Non-technical summary

The inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA activates two distinct receptors of which the GABAA receptor is mainly a Cl− conducting ion channel. The proper functioning of inhibition at the GABAA receptor depends on the ionic gradient prevailing during receptor activation, and in epilepsy there is an aberrant Cl− gradient. Using rat and human cortical neurones and pharmacological inhibitors, we calculated the contributions of neuronal Cl− extrusion by the Na+–K+–2Cl− transporter NKCC1, the K+-coupled Cl− transporter KCC2 and the voltage-gated Cl− channel ClC2. We found that KCC2 is the major route of Cl− extrusion and that reduced KCC2 Cl− extrusion is likely to be the initial step of disturbed Cl− regulation. The results contribute to our understanding of epilepsy.

Abstract

Abstract

Considerable evidence indicates disturbances in the ionic gradient of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition of neurones in human epileptogenic tissues. Two contending mechanisms have been proposed, reduced outward and increased inward Cl− transporters. We investigated the properties of Cl− transport in human and rat neocortical neurones (layer II/III) using intracellular recordings in slices of cortical tissue. We measured the alterations in reversal potential of the pharmacologically isolated inhibitory postsynaptic potential mediated by GABAA receptors (IPSPA) to estimate the ionic gradient and kinetics of Cl− efflux after Cl− injections before and during application of selected blockers of Cl− routes (furosemide, bumetanide, 9-anthracene carboxylic acid and Cs+). Neurones from human epileptogenic cortex exhibited a fairly depolarized reversal potential of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition (EIPSP-A) of −61.9 ± 8.3 mV. In about half of the neurones, the EIPSP-A averaged −55.2 ± 5.7 mV, in the other half, 68.6 ± 2.3 mV, similar to rat neurones (−68.9 ± 2.6 mV). After injections of Cl−, IPSPA recovered in human neurones with an average time constant (τ) of 19.0 ± 9.6 s (rat neurones: 7.2 ± 2.4 s). We calculated Cl− extrusion rates (1/τ) via individual routes from the τ values obtained in different experimental conditions, revealing that, for example, the K+-coupled Cl− transporter KCC2 comprises 45.3% of the total rate in rat neurones. In human neurones, the total rate of Cl− extrusion was 63.9% smaller, and rates via KCC2, the Na+–K+–2Cl− transporter NKCC1 and the voltage-gated Cl− channel ClC were smaller than in rat neurones by 80.0%, 61.7% and 79.9%, respectively. The rate via anion exchangers conversely was 14.4% larger in human than in rat neurones. We propose that (i) KCC2 is the major route of Cl− extrusion in cortical neurones, (ii) reduced KCC2 is the initial step of disturbed Cl− regulation and (iii) reductions in KCC2 contribute to depolarizing EIPSP-A of neurones in human epileptogenic neocortex.

Introduction

Synaptically released GABA activates two molecularly and pharmacologically distinct receptors, coined GABAA and GABAB (see Teichgräber et al. 2009). Disturbance of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition is well known to contribute to hyperexcitability in rodent models of epilepsy. Early experiments in vitro demonstrated that blockade of GABAA receptors with antagonists generates paroxysmal depolarizations resembling in vivo epileptogenic activity (Gutnick et al. 1982). Indeed, a decreased GABAA receptor function, via altered subunit expression, was shown in the hippocampus of a rodent model of epilepsy (e.g. Rice et al. 1996). Conversely, several drugs used in epilepsy therapy (e.g. benzodiazepines, phenytoin) augment GABAA receptor function (Polc & Haefely, 1976; Deisz & Lux, 1977; Aickin et al. 1981; Granger et al. 1995).

However, the proper function of GABAergic transmission depends not only on intact receptors and sufficient GABA release, but also on the ionic gradient prevailing during receptor activation. The reversal potential of GABAA receptor-mediated responses (EIPSP-A) is dominated by the Cl− gradient across the neuronal membrane (Deisz & Lux, 1982; Thompson et al. 1988a). However, the partial HCO3− permeability of GABAA receptors (Bormann et al. 1987; Kaila et al. 1993), with a HCO3− reversal potential of about −10 mV (see Alvarez-Leefmans, 1990), causes a disparity (about 10 mV) between the Cl− gradient (ECl) and the EIPSP-A in the neocortex (Kaila et al. 1993). In various neurones, [Cl−]i is maintained below passive distribution by an NH4+-sensitive (Lux, 1971; Llinás et al. 1974; Raabe & Gumnit, 1975; Aickin et al. 1982; Deisz & Lux, 1982; Thompson et al. 1988a; Williams & Payne, 2004) and furosemide-sensitive Cl− outward transport mechanism (Deisz & Lux, 1982; Misgeld et al. 1986; Thompson et al. 1988a; Titz et al. 2006), coupled to K+ (Aickin et al. 1982; Deisz & Lux, 1982). A K+-coupled Cl− transporter was cloned, revealing a neurone-specific isoform, KCC2 (Payne et al. 1996), which is the molecular substrate for K+-coupled Cl− outward transport in central neurones (for review, see Gamba, 2005).

Previous evidence suggests that relatively high [Cl−]i depends on inward transport in some peripheral neurones (for brief review see Delpire, 2000). The molecular basis for this is probably the NKCC family of Na+/K+-coupled Cl− transporters (for review, see Gamba, 2005). More recent evidence indicates that the isoform NKCC1 mediates inward Cl− transport in central neurones (e.g. Dzhala et al. 2005; Achilles et al. 2007; Brumback & Staley, 2008). On the other hand, the selective antagonist bumetanide reduces Cl− outward transport in the neocortex (Thompson et al. 1988b). Nevertheless, these two potentially opposing transport mechanisms play a crucial role during postnatal development (for review see Ben-Ari, 2002). Between postnatal days 11 and 16 a slow Cl− outward transport and an EIPSP-A less negative than resting membrane potential (Em) were shown in the rat neocortex (Luhmann & Prince, 1991), consistent with a presence of NKCC1 at a fairly low rate (Achilles et al. 2007). Molecular analysis revealed that NKCC1 expression in the neocortex is much higher until postnatal day 10 (about 1500%) compared with the adult level and then progressively declines. Conversely, expression of KCC2 is relatively low at postnatal day 10 (about 10%vs. adult) and increases to adult levels (Dzhala et al. 2005). The postnatal increase in KCC2 expression (Rivera et al. 1999; Dzhala et al. 2005) shifts the polarity of GABAergic responses from depolarization to the mature (i.e. inhibitory) behaviour of cortical EIPSP-A close to Em (Connors et al. 1988; Thompson et al. 1988a; Deisz & Prince, 1989; Kaila et al. 1993).

Other pathways have to be considered in addition to these two transporters. The family of voltage-activated Cl− channels (ClC; Jentsch et al. 1990; Thiemann et al. 1992) comprises nine isoforms, some of which are present in the neocortex. Most of these channels are located at endosomal or vesicular membranes (ClC3–7), and hence the predominant channel in plasma membranes is probably ClC2 (Jentsch et al. 2005). Reduced ClC2 expression has been implicated in causing depolarizing GABA responses in the hippocampus during development (Mladinic et al. 1999), yet the role of ClC isoforms in maintaining low [Cl−]i has not been definitively established. Finally, anion exchangers (AE) are expressed in the CNS (Havenga et al. 1994) but little is known about their role in Cl− homeostasis.

Together, at least five different pathways participate in Cl− movements across neuronal membranes in cortical neurones, namely the GABAA receptors, KCC2, NKCC1, AE and ClC2. The relative contribution of these pathways to the normal function of GABAergic inhibition is poorly understood in the rodent cortex let alone in the human neocortex. Detailed analysis of the components of Cl− homeostasis is hampered partly due to the lack of potent and selective pharmacological tools. For instance, furosemide, a widely used blocker of neuronal Cl− transport (Deisz & Lux, 1982; Misgeld et al. 1986; Thompson et al. 1988a; DeFazio et al. 2000; Williams & Payne, 2004), decreases K+-coupled Cl− outward transport and thus increases [Cl−]i (Deisz & Lux, 1982). However, furosemide also blocks AE of erythrocytes (Brazy & Gunn, 1976) and NKCC1 (see Russell, 2000 for review).

Mounting evidence indicates that the ionic gradient of inhibition is disturbed in human epileptogenic tissues. Depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated responses have been reported in neocortical (Deisz et al. 1998) and hippocampal tissues (Cohen et al. 2002; Huberfeld et al. 2007) obtained from epilepsy surgery. However, the mechanisms by which GABAA receptor-mediated responses are converted into depolarizations are controversial. In the neocortex, reductions of KCC2 (Deisz et al. 1998) or an up-regulation of NKCC1 (Palma et al. 2006) have been proposed, either of which may shift the balance between the two opposing directions of Cl− transport, thus possibly setting the EIPSP-A to more depolarized values.

We evaluated possible mechanisms contributing to altered Cl− homeostasis in human cortical neurones in epilepsy surgery tissue (HENC neurones). Parallel experiments were carried out in rat cortical neurones to establish the effects of several drugs on Cl− homeostasis, allowing us to estimate the relative contribution of various pathways to Cl− efflux from rat and HENC neurones.

Methods

Human and rat cortical tissue

The experiments were approved by the ethics committee of the Charité (30.9.1997) and all patients provided informed consent for use of their tissues in adherence with the Declaration of Helsinki. A total of 96 resections (43 female and 53 male patients) were investigated. On average, the patients were (means ±s.d.) 35.0 ± 13.8 years old and suffered epilepsy since the age of 15.0 ± 12.0 years, i.e. for 19.7 ± 13.6 years. Tissues from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE with or without ammon's horn sclerosis) consisting mainly of the frontal pole of the temporal lobe comprised the largest group of resections (70%). Epileptogenic tissues from other sites were less frequent (frontal lobe epilepsy 4%) and some tissues exhibited also various pathologies (tumour 10%, dysplasia 9%, lesion 7%). For brevity's sake, we refer to neurones from human epileptogenic tissues collectively as HENC neurones.

The procedures have been previously described (Deisz, 1999b; Teichgräber et al. 2009). In brief, human cortical tissue was collected in the operating theatre and transferred to the laboratory in a cold modified artificial cerebrospinal fluid (mACSF, see below). The tissue was cut into smaller blocks which were subsequently cut into slices (nominally 400 μm) with a vibratome (TPI 1000, St Louis, MO, USA or HM650V, Microm, Walldorf, Germany). The slices were stored at room temperature in beakers filled with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF, composition see below) equilibrated with 95% O2–5% CO2 until used.

Experiments on slices of rat sensorimotor cortex (Wistar, age 30–50 days) were made adhering to accepted guidelines regarding housing and handling of animals (see Deisz, 1999a). The experiments were registered at the responsible authority (Landesamt für Arbeitsschutz, Gesundheitsschutz und technische Sicherheit Berlin, T 0206/96). In brief, animals were anaesthetized with ether and decapitated with an animal guillotine. The relevant block of the brain was removed and slices were made using the same methods and maintained under identical conditions as the human tissue slices.

