Abstract

Background: The safety and efficacy of upfront sunitinib, before nephrectomy in metastatic clear cell renal cancer (mCRC), has not been prospectively evaluated.

Methods: Two prospective single-arm phase II studies investigated either two cycles (study A: n = 19) or three cycles (study B: n = 33) of sunitinib before nephrectomy in mCRC.

Results: Overall, 38 of 52 (73%) of patients obtained clinical benefit (by RECIST) before surgery. The partial response rate of the primary tumour was 6% [median reduction in longest diameter of 12% (range 8%−35%)]. No patients became ineligible due to local progression of disease. A nephrectomy was carried out in 37 (71%) of patients. Necrosis (>50%) was a prominent feature at nephrectomy in 49%. Surgical complications (Clavien–Dindo classification) occurred in 10 (27%) patients, including one death (3%). The median blood loss and surgical time were 725 (90–4200) ml and 189 (70–420) min, respectively. The median progression-free survival was 8 months (95% confidence interval 6–15 months). A comparison of two versus three pre-surgery cycles showed no significant difference in terms of surgical complications or efficacy.

Conclusions: Nephrectomy after upfront sunitinib can be carried out safely. It obtains control of disease. Randomised studies are required to address if this approach is beneficial.

Keywords: metastatic renal cancer, nephrectomy, sunitinib

introduction

The introduction of targeted antiangiogenic agents has revolutionised the treatment of metastatic clear cell renal cancer (mCRC) [1–7]. Sunitinib, a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), is established as first-line therapy in metastatic disease [2].

The role of cytoreductive nephrectomy in mCRC in the era of targeted therapy is not well established. The randomised data supporting its use comes from the pre-targeted therapy era, when less effective immune therapy was standard care [8, 9]. The vast majority of patients in the randomised sunitinib studies have had a nephrectomy before therapy [10].

The timing of this nephrectomy is an area of great interest. Theoretically treating with upfront sunitinib before nephrectomy has advantages in mCRC. These include commencing systemic therapy more quickly to obtain disease control and down staging the primary tumour facilitating surgery [11]. It is also possible that this upfront approach selects out patients with rapidly progressive disease who may not benefit most from nephrectomy [12]. However, there are potential risks associated with upfront targeted therapy, such as delayed wound healing, local progression of disease before surgery and tumour regrowth in the interval off sunitinib during the nephrectomy [11–15]. For these reasons, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer 30073 randomised phase III study, comparing upfront sunitinib followed by nephrectomy against nephrectomy followed sunitinib will open in 2010. However, knowledge of the safety and efficacy of upfront sunitinib therapy before nephrectomy in prospective series is essential.

In this manuscript, two single-arm phase II prospective studies, evaluating upfront sunitinib before nephrectomy, are assessed together and individually to address these issues. The two studies were almost identical in terms of patient’s characteristics, design and end points. However, the number of cycles of upfront sunitinib given before nephrectomy (two vs three) and the treatment free interval before nephrectomy (1 vs 14 days) differ. This allows assessment of the optimal number of cycles before surgery and optimal treatment-free interval.

methods

study design and patients selection

This manuscript combines two open single-arm prospective studies with similar designs and end points. The studies, which are now closed, were combined to obtain more powerful and meaningful safety and efficacy data in this setting before the prospective randomised clinical trial commencing. Both studies consisted of previously untreated patients with newly diagnosed biopsy proven mCRC. Only patients with either intermediate-risk or poor-risk [Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) criteria [16]] disease were included in both studies. None of the patients had previously received any systemic therapy. Patients were given either two cycles (study A) or three cycles (study B) of sunitinib (50 mg p.o. od, 4 weeks on 2 weeks off) before a planned nephrectomy. After the nephrectomy, patients continued on sunitinib until progression. Imaging with computed tomography scan of the chest and abdomen was carried out before therapy and before and after surgery in both studies. Subsequent imaging was carried out on a 12 weekly basis after nephrectomy. Analysis of both studies was carried out centrally for all aspects including radiology [Dr Katani (RECIST v1.1)]. Those patients who did not have a nephrectomy, for either surgical reasons or through patient choice, continued on sunitinib until progression. Patients with progression of metastatic disease before nephrectomy did not undergo surgery. Analysis of both studies took place centrally in December 2009. Descriptive statistics were used to compare patients and groups. The overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS) were analysed using Kaplan–Meier plots. Univariate and multivariate analysis was carried out to identify prognostic factors associated with a poor outcome.

