Abstract

The incidence of obesity is increasing at an alarming rate. There is compelling evidence that obesity increases the risk of preeclampsia about 3-fold, and in developed countries is the leading attributable risk for the disorder. In this presentation we explore this relationship and propose targets for future studies guided by the much more extensively studied relationship of obesity to cardiovascular disease. We further address the hypothesis that asymmetric dimethyl arginine (ADMA), an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, may be one convergence point for the mechanism by which obesity increases the risk of preeclampsia. We conclude with consideration of the clinical implications of this information.

Introduction

Obesity is a major epidemic in developed countries that is now extending to developing countries.1 In the USA in the last 30 years, the percentage of women who are obese (BMI > 30) or overweight (BMI > 25) has increased almost 60%.2 The relationship of obesity to increase Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease is well recognized. However, obesity also has important implications for pregnancy outcomes. In addition to “mechanical issues” associated with morbid obesity there is an increased frequency of other adverse outcomes. Of these, the best studied is preeclampsia. In a study based on the pregnant population in Pittsburgh we found a three-fold increase in the risk of preeclampsia associated with obesity3.

Understanding how obesity increases the risk of preeclampsia is important for several reasons. First it appears that obesity is the leading attributable risk for preeclampsia in the United States, present in 30% of cases.3 Since the obvious cure for obesity, weight loss, is not an appropriate strategy during pregnancy and minimally successful outside of pregnancy, identifying targets that might reduce the impact of obesity to increase the risk of preeclampsia would be quite useful. Further, in contrast to other risk factors for preeclampsia, it would seem that mechanistic insights gained about the role of obesity to contribute to preeclampsia are more likely to be relevant to the general population.

This presentation will detail the impact of obesity to increase the risk of preeclampsia. We will also examine possible mechanisms by which obesity might contribute to the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Preeclampsia and later life cardiovascular disease share common risk factors, including obesity. In addition the disorders share many pathophysiological features including endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and increased inflammatory activation.4 Furthermore, preeclampsia is associated with an increased risk of later life cardiovascular disease.5, 6 Since information on the mechanisms by which obesity increases the risk of preeclampsia is limited, we will be guided by the large body of information available for cardiovascular disease as we address potential mechanisms for preeclampsia. With this background, we will identify useful targets for the study of the role of obesity in preeclampsia. We will also explore a specific hypothesis that the endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), might be a convergence point for many of the potential mechanisms by which obesity increases preeclampsia risk. Finally we address the potential clinical implications of these insights.

Evidence for the role of obesity in preeclampsia

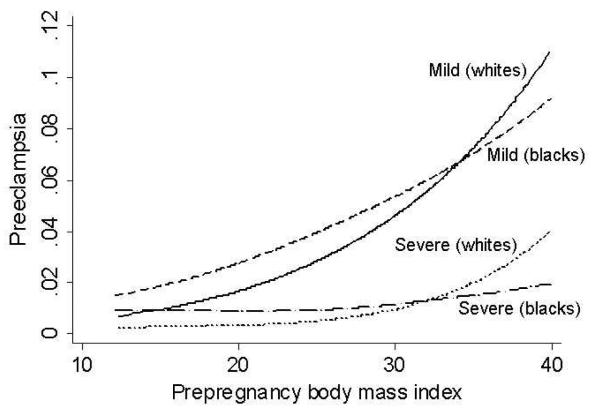

Obesity increases the risk of all “forms” of preeclampsia. Thus, the risk of severe and mild preeclampsia7 and preeclampsia occurring in early and late gestation8 are greater in obese and overweight women. The increased risk is also present for whites and blacks although the impact may be slightly greater in whites(Figure 1).7 The relationship that obesity increases the risk of preeclampsia has been reported for several populations around the world indicating that this is not a phenomenon limited to western societies.9-11 It is also evident that this relationship is not limited to obese and overweight women because increases in BMI in the normal range is also associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia.3 The likelihood suggested by this, that fat mass is important, is supported by findings that weight loss reduces preeclampsia risk.12, 13

Figure 1. Prepregnancy BMI is associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia.

Data from the Perinatal Collaborative Study including more than 19,000 Black and 19,000 white women was analyzed and the unadjusted prevalence of preeclampsia as related to prepregnancy BMI presented7. The prevalence of preeclampsia increased with increasing prepregnancy BMI for mild and severe preeclampsia and in blacks and whites.

In the Pittsburgh population the 3-fold increase risk in preeclampsia in obese women translates into a 30% attributable risk. Nonetheless, despite the increased risk, a 3-fold increase with obesity predicts that only about 10% of obese women will develop preeclampsia. Although this is a substantial risk, 90% of obese women do not develop preeclampsia. Determining what is different about obese women who develop preeclampsia and those who do not could provide valuable insights.

Mechanisms by which obesity increases the risk of preeclampsia

Total body fat, distribution and accrual

In examining the reason why some but not all obese women develop preeclampsia it is important to bear in mind that adiposity appears to be the issue and that BMI is an imperfect surrogate for adiposity. Measures of body composition, including percent body fat, may very likely identify the obese woman at risk of preeclampsia more accurately. Several strategies allow determination of percent body fat.14 These include water or air displacement or the measurement of bioelectrical impedance (BEI). Of these BEI is most practical for large populations. However, BEI measurements actually determine total body water, which is related to total body fat.15 However, the relationships of BEI to total body water, and of total body water to percent body fat are different in pregnancy and change as gestation progresses. Thus, BEI machines with built in algorithms to translate BEI to percent body fat based on non-pregnant standards will not provide meaningful data in pregnancy. Fortunately, pregnancy specific algorithms are available15, 16 and if “raw data” can be accrued by BEI and the appropriate variables measured these formulas can be used to determine percent body fat. Thus far little of such data is available.

It is also evident from the cardiovascular literature that it is not just fat but fat distribution that is important. Central obesity as a marker of visceral obesity presents much higher risk than peripheral obesity.17 Visceral fat is functionally different than subcutaneous fat. It produces more CRP and inflammatory cytokines18 and less leptin19 and contributes more to oxidative stress. Additionally, since visceral fat drains directly to the liver the influence on hepatic function and response are greater for this adipose tissue bed. Drainage from visceral fat can up regulate the hepatic production of lipids, acute phase reactants and inflammatory cytokines. This is reflected in the increased circulating concentrations of CRP, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) and inflammatory cytokines in individuals with visceral obesity.20

Another open question is the relevance of fat accrual to the genesis of preeclampsia. Although in general obese women gain less weight than women who are not obese,21 the relationship of fat accrual to outcome has not been fully investigated. Furthermore, this relationship cannot be tested easily in preeclampsia. Numerous studies indicate increased weight gain in women who subsequently develop preeclampsia.22 However, the impact of weight gain in women who subsequently develop preeclampsia is as likely related to fluid retention associated with preeclampsia as it is to fat accrual. Again the answer would be to directly assess of fat mass accrual but this has not yet been reported.

Relevance of metabolic changes associated with obesity

Obesity is associated with profound metabolic and physiological changes. Adipose tissue is not an inert fat store but rather a hormonally active tissue, producing cytokines, as well as active materials produced predominantly in fat tissue, the adipokines.23 These materials result in the association of obesity with increased inflammation, insulin resistance and the insulin resistance syndrome and oxidative stress.20, 24 Although mean values of the concentration of these materials will be increased in groups of obese women it will not be increased similarly in all women. For example, insulin resistance, a prominent metabolic abnormality of obesity is present in only two thirds of obese women.25 Perhaps it is only obese women at the extremes of abnormal values who are at risk. We will detail the relevant metabolic and physiological changes of obesity with this concept in mind.

