Non-technical summary

In young healthy humans, the combination of exercise and hypoxia produces a compensatory vasodilatation to ensure the maintenance of oxygen to the active muscles. We have previously demonstrated that nitric oxide (NO) is a major factor responsible for the compensatory vasodilatation. In this paper we show that the compensatory vasodilator response to hypoxic exercise is attenuated in older adults due to less NO signalling. These findings provide important information on the impact of ageing and the role of NO in the regulation of skeletal muscle blood flow during conditions of reduced oxygen availability.

Abstract

Abstract

We tested the hypotheses that (1) the compensatory vasodilatation in skeletal muscle during hypoxic exercise is attenuated in ageing humans and (2) local inhibition of nitric oxide (NO) synthesis in the forearm of ageing humans will have less impact on the compensatory dilatation during rhythmic exercise with hypoxia, due to a smaller compensatory dilator response. Eleven healthy older subjects (61 ± 2 years) performed forearm exercise (10% and 20% of maximum) during saline infusion (control) and NO synthase inhibition (NG-monomethyl-l-arginine; l-NMMA) under normoxic and normocapnic hypoxic (80% arterial O2 saturation) conditions. Forearm vascular conductance (FVC; ml min−1 (100 mmHg)−1) was calculated from forearm blood flow (ml min−1) and blood pressure (mmHg). To further examine the effects of ageing on the compensatory vasodilator response to hypoxic exercise we compared the difference in ΔFVC (% change compared to respective normoxic exercise trial) between the older subjects (present study) and previously published data from an identical protocol in young subjects. During the control condition, the compensatory vasodilator response to hypoxia was similar between the old and young groups at 10% exercise (28 ± 6%vs. 40 ± 8%, P = 0.11) but attenuated at 20% exercise (14 ± 4%vs. 31 ± 6%, P < 0.05). l-NMMA during hypoxic exercise only blunted the compensatory vasodilator response in the young group (P < 0.05). Our data suggest that ageing reduces the compensatory vasodilator response to hypoxic exercise via blunted NO signalling.

Introduction

In young healthy humans submaximal exercise during hypoxia produces a compensatory vasodilatation relative to the same level of exercise under normoxic conditions (Rowell et al. 1986; Roach et al. 1999; Calbet et al. 2003; Wilkins et al. 2006, 2008; Casey et al. 2009, 2010). This compensatory vasodilatation during hypoxic exercise occurs to ensure an adequate oxygen delivery to the active muscles. We have previously demonstrated that nitric oxide (NO)-mediated mechanisms contribute to the compensatory vasodilatation at rest and during incremental hypoxic exercise (Casey et al. 2010). However, some evidence suggests that the forearm blood flow response to acute hypoxia at rest is inversely related to age (Kravec et al. 1972). Moreover, ageing has been reported to be associated with a lower exercise hyperaemia under normoxic conditions which may be due in part to reduced endothelial-derived NO and/or prostaglandins (Schrage et al. 2007; Crecelius et al. 2010). To our knowledge, no study has examined the effect of ageing on the vasodilator response during hypoxia exercise. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investigate the compensatory vasodilator response to hypoxic exercise in healthy ageing humans. We hypothesized that older subjects would demonstrate (1) an attenuated compensatory vasodilator response compared to young healthy subjects and (2) inhibition of NO would have less impact on the compensatory dilatation during hypoxic exercise in ageing humans, due to blunted NO signalling in the older subjects.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 11 older healthy subjects (6 female and 5 male; 55–70 years) volunteered to participate in the study. Subjects completed written informed consent and underwent a standard screening and were healthy, non-obese (BMI < 28 kg m−2), non-smokers and were not taking any vasoactive medications. Two subjects were taking bisphosphonates to prevent and/or treat osteoporosis, two subjects were taking aspirin (withheld for 1 week prior to study), and one subject was taking Synthroid to treat hypothyroidism (withheld 3 days prior to study). Subjects reported normal daily activities but no regular physical training. Seven subjects reported taking a daily vitamin. Studies were performed after an overnight fast and refraining from exercise and caffeine for at least 24 h. All female subjects were postmenopausal and were not taking any form of hormone replacement therapy. All study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board and were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Forearm exercise

Subjects performed rhythmic forearm exercise with a handgrip device by the non-dominant arm at 10 and 20% of each subject's maximal voluntary contraction (MVC, mean 34 ± 3 kg, range 21–55 kg), determined at the beginning of each experiment. The weight was lifted 4–5 cm over a pulley at a duty cycle of 1 s contraction and 2 s relaxation (20 contractions per minute) using a metronome to ensure correct timing. The average weight used for forearm exercise was 3.4 ± 0.3 and 6.9 ± 0.6 kg for 10 and 20% MVC, respectively.

Arterial and venous catheterization

A 20 gauge, 5 cm (Model RA-04020, Arrow International, Reading, PA, USA) catheter was placed in the brachial artery of the exercising arm under aseptic conditions after local anaesthesia (2% lidocaine) for administration of study drugs and to obtain arterial blood samples. The catheter was connected to a three-port connector in series, as previously described in detail (Dietz et al. 1994). One port was linked to a pressure transducer positioned at heart level (Model PX600F, Edwards Lifescience, Irvine, CA, USA) to allow measurement of arterial pressure and was continuously flushed (3 ml h−1) with heparinized saline with a stop-cock system to enable arterial blood sampling. The remaining two ports allowed arterial drug administration. Deep venous blood was sampled via an 18 gauge, 3 cm catheter inserted retrogradely in an antecubital vein (Joyner et al. 1992).

Heart rate and systemic blood pressure

Heart rate was recorded via continuous 3-lead ECG. A pressure transducer connected to the arterial catheter measured beat-to-beat blood pressure (Cardiocap/5, Datex-Ohmeda, Louisville, CO, USA)

Forearm blood flow

Brachial artery mean blood velocity and brachial artery diameter were determined with a 12 MHz linear-array Doppler probe (Model M12L, Vivid 7, General Electric, Milwaukee, WI, USA). Brachial artery blood velocity was measured throughout each condition with a probe insonation angle previously calibrated to 60 deg. Brachial artery diameter measurements were obtained at end diastole between contractions during steady-state conditions. Forearm blood flow (FBF) was calculated as the product of mean blood velocity (cm s−1) and brachial artery cross-sectional area (cm2) and expressed as millilitres per minute (ml min−1).

Systemic hypoxia

The hypoxic conditions involved a self-regulating partial rebreathe system that effectively clamps end-tidal CO2 at baseline levels despite large changes in minute ventilation during hypoxia (Banzett et al. 2000; Weisbrod et al. 2001; Wilkins et al. 2006, 2008). The level of inspired O2 was titrated to achieve an arterial O2 saturation (assessed via pulse oximetry) of ∼80%. The amount of O2 provided in the inspiratory gas was controlled by mixing N2 with medical air via an anaesthesia gas blender. Carbon dioxide concentrations were monitored (Cardiocap/5) and ventilation was assessed via a turbine (Model VMM-2a, Interface Associates, Laguna Nigel, CA, USA).

