Abstract

The flood of genome-wide data generated by high-throughput technologies currently provides biologists with an unprecedented opportunity: to manipulate, query and reconstruct functional molecular networks of cells. Here we outline three underlying principles and six strategies to infer network models from genomic data. Then, using cancer as an example, we describe experimental and computational approaches to infer “differential” networks that can identify genes and processes driving disease phenotypes. In conclusion, we discuss a network level understanding of cancer can be used to predict drug response and guide therapeutics.

Cells contain a vast array of molecular structures that come together to form complex, dynamic, and plastic networks. The recent development of high-throughput, massively-parallel technologies has provided biologists with an extensive, although still incomplete, list of these cellular parts. The emerging challenge over the next decade is to systematically assemble these components into functional molecular and cellular networks, and then to use these networks to answer fundamental questions about cellular processes and how diseases derail them.

For example, how do these cellular components come together to robustly maintain homeostasis, process exogenous and endogenous signals, and then coordinate responses? How do genetic aberrations disrupt the regulatory network and manifest in disease, such as cancer? In the Perspective, we reason that, even with a partial understanding of molecular networks, biologists are currently poised to understand how networks are deregulated in cancer cells and then predict how these networks might respond to drugs.

Quantitative biophysical network models encompassing a small number of components have made enormous contributions to our understanding of cellular networks. However, in this Perspective, we focus on deriving network models at a large systems scale from high-throughput data, using “data-driven network inference.” In this process, a set of modeling assumptions are defined, such as “genetic aberrations alter normal cellular regulation and drive tumor proliferation ” Then data is used to derive a specific model, such as specifying, for each tumor, which particular genes drive proliferation. In the end, a ‘good’ inference model of biological networks should be able to predict the behavior of the network under different conditions and perturbations, and ideally, even help us engineer a desired response. For example, where in the gene expression network of cancer cells should we perturb to reduce tumor proliferation or metastasis? Such a global understanding of networks can have transformative value, allowing biologists to dissect out the pathways that go awry in disease then identify optimal therapeutic strategies for controlling them.

To illustrate the potential impact of global models, we note that the effect of a cancer drug is often hard to predict because cross-talk and feedback are still poorly mapped in most signaling pathways. For example, the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is critical for cell growth, and its activity is aberrant in most cancers; hence, it was expected to be a good therapeutic target. Nevertheless, it shows poor results in clinical trials. This deviation from our expectations may be due to feedback and crosstalk between the Akt/mTOR and the extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) pathways(Carracedo et al., 2008). Inhibition of mTOR releases feedback inhibition of the receptor tyrosine kinases, which can activate both ERK and Akt (O’Reilly et al., 2006) and subsequently increase cell proliferation.

For targeted therapy to succeed, a global view of the interconnectivity of signaling proteins and their influences is critical. In this Perspective, we consider the current state and potential future of data-driven computational approaches to network inference, with an emphasis on applications to cancer. We will describe three principles underlying molecular networks and inferring these from data. These principles are matched to current experimental capabilities and will need revamping as technological leaps produce new types of data (e.g., more quantitative data and with real time dynamics). We then consider six promising experimental-computational strategies for constructing network-level models. While not exhaustive, these principles and strategies illustrate fruitful directions in network biology and will hopefully stimulate discussion and experimentation among computational and experimental biologists.

Principle 1: Molecular influences generate statistical relations in data

Network biology has been empowered by genomics technologies that enable the simultaneous measurement of thousands of molecular species. Such data offer a global unbiased view of the entire system, which in turn necessitates computation and statistics. The key underlying assumption frequently used for inferring networks from genomic data is that influences and interactions between biological entities generate statistical relations in the observed data. For example, if protein A activates protein B, then we expect to see high levels of protein B whenever levels or specific molecular states of its activator A are high. The reverse of this logic is that statistical correlation between proteins indicates a potential interaction between them. In a data driven manner, a computer can comprehensively test millions of such hypotheses in seconds and provide a statistical score for each candidate molecular interaction or influence. For example, one can test the statistical association between the copy number of regulator DNA copy number and gene expression of a target, for each locus and gene in the genome (see strategy 4).

Various statistical frameworks have been successfully applied to these network inference(Basso et al., 2005; Bonneau et al., 2007; Friedman et al., 2000); the commonality between the frameworks is that they model a target’s behavior as a function of its regulators and search for the most predictive regulator set. For example, Bayesian networks were used to reconstruct detailed signaling pathway structures in human T-cells using only the concentration of phospho-proteins simultaneously measured in individual cells (Sachs et al., 2005). Based solely on this data, this network analysis discovered the majority of known influences between the measured signaling components without prior knowledge of any pathways. Moreover, the analysis uncovered a new point of cross-talk, which was confirmed experimentally.

The same computational approach and mathematical formulae correctly reconstructed yeast metabolic networks from gene expression data(Pe’er et al., 2001). Together, these studies demonstrate the universal nature of statistical dependencies; the same formalism can be used to reconstruct yeast metabolic networks from gene expression data and mammalian signaling networks from phospho-protein abundances

Mathematical models of molecular networks have been derived from basic biochemical principles for decades, combining chemical reaction equations into a quantitative model. For example, Michaelis Menten equations are frequently used to model transcription factor binding to DNA. Nevertheless, most contemporary datasets lack the quantization and statistical power to resolve such models, even for small networks. Data driven approaches typically necessitate hundreds of samples to gain the statistical power to resolve even a partial qualitative map of molecular interactions. Data requirements are highly dependent on the number of components modeled, the mathematical complexity of the equations representing the molecular interactions, and the effect size of the influences themselves. Thus, at the heart of data-driven modeling is finding the sweet spot in the trade-off between more realistic (e.g., chemical reaction equations) and simpler models that can be inferred more robustly from data (e.g., linear regression).

