Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is primarily defined and staged according to the magnitude of rise in serum creatinine. We sought to determine if another dimension of AKI, duration, adds additional prognostic information above magnitude alone. We prospectively studied 35,302 diabetic patients from 123 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers undergoing their first non-cardiac surgery between 2000 and 2004. The main outcome was long-term mortality in those that survived the index hospitalization. The exposure, AKI, was stratified by magnitude according to the AKI Network (AKIN) stages (stages 1, 2 and 3), and by duration (short [≤2 days], medium [3-6 days], long [≥ 7 days]). Overall, 17.8% of the patients experienced at least stage 1 AKI or greater after surgery. Both the magnitude and duration of AKI were associated with long-term survival in a dose-dependent manner (p < 0.001 for both). Within each AKIN stage, longer duration of AKI was associated with a graded higher rate of mortality (p < 0.001 for each stratum). However, within each of the categories of AKI duration, the AKIN stage was not associated was mortality. When considered separately in multivariate analyses, both a higher AKIN stage and duration were independently associated with increased risk of long-term mortality. In conclusion, duration of AKI adds additional information to predict long-term mortality in patients with AKI.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is common and complex disorder, and frequently occurs in hospitalized patients.1 Although AKI has been conceptualized by abrupt elevations in serum creatinine, for decades there has been a lack of a consensus definition. Recently the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) and the Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) developed new classification systems for AKI. The ADQI proposed the Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss of Kidney Function, and End Stage Kidney Disease (RIFLE classification)2 and subsequently the AKIN group made a slight modification to the RIFLE classification system.3 Implicit in both these classification systems is a dose-response relationship between severity of AKI stage and outcome.4-9 The RIFLE and AKIN definitions of AKI primarily involve a magnitude component and take into account the degree of elevation of serum creatinine. The AKIN and RIFLE systems do not take into account the etiology, the duration of serum creatinine elevation, or recovery into its assessment of AKI.

In clinical practice, many data elements, in addition to the absolute elevation in serum creatinine, are considered in assessing the severity and prognosis after AKI. An important parameter that is often accounted for by clinicians is the duration of AKI. Fundamentally, the duration of AKI, along with examination of the urine sediment,10 helps differentiate between “prerenal AKI” and “intrinsic AKI” or acute tubular necrosis. In fact, it can be argued that the duration of the elevation of serum creatinine is the most important factor when trying to differentiate between prerenal and intrinsic AKI. Significant azotemia can be witnessed in the setting of severe prerenal dysfunction, and the urinary sediment is not always completely accurate for distinguishing between these two entities.10 However, brisk recovery, thereby a short duration of AKI, suggests that the elevation of serum creatinine was probably not due to intrinsic AKI. Intrinsic AKI involves tubular cell injury and the process of repair, which involves dedifferentiation and redifferentiation, and takes more than 24-48 hours.11, 12

The objective of this project was to explore the association between duration of AKI and long-term mortality and to examine if duration of AKI offered any additional prognostic information over the magnitude of elevation in serum creatinine. We chose to investigate these relationships in a population of post-operative AKI, as the timing of the insult is known. Thus the duration of AKI is less confounded by repeated clinical or sub-clinical insults that could occur in a typical hospitalized or critically ill population.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Among the 35,302 Veterans that underwent non-cardiac surgery between 2000 and 2004 and met our inclusion criteria, the median length of hospital admission was 6 days (range 0 to 314 days). Patients surviving hospitalization for non-cardiac surgery were divided into three categories of AKI by AKIN stage (magnitude) and three categories of duration of AKI. 6257 (17.8%) patients had some degree of AKI by AKIN criteria (stage 1: 14.5%, stage 2: 2.2%, stage 3: 1.1%). 4205 (11.9%) experienced short duration of AKI (1-2 days), 1379 (3.9%) experienced medium duration (3-6 days), and 673 (1.9%) experienced long duration (≥ 7 days) of AKI. Baseline characteristics by strata of AKIN and AKI duration are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Baseline Characteristics and the AKIN Staging System and AKI Duration

| No AKI | Acute Kidney Injury | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKIN Stage | AKI Duration | ||||||||