Pharmacological infusions

NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA; NOS inhibitor; Bachem, Switzerland) was infused at a loading dose of 5 mg min−1 for 5 min and then at a maintenance dose of 1 mg min−1 for the remainder of the study. Acetylcholine (ACh; a non-specific muscarinic agonist) was infused intra-arterially at 2.0, 4.0 and 8.0 μg (dl forearm volume)−1 min−1 for 2 min each to determine the endothelium-dependent vasodilator response before and after NOS inhibition with l-NMMA.

Blood gas and catecholamine analysis

Brachial artery and deep venous blood samples were analysed with a clinical blood gas analyser (Bayer 855 Automatic Blood Gas System, Boston, MA, USA) for partial pressures of O2 and CO2 ( and

and  ), pH and O2 saturation (

), pH and O2 saturation ( ). Arterial and venous O2 content was calculated using the measured

). Arterial and venous O2 content was calculated using the measured  and

and  values. Arterial and venous plasma catecholamine (adrenaline and noradrenaline) levels were determined by HPLC with electrochemical detection.

values. Arterial and venous plasma catecholamine (adrenaline and noradrenaline) levels were determined by HPLC with electrochemical detection.

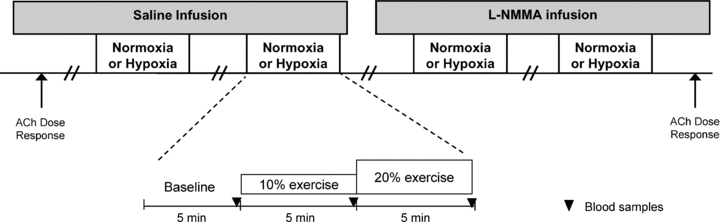

Experimental protocol

A schematic diagram of the general experimental design is illustrated in Fig. 1. Each subject completed a resting baseline condition followed by rhythmic forearm exercise at 10% which was immediately increased to 20% MVC during normoxia and normocapnic hypoxia. Exposure to normoxia or hypoxia was alternated and randomized. Resting baseline and forearm exercise (normoxia and hypoxia) were performed during a control (saline) infusion, followed by l-NMMA infusion. Due to the long half-life of l-NMMA, study drugs were always administered in the same order. A rest period of at least 20 min was allowed between conditions under each drug infusion. During each infusion and each condition (normoxia and hypoxia) arterial and venous blood was sampled at rest and at steady-state exercise for blood gas analysis and plasma catecholamine determination.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of experimental protocol.

Measurements were obtained at baseline and incremental exercise (10% and 20% of maximum) under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Both normoxic and hypoxic trials were performed during control (saline) and l-NMMA infusions. ACh, acetylcholine.

Data analysis and statistics

Data were collected at 200 Hz, stored on a computer and analysed off-line with signal processing software (WinDaq, DATAQ Instruments, Akron, OH, USA). Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was determined from the brachial artery pressure waveform and heart rate was determined from the electrocardiogram. Values for minute ventilation, end-tidal CO2 and O2 saturation (pulse oximetry) were determined by averaging minutes 4 and 5 at rest and during each exercise intensity. Forearm blood flow and arterial pressure were determined by averaging values from the 4th minute at rest and each exercise bout. Forearm vascular conductance (FVC) was calculated as (FBF/arterial pressure) × 100 and expressed as ml min−1 (100 mmHg)−1. The change (Δ) in FBF and FVC due to hypoxia at rest and due to hypoxic exercise (10 and 20%) was calculated by subtracting resting FBF and FVC during normoxia at each drug infusion (saline or l-NMMA) from FBF and FVC values obtained during hypoxia (at rest and during exercise) within each drug infusion. Blood gas and catecholamine values were determined from blood samples obtained during normoxia and hypoxia with each drug infusion. Arteriovenous oxygen difference during forearm exercise was calculated by the difference between arterial and venous O2 content. Venous–arterial noradrenaline difference (v–a noradrenaline difference) was calculated by the difference between venous and arterial noradrenaline concentrations.

All values are expressed as means ± SEM. To determine the effect of hypoxia with each pharmacological treatment, differences in absolute FBF and FVC at rest (normoxia and hypoxia) and differences in ΔFBF and ΔFVC at rest and during each exercise intensity (normoxia and hypoxia) were determined via repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). Haemodynamic, respiratory, blood gases and catecholamine variables were compared via repeated measures ANOVA to detect differences between responses during hypoxia at rest and during exercise across pharmacological infusions. Appropriate post hoc analysis determined where statistical differences occurred. Statistical difference was set a priori at P < 0.05.

To further examine the effects of ageing on the compensatory vasodilator response to hypoxic exercise we compared via ANOVA the difference in ΔFVC (% change compared to the respective normoxic exercise trial) between the older subjects (present study) and previously published data from an identical protocol in young subjects (6 males and 6 females; 26 ± 2 years) (Casey et al. 2010). These comparisons were made during the control saline trials as well as the l-NMMA trials to test our second hypothesis that inhibition of NO would have less impact on the compensatory dilatation during hypoxic exercise in ageing humans, due to blunted NO signalling in the older subjects.

Results

All 11 subjects completed the study. The subjects were 61 ± 2 years of age, 171 ± 3 cm in height and weighed 74 ± 4 kg (BMI: 25 ± 1 kg m−2). Their average total, LDL and HDL cholesterol and triglycerides were 191 ± 13, 117 ± 12, 55 ± 4 and 95 ± 9 mg dl−1, respectively.

Systemic haemodynamic and respiratory responses (Table 1)

Table 1.

Systemic haemodynamic and respiratory responses at rest and with incremental exercise during normoxia and hypoxia under control (saline) and NOS inhibition (l-NMMA)

| Normoxia | Hypoxia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | 10% | 20% | Rest | 10% | 20% | |

| Older adults (n = 11) | ||||||

| Control (saline) | ||||||

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 102 ± 4 | 106 ± 4 | 109 ± 4† | 103 ± 4 | 106 ± 5 | 107 ± 4 |

| Heart rate (beats min−1)* | 66 ± 3 | 70 ± 4 | 72 ± 4† | 78 ± 3 | 79 ± 3 | 81 ± 5 |

| Minute ventilation (l min−1; BTPS)* | 7.2 ± 0.6 | 7.1 ± 0.5 | 9.6 ± 1.1 | 11.7 ± 1.2 | 14.5 ± 1.4 | 16.9 ± 2.3† |

| End-tidal CO2 (mmHg) | 36 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 |

| l-NMMA | ||||||

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 105 ± 4 | 108 ± 4 | 111 ± 5† | 106 ± 4 | 109 ± 5 | 111 ± 4† |

| Heart rate (beats min−1)* | 66 ± 4 | 69 ± 4 | 73 ± 4† | 81 ± 4 | 82 ± 4 | 84 ± 4 |

| Minute ventilation (l min−1; BTPS)* | 8.3 ± 1.0 | 8.6 ± 0.8 | 11.0 ± 1.3 | 14.7 ± 1.5 | 18.1 ± 1.9†‡ | 21.1 ± 2.2†‡ |

| End-tidal CO2 (mmHg) | 37 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 |