One option is to build qualitative, rather than quantitative models. These models can identify qualitative features such as “Mek (mitogen-activated protein kinase) activates Erk” or that “Met4 and Met28 are required together to induce sulfur metabolism.” If quantitative modeling is important for the problem at hand, linear regression models provide a robust alternative to non-linear models (e.g., target gene expression is a linear combination of its transcription factors). Although non-linear relations frequently occur in biology, linear regression models are more robust and thus, they often give better results, even when the underlying model is non-linear. A detailed molecular model that is exhaustive in its molecular species and in the modeling of their interactions remains beyond our reach for the near future.

A powerful strategy in systems biology is to abstract and simplify models. In the “module-network” approach(Segal et al., 2003), genes are grouped into modules that are assumed to share a regulatory program. The rationale for this grouping is based on numerous examples in which the same regulatory circuits coordinate activation or repression of groups of genes that are involved in the same process (e.g. the entire ribosome complex is regulated by common transcription factors). By pooling many similar genes together, the module-network framework significantly increases the statistical power to identify regulatory influences(Litvin et al., 2009).

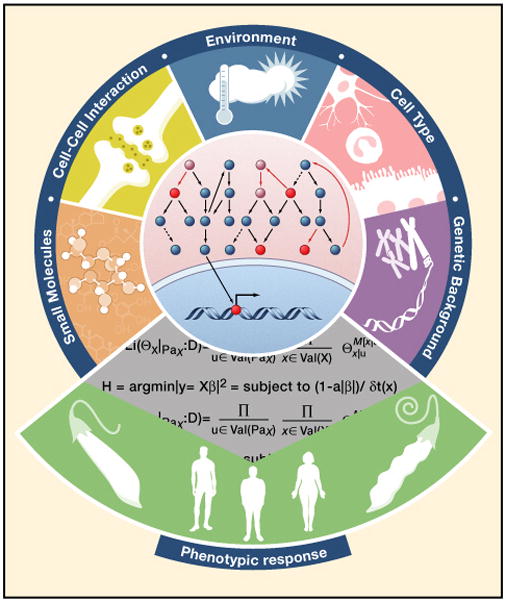

Principle 2: Networks are not fixed: the role of context and dynamics

Molecular networks are not static; rather, they exhibit dynamic adaptations in response to both internal states and external signals. Influences that determine network context can be divided into four categories. (1) Genetic background strongly determines network behavior and gives rise to significant differences across individuals (and even cells in the special case of cancer). (2) Cell lineages have dramatically different network structures because of epigenetic changes and differential expression of genes. (3) Tissue milieu can reprogram networks and their behaviors, as stromal cells do for tumors. (4) Exogenous signals, such as nutrients and other chemicals affect networks (Figure 1). Ultimately, health or disease emerges from an individual’s integration of internal and external cues.

Figure 1.

In cancer, context can have profound impact on how patients respond to therapies. For example, in recent clinical trials of a new generation of rationally targeted therapies (e.g., Gleevec, Herceptin and BRAF inhibitors for chronic myelogenous leukemia, breast cancer and melanoma, respectively), even patients that share that share the targeted mutation and tumor type displayed substantially variable responses to the drugs (Sharma et al., 2010a). In addition, in another recent trial (i.e., phase II) a therapy was extremely effective at reversing tumors in metastatic melanoma patients carrying the oncogenic BRAF mutation (Flaherty et al., 2010), in which this drug effectively shuts down the ERK pathway critical for this cancer. Strikingly, however, the same drug leads to the activation of the ERK pathway in cells with wild-type BRAF (Poulikakos et al., 2010), potentially promoting tumors in these cells.

To gauge such network activity, response, and potential, experiments must deliberately perturb the cell. For example, blood cells from acute myeloid patients could not be differentiated from healthy cells when only the basal levels of phosphorylation of key signaling molecules were measured. Only when the samples were interrogated with growth factors and cytokines did the resulting signaling profiles correlate with tumor genetics, drug response, and disease outcome (Irish et al., 2004). The importance of interrogation with stimuli comes into play because many important signaling responses, such as ERK2 activation in response to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), depend only on fold change, rather than basal protein levels that exhibit a high degree of variance (Cohen-Saidon et al., 2009).

Cellular responses often involve multiple feedback loops and additional complexities (see Regev review in current issue). For example, the transcriptional response to EGF stimulation induces feedback attenuation factors, such as dual-specific phosphatases (DUSPs), which shut down the same pathways that activate EGF target genes (Amit et al., 2007). Therefore, to understand tumor network function, drug response and the emergence of drug resistance, tumors must be systematically interrogated with different stimuli and drugs, followed by time series measurements. These measurements can then be used to derive a model describing the quantitative temporal sequence of events from the initial detection of an input to the tumor’s response. The goal would be to generate a model that has a reasonable chance of being able to predict responses to new, previously unmeasured inputs, such as new drugs or combinations of drugs.

Principle 3: Extracting ‘differential’ networks’

Given the importance of context, a central challenge for the field will be to collect data across multiple environments, cell types, and genetic backgrounds using genome-wide profiling to infer network connectivity and function in each context. Rather than explicitly modeling all the moving parts of a network, we propose that it is feasible to derive models that focus on key components by capturing the essential differences in network wiring, function and response between contexts (Figure 1).

A “differential-network” model is designed to elucidate the following: How do a small number of changes to the network (e.g., genetic, epigenetic) alter the function of the network? At the center of such a model are the altered nodes (i.e., genes or proteins) and data driven computation can be used to: (1) identify additional components that interact with these altered nodes; (2) qualify and quantify how these interactions are perturbed; (3) and model how these network perturbations continue to propagate though additional components to generate the phenotype of interest, such as proliferation, invasion, or drug response. For example, Carro et al., (2010) identify C/EBPβ and STAT3 as “master” transcription factors for which their over-expression synergistically activates expression of mesenchymal genes and subsequent tumor aggressiveness in malignant glioma (see strategy 3).