| Stage 1 | Stage 2 | Stage 3 | P-value | Short | Medium | Long | P-value | ||

| Overall | 29045 (82.3) | 5109 (14.5) | 760 (2.2) | 388 (1.1) | 4205 (11.9) | 1379 (3.9) | 673 (1.9) | ||

| Demographics | |||||||||

| Age (years) | 66 ± 10 | 67 ± 10 | 66 ± 10 | 66 ± 11 | <0.001 | 67 ± 10 | 68 ± 10 | 68 ± 10 | <0.001 |

| Male | 97 | 98 | 98 | 96 | 0.08 | 98 | 99 | 98 | <0.001 |

| White | 67 | 65 | 65 | 63 | 0.005 | 64 | 67 | 67 | 0.12 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| COPD | 15 | 18 | 18 | 22 | <0.001 | 17 | 20 | 23 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 41 | 50 | 46 | 50 | <0.001 | 47 | 53 | 55 | <0.001 |

| Ventilator dependent | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 6.4 | <0.001 |

| Smoker | 28 | 26 | 25 | 34 | 0.08 | 26 | 24 | 29 | 0.008 |

| Pre-operative Infection | 22 | 25 | 24 | 34 | <0.001 | 23 | 30 | 34 | <0.001 |

| Functional dependency | 17 | 21 | 22 | 23 | <0.001 | 19 | 24 | 27 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol Use > 2 drinks/day | 6 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 0.56 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 0.59 |

| Weight loss > 10% last 6 months | 4 | 5 | 8 | 7 | <0.001 | 5 | 7 | 10 | <0.001 |

| Surgery Characteristics | |||||||||

| OR time (minutes) | 143 ± 102 | 166 ± 122 | 174 ± 120 | 176 ± 134 | <0.001 | 163 ±119 | 167 ± 120 | 197 ± 146 | <0.001 |

| General anesthesia | 79 | 82 | 86 | 89 | <0.001 | 82 | 84 | 90 | <0.001 |

| ASA Class 4/5 | 17 | 25 | 25 | 33 | <0.001 | 21 | 30 | 42 | <0.001 |

| Emergency case | 10 | 12 | 13 | 20 | <0.001 | 11 | 15 | 21 | <0.001 |

| Specialty of Surgeon | N/A | N/A | |||||||

| General surgery | 32 | 34 | 38 | 36 | 34 | 36 | 37 | ||

| Neurosurgery | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Orthopedic surgery | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 20 | 15 | 12 | ||

| Thoracic surgery | 4 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Urologic surgery | 12 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 12 | 12 | 7 | ||

| Vascular surgery | 24 | 21 | 17 | 26 | 20 | 22 | 29 | ||

| Other | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Pre-operative Laboratory Values | |||||||||

| Hematocrit (%) | 38 ± 6 | 36 ± 6 | 36 ± 6 | 35 ± 6 | <0.001 | 37 ± 6 | 35 ± 6 | 34 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| White blood cells (1000/μL/mm3) | 8.9 ± 4.4 | 9.1 ± 5.4 | 9.0 ± 5.0 | 10.0 ± 5.2 | <0.001 | 9.0 ± 5.6 | 9.4 ± 4.7 | 9.9 ± 5.1 | <0.001 |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 3.3 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | <0.001 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | <0.001 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.5 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| CKD Stage | <0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||

| Stage 1-2 | 73 | 58 | 74 | 65 | 65 | 52 | 47 | ||

| Stage 3 | 25 | 36 | 24 | 24 | 31 | 39 | 39 | ||

| Stage 4 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 14 | ||

| HbA1C (%) | 8.0 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 2.2 | 0.78 | 7.9 ± 2.0 | 7.9 ± 2.0 | 7.8 ± 2.0 | 0.25 |

| Mean glucose, 24 hours post-op (mg/dl) | 184 ± 61 | 196 ± 68 | 199 ± 70 | 189 ± 67 | <0.001 | 197 ± 70 | 194 ± 65 | 191 ± 64 | <0.001 |

| Median Survival (years) | 3.8 | 3.3 | 3.0 | 2.4 | <0.001 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 2.1 | <0.001 |

Values are percentages for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviations for continuous variables

P-values represent results from Mantel-Hantzel chi-square test for trend for categorical variables and represent results from analysis of variance for continuous variables

N/A- p-values not calculated for type of surgery

Other abbreviations: AKI- acute kidney injury; ASA- American Society of Anesthesiologists; COPD – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HbA1C- hemoglobin A1C. CKD: Chronic Kidney Disease (Stages 1-2 GFR ≥ 60 ml/min/1.73 m2; Stage 3 GFR 30-59 ml/min/1.73 m2; Stage 4 GFR 16-29 ml/min/1.73 m2).