| Young adults (n = 12) | ||||||

| Control (saline) | ||||||

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 89 ± 2 | 90 ± 2 | 93 ± 2 | 88 ± 2 | 90 ± 2 | 91 ± 3 |

| Heart rate (beats min−1)* | 62 ± 3 | 66 ± 3† | 68 ± 3 | 73 ± 4 | 77 ± 5† | 80 ± 5 |

| Minute ventilation (l min−1; BTPS)* | 6.3 ± 0.7 | 8.7 ± 0.7 | 9.1 ± 0.8 | 10.1 ± 1.7 | 13.7 ± 2.7† | 14.7 ± 2.1 |

| End-tidal CO2 (mmHg) | 37 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 |

| l-NMMA | ||||||

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | 91 ± 2 | 92 ± 2 | 95 ± 2 | 92 ± 2 | 92 ± 2 | 93 ± 2 |

| Heart rate (beats min−1)* | 62 ± 3 | 65 ± 3 | 68 ± 3† | 76 ± 5 | 81 ± 5† | 82 ± 5 |

| Minute ventilation (l min−1; BTPS)* | 8.3 ± 1.0 | 10.2 ± 1.3 | 11.9 ± 1.5† | 14.4 ± 3.1‡ | 16.5 ± 2.9 | 19.0 ± 3.0†‡ |

| End-tidal CO2 (mmHg) | 37 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 36 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 | 37 ± 1 |

Values are means ± SEM.

P < 0.05 vs. normoxia

P < 0.05 vs. rest

P < 0.05 vs. Control.

Data for young adults are from previously published work (Casey et al. 2010). BTPS, Body temperature and pressure, saturated.

The group data (mean ± SEM) for haemodynamic and respiratory responses due to combined forearm exercise and hypoxia with each drug infusion are presented in Table 1. As expected, heart rate and minute ventilation increased as a consequence of systemic hypoxia and incremental forearm exercise. Mean arterial pressure was elevated during normoxic and hypoxic exercise at 20% MVC but did not differ between drug conditions (saline vs.l-NMMA). By design, end-tidal CO2 was maintained throughout rest and incremental exercise under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions for both protocols.

Forearm exercise (Table 2)

Table 2.

Forearm haemodynamics at rest and with incremental exercise during normoxia and hypoxia under control (saline) and NOS inhibition (l-NMMA)

| Δ from normoxia rest | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | 10% | 20% | 10% | 20% | |

| Older adults (n = 11) | |||||

| Forearm blood flow (ml min−1) | |||||

| Control (saline) | |||||

| Normoxia | 66 ± 7 | 213 ± 23† | 338 ± 44† | 147 ± 18 | 272 ± 40 |

| Hypoxia | 79 ± 11 | 255 ± 30*† | 367 ± 49*† | 188 ± 26* | 300 ± 44 |

| l-NMMA | |||||

| Normoxia | 53 ± 7 | 191 ± 22† | 313 ± 35† | 136 ± 20 | 258 ± 33 |

| Hypoxia | 61 ± 10 | 217 ± 30†‡ | 340 ± 45†‡ | 164 ± 24*‡ | 288 ± 41 |

| Forearm vascular conductance (ml min−1 100 mmHg−1) | |||||

| Control (saline) | |||||

| Normoxia | 65 ± 7 | 200 ± 20† | 309 ± 38† | 135 ± 16 | 244 ± 34 |

| Hypoxia | 76 ± 9 | 240 ± 27*† | 340 ± 46*† | 175 ± 23* | 275 ± 40 |

| l-NMMA | |||||

| Normoxia | 53 ± 6 | 178 ± 20† | 286 ± 27† | 126 ± 19 | 233 ± 26 |

| Hypoxia | 56 ± 8 | 199 ± 24†‡ | 312 ± 39*†‡ | 146 ± 20‡ | 259 ± 36 |

| Young adults (n = 12) | |||||

| Forearm blood flow (ml min−1) | |||||

| Control (saline) | |||||

| Normoxia | 55 ± 5 | 205 ± 22† | 329 ± 35† | 150 ± 17 | 274 ± 29† |

| Hypoxia | 68 ± 8* | 245 ± 27*† | 388 ± 42*† | 190 ± 22* | 333 ± 37*† |

| l-NMMA | |||||

| Normoxia | 41 ± 4‡ | 174 ± 23† | 334 ± 44† | 131 ± 18 | 291 ± 38† |

| Hypoxia | 44 ± 5‡ | 202 ± 24†‡ | 341 ± 38†‡ | 161 ± 21*‡ | 300 ± 35†‡ |

| Forearm vascular conductance (ml min−1 100 mmHg−1) | |||||

| Control (saline) | |||||

| Normoxia | 62 ± 6 | 225 ± 22† | 354 ± 34† | 163 ± 17 | 292 ± 28† |

| Hypoxia | 76 ± 9* | 273 ± 28*† | 429 ± 39*† | 211 ± 23* | 367 ± 34*† |

| l-NMMA | |||||

| Normoxia | 44 ± 5‡ | 187 ± 23† | 349 ± 41† | 140 ± 17 | 302 ± 35† |

| Hypoxia | 49 ± 5‡ | 219 ± 24†‡ | 362 ± 37†‡ | 175 ± 20*‡ | 318 ± 32†‡ |

Values are means ± SEM.

P < 0.05 vs. normoxia

P < 0.05 vs. rest

P < 0.05 vs. Control.

Data for young adults are from previously published work (Casey et al. 2010).

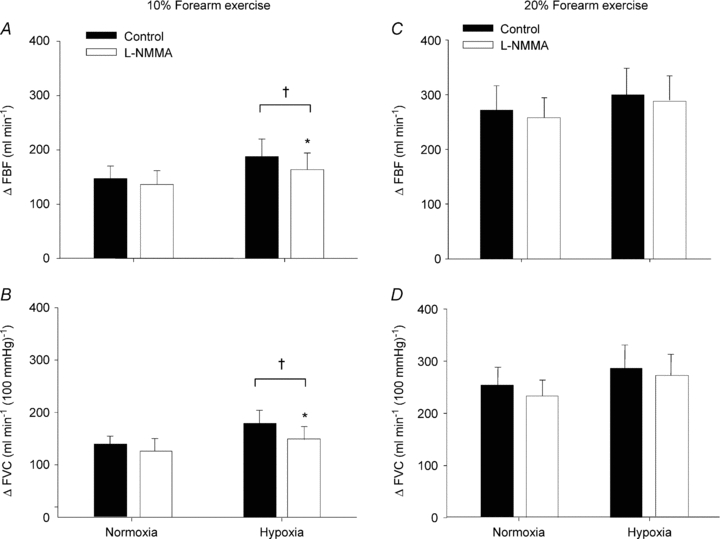

Presented in Table 2 are group data (mean ± SEM) forearm haemodynamics at rest and with increasing exercise intensity during control saline and l-NMMA infusion. Although not significant, resting FBF and FVC during systemic hypoxia tended to be higher than normoxia under the control (saline) conditions (P = 0.09 and 0.08, respectively). The absolute FBF and FVC to incremental hypoxic exercise were higher compared to normoxic exercise of the same intensity during the control saline infusion (main effect of hypoxia; P < 0.05; Table 2). However, the change (Δ) in FBF and FVC (relative to normoxic baseline values) to incremental hypoxic exercise was only greater than normoxic exercise during the 10% trials (P < 0.05; Fig. 2A and B), with no difference in ΔFBF and ΔFVC observed during the 20% trials (P = 0.22 and 0.12, respectively; Fig. 2C and D).