The network model can be significantly simplified because only the components that play a role in the modeled response need identification and inclusion. Importantly, the differential network strategy does not apply only to disease. It can be used in any context to address questions such as, what is the difference between two cell types or how does nutrient status affect cellular behavior?

Here we present six strategies that combine experimental and computational approaches to generate network inference models in the context of cancer. Strategies 1 and 2 focus on identifying key components; strategies 3 and 4 focus on deriving key network components concurrently with their regulatory influences; and strategies 5 and 6 advance towards increasingly detailed quantitative models of network influences.

Strategy 1: Discovery of inherited alleles and somatic mutations

Chromosomal aberrations and somatic sequence mutations are a hallmark of tumor cells. Multiple genetic aberrations collectively influence the expression of thousands of genes, altering the pathways and processes underlying malignant behaviors. The emergence of high-resolution copy number assays and massively parallel sequencing technologies opens the possibility of tracing phenotypic differences back to their genetic source. Large-scale initiatives are currently sequencing thousands of tumor genomes to comprehensively catalog the prevalent sequence mutations and chromosomal aberrations underlying each cancer type. Indeed, entire cancer genomes have already been sequenced in dozens of tumors, revealing a surprising degree of mutations and chromosomal aberrations in each individual cancer (Stephens et al., 2009). On the other, exon capture techniques, called exome sequencing (Ng et al., 2010), concentrate on the 1% of coding sequence in the human genome. This technique enables a more economical cataloging of coding mutations in cohorts of hundreds of tumors per cancer type. Finally, transcriptome (or RNA) sequencing identifies expressed coding and non-coding RNA mutations. Transcriptome sequencing also reveals fusion genes created by intronic translocations, which are therefore undetected by exon sequencing techniques (Maher et al., 2009).

These large-scale sequencing projects have uncovered a staggering diversity of genetic aberrations across tumors. Although each individual tumor typically harbors a large number of aberrations, only a few play a role in pathogenesis. Therefore, distinguishing between genetic changes that promote cancer progression mutations (i.e., driver mutations) and neutral mutations (i.e, passenger) is like finding needles in haystacks.

Recurrence was a rule of thumb for copy number aberrations (Weir et al., 2007). Thus, it was unforeseen that only a handful of genes would recurrently be targeted by sequence mutations in each cancer type. The current presumption is that the majority of the driver mutations are unique to each tumor. A key unresolved computational challenge is, therefore, to identify the driver mutations associated with each cancer genome. Indeed, the identification of these drivers is required before a “differential-network” approach can model how the pathogenic behavior emerges. Computational methods addressing this task are still under development (Akavia et al., 2010; Beroukhim et al., 2010; Carter et al., 2009).

Although recurrence may not occur at the gene level, significant recurrence does occurs at the level of pathways. For example, in glioblastoma, the majority of tumors have mutations in each of three signaling pathways: P53, RB1 (Retinoblastoma protein 1), and RAS (RAt Sarcoma)/P13K (Network, 2008). Since these findings define pathways, rather than genes, as unifying explanations for tumor progression, it is clear that finding drivers will rely on knowledge of molecular networks.

Unfortunately, there is currently insufficient information on pathways in existing databases. First, the majority of signaling proteins are not associated with any known pathway. Second, existing databases include only a small part of what is known and do not take context (e.g. cell type) into account. More sophisticated experimental and computational methods will be needed to define and catalog the components involved in each pathway. A promising direction is the use of systematic experimental and computational approaches to build interaction maps (Amit et al., 2009; Bandyopadhyay et al., 2010), which can subsequently be used to identify key aberrant genes. For example, an algorithm known as IDEA (interactome dysregulation enrichment analysis) (Mani et al., 2008) uses a specially derived context-specific molecular network to identify key aberrant genes in lymphoma.

Strategy 2: Discovering key network components using RNAi

Although naturally occurring genetic alterations help nominate causal genes in cancer and other diseases, deliberate perturbation greatly facilitates causal gene identification. Taking advantage of sequenced genomes, mammalian interference (RNAi) libraries have emerged as a central tool for systematic perturbation of any gene. Indeed, RNAi-based screens have proven to be a major tool in cancer research in which cell lines are readily available and cell proliferation and survival provide surrogates of tumorigenesis.

In one strategy, unbiased genome-wide RNAi screens in vitro and in vivo are used to identify candidate causative oncogenes and tumor suppressors that impact cell proliferation or survival. Typically, candidate genes that are found to have an aberrant sequence mutation, copy number alteration, or expression change in tumors are usually selected for deeper mechanistic characterization (Boehm et al., 2007; Ngo et al., 2010). However, one must always keep in mind that candidate genes that are not aberrant may be equally important to study and target therapeutically.

In a second strategy, candidate genes are first selected from cancer genomic datasets and then validated with small-scale RNAi screens. For example, this strategy was recently used to identify critical genes within tumor chromosomal deletions (Ebert et al., 2008) and for finding the small subset of genes that impact metastasis among hundreds selectively expressed in metastatic tumor (Bos et al., 2009).

Finally, unbiased screens can also shed light on the susceptibility or resistance of specific tumors to treatment (Holzel et al., 2010) and to find ways to enhance the effects of current therapies, such as taxanes (Whitehurst et al., 2007). Indeed, these types of findings can rapidly influence clinical research and practice. In all cases, RNAi serves as a ‘functional filter’ to pinpoint or annotate genes that affect proliferation, death, metastasis, or any cellular processes.