Long-Term Survival

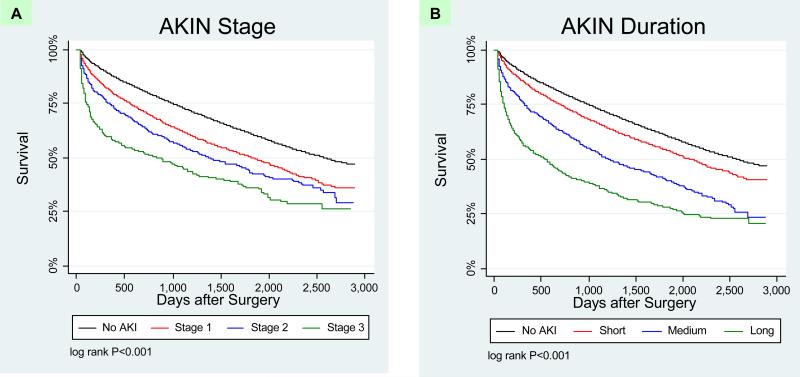

Among the 35,302 survivors of hospitalization, 14,582 deaths occurred during 123,118 patient-years of follow-up (mortality rate 11.8 per 100 person-years). Overall, the median length of follow-up for the entire cohort was 3.8 years (mean 3.7 years, range 0 to 7.9 years). The median length of survival decreased with both magnitude and duration of AKI (Table 1). Long-term survival was significantly different by both AKIN stage (Figure 1a; log rank test P < 0.001) and by duration of AKI (Figure 1b; log rank test P < 0.001).

Figure 1. Kaplan Meier Survival Plots of AKI by Magnitude and Duration.

Panel A. Survival among patients by AKIN stages of AKI versus no AKI. Increasing AKIN stage is associated with worse survival.

Panel B. Survival among patients by duration of AKI versus no AKI. Increasing duration of AKI is associated with worse survival.

Adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for each AKI category as defined in separate models by magnitude and duration are summarized in Table 3. Both AKIN stage and AKI duration were independently associated with long-term mortality. However, because of significant co linearity between magnitude and duration of AKI (r = 0.87), we were not able to include both variables in the same Cox Proportional Hazards model. The relationship between duration of AKI and long-term survival was not modified by pre-existing CKD (p = 0.92 for interaction).

Table 3.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Mortality after Hospitalization by AKI Definitions

| HR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AKIN | Upper | Lower | |

| Stage 1 | 1.24 | 1.17 | 1.31 |

| Stage 2 | 1.64 | 1.43 | 1.88 |

| Stage 3 | 1.96 | 1.63 | 2.37 |

| Duration | |||

| Short | 1.15 | 1.07 | 1.23 |

| Medium | 1.50 | 1.36 | 1.66 |

| Long | 2.01 | 1.77 | 2.28 |

Variables in final model for AKIN stage of AKI include the following: age, sex, race, chronic insulin use, mean 24 hour post-op glucose (categorical), operative time, ASA class 4/5, emergency surgery, baseline GFR, pre-operative infection, functional dependency, smoking status, weight loss > 10% last 6 months, chronic alcohol intake, COPD, pre-operative albumin, hematocrit, white blood cell count, and hemoglobin A1C.

Variables in final model for AKI duration include the same variables.

Referent group are those without AKI.