Figure 2. Change (Δ) in forearm blood flow (FBF) and forearm vascular conductance (FVC) due to hypoxic exercise during saline (control) and l-NMMA administration.

At 10% or 20% forearm exercise, NO synthase inhibition (l-NMMA) reduced forearm blood flow (A and C) and vascular conductance (B and D) compared to control (saline) during hypoxic exercise. †P < 0.05 vs. normoxia. *P < 0.05 vs. control (saline).

Intra-arterial administration of l-NMMA did not significantly decrease normoxic baseline (resting) blood flow below values observed during control saline infusion (P = 0.18). Additionally, l-NMMA infusion did not reduce absolute FBF or FVC (Table 2) or the ΔFBF or ΔFVC during normoxic exercise at 10 and 20% MVC compared to control saline (Fig. 2A–D). Although there was a trend for a reduced FBF and FVC during hypoxia at rest following l-NMMA administration it did not reach significance (P = 0.08 and 0.06, respectively; Table 2). Infusion of l-NMMA decreased absolute FBF and FVC (Table 2) with hypoxic exercise at 10% MVC (P < 0.05) and at 20% MVC (P < 0.05) compared to control saline infusions. However, the ΔFBF and ΔFVC with hypoxic exercise was only decreased during l-NMMA at 10% MVC compared to control saline infusions (Fig. 2A–D).

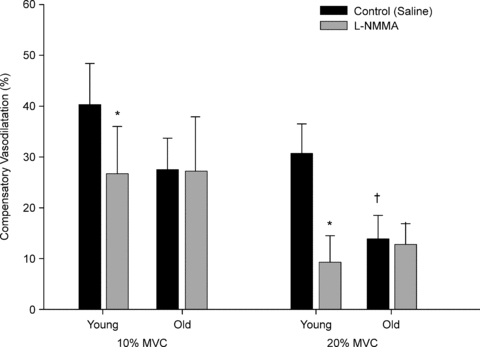

Compensatory vasodilatation in young versus older adults

To better understand the compensatory vasodilator responses to hypoxic exercise associated with ageing, we compared the present results to our previously published data in young adults (Casey et al. 2010). As seen in Fig. 3 the hypoxic compensatory vasodilatation (%) during control saline conditions tended to be lower in older adults at 10% MVC (P = 0.11) and was substantially lower at 20% MVC (P < 0.05). In young adults l-NMMA reduced the compensatory vasodilator response to hypoxic exercise at 10 and 20% MVC. However, l-NMMA had no effect on the compensatory vasodilatation in older adults (P = 0.96 and P = 0.87 for 10 and 20% MVC, respectively).

Figure 3. Impact of ageing on the compensatory vasodilator response (% change in ΔFVC compared to respective normoxic exercise condition) to hypoxic exercise.

Older adults tended to have an attenuated compensatory vasodilator response at 10% MVC (P = 0. 1) during control saline trials, whereas at 20% MVC the compensatory vasodilatation was substantially lower with ageing. l-NMMA significantly reduced the compensatory vasodilatation in young adults at both exercise intensities. However, there was no difference in the compensatory vasodilatation between control and l-NMMA trails in the older adults. Data for young adults is from previously published work (Casey et al. 2010). *P < 0.05 vs. control (saline); †P < 0.05 vs. young group.

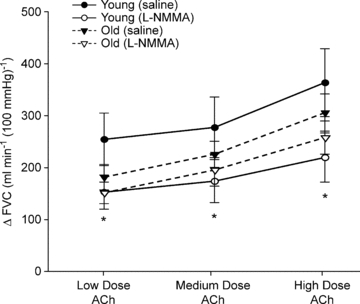

Vasodilator responses to exogenous acetylcholine

The change in FVC increased incrementally with each dose of ACh (2.0, 4.0 and 8.0 μg (dl forearm volume)−1 min−1) in the older adults (P < 0.05; Fig. 4). l-NMMA administration did not reduce the vasodilator response compared to the saline trials in the older adults (P = 0.27–0.38). When compared to our previously published data in young adults (Casey et al. 2010), the vasodilator responses to ACh under saline (control) conditions did not differ between age groups (P = 0.15). However, the vasodilator responses were substantially lower at all three doses of ACh in the presence of l-NMMA in the young adults (P < 0.01; Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Vasodilator response to exogenous acetylcholine (ACh) during saline and l-NMMA administration in young and older adults.

The change (Δ) in forearm vascular conductance (FVC) in response to increasing doses of ACh were not significantly different between young and older adults during the saline (P = 0. 5) or l-NMMA trials (P = 0.38). However, l-NMMA blunted the vasodilator responses (ΔFVC) to ACh at all three doses in the young adults. Data for young adults is from previously published work (Casey et al. 2010). *P < 0.01 vs. control (saline) for young adults.

Blood gases (Table 3)

Table 3.

Arterial and venous blood gas responses at rest and with incremental exercise during normoxia and hypoxia under control (saline) and NOS inhibition (l-NMMA)

| Normoxia | Hypoxia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | 10% | 20% | Rest | 10% | 20% | |

| Older adults (n = 11) | ||||||

| Control (saline) | ||||||

(%)* (%)*

|

97 ± 0 | 96 ± 0 | 96 ± 0 | 81 ± 1 | 80 ± 1 | 80 ± 1 |

(Torr)* (Torr)*

|

100 ± 2 | 97 ± 2 | 96 ± 2 | 46 ± 1 | 45 ± 1 | 46 ± 1 |

(Torr)* (Torr)*

|

37 ± 2 | 25 ± 1† | 27 ± 2 | 31 ± 1 | 22 ± 1† | 23 ± 1 |

| Arterial O2 content (ml l−1)* | 170 ± 5 | 176 ± 6 | 177 ± 6 | 143 ± 5 | 145 ± 4 | 149 ± 5 |

| Venous O2 content (ml l−1)* | 122 ± 10 | 76 ± 8† | 79 ± 10 | 104 ± 9 | 68 ± 7† | 64 ± 4 |

| a–v O2 (ml l−1)* | 48 ± 7 | 100 ± 5 | 99 ± 7 | 39 ± 5 | 77 ± 5 | 85 ± 3 |

| O2 consumption (ml min−1) | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 21.0 ± 2.3† | 33.4 ± 5.1† | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 19.2 ± 2.4† | 31.1 ± 4.1† |