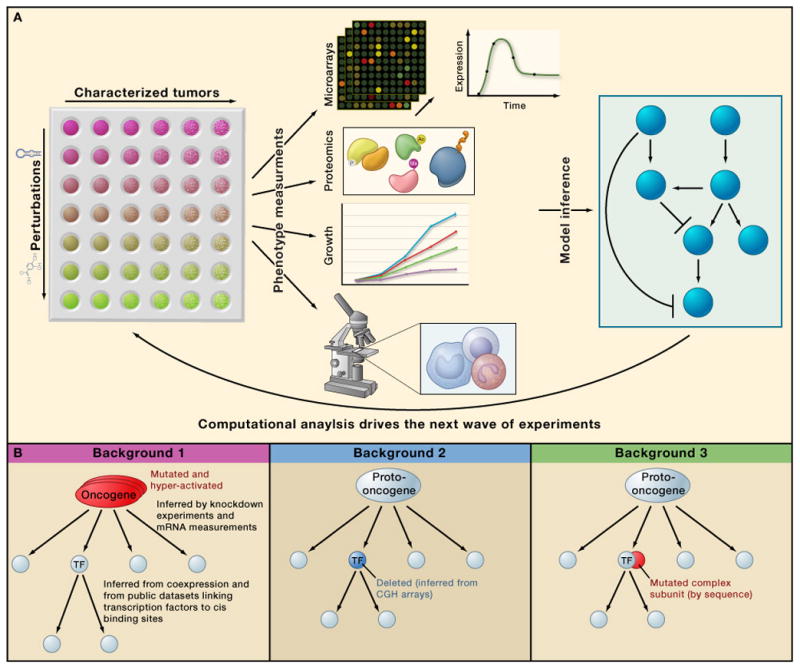

Combining computationally-guided experiment design with RNAi screens has enormous untapped potential. Although genome-wide datasets are the most comprehensive, they are also expensive to perform at the large scale required to cover all contexts. A more economical approach is to refine our understanding with iterative cycles of experimentation and computation. Computational hypotheses derived from one dataset are used to design the experiments for collecting the next dataset (figure 2). For example, protein interaction maps and microarray expression data were used to nominate high likelihood genes for characterization in a RNAi screen that dissects interactions between influenza and its host (Shapira et al., 2009). This approach deepened our understanding of how the virus manipulates or is controlled by key host defenses through direct and indirect interactions with 4 major host pathways.

Figure 2.

In the cancer setting, a good network model combined with computational inferences can suggest which gene combinations, genetic background, and cell assay (e.g., proliferation, invasion, metabolism) should be matched in searching for new components. For example, multiple mutations must occur together to produce a tumor (Land et al., 1983), necessitating a combinatorial RNAi approach. However, a large-scale combinatorial RNAi screen is not feasible, but, computational selection of likely combinations renders the experiments feasible. Second, although most screens are performed in a single genetic background, in reality, the functional impact of perturbation is highly dependent on genetic background: disrupting the expression of gene can cause death in one cell line and have no effect in another cell line (Luo et al., 2008). Thus, it would be useful to select cell lines with informative genetic backgrounds. Finally, a good model can link genes with specific biological processes (Akavia et al., 2010) and help us efficiently extend RNAi studies to problems of invasion, metabolism, cell-cell interactions, and other cancer hallmarks that are poorly understood (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2000).

Strategy 3: Statistical identification of dysregulated genes and their regulators

After discovering key network components, the next step is to decipher the wiring of the network. The majority of the computational work in this area has been through the analysis of tumor gene expression profiles that have accumulated on the order of tens of thousands microarrays over the past decade. Unlike the top down strategies described above, here the approach is bottom up: first identify the differentially expressed genes relevant to a tumor phenotype of interest and then use these genes to pinpoint the master regulator that brings about their dysregulation.

Data driven approaches (Principle 1) have been particularly powerful at locating the dysregulated genes and regulatory relations within tumor-related pathways. Analysis of glioblastoma gene expression profiles using the ARACNE (Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks) (Basso et al., 2005) algorithm revealed two master regulators of mesenchymal transformation in malignant glioma (Carro et al., 2010): the gene module that corresponds to the mesenchymal transformation and the transcription factors most likely regulating this module (based on mutual information between regulator and targets). Both transcription factors were then confirmed experimentally.

By extending this statistical reasoning to higher dimensions, the MINDY (Modulator Inference by Network DYnamics) algorithm (Wang et al., 2009) could cleverly identify post-translational activators and inhibitors of master regulators. Based on the assumption that high (or low) expression of such activators (or inhibitors) would lead to increased (or reduced) co-regulation of MYC with its known targets. MINDY uncovered new post-translational modifiers of MYC in human B lymphocytes, and 4 of them were validated using RNAi. Demonstrating the generality of the statistical approach, the identified modifiers were found to act by diverse mechanisms, including protein turnover, transcription complex formation, and selective enzyme recruitment.

As we wait for the development of experimental technologies that detect most post-translational changes in high-throughput, thousands of existing mRNA expression datasets can benefit from this powerful statistical approach to predict key modulators of regulatory activity, by any biochemical mechanism. We have thus, only begun to tap into the potential of these approaches to uncover the regulatory mechanisms that lead to tumors and other pathogenic phenotypes. Moreover, once profiles of cancer proteomes and their post-translational modifications become more readily available, these methods will be dramatically empowered.

Strategy 4: Integrating genotype and gene expression into causal models

Current analysis has only scratched the surface of existing datasets, and there is critical need for powerful computational approaches to expose the wealth of hidden information. A promising approach is “data integration” that builds a model from diverse data types (e.g., gene sequence, gene expression profiles, and protein-protein interactions), which each shed a different light on the underlying biology. The resulting combination is more than the sum of the parts (See Ideker review in current issue). A natural integration that captures the essence of ‘differential networks’ is sequence and expression.