Insulin Resistance

Insulin resistance is more common in preeclampsia26 and can be demonstrated in individuals long after a preeclamptic pregnancy.27 Insulin resistance is present in two thirds of obese individuals and in about 7% of lean individuals.25 It is tempting to consider insulin resistance as the only metabolic change in obesity responsible for the increased risk of preeclampsia. However, this is not the case with respect to the relationship of cardiovascular disease and Type II diabetes to obesity and insulin resistance. In individuals who are insulin resistant, there is an increased risk for cardiovascular disease as well as Type II diabetes. This relationship is independent of whether the individual is lean or obese. However, in obese individuals and lean individuals with equivalent insulin resistance, Type II diabetes still develops more frequently in obese individuals, indicating that the effect of obesity to increase morbidity is due to more than insulin resistance.25 Animal experiments have shown that adipose accrual reduces vasorelaxation to endothelium-dependent vasodilators before the development and independently from insulin resistance, but in association with increased tissue oxidative stress/vascular tyrosine nitration.28 Nonetheless, insulin resistance is a key feature directing risk and is very important given that obese individuals who were not insulin resistant did not have an increase in cardiovascular risk or Type II diabetes. It is likely a similar relationship is present with obesity and preeclampsia.

Metabolic (Insulin resistance) Syndrome

The metabolic syndrome was originally described as consisting of obesity, hypertension, insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance and dyslipidemia. This syndrome strikingly increases risk for cardiovascular disease. It is probably more appropriately termed the insulin resistance syndrome as resistance to the metabolic effects of insulin can explain all of the features.29 The associated obesity is posited to lead to hypertension through (1) reduced availability of NO secondary to increased ADMA and oxidative stress, (2) increased sympathetic tone and (3) increased expression of angiotensinogen by adipose tissue (least well established).29 Preeclampsia manifests the findings of the metabolic syndrome and women with a history of preeclampsia are more likely to have the metabolic syndrome than women with prior normal pregnancies.30

The dyslipidemia of the metabolic syndrome and obesity may be causally relevant. Obesity is associated with elevated triglycerides, free fatty acids and reduced HDL.31 LDL cholesterol is slightly elevated or normal, but small, dense atherogenic LDL particles are usually more abundant.31 High levels of free fatty acids are released by adipocytes. The increase in plasma free fatty acids is especially relevant as fatty acids can induce oxidative stress and also directly contribute to insulin resistance.32 For many years the lipid hypothesis of atherogenesis posited abnormal lipids, further modified by oxidative stress, as the prime mechanism for the vascular injury associated with the metabolic syndrome.33 Although attention is now focused on inflammation as a major factor in the genesis of coronary artery disease, it is still quite likely that oxidative modification of especially small dense LDL is an important component of vascular injury, especially the formation of atheromatous plaque. Inflammation would contribute to this process by the formation of reactive oxygen species. Preeclampsia shares an identical dyslipidemia to that of obesity. In our prior studies of lipids there was a wide scatter of lipid concentrations in women with preeclampsia. Perhaps it is obese women with the most abnormal lipids who are at increased risk of preeclampsia.

Inflammation

Inflammation is another feature of obesity relevant to cardiovascular disease. Adipose tissue produces several inflammatory mediators that can act to alter endothelial function. It is interesting that the majority of these mediators seem to be made more actively in adipose tissue from obese individuals; that is, the production is not greater simply because of more tissue but because of inherent differences in the adipocyte with obesity.20

The role of inflammation in cardiovascular diseases is indicated by increased concentrations of inflammatory markers. Several of these are also increased in preeclampsia. C-reactive protein is an acute phase reactant originally thought to be made exclusively by the liver.20 More recent data indicates production in adipose tissue. CRP is higher in obese individuals and predicts both worse cardiovascular outcomes and cardiovascular morbidity.20 CRP is also elevated in early pregnancy in women who later develop preeclampsia.34 Studies from our group indicate that CRP is more associated with preeclampsia in obese women than lipids and could account for about one third of the relationship between BMI and the risk of preeclampsia.35

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) is produced in adipose tissue.36 It is produced as a locally acting agent (membrane bound) by adipocytes and as a circulating hormone by macrophages resident in adipose tissue.24 It increases insulin resistance, activates endothelial cells and can generate oxidative stress. TNFα is higher in obesity and may contribute to insulin resistance in obesity. TNFα is also elevated in preeclampsia37, 38 possibly from adipose tissue as placental mRNA is not increased.39 Although appealing as a mechanism by which obesity might increase the risk of preeclampsia, recent studies indicate TNFα is not higher in obese pregnant women compared to non-obese women.40, 41

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) is higher with obesity42 and is also in preeclampsia.43 The IL-6 produced in adipose tissue accounts for 30% of circulating IL-6.24 IL-6 is associated with later life cardiovascular disease and with an increased risk of insulin resistance.24 It is a major stimulator of acute phase reactants with consequent effects on vessel wall function and blood clotting. IL-6 has been proposed as a major mediator of inflammation induced vascular damage.44

Oxidative Stress

Obesity is accompanied by oxidative stress. The origin of oxidative stress is proposed to be secondary to increased free fatty acids and inflammation.29 It is also suggested that diet can contribute to oxidative stress. Obese individuals have lower blood concentrations of antioxidants.45, 46 This could be due to reduced dietary intake of antioxidants, but increased consumption by reactive oxygen species is also possible. Ingestion of large quantities of fats or carbohydrates is associated with increased generation of leukocyte free radicals.29 Interestingly, this dietary pattern is more prevalent with obesity and during pregnancy in women who develop preeclampsia.47

Adipokines

Adipose tissue produces agents that profoundly affect metabolism. Two of these, leptin and adiponectin, have been related epidemiologically and mechanistically with cardiovascular disease.48

Leptin was initially discovered as the appetite suppressant hormone that was absent in the genetically obese ob/ob mouse. Leptin was soon recognized to have metabolic effects to increase lipolysis and beta-oxidation.49 Obese individuals are leptin resistant. Thus, obesity is associated with increased leptin and not surprisingly leptin correlates with insulin resistance. Leptin is a predictor of cardiovascular risk that is, nonetheless, independent of insulin resistance.50, 51 Leptin has cytokine-like functions to activate endothelial cells.52 It is increased with inflammation, correlating with markers of inflammation and activates monocytes in vitro.20 Leptin has central actions to stimulate sympathetic outflow which is proposed to increase blood pressure.53 Leptin has been suggested as directly involved in atherosclerosis and hypertension.50, 53 The placenta produces leptin with message concentration approaching that present in adipose tissue.54, 55 Maternal leptin, probably of placental origin, is increased in preeclampsia.27, 56-60 Nonetheless, even in late pregnancy when leptin is highest, leptin still correlates with maternal BMI.

Adiponectin is produced in fat and has an insulin sensitizing effect. It increases free fatty acid oxidation and reduces serum free fatty acids, triglyceride and glucose concentrations. It inhibits TNFα induced monocyte adhesion and adhesion molecule expression.24 Genetic polymorphisms, which decrease circulating adiponectin, are associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease.24 Adiponectin is decreased with obesity and this has been suggested to have a potentially atherogenic effect. In addition, certain cytokines can reduce adiponectin concentration.

