Abstract

Background: Rituximab has been associated with hepatitis B virus reactivation (HBV-R). However, the characteristics and scope of this association remain largely undefined.

Methods: We completed a comprehensive literature search of all published rituximab-associated HBV-R cases and from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) MedWatch database. Literature and FDA cases were compared for completeness, and a meta-analysis was completed.

Results: One hundred and eighty-three unique cases of rituximab-associated HBV-R were identified from the literature (n = 27 case reports, n = 156 case series). The time from last rituximab to reactivation was 3 months (range 0–12), although 29% occurred >6 months after last rituximab. Within FDA data (n = 118 cases), there was a strong signal for rituximab-associated HBV-R [proportional reporting ratio = 28.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 23.9–34.1; Empiric Bayes Geometric Mean = 26.4, 95% CI 21.4–31.1]. However, the completeness of data in FDA reports was significantly inferior compared with literature cases (P < 0.0001). Among HBV core antibody (HBcAb(+)) series, the pooled effect of rituximab-based therapy showed a significantly increased risk of HBV-R compared with nonrituximab-treated patients (odds ratio 5.73, 95% CI 2.01–16.33; Z = 3.33, P = 0.0009) without heterogeneity (χ2 = 2.12, P = 0.5473).

Conclusions: The FDA AERS provided strong HBV-R safety signals; however, literature-based cases provided a significantly more complete description. Furthermore, meta-analysis of HBcAb(+) series identified a more than fivefold increased rate of rituximab-associated HBV-R.

Keywords: FDA, HBV reactivation, hepatitis B virus, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, rituximab

introduction

Although effective vaccines for prevention of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection have been available for >25 years, nearly 400 million persons are infected worldwide [1, 2]. Many individuals infected with active HBV maintain a persistent carrier state, defined as serologic presence of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg+). Immunosuppressive therapy with glucocorticosteroids and immunosuppressant drugs or with anticancer chemotherapy has been shown to cause a flare or ‘reactivation’ of HBV that may lead to liver failure and death.

Without prophylaxis, hepatitis B virus reactivation (HBV-R) occurs in up to 85% of HBsAg(+) non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) patients who receive steroid-containing chemotherapy with associated HBV-related death rates of 30%–50% [3–8]. With appropriate antiviral prophylaxis, chemotherapy-related HBV-R is significantly decreased [9–11], although the risk of reactivation and liver failure/death remains [12, 13]. Many patients with prior HBV infection have cleared the virus serologically; these patients typically have core HBV antibody-positive (HBcAb+) and HBsAg(−) disease. When treated with chemotherapy and/or steroids, these patients have a low risk of HBV-R (<1% to 2%) [6, 14]. The risk of rituximab-associated HBV-R in HBcAb+ patients has not been adequately analyzed or quantified.

The anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, rituximab, has revolutionalized the treatment of NHL. Rituximab is an overall well-tolerated drug with minimal late toxicity. However, recent data have suggested an increased risk of infectious complications, in particular viral mediated [15]. In July 2004, based on three case reports [16–18], the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and manufacturers of rituximab issued a ‘Dear Health Care Professional’ letter regarding rituximab-associated HBV-R and encouraged health care professionals to submit any related reports to the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) MedWatch system [19]. Since that time, multiple case reports and several retrospective series of rituximab-induced HBV-R have been reported in the literature and submitted to the FDA. In addition, several recent reports have documented fatal ‘late’ HBV-R occurring >6 months after completion of rituximab [20–24], which is an unusual occurrence with chemotherapy-associated HBV-R (i.e. without rituximab) [14]. Despite these reports, the characteristics and scope of rituximab-induced HBV-R remain poorly characterized. Moreover, the absolute risk that rituximab contributes to HBV-R in HBcAb(+) or HBsAg(+) patient populations is not known.