| l-NMMA | ||||||

(%)* (%)*

|

96 ± 0 | 96 ± 0 | 97 ± 0 | 81 ± 1 | 80 ± 1 | 81 ± 1 |

(Torr)* (Torr)*

|

95 ± 2 | 95 ± 2 | 97 ± 1 | 47 ± 0 | 46 ± 1 | 46 ± 1 |

(Torr) (Torr) |

32 ± 2 | 22 ± 1† | 24 ± 1 | 26 ± 2*‡ | 19 ± 1‡ | 21 ± 1 |

| Arterial O2 content (ml l−1)* | 172 ± 6 | 171 ± 6 | 174 ± 6 | 146 ± 5 | 146 ± 5 | 150 ± 5 |

| Venous O2 content (ml l−1)* | 104 ± 11 | 66 ± 6† | 66 ± 4 | 87 ± 11‡ | 55 ± 7† | 57 ± 3 |

| a–v O2 (ml l−1) | 67 ± 9 | 105 ± 6† | 108 ± 5 | 60 ± 8‡ | 91 ± 6† | 94 ± 5 |

| O2 consumption (ml min−1) | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 19.9 ± 2.7† | 33.4 ± 3.7† | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 18.6 ± 2.6† | 31.0 ± 3.8† |

| Young adults (n = 12) | ||||||

| Control (saline) | ||||||

(%)* (%)*

|

97 ± 0 | 97 ± 0 | 97 ± 0 | 82 ± 0 | 82 ± 0 | 83 ± 0 |

(Torr)* (Torr)*

|

107 ± 3 | 107 ± 4 | 109 ± 3 | 48 ± 1 | 48 ± 1 | 49 ± 1 |

(Torr)* (Torr)*

|

38 ± 2 | 26 ± 1† | 27 ± 1 | 30 ± 1 | 22 ± 1† | 23 ± 1 |

| Arterial O2 content (ml l−1)* | 171 ± 5 | 173 ± 5 | 172 ± 5 | 144 ± 4 | 147 ± 4 | 149 ± 4 |

| Venous O2 content (ml l−1)* | 118 ± 8 | 68 ± 4† | 72 ± 4 | 95 ± 7 | 58 ± 4† | 59 ± 3 |

| a–v O2 (ml l−1)* | 53 ± 6 | 105 ± 4† | 100 ± 3 | 49 ± 6 | 88 ± 4† | 90 ± 3 |

| O2 consumption (ml min−1) | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 21.9 ± 2.9† | 33.6 ± 4.0† | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 21.6 ± 2.5† | 35.2 ± 4.3† |

| l-NMMA | ||||||

(%)* (%)*

|

97 ± 0 | 97 ± 0 | 97 ± 0 | 82 ± 0 | 81 ± 1 | 82 ± 1 |

(Torr)* (Torr)*

|

107 ± 3 | 106 ± 3 | 109 ± 3 | 47 ± 1 | 46 ± 2 | 49 ± 1 |

(Torr)* (Torr)*

|

34 ± 3 | 24 ± 1† | 28 ± 1† | 25 ± 1‡ | 20 ± 0†‡ | 23 ± 0† |

| Arterial O2 content (ml l−1)* | 173 ± 5 | 173 ± 5 | 176 ± 5 | 143 ± 4 | 141 ± 5 | 148 ± 4 |

| Venous O2 content (ml l−1)* | 105 ± 10 | 68 ± 7† | 80 ± 7† | 67 ± 5‡ | 51 ± 2† | 61 ± 3† |

| a–v O2 (ml l−1) | 68 ± 9 | 106 ± 7† | 95 ± 6 | 76 ± 4‡ | 91 ± 5*† | 87 ± 4 |

| O2 consumption (ml min−1) | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 18.1 ± 1.6† | 32.3 ± 3.5† | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 18.1 ± 2.7†‡ | 29.4 ± 4.0†‡ |

Values are means ± SEM.

P < 0.05 vs. normoxia

P < 0.05 vs. rest

P < 0.05 vs. control.

Data for young adults are from previously published work (Casey et al. 2010).

By design, systemic hypoxia reduced arterial oxygen saturation, arterial  and arterial oxygen content (P < 0.01 for all) at rest and with incremental forearm exercise during both drug trials (saline or l-NMMA). Acute hypoxia also decreased venous oxygen content during each drug infusion (P < 0.05). Under control (saline) conditions the lower arterial and venous oxygen content during hypoxic exercise led to a lower a–v oxygen difference compared to normoxic exercise (P < 0.05). However, the a–v oxygen difference during hypoxic exercise with l-NMMA did not differ to those observed during normoxic exercise. Forearm oxygen consumption increased similarly with normoxic and hypoxic exercise at 10 and 20% MVC during control saline infusion (Table 3). During l-NMMA administration, forearm oxygen consumption also increased with normoxic and hypoxic exercise. Forearm oxygen consumption was not different between drug conditions (control vs.l-NMMA) for either the normoxic or hypoxic trials.

and arterial oxygen content (P < 0.01 for all) at rest and with incremental forearm exercise during both drug trials (saline or l-NMMA). Acute hypoxia also decreased venous oxygen content during each drug infusion (P < 0.05). Under control (saline) conditions the lower arterial and venous oxygen content during hypoxic exercise led to a lower a–v oxygen difference compared to normoxic exercise (P < 0.05). However, the a–v oxygen difference during hypoxic exercise with l-NMMA did not differ to those observed during normoxic exercise. Forearm oxygen consumption increased similarly with normoxic and hypoxic exercise at 10 and 20% MVC during control saline infusion (Table 3). During l-NMMA administration, forearm oxygen consumption also increased with normoxic and hypoxic exercise. Forearm oxygen consumption was not different between drug conditions (control vs.l-NMMA) for either the normoxic or hypoxic trials.

Catecholamines (Table 4)

Table 4.

Adrenaline and noradrenaline at rest and incremental exercise during normoxia and hypoxia under control (saline) and NOS inhibition (l-NMMA)

| Normoxia | Hypoxia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rest | 10% | 20% | Rest | 10% | 20% | |

| Older adults (n = 11) | ||||||

| Control (saline) | ||||||

| Arterial noradrenaline (pg ml−1)* | 220 ± 25 | 247 ± 30 | 263 ± 25† | 253 ± 24 | 284 ± 19 | 314 ± 30† |

| Venous noradrenaline (pg ml−1)* | 359 ± 33 | 326 ± 36 | 328 ± 30 | 437 ± 49 | 385 ± 27 | 383 ± 33† |

| v–a noradrenaline difference (pg ml−1)* | 138 ± 17 | 79 ± 13† | 66 ± 9† | 184 ± 35 | 101 ± 12† | 79 ± 11† |

| Arterial adrenaline (pg ml−1)* | 63 ± 7 | 67 ± 9 | 70 ± 11 | 96 ± 9 | 118 ± 16 | 171 ± 49† |

| Venous adrenaline (pg ml−1) | 45 ± 11 | 51 ± 8 | 71 ± 12 | 60 ± 15 | 95 ± 16* | 149 ± 41*† |

| l-NMMA | ||||||

| Arterial noradrenaline (pg ml−1)* | 207 ± 19 | 223 ± 18 | 271 ± 19† | 251 ± 20 | 277 ± 21 | 318 ± 22† |