study A: design and patients characteristics

From June 2007 to August 2009, 19 patients were enrolled from The Netherlands Cancer Institute. Patients with untreated biopsy proven clear cell renal cancer received two cycles of sunitinib therapy before a nephrectomy, which took place 24 hr after the last dose of sunitinib. A further minimum 21-day enforced treatment break occurred after nephrectomy, before restarting sunitinib therapy.

study B: design and patients characteristics

From January 2008 to August 2009, 33 patients were enrolled from two treatment centres in the UK. Patients received three cycles of sunitinib before planned nephrectomy. Surgery took place 14 days after the last dose of sunitinib therapy (day 28 cycle 3). Sunitinib was planned to start a minimum of 14 days after the surgery.

trial statistics and ethical considerations

Both studies were followed by a Simon’s 2-stage design. The primary end point of study A was response rate to the primary tumour, while in study B, it was clinical benefit to the primary tumour. Study A did not reach the 2nd stage due to the low response rate, while study B progressed to the 2nd stage and met its primary end point of clinical benefit. These data are given in Table 2. Both studies were reviewed and approved by an established independent national ethical committee and were carried out according to good clinical practice guidelines.

Table 2.

Clinical and radiological features before and during therapy

| Overall | After 2 cycles of sunitinib | After 3 cycles of sunitinib | Intermediate-risk disease | Poor-risk disease | |

| n | 52 | 19 | 33 | 35 | 17 |

| Overall response (RECIST) at the time of surgery, n (%) | |||||

| PR | 5 (10) | 2 (11) | 3 (9) | 4 (11) | 1 (6) |

| SD | 33 (63) | 13 (68) | 20 (61) | 23 (66) | 10 (58) |

| PD | 12 (23) | 4 (21) | 8 (24) | 7 (20) | 5 (29) |

| Not evaluablea | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 1 (6) |

| Response of renal tumour (RECIST) at the time of surgery, n (%) | |||||

| PR | 3 (4) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) | 3 (9) | 0 (0) |

| SD | 46 (94) | 16 (95) | 30 (90) | 30 (88) | 16 (94) |

| PD | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Not evaluable | 3 (2) | 1 (0) | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 1 (6) |

| Median shrinkage of primary tumour (%) | 12 % (+ 8 to −35) | 11% (+ 1 to −28) | 12% (+ 6 to −35) | 13% (+ 8 to −35) | 10% (+6 to−28) |

| Response in metastatic sites (RECIST), n (%) | |||||

| PR | 14 (27) | 5 (26) | 9 (28) | 9 (23) | 5 (29) |

| SD | 21 (40) | 10 (53) | 11 (33) | 16 (20) | 5 (29) |

| Tumor growth/PD | 12 (22) | 4 (21) | 8 (24) | 7 (20) | 5 (29) |

| Not evaluableb | 5 (11) | 0 (0) | 5 (15) | 3 (9) | 2 (12) |

| Median progression-free survival (months) with 95% CIs | 8 months (6–15) | 7 months (5–19) | 8 months (6–15) | 10 months (6–NA) | 7 months (6–NA) |

| Cause of death, n (%) | |||||

| Total | 22 (46) | 8 (41) | 14 (42) | 12 (34) | 10 (58) |

| Renal cancer | 18 (34) | 7 (36) | 11 (33) | 9 (26) | 9 (52) |

| Surgery related | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Otherc | 3 (6) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | 1 (6) |

Stopped sunitinib and non-cancer-related death before assessment.

Patients with bone only as a site of metastatic were not evaluable in terms of size of tumour reduction (n = 3). These data also include two non-assessable patients (infection death and changed therapy).