Through a systematic literature review, we examined the characteristics, incidence, and clinical outcomes of patients with lymphoproliferative diseases, who developed HBV-R after exposure to rituximab-based therapy. Further, we analyzed the quality and completeness of case reports available in the medical literature compared with those reported to the FDA. We also completed a meta-analysis in order to estimate the risk that rituximab adds to HBV-R.

methods

data sources

The literature search covered the period from November 1997, the date rituximab received its initial FDA approval, through 30 September 2009 (Medline and EMBASE MeSH search terms: hepatitis, HBV, rituximab, monoclonal antibody, lymphoma, and lymphoproliferative diseases, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Data sources included two surveillance cases at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, two cases at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan, and 183 unique reports from the medical literature. The FDA AERS data was from the same time period (November 1997 through September 2009), using all Medical Dictionary for Drug Regulatory Affairs preferred terms that contained ‘HBV’ and was limited to patients whose documented indication for rituximab included lymphoproliferative diagnoses. We identified 118 unique cases in the FDA MedWatch database (104 of which submitted as ‘expedited’ reports).

study selection

Three independent reviewers extracted data from all case reports, case series, and cohort series that reported an association of rituximab with HBV-R. Inclusion criteria for rituximab-associated HBV-R included receipt of at least one dose of rituximab (alone or combined with other therapy) for the treatment of a lymphoproliferative disease before HBV-R and no history of prior solid organ transplant or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Duplicate reports were identified based on demographic and clinical criteria, including age, sex, concomitantly administered drugs, and underlying illnesses. Two literature reports of rituximab-associated HBV-R not associated with NHL were excluded (vasculitis [25] and gloumerulonephritis [26]).

For literature reports, HBV-R was defined as a >10-fold rise in serum HBV DNA levels with an accompanying increase in serum ALT compared with baseline. HBV-related hepatitis was defined as an increase in serum ALT more than two times greater than baseline and a 10-fold increase in serum HBV DNA levels, while HBV-related liver failure was defined as elevated serum ALT level together with prolonged prothrombin time or other evidence of coagulopathy. HBV-related death was defined as death of a patient, who had documented HBV-R, evidence of fulminant liver failure, and no other apparent cause of death.

data analysis

The statistical signal strength of the association between rituximab exposure in lymphoproliferative patients and HBV-R was calculated using the proportional reporting ratio (PRR) and the Empirical Bayesian Geometric Mean (EBGM) [27–29]. The PRR and EBGM were calculated by identifying all patients in the FDA AERS from rituximab’s initial FDA approval, who were treated for a lymphoproliferative disease. These signal detection calculations provide assessments of the disproportionality of the frequency of a specific reaction for a given drug in comparison to what would be predicted for that drug based on reports of that adverse effect associated with all other drugs in the dataset. A completeness analysis was carried out comparing completeness of cases submitted to the FDA AERS database compared with cases abstracted from the medical literature or from our active surveillance efforts; we prespecified the covariates to be collected prior to data abstraction. To compare frequencies, we used Fisher’s exact test. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was utilized to analyze differences in patient ages and time to HBV-R. We used Thomas Lumley’s Bioconductor package ‘rmeta’, version 2.16: to carry the calculations for the meta-analysis of the incidence of rituximab-associated HBV-R, to conduct the Mantel–Haenszel analysis [and confidence intervals (CIs)], to carry the Woolf test for heterogeneity, and to create the forest plots. In order to obtain forest plots for studies that contained a zero count, we added a single count to all cells in the corresponding 2 × 2 table.

results

patients’ characteristics

From 1997 through 2009, 183 rituximab-associated HBV-R unique cases were reported in the medical literature: 27 published as case reports and 156 through case series. The vast majority (99%) of these cases were reported after 2004 with 85% reported in the last 2 years. The 2 Northwestern cases, 2 Taiwan surveillance cases and 27 literature case reports were grouped together for purposes of analysis. In this group of 31 patients, 16 had HBcAb(+) (HBsAg−) rituximab-associated HBV- R, while 15 had HBsAg(+) (Tables 1 and 2). The median age at HBV-R was 55 years, range 21–79 (19 males/12 females); median age for HBcAb(+) patients was 60.5 years, and 42 years for the HBsAg(+) group (P = 0.05). Lymphoproliferative histologies were diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (n = 19), indolent NHL (n = 8), CLL (n = 2), and mantle-cell lymphoma (n = 2). Of note, 25 of these 31 patients had received concurrent immunosuppressive therapy (chemotherapy ± glucocorticosteroids n = 23, glucocorticosteroids alone n = 2), while only 6 cases involved single-agent rituximab treatment. Each of these six latter patients had received additional immunosuppressive therapy prior to rituximab treatment (at 2, 3, 4, 12, 24, and 34 months).

Table 1.