Abbreviations: AKIN- Acute Kidney Injury Network; HR- hazard ratio; CI- confidence interval

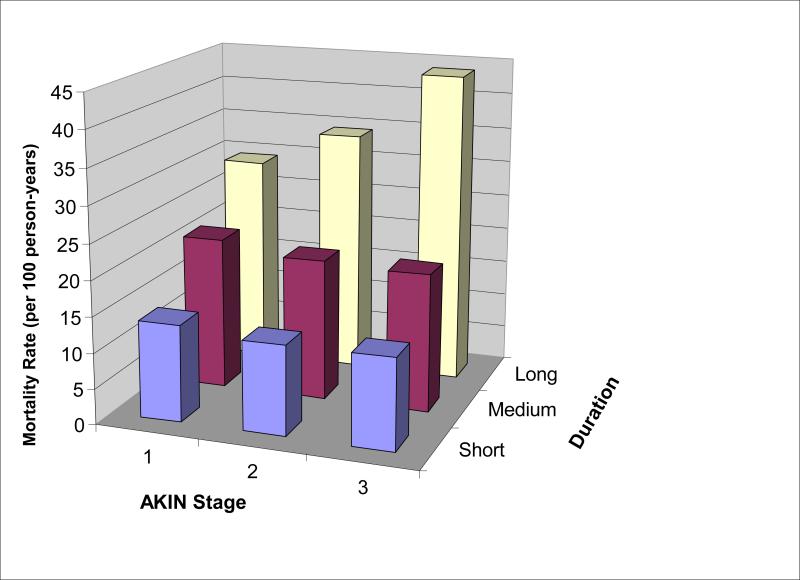

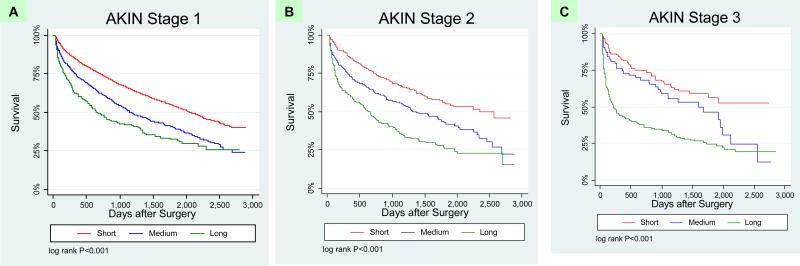

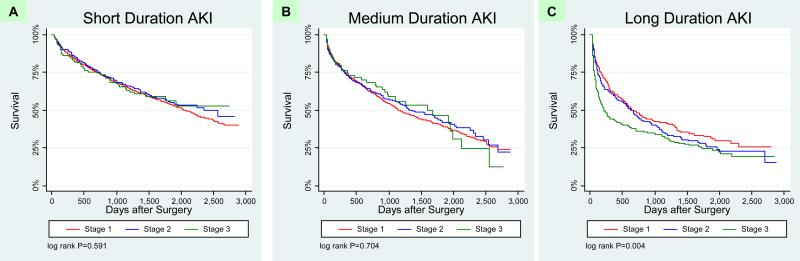

In order to better understand the prognostic role of duration of AKI, we examined subgroups of AKI, first by each stage of AKIN stratified by duration, and then AKI duration stratified by AKIN. We plotted magnitude and duration of AKI on a two-way graph with mortality rates (Figure 2). As the duration of AKI increased within each strata of AKI severity as defined by the AKIN criteria (magnitude), survival after hospitalization decreased. However, survival did not significantly change within each strata of AKI as classified by duration (Figure 2, Table 4). Notably, the mortality rates were greater for those with the lowest AKIN stage and medium or long duration of AKI (21.5 and 29.3 deaths/100 person-years, respectively) than for those with the most severe AKIN stage but short duration of AKI (12.8 deaths/100 person-years). These relationships were confirmed when we examined the stratified survival plots. Patients with increasing duration of AKI had significantly worse survival in every stage of AKIN (log rank test P < 0.001 for all 3 strata; Figure 3). In contrast, when patients were stratified by the duration of AKI, the magnitude of creatinine rise as classified by the AKIN was not significantly associated with survival in those with short and medium length of AKI (P values for log-rank test > 0.05; Figure 4). When patients who required acute renal replacement (n=132) post-operatively were examined separately from the rest of the cohort, they had the highest risk for death (adjusted HR 2.65, 95% CI 2.0-3.52).

Figure 2. Mortality Rates by Magnitude and Duration of AKI.