CI, confidence interval; NA, not achieved; PD, progression of disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Euthanasia/suicide (two) and infection.

results

patients characteristics and outcome

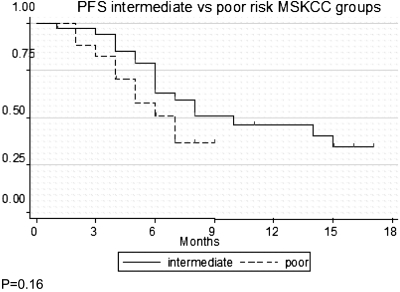

A total of 52 patients with clear cell tumours were enrolled into these two studies and started sunitinib therapy (19 from study A and 33 from study B) (Table 1 and Figure 1). The characteristics of these patients is summarised in Table 1. Forty-one (77%) were male and the median age was 60.5 years (range 37–78). Seventeen (33%) had MSKCC poor-risk disease and 35 (67%) had intermediate-risk disease. Study B included more patients with poor-risk disease [16 (50%) versus 1 (5%)]. Median longest diameter of the primary tumour before treatment was 9.45 cm (range 4.2–23.2 cm). The median PFS for the cohort was 8 months (95% confidence interval 5–15) and the median overall survival has not been reached. Univariate and multivariate analysis showed that the number of metastatic sites was the only factor associated with a shorter PFS (P < 0.05). Other factors such as study design (A versus B), MSKCC prognostic group (intermediate versus poor), gender and age were not significant (P > 0.05 for each).

Table 1.

Patients demographics and characteristics at diagnosis

| Combined data | Study A: 2 sunitinib cycles | Study B: 3 sunitinib cycles | |

| Number of patients | 52 | 19 (37%) | 33 (63%) |

| Age | 60.5 (range 37–78) | 51 (range 37–78) | 62 (range 44–76) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 41 (77) | 15 (79) | 26 (79) |

| Female | 11 (23) | 4 (21) | 7 (21) |

| MSKCC prognostic risk, n (%) | |||

| Intermediate | 35 (66) | 18 (95) | 17 (52) |

| Poor | 17 (33) | 1 (5) | 16 (48) |

| Number of metastatic sites, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 15 (29) | 4 (21) | 11 (33) |

| 2 | 17 (33) | 6 (32) | 11 (33) |

| 3+ | 20 (38) | 9 (47) | 11 (33) |

| Sites of metastatic disease on CT, n (%) | |||

| Lung | 46 (88) | 18 (95) | 28 (84) |

| Bone | 16 (31) | 3 (15) | 13 (33) |

| Lymph node | 26 (50) | 9 (47) | 17 (52) |

| Liver | 7 (13) | 3 (15) | 4 (12) |

| Other | 12 (27) | 4 (21) | 8 (24) |

| Primary tumor size [longest diameter (median in cm)] | 9.45 (4.2–23.2) | 10.3 (6.8–23.2) | 9.9 (4.2–18.7) |

| Histology prior to surgery, n (%) | |||

| Clear cell | 52 | 19 | 33 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 |

CT, computed tomography scan; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Figure 1.

Progression-free survival curves. Some patients were not included: (A) rapid PD/death (n = 2). Patients changed to sorafenib (n = 1). (B) Bone metastasis only (n = 3) rapid PD/death (n = 3). Patients changed to sorafenib (n = 1).