Interestingly, despite the insulin resistance associated with preeclampsia, circulating concentrations of adiponectin are not established as reduced. Most early studies reported higher concentrations of adiponectin in women with preeclampsia.61-64 In the last few years it has been appreciated that adiponectin circulates in several forms and the most active in inducing insulin sensitivity are high molecular weight oligomers. Although there are reports that these forms are lower in preeclampsia65 there are also reports they are higher 66, 67 and this apparent paradox awaits resolution.

Angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors

The soluble receptor for placental growth factor (PlGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), sFlt1, are elevated in women with preeclampsia up to 5 weeks prior to evident clinical findings.68 It is proposed and supported by experimental data that this soluble receptor serves as an antagonist to the action of VEGF and PlGF.69 Another relevant antagonist, soluble endoglin, which serves as an antagonist to the angiogenic factor TGFβ, is also increased in women with and before preeclampsia. Obesity is associated with increased circulating angiogenic factors including VEGF. This likely represents spill over from production by adipose tissue especially visceral fat.70 Because of the high circulating concentration of sFlt1 in pregnancy VEGF is virtually absent in the blood of pregnant women. In contrast to VEGF, PlGF is measurable in pregnancy and is significantly lower in mid-pregnancy in overweight and obese women, and this relationship is evident in women who develop preeclampsia as well as women with uncomplicated pregnancies.71 The explanation for this decrease in PlGF in obese women during pregnancy is unclear, but it does not seem to be directly related to differences in sFlt1 since this factor is not different between lean and obese pregnant women, and sFlt1 is not different at the time PlGF is observed to be significantly lower.

Life style factors associated with obesity

Several life style factors associated with obesity influence the risk of cardiovascular disease. The association of diet, sleep disorders and physical activity with cardiovascular disease is well established. There is much less information available for the relevance of these factors to preeclampsia. We present evidence for the involvement of life style in cardiovascular disease and its relationship to obesity. We also review the limited data available on the role of these factors in preeclampsia. We posit that the risk for preeclampsia in an obese woman may also be influenced by these lifestyle factors.

Diet

Poor nutrition is a major contributor to cardiovascular disease. Diets high in antioxidants, fruits and vegetables, B vitamins, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), fish and seafood, whole grains, and dietary fiber protect against heart disease, and excessive intakes of saturated fat, trans fatty acids, refined grains and sweets increase the risk of heart disease.72 After decades of research in this area, healthy diet is now a cornerstone of cardiovascular disease prevention.

Despite the similarities between preeclampsia and cardiovascular disease, few investigators have studied the role of diet in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia.73 Vitamin C, vitamin E, and the carotenoids are important physiologic antioxidants. Zhang et al.74 suggested that consumption of less than the recommended amount of vitamin C and fruit and vegetable servings in the year before delivery increased the likelihood of preeclampsia. This was supported by a more recent study in which women with the highest quartile of serum vitamin C concentration at an average of 18 weeks gestation had lower rate of preeclampsia (0.59 {0.38-0.93}) than women with lower vitamin C concentration.75 Results of supplementation with vitamins C and E have not been as consistent.76,75,77 The inconsistency of the vitamin supplementation results compared to dietary studies may indicate differences in populations but likely also reflects the important difference between food intake and dietary supplementation. Folate reverses endothelial dysfunction in patients with some chronic diseases,78-81 reduces oxidative stress, and restores the activity of nitric oxide.82, 83

Fish and seafood are the major contributors of n-3 fatty acids in the diet. Preeclamptic women have lower red cell concentrations of n-3 PUFAs84 and increased trans-fatty acids.85 Observational studies of dietary n-3 PUFA intake during pregnancy have produced conflicting results.86, 87; 88 Dietary intake of trans-fatty acid or saturated fat has not been extensively studied in relationship to preeclampsia.

Foods high in refined sugars may replace nutrient-dense foods in the diet and also may have an independent role in contributing to the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Indeed, Clausen et al. reported that women who consumed >25% of energy from sucrose in the second trimester were 3.6 (1.3-9.8) times as likely as low sucrose consumers to develop preeclampsia.47 Furthermore, obesity is associated with increased intake of soft drinks,89 which in the US are sweetened with fructose. Fructose does not stimulate insulin and is associated with lower leptin concentrations.90 It can induce the metabolic syndrome in animals91 and increased intake is associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome in humans.90 It is interesting that in the Clausen study, soft drink intake accounted for much of the increased caloric intake associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia.47

All of the nutrient intakes that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease or preeclampsia are more common in obesity. Thus intakes of saturated lipids, and fructose as soft drinks are greater. 89,92 However, equally important are dietary deficiencies. Data from healthy adults and children suggest that micronutrient concentrations in blood are negatively associated with BMI and other measures of body fatness.45, 46 In a cross-sectional study of 19,068 healthy men and women, plasma ascorbic acid concentrations were inversely related to waist-to-hip ratio, even after adjusting for BMI, age, supplement use, smoking, and socioeconomic status.93 Anderson et al. conducted a prospective cohort study of 3,071 individuals in the CARDIA Study and determined that BMI at baseline predicted a lowering of serum carotenoid concentrations 7 years later in nonsmokers.94 To our knowledge, these associations have not yet been tested during pregnancy. It is possible that these dietary excesses and deficiencies drive the relationship of obesity to preeclampsia.

Physical activity

Reduced physical activity is a well-recognized and major contributor to the epidemic of obesity. There are additionally, however, other important interactions between these lifestyle factors. The independent and combined association of physical activity and body mass index with cardiovascular biomarkers have been explored in studies specifically relevant to women and indicate interaction of these life style factors on components of cardiovascular risk. In a study of exercise and obesity in women, overweight and obesity were significantly associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease (CAD), whereas increasing levels of physical activity were associated with a graded reduction in CAD risk. When a joint analyses of BMI and physical activity was conducted, with women who had a healthy weight and were physically active as the reference group, the relative risks of CAD were highest for women who were obese and sedentary 3.44, decreased to 2.48 for women who were obese but active, and decreased even more (1.48) for women who had a healthy weight but were sedentary. Similar findings were reported when the analysis was focused on waist-hip ratio and physical activity.

The similarities between later life cardiovascular disease and preeclampsia and the fact that physical conditioning and preeclampsia have opposite effects on critical physiological functions, suggest that, as with cardiovascular disease, exercise may reduce the risk of preeclampsia. The available data, although historical and observational, support this concept. Even occupational and leisure-time physical activity in early pregnancy have been associated with a reduced incidence of preeclampsia, as compared to women who are less active.95, 96 A case control study of 201 preeclamptic and 383 normotensive pregnant women assessed the type, intensity, frequency, and duration of physical activity performed during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy and during the year before pregnancy.97 Women who engaged in any regular physical activity during early pregnancy, compared with inactive women, experienced a 35% reduced risk of preeclampsia. When the level of activity was considered, those who those engaged in light or moderate activities and those who participated in vigorous activities experienced a reduced risk of 24% and 54%, respectively, relative to inactive women. Brisk walking when compared with no walking at all, was associated with a 30% to 33% reduction in preeclampsia risk. Recreational physical activity performed during the year before pregnancy was associated with similar reductions in preeclampsia risk. These data suggest that regular physical activity, particularly when performed during the year before pregnancy and during early pregnancy, is associated with a reduced risk of preeclampsia.98

It is possible that obesity is important as a surrogate for reduced physical activity. More likely, as with cardiovascular disease the interaction of obesity and reduced physical activity increases preeclampsia. This is an important target for study as perhaps modifying physical activity in obese women could reduce the risk of preeclampsia.