HBV core antibody-positive (surface antigen negative) rituximab-associated HBV reactivation: case reports

| Author | NHL type | Age/gender | Co-morbidity | Prior immunosuppressive therapy | Concurrent immune suppressants | Time to reactivate from first rituximab | Doses of rituximab | Time to reactivate from last rituximab | Liver outcome | Treatment of reactivation | Death |

| Dervite et al. [18] | FL | 69/M | None | 7 cycles CHEP and IFN, then 6 cycles HDAC (1 year prior) | Steroids for 6 months immediately prior | 7 months | 4 | 6 months | Hepatitis | NR | No |

| Westhoff et al. [16] | DLBCL | 73/M | None | CHOP 3 months prior | None | 3 months | NR | 1 month | Liver failure | Lamivudine | Yes |

| Niscola et al. [30] | CLL | 51/M | None | Fludarabine 34 months prior | None | 26 months | 10 | 1 month | Liver failure | Lamivudine | Yes |

| Sarrecchia et al.[31] | CLL | 53/M | HTN | Fludarabine 2 years prior | None | 4 months | 3 | 1 month | Liver failure | Lamivudine | Yes |

| Law et al [32] | DLBCL | 67/M | None | None | CHOP | 5 months | 8 | 1 month | Liver failure | Lamivudine | Yes |

| Sera et al. [33] | Indolent NHL | 59/M | None | CHOP 3 years prior, Dex and VCR 1 year prior | Etoposide, prednisone | 2 months | 3 | 0 month | Liver failure | Lamivudine | Yes |

| Ozgonenel et al. [34] | DLBCL | 21/M | Evans syndrome | None in 6 years prior | CHOP | 2 months | 3 | 0 month | Liver failure | Lamivudine | Yes |

| Yamagata et al. [35] | DLBCL | 55/M | None | None | CHOP | 6 months | 7 | 1 month | Liver failure | Lamivudine | Yes |

| Colson et al. [36] | DLBCL | 48/M | None | None | CHOP | 4 months | 4 | 1 month | Hepatitis | Entecavir | No |

| Garcia-Rodriguez et al. [21] | FL | 53/F | None | Yes (not stated- third-line therapy) | CHOP | 11 months | 3 | 9 months | Hepatitis | Lamivudine | No |

| Garcia-Rodriguez et al. [21] | DLBCL | 68/F | None | None | CHOP | 17 months | 6 | 12 months | Liver failure | Lamivudine | Yes |

| Miyagawa et al. [37] | DLBCL | 75/M | None | None | CHOP | 10 months | 6 | 6 months | Hepatitis | Lamivudine | No |

| Koo et al. [38] | MCL | 71/M | None | None | CHOP | 15 months | 9 | 0 | Liver failure | NR | NR |

| Northwestern active surveillance, 2007 | DLBCL | 61/M | Prior GIST | None | CHOP and radiation | 5 months | 6 | 1 month | Liver failure (warranting liver transplant) | Adefovir | No |

| Northwestern active surveillance, 2009 | DLCBL | 47/F | None | None | CHOP | 10 months | 6 | 0 months | Hepatitis | Tenofovir | No |

| Taiwan active surveillance, 2009 | DLBCL | 79/F | None | None | CHOP | 6 months | 6 | 2 months | Hepatitis | Telbivudine | No |

NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; FSGN, focal segmental glomerulonephritis; M, male; F, female; pts, patients; HBV, hepatitis B virus; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; CHEP, cyclophosphamide doxorubicin, etoposide, prednisone; CP, cyclophosphamide, prednisone; AZA, azathioprine; IFN, interferon; HDAC, high-dose cytarabine; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; NR, not reported; VCR, vincristine; Dex, dexamethasone.

Table 2.

HBV surface antigen positive rituximab-associated HBV reactivation: case reports

| Author | NHL type | Age/gender | Comorbidity | Received prophylaxis (lamivudine) | Prior immunosuppressive therapy | Concurrent immune suppressants | Time to reactivate from first rituximab | Doses of rituximab | Time to reactivate from last rituximab | Liver outcome | Treatment of reactivation (drug) | Death |

| Tsutsumi et al. [39] | DLBCL | 68/F | None | No | None | CHOP | 4 months | 3 | 3 months | Liver failure | Yes (lamivudine) | Yes |