For example, the CONEXIC (COpy Number and EXpression In Cancer) algorithm (Akavia et al., 2010) combines DNA copy number with gene expression levels to identify driver mutations and predict the processes they alter. The modeling assumptions underlying the data integration are: (1) A driver mutation should co-vary with a gene module involved in tumorigenesis (i.e., it assumes that the module’s expression is “modulated” by the driver); (2) Expression levels of the driver control the malignant phenotype rather than copy number (because other mechanisms may lead to similar dysregulated expression of the driver gene).

This approach predicted two new tumor dependencies in melanoma and the processes they alter. Moreover, these predictions were then confirmed using RNAi. CONEXIC thus uses gene expression as an intermediary to connect genotype to phenotype, building a cascade of events from DNA, through modulated gene expression, to tumorigenic phenotype. Anchoring the model at the DNA provided support for causality of influence between driver and module, although this influence can still be indirect by a cascade of unknown mechanisms.

While such modeling approaches have only recently taken hold in cancer genomics, these have been developing in genetic association for a few years. Chen and colleagues identified gene networks that are perturbed by quantitative trait loci (QTL), which in turn lead to metabolic disease (Chen et al., 2008). A single comprehensive computation locates the QTL, how it perturbs the molecular network, and in turn leads to variation in disease traits. As more data types that capture the “state” of the network are collected (e.g. metabolite concentrations using mass-spec), these “differential-network” (Principle 3) approaches will lead to increasingly mechanistic and causal models of disease.

Although this strategy can be applied to any process or disease, cancer is particularly suited for these approaches because somatic mutations driving tumorigenesis typically have large impact on multiple genes and cellular processes, and thus, their effect is more easily detected. Disease genes based on germ-line mutations that persist though the powerful evolutionary filters are typically more subtle and harder to detect; indeed, disease is frequently invoked only by the combinatorial interaction of many genes.

As proof of concept of “personalized medicine” and using yeast as a model system, CAMELOT (Causal Modeling with Expression Linkage for cOmplex Traits) (Chen et al., 2009) integrated genotype and gene expression levels (measured prior to drug exposure) to quantitatively predict drug sensitivity. Applying a differential network approach, a small number of causative genes are identified and then used to build regression models to predict drug response for each yeast strain. The algorithm faithfully predicted both the causal genes (24/24 predictions validated) and drug response. Although epistatic relations existed between genes, the statistical simplicity of linear models led to more robust and accurate models from data. We anticipate that a comparable dataset from patient tumors (including genotype, basal gene expression, and quantitative drug response) could be used to rationally select each individual patient’s drug treatment, essentially customizing and optimizing patient care.

Strategy 5: Integration of single cell data to account for cell to cell heterogeneity

Whereas the measurements discussed thus far were taken over population aggregates using bulk assays, most signal processing occurs at the level of the individual cell. Over the past decade, studies have repeatedly demonstrated a large degree of heterogeneity between individual cells, even within clonal populations. This variation arises from differences in protein concentrations and stochastic fluctuations in biochemical reactions involving molecules with low copy numbers. A common finding is that a response appears dose dependent in bulk assays, but is actually an “all or nothing” response in single cells. That is, the intensity of the single cell response remains constant under dose but the fraction of the cells that respond increases with dose (e.g. NF-kB in response to TNFα) (Tay et al., 2010). In these cases, there are a number of distinct sub-populations, and no individual cell behaves in accordance with the population average. Such sub-populations confound network inference algorithms when two molecules exhibit statistical dependency at the population level, but actually reside in mutually exclusive cells.

Heterogeneity of molecules at the single cell level can have crucial functional impact. Even clonal cell lines treated with drugs under carefully controlled conditions exhibit a large, previously unappreciated, degree of variation in cell survival and other parameters (Cohen et al., 2008). A bulk growth assay can mask a small sub-population of drug-resistant cells, which can later form a drug resistant tumor. While much debate still exists regarding the origins and emergence of these sub-populations, it is clear such populations often exist in tumors. For example, Sharma and colleagues identified a drug tolerant state that can be transiently acquired and relinquished through reversible epigenetic changes that occur at low frequency (Sharma et al., 2010b). Therefore, to model drug response in tumors, it is vital to observe the system at the single cell level and take heterogeneity (stochastic, genetic and micro-environment) into account.

A unique and beneficial feature of single cell data is the simultaneous observation of multiple signaling proteins in each individual cell. The stochastic variation observed across individual cells can be harnessed as a data-rich source for network inference, in which each of many thousands of cells can be treated as an individual sample (Sachs et al., 2005). This strategy provides significantly more samples than available in bulk assays (e.g. each microarray is only a single sample).

Nevertheless, this amount of data comes with a technical tradeoff. To identify interactions and their function, the participating signaling proteins need to be measured simultaneously in the same sample. Typically, single cell measurement technologies are limited to a small number of simultaneous channels (~4–10 channels for flow cytometry and ~3 channels for microscopy) with microscopy having the unique advantage of real-time tracking across space and time. A promising emerging technology is mass spectrometry-based single cell cytometry (Ornatsky et al., 2008), which currently can measure up to 35 antibodies in a single cell, with the potential scale up to 100. This approach will likely break new ground by enabling the study of mid-scale networks in individual cells. We hope and must rely on clever chemists, engineers and physicists to take on this important challenge of measuring many molecular states in live, single cells over time and space.

In the meantime, computational approaches can help bridge the gap by: (1) pointing to a small number of key components in a differential-network, which would be valuable to analyze at the single cell level; and, (2) stitching together small, overlapping sub-networks into larger network models (Sachs et al., 2009). But there remains a need to develop methods for integrating genomic data sets at the population level with single cell measurements over small subsets of components at critical network junctures, leading to a more accurate model of the underlying cellular computations.