| Venous noradrenaline (pg ml−1)* | 331 ± 34 | 315 ± 30 | 352 ± 25 | 428 ± 38 | 406 ± 39 | 410 ± 28 |

| v–a noradrenaline difference (pg ml−1) | 124 ± 21 | 92 ± 13 | 81 ± 11† | 178 ± 24* | 129 ± 20*† | 92 ± 11† |

| Arterial adrenaline (pg ml−1)* | 74 ± 13 | 82 ± 14‡ | 88 ± 13‡ | 99 ± 11 | 127 ± 17 | 181 ± 51† |

| Venous adrenaline (pg ml−1) | 57 ± 13 | 70 ± 12‡ | 79 ± 14 | 71 ± 15 | 88 ± 13 | 152 ± 43*† |

| Young adults (n = 12) | ||||||

| Control (saline) | ||||||

| Arterial noradrenaline (pg ml−1)* | 108 ± 12 | 119 ± 13 | 136 ± 13† | 124 ± 11 | 132 ± 10 | 141 ± 12† |

| Venous noradrenaline (pg ml−1) | 161 ± 12 | 164 ± 15 | 182 ± 20 | 193 ± 9 | 176 ± 9 | 176 ± 11 |

| v–a noradrenaline difference (pg ml−1) | 45 ± 8 | 36 ± 10 | 36 ± 17 | 64 ± 10 | 40 ± 5 | 30 ± 6 |

| Arterial adrenaline (pg ml−1)* | 31 ± 4 | 35 ± 7 | 47 ± 7 | 50 ± 8 | 64 ± 8 | 79 ± 12 |

| Venous adrenaline (pg ml−1) | 15 ± 2 | 27 ± 4 | 33 ± 5 | 20 ± 5 | 47 ± 6*† | 66 ± 11*† |

| l-NMMA | ||||||

| Arterial noradrenaline (pg ml−1)* | 125 ± 13 | 128 ± 15 | 145 ± 17 | 118 ± 12 | 136 ± 15 | 150 ± 18† |

| Venous noradrenaline (pg ml−1) | 174 ± 16 | 158 ± 17 | 178 ± 18 | 182 ± 11 | 177 ± 12 | 190 ± 15 |

| v–a noradrenaline difference (pg ml−1) | 43 ± 10 | 24 ± 5† | 25 ± 4 | 54 ± 11 | 31 ± 6† | 28 ± 5 |

| Arterial adrenaline (pg ml−1)* | 31 ± 4 | 40 ± 6 | 47 ± 7 | 51 ± 9 | 76 ± 13 | 86 ± 12 |

| Venous adrenaline (pg ml−1) | 19 ± 2 | 37 ± 5† | 48 ± 7† | 23 ± 5 | 62 ± 9*† | 76 ± 10*† |

Values are means ± SEM.

P < 0.05 vs. normoxia

P < 0.05 vs. rest

main effect of drug, P < 0.05 vs. control.

Data for young adults is from previously published work (Casey et al. 2010).

Systemic hypoxia increased venous and arterial adrenaline during control saline and l-NMMA infusions (P < 0.05). Venous and arterial adrenaline increased with higher intensity exercise (20% MVC) under hypoxic conditions during control saline and l-NMMA infusions (P < 0.05). Additionally, systemic hypoxia increased venous and arterial noradrenaline both at rest and during incremental exercise.

Young vs. older adult comparisons

Tables 1–4 contain data from our previous study in young adults (Casey et al. 2010). The inclusion of the data from the young adults in the tables is to make comparisons between age groups across trials more straightforward. Aside from the primary aim of the study (age-related differences in hypoxic FBF and FVC; Fig. 3 and Table 2), we would like to point out that MAP was greater at rest and during exercise under all conditions in the older group (P < 0.01). This is consistent with several of our previous exercise studies (Proctor et al. 1998; Dinenno et al. 2005; Schrage et al. 2007).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine whether ageing alters the compensatory vasodilator response to hypoxic exercise. Our primary findings are (1) compensatory vasodilatation during moderate intensity (20% MVC) hypoxic exercise is attenuated in older adults and (2) this attenuated response is probably due to blunted NO signalling. These conclusions are supported by the fact that older adults did not demonstrate a significant difference in ΔFBF and ΔFVC during hypoxic exercise at 20% MVC compared to respective normoxic exercise conditions. Moreover, when compared to our previous study using an identical protocol in young adults (Casey et al. 2010), the compensatory vasodilator response (% change in ΔFVC compared to respective normoxic exercise trial) was substantially less with ageing (Fig. 3). Additionally, inhibition of NO failed to reduce the compensatory vasodilatation during hypoxic exercise in ageing humans, thus suggesting a blunted NO signalling in older adults.

Ageing is associated with a number of changes in arterial function and structure that are thought to compromise muscle blood flow or alter its regulation during dynamic exercise (Proctor & Parker, 2006). Along these lines, leg blood flow has been shown to be attenuated during normoxic exercise at submaximal and maximal workloads in older adults (Proctor et al. 1998, 2003; Beere et al. 1999; Poole et al. 2003; Lawrenson et al. 2004). However, this finding has not been consistent in the human forearm (Jasperse et al. 1994; Donato et al. 2006; Kirby et al. 2009). In the current study the older subjects demonstrated similar forearm blood flow and conductance responses to submaximal normoxic exercise as the younger comparison group used from our previously published study that utilized an identical protocol (Casey et al. 2010). Since NO has been reported not to be obligatory (Green et al. 2005; Martin et al. 2006; Casey & Joyner, 2009; Casey et al. 2010) or contribute minimally (Schrage et al. 2004) in forearm exercise-mediated hyperaemia under normoxic conditions in young adults we were not surprised by the similar responses between age groups.

Although the increase in blood flow to contracting forearm muscles during normoxic exercise appears to be preserved in older adults, we confirmed our primary hypothesis that there is a shift towards an impaired vasodilator response during exercise under conditions of systemic hypoxia. Additionally, the lack of change in compensatory vasodilatation following administration of l-NMMA suggests that the impaired vasodilator response with ageing is due to blunted NO signalling and is in agreement with our secondary hypothesis. The attenuated NO-mediated vasodilatation during hypoxic exercise could be due to several changes related to the production, activity and/or action of NO. First, there is some evidence that eNOS protein expression is lower in arteries of older compared with young rodents (Csiszar et al. 2002; Woodman et al. 2002), although this is not consistent across studies and appears to be dependent on the type of artery studied (van der Loo et al. 2000; Spier et al. 2004). However, recent evidence suggests that eNOS protein expression is not reduced in vascular endothelial cells of older men (Donato et al. 2009). Second, age-related increases in free radical scavenging can inactivate NO (via formation of peroxynitrite) (van der Loo et al. 2000) and possibly blunt NO-mediated vasodilatation during exercise. In this context, intra-arterial infusion of the anti-oxidant ascorbic acid has been shown to improve blood flow to the contracting forearm in older men and women during normoxic exercise (Kirby et al. 2009). Lastly, it is possible that the older subjects in the present study had altered vascular smooth muscle responsiveness to NO or other vasodilator signals. Unfortunately, we did not directly (i.e. infusion of sodium nitroprusside) test the responsiveness of the vascular smooth muscle in the present study. However, previous studies have demonstrated that sensitivity to NO is maintained in older adults (Taddei et al. 1996, 2000; Kirby et al. 2010). Taken together, if NO responsiveness was maintained in the present study, less NO production and/or a pronounced inactivation via free radicals potentially explain the blunted compensatory vasodilatation during hypoxic exercise in older adults.