Sleep Disorders

Sleep disorders are associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Hypertension, coronary artery disease, stroke, arrhythmias and heart failure are all more common with disordered sleep.99 The frequency of cardiovascular disease in women increases with decreasing duration of sleep. When compared with women sleeping 8 hours a night, women sleeping 5 hours a night have 1.5 (1.1-1.9) times the risk of cardiovascular disease.100 Sleep disorders may contribute to cardiovascular disease in several ways. The most direct and well established effect is through intermittent hypoxia associated with the obstructive sleep apnea.101 In this syndrome individuals suffer intermittent airway obstruction with consequent hypoxemia during sleep. This is frequently manifested as snoring. Individuals with obstructive sleep apnea matched for BMI with individuals without this disorder have an excess of adverse cardiovascular findings including increased diastolic blood pressure, and increased dyslipidemia.102 The intermittent hypoxia is associated with oscillation of sympathetic outflow. To a certain extent the hypoxia reoxygenation resembles the hypoxia reperfusion syndrome and consistent with this resemblance is associated with free radical production.103,104 Of special relevance to the pathogenesis of preeclampsia sleep apnea is associated with biochemical evidence of endothelial dysfunction.105

However, there are likely also effects of disordered sleep other than intermittent hypoxia. Sleep dysfunction is also an independent risk factor for insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome.106 Experimentally, insulin resistance is increased in sleep deprived individuals.107 The relationship to abnormal insulin resistance persists with adjustment for BMI and manifests a dose response with insulin resistance increasing with more dysfunctional sleep.108 Alterations of autonomic input, immune function and neuroendocrine disruptions associated with fragmented sleep are also relevant.106

Obesity is the leading risk factor for sleep-disordered breathing.109-112 In adults between 30 and 69 years old 17% have disordered breathing. It is estimated that 58% of individuals with sleep disorders are obese109. The relationship of metabolic syndrome to sleep disorders suggests a feed forward interaction.113, 114

Many events in normal pregnancy affect sleep adversely with 66-94% of pregnant women describing changes in sleep patterns.115 The change in sleep during pregnancy is not extremely well studied but is likely a complex interplay of the effects of reproductive hormones on respiratory drive and “mechanical factors” related to the increasing size of the fetus and physiological changes of increased extracellular volume and edema.115, 116 The origin of the sleep abnormality varies with the duration of gestation. In early pregnancy it is primarily increased urinary frequency while as pregnancy advances other features such as difficulty in the use of usual sleep postures and gastroesophageal reflux become important. Finally, in late gestation the genesis appears to be largely due to airway obstruction. Sleep apnea, as indicated by snoring, increases to more than 50% of women (compared to 3.2% of non-pregnant controls).117 This of course is a form of sleep disorder especially relevant to cardiovascular disease including hypertension and metabolic syndrome, two of the components of the preeclampsia syndrome.

The relationship of sleep disorders to cardiovascular disease suggests that sleep disruption might also be relevant in preeclampsia. There are several lines of evidence supporting such a relationship. Snoring which is common in pregnancy is even more common in preeclampsia. Several studies have documented increased snoring in women with preeclampsia.117-120 In a study comparing preeclampsia and normal pregnancies, snoring was present in 85% of women with preeclampsia and in 55% of women with normal pregnancy outcome (p > 0.001).117 In another study in which pregnancy outcome was compared in women who did or did not snore, preeclampsia occurred in 6-7% of women who snored compared with 4% of women who did not (p < 0.05). Women with preeclampsia, gestationally age matched normal pregnant women and normal nonpregnant women were observed with overnight monitoring of sleep pattern and arterial oxygenation. With this objective assessment, women with preeclampsia had a significant doubling of time with inspiratory flow limitations compared to normal pregnant women.119

In summary, obesity increases the frequency of sleep disturbances. This is further increased by the changes of pregnancy. Pregnancy increases the risk of sleep apnea and sleep apnea is more common in preeclampsia. As with cardiovascular disease there is an increased frequency of disordered sleep in preeclampsia. It is likely that the pathophysiological changes secondary to sleep disorders contribute to the development of preeclampsia providing a mechanism by which obesity can increase preeclampsia risk.

ADMA as a convergence point for obesity related mechanisms to increase the risk of preeclampsia

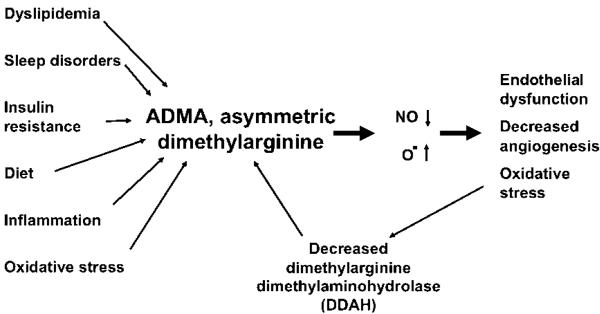

ADMA is an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase. ADMA is elevated in individuals at risk for cardiovascular disease.121-125 Virtually all of the factors that are considered risk factors for cardiovascular disease are associated with elevated ADMA. Inflammation,126 dyslipidemia,127, 128 insulin resistance,129, 130 elevated homocysteine,127, 131 and even sleep disorders,132 all are associated with increased ADMA. The pathophysiological changes induced by obesity that are relevant to cardiovascular disease or preeclampsia all would be expected to increase ADMA (Figure 2). This is supported by data demonstrating increased ADMA concentration with obesity.126, 133-135

Figure 2. Asymmetric Dimethylarginine (ADMA) has been proposed as the “Uber Risk Factor”145 where many of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease and we propose for obesity and preeclampsia converge.

Multiple risk factors can increase ADMA. Although these are shown as acting directly to increase ADMA it is most likely they act to reduce the activity the degradatory enzyme, dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH). With an increase in ADMA, nitric oxide synthase activity is competitively inhibited and the enzyme uncoupled leading to the production of superoxide. The resulting increased oxidative stress further decreases the activity of DDAH.

ADMA is a dimethylated analogue of arginine. The methylated arginines are synthesized on proteins and are only available as modified amino acids with protein breakdown. The major mechanism to modify ADMA concentration is by regulation of its degradatory enzyme, dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH). Impaired DDAH activity is a central mechanism by which cardiovascular risk factors increase ADMA and disrupt NOS activity.127, 136-144 DDAH, is regulated by oxidative stress and by inflammatory cytokines and hyperglycemia. Oxidative stress modifies a crucial sulfhydryl group in the active site of the enzyme and may be involved in the activity of some of the other factors to increase circulating ADMA.127, 130, 138, 139, 142, 144-153

ADMA appears to exert its activities through its role as an antagonist of the conversion of arginine to nitric oxide (NO) by NOS. There are two results of this antagonism. The first is reduced NO production and the second the uncoupling of NOS. ADMA “uncouples” endothelial NOS, such that molecular oxygen becomes the substrate for electron transfer rather than the guanidino nitrogen of L-arginine.154, 155 Under these conditions, endothelial NOS generates superoxide anion, increases oxidative stress, attenuates NO bioactivity, and induces additional endothelial dysfunction. Thus, ADMA is both increased by oxidative stress and by uncoupling NO has the capacity to increase oxidative stress154, 155(Figure 2).

Several studies have reported that plasma ADMA concentrations are higher in women with preeclampsia.125, 156-161 Plasma ADMA concentrations are also significantly higher in mid-pregnancy in women who later develop preeclampsia.157,162 ADMA concentrations remain high in these same women when they develop preeclampsia compared to women with an uncomplicated pregnancy and women who have growth restricted infants in the absence of developing preeclampsia.162 These data are particularly interesting given the central role ADMA plays in the regulation of endothelial-dependent vascular function, angiogenesis and arteriogenesis, and the known deficiencies in these activities in preeclampsia.