Strategy 6: Using perturbations to reveal network wiring

To infer network models that describe how a network responds to stimuli, as well as through what molecular interactions and mechanisms this sensing and response occurs, comprehensive profiles must be measured following perturbations. We consider three methods to perturb the system: RNAi, drugs, and natural variation. As this strategy is still under development, this section is more speculative.

Measuring network behavior following an RNAi perturbation uncovers the functions of a gene and provides definitive causal links between network components. A key strength of RNAi is that it can be used effectively to target any desired gene. However, RNAi also has limitations due to its slow kinetics and potential non-specific cellular responses (e.g., innate immune response to double stranded RNA or overloading of the RNAi machinery and off-target effects). Using RNAi-based perturbations followed by comprehensive measurements, Amit et al. (2009) recently developed a network model of transcriptional regulation in the pathogen-sensing response (Amit et al., 2009). Candidate regulators and a reduced signature response were first selected from microarray data of cells stimulated with pathogens. Each candidate was then knocked down with RNAi, and the effect on the signature was quantified. This strategy uncovered many new factors involved in pathogen-sensing and generated an informative network wiring diagram that revealed new cross-talk and feedback in these pathways. This strategy and its variations should succeed in reconstructing medium-size molecular networks in other systems.

A second perturbation to consider is small molecules, which often have unique and valuable properties for network modeling and direct relevance to patient care. First, in contrast to RNAi kinetics, the instantaneous action of small molecules allows for accurate control of both dose and timing, leading to simpler interpretations of its effects, without the need to consider network adaptation. Second, small molecules can have specific biochemical effects on proteins, leading to elimination of edges in the network, rather than entire nodes as RNAi does. By comprehensive monitoring of the resulting changes in the network upon drug perturbation, we can refine network models, and importantly, discover how pathway activation, cross-talk, and feedback differ across individual tumors with variable levels of drug sensitivity.

Third, variation in the DNA across individuals is a powerful resource for studying the effects of perturbation on network function. It is also effective for detecting regulatory interactions, uncovering complex phenotypes, and inferring networks (Lee et al., 2006). In contrast to deliberate and somewhat dramatic disruption of a gene’s function through RNAi or drugs, more subtle effects, such as the attenuation or alteration of function, can be observed in genetically divergent individuals. Natural variation provides us with numerous genetic alterations in various combinations, as selected by evolution to produce functional pathways. By monitoring functional pathways in action, we can infer how network components work together under different conditions. Each individual’s genetic variation provides distinct information linking genotype and phenotype and helps explain network behavior.

What still needs to be developed is an integrated experimental-computational strategy that combines stimulations and perturbations with functional measurements from the same cells to build network models. Variation in stimuli and environment allow us to derive what the network is computing, and perturbations to its components elucidate how the network is computing. This suggests expanding the framework set forth by Amit and colleagues (Amit et al., 2009) to additional dimensions, including a time series of gene expression and proteomic measurements, following each combination of stimuli and perturbations. Natural variation between individuals and tumors combined with targeted perturbations using RNAi or drugs will provide particularly powerful data for deriving tumor network models.

Executing the experimental design proposed above requires technological developments. Much of the dynamics occurs at the level of proteins and their modifications, raising the need for high throughput proteomics to measure protein abundances and activity states. Importantly, the proposed design requires assaying a prohibitively large number of samples. To make significant progress in the understanding of molecular networks, there is a critical need for the development of more economical, multiplex functional assays that can measure thousands of molecular species per sample at low sample cost. An iterative approach, in which computational modeling with existing data guides the selection of the next set of experiments, will provide the most cost-effective design (Figure 2).

New experimental technologies are rapidly progressing, with computational efforts lagging behind. For example, generating transcriptome sequence reads is easy, but their assembly remains challenging. To utilize the enormous potential of the data-types delineated above, significant advances in computational modeling is required. Specifically, there is need for a transition from static and qualitative models, to temporal and quantitative models.

Future: Personalized Cancer Medicine

Networks govern fundamental processes, such as the development of a multi-cellular organism from a single cell and communication between immune cells in a response to a pathogen. Fueled by technology and computation, research in the coming decade is expected to unravel the details and principles behind diverse molecular networks and how they compute life’s functions. For example, the ongoing revolution that has enabled the sequencing of individuals provides the first opportunities to systematically study and explain how DNA variation results in our phenotypic diversity. Reaching these goals, however, will also necessitate a deeper understanding of the biophysical principles underlying signal processing in small biological circuits and how these come together in systems of increasing size and complexity.

Within cancer research, systems biology is dramatically advancing our mechanistic understanding of tumor progression and the design of personalized therapeutics. Continued success, however, will depend on critical advances in both experimental and computational methods. Improvements in tools for measurement - especially mass spectrometry and cost-effective multiplex detection- and perturbation -especially RNAi and small molecules- will fill in our understanding of the many molecular layers that underly networks function. On the computational end, the key bottleneck is the development of validated computational methods that integrate heterogeneous data and build “differential-network” models on a per tumor basis. These methods are required to: (1) identify the genetic aberrations and the master regulators that drive proliferation, survival, metastasis, and drug resistance; (2) model the adaptive/feedback mechanisms that thwart the efficacy of potent drugs; and (3) predict additional target pathways for combinatorial drug treatment. Based on these predictions, more data can be collected to refine the models in iterative rounds of computation and experiments. As three-dimensional models of cancer (Ridky et al., 2010) continue to develop, we can also profile multiple cell types in a tumor environment and model the interactions between these. In short, these studies should teach us what drives cancers and what part of the networks we should target, both initially and after the network adapts and mutates.

Many of us believe that the ultimate solutions to minimizing cancer reside in the regime of combinatorial patient-specific drug therapy, immunotherapy, and gene therapy. Accurate quantitative models of tumor networks should predict the effects of drug perturbations and thus enable sophisticated rational therapy with optimized dosage, timing, and drug combination for each individual tumor. Drug combinations can address feedback and network adaptation, ensuring shut-down of the necessary pathways. Additionally, drug combinations can target distinct sub-populations within a tumor.