No increase in mortality rate is seen by AKIN Stage within AKI as stratified by duration. However, the mortality rate increased by duration within AKI as stratified by AKIN stage. The mortality rate for those with AKIN Stage 1 and long duration of AKI is more than 2-fold higher than for those with AKIN Stage 3 and short duration of AKI.

Table 4.

Incidence Rate of Death by AKI Magnitude and Duration

| Group | N of Subjects | Person-years Follow-up | N of deaths | Mortality Rate (Deaths/100 Person-Years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients | 35,302 | 123118 | 14582 | 11.8 | |

| No AKI | 29,067 | 103753 | 11382 | 11.0 | |

| AKIN Stage 1 | Short | 3642 | 12748 | 1744 | 13.7 |

| Medium | 1021 | 2975 | 641 | 21.5 | |

| Long | 241 | 569 | 167 | 29.3 | |

| AKIN Stage 2 | Short | 284 | 1001 | 126 | 12.6 |

| Medium | 260 | 758 | 151 | 19.9 | |

| Long | 188 | 422 | 145 | 34.3 | |

| AKIN Stage 3 | Short | 97 | 328 | 42 | 12.8 |

| Medium | 63 | 185 | 36 | 19.5 | |

| Long | 217 | 386 | 169 | 43.8 | |

AKI- acute kidney injury

AKIN- acute kidney injury network

Figure 3. Kaplan Meier Survival Plots: AKIN Stages Stratified by Duration.

Survival among patients by short, medium and long duration of AKI within AKIN stages 1, 2 and 3 (panels A, B, and C, respectively). Patients with increasing duration of AKI had significantly worse survival in every stage of AKIN.

Figure 4. Kaplan Meier Survival Plots: AKI Duration stratified by AKIN Stages.

Survival among patients by AKIN stages 1, 2 and 3 within short, medium, and long duration of AKI (panels A, B, and C, respectively). Once stratified by duration of AKI, there is minimal additional prognostic information offered by magnitude of creatinine rise.

Supplementary Analyses: AKI Recovery and Long-term Survival

We examined the relationship between duration of AKI, recovery of AKI, and survival in those with AKI that had ≥ 7 post-operative serum creatinine values. A total of 3207 patients that experienced AKI had ≥ 7 serum creatinine values, of which 1570 (50%) had short, 984 (31%) had medium, and 653 (20%) had long duration of AKI. Among these patients, 2269 (71%) recovered back to within 0.2 mg/dL of baseline by the time of discharge. Duration of AKI was associated with recovery (proportion of those with short, medium, long AKI that recovered: 88%, 72%, 28%, respectively, p< 0.001). Long-term survival was significantly better in those who recovered vs. those that did not (median survival 1088 days vs. 897 days, respectively; log-rank test p < 0.001). When stratified by recovery status and three lengths of duration, the duration of AKI was still significantly associated with long-term survival within both those that had non-recovery and those that recovered (log-rank test p = 0.006 and p < 0.001, respectively).

DISCUSSION

In this large, multicenter US Veterans Affairs-based surgical database, we demonstrated that the duration of AKI is independently associated with long-term mortality. This is the largest study to date that demonstrates the prognostic importance of duration of AKI. Furthermore, when we controlled for magnitude of rise in serum creatinine, the duration of AKI within each strata of AKIN stage was associated with long-term survival in a clear dose-dependent manner. In contrast, the AKIN stages of AKI provided little additional prognostic information once duration of AKI was controlled for. Most impressive was the fact that mortality rate for those with severe AKI (stage 3 AKIN) and short duration was approximately 50% lower than for those with the most mild stage of AKI (stage 1 AKIN) and medium or long duration of AKI. These findings, while potentially intuitive, are novel in the AKI literature and demonstrate the limitations of the current AKI classification systems. Only a few smaller studies have stratified survival by whether AKI recovered by the time of hospital discharge13, 14 or within 3 days of AKI, 15 however, these analyses were not as detailed as ours, nor were the interactions between various degrees of AKI magnitude and duration and recovery examined as thoroughly as in this current study. Herein, we demonstrated that duration of AKI still provided prognostic information even in the patients with AKI that recovered kidney function back to baseline by the time of hospital discharge.