Consistent with a role for ADMA in the increased risk of cardiovascular disease and preeclampsia, circulating plasma ADMA concentrations are higher in obese subjects.126, 133-135 While the exact mechanism for the increase in plasma ADMA in with obesity is unknown, it is likely mediated in part by a change in DDAH activity. Interestingly, a recent study reported that plasma ADMA concentrations correlate positively with the acute inflammatory marker CRP in obese subjects both before and after weight loss suggesting a role for inflammation.126 In addition, ADMA is higher in obese insulin resistant women compared to similarly obese insulin sensitive women. ADMA concentrations are inversely related to insulin sensitivity, and ADMA concentrations decrease in response to weight loss.134, 135

It is possible that preeclampsia develops in obese women with the highest ADMA concentrations. As a competitive antagonist of L-arginine many of the effects of ADMA can be reversed with modest increases in L-arginine intake. Arginine at concentrations that increase NO production has been used safely in pregnancy.163-166ADMA provides targets for subsequent randomized controlled trials in obese women.

Summary and Clinical Perspectives

The evidence is compelling that obesity increases the risk of preeclampsia and cardiovascular disease. Whether weight reduction prior to pregnancy or restricting weight gain during pregnancy will reduce the risk of preeclampsia is not established. However, the general health benefits of weight loss in obese individuals justify weight loss before pregnancy. Similarly the Institute of Medicine recommended reduced weight gain for obese pregnant women.21 Whether these behavioral modifications will reduce the risk of preeclampsia will be established over time but is unlikely to be tested in randomized controlled trials.

The similarities between cardiovascular disease and preeclampsia justify considering mechanisms established as important contributors of obesity to cardiovascular disease as relevant targets for research to understand the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. It is unlikely that these factors act independently but rather are very likely interactive. Formally establishing the relationship of these mechanisms to preeclampsia should provide targets for future therapy.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by Grant NIH P01 HD030367