Solutions and drugs

For the transport of the tissue we used cold (about 5°C) mACSF containing (in mm): NaCl 70, KCl 2.5, NaH2PO4 1.25, MgSO4 2, CaCl2 0.5, NaHCO3 26, (+)-d-glucose 25 and sucrose 75, equilibrated with 95% O2–5% CO2, pH 7.4. For storage of the slices and recording we used a standard ACSF containing (in mm): NaCl 124, KCl 5, NaH2PO4 1.25, MgSO4 2, CaCl2 2, NaHCO3 26 and (+)-d-glucose 10, equilibrated with 95% O2–5% CO2, pH 7.4. These substances were of analytical grade (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The antagonists for the AMPA- and NMDA-type glutamate receptors, CNQX and d-APV (Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK or Ascent Scientific, Weston-Super-Mare, UK), were usually applied at 10 and 20 μm, respectively. In some cases the concentrations were increased to 20 and 50 μm. The ACSF containing these two antagonists will be referred to as CD-ACSF. In some experiments we also added 2 μm CGP 55845A ([3-[[(1S)-1-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)ethyl]amino]-2-(S)-hydroxypropyl](phenylmethyl)phosphinic acid hydrochloride), a potent GABAB receptor antagonist (kindly provided by Novartis, Basel, Switzerland), to the CD-ACSF, termed CDC-ACSF. We chose CGP 55845A because it antagonizes not only postsynaptic but also presynaptic GABAB receptors (Deisz, 1999a; Teichgräber et al. 2009), hence reducing the frequency-dependent depression of inhibition (Deisz & Prince, 1989). These drugs were added to the ACSF from aqueous stock solutions (stored at −20°C). Furosemide (200 μm) and bumetanide (10 μm or 50 μm; both Sigma, Taufkirchen, Germany) were added directly to the ACSF or CDC-ACSF. Stock solutions of the voltage-gated Cl− channel blocker 9-anthracene carboxylic acid (9AC; Clark et al. 1998) were made with DMSO. The maximal DMSO content in the ACSF was 0.1%.

Recording and stimulation

Individual slices were transferred to a submerged-type recording chamber and perfused with 95 % O2–5% CO2-equilibrated ACSF at about 5 ml min−1. Temperature was kept constant at 32°C with a temperature controller (SCTC-20E, npi, Tamm, Germany). Intracellular recordings were carried out in cortical layer II/III neurones with sharp microelectrodes. Neurones were selected if they had a resting membrane potential more negative than −60 mV, action potential (AP) amplitudes >70 mV and input resistances >10 MΩ. Only regularly firing neurones were included; burst-firing neurones (e.g. Deisz, 1996) were only rarely encountered. Pipettes were pulled from filamented borosilicate glass (1.2 mm o.d., 0.8 mm i.d, Hilgenberg, Malsfeld, Germany) with a Brown–Flaming pipette puller (P87, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA). Electrode resistances ranged from 80 to 100 MΩ when filled with potassium acetate (1 m KAc; Sigma, plus 1 mm KCl titrated to pH 7.2 with acetic acid). In experiments to alter the anion gradient, 1 m KCl (plus 10 mm Hepes titrated to 7.2 with KOH) or 1 m KNO3 filling solution was used to increase the intracellular anion concentration as previously described (Misgeld et al. 1986; Thompson et al. 1988a; Luhmann & Prince, 1991). Electrodes were connected to a current-clamp amplifier (SEC-10, npi). Data were digitized online with PC-based acquisition hardware and software (Digidata 1200 system and pCLAMP 9.2; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA; some early experiments were recorded with the preceding generation of hardware and software).

Bipolar stimulating electrodes (SNEX-200X, Science Products, Hofheim, Germany) positioned in layer I in the vicinity of the recorded neurone were used to elicit synaptic responses. We chose stimulation in layer I rather than layer VI because from this location IPSPs could be evoked before and after pharmacological isolation. Orthodromic stimuli (duration 100 μs, usually 0.2 Hz or below, unless stated otherwise) were delivered using an isolation unit (A.M.P.I., Jerusalem, Israel). All traces shown in the figures were subjected to digital filtering (800 Hz) and truncation of stimulus artefacts.

Families of current injections (steps from −0.5 nA to +0.7 nA, 0.05 nA increment, 600 ms, at 0.2 Hz) were applied to estimate neuronal input resistance, firing properties and AP amplitudes. A second family of current injections was applied with a concomitant orthodromic stimulus (usually 12 V) to evaluate voltage-dependent properties of synaptic potentials and to determine the EIPSP-A. To this end, the linear part of the amplitude–voltage relation was approximated by linear fit.

To ascertain the steady-state condition of the applied drugs, the time course of solution exchange was determined by evaluating the amplitudes of postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) (elicited at 0.1 or 0.05 Hz) during washing in CDC-ACSF. The gradual dwindling of the amplitude on application of CDC-ACSF was approximated by an exponential fit yielding a τ of decay of about 100 s. Thus, measurements commenced 10 min after the start of solution exchange when steady state had been attained.

To evaluate the time course of Cl− efflux, synaptic potentials were elicited at 0.2 or 0.33 Hz before, during and after iontophoretic injection of Cl− (0.5, 1 or 2 nA for 0.5 or 1 min). The amplitudes of IPSPA responses were measured from a window (12–18 ms, usually about 15 ms) after the stimulus (apparent time to peak of the IPSPA). A given time point was kept for all IPSPA measurements from a neurone, except after pharmacological isolation, then the peak at resting Em was taken. The decay of amplitude after cessation of iontophoresis was fitted by a single exponential function to determine the kinetics of recovery of IPSPA amplitudes. To reduce contamination of the IPSPA by temporally overlapping excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) and GABAB receptor-mediated IPSP (IPSPB), measurements were also carried out in CDC-ACSF. Since the IPSPA sometimes exhibited considerable fluctuation in amplitude, injections of anions were carried out in triplicate and the data were averaged from a given protocol to obtain a reliable time constant (τ) of IPSPA amplitude changes.

The time course of IPSPA changes is too fast (near 7 s; Thompson et al. 1988a,b; Luhmann & Prince, 1991) to be followed by repetitive determinations of EIPSP-A (30 s for 10 current injections with stimulation at 0.33 Hz). To estimate the changes in [Cl−]i, we used the following substitute: we determined the driving force of the IPSPA (Em–EIPSP-A) and expressed the amplitude as a percentage of the driving force. Assuming linearity between the amplitude and driving force, the peak IPSPA amplitude after cessation of iontophoresis was used to estimate the maximal EIPSP-A. From this, we calculated [Cl−]i using the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz equation assuming a permeability ratio Cl−:HCO3− of 1:0.2 (Kaila et al. 1993). We refrained from calculating ionic activities and give concentrations throughout.

Assuming first order kinetics, the IPSPA amplitude recovery was fitted by a single exponential function, the time constant (τ) obtained was used to calculate the rates of Cl− efflux (1/τ). The difference in rates before and during application of a drug provided an estimate of the transport rate by the affected pathway. With the drugs and experimental conditions employed, the rates of all pathways could be determined using the equations below. The total flux rate of Cl− extrusion (ϕ= 1/τ of recovery) is the sum of these four pathways:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

|

(5) |

Linear and non-linear fits to data points were carried out with Origin 7.1 software (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA). Statistical evaluation of the data was usually carried out with a statistics program (Statview, Abacus Concepts Inc., Berkeley, CA, USA), unless stated otherwise. Group differences were evaluated with Student's t test for paired or unpaired data as appropriate. To test for a normal distribution of data, or deviation thereof, we used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with Lilliefors's significance correction and the Shapiro–Wilk test (PASW statistics program, v. 18, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The number of observations given in the text represents the number of neurones under a particular condition. Since the recording of some neurones was discontinued, the number of observations of subsequent measurements differ. Not all of the various parameters (e.g. EIPSP-A with KCl-filled electrodes and recovery tau from Cl− loading) were determined in every neurone, and thus the number of observations of apparently related parameters does not match precisely. Statistical evaluation was, however, carried out on the corresponding pairs. P values <0.05 were considered to indicate significant differences. All values are given as means ±s.d. in the text. The vertical bars denote the s.e.m. in all figures.

Some of these data have previously been presented in abstract form (Deisz et al. 1998, 2008).

Results

Depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated responses

Synaptic responses in HENC neurones consisted of a large depolarization (Deisz, 1999b; Teichgräber et al. 2009) without the typical sequence of EPSPs and IPSPs observed in rodent cortex (Connors et al. 1988; Deisz & Prince, 1989; Kaila et al. 1993), i.e. the synaptic responses usually had no discernible IPSPA component at resting Em in standard ACSF (Fig. 1A). In some neurones the synaptic responses steeply increased with subtle increases in stimulus intensity, similar to pharmacologically induced paroxysmal depolarization shifts (PDSs) in rodent neocortex (Gutnick et al. 1982). However, the synaptic responses were, unlike PDSs, often devoid of APs. Therefore, we refer to these compound synaptic responses as depolarizing shifts (DSs). On the other hand, the voltage dependence of these DSs was similar to PDSs, i.e. the membrane potential at the peak of the synaptic response attained almost the same voltage from every potential from which it was elicited, indicating a state of high conductance.

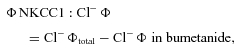

Figure 1. Properties of synaptic responses in HENC neurons.

A, voltage traces at various membrane potentials induced by current injection. Orthodromic stimulation (12 V) elicits a fairly large depolarization in control conditions (current injections −0.5 n A to +0.5 nA, 0.1 nA increments; Em: −72.4 mV; KAc-filled microelectrode). B, traces from the same neurone as shown in A in the presence of CDC-ACSF, revealing an obvious IPSPA in the top trace (time-to-peak of ∼25 ms post-stimulus, Em−72.0 mV, stimulus intensity 12 V). The time of stimulation is obvious from the blanked stimulus artefact here and throughout the figures. C, determination of the EIPSP-A reveals a value of −53.8 mV in control and −59.5 mV in the presence of CDC-ACSF. D, histogram of EIPSP-A values obtained in HENC neurones in the presence of CDC-ACSF. Note the multiple peaks suggesting an inhomogeneous distribution. E and F, traces of synaptic responses obtained at resting Em in CDC-ACSF and during addition of 50 μm bicuculline (Bic) as indicated. The incomplete blockade may have been due to excess GABA.

The extrapolated reversal potential of the compound synaptic response (near 15 ms) was a mean of −54.0 ± 10.0 mV (n = 92), considerably less negative than in rodent cortical neurones (e.g. Kaila et al. 1993). This might be due either to a relative increase in EPSP or alterations in IPSPA. In the presence of CDC-ACSF or CD-ACSF, this reversal potential shifted towards more negative values (Fig. 1C), yet a depolarizing component remained in HENC neurones (EIPSP-A: −61.5 ± 8.1 mV; n = 50; P < 0.001 vs. ACSF) with an unaltered resting membrane potential (Em; ACSF: −71.5 ± 4.6 mV, CD-ACSF or CDC-ACSF: −71.4 ± 4.9 mV; P > 0.05). The EIPSP-A values obtained in CD-ACSF and CDC-ACSF were indistinguishable (P > 0.05) and therefore pooled. We considered the possibility of an insufficient block of excitatory amino acid receptors and increased the concentrations of CNQX and d-APV up to 20 and 50 μm in some experiments, but depolarization with a reversal potential near −60 mV persisted. Application of bicuculline at 20 μm reduced the depolarization remaining in CDC-ACSF by about 50% (n = 1) and at 50 μm by 85% (n = 7, P < 0.001), indicating the presence of depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated responses (Fig. 1E and F).

The fairly large s.d. of the reversal potentials in HENC neurones (8.1 mV) indicates a non-homogeneous distribution. The histogram of the data (see Fig. 1D) shows at least two distinct peaks in the distribution of the EIPSP-A. Therefore, EIPSP-A values were segregated into two groups using the mean value plus 2 s.d. of rat neurones as the border (−64.2 mV, see below). Of 50 neurones evaluated, 23 exhibited an EIPSP-A more negative than −64 mV averaging −68.8 ± 2.3 mV. This value is indistinguishable from that of rat neurones (P > 0.5) and close to established data from rodent neurones (e.g. Connors et al. 1988). The other group exhibited a less negative EIPSP-A, on average −55.2 ± 5.7 mV (n = 27; P < 0.0001 vs. the other group), indicating a dysfunction of Cl− homeostasis in about half of the HENC neurones. To verify this difference statistically, we used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with Lilliefors's significance correction and the Shapiro–Wilk test, both indicating significant differences between the two subpopulations (P = 0.017 and P = 0.009, respectively).