radiological outcomes with upfront sunitinib before surgery

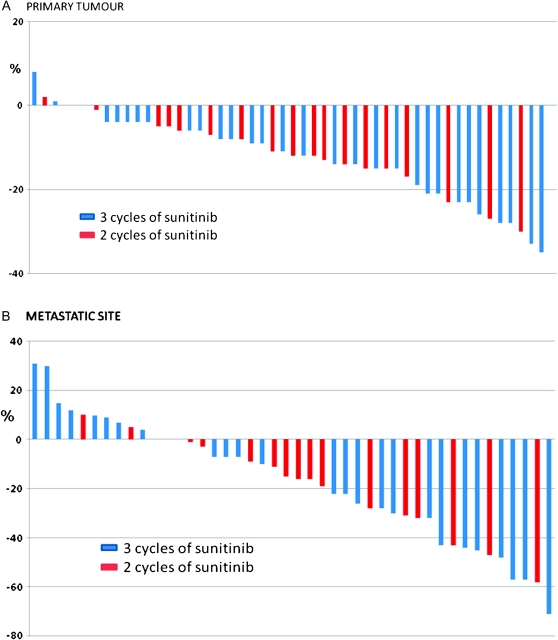

All but two of the patients were assessable radioligically before surgery (Table 2 and Figure 2A and B). One of these patients died of pneumonia within 4 weeks of starting sunitinib, while the other patient stopped therapy and switched to another TKI (sorafenib) during cycle 1 of sunitinib. Upfront therapy was associated with a median reduction of the longest diameter of the primary tumour of 12% (range 8%−35%). A partial response by RECIST criteria to the primary tumour occurred in three patients (6%). No patients had progression of the renal tumour by RECIST or became ineligible. The number of cycles did not have a significant effect on the reduction of the primary tumour (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Percentage change of the tumours with sunitinib (A) primary tumour (measures the longest diameter of the primary tumour) (B) metastatic site [measures only the combined metastatic sites (RECIST v1.1)]

Overall, a clinical benefit (by RECIST) occurred in 38 (73%) of patients (79% in study A and 70% in study B). Five (10%) patients achieved an overall partial response, while 12 (24%) had progression of disease at the time of surgery. The partial response rate for the metastatic sites was higher (27%) than that seen in the primary tumour (6%) (P < 0.05) (Figure 2A and B). The number of cycles of therapy before surgery and MSKCC risk group did not have a significant effect on the response rate (P > 0.05).

surgical outcomes and complications

Thirty-seven (70%) of the 53 patients had a radical nephrectomy (Table 3). The reasons for not undergoing a nephrectomy were progression of systemic disease (n = 9), patients choice (n = 3) and being unfit for surgery at the time of nephrectomy (n = 2). The two further patients who were not assessable for radiological end points (described above) did not have surgery (early death due to infection and switched therapy).

Table 3.

Surgical data for patients receiving nephrectomy after upfront sunitinib

| Total | 1-day off sunitinib pre-surgery | 14-days off sunitinib pre-surgery | |

| Nephrectomy data | |||

| Total | 37 | 16 | 21 |

| Open, n (%) | 31 (84) | 15 (94) | 16 (76) |

| Laparoscopic, n (%) | 4 (11) | 0 (0) | 4 (25) |

| Laparoscopic converted to open, n (%) | 2 (5) | 1 (7) | 1 (6) |

| Reason for no nephrectomy | |||

| Patient choice, n (%) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| PD of systemic disease, n (%) | 9 (24) | 3 (19) | 6 (29) |

| PD of renal tumour, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Surgically unfit, n (%) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| Other, n (%)a | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| Surgical outcome | |||

| Blood loss (ml) | 725 (90–4200) | 635 (80–3000) | 775 (90–4700) |

| Surgical time (min) | 189 (70–420) | 180 (80–230) | 195 (70–420) |

| Duration in hospital (days) | 8 (4–36) | 8 (7–17) | 7 (4–36) |

| T stage at nephrectomy, n (%) | |||

| T1 | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| T2 | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| T3a | 26 (70) | 13 (80) | 13 (62) |

| T3b | 4 (11) | 1 (7) | 3 (14) |

| T4 | 4 (11) | 2 (13) | 2 (10) |

| Necrosis at surgery, n (%) | |||

| <25% | 13 (35) | 7 (44) | 6 (29) |

| 25–50% | 6 (16) | 2 (13) | 4 (19) |

| >50 | 18 (49) | 7 (44) | 11 (69) |

| Grade at surgery, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 16 (43) | 6 (37) | 10 (48) |