Most, if not all previous publications on the long-term prognosis after AKI have focused solely on characterizing severity of AKI by the magnitude in rise of serum creatinine. Thus, it is highly likely that there was imperfect characterization of risk associated with AKI in all previous studies solely using the existing magnitude-based criteria for AKI. Our findings have important implications for the field of AKI. The current consensus definition for AKI as proposed by the AKIN group does not incorporate any duration component into the definition. However, given the fact that we found that the granularity of the risk associated with AKI in regards to long-term mortality is increased by examining not only the magnitude of rise in serum creatinine but also the duration of the rise, future studies should utilize at least this two dimensional approach (magnitude and duration) to analyze outcomes of AKI. The addition of another dimension to classification of AKI should be sought after and embraced. It is clear from clinical practice and from our data that a patient who experiences a large (e.g., 3 fold) but brief rise in serum creatinine is phenotypically very different from a patient who experiences a sustained rise of 50%. The current classification systems inappropriately assign higher risk to the first patient because the change in creatinine was numerically greater.

Classification of AKI by duration may be serving to discriminate between patients with “pre-renal” or hemodynamic AKI that does not result in any true injury to the renal tubular cells and those with true intrinsic renal injury (i.e., “acute tubular necrosis”). In addition, the duration of AKI may be a surrogate of recovery potential of the injured kidney. Some patients may be able to regain proper functioning of renal tubular cells more quickly due to younger age,16-18 more renal mass, or faster restoration of renal medullary blood flow. In addition, the duration of AKI may be reflective of overall severity of illness of the patient, as those who are more severely ill and have continued extra-renal organ dysfunction will take longer to recover. In contrast, the magnitude of serum creatinine rise depends on muscle mass, volume status and may not always be reflective of true tubular injury or the extent of injury. First, there is no doubt patients with prerenal AKI may achieve a serum creatinine concentration as high or even higher in some cases than patients with acute tubular necrosis, particularly in patients on agents that impair renal autoregulation (e.g., NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors).19-21 Second, the ability to generate higher serum creatinine is not only dependent upon a reduction in glomerular filtration rate, but also dependent on production of creatinine from skeletal muscle. Thus, in response to an insult of equal magnitude, a more robust and muscular patient will achieve a greater rise in serum creatinine than a frail, chronically ill patient. The robust and muscular patient will be more likely to survive long-term than the frail patient.

Our study does have some limitations. First, the results may lack generalizability. The population in this study was comprised solely of diabetic veterans who underwent non-cardiac surgery, and the preponderance of patients were male. Whether the same findings apply to non-diabetics in all clinical settings and females is unknown. Second, we did not have data on urine output, which is a component of the AKIN definition. It is possible that the results may have differed if urine output was incorporated into the AKIN definition of AKI applied to this cohort of patients. However, a recent study demonstrated that the serum creatinine determined the maximum AKIN stage achieved for 95% of patients.6 Third, serum creatinine values were obtained as a part of clinical practice. This may have provided some ascertainment bias towards AKI and evaluation of its severity. Fourth, like any observational study, we may have residual confounding from known and unknown variables which may attenuate the relationship between AKI duration and mortality. Finally, we did not have any data from the time after discharge until the time of death. Thus, we do not know the intermediate outcomes, effects of treatment and mechanisms of death of patients in this cohort.

In conclusion, the duration of AKI is independently associated with long-term mortality and may provide additional prognostic information than magnitude of serum creatinine alone in patients who survive AKI after hospitalization for non-cardiac surgery. These data need to be validated in other settings of AKI, and if found to be true, duration of AKI should be incorporated into the consensus definitions of AKI and utilized in clinical studies of AKI in the future.

CONCISE METHODS

This study was conducted and reported according to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) consensus statement.22

Data Sources and Patients

The Veterans Affairs (VA) National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) was established in 1994 for continuous quality improvement with non-cardiac surgery in the United States. The NSQIP is the first validated, comprehensive, national outcome-based, and peer-controlled program for measuring and improving quality of non-cardiac surgical care. Automated electronic medical record data extraction and standardized manual data collection by NSQIP surgical nurse reviewers provide extensive preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative data on patients undergoing non-cardiac operations at 123 VA medical centers.23 We supplemented NSQIP data by merging in additional laboratory data (e.g., serum creatinine) obtained from the VA Decision Support System at the Austin Information Technology Center in Austin, Texas.