Tumor networks are armed with the ability to adapt and rapidly evolve and thus, are a powerful adversary. These need to be met with equally sophisticated and flexible therapy regimes that can track these adaptations and dynamically adapt over time, placing us several moves ahead of the tumor. Studying the emergence of drug resistance both in vitro (Johannessen et al., 2010) and in vivo can better inform methods to anticipate potential paths of resistance. The ultimate therapies would involve sending “networks” in vivo to track tumor behavior and control the dosage and timing of drug release in response to tumor behavior. This long-term goal should become feasible as the fields of network biology, synthetic biology, and appropriate drug delivery methods mature. In the immediate future, however, our goal should be to anticipate and monitor real-time changes in the tumor’s network and adapt our therapies accordingly.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akavia UD, Litvin O, Kim J, Sanchez-Garcia F, Kotliar D, Causton HC, Pochanard P, Mozes E, Garraway LA, Pe’er D. An integrated approach to uncover drivers of cancer. Cell. 2010;143:1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit I, Citri A, Shay T, Lu Y, Katz M, Zhang F, Tarcic G, Siwak D, Lahad J, Jacob-Hirsch J, et al. A module of negative feedback regulators defines growth factor signaling. Nat Genet. 2007;39:503–512. doi: 10.1038/ng1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit I, Garber M, Chevrier N, Leite AP, Donner Y, Eisenhaure T, Guttman M, Grenier JK, Li W, Zuk O, et al. Unbiased reconstruction of a mammalian transcriptional network mediating pathogen responses. Science. 2009;326:257–263. doi: 10.1126/science.1179050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay S, Chiang CY, Srivastava J, Gersten M, White S, Bell R, Kurschner C, Martin CH, Smoot M, Sahasrabudhe S, et al. A human MAP kinase interactome. Nat Methods. 2010;7:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso K, Margolin AA, Stolovitzky G, Klein U, Dalla-Favera R, Califano A. Reverse engineering of regulatory networks in human B cells. Nat Genet. 2005;37:382–390. doi: 10.1038/ng1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beroukhim R, Mermel CH, Porter D, Wei G, Raychaudhuri S, Donovan J, Barretina J, Boehm JS, Dobson J, Urashima M, et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature. 2010;463:899–905. doi: 10.1038/nature08822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm JS, Zhao JJ, Yao J, Kim SY, Firestein R, Dunn IF, Sjostrom SK, Garraway LA, Weremowicz S, Richardson AL, et al. Integrative genomic approaches identify IKBKE as a breast cancer oncogene. Cell. 2007;129:1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau R, Facciotti MT, Reiss DJ, Schmid AK, Pan M, Kaur A, Thorsson V, Shannon P, Johnson MH, Bare JC, et al. A predictive model for transcriptional control of physiology in a free living cell. Cell. 2007;131:1354–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos PD, Zhang XH, Nadal C, Shu W, Gomis RR, Nguyen DX, Minn AJ, van de Vijver MJ, Gerald WL, Foekens JA, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to the brain. Nature. 2009;459:1005–1009. doi: 10.1038/nature08021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carracedo A, Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, Rojo F, Salmena L, Alimonti A, Egia A, Sasaki AT, Thomas G, Kozma SC, et al. Inhibition of mTORC1 leads to MAPK pathway activation through a PI3K-dependent feedback loop in human cancer. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3065–3074. doi: 10.1172/JCI34739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carro MS, Lim WK, Alvarez MJ, Bollo RJ, Zhao X, Snyder EY, Sulman EP, Anne SL, Doetsch F, Colman H, et al. The transcriptional network for mesenchymal transformation of brain tumours. Nature. 2010;463:318–325. doi: 10.1038/nature08712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter H, Chen S, Isik L, Tyekucheva S, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Karchin R. Cancer-specific high-throughput annotation of somatic mutations: computational prediction of driver missense mutations. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6660–6667. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BJ, Causton HC, Mancenido D, Goddard NL, Perlstein EO, Pe’er D. Harnessing gene expression to identify the genetic basis of drug resistance. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:310. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Zhu J, Lum PY, Yang X, Pinto S, MacNeil DJ, Zhang C, Lamb J, Edwards S, Sieberts SK, et al. Variations in DNA elucidate molecular networks that cause disease. Nature. 2008;452:429–435. doi: 10.1038/nature06757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AA, Geva-Zatorsky N, Eden E, Frenkel-Morgenstern M, Issaeva I, Sigal A, Milo R, Cohen-Saidon C, Liron Y, Kam Z, et al. Dynamic proteomics of individual cancer cells in response to a drug. Science. 2008;322:1511–1516. doi: 10.1126/science.1160165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Saidon C, Cohen AA, Sigal A, Liron Y, Alon U. Dynamics and variability of ERK2 response to EGF in individual living cells. Mol Cell. 2009;36:885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert BL, Pretz J, Bosco J, Chang CY, Tamayo P, Galili N, Raza A, Root DE, Attar E, Ellis SR, et al. Identification of RPS14 as a 5q- syndrome gene by RNA interference screen. Nature. 2008;451:335–339. doi: 10.1038/nature06494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, O’Dwyer PJ, Lee RJ, Grippo JF, Nolop K, et al. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809–819. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman N, Linial M, Nachman I, Pe’er D. Using Bayesian networks to analyze expression data. J Comput Biol. 2000;7:601–620. doi: 10.1089/106652700750050961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzel M, Huang S, Koster J, Ora I, Lakeman A, Caron H, Nijkamp W, Xie J, Callens T, Asgharzadeh S, et al. NF1 is a tumor suppressor in neuroblastoma that determines retinoic acid response and disease outcome. Cell. 2010;142:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irish JM, Hovland R, Krutzik PO, Perez OD, Bruserud O, Gjertsen BT, Nolan GP. Single cell profiling of potentiated phospho-protein networks in cancer cells. Cell. 2004;118:217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannessen CM, Boehm JS, Kim SY, Thomas SR, Wardwell L, Johnson LA, Emery CM, Stransky N, Cogdill AP, Barretina J, et al. COT drives resistance to RAF inhibition through MAP kinase pathway reactivation. Nature. 