| 3 | 17 (46) | 9 (56) | 8 (38) |

| 4 | 4 (11) | 1 (7) | 3 (14) |

| Surgical complications b(Clavien–Dindo classification), n (%) | |||

| 0 | 27 (73) | 12 (75) | 15 (70) |

| I | 6 (16) | 4 (25) | 2 (10) |

| II | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| III | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| IV | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| V | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Median time from surgery to restarting sunitinib therapy (days) | 21 (range 14–82) | 24.5 (range 21–49) | 16 (range 21–82) |

| Median time off sunitinib due to surgery (days) | 28 (range 22–96) | 26 (range 22–51) | 28 (range 26–96) |

| Effect of surgery on creatinine (median values) | |||

| Before nephrectomy | 78 (57–135) | 88 (57–103) | 75 (64–135) |

| After nephrectomy | 109 (69–221c)* | 110 (83–157) | 108 (69–221c) |

One patients died of infection and the other stopped sunitinib and refused surgery after 4 weeks of therapy.

I = delayed wound healing (X2) and oedema, II = none, III = bleeding, IV = renal failure and hypotension and V = respiratory failure post o.p.

One dialysis dependant.

*P > 0.05.

PD, progression of disease.

The median blood loss was 725 ml (range 90–4200 ml), while the duration of surgery and median hospital stay was 189 min (range 70–420 min) and 8 days (range 4–36 days), respectively. Surgical complications occurred in 10 (27%) patients, including delayed wound healing (n = 5) (16%) (Clavien I), post-operative oedema (1) (Clavien I), bleeding requiring surgical reintervention (1) (Clavien IIIb), renal failure requiring dialysis (1) (Clavien IVa) and post-operative hypotension requiring ICU admission (1) (Clavien IVa). There was a post-operative death due to respiratory failure (Clavien V). A significant increase in the plasma creatinine after surgery from 78 μmol/l (57–135) to 109 μmol/l (69–221) occurred in this cohort of patients (P = 0.02). A comparison of the complications seen with either 1 or 14 days off treatment before surgery showed no significant differences.

Clear cell renal cancer was confirmed in 100% of patients at surgery. The majority of tumours were grade 2 (43%) or 3 (46%). Forty-nine percent of tumours contained >50% necrosis at the time of surgery. Tissue fibrosis was a prominent feature in 13 (62%) cases in study B, this did not occur in study A.

sunitinib therapy post-operative

The median time from nephrectomy to restarting sunitinib was 21 days (range 14–82 days) and median duration off therapy, including pretreatment break was 28 days (range 22–96 days) (Table 3).

A significant proportion of patients had progression of disease by RECIST criteria 8/32 (25%) after the surgery-related treatment break. Reintroduction of sunitinib therapy resulted in stabilisation of disease in 71% (5/7) of these patients when compared with the metastatic sites of the last staging before surgery.

At progression, three patients received second-line therapy [one with sorafenib and two with mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors]. This was largely due to the lack of availability of second-line therapy during this study period.

sunitinib toxicity before planned nephrectomy

Grade 3 or more toxicity occurred in 16 (30%) patients before nephrectomy and 11 (21%) had a dose reduction during this period of time. Toxicity did not delay scheduled surgery in any case. The most commonly encountered toxicity were mucositis (15%), hand and foot syndrome (11%), fatigue (9%), hypertension (6%) and diarrhoea (6%). These results are in line with previous results with sunitinib [2].

discussion

To our knowledge, these are the first studies to prospectively report on the safety and efficacy of upfront sunitinib in metastatic disease. The studies were very similar in terms of patient population, design and end points. Although they were not designed to be assessed together, combining them allows more robust and powerful data in this setting. This is particularly important to identify the optimal period of sunitinib before surgery and time off drug pre-surgery, which will help guide the randomised study which is due to start later this year. Results showed that this approach is surgically safe and promising in terms of efficacy, with the majority (73%) obtaining a clinical benefit (stable disease, partial response and complete response) and PFS being in line with that available for intermediate-risk and poor-risk MSKCC disease treated with sunitinib in mCRC [2, 10].

