect of antipsychotic drugs is progressively potentiated after repeated administration: an interoceptive drug state mechanism. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1045–1053. doi: 10.1177/0269881109102546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Brocco M, Gobert A, Joly F, Bervoets K, Rivet J, et al. Contrasting mechanisms of action and sensitivity to antipsychotics of phencyclidine versus amphetamine: importance of nucleus accumbens 5-HT2A sites for PCP-induced locomotion in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4419–4432. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto S, Duncan GE, Marx CE, Lieberman JA. Treatments for schizophrenia: a critical review of pharmacology and mechanisms of action of antipsychotic drugs. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:79–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietraszek M, Ossowska K. Chronic treatment with haloperidol diminishes the phencyclidine-induced sensorimotor gating deficit in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1998;357:466–471. doi: 10.1007/pl00005194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouzet B, Didriksen M, Arnt J. Effects of the 5-HT(6) receptor antagonist, SB-271046, in animal models for schizophrenia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002a;71:635–643. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00743-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouzet B, Didriksen M, Arnt J. Effects of the 5-HT(7) receptor antagonist SB-258741 in animal models for schizophrenia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002b;71:655–665. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00744-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raedler TJ, Schreiner A, Naber D, Wiedemann K. Early onset of treatment effects with oral risperidone. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon GC, Viik K. Prepulse inhibition as a screening test for potential antipsychotics. Drug Development Research. 1991;23:91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rueter LE, Ballard ME, Gallagher KB, Basso AM, Curzon P, Kohlhaas KL. Chronic low dose risperidone and clozapine alleviate positive but not negative symptoms in the rat neonatal ventral hippocampal lesion model of schizophrenia. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2004;176:312–319. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1897-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe K, Brosda J, Wegener N, Koch M. Clozapine enhances disruption of prepulse inhibition after sub-chronic dizocilpine- or phencyclidine-treatment in Wistar rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;80:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Hu G, Li M. Repeated antipsychotic treatment progressively potentiates inhibition on phencyclidine-induced hyperlocomotion, but attenuates inhibition on amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion: relevance to animal models of antipsychotic drugs. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;602:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T, Zhao C, Hu G, Li M. Iptakalim: a potential antipsychotic drug with novel mechanisms? Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;634:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Bakshi V, Geyer MA. Seroquel restores sensorimotor gating in phencyclidine-treated rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:1290–1299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Geyer MA. Clozapine and haloperidol in an animal model of sensorimotor gating deficits in schizophrenia. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;44:741–744. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90193-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Keith VA, Braff DL, Geyer MA. Effects of spiperone, raclopride, SCH 23390 and clozapine on apomorphine inhibition of sensorimotor gating of the startle response in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;256:530–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow NR, Weber M, Qu Y, Light GA, Braff DL. Realistic expectations of prepulse inhibition in translational models for schizophrenia research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;199:331–388. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1072-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL, Kennedy KL. Evaluation of the efficacy of antipsychotic attenuation of phencyclidine-disrupted prepulse inhibition in rats. J Neural Transm. 2002;109:523–535. doi: 10.1007/s007020200043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Harano M, Annoh N, Nakamura K, Tanaka M. Involvement of serotonin 2A receptors in phencyclidine-induced disruption of prepulse inhibition of the acoustic startle in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:832–838. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]