2010;468:968–972. doi: 10.1038/nature09627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Land H, Parada LF, Weinberg RA. Tumorigenic conversion of primary embryo fibroblasts requires at least two cooperating oncogenes. Nature. 1983;304:596–602. doi: 10.1038/304596a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SI, Pe’er D, Dudley AM, Church GM, Koller D. Identifying regulatory mechanisms using individual variation reveals key role for chromatin modification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14062–14067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601852103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvin O, Causton HC, Chen BJ, Pe’er D. Modularity and interactions in the genetics of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6441–6446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810208106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo B, Cheung HW, Subramanian A, Sharifnia T, Okamoto M, Yang X, Hinkle G, Boehm JS, Beroukhim R, Weir BA, et al. Highly parallel identification of essential genes in cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20380–20385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810485105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher CA, Kumar-Sinha C, Cao X, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Han B, Jing X, Sam L, Barrette T, Palanisamy N, Chinnaiyan AM. Transcriptome sequencing to detect gene fusions in cancer. Nature. 2009;458:97–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani KM, Lefebvre C, Wang K, Lim WK, Basso K, Dalla-Favera R, Califano A. A systems biology approach to prediction of oncogenes and molecular perturbation targets in B-cell lymphomas. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:169. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network CGAR. Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng SB, Buckingham KJ, Lee C, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, Dent KM, Huff CD, Shannon PT, Jabs EW, Nickerson DA, et al. Exome sequencing identifies the cause of a mendelian disorder. Nat Genet. 2010;42:30–35. doi: 10.1038/ng.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo VN, Young RM, Schmitz R, Jhavar S, Xiao W, Lim KH, Kohlhammer H, Xu W, Yang Y, Zhao H, et al. Oncogenically active MYD88 mutations in human lymphoma. Nature. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nature09671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, Lane H, Hofmann F, Hicklin DJ, Ludwig DL, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates Akt. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornatsky OI, Lou X, Nitz M, Schafer S, Sheldrick WS, Baranov VI, Bandura DR, Tanner SD. Study of cell antigens and intracellular DNA by identification of element-containing labels and metallointercalators using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2539–2547. doi: 10.1021/ac702128m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pe’er D, Regev A, Elidan G, Friedman N. Inferring subnetworks from perturbed expression profiles. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(Suppl 1):S215–224. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.suppl_1.s215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, Shokat KM, Rosen N. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464:427–430. doi: 10.1038/nature08902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridky TW, Chow JM, Wong DJ, Khavari PA. Invasive three-dimensional organotypic neoplasia from multiple normal human epithelia. Nat Med. 2010;16:1450–1455. doi: 10.1038/nm.2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs K, Itani S, Carlisle J, Nolan GP, Pe’er D, Lauffenburger DA. Learning signaling network structures with sparsely distributed data. J Comput Biol. 2009;16:201–212. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2008.07TT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs K, Perez O, Pe’er D, Lauffenburger DA, Nolan GP. Causal protein-signaling networks derived from multiparameter single-cell data. Science. 2005;308:523–529. doi: 10.1126/science.1105809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E, Shapira M, Regev A, Pe’er D, Botstein D, Koller D, Friedman N. Module networks: identifying regulatory modules and their condition-specific regulators from gene expression data. Nat Genet. 2003;34:166–176. doi: 10.1038/ng1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira SD, Gat-Viks I, Shum BO, Dricot A, de Grace MM, Wu L, Gupta PB, Hao T, Silver SJ, Root DE, et al. A physical and regulatory map of host-influenza interactions reveals pathways in H1N1 infection. Cell. 2009;139:1255–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SV, Haber DA, Settleman J. Cell line-based platforms to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of candidate anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010a;10:241–253. doi: 10.1038/nrc2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SV, Lee DY, Li B, Quinlan MP, Takahashi F, Maheswaran S, McDermott U, Azizian N, Zou L, Fischbach MA, et al. A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell. 2010b;141:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens PJ, McBride DJ, Lin ML, Varela I, Pleasance ED, Simpson JT, Stebbings LA, Leroy C, Edkins S, Mudie LJ, et al. Complex landscapes of somatic rearrangement in human breast cancer genomes. Nature. 2009;462:1005–1010. doi: 10.1038/nature08645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay S, Hughey JJ, Lee TK, Lipniacki T, Quake SR, Covert MW. Single-cell NF-kappaB dynamics reveal digital activation and analogue information processing. Nature. 2010;466:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nature09145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Saito M, Bisikirska BC, Alvarez MJ, Lim WK, Rajbhandari P, Shen Q, Nemenman I, Basso K, Margolin AA, et al. Genome-wide identification of post-translational modulators of transcription factor activity in human B cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:829–839. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir BA, Woo MS, Getz G, Perner S, Ding L, Beroukhim R, Lin WM, Province MA, Kraja A, Johnson LA, et al. Characterizing the cancer genome in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2007;450:893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature06358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst AW, Bodemann BO, Cardenas J, Ferguson D, Girard L, Peyton M, Minna JD, Michnoff C, Hao W, Roth MG, et al. Synthetic lethal screen identification of chemosensitizer loci in cancer cells. Nature. 2007;446:815–819. doi: 10.1038/nature05697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]