| Dai et al. [20] | DLBCL | 21/M, 33/M, 41/F, 42/M | None | Yes (through 4 weeks after R-CHOP) | None | CHOP (all pts) | 8–12 months | 6 (all pts) | 4, 6, 6, and 8 months | Hepatitis | Yes (lamivudine—all) | None |

| Law et al. [40] | FL | 57/M | None | Yes | None | CHOP | 9 months | 6 | 5 months | Liver failure | Yes (tenofovir; lamivudine resistant) | Yes |

| Perceau et al. [23] | Cutan NHL | 78/F | None | No | CVP 6 years prior, CEP 2 year prior | None | 13 months | 4 | 12 months | Liver failure | Yes (lamivudine) | Yes |

| Kaled et al. [41] | WM | 32/F | None | No | None | Fludarabine | 9 months | 7 | 5 months | Hepatitis | Yes (lamivudine and adefovir) | No |

| Yang et al. [24] | FL | 41/F | None | No | Leukeran 1 year prior | None | 13 months | 4 | 12 months | Hepatitis | Yes (lamivudine) | No |

| Marino et al. [42] | DLBCL | 59/M | None | No | None | CHOP | 9 months | 8 | 3 months | Liver failure | Yes (lamivudine resistant) | Yes |

| Wasmuth et al. [43] | Indolent NHL | 55/M | None | No | None | Fludarabine based | 6 months | 6 | 2 months | Liver failure | Yes (lamivudine) | Yes |

| He et al. [22] | DLBCL | 29/F | None | Yes | None | Chemotherapy | 12 months | NR | 7 months | Hepatitis | Yes (lamivudine) | No |

| Dillon et al. [44] | DLBCL | 21/F | None | No | None | CHOP | 3 months | 4 | 0 months | Liver failure | Yes (lamivudine) | Yes |

| Aomatsu et al. [45] | DLBCL | 57/F | None | No | No | CHOP | 10 months | 6 | 5 months | Liver failure | Yes (lamivudine and plasma exchange) | Yes |

| Taiwan active surveillance, 2009 | SLL | 56/M | None | Yes (lamivudine) | R-CVP × 8 (1 year prior) and rituximab maintenance | No | 14 months | 10 | 1 month | Hepatitis | Yes (adefovir and entecavir; lamivudine resistant) | No |

NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; WM, Waldenstroms macroglobulinemia; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; M, male; F, female; Cutan, cutaneous; pts, patients; HBV Hepatitis B virus; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; R-CVP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide vincristine, prednisone; CEP, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, prednisone; NR, not reported.

The median number of rituximab doses received before HBV-R was 6 (range 3–10). The median time from last rituximab dose to HBV-R was 3 months (range 0–12), while HBV-R occurred at a median of 1 month (range 0–12) after the last dose of rituximab for HBcAb(+) patients compared with 5 months (range 0–12) for HBsAg(+) cases (P = 0.021). Of note, 29% of all HBV-Rs occurred ≥6 months after the last dose of rituximab [12.5% of HBcAb(+) versus 40% of HBsAg(+) cases]. Of the HBsAg(+) HBV-R group, 7 of 15 patients received prophylactic antiviral therapy (most commonly lamivudine); 5 of 7 HBV-Rs occurred after discontinuation of antiviral therapy. In terms of outcome, 55% of patients experienced fulminant liver failure (17 of 31), while the remaining had HBV-related hepatitis. Furthermore, 48% (15 of 31) of patients with rituximab-associated HBV-R died.

FDA MedWatch data

Over the same 12-year period, 118 cases of rituximab-associated HBV-R were submitted to the FDA AERS database that met our search criteria. The statistical signal in the AERS database was very strong for an association of HBV-R in lymphoproliferative patients treated with rituximab (PRR = 28.5, 95% CI 23.9–34.1, EBGM = 26.4, 95% CI 21.4–31.1). Sixty-eight percent of all cases were reported after 2004 with 31% being reported in the last 2 years. Further, 54% (64 of 118) of FDA HBV-R cases were reported from the United States, while the remaining cases were reported from outside the US. This compares to medical literature HBV-R cases, where only 9% (17 of 183) were from the United States (P < 0.002). Median age of FDA cases was 57.5 years (range 21–83) with a male-to-female ratio of 1.73. The case fatality rate among FDA AERS reports was 58.4%. Twenty-seven random FDA AERS cases, matched to year reported, were extracted and compared with literature case reports for data completeness. Comparison of completeness of source data of the literature case reports versus the FDA AERS reports is contained in Table 3. The literature cases were more complete with an overall completeness ratio for literature reports versus the FDA cases of 2.37 (P < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Completeness/quality of case reports: literature versus FDA MedWatch database