Kinetics of Cl− transients

To delineate the mechanisms contributing to the depolarizing shift in EIPSP-A, we evaluated the properties of Cl− outward transport using anion injection (Llinás et al. 1974; Thompson et al. 1988a,b;) and a variety of bath-applied drugs. Before describing the kinetics of Cl− transients in HENC neurones, we present parallel experiments on rat cortical neurones corroborating and extending previous data from guinea pig cortex under our experimental conditions (Thompson et al. 1988a,b;). Furthermore, we compared EIPSP-A measurements using KAc-filled microelectrodes and KCl-filled microelectrodes, to estimate Cl− regulation under steady-state conditions.

Kinetics of Cl− transport in rat cortical neurones

Recordings from rat cortical neurones with KAc-filled microelectrodes yielded an apparent mean EIPSP-A of −65.5 ± 3.1 mV (n = 47) in ACSF and −69.3 ± 2.5 mV in CDC-ACSF (n = 16, P < 0.001 vs. ACSF. Em was essentially the same in both conditions (control: −72.7 ± 3.7 mV, n = 47; CDC-ACSF: −71.9 ± 3.0 mV, n = 16; P > 0.05). Recordings from rat cortical neurones with KCl-filled microelectrodes usually caused a fairly rapid shift of the IPSPA (within a few minutes of impalement), merging with the preceding EPSP. The apparent mean EIPSP-A was −56.2 ± 6.4 mV (n = 79), less negative compared to data obtained with KAc-filled microelectrodes (P < 0.0001). Pharmacological isolation of the IPSPA by applying CDC-ACSF caused a significant shift of the EIPSP-A, to a mean −61.4 ± 4.9 mV (n = 47). This corresponds to a [Cl−]i of 10.2 mm compared with 6.7 mm when recorded in the same condition with KAc-filled electrodes (P < 0.001). This indicates that (i) the apparent EIPSP-A of rat cortical neurones is ‘contaminated’ by some overlap with the preceding EPSP and (ii) the steady-state elevation of [Cl−]i by leakage from the electrode shifts the EIPSP-A to values near −60 mV, corresponding to an increase of [Cl]i from 6.7 mm to 10.2 mm.

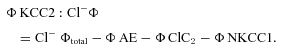

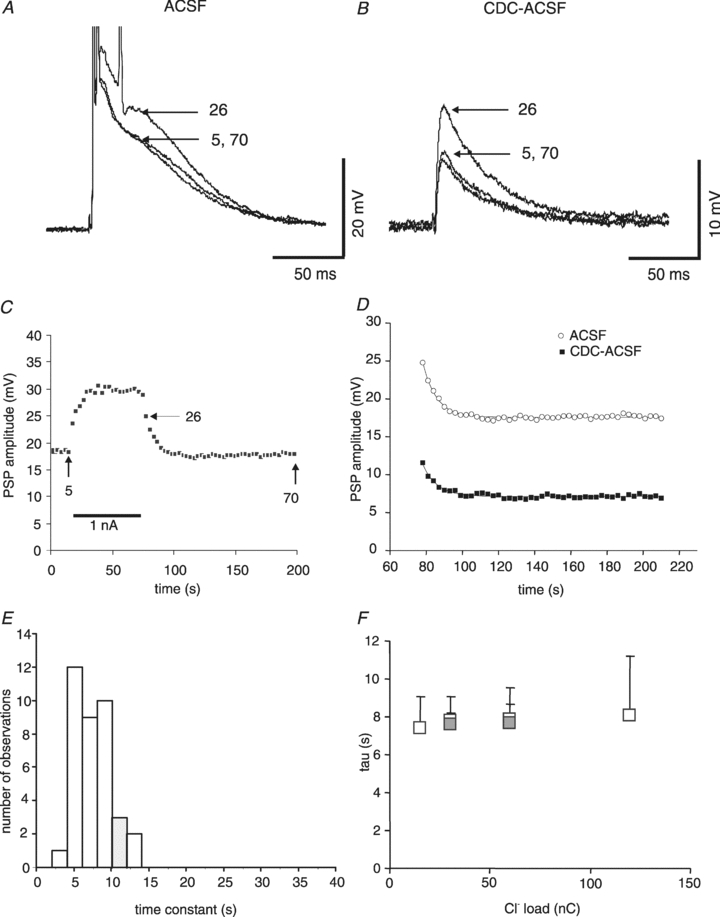

Current injection (1 nA, 1 min) caused a further increase in the amplitude of IPSPA near 15 ms post-stimulus, recovering with a τ of 7.9 ± 2.7 s (n = 84) to the preceding control value (Fig. 2A, C and D). The recovery τ exhibited no obvious dependence on the magnitude of the preceding Cl− load (Fig. 2F), averaging 7.4 ± 2.3 s (n = 11) after small current injections (0.5 nA for 30 s), and 8.0 ± 3.5 s after large current injections (2 nA for 1 min; n = 16; P > 0.05). This similar recovery of IPSPA from different loads allowed averaging per neurone, yielding a mean τ of 7.9 ± 2.4 s (n = 84).

Figure 2. Time course of IPSPA changes in rat cortical neurones during and after cessation of current injection from a KCl-filled microelectrode.

A, traces in ACSF (Em−73. mV) before current injection (sample 5), after end of current injection (sample 26) and after recovery (sample 70). The arrows indicate the point of measurement. B, corresponding traces from the same neurone shown in A in the presence of CDC-ACSF (Em−71.0 mV). C, plot of the compound PSP amplitudes before, during and after Cl− injection. The arrows indicate the times of the recordings illustrated in panel A. Three consecutive injections from the neurone shown in A have been averaged. Note the instantaneous increase in amplitude due to the step hyperpolarization induced by current injection. D, determination of the time constant of IPSPA amplitude recovery. Applying exponential fits to the data points revealed tau values of 7.5 s in control ACSF (open symbols) and 7.9 s in CDC-ACSF (filled symbols). E, histogram of the tau values of IPSPA recovery in rat neurones in the presence of CDC-ACSF, indicating a fairly homogeneous distribution. F, plot of the time constant of recovery from various Cl− loads. The amount of injected Cl− has been plotted as charge (nA × time). The open symbols represent data obtained with injections of 15 nC (n = 11), 30 nC (n = 22), 60 nC (n = 84) and 120 nC (n = 16). The filled symbols represent data obtained with the same charge applied with different parameters (30 nC by 0.5 nA for 60 s (n = 11) and 60 nC by 2 nA 30 s (n = 22)).

This τ of recovery may be inaccurate due to alterations in the partly overlapping EPSP, e.g. through the recruiting of voltage-dependent conductances (Deisz et al. 1991) or a frequency-dependent depression of IPSPs (Deisz & Prince, 1989). The latter effect may occur at the higher stimulus frequencies necessary to obtain a reliable resolution of the time course. We therefore evaluated the recovery τ of isolated IPSPA in CDC-ACSF. The time courses in ACSF and in CDC-ACSF were similar (Fig. 2D). Injections of 1 nA (1 min) yielded a τ of 7.2 ± 2.5 s (n = 47) and 8.9 ± 3.7 s (n = 12) after large current injection (2 nA, 1 min; P > 0.05), indicating no effect of Cl− load on the time course of recovery. The τ values of recovery of the IPSPA amplitude from iontophoretic injections was of a mean 7.2 ± 2.4 s (n = 47), similar to measurements in ACSF (P > 0.05). The narrow distribution of time constants (Fig. 2E) indicates that the kinetics of Cl− transport are fairly homogeneous in the population of rat neurones investigated.

To estimate the changes in [Cl−]i induced by current injection, we calculated the EIPSP-A and thence [Cl−]i from the IPSPA amplitude after cessation of current injection (see Methods). Injection of 1 nA for 1 min increased [Cl−]i from 9.8 ± 2.8 mm to 14.3 ± 5.0 mm (n = 20, P < 0.0001), i.e. by 4.5 mm. In a subset of these neurones, injections of 1 nA for 1 min increased [Cl−]i from 8.5 ± 2. 9 mm to 11.4 ± 3.8 mm (n = 5; P < 0.01), i.e. by 2.9 mm, and injections of 2 nA for 1 min increased [Cl−]i to 15.3 ± 5.6 mm, i.e. by 6.8 mm (n = 5; P < 0.05 vs. 1 nA). The recovery τ was unaltered, averaging 6.3 and 6.5 s for 1 nA and 2 nA, respectively, despite an approximately twofold greater increase of [Cl−]i.

Pharmacology of Cl− transport in rat cortical neurones

To evaluate the contribution of individual Cl− routes, we investigated the effects of selected blockers on steady-state values of EIPSP-A and on the kinetics of Cl− extrusion.

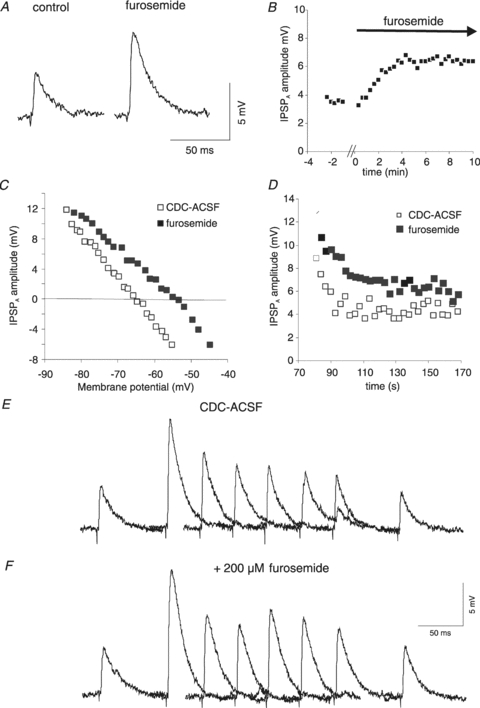

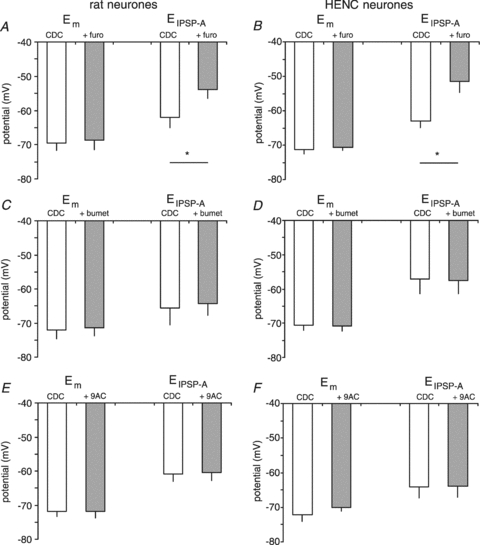

Application of furosemide (200 μm) tended to increase the isolated IPSPA amplitude from 3.3 ± 1.7 mV to 6.4 ± 5.6 mV (see Fig. 3A; n = 7; P = 0.052). The mean tau of increase in amplitude (100.2 s; see Fig. 3B) was close to the tau of CDC-ACSF effects on PSPs in these neurones (91.7 s), indicating that furosemide took effect quickly. Application of furosemide shifted the EIPSP-A from −62.9 ± 5.8 mV to −55.4 ± 5.4 mV (n = 6, P < 0.05; Figs 3C and 4A), corresponding to a mean increase of [Cl−]i from 9.7 mm to 13.9 mm (n = 5, P < 0.05). The Em was unaltered (P > 0.05, see Fig. 4A). Furosemide increased the τ of IPSPA recovery from 7.1 ± 3.0 s to 16.6 ± 6.7 s (n = 8, P < 0.01; Fig. 3D–F), close to published data from guinea-pig cortex (15.9 s; Thompson et al. 1988a). The maximal [Cl−]i attained after cessation of current injection (1 nA, 1 min) averaged 13.1 ± 4.3 mm in CDC-ACSF and 20.3 ± 6.5 mm in the presence of furosemide. The increases of [Cl−]i in CDC-ACSF (4.3 ± 2.9 mm) and furosemide (7.0 ± 4.8 mm) were similar (n = 5; P > 0.05). During washout of furosemide, the IPSPA amplitude gradually decreased (from 8.5 to 4.8 mV; tau 258 s, n = 3) and the τ of IPSPA recovery from Cl− loading returned towards control values (9.3 ± 5.4 s, n = 3, P < 0.05 vs. furosemide and P > 0.5 vs. preceding control).