Experimental considerations

The attenuated compensatory vasodilator response during hypoxic exercise in the older adults could be a result of a greater sympathetic vasoconstrictor restraint. Both ageing and hypoxia can have profound effects on the sympathetic nervous system. First, ageing is associated with increased basal sympathetic nerve activity and circulating noradrenaline levels (Sundlof & Wallin, 1978; Esler et al. 1995; Narkiewicz et al. 2005). Consistent with these previous reports, the older subjects in the current study demonstrated 2-fold higher venous noradrenaline levels at rest and during exercise than young adults from our previous study (Casey et al. 2010). Ageing is also associated with impaired modulation of postjunctional α-adrenergic vasoconstriction in contracting muscles (Dinenno et al. 2005). Taken together, the potential for an enhanced sympathetic restraint of muscle blood flow during hypoxic exercise in older adults exists. However, if a reduced functional sympatholysis occurred in the older adults there would probably have also been an attenuated blood flow during normoxic exercise compared to the young adults from our previous study (Casey et al. 2010).

Second, acute exposure to hypoxia increases sympathetic vasoconstrictor outflow to skeletal muscle vascular beds (Saito et al. 1988; Rowell et al. 1989) and can mask vasodilatation at rest (Weisbrod et al. 2001) and during forearm exercise (Wilkins et al. 2008). An exaggerated sympathetic response to hypoxic exercise in older adults could have blunted the vasodilator response during hypoxic exercise. However, changes in muscle sympathetic nerve activity in response to acute hypoxia does not appear to be enhanced in older men (Davy et al. 1997). Furthermore, the heart rate and blood pressure responses to hypoxic exercise were similar between the older (current study) and younger adults (Casey et al. 2010) of identical protocols. Therefore, it is unlikely that the blunted compensatory vasodilatation in older adults during hypoxic exercise was a result of an exaggerated sympathetic vasoconstrictor restraint.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, older subjects in the current study demonstrated a 15–30% lower vasodilator response to ACh (across doses) compared to the young adults; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.15). Similar, but significant age-related reductions (∼25–30%) in ACh-induced forearm vasodilatation have been reported by others (Taddei et al. 2001; Donato et al. 2008; Westby et al. 2011). The lack of significance in the current study, despite similar age-related reductions (%), may be related to differences in techniques used to measure the responses (Doppler vs. venous occlusion plethysmography) and/or the ACh doses administered. Of particular interest to the current study, l-NMMA failed to attenuate the vasodilator responses to ACh in the older group, whereas it substantially reduced the response in young adults. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating a lack of change in ACh-induced forearm vasodilatation following NOS inhibition (Taddei et al. 2000, 2001; Al-Shaer et al. 2006) and suggest a decreased NO bioavailability with ageing. Since the same loading and maintenance dose of l-NMMA was used in both groups, we do not feel the lack of change in the older group following l-NMMA administration is due to issues related to inadequate dosing.

Conclusions

This study when integrated with our previous findings in young adults (Casey et al. 2010) demonstrates that the compensatory vasodilator response to hypoxic exercise is attenuated in older adults. Furthermore, the present study suggests that the blunted vasodilator response is due to less NO signalling. We believe these findings provide important information on the impact of ageing and the role of NO in the regulation of skeletal muscle blood flow during conditions of reduced oxygen availability. From a clinical perspective, if this attenuated vasodilator response occurs in other vascular beds (i.e. coronary circulation) with ageing, older individuals may be at risk of reduced perfusion of the myocardium and consequently myocardial injury during exercise with hypoxia or ischaemia.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the study volunteers for their participation. We also thank Lakshmi (Madhuri) Somaraju, Christopher Johnson, Pam Engrav, Karen Krucker, Jean Knutson and Shelly Roberts for their technical assistance. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health research grants AR-55819 (to D.P.C.) and HL-46493 (to M.J.J.) and by CTSA RR-024150. The Caywood Professorship via the Mayo Foundation also supported this research.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- FBF

forearm blood flow

- FVC

forearm vascular conductance

- l-NMMA

NG-monomethyl-l-arginine

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MVC

maximal voluntary contraction

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

oxygen saturation

Author contributions

D.P.C.: conception and design of protocol, and revising the article critically for important intellectual content; T.B.C.: drafting the article; M.J.J.: conception and design of protocol, and revising the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to drafting the article, analysis and interpretation of data, and all approved the final version to be published. All experiments were performed at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

References

- Al-Shaer MH, Choueiri NE, Correia ML, Sinkey CA, Barenz TA, Haynes WG. Effects of aging and atherosclerosis on endothelial and vascular smooth muscle function in humans. Int J Cardiol. 2006;109:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banzett RB, Garcia RT, Moosavi SH. Simple contrivance “clamps” end-tidal PCO2 and PO2 despite rapid changes in ventilation. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1597–1600. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.5.1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beere PA, Russell SD, Morey MC, Kitzman DW, Higginbotham MB. Aerobic exercise training can reverse age-related peripheral circulatory changes in healthy older men. Circulation. 1999;100:1085–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calbet JA, Boushel R, Radegran G, Sondergaard H, Wagner PD, Saltin B. Determinants of maximal oxygen uptake in severe acute hypoxia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R291–R303. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00155.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey DP, Joyner MJ. NOS inhibition blunts and delays the compensatory dilation in hypoperfused contracting human muscles. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1685–1692. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00680.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey DP, Madery BD, Curry TB, Eisenach JH, Wilkins BW, Joyner MJ. Nitric oxide contributes to the augmented vasodilatation during hypoxic exercise. J Physiol. 2010;588:373–385. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.180489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey DP, Madery BD, Pike TL, Eisenach JH, Dietz NM, Joyner MJ, Wilkins BW. Adenosine receptor antagonist and augmented vasodilation during hypoxic exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1128–1137. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00609.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crecelius AR, Kirby BS, Voyles WF, Dinenno FA. Nitric oxide, but not vasodilating prostaglandins, contributes to the improvement of exercise hyperemia via ascorbic acid in healthy older adults. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1633–H1641. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00614.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Edwards JG, Kaminski P, Wolin MS, Koller A, Kaley G. Aging-induced phenotypic changes and oxidative stress impair coronary arteriolar function. Circ Res. 2002;90:1159–1166. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020401.61826.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davy KP, Jones PP, Seals DR. Influence of age on the sympathetic neural adjustments to alterations in systemic oxygen levels in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1997;273:R690–R695. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.2.R690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz NM, Rivera JM, Eggener SE, Fix RT, Warner DO, Joyner MJ. Nitric oxide contributes to the rise in forearm blood flow during mental stress in humans. J Physiol. 1994;480:361–368. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinenno FA, Masuki S, Joyner MJ. Impaired modulation of sympathetic α-adrenergic vasoconstriction in contracting forearm muscle of ageing men. J Physiol. 2005;567:311–321. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato AJ, Eskurza I, Jablonski KL, Gano LB, Pierce GL, Seals DR. Cytochrome P-450 2C9 signaling does not contribute to age-associated vascular endothelial dysfunction in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1359–1363. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90629.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato AJ, Gano LB, Eskurza I, Silver AE, Gates PE, Jablonski K, Seals DR. Vascular endothelial dysfunction with aging: endothelin-1 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H425–H432. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00689.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato AJ, Uberoi A, Wray DW, Nishiyama S, Lawrenson L, Richardson RS. Differential effects of aging on limb blood flow in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H272–H278. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00405.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esler MD, Turner AG, Kaye DM, Thompson JM, Kingwell BA, Morris M, et al. Aging effects on human sympathetic neuronal function. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1995;268:R278–R285. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.1.R278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DJ, Bilsborough W, Naylor LH, Reed C, Wright J, O’Driscoll G, Walsh JH. Comparison of forearm blood flow responses to incremental handgrip and cycle ergometer exercise: relative contribution of nitric oxide. J Physiol. 2005;562:617–628. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasperse JL, Seals DR, Callister R. Active forearm blood flow adjustments to handgrip exercise in young and older healthy men. J Physiol. 1994;474:353–360. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner MJ, Nauss LA, Warner MA, Warner DO. Sympathetic modulation of blood flow and O2 uptake in rhythmically contracting human forearm muscles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1992;263:H1078–H1083. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.4.H1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby BS, Crecelius AR, Voyles WF, Dinenno FA. Vasodilatory responsiveness to adenosine triphosphate in ageing humans. J Physiol. 2010;588:4017–4027. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.197814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby BS, Voyles WF, Simpson CB, Carlson RE, Schrage WG, Dinenno FA. Endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and exercise hyperaemia in ageing humans: impact of acute ascorbic acid administration. J Physiol. 2009;587:1989–2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kravec TF, Eggers GW, Jr, Kettel LJ. Influence of patient age on forearm and systemic vascular response to hypoxaemia. Clin Sci. 1972;42:555–565. doi: 10.1042/cs0420555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