All diabetic Veteran patients with both pre- and post-operative serum creatinine values yet without pre-operative AKI or ESRD that underwent non-cardiac surgery operations between October 1, 2000 and September 30, 2004 were eligible for this study. We chose to only study diabetic patients in order to enrich the incidence of AKI in the cohort. We excluded 952 with metastatic cancer because of short-life expectancy, and 2651 patients who died during their hospital stay. If patients had multiple operations, only the first surgery was included for analysis. The final study population consisted of 35,302 patients.

Data Collection and Measurement

Predictor Variables

The magnitude of AKI was determined according to the percentage increase in creatinine between the pre-operative value (outpatient value within 6 months prior to surgery) and the maximum value within 14 days after the surgery. Individuals were stratified by three levels of AKI magnitude according to the AKIN staging criteria.3 Patients that were initiated on renal replacement therapy (RRT) were categorized as ‘failure’ regardless of the change in their serum creatinine values. AKI duration was determined by the number of days that subjects met at least the AKIN Stage 1 definition. A priori, AKI duration was categorized into 3 strata: Short (≤ 2 days), Medium (3-6 days), Long (≥ 7 days). We chose these thresholds based on our clinical experience with prerenal and intrinsic AKI. Patients who required RRT were categorized as long duration, regardless of the number of days that the serum creatinine remained elevated. For supplementary analyses, we also examined the relationship between recovery of AKI, duration of AKI, and long-term survival. Recovery of AKI was defined as those with AKI who had a discharge serum creatinine (i.e., last creatinine value available prior to discharge) that was no more than 0.2 mg/dL higher than the pre-operative serum creatinine value.

Outcome Variables

The VA National Death Index and the Beneficiary Identification and Records Locator Subsystem (BIRLS) database were used to ascertain time to death of patients who survived hospitalization after non-cardiac surgery. Data on survival time was missing from < 7% of patients without AKI, and from < 4% of patients with AKI.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons across the groups on baseline characteristics were performed using analysis of variance for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Unadjusted survival time (from the time of hospital discharge) among patients with differing severities and durations of AKI was examined using the Kaplan-Meier method, including median survival times. In subset analyses, log-rank tests were performed to test for equality of survivorship by AKI severity and duration. Also, we conducted supplementary Kaplan-Meier survival analyses utilizing only patients with ≥ 7 post-op serum creatinine values. Cox Proportional Hazards regression analysis was employed to evaluate the association between AKI by severity and duration and long-term survival while adjusting for potential confounders. Functional forms of each of the variables in the model were checked and log transformation and construction of categorical variables from continuous variables were employed where appropriate. Final model selection was employed via a non-automated backward selection technique, in which each of the covariates shown in Table 1 were removed from an all-inclusive model one at a time. Likelihood ratio tests were performed to ensure that omission of each covariate did not significant increase the value of the -2 log likelihood. The proportional hazards assumption was verified by assessment of Schoenfeld residuals and the log-cumulative hazard function vs. log of time. Goodness of fit was verified via plots of Cox-Snell, Martingale, and deviance residuals. Data are presented as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were performed using SAS software (Version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Kaplan-Meier curves used in publication were graphed in STATA (Version 10.1).

Table 2.

Incidence of AKI by AKIN Stage (Magnitude) Stratified by Duration of AKI

| AKI Duration | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AKIN Stage | Short | Medium | Long |

| 1 | 3810 (74.6%) | 1050 (20.6%) | 249 (4.9%) |

| 2 | 294 (38.7%) | 266 (35.0%) | 200 (26.3%) |

| 3 | 101 (26.0%) | 63 (16.2%) | 224 (57.7%) |

AKI- acute kidney injury

AKIN- acute kidney injury network

Short: ≤ 2 days, Medium: 3-6 days, Long: ≥ 7 days

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

The study was approved by the IRB at VA Connecticut Healthcare System and by the Surgical Quality Data Use Group of NSQIP.