Figure 3. Effects of furosemide on rat cortical neurones.

A, two traces of pharmacologically isolated IPSPA in control and in the presence of furosemide (200 μm). The approximately twofold increase in IPSPA amplitude (from 4.6 mV to 7.6 mV) in this neurone corresponds to the average increase in driving force from 7.4 ± 2.2 mV to 14.8 ± 4.8 mV. All data illustrated in this figure were obtained with KCl-filled microelectodes. B, plot of the average amplitude of the isolated IPSPA during the washing in of furosemide (200 μm). The gap of data points represents about 1 min, required for the furosemide-containing CDC-ACSF to reach the chamber. C, plot of the IPSPA amplitudes vs. Em varied by incremental current injection (from −0.5 nA to +0.6 nA). A linear regression of the data points (not shown) revealed a shift of the EIPSP-A from −65.2 mV to −55.2 mV. D, plot of the IPSPA amplitude following cessation of current injection from the records shown in panels E and F. The exponential fit to the data points (not shown) yields 7 s in control and 13 s in the presence of furosemide. E, traces of the isolated IPSPA before and after current injection. The samples shown were obtained before current injection and 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21 and 130 s after the end of current injection. The scale of the panels E and F refers only to the individual traces. The traces have been partly superimposed. F, traces corresponding to those of panel E from the same neurone obtained in the presence of 200 μm furosemide. A bar graph summarizing these data is shown in Fig. 11D to facilitate comparison with the data obtained in HENC neurones.

Figure 4. Effects of various antagonists on Em and EIPSP-A in rat and HENC neurones.

Plot of Em and EIPSP-A obtained with KCl-filled microelectrodes in CDC-ACSF-containing furosemide (furo), bumetanide (bumet) or 9AC as indicated. Panels A, C and E summarize the effects of antagonists on Em and EIPSP-A in rat neocortical neurones as indicated. Panels B, D and F summarize the effects of antagonists on Em and EIPSP-A in HENC neurones as indicated.

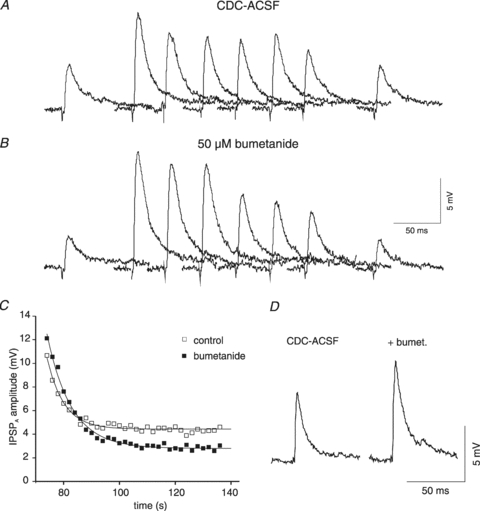

Application of 10 or 50 μm bumetanide, a selective blocker of NKCC, increased the amplitude of the isolated IPSPA during the first 10 min from 3.9 ± 1.6 mV to 6.2 ± 4.9 mV (Fig. 5D; n = 11, P < 0.05). However, in a subset of these neurones, bumetanide had no effect on the EIPSP-A (CDC-ACSF: −62.8 ± 7.2 mV, bumetanide: −61.5 ± 5.4 mV; n = 5; P > 0.5; Fig. 4C), corresponding to a [Cl−]i of 9.9 ± 3.3 mm and 10.3 ± 2.7 mm. The recovery τ of IPSPA after cessation of Cl− injection increased from 7.0 ± 1.7 s to 8.6 ± 1.6 s (n = 12, P < 0.001; see Fig. 5A–C and Fig. 10D). The effects of 10 μm and 50 μm bumetanide (n = 6 each) were similar (P > 0.05) and therefore we pooled the data. On washout of bumetanide, the τ of recovery from Cl− loading returned to control values (6.9 ± 1.7 s, n = 6). The maximal [Cl−]i after cessation of the current injections averaged 15.6 ± 7.1 mm and 21.3 ± 6.0 mm (n = 5; P < 0.05) in CDC-ACSF and during addition of bumetanide, respectively. Thus, the injection increased [Cl−]i on average by 5.9 ± 4.8 mm in control and 10.9 ± 4.3 mm in the presence of bumetanide (n = 5; P < 0.05). The significant slowing of recovery together with unaltered EIPSP-A by bumetanide (see Fig. 4C) suggests that NKCC1 plays a minor role in the maintenance of steady state [Cl−]i in healthy cortical neurones, but is operating at elevated [Cl−]i. In addition, it would appear to impede Cl− loading via iontophoresis, as indicated by the much larger increase of [Cl−]i in the presence of bumetanide.

Figure 5. Effects of bumetanide on rat neurones.

A, traces of isolated IPSPA before and after current injection from a KCl-filled microelectrode. The samples shown were obtained in CDC-ACSF before current injection and 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 60 s after the end of current injection (2 nA, 1 min). B, traces from the same neurone as shown in A in the presence of 50 μm bumetanide corresponding to traces shown in panel A. C, plot of the IPSPA amplitude following cessation of current injection in CDC-ACSF (open squares) and after addition of 50 μm bumetanide (filled squares). The symbols represent the average values of three consecutive injections. The curves represent a single exponential fit with tau values of 6.0 s (CDC-ACSF) and 8.7 s (bumetanide). The average time constants have been plotted together with data from HENC neurones (see Fig. 10D). D, traces of the isolated IPSPA from a rat cortical neurone in CDC-ACSF and after 10 min of bumetanide application.

Figure 10. Effects of bumetanide on HENC neurones.

A, sample traces of isolated IPSPA before and after Cl− injection. The traces shown were obtained in CDC-ACSF before current injection and 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 150 s after the end of current injection (2 nA, 1 min). B, sample traces from the same neurone as shown in A in the presence of 50 μm bumetanide corresponding to traces shown in A. C, plot of the IPSPA amplitude following cessation of Cl− injection in CDC-ACSF (open squares) and during addition of 50 μm bumetanide (filled squares). The symbols represent the average of three consecutive injections. The curves represent single exponential fits with time constants of 17.4 s (CDC-ACSF) and 26.4 s (bumetanide). D, mean τ values in CDC-ACSF and after addition of bumetanide in rat and HENC neurones. Bumetanide was applied at both 10 and 50 μm but its effect was not increased at the higher concentration and therefore the data have been pooled.

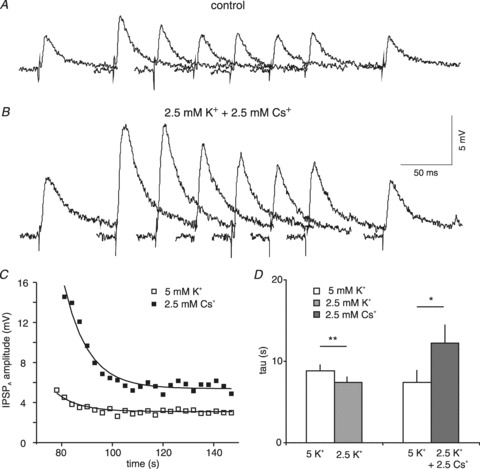

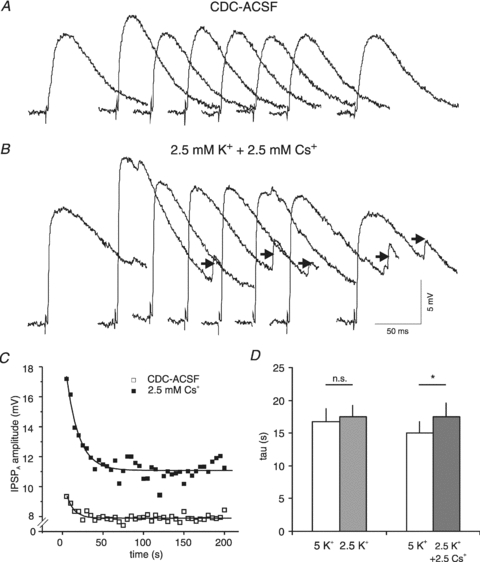

We then tested for involvement of a K+-dependent Cl− extrusion by evaluating the effects of reduced [K+]o on the kinetics of recovery from Cl− loading. Reducing [K+]o by half (equimolar replacement by 2.5 mm Na+; both ACSFs containing the CDC additions) reduced the τ of IPSPA recovery from 8.9 ± 2.3 s to 7.4 ± 2.3 s (n = 13, P < 0.01; Fig. 6D). The reduction of [K+]o also caused a hyperpolarizing shift in the EIPSP-A from −59.3 ± 1.4 mV to −66.2 ± 5.5 mV (n = 3). The acceleration of recovery and shift of EIPSP-A confirmed that the K+ gradient affects the rate of Cl− extrusion and steady-state level of [Cl−]i in rat cortical neurones. A further test of the involvement of K+-coupled transporters was made by evaluating the effects of Cs+, known to have an impact on Cl− homeostasis (Aickin et al. 1982; Kakazu et al. 1999; Williams & Payne, 2004). Replacing half of [K+]o with 2.5 mm Cs+ caused a marked increase in the recovery τ (Fig. 6A–C), from 7.1 ± 3.0 s to 12.2 ± 4.5 s (n = 5, P < 0.05 vs. 5 mm K+, Fig. 6D).

Figure 6. Effects of Cs+ on IPSPA recovery in rat neurones.

A, traces of isolated IPSPA before and after current injection from a KCl-filled microelectrode. The samples shown were obtained in 5 mm K+ CDC-ACSF before current injection and 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21 and 130 s after the end of current injection. B, traces from the same neurone as shown in A in the presence of 2.5 mm K+ and 2.5 mm Cs+ CDC-ACSF corresponding to the traces shown in panel A. The scale in panel B refers only to the individual traces in panels A and B. Traces have been partly superimposed. C, plot of the average IPSPA amplitude following cessation of current injection from the recordings shown in panel A and B. The exponential fit to the data points yields a tau of 6.1 s in 5 mm K+ CDC-ACSF (open symbols) and 9.5 s in the presence of 2.5 mm K+ and 2.5 mm Cs+ (filled symbols). D, plot of the mean IPSPA time course on reducing [K+]o from 5 mm to 2.5 mm and replacing 2.5 mm K+ with 2.5 mm Cs+ as indicated.