Lawrenson L, Hoff J, Richardson RS. Aging attenuates vascular and metabolic plasticity but does not limit improvement in muscle.

. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1565–H1572. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01070.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;286:H1565–H1572. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01070.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Martin EA, Nicholson WT, Eisenach JH, Charkoudian N, Joyner MJ. Bimodal distribution of vasodilator responsiveness to adenosine due to difference in nitric oxide contribution: implications for exercise hyperemia. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:492–499. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00684.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K, Phillips BG, Kato M, Hering D, Bieniaszewski L, Somers VK. Gender-selective interaction between aging, blood pressure, and sympathetic nerve activity. Hypertension. 2005;45:522–525. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000160318.46725.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole JG, Lawrenson L, Kim J, Brown C, Richardson RS. Vascular and metabolic response to cycle exercise in sedentary humans: effect of age. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1251–H1259. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00790.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor DN, Koch DW, Newcomer SC, Le KU, Leuenberger UA. Impaired leg vasodilation during dynamic exercise in healthy older women. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1963–1970. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00472.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor DN, Parker BA. Vasodilation and vascular control in contracting muscle of the aging human. Microcirculation. 2006;13:315–327. doi: 10.1080/10739680600618967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor DN, Shen PH, Dietz NM, Eickhoff TJ, Lawler LA, Ebersold EJ, Loeffler DL, Joyner MJ. Reduced leg blood flow during dynamic exercise in older endurance-trained men. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:68–75. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach RC, Koskolou MD, Calbet JA, Saltin B. Arterial O2 content and tension in regulation of cardiac output and leg blood flow during exercise in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;276:H438–H445. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.2.H438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, Johnson DG, Chase PB, Comess KA, Seals DR. Hypoxemia raises muscle sympathetic activity but not norepinephrine in resting humans. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:1736–1743. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.4.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell LB, Saltin B, Kiens B, Christensen NJ. Is peak quadriceps blood flow in humans even higher during exercise with hypoxemia? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1986;251:H1038–H1044. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.5.H1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito M, Mano T, Iwase S, Koga K, Abe H, Yamazaki Y. Responses in muscle sympathetic activity to acute hypoxia in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1988;65:1548–1552. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.4.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrage WG, Eisenach JH, Joyner MJ. Ageing reduces nitric-oxide- and prostaglandin-mediated vasodilatation in exercising humans. J Physiol. 2007;579:227–236. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrage WG, Joyner MJ, Dinenno FA. Local inhibition of nitric oxide and prostaglandins independently reduces forearm exercise hyperaemia in humans. J Physiol. 2004;557:599–611. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spier SA, Delp MD, Meininger CJ, Donato AJ, Ramsey MW, Muller-Delp JM. Effects of ageing and exercise training on endothelium-dependent vasodilatation and structure of rat skeletal muscle arterioles. J Physiol. 2004;556:947–958. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.060301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundlof G, Wallin BG. Human muscle nerve sympathetic activity at rest. Relationship to blood pressure and age. J Physiol. 1978;274:621–637. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei S, Galetta F, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Salvetti G, Franzoni F, Giusti C, Salvetti A. Physical activity prevents age-related impairment in nitric oxide availability in elderly athletes. Circulation. 2000;101:2896–2901. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.25.2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei S, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Mattei P, Sudano I, Bernini G, Pinto S, Salvetti A. Menopause is associated with endothelial dysfunction in women. Hypertension. 1996;28:576–582. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.28.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei S, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Salvetti G, Bernini G, Magagna A, Salvetti A. Age-related reduction of NO availability and oxidative stress in humans. Hypertension. 2001;38:274–279. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.38.2.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Loo B, Labugger R, Skepper JN, Bachschmid M, Kilo J, Powell JM, et al. Enhanced peroxynitrite formation is associated with vascular aging. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1731–1744. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisbrod CJ, Minson CT, Joyner MJ, Halliwill JR. Effects of regional phentolamine on hypoxic vasodilatation in healthy humans. J Physiol. 2001;537:613–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westby CM, Weil BR, Greiner JJ, Stauffer BL, Desouza CA. Endothelin-1 vasoconstriction and the age-related decline in endothelium-dependent vasodilation in men. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011 doi: 10.1042/CS20100475. doi: 10.1042/CS20100475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins BW, Pike TL, Martin EA, Curry TB, Ceridon ML, Joyner MJ. Exercise intensity-dependent contribution of β-adrenergic receptor-mediated vasodilatation in hypoxic humans. J Physiol. 2008;586:1195–1205. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.144113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins BW, Schrage WG, Liu Z, Hancock KC, Joyner MJ. Systemic hypoxia and vasoconstrictor responsiveness in exercising human muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2006;101:1343–1350. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00487.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman CR, Price EM, Laughlin MH. Aging induces muscle-specific impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation in skeletal muscle feed arteries. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1685–1690. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00461.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]