One of the challenges in this area surrounds trial design. These trials were among the first in the field and other end points such as PFS may have been preferential. This is underlined by the lack of RECIST response rates in the primary tumour, which is in line with the retrospective reports in this area [11–15], and in contrast to the higher response rates in the metastatic sites (Figure 2A and B). Despite this lack of responses in the primary tumour, the majority of patients obtained some tumour shrinkage and none became inoperable, which is reassuring.

There are other potential advantages of this upfront approach despite the lack of primary response rates. This approach specifically allows patients with a high metastatic burden and/or MSKCC poor-risk disease to start sunitinib early with the hope of identifying those who benefit from treatment and subsequent surgery, while sparing those with primary refractory disease a nephrectomy. Table 3 and the multivariate analysis showed that patients with poor-risk disease had impressive response and PFS rates and did not have a significantly worse outcome than the intermediate group. This is reassuring for this group of patients, where outcome remains poor [2, 10]. Temsirolimus has more robust randomised data than sunitinib in the poor-risk population [5]. However, sunitinib is widely used and recommend here [10, 17]. There are currently no prospective data reporting the effect of mTOR inhibitors in this upfront setting and retrospective analysis in the poor-risk population failed to demonstrate a clear advantage for nephrectomy with temsirolimus [5]. This questions the role of nephrectomy here; however, prospective randomised trials are required to obtain quality data. Temsirolimus was not available in either country during the period of the trial and was therefore not offered to patients.

There were also a number of patients who declined or were not deemed fit enough for nephrectomy, these patients were benefiting from sunitinib and it was felt that the risks of interrupting treatment and surgery outweighed the benefits. Without randomised data, it is not possible to determine whether this approach is optimal for either of these groups. However, it does appear to have some potential advantages.

Nephrectomy occurred in 37 (70%) of the patients. Overall, the complication rate, surgical time, duration in hospital and blood loss were in line with untreated nephrectomies in mCRC [8]. Indeed, in recent retrospective series describing upfront nephrectomy, peri-operative mortality occurred in 6% [18]. Thus, nephrectomy in this population is associated with significant risks irrespective of its timing.

Delayed wound healing, which has been highlighted as a potential concern by retrospective series, and other angiogenic targeted therapies in this area (bevacizumab is associated with a 20% incidence [12]) occurred in five patients (13%).

Fibrosis was a prominent feature during nephrectomy after three cycles of therapy but not two. This may related to the length of exposure to sunitinib and requires further investigation.

A concern with this upfront approach is the potential for rebound tumour growth during the treatment interruption for nephrectomy [19]. In this study, 25% of patients experience progression of disease in the short time off treatment after the nephrectomy. Subsequent stabilisation did occur (71%) after the drug was reintroduced and two patients had a response by RECIST criteria at this point, but numbers were small. It is unknown what effect this progression has on overall survival, which can be only addressed in the randomised study. However, progression rates of 30% occur after nephrectomy in patients who were not previously treated with sunitinib putting these results in context [18]. This figure of 30% could potentially be used as a benchmark of safety in this area. It is unknown whether this progression is a consequence of growth factor release and compromised immunity following nephrectomy, rebound after withdrawal of sunitinib or a combination of both. This important issue has implications for individuals stopping sunitinib for significant periods of time and requires further evaluation, especially in light of the supportive preclinical data in this area [19].

Specific differences in the design of the two studies allow us to compare two versus three cycles of upfront therapy and whether 1-day off drug was adequate to avoid surgical complications. Results showed that there were no specific differences between two or three cycles of treatment, although a lower proportion of patients who received three cycles had surgery, and at surgery, peritumoral fibrosis was a prominent feature in this group. This subjective finding may be due to the higher percentage of poor-risk patients or the more prolonged time on therapy in study B. Importantly, the 1-day treatment gap before surgery appears safe which is reassuring, as this reduces the potential time off therapy.

It is not clear from this work whether nephrectomy should be carried out in those patients with initial progression of disease to facilitate further response to treatment. At first glance, approach appears counterintuitive, in that patients with aggressive sunitinib-resistant disease are likely to experience further systemic progression and subsequent deterioration during the surgery-related treatment breaks. This could potentially be the focus of work in the future.