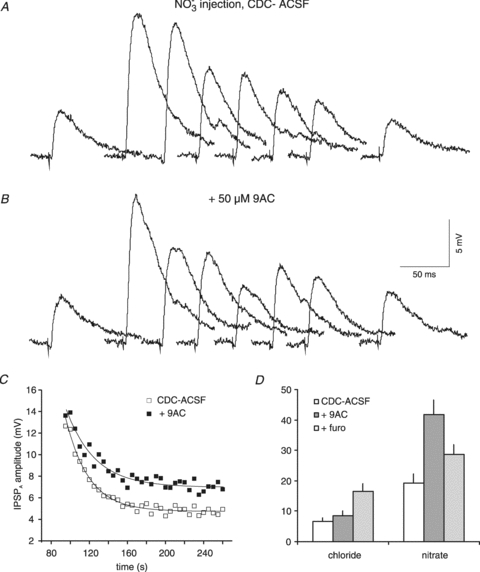

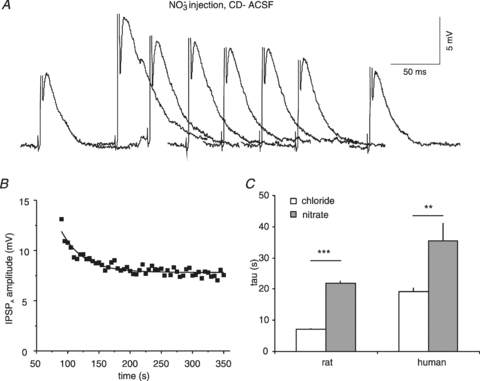

To estimate the contribution of other Cl− pathways, namely Cl−/HCO3− exchangers (the AE gene family; Havenga et al. 1994) and ClC2 (see Fahlke, 2001), we determined the kinetics of recovery of IPSPA amplitudes following NO3− injections. We chose NO3− because it is permeant through the GABAA receptors (Bormann et al. 1987), yet is extruded much more slowly than Cl− (Thompson et al. 1988b). Following NO3− injection, the amplitudes of IPSPA recovered fairly slowly to preceding control values (Fig. 7A–D). In control ACSF the compound synaptic potentials recovered with a τ of 20.5 ± 9.9 s (n = 19, P < 0.0001 vs. Cl− injection in ACSF). Similar values were obtained in CDC-ACSF, where the τ averaged 21.1 ± 6.1 s (n = 17, P > 0.05 vs. ACSF; P < 0.0001 vs. Cl− injection in CDC-ACSF). To test whether the NO3− (i.e. unselective) pathway involves AE, we applied furosemide. Bath application of furosemide (200 μm in CDC-ACSF) considerably increased the recovery τ of IPSPA following NO3− injections to 28.6 ± 4.6 s (n = 3).

Figure 7. Effects of NO3− injection into rat neurones.

A, traces of isolated IPSPA before and after NO3− injection. The samples shown were obtained in CDC-ACSF before current injection and 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 300 s after the end of current injection (1 nA, 1 min). B, traces from the same neurone as shown in A in the presence of 50 μm 9AC, corresponding to traces shown in panel A. C, plot of the IPSPA amplitude following cessation of current injection in CDC-ACSF (open squares) and after addition of 50 μm 9AC (filled squares). The symbols represent the average values of three consecutive injections. The curves represent single exponential fits to the data with tau values of 24.1 s (CDC-ACSF) and 30.3 s (9AC). D, plot of the mean τ values following Cl− and NO3− injections in CDC-ACSF (open columns), in the presence of 50 μm 9AC (dark grey columns) and in the presence of 200 μm furosemide (light grey columns). The CDC-ACSF values given are from the 9AC series of measurements.

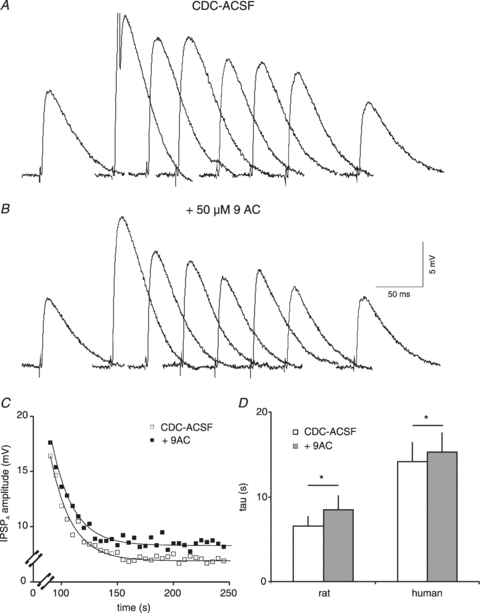

Finally, we considered the participation of voltage-activated Cl− channels in the efflux of [Cl−]i by evaluating the effects of 9AC, a blocker of ClC2 (Clark et al. 1998). Application of 9AC (50 μm) had no effect on the amplitude of isolated IPSPA (control: 4.0 ± 2.3 mV; 10 min 9AC: 3.0 mV ± 1.7 mV; n = 6, P > 0.5). In the presence of 9AC, the recovery τ increased from 6.6 ± 2.7 s to 8.4 ± 4.2 s (n = 7; Fig. 8A–C; P < 0.05; 6 neurones in CDC-ACSF, 1 in ACSF) and returned to control values after washout (5.9 ± 1.0 s, n = 4). The EIPSP-A was unaltered by 9AC (CDC-ACSF: −60.8 ± 4.9 mV, CDC-ACSF plus 9AC: −60.5 ± 5.0 mV; n = 6, P > 0.5; see Fig. 4E), despite the significant slowing of recovery by 9AC (Fig. 8). The [Cl−]i averaged 11.9 ± 1.2 mm and 11.2 ± 1.5 mm in CDC-ACSF and 9AC, respectively (n = 5, P > 0.05). Interestingly, Cl− injection (1 nA, 1 min) increased [Cl−]i to 16.9 ± 3.4 mm in CDC-ACSF and to 21.7 ± 9.2 mm in the presence of 9AC. Thus [Cl−]i increased by 5.0 mm in control and by 10.5 mm in the presence of 9AC (n = 5; P = 0.059). The larger increase of [Cl−]i by current injection might indicate that 9AC-sensitive pathways were active during current injection, impeding an effective Cl− loading. To test whether 9AC indeed affects an unselective pathway of Cl− extrusion, we also applied 9AC to neurones recorded with KNO3-filled electrodes (Fig. 7A, B). Application of 9AC increased the τ of recovery from NO3− loading from 19.3 ± 5.2 s to 41.7 ± 8.5 s (n = 4, P < 0.05: Fig. 7C and D), indicating that 9AC reduced a relatively unselective, NO3−-carrying pathway in cortical neurones.

Figure 8. Effects of 9AC on rat cortical neurones.

A, traces of isolated IPSPA before and after Cl− injection. The samples shown were obtained in CDC-ACSF before current injection and 0, 3, 6, 9, 8, 12 and 60 s after the end of current injection (1 nA, 1 min). B, traces from the same neurone as shown in A in the presence of 50 μm 9AC, corresponding to the traces shown in panel A. C, plot of the IPSPA amplitude following cessation of Cl− injection in CDC-ACSF (open squares) and after addition of 50 μm 9AC (filled squares). The symbols represent the average values of three consecutive injections. The curves represent a single exponential fit with time constants of 3.1 s (CDC-ACSF) and 4.6 s (9AC).

Taken together, these data indicate that all of the established Cl− pathways join forces to extrude Cl−, yet bumetanide and 9AC have marginal effects on the steady state reversal potential.

Rates of Cl− efflux via the various transport routes

The relative contribution of efflux pathways to the kinetics of Cl− extrusion appears to vary, judging from the distinct increases in τ induced by the various experimental manipulations. To test this possibility, we estimated the individual rates of Cl− efflux using eqns (1)–(5) (see Methods). The data are given in Table 1. The flux rate mediated by NKCC1 can be estimated from eqn (2) as the difference in Cl− flux rates obtained with and without bumetanide (0.0263 s−1). The Cl− flux mediated by ClC2 (eqn (3)) can be estimated as the rate difference between control and in the presence of 9AC (0.0336 s−1). Application of 9AC to neurones recorded with KNO3-filled electrodes yielded a slightly smaller rate for NO3− (0.0278 s−1), indicating that ClC2 has an apparent permeability ratio for Cl−:NO3− of 0.83. Assuming that AE and ClC2 represent relatively unselective pathways carrying Cl− and NO3−, the flux rate mediated by the AE can be calculated from the rate of NO3− extrusion (0.0475 s−1) minus the NO3− rate mediated by ClC2 (0.0278 s−1), i.e. 0.0197 s−1. The rate obtained from the NO3− extrusion, in turn, provides a rate for the more selective pathways, presumably KCC2 and NKCC1 (total rate of 0.1456 s−1 minus the rate mediated by unselective pathways of 0.0475 s−1), i.e. 0.0981 s−1. Finally, the rate mediated by KCC2 can be calculated from the rate in CDC-ACSF minus the rates mediated by NKCC1 (0.0263 s−1), AE (0.0197 s−1) and ClC2 (0.0336 s−1), yielding 0.0659 s−1. The reliability of these admittedly simplistic estimates will be detailed in the Discussion. Overall, we propose that the relative contribution of the pathways to the total flux in healthy cortical neurones is as follows: KCC2 45.3%, NKCC1 18.1%, AE 13.6% and ClC2 23.1%.

Table 1.

Time constants of recovery of rat neurones under the different experimental condition

| Condition | τ (s) | Rate (s−1) | Isol. rates (s−1) | Calculation of rates for the different pathways | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACSF | 7.85 ± 2.41 (84) | 0.1273 | |||||

| CDC-ACSF | 6.87 ± 2.36 (44) | 0.1456 | 0.1456 | ||||

| CDC-ACSF | 7.01 ± 1.67 (12) | 0.1426 | |||||

| With bumet. | 8.60 ± 1.61 (12) | 0.1163 | 0.0263 | 0.0263 | −0.0263 | ||

| CDC-ACSF | 7.12 ± 2.97 (8) | 0.1405 | |||||

| With furosemide | 16.57 ± 6.69 (8) | 0.0603 | 0.0801 | ||||

| CDC-ACSF | 6.58 ± 2.72 (7) | 0.1521 | |||||

| With 9AC | 8.44 ± 4.16 (7) | 0.1185 | 0.0336 | 0.0336 | −0.0336 | ||

| CDC-5 mm K+ | 7.13 ± 2.95 (5) | 0.1402 | |||||

| CDC-2.5 mm Cs+ | 12.23 ± 4.45 (5) | 0.0818 | 0.0584 | ||||

| CDC/nitrate | 21.06 ± 6.06 (17) | 0.0475 | 0.0475 | 0.0475 | |||

| With furosemide | 28.60 ± 4.56 (3) | 0.0350 | |||||

| CDC/nitrate | 19.32 ± 5.22 (4) | 0.0518 | |||||

| With 9AC | 41.68 ± 8.49 (4) | 0.0240 | 0.0278 | −0.0278 | −0.0197 | ||

| rate: | 0.0263 | 0.0336 | 0.0197 | 0.0659 | |||

| pathway: | NKCC1 | ClC2 | AE | KCC2 | |||

The time constants in control CDC-ACSF differ in some of the subgroups from the ensemble average. The rates were therefore calculated for each experimental group as difference in rate with and without the drugs. On the right hand the calculation of the rates of the individual pathways is presented. From the different rates obtained with 9AC for Cl− and NO3− extrusions, a relative permeability of ClC2 of Cl−vs. NO3− was calculated (0.83). Note that three neurones were not included in the average of the CDC-ACSF group, because the values were considered outliers (above the mean +2 s.d.).

Cl− extrusion in HENC neurones

With the same experimental conditions, we evaluated the kinetics of Cl− transport in HENC neurones. Recordings with KCl-filled microelectrodes revealed only small changes in synaptic potentials following neurone impalement. In fact, the synaptic responses obtained with KCl-filled electrodes looked, at first glance, fairly similar to those obtained with KAc-filled electrodes. Determination of the apparent EIPSP-A yielded an average of −48.8 ± 8.1 mV in ACSF (n = 87) and −59.7 ± 7.8 mV in CDC-ACSF (n = 53, P < 0.0001 vs. ACSF), the latter value corresponding to a [Cl−]i of 11.2 mm. The EIPSP-A obtained with KCl-filled electrodes in CDC-ACSF were similar to those obtained with KAc-filled electrodes (P > 0.05). Resting Em was, on average, indistinguishable between the two recording conditions and solutions (∼−71 mV).