Grant Support: The study was funded by a grant from the Clinical Epidemiology Research Center (CERC), VA Connecticut Healthcare System, West Haven, CT. Dr. Coca is funded by the career development grant K23DK08013 from the National Institutes of Health, by the Hartford Foundation Center of Excellence in Aging at Yale Subspecialty Scholar Award, and by the American Society of Nephrology-ASP Junior Development Award in Geriatric Nephrology. Dr. Parikh is supported by the AKI grants RO1 HL085757 and UO1-DK082185 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest: None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(3):844–61. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05191107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, Mehta RL, Palevsky P, workgroup atnA Acute renal failure - definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the second international Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Critical Care. 2004;8(4):R205–R12. doi: 10.1186/cc2872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, et al. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagshaw SM, George C, Bellomo R. A comparison of the RIFLE and AKIN criteria for acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(5):1569–74. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuitunen A, Vento A, Suojaranta-Ylinen R, Pettila V. Acute renal failure after cardiac surgery: evaluation of the RIFLE classification. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(2):542–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopes JA, Fernandes P, Jorge S, et al. Acute kidney injury in intensive care unit patients: a comparison between the RIFLE and the Acute Kidney Injury Network classifications. Crit Care. 2008;12(4):R110. doi: 10.1186/cc6997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopes JA, Jorge S, Resina C, et al. Prognostic utility of RIFLE for acute renal failure in patients with sepsis. Crit Care. 2007;11(2):408. doi: 10.1186/cc5722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez Valdivieso JR, Bes-Rastrollo M, Monedero P, De Irala J, Lavilla FJ. Evaluation of the prognostic value of the risk, injury, failure, loss and end-stage renal failure (RIFLE) criteria for acute kidney injury. Nephrology (Carlton) 2008;13(5):361–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2008.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz DN, Bolgan I, Perazella MA, et al. North East Italian Prospective Hospital Renal Outcome Survey on Acute Kidney Injury (NEiPHROS-AKI): targeting the problem with the RIFLE Criteria. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(3):418–25. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03361006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perazella MA, Coca SG, Kanbay M, Brewster UC, Parikh CR. Diagnostic value of urine microscopy for differential diagnosis of acute kidney injury in hospitalized patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(6):1615–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02860608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonventre JV. Dedifferentiation and proliferation of surviving epithelial cells in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(Suppl 1):S55–61. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000067652.51441.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thadhani R, Pascual M, Bonventre JV. Acute renal failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(22):1448–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605303342207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liano F, Felipe C, Tenorio MT, et al. Long-term outcome of acute tubular necrosis: a contribution to its natural history. Kidney Int. 2007;71(7):679–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loef BG, Epema AH, Smilde TD, et al. Immediate postoperative renal function deterioration in cardiac surgical patients predicts in-hospital mortality and long-term survival. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(1):195–200. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2003100875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welten GM, Schouten O, Chonchol M, et al. Temporary worsening of renal function after aortic surgery is associated with higher long-term mortality. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(2):219–28. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitt R, Cantley LG. The impact of aging on kidney repair. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294(6):F1265–72. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00543.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmitt R, Coca S, Kanbay M, Tinetti ME, Cantley LG, Parikh CR. Recovery of kidney function after acute kidney injury in the elderly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52(2):262–71. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmitt R, Marlier A, Cantley LG. Zag Expression during Aging Suppresses Proliferation after Kidney Injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19(12):2375–83. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008010035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juhlin T, Bjorkman S, Gunnarsson B, Fyge A, Roth B, Hoglund P. Acute administration of diclofenac, but possibly not long term low dose aspirin, causes detrimental renal effects in heart failure patients treated with ACE-inhibitors. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004;6(7):909–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juhlin T, Bjorkman S, Hoglund P. Cyclooxygenase inhibition causes marked impairment of renal function in elderly subjects treated with diuretics and ACE-inhibitors. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7(6):1049–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juhlin T, Erhardt LR, Ottosson H, Jonsson BA, Hoglund P. Treatments with losartan or enalapril are equally sensitive to deterioration in renal function from cyclooxygenase inhibition. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9(2):191–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, et al. The National Veterans Administration Surgical Risk Study: risk adjustment for the comparative assessment of the quality of surgical care. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180(5):519–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]