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Misra A, Khurana L. Obesity and the metabolic syndrome in developing countries. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2008;93:S9–30. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will all Americans become overweight or obese? estimating the progression and cost of the US obesity epidemic. Obesity. 2008;16:2323–30. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodnar LM, Ness RB, Markovic N, Roberts JM. The risk of preeclampsia rises with increasing prepregnancy body mass index. Annals of Epidemiology. 2005;15:475–82. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts JM, Gammill HS. Preeclampsia: recent insights. Hypertension. 2005;46:1243–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000188408.49896.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funai EF, Friedlander Y, Paltiel O, et al. Long-term mortality after preeclampsia. Epidemiology. 2005;16:206–15. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000152912.02042.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irgens HU, Reisaeter L, Irgens LM, Lie RT. Long term mortality of mothers and fathers after pre-eclampsia: population based cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2001;323:1213–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7323.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodnar LM, Catov JM, Klebanoff MA, Ness RB, Roberts JM. Prepregnancy body mass index and the occurrence of severe hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Epidemiology. 2007;18:234–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000254119.99660.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catov JM, Ness RB, Kip KE, Olsen J. Risk of early or severe pre-eclampsia related to pre-existing conditions. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;36:412–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl271. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahomed K, Williams MA, Woelk GB, et al. Risk Factors For Pre-Eclampsia Among Zimbabwean Women - Maternal Arm Circumference and Other Anthropometric Measures Of Obesity. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 1998;12:253–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1998.00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hossain P, Kawar B, El Nahas M. Obesity and diabetes in the developing world--a growing challenge. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356:213–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hauger MS, Gibbons L, Vik T, Belizan JM. Prepregnancy weight status and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2008;87:953–959. doi: 10.1080/00016340802303349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grundy MA, Woodcock S, Attwood SE. The surgical management of obesity in young women: consideration of the mother’s and baby’s health before, during, and after pregnancy. Surgical Endoscopy and Other Interventional Techniques. 2008;22:2107–2116. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abodeely A, Roye GD, Harrington DT, Cioffi WG. Pregnancy outcomes after bariatric surgery: maternal, fetal, and infant implications. Surgery for Obesity and Related Diseases. 2008;4:464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarthy EA, Strauss BJ, Walker SP, Permezel M. Determination of maternal body composition in pregnancy and its relevance to perinatal outcomes. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 2004;59:731–42. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000140039.10861.91. quiz 745-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lukaski HC, Siders WA, Nielsen EJ, Hall CB. Total body water in pregnancy: assessment by using bioelectrical impedance. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1994;59:578–85. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/59.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Raaij JM, Peek ME, Vermaat-Miedema SH, Schonk CM, Hautvast JG. New equations for estimating body fat mass in pregnancy from body density or total body water. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1988;48:24–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gustat J, Elkasabany A, Srinivasan S, Berenson GS. Relation of abdominal height to cardiovascular risk factors in young adults: the Bogalusa heart study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;151:885–91. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fain JN, Madan AK, Hiler ML, Cheema P, Bahouth SW. Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology. 2004;145:2273–82. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minocci A, Savia G, Lucantoni R, et al. Leptin plasma concentrations are dependent on body fat distribution in obese patients. International Journal of Obesity. 2000;24:1139–1144. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg AH, Scherer PE. Adipose tissue, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation Research. 2005;96:939–49. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163635.62927.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee to Reexamine IOM Pregnancy Weight Guidelines . Weight gain during pregnancy : reexamining the guidelines. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fortner RT, Pekow P, Solomon CG, Markenson G, Chasan-Taber L. Prepregnancy body mass index, gestational weight gain, and risk of hypertensive pregnancy among Latina women. American Journal Of Obstetrics And Gynecology. 2009;200 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briana DD, Malamitsi-Puchner A. Adipocytokines in Normal and Complicated Pregnancies. Reproductive Sciences. 2009;16:921–937. doi: 10.1177/1933719109336614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenberg AS, Obin MS. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;83:461S–465S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.2.461S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meigs JB, Wilson PW, Fox CS, et al. Body mass index, metabolic syndrome, and risk of type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006;91:2906–12. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaaja R. Insulin resistance syndrome in preeclampsia. Seminars in Reproductive Endocrinology. 1998;16:41–46. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1016251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laivuori H, Kaaja R, Koistinen H, et al. Leptin during and after preeclamptic or normal pregnancy: Its relation to serum insulin and insulin sensitivity. Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental. 2000;49:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(00)91559-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galili O, Versari D, Sattler KJ, et al. Early experimental obesity is associated with coronary endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. American Journal of Physiology - Heart & Circulatory Physiology. 2007;292:H904–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00628.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dandona P, Aljada A, Chaudhuri A, Mohanty P, Garg R. Metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive perspective based on interactions between obesity, diabetes, and inflammation. Circulation. 2005;111:1448–54. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158483.13093.9D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forest JC, Girouard J, Masse J, et al. Early occurrence of metabolic syndrome after hypertension in pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2005;105:1373–80. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000163252.02227.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vangaal LF, Zhang AG, Steijaert MM, Deleeuw IH. Human obesity: From lipid abnormalities to lipid oxidation. International Journal of Obesity. 1995;19:S21–S26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schinner S, Scherbaum WA, Bornstein SR, Barthel A. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance. Diabetic Medicine. 2005;22:674–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parthasarathy S, Rankin SM. Role of oxidized low density lipoprotein in atherogenesis. Progress in Lipid Research. 1992;31:127–143. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(92)90006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolf M, Kettyle E, Sandler L, Ecker JL, Roberts J, Thadhani R. Obesity and preeclampsia: the potential role of inflammation. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2001;98:757–62. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01551-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bodnar LM, Ness RB, Harger GF, Roberts JM. Inflammation and triglycerides partially mediate the effect of prepregnancy body mass index on the risk of preeclampsia. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2005;162:1198–206. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamaguchi M, Murakami T, Tomimatsu T, et al. Autocrine inhibition of leptin production by tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) through TNF-alpha type-I receptor in vitro. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 1998;244:30–4. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conrad KP, Benyo DF. Placental cytokines and the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 1997;37:240–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1997.tb00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kupferminc MJ, Peaceman AM, Wigton TR, Rehnberg KA, Socol ML. Tumor necrosis factor-a is elevated in plasma and amniotic fluid of patients with severe preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1994;170:1752–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benyo DF, Smarason A, Redman CW, Sims C, Conrad KP. Expression of inflammatory cytokines in placentas from women with preeclampsia. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2001;86:2505–12. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.6.7585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Founds SA, Powers RW, Patrick TE, et al. A comparison of circulating TNF-alpha in obese and lean women with and without preeclampsia. Hypertension in Pregnancy. 2008;27:39–48. doi: 10.1080/10641950701825838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart FM, Freeman DJ, Ramsay JE, Greer IA, Caslake M, Ferrell WR. Longitudinal assessment of maternal endothelial function and markers of inflammation and placental function throughout pregnancy in lean and obese mothers. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2007;92:969–75. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grimble RF. Inflammatory status and insulin resistance. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition & Metabolic Care. 2002;5:551–9. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200209000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Conrad KP, Miles TM, Benyo DF. Circulating levels of immunoreactive cytokines in women with preeclampsia. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 1998;40:102–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1998.tb00398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ukkola O, Bouchard C. Clustering of metabolic abnormalities in obese individuals: the role of genetic factors. Annals of Medicine. 2001;33:79–90. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neuhouser ML, Rock CL, Eldridge AL, et al. Serum concentrations of retinol, alpha-tocopherol and the carotenoids are influenced by diet, race and obesity in a sample of healthy adolescents. J Nutr. 2001;131:2184–91. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.8.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wallstrom P, Wirfalt E, Lahmann PH, Gullberg B, Janzon L, Berglund G. Serum concentrations of beta-carotene and alpha-tocopherol are associated with diet, smoking, and general and central adiposity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:777–85. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clausen T, Slott M, Solvoll K, Drevon CA, Vollset SE, Henriksen T. High intake of energy, sucrose, and polyunsaturated fatty acids is associated with increased risk of preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;185:451–458. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.116687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Matsuzawa Y. The metabolic syndrome and adipocytokines. FEBS Letters. 2006;580:2917–21. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barash IA, Cheung CC, Weigle DS, Ren H, Kabigting EB. Leptin is a metabolic signal to the reproductive system. Endocrinology. 1996;137:3144–47. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.7.8770941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beltowski J. Leptin and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Vleuten GM, Veerkamp MJ, van Tits LJ, et al. Elevated leptin levels in subjects with familial combined hyperlipidemia are associated with the increased risk for CVD. Atherosclerosis. 2005;183:355–60. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Henson MC, Castracane VD. Leptin in pregnancy. Biology of Reproduction. 2000;63:1219–1228. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.5.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Correia ML, Haynes WG. Leptin, obesity and cardiovascular disease. Current Opinion in Nephrology & Hypertension. 2004;13:215–23. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200403000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laivuori H, Gallaher MJ, Collura L, et al. Relationships between maternal plasma leptin, placental leptin mRNA and protein in normal pregnancy, pre-eclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction without pre-eclampsia. Molecular Human Reproduction. 2006;12:551–556. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jakimiuk AJ, Skalba P, Huterski D, Tarkowski R, Haczynski J, Magoffin DA. Leptin messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) content in the human placenta at term: relationship to levels of leptin in cord blood and placental weight. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2003;17:311–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mise H, Sagawa N, Matsumoto T, et al. Augmented placental production of leptin in preeclampsia: possible involvement of placental hypoxia. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1998;83:3225–3229. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.9.5117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mccarthy JF, Misra DN, Roberts JM. Maternal plasma leptin is increased in preeclampsia and positively correlates with fetal cord concentration. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1999;180:731–736. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martinez-Abundis E, Gonzalez-Ortiz M, Pascoe-Gonzalez S. Serum leptin levels and the severity of preeclampsia. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2000;264:71–73. doi: 10.1007/s004040000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Teppa RJ, Ness RB, Crombleholme WR, Roberts JM. Free leptin is increased in normal pregnancy and further increased in preeclampsia. Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental. 2000;49:1043–1048. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.7707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chappell LC, Seed PT, Briley A, et al. A longitudinal study of biochemical variables in women at risk of preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;187:127–36. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haugen F, Ranheim T, Harsem NK, Lips E, Staff AC, Drevon CA. Increased plasma levels of adipokines in preeclampsia: relationship to placenta and adipose tissue gene expression. American Journal Of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism. 2006;290:E326–E333. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00020.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kajantie E, Kaaja R, Ylikorkala O, Andersson S, Laivuori H. Adiponectin concentrations in maternal serum: elevated in preeclampsia but unrelated to insulin sensitivity. Journal of the Society for Gynecologic Investigation. 2005;12:433–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu D, Yang X, Wu Y, Wang H, Huang H, Dong M. Serum adiponectin, leptin and soluble leptin receptor in pre-eclampsia. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics. 2006;95:121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramsay JE, Jamieson N, Greer IA, Sattar N. Paradoxical elevation in adiponectin concentrations in women with preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2003;42:891–4. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000095981.92542.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, et al. Maternal serum adiponectin multimers in preeclampsia. Journal of Perinatal Medicine. 2009;37:349–63. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fasshauer M, Waldeyer T, Seeger J, et al. Serum levels of the adipokine visfatin are increased in pre-eclampsia. Clinical Endocrinology. 2008;69:69–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takemura Y, Osuga Y, Koga K, et al. Selective increase in high molecular weight adiponectin concentration in serum of women with preeclampsia. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2007;73:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levine RJ, Qian C, Maynard SE, Yu KF, Epstein FH, Karumanchi SA. Serum sFlt1 concentration during preeclampsia and mid trimester blood pressure in healthy nulliparous women. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;194:1034–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maynard SE, Min JY, Merchan J, et al. Excess placental soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt1) may contribute to endothelial dysfunction, hypertension, and proteinuria in preeclampsia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;111:649–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI17189. [comment] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miyazawa-Hoshimoto S, Takahashi K, Bujo H, Hashimoto N, Saito Y. Elevated serum vascular endothelial growth factor is associated with visceral fat accumulation in human obese subjects. Diabetologia. 2003;46:1483–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Powers RW, Roberts JM, Plymire DA, et al. High prepregnancy body mass index is associated with low PlGF in preeclampsia and uncomplicated pregnancies. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010 (Abtract SGI 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 72.Albert NM. We are what we eat: women and diet for cardiovascular health. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2005;20:451–60. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200511000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roberts JM, Balk JL, Bodnar LM, Belizan JM, Bergel E, Martinez A. Nutrient Involvement in Preeclampsia. Journal of Nutrition. 2003;133:1684S–1692S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1684S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang C, Williams MA, King IB, et al. Vitamin C and the risk of preeclampsia--results from dietary questionnaire and plasma assay. Epidemiology. 2002;13:409–16. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Poston L, Briley AL, Seed PT, Kelly FJ, Shennan AH, Vitamins in Pre-eclampsia Trial C Vitamin C and vitamin E in pregnant women at risk for pre-eclampsia (VIP trial): randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;367:1145–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68433-X. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chappell LC, Seed PT, Briley AL, et al. Effect of antioxidants on the occurrence of pre-eclampsia in women at increased risk: a randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;354:810–816. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rumbold AR, Crowther CA, Haslam RR, Dekker GA, Robinson JS, Group AS. Vitamins C and E and the risks of preeclampsia and perinatal complications. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354:1796–806. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054186. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Holven KB, Holm T, Aukrust P, et al. Effect of folic acid treatment on endothelium-dependent vasodilation and nitric oxide-derived end products in hyperhomocysteinemic subjects. American Journal of Medicine. 2001;110:536–42. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00696-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Doshi SN, Mcdowell IF, Moat SJ, et al. Folic acid improves endothelial function in coronary artery disease via mechanisms largely independent of homocysteine lowering. Circulation. 2002;105:22–6. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Title LM, Cummings PM, Giddens K, Genest JJ, Nassar BA. Effect of folic acid and antioxidant vitamins on endothelial dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000;36:758–765. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00809-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.van Etten RW, de KEJ, Verhaar MC, Gaillard CA, Rabelink TJ. Impaired NO-dependent vasodilation in patients with Type II (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus is restored by acute administration of folate. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1004–10. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0862-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stroes ES, van Faassen EE, Yo M, et al. Folic acid reverts dysfunction of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circ Res. 2000;86:1129–34. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.11.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wilmink HW, Stroes ES, Erkelens WD, et al. Influence of folic acid on postprandial endothelial dysfunction. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis & Vascular Biology. 2000;20:185–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.1.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Williams MA, Zingheim RW, King IB, Zebelman AM. Omega-3 fatty acids in maternal erythrocytes and risk of preeclampsia. Epidemiology. 1995;6:232–7. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199505000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Williams MA, King IB, Sorensen TK, et al. Risk of preeclampsia in relation to elaidic acid (trans fatty acid) in maternal erythrocytes. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1998;46:84–7. doi: 10.1159/000010007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Clausen T, Djurovic S, Henriksen T. Dyslipidemia in early second trimester is mainly a feature of women with early onset pre-eclampsia. BJOG. 2001;108:1081–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kesmodel U, Olsen SF, Salvig JD. Marine n-3 fatty acid and calcium intake in relation to pregnancy induced hypertension, intrauterine growth retardation, and preterm delivery. A case-control study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1997;76:38–44. doi: 10.3109/00016349709047782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Popeski D, Ebbeling LR, Brown PB, Hornstra G, Gerrard JM. Blood pressure during pregnancy in Canadian Inuit: community differences related to diet. C.M.A.J. 1991;145:445–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2004;79:537–43. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.537. [see comment][erratum appears in Am J Clin Nutr. 2004 Oct;80(4):1090] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Elliott SS, Keim NL, Stern JS, Teff K, Havel PJ. Fructose, weight gain, and the insulin resistance syndrome. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;76:911–22. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.5.911. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nakagawa T, Hu H, Zharikov S, et al. A causal role for uric acid in fructose-induced metabolic syndrome. American Journal of Physiology - Renal Physiology. 2006;290:F625–31. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00140.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mcnamara DJ, Howell WH. Epidemiologic data linking diet to hyperlipidemia and Arteriosclerosis And Thrombosis. Seminars in Liver Disease. 1992;12:347–55. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040404. [Review] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Canoy D, Wareham N, Welch A, et al. Plasma ascorbic acid concentrations and fat distribution in 19,068 British men and women in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Norfolk cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1203–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Andersen LF, Jacobs DR, Jr, Gross MD, Schreiner PJ, Williams O Dale, Lee DH. Longitudinal associations between body mass index and serum carotenoids: the CARDIA study. Br J Nutr. 2006;95:358–65. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Saftlas AF, Logsden-Sackett N, Wang W, Woolson R, Bracken MB. Work, leisure-time physical activity, and risk of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:758–65. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Marcoux S, Brisson J, Fabia J. The effect of leisure time physical activity on the risk of pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 1989;43:147–52. doi: 10.1136/jech.43.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dempsey JC, Sorensen TK, Qiu CF, Luthy DA, Williams MA. History of abortion and subsequent risk of preeclampsia. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2003;48:509–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sorensen TK, Williams MA, Lee IM, Dashow EE, Thompson ML, Luthy DA. Recreational physical activity during pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2003;41:1273–80. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000072270.82815.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Budhiraja R, Quan SF. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular health. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2005;11:501–6. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000183058.52924.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ayas NT, White DP, Manson JE, et al. A prospective study of sleep duration and coronary heart disease in women. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2003;163:205–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.2.205. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.White DP. Pathogenesis of obstructive and central sleep apnea. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 2005;172:1363–70. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1631SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ip MSM, Lam KSL, Ho CM, Tsang KWT, Lam WK. Serum leptin and vascular risk factors in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2000;118:580–586. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Pack AI. Advances in sleep-disordered breathing. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 2006;173:7–15. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200509-1478OE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. HIF-1-dependent respiratory, cardiovascular, and redox responses to chronic intermittent hypoxia. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2007;9:1391–6. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Robinson GV, Pepperell JC, Segal HC, Davies RJ, Stradling JR. Circulating cardiovascular risk factors in obstructive sleep apnoea: data from randomised controlled trials. Thorax. 2004;59:777–82. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.018739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Punjabi NM, Polotsky VY. Disorders of glucose metabolism in sleep apnea. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;99:1998–2007. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00695.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.VanHelder T, Symons JD, Radomski MW. Effects of sleep deprivation and exercise on glucose tolerance. Aviation Space & Environmental Medicine. 1993;64:487–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Punjabi NM, Shahar E, Redline S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance: the Sleep Heart Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;160:521–30. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Young T, Peppard PE, Taheri S. Excess weight and sleep-disordered breathing. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;99:1592–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00587.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Namyslowski G, Scierski W, Mrowka-Kata K, Kawecka I, Kawecki D, Czecior E. Sleep Study in Patients with Overweight and Obesity. Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 2005:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Schafer H, Pauleit D, Sudhop T, Gouni-Berthold I, Ewig S, Berthold HK. Body fat distribution, serum leptin, and cardiovascular risk factors in men with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2002;122:829–39. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.3.829. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Marik PE. Leptin, obesity, and obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2000;118:569–571. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lu BS, Zee PC. Sleep Loss and the Risk for Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Medscape Current Perspectives in Insomnia. 2006;8 [Google Scholar]