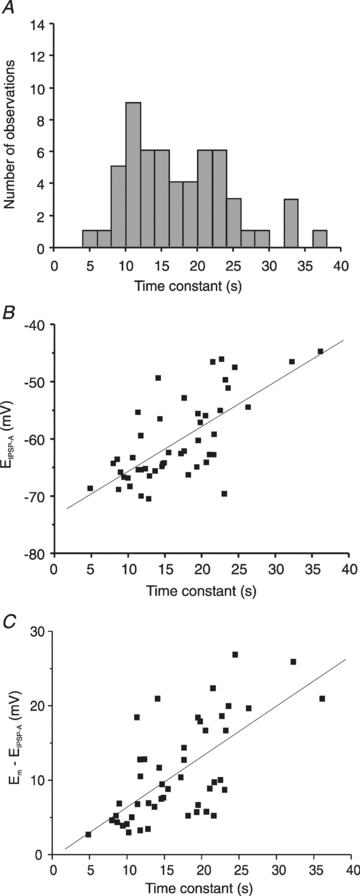

In ACSF, the injection of Cl− caused a further increase in the apparent IPSPA amplitude (near 15 ms post-stimulus), which slowly returned to the preceding control value. The recovery τ following injections of different amounts of Cl− was similar, small and large Cl− loads (e.g. 1 nA, 30 s vs. 2 nA 1 min) yielded τ values of 17.9 ± 10.2 s (n = 11) and 19.4 ± 9.2 s, respectively (n = 22; P > 0.05). Therefore, the values of different injections were averaged for each neurone, and on average a τ of 20.3 ± 11.4 s (n = 85) was obtained. The recovery τ exhibited a marked variability in a given tissue. Both fast recoveries (<11.5 s, mean τ of rat neurones +2 s.d.) and slow recoveries (>11.5 s) were obtained in 14 of 29 resections with more than one recorded neurone in control conditions. The variability of recovery τ values persisted in the presence of CDC-ACSF (see Fig. 9A) and on average the IPSPA recovered with a tau of 19.0 ± 9.6 s (n = 62, P > 0.5 vs. ACSF). It should be pointed out that the mean τ of all rat neurones was 7.2 ± 2.4 s in CDC-ACSF, and only three neurones exhibited τ values larger than 11.5 s (i.e. outliers above the mean +2 s.d.). In the human tissues only 12 of 62 neurones were below this border (average 9.3 ± 1.8 s), i.e. the majority of neurones exhibited a considerably slower Cl− extrusion (average 21.4 ± 9.3 s, n = 50; P < 0.0001). To test whether this large scatter of data represents statistically significant deviation from a normal distribution we used the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test with Lilliefors's significance correction and the Shapiro–Wilk test, both indicating significant differences (P = 0.038 and P = 0.000, respectively).

Figure 9. Parameters of inhibition in HENC neurones.

A, histogram of IPSPA recovery time constant of HENC neurones. Three neurones with time constants exceeding 40 s (42.4 s, 48.0 s and 54.3 s) are not shown in the graph to maintain the scaling of Fig. 2E. The plot reveals that 16 neurones had τ values <12 s, 20 neurones had τ values between 12 and 20 s, and the τ of 24 neurones was >20 s. B, plot of the EIPSP-Avs. the τ of IPSPA recovery following Cl− injection. C, plot of the driving force (Em–EIPSP) of neurones from HENC neurones recorded with KCl-filled microelectrodes vs. the time constant of IPSPA recovery.

To test whether the variability of tau values relates to the dichotomy of EIPSP-A in HENC neurones, we compared the reversal potentials of neurones with relatively small and large time constants. To this end, the reversal potentials of 48 neurones were segregated into two groups according to the above border of τ (11.5 s). Neurones with time constants below this border had an average τ of 9.3 ± 1.9 s (n = 11) and a mean EIPSP-A of −64.1 ± 4.5 mV (n = 11), indistinguishable from rat neurones recorded with KCl electrodes (P > 0.05). The remaining neurones clearly had a larger τ (19.5 ± 6.0 s) and exhibited a less negative EIPSP-A (average −58.9 ± 7.5 mV; n = 37, P < 0.05 vs. neurones with small τ), as was obvious from the approximately linear relation (see Fig. 9B). This indicates that less negative reversal potentials and increases in the depolarizing driving force of IPSPA are related to the large tau (Fig. 9C).

In CDC-ACSF, we calculated the changes in EIPSP-A and [Cl−]i induced by current injections (see Methods). Applying 1 nA for 1 min increased [Cl−]i from 11.8 ± 4.5 mm to 19.8 ± 8.3 mm (n = 23, P < 0.0001) after current injection, i.e. by 7.9 ± 4.5 mm. This is a significantly larger increase than under the same conditions in rat neurones (P < 0.01). In a subset of these neurones (Em: −71.3 ± 2.1 mV, EIPSP-A: −57.6 ± 7.3 mV), we compared the effects of different current injection magnitudes. Injection of 1 nA for 1 min shifted EIPSP-A to −45.3 ± 9.3 mV, indicating an increase of [Cl−]i to 22.8 ± 9.3 mm (n = 6, P < 0.05 vs. baseline for both). Injection of 2 nA for 1 min shifted EIPSP-A to −36.4 ± 14.7 mV, indicating an increase of [Cl−]i to 35.7 ± 18.8 mm (n = 6, P < 0.05 vs. baseline for both). The estimated peak EIPSP-A and [Cl−]i induced by the two current magnitudes were significantly different from steady state values and from each other (P < 0.05). The increase of [Cl−]i over baseline (1 nA: by 9.8 ± 5.1 mm, 2 nA: by 23.7 ± 16.9 mm) was about twofold larger on doubling the current (P < 0.05).

Pharmacology of Cl− transport in HENC neurones

We first considered the possibility that an up-regulated NKCC1 (Palma et al. 2006) might cause an augmented inward transport in HENC neurones, as occurs perinatally (Dzhala et al. 2005). Application of bumetanide had no consistent effect on the amplitude of the pharmacologically isolated IPSPA (CDC-ACSF: 5.0 ± 3.2 mV; bumetanide: 6.4 ± 3.9 mV; n = 9, P > 0.05). The EIPSP-A was unaffected by bumetanide (CDC-ACSF: −57.2 ± 9.4 mV, bumetanide: −57.6 ± 8.5 mV; n = 6; P > 0.05; see Fig. 4D), and hence [Cl−]i was unaltered at 12.5 and 12.2 mm, respectively. Repeating Cl− injections during application of bumetanide (10 μm, n = 3; or 50 μm, n = 5) in CDC-ACSF revealed a consistent increase in the recovery τ from 19.4 ± 4.5 s to 24.0 ± 3.2 s (n = 8, P < 0.05; Fig. 10A–C). In some neurones we calculated the maximal [Cl−]i attained after injection, suggesting a [Cl−]i of 22.1 ± 11.9 mm in control and 19.9 ± 7.6 mm in bumetanide (n = 5, P > 0.05), and hence [Cl−]i increased by 7.4 and 6.8 mm, respectively. On return to CDC-ACSF, the τ recovered to control values (17.5 ± 2.4 s, n = 4; P < 0.05 vs. bumetanide, P > 0.05 vs. control). These data indicate that bumetanide has, on average, no effect on the EIPSP-A (Fig. 4D) despite a marked prolongation of recovery τ after Cl− loading (Fig. 10D).

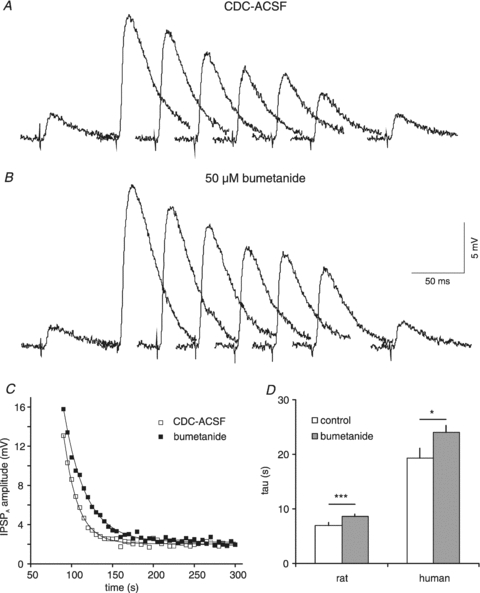

Application of furosemide (200 μm) markedly increased the amplitude of isolated IPSPA from 5.0 ± 2.4 mV to 9.0 ± 4.2 mV (n = 8, P < 0.001). Comparison of the EIPSP-A before and during the presence of furosemide revealed a marked shift from −61.1 ± 4.0 mV to −49.4 ± 5.4 mV (n = 6, P < 0.05, see Fig. 4B), corresponding to an increase in [Cl−]i from 10.5 ± 1.9 mm to 18.3 ± 4.5 mm (n = 6, P < 0.05). Furosemide also caused a marked increase in the τ of recovery from Cl− loading in HENC neurones. In three neurones, application of furosemide in ACSF increased the recovery τ from 20.4 ± 4.2 s to 50.0 ± 22.0 s. Application of furosemide in CDC-ACSF increased the τ from 15.5 ± 6.0 s to 44.1 ± 11.4 s (n = 8, P < 0.001; Fig. 11C, D). The maximal [Cl−]i reached after cessation of current injection was 18.7 ± 2.4 mm in CDC-ACSF and 26.9 ± 5.0 mm in the presence of furosemide (n = 6, P < 0.01). The actual increase of [Cl−]i by Cl− injection was unaltered (CDC-ACSF: 8.3 ± 1.8 mm; furosemide: 8.7 ± 5.4 mm; n = 6, P > 0.05). On return to CDC-ACSF, the τ recovered to the preceding control value (14.1 ± 6.4 s; n = 6, P < 0.001 vs. furosemide and P > 0.5 vs. CDC-ACSF). The EIPSP-A also essentially recovered to control values (−66.3 ± 6.4 mV; n = 4, P < 0.01 vs. furosemide, P > 0.05 vs. preceding control).

Figure 11. Effects of furosemide on the τ of IPSPA recovery in HENC neurones.

A and B, traces of IPSPA in a HENC neurone in CDC-ACSF (A) and in the presence of 200 μm furosemide (B). The time scale refers to both sets of traces. The traces before and at 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 260 s after the end of Cl− injection have been partly superimposed. C, plot of the average IPSPA amplitude from three consecutive injections in CDC-ACSF (open squares) and CDC-ACSF plus 200 μm furosemide (filled squares). The curves drawn represent the exponential fits to the data points with τ values of 9.7 s and 25.0 s, respectively. D, the mean τ in rat and HENC neurones in CDC-ACSF and in the presence of 200 μm furosemide in CDC-ACSF.

At this stage, the pharmacological evaluation had not revealed much about the underlying deficits of Cl− outward transport in most of the HENC neurones. To delineate the underlying deficits, changes in [K+]o were carried out. Reducing [K+]o from 5 to 2.5 mm had no significant effect on the kinetics of Cl− extrusion. In 2.5 mm K+, the τ of recovery was 17.5 ± 5.5 s compared with 16.8 ± 6.2 s under control conditions (5 mm K+ CDC-ACSF; n = 11, P > 0.05, Fig. 12D). The EIPSP-A increased from −60.8 ± 6.6 mV to −67.2 ± 8.1 mV in the presence of 2.5 mm K+ (n = 7, P < 0.05), exceeding the shift in Em (from −70.8 ± 3.9 mV to −73.2 ± 4.6 mV, P < 0.05).

Figure 12. Effects of Cs+ on IPSPA recovery τ in HENC neurones.