The number of metastatic sites was the only significant factor to predict PFS in multivariate analysis. Previous work with bevacizumab in this setting suggested that the presence of widespread disease is associated with a poor outcome here [12]. This underlines the point that there are likely to be subgroups of patients who do not benefit from nephrectomy, which is being addressed prospectively.

Although the two studies were remarkably similar, they were not initially designed with the intention of combining the data, which is a shortcoming of this work. However, central meta-analysis of all aspects of the studies was carried out to reduce potential bias. Both the studies were a prelude to the randomised trial, investigating interval nephrectomy to give insight into the safety and potential advantages of this approach. Together, they demonstrate that either two or three cycles of sunitinib before surgery is surgically safe and that only 1 day off treatment before surgery is optimal. This approach appears attractive, especially for patients with a large tumour burden and/or poor-risk disease. However, the results of the randomised trial will be required before it can be determined if it is beneficial.

disclosure

AB and TP have participated in advisory boards for Pfizer in 2009. Pfizer gave educational grant to support this work.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Experimental Cancer Medicine Centres at Barts and the London and University College Hospital London for their support and Pfizer, who supplied research grants for both studies.

Authors contributions.

Concept: TP, IK, SC and AB.

Study design: TP, AB, JS.

Patients recruitment and intervention: TP, IK, CB and SC, SH, JP, NS, JS, KB, AS, TO, LL, DB, JH, AB, PN and LB.

Data analysis: TP, IK and AB.

Manuscript writing: TP, AB and LL.

Final approval of manuscript: TP, IK, CB, SC, SH, JP, NS, JS, KB, AS, TO, LL, DB, JH and AB.

funding

TP and AB received educational grants from Pfizer to help in the running of these studies.

References

- 1.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, et al. Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9637):449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):125–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rini BI, Halabi S, Rosenberg JE, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa compared with interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: CALGB 90206. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5422–5428. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2271–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ratain MJ, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Phase II placebo-controlled randomized discontinuation trial of sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(16):2505–2512. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sternberg CN, Szczylik C, Lee E, et al. A randomized, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib in treatment-naive and cytokine-pretreated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. (Abstr 5021) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, et al. Nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone for metastatic renal-cell cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1655–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mickisch GH, Garin A, van Poppel H, et al. Radical nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2001;358:966–970. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)06103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gore ME, Szczylik C, Porta C, et al. Safety and efficacy of sunitinib for metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: an expanded-access trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(8):757–763. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70162-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Veldt AA, Meijerink MR, van den Eertwegh AJ, et al. Sunitinib for treatment of advanced renal cell cancer: primary tumor response. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2431–2436. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonasch E, Wood CG, Matin SF, et al. Phase II presurgical feasibility study of bevacizumab in untreated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4076–4081. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas AA, Rini BI, Stephenson AJ, et al. Surgical resection of renal cell carcinoma after targeted therapy. J Urol. 2009;182(3):881–886. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margulis V, Matin SF, Tannir N, et al. Surgical morbidity associated with administration of targeted molecular therapies before cytoreductive nephrectomy or resection of locally recurrent renal cellcarcinoma. J Urol. 2008;180:94. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shuch B, Riggs SB, LaRochelle JC, et al. Neoadjuvant targeted therapy and advanced kidney cancer: observations and implications for a new treatment paradigm. BJU Int. 2008;102:692. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Motzer RJ, Mazumdar M, Bacik J, et al. Survival and prognostic stratification of 670 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(8):2530–2540. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kutikov A, Uzzo RG, Caraway A, et al. Use of systemic therapy and factors affecting survival for patients undergoing cytoreductive nephrectomy. BJU Int. 2010;106(2):218–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09079.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nathan P, Wagstaff J, Porfiri E, et al. UK guidelines for the systemic treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2009;70(5):284–286. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2009.70.5.42228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebos JM, Lee CR, Cruz-Munoz W, et al. Accelerated metastasis after short-term treatment with a potent inhibitor of tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2009;15(3):232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]