- 114.Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP. Sleep apnea is a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2005;9:211–24. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Santiago JR, Nolledo MS, Kinzler W, Santiago TV. Sleep and sleep disorders in pregnancy. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;134:396–408. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-5-200103060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sahota PK, Jain SS, Dhand R. Sleep disorders in pregnancy. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2003;9:477–83. doi: 10.1097/00063198-200311000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Izci B, Martin SE, Dundas KC, Liston WA, Calder AA, Douglas NJ. Sleep complaints: snoring and daytime sleepiness in pregnant and pre-eclamptic women. Sleep Medicine. 2005;6:163–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Izci B, Riha RL, Martin SE, et al. The upper airway in pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 2003;167:137–40. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-590OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Connolly G, Razak AR, Hayanga A, Russell A, Mckenna P, Mcnicholas WT. Inspiratory flow limitation during sleep in pre-eclampsia: comparison with normal pregnant and nonpregnant women. European Respiratory Journal. 2001;18:672–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.01.00053501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Franklin KA, Holmgren PA, Jonsson F, Poromaa N, Stenlund H, Svanborg E. Snoring, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and growth retardation of the fetus. Chest. 2000;117:137–41. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Leiper J, Vallance P. Biological significance of endogenous methylarginines that inhibit nitric oxide synthases. Cardiovascular Research. 1999;43:542–8. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Feng Q, Lu X, Fortin AJ, et al. Elevation of an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis in experimental congestive heart failure. Cardiovascular Research. 1998;37:667–75. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Chan NN, Chan JC. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA): a potential link between endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular diseases in insulin resistance syndrome? Diabetologia. 2002;45:1609–16. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0975-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gokce N. L-arginine and hypertension. Journal of Nutrition. 2004;134:2807S–2811S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.10.2807S. discussion 2818S-2819S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Maas R, Boger RH. Old and new cardiovascular risk factors: from unresolved issues to new opportunities. Atherosclerosis Supplements. 2003;4:5–17. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5688(03)00028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Krzyzanowska K, Mittermayer F, Kopp HP, Wolzt M, Schernthaner G. Weight loss reduces circulating asymmetrical dimethylarginine concentrations in morbidly obese women. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2004;89:6277–81. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Boger RH, Bode-Boger SM, Sydow K, Heistad DD, Lentz SR. Plasma concentration of asymmetric dimethylarginine, an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, is elevated in monkeys with hyperhomocyst(e)inemia or hypercholesterolemia. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis & Vascular Biology. 2000;20:1557–64. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.6.1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Paiva H, Lehtimaki T, Laakso J, et al. Dietary composition as a determinant of plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine in subjects with mild hypercholesterolemia. Metabolism: Clinical & Experimental. 2004;53:1072–5. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2003.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Nash DT. Insulin resistance, ADMA levels, and cardiovascular disease. Jama. 2002;287:1451–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Stuhlinger MC, Abbasi F, Chu JW, et al. Relationship between insulin resistance and an endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. Jama. 2002;287:1420–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.11.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Yoo JH, Lee SC. Elevated levels of plasma homocyst(e)ine and asymmetric dimethylarginine in elderly patients with stroke. Atherosclerosis. 2001;158:425–30. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00444-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ohike Y, Kozaki K, Iijima K, et al. Amelioration of vascular endothelial dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome by nasal continuous positive airway pressure--possible involvement of nitric oxide and asymmetric NG, NG-dimethylarginine. Circulation Journal. 2005;69:221–6. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Eid HM, Arnesen H, Hjerkinn EM, Lyberg T, Seljeflot I. Relationship between obesity, smoking, and the endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, asymmetric dimethylarginine. Metabolism: Clinical & Experimental. 2004;53:1574–9. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mclaughlin T, Stuhlinger M, Lamendola C, et al. Plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine concentrations are elevated in obese insulin-resistant women and fall with weight loss. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2006;91:1896–900. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Marliss EB, Chevalier S, Gougeon R, et al. Elevations of plasma methylarginines in obesity and ageing are related to insulin sensitivity and rates of protein turnover. Diabetologia. 2006;49:351–9. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Achan V, Broadhead M, Malaki M, et al. Asymmetric dimethylarginine causes hypertension and cardiac dysfunction in humans and is actively metabolized by dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis & Vascular Biology. 2003;23:1455–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000081742.92006.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Boger RH. The emerging role of asymmetric dimethylarginine as a novel cardiovascular risk factor. Cardiovascular Research. 2003;59:824–33. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00500-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Boger RH, Bode-Boger SM. Asymmetric dimethylarginine, derangements of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase pathway, and cardiovascular diseases. Seminars in Thrombosis & Hemostasis. 2000;26:539–45. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-13210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Boger RH, Sydow K, Borlak J, et al. LDL cholesterol upregulates synthesis of asymmetrical dimethylarginine in human endothelial cells: involvement of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases. Circulation Research. 2000;87:99–105. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ito A, Tsao PS, Adimoolam S, Kimoto M, Ogawa T, Cooke JP. Novel mechanism for endothelial dysfunction: dysregulation of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circulation. 1999;99:3092–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Leiper J, Murray-Rust J, Mcdonald N, Vallance P. S-nitrosylation of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase regulates enzyme activity: further interactions between nitric oxide synthase and dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99:13527–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212269799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Lin KY, Ito A, Asagami T, et al. Impaired nitric oxide synthase pathway in diabetes mellitus: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine and dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circulation. 2002;106:987–92. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000027109.14149.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Stuhlinger MC, Tsao PS, Her JH, Kimoto M, Balint RF, Cooke JP. Homocysteine impairs the nitric oxide synthase pathway: role of asymmetric dimethylarginine. Circulation. 2001;104:2569–75. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.098514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Millatt LJ, Whitley GS, Li D, et al. Evidence for dysregulation of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase I in chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Circulation. 2003;108:1493–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000089087.25930.FF. [see comment] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Cooke JP. Asymmetrical dimethylarginine: the Uber marker? Circulation. 2004;109:1813–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000126823.07732.D5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Tran CT, Leiper JM, Vallance P. The DDAH/ADMA/NOS pathway. Atherosclerosis Supplements. 2003;4:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5688(03)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Nijveldt RJ, Teerlink T, Siroen MP, van LAA, Rauwerda JA, van LPA. The liver is an important organ in the metabolism of asymmetrical dimethylarginine (ADMA) Clinical Nutrition. 2003;22:17–22. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2002.0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Osanai T, Saitoh M, Sasaki S, Tomita H, Matsunaga T, Okumura K. Effect of shear stress on asymmetric dimethylarginine release from vascular endothelial cells. Hypertension. 2003;42:985–90. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000097805.05108.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Sydow K, Munzel T. ADMA and oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis Supplements. 2003;4:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5688(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Ueda S, Kato S, Matsuoka H, et al. Regulation of cytokine-induced nitric oxide synthesis by asymmetric dimethylarginine: role of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. Circulation Research. 2003;92:226–33. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000052990.68216.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Takiuchi S, Fujii H, Kamide K, et al. Plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine and coronary and peripheral endothelial dysfunction in hypertensive patients. American Journal of Hypertension. 2004;17:802–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Tarnow L, Hovind P, Teerlink T, Stehouwer CD, Parving HH. Elevated plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine as a marker of cardiovascular morbidity in early diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:765–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Stuhlinger MC, Stanger O. Asymmetric dimethyl-L-arginine (ADMA): a possible link between homocyst(e)ine and endothelial dysfunction. Current Drug Metabolism. 2005;6:3–14. doi: 10.2174/1389200052997393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Aicher A, Heeschen C, Dimmeler S. The role of NOS3 in stem cell mobilization. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2004;10:421–5. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Aicher A, Heeschen C, Mildner-Rihm C, et al. Essential role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase for mobilization of stem and progenitor cells. Nature Medicine. 2003;9:1370–6. doi: 10.1038/nm948. [erratum appears in Nat Med. 2004 Sep;10(9):999] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Pettersson A, Hedner T, Milsom I. Increased Circulating Concentrations Of Asymmetric Dimethyl Arginine (Adma), an Endogenous Inhibitor Of Nitric Oxide Synthesis, In Preeclampsia. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1998;77:808–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Savvidou MD, Hingorani AD, Tsikas D, Frolich JC, Vallance P, Nicolaides KH. Endothelial dysfunction and raised plasma concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine in pregnant women who subsequently develop pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2003;361:1511–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13177-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]