| Type of information | Literature case reports (n = 27) % reporting | FDA AERS cases (n = 27) % reporting | Completeness ratio | Pa |

| HBV statusb | 100 | 15 | 6.67 | <0.0001 |

| NHL subtype | 93 | 78 | 1.19 | 0.145 |

| Age and gender | 93 | 81 | 1.15 | 0.226 |

| Prior/current immunosuppressive therapy | 100 | 63 | 1.59 | 0.001 |

| Number of doses of rituximab received | 93 | 59 | 1.58 | 0.011 |

| Time from last dose of rituximab | 100 | 74 | 1.35 | 0.008 |

| Liver outcome | 96 | 52 | 1.85 | 0.001 |

| Treatment of reactivation | 89 | 19 | 4.68 | 0.000 |

| Survival | 96 | 89 | 1.08 | 0.312 |

| Overall completeness | 96 (232/242) | 59 (143/242) | 1.63 | <0.0001 |

Two-sided Fisher P value.

HBcAb(+) or HBsAg(+).

HBV, hepatitis B virus; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; AERS, Adverse Event Reporting System.

case series: meta-analysis of HBV reactivation

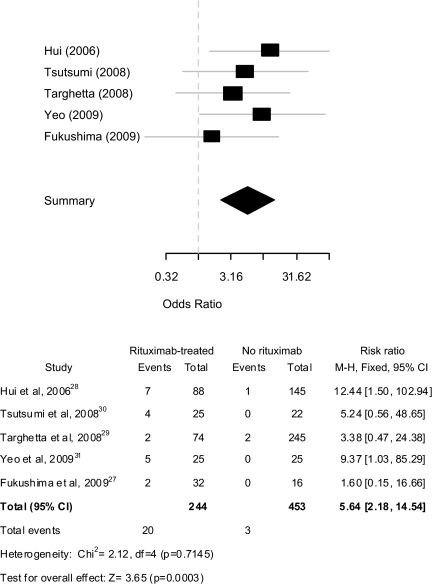

Of rituximab-associated HBV-R cases reported through case series (n = 156), 80 were HBcAb(+)/HBsAg(−) and 76 HBsAg(+) (Tables 4 and 5). Of all case series, five included a control group (i.e. treated with nonrituximab therapy) [46,48,49,51,53]; the series by Wang et al. [54] was not included as HBV-R was not adequately defined. The cumulative incidence of rituximab-associated HBV-R among these five series was significantly higher at 8.2% (20 of 244) compared with 0.6% (3 of 453) for the chemotherapy-alone group (P < 0.0001). The pooled effect of rituximab-based therapy on HBV-R remained significantly increased under a fixed effects model [odds ratio (OR) 5.64, 95% CI 2.18–14.54, P = 0.0003] with no evidence of heterogeneity between studies (Figure 1).

Table 4.

HBV core antibody positive (surface antigen negative) rituximab-associated HBV reactivation: case series

| Author | NHL type | Concurrent immune suppression | Incidence of rituximab-associated HBV reactivation (versus nonrituximab reactivation, if available) | Time from last rituximab and/or chemotherapy | Mortality rate (rituximab groups)a |

| Hui et al. [46] | Mixed NHL and HL (n = 233) | Rituximab/chemotherapy (n = 88); chemotherapy alone (n = 145) | 8.0% (7/88) with rituximab/chemotherapy (versus 0.1% (1/145) chemotherapy, P < 0.001)b | 8–28 weeks conversion to HBsAg(+), but 8–212 weeks HBV DNA (after last therapy)c | 43% |

| Li et al. [47] | DLBCL (n = 11) | CHOP | 45% (5/11) with HBV reactivation | NR | 40% |

| Targhetta et al. [48] | Mixed (n = 319) | Rituximab/chemotherapy (n = 74) and chemotherapy alone (n = 245) | 2.7% (2/74) with rituximab/chemotherapy (versus 0.8% (2/245) with chemotherapy, P < 0.05) | NR | 0 |

| Yeo et al. [49] | DLBCL (n = 46) | Rituximab/CHOP (n = 21); CHOP (n = 25) | 24% (