A, traces of IPSPA before and 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 90 s after Cl− injection (1 nA, 1 min) in a HENC neurone in CDC-ACSF. B, traces of the same neurone in CDC-ACSF with half of [K+]o replaced by Cs+ before and 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 90 s after the end of Cl− injection (1 nA, 1 min). Note the small spontaneous IPSPA (arrows). C, plot of the average IPSPA amplitude after cessation of Cl− injection in CDC-ASCF (open squares) and in the presence of Cs+ (filled squares) from the experiment shown in A and B. The curves represent exponential fits to the data (control: 10.3 s; Cs+: 15.4 s). D, plot of the mean τ values of IPSPA recovery in CDC-ACSF 5 mm K+, after reduction of [K+]o to 2.5 mm (left columns), and during application of 2.5 mm K+ plus 2.5 mm Cs+ in CDC-ACSF (right columns).

A deficit of K+-dependent routes of Cl− extrusion was further tested by equimolar replacement of 2.5 mm K+ with Cs+. The τ increased slightly from 15.0 ± 4.7 s (CDC-ACSF with 5 mm K+) to 17.5 ± 6.0 s (CDC-ACSF with 2.5 mm K+ and 2.5 mm Cs+; n = 9; P < 0.05; Fig. 12A and B). Comparison of the EIPSP-A revealed no effect of Cs+ (−61.9 ± 6.3 mV in CDC-ACSF and −60.3 ± 4.2 mV in the presence of 2.5 mm Cs+; n = 8, P > 0.05). These data suggest that the kinetics of Cl− extrusion from HENC neurones exhibits no detectable K+ and low Cs+ sensitivity (see Fig. 12D). Thus the large τ recovery in HENC neurones may relate to a deficit of K+-dependent pathways, i.e. KCC2.

The contribution of other routes of Cl− extrusion was investigated by iontophoresis of NO3−. Unfortunately, recording with KNO3-filled electrodes was difficult in HENC neurones. Impaled neurones were more fragile and in some, spontaneous synaptic activity at high frequency and large amplitude prevented determination of the τ of recovery in ACSF. Nevertheless, recovery from NO3− loading was observed in CDC-ACSF at a mean τ of 35.5 ± 17.3 s (n = 7). This is much larger than the τ of recovery from Cl− loading (P < 0.001, Fig. 13C). Recovery from NO3− injections in HENC neurones was also considerably slower than in rat cortical neurones (P < 0.01). This suggests that not only the fairly selective routes of Cl− extrusion (KCC2, NKCC1), but also the unselective, i.e. NO3−-carrying, pathways (AE and/or ClC2) may be impaired in HENC neurones.

Figure 13. IPSPA recovery following NO3− injections in HENC neurones.

A, traces of pharmacologically isolated IPSPA obtained before and at 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 and 260 s after cessation of NO3− injection. The amplitude may have been slightly affected by the initial AP (truncated). The time scale refers to the individual traces. Traces have been partly superimposed. B, plot of the IPSPA amplitude mean values from 6 injections in the neurone shown in panel A. The curve represents an exponential fit to the data points indicating a τ of decay of 34.2 s. C, comparison of IPSPA recovery τ values from Cl− or NO3− injections in rat and HENC neurones as indicated.

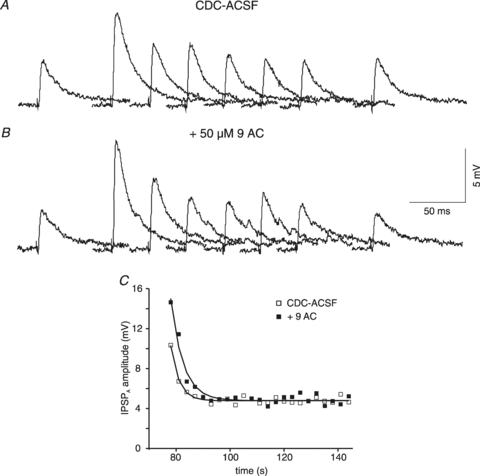

To test which of the two presumed unselective pathways, AE or ClC2, was reduced we applied 9AC. 9AC (50 μm) had no consistent effect on Em (see Fig. 4F) or the amplitude of the pharmacologically isolated IPSPA (control: 3.3 ± 3.2 mV, 9AC: 3.3 ± 2.7 mV; n = 7, P > 0.5). Accordingly, EIPSP-A and [Cl−]i were unaltered by 9AC (CDC-ACSF: −63.2 ± 6.7 mV, 9.6 ± 3.2 mm; 9AC: −62.3 ± 5.5 mV, 10.0 ± 3.0 mm; n = 8, P > 0.05 for both pairs). The recovery τ of the isolated IPSPA was marginally increased, from a mean 14.2 ± 6.2 s in CDC-ACSF to 16.2 ± 5.2 s in CDC-ACSF containing 9AC (n = 8, P < 0.05; Fig. 14A–C). Neither the maximal [Cl−]i at the end of Cl− injection (control: 14.8 ± 7.0 mm; 9AC: 16.3 ± 9.1 mm; n = 6, P > 0.5) nor the increase of [Cl−]i induced by injection of 1 nA for 1 min (control: by 5.2 ± 5.0 mm; 9AC: 6.2 ± 6.4 mm) was affected (P > 0.05). Compared to the considerable slowing of recovery by 9AC in rat neurones (from 6.6 to 8.4 s), the slight increase in τ suggests that 9AC-sensitive Cl− extrusion is relatively small in HENC neurones. This view is also supported by the similar increases of [Cl−]i in HENC neurones with and without 9AC, whereas in rat neurones the identical Cl− load caused a twofold larger increase of [Cl−]i in the presence of 9AC.

Figure 14. Effects of 9AC on HENC neurones.

A and B, traces of IPSPA from a HENC neurone in CDC-ACSF (A) and in the presence of 50 μm 9AC (B). The time scale refers to the individual traces. The traces before and at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 260 s after end of Cl− injection have been partly superimposed. C, plot of the average IPSPA amplitude from three consecutive Cl− injections in CDC-ACSF (open squares) and CDC-ACSF plus 50 μm 9AC (filled squares). The curves represent the exponential fits to the data points with τ values of 17.6 s and 18.7 s, respectively. D, plot of the mean values of recovery time constant in CDC-ACSF and after addition of 9AC in rat and HENC neurones.

Rates of Cl− efflux from HENC neurones

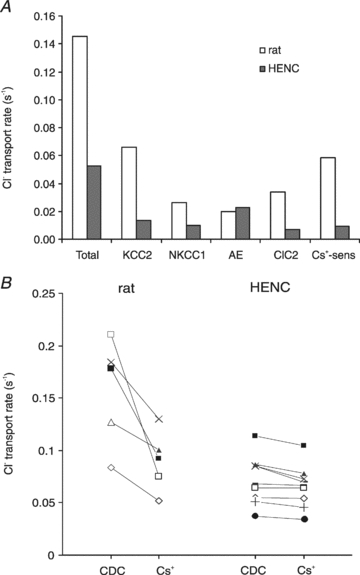

The time constants obtained under the various experimental conditions (Table 2) were converted into rates as described for rat neurones. The average τ obtained in CDC-ACSF yielded a total Cl− flux rate of 0.0526 s−1, 63.9% smaller than in rat neurones. From the bumetanide effects, a flux rate via NKCC1 of 0.0101 s−1, was obtained, i.e. 61.7% smaller than in rat neurones. The Cl− flux rate via ClC2 amounted to 0.0068 s−1, 79.9% smaller than in rat neurones (Fig. 15A). Assuming similar properties of ClC2 (i.e. only decreases in the number of transporters) the NO3− rate of ClC2 (0.0059 s−1) was calculated using the relative permeability determined in rat neurones (0.83). Thus the flux rate provided by the AE amounted to 0.0226 s−1, about 14% larger than in rat neurones. Finally, the calculated flux rate of KCC2 was 0.0132 s−1 or 0093 s−1 from the Cs+ experiments, i.e. 80.0% (calculated; or 84.1% from Cs+ experiments) smaller than in rat neurones. The relative contribution of the four pathways in HENC neurones can be ranked in descending order: AE: 43.0%, KCC2: 25.0%, NKCC1: 19.2%, and ClC2: 12.9%.

Table 2.

Time constants of recovery of TLE neurones under the different experimental condition

| Condition | τ (s) | Rate (s−1) | Isol. rates (s−1) | Calculation of rates for the different pathways | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACSF | 20.32 ± 11.38 (85) | 0.0492 | |||||

| CDC-ACSF | 19.02 ± 9.63 (62) | 0.0526 | 0.0526 | ||||

| CDC-ACSF | 19.36 ± 4.48 (8) | 0.0517 | |||||

| With bumet. | 24.05 ± 3.15 (8) | 0.0416 | 0.0101 | 0.0101 | −0.0101 | ||

| CDC-ACSF | 15.45 ± 6.02 (8) | 0.0647 | |||||

| With furos. | 44.10 ± 11.43 (8) | 0.0227 | 0.0420 | ||||

| CDC-ACSF | 14.80 ± 4.47 (8) | 0.0676 | |||||

| With 9AC | 16.45 ± 4.95 (8) | 0.0608 | 0.0068 | 0.0068 | −0.0056* | −0.0068 | |

| CDC-ACSF-5 mm K+ | 15.04 ± 4.69 (9) | 0.0665 | |||||

| CDC-ACSF-2.5 mm Cs+ | 17.48 ± 5.97 (9) | 0.0572 | 0.0093 | ||||

| CDC/nitrate | 35.48 ± 17.29 (7) | 0.0282 | 0.0282 | 0.0282 | −0.0226 | ||

| rate | 0.0101 | 0.0068 | 0.0226 | 0.0132 | |||

| pathway | NKCC1 | ClC2 | AE | KCC2 | |||

The time constants in control CDC-ACSF differ for some of the subgroups from the ensemble average. The rates were therefore calculated for each experimental group as difference in rate with and without the drugs. On the right hand the calculations of the rates of individual pathways are presented. To obtain the estimate for the AE, the NO3− rate of ClC2 has to be subtracted (see Table 1). To compensate for the lack of NO3− transport rate via ClC2, a calculated NO3− extrusion rate (indicated by the asterisk) was used (ClC2 rate for Cl− multiplied by 0.83, determined experimentally in rat neurones).

Figure 15. Average rates of chloride extrusion in rat and HENC neurones.

A, plot of the rates of Cl− extrusion obtained in rat and HENC neurones. The columns represent the rates of the total Cl− extrusion and the rates via the various pathways calculated according to eqns (1)–(5). The open and filled columns represent data from rat and HENC neurones, respectively. A graphical representation of the s.e.m. is not given since some values (KCC2 and AE) can only be calculated from the mean τ values. B, plot of the change in Cl− extrusion rate in individual rat and HENC neurones on application of 2.5 mm Cs+. Four HENC neurones with relatively high extrusion rates exhibited slight effects of Cs+ while five neurones with relatively lower rates in CDC-ACSF showed marginal effects.

The average values discussed above do not reflect possible changes in the transporters of individual neurones over time. Considering that the large scatter in time constants (Fig. 9A) may reflect snapshots of a progressive decline of Cl− homeostasis, it is tempting to sort these pictures into a sequential order. First, we tested our hypothesis that a decrease in KCC2 is the crucial initial step for altered Cl− homeostasis. In fact, changes in KCC2 mRNA and protein levels are preceded by functional reductions in KCC2 via tyrosine phosphorylation in hippocampal neurones (Wake et al. 2007). Therefore, we calculated the Cs+-sensitive rate as an index for KCC2 function of individual neurones. In rat neurones, an average Cs+-sensitive rate of 0.0584 s−1 was obtained. In HENC neurones, the rate was on average about 6-fold smaller (0.0093 s−1). If KCC2 declines first, neurones with a relatively small τ should have a sizeable Cs+-sensitive rate, and neurones with large τ values should have small rates. Segregating the neurones into two groups with τ values below or above 12 s revealed two distinct groups with mean τ values of 11.0 s and 18.3 s, respectively. The neurones with τ of 11 s exhibited a Cs+-sensitive rate of 0.0115 ± 0.0030 s−1 (n = 4), 17% of that in rat neurones. The other group with a mean τ of 18.3 s had an even smaller value (0.0023 ± 0.0023 s−1, n = 5, P < 0.05), i.e. the Cs+-sensitive rate was 3% of that in rat neurones. This indicates that the HENC neurones with the fastest Cl− recovery already had an 83% decrease in KCC2 function (or number of transporters) and neurones with large τ values even more (97%). Correspondingly, neurones with a relatively high Cl− extrusion rate exhibited slight rate changes on application of Cs+, whereas Cs+ had negligible effects in neurones with low rates (Fig. 15B). Segregating the effects of 9AC on τ in a similar fashion revealed that neurones with a small τ (<12 s, average 10.3 ± 0.9 s; n = 3) exhibited a 9AC-sensitive rate of 0.0105 s−1, which is about one-third of rat values, while the neurones with large τ values (>12 s, average 17.5 ± 3.3 s, n = 5) exhibited a smaller ClC2 rate (0.0065 s−1, i.e. about 20% of the rat 9AC-sensitive rate). In the series of bumetanide applications none of the neurones had τ values below 12 s, and we therefore arbitrarily used 15 s as a border. Three neurones exhibited τ values below 15 s (between 12.8 and 14.9 s, average 14.1 ± 1.1 s), and the recovery τ of the remaining neurones exceeded 20 s (range 21.6–24.5 s, average 22.5 ± 1.2 s, n = 5). The three neurones with intermediate τ values had a mean bumetanide-sensitive rate of 0.0287 ± 0.0011 s−1, which is similar to that of rat neurones (0.0263 s−1). The neurones with τ values exceeding 20 s had an average rate of 0.0049 ± 0.0050 s−1, i.e. about 5-fold smaller than the group of neurones with intermediate τ values. From these data we envisage an initial decline in KCC2 (an 80% decrease in KCC2 alone would increase the τ to about 12 s) and subsequent or concomitant decline in ClC2 by 80% would increase the time constant to near 16 s. The reverse order of decline is unlikely since HENC neurones with τ values near 10 s have a slightly smaller (68%) reduction in their ClC2-mediated rate, compared to KCC2, which is decreased by 82%. NKCC1 decreases last in this putative sequence of events since neurones with intermediate τ values (below 15 s) had normal NKCC1-mediated rates. A decrease in NKCC1 may cause the τ values between 20 and 30 s (see Fig. 9A). In fact, segregating the bumetanide data into two groups reveals that the group with τ values >20 s exhibited no significant change in τ on application of bumetanide (control: 22.5 ± 1.2 s, bumetanide: 24.1 ± 4.6 s; n = 5 P > 0.05). The group with intermediate τ values (14.1 ± 1.1 s) had a significantly smaller τ (P < 0.001) than the other group and exhibited a significant increase to 23.9 s ± 3.6 s (n = 3, P < 0.05). Interestingly, the values of these two groups in the presence of bumetanide were indistinguishable (P > 0.05). In this context it should be pointed out that only 16 neurones had τ values in the range of rat neurones (Fig. 9A), i.e. below 12 s, whereas 20 neurones exhibited τ values between 12 and 20 s, and in 24 neurones tau exceeded 20 s.

Discussion

Two main interrelated conclusions emerge from the data presented. Firstly, in about half of the HENC neurones, the EIPSP-A was much less negative (−55 mV) than in the other half (−69 mV). Secondly, Cl− extrusion in HENC neurones was much slower (average τ: 19 s) compared to rat cortical neurones (τ: 7 s) and exhibited a much larger variability between neurones.

Before discussing the cellular mechanisms underlying these two phenomena, we should briefly reiterate inherent problems in studying human tissue. The patients suffered years of epilepsy before operation, on average for about 20 years in the cases we investigated. Moreover, the patients had various medications that did not adequately control seizure activity. Human control tissues from tumour resections without seizure history were not available for the experiments in this study. The validity of comparison of data from human neurones with that from the rat may be debatable, although rodent neurones have provided indispensable data concerning the properties of channels and receptors in the healthy cortex as a reference for human tissues (Na+ currents: Cummins et al. 1994; H-currents: Wierschke et al. 2010; GABAA receptors: Gibbs et al. 1996; GABAB receptors: Teichgräber et al. 2009). As far as possible, human and rat tissue were treated in the same way in this study. Our data from rat neurones were by and large similar to those from various species (Connors et al. 1988; Thompson et al. 1988a; Deisz & Prince, 1989; Kaila et al. 1993; Luhmann & Prince, 1991). It could be argued that resected human tissue may suffer transient ischaemia and/or trauma during surgery, transport and slicing. Transient ischaemia may increase [Cl−]i as inferred from fluorometric measurements (Pond et al. 2006). Neuronal trauma is also capable of inducing a depolarizing shift of GABAA responses (van den Pol et al. 1996). However, both normal and depolarized EIPSP-A were observed in slices of a given human tissue. In addition, the HENC neurones appear to be fairly tough since Em and AP amplitudes were in the range typical of cortical neurones for astounding periods (often 24 h, Teichgräber et al. 2009). Therefore, we conclude that the depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated responses represent a crucial phenomenon of the human epileptogenic tissue. This view is supported by a previous report of depolarizing GABAA responses in slices of resected human subiculum correlating with interictal activity in vivo (Cohen et al. 2002).

Depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated responses in human epileptogenic cortex

Given the conclusion that the depolarizing EIPSP-A is related to the pathophysiology of epilepsy in vivo, a delineation of the underlying mechanisms may improve therapeutic strategies. The key question therefore concerns the mechanism governing an EIPSP-A near −55 mV, observed in about half of the HENC neurones. Two contending mechanisms, not mutually exclusive, have been proposed, namely, a decreased function (or number) of KCC2 transporters (Deisz et al. 1998) and an up-regulation of, presumed inwardly directed, NKCC1 transporters (Palma et al. 2006). The study by Palma et al. (2006) provided some mRNA data indicating a relative dominance of NKCC1 vs. KCC2 expression in human epileptogenic subiculum (see below).

Our data suggest that in HENC neurones several Cl− transport mechanisms are reduced. Such a change would be undetectable in patch-clamp recordings (Gibbs et al. 1996), since [Cl−]i is governed by the filling solution of the patch electrode rather than by the physiological transport across the membrane. Before discussing the pharmacology of Cl− homeostasis, we briefly consider the possible ionic mechanisms underlying the depolarizing IPSPA. Given a relative Cl−:HCO3− permeability of GABAA receptors of 1:0.2 (Kaila et al. 1993), the GHK equation allows calculation of [Ci-]i and ECl. The mean EIPSP-A of the ‘normal’ group of HENC neurones (−68.8 mV) yields a [Cl−]i of 6.9 mm corresponding to an ECl of −77.8 mV. Thus ECl is about 6 mV more negative than Em (−71.5 mV) and [Cl−]i about 2 mm lower than predicted by a passive distribution. The EIPSP-A of the second group (−55.2 mV), however, cannot be explained by a passive Cl− distribution, assuming an unaltered permeability ratio and Ebicarbonate. The calculation yields an ECl of −59.7 mV (at constant intracellular HCO3−), about 10 mV less negative than Em and a [Cl−]i of 13.7 mm about 5 mm higher than predicted by a passive distribution. Hence, either inward Cl− transport or an increased [HCO3−]i must underlie the more depolarizing EIPSP-A. Considering that inward transport by NKCC1 is slow (Achilles et al. 2007) and NKCC1 is reduced in HENC tissues (on average by 62%), inward Cl− transport via NKCC1 appears unlikely. To account for the EIPSP-A of −55 mV with passive Cl− distribution, either a [HCO3−]i of near 40 mm or an altered relative permeability of Cl−: HCO3− of 1:0.6 would be required, which is even less likely. Thus the presence of unaltered NKKC1-mediated rate in HENC neurones with intermediate τ values, when transport via KCC2 and ClC2 is greatly reduced (by 80%), may contribute to EIPSP-A values less negative than −64 mV. This value could be set by a passive Cl− distribution (Em of −71.5 mV) and the partial HCO3− permeability of GABAA receptors (Kaila et al. 1993).

The question then arises, which of the pathways can maintain ECl sufficiently negative to yield an EIPSP-A near Em despite HCO3− permeability? From a thermodynamic viewpoint NKCC1 is not capable of maintaining low [Cl−]i since the equilibrium of NKCC1-mediated transport is near −40 mV (Brumback & Staley, 2008). Regarding ClC2, the channels are activated by hyperpolarization (Clark et al. 1998), half-maximally at 15 mV more negative than ECl (Staley, 1994). However, this prerequisite for ClC2 contributing to a net Cl− efflux (Em much less negative than ECl) is hardly present in adult cortical neurones in steady state. Therefore, we favour KCC2 as the key pathway maintaining low [Cl−]i since the coupling of Cl− extrusion to the K+ gradient could push ECl to near −90 mV (Alvarez-Leefmans, 1990).

Kinetics and pharmacology of anion transport in neocortical neurones

First, we will discuss the data obtained during parallel experiments on rat cortical neurones. In essence, we corroborated and extended previous data from guinea pig cortex (Thompson et al. 1988a,b;). Despite different methods employed here (e.g. ether anaesthesia, submerged-type recording chamber, different cortex and cortical layers and 32°C) compared to the previous experiments (pentobarbitone anaesthesia, interface-type recording chamber), the τ values (7.9 s in ACSF) obtained are similar to those in neocortical neurones from guinea pig (τ 6.9 s at 36.5°C and 11 s at 32°C, Thompson et al. 1988a) and rat (Sprague–Dawley: τ 6.8 s at 35°C; Luhmann & Prince, 1991). Application of furosemide caused a marked slowing of recovery from Cl− loading, consistent with a large body of evidence indicating a reduced Cl− outward transport in the presence of furosemide in various neurones (Deisz & Lux, 1982; Misgeld et al. 1986; Thompson et al. 1988a; Jarolimek et al. 1999; DeFazio et al. 2000). We also observed a marked shift of the EIPSP-A from −62 mV to −54 mV, providing direct evidence that some furosemide-sensitive pathways maintain low [Cl−]i despite a constant load from the KCl in the recording electrode.

The significant slowing of recovery by bumetanide, similar to previous data (Thompson et al. 1988b), implies that a bumetanide-sensitive transporter, i.e. NKCC1, participates in Cl− extrusion. However, determination of the EIPSP-A with KCl-filled electrodes revealed no significant change by bumetanide. These two findings together suggest that bumetanide only affects the kinetics of Cl− extrusion at high levels of [Cl−]i such as those reached during iontophoresis, but not the net outward transport of Cl− at more moderate levels. In contrast to the view that bumetanide-sensitive transporters exclusively mediate inward transport of Cl−, we propose that NKCC1 contributes to outward Cl− transport.

K+ dependence of Cl− outward transport

Direct evidence for the presence of a K+-coupled transporter was obtained from the decreased recovery τ of the isolated IPSPA caused by reducing [K+]o (from 5 mm to 2.5 mm; see also Thompson et al. 1988a). Further evidence for a K+-sensitive outward transport was provided by the Cs+ experiments. Cs+, like NH4+, causes a reversible shift of the EIPSP towards resting Em (Aickin et al. 1982). Unlike NH4+, which is carried by KCC2 (Liu et al. 2003; Williams & Payne, 2004) thereby causing complicating intracellular pH changes (Williams & Payne, 2004; Titz et al. 2006), Cs+ decreases net outward transport by reducing the maximal velocity of KCC2-mediated transport (Williams & Payne, 2004). Our data demonstrating that 2.5 mm Cs+ (equimolar replacement of K+) increased the τ of recovery from 7.1 s to 12.2 s is in line with this notion and in turn indicates the presence of KCC2 in rat cortical neurones.

Contribution of AE and ClC2 to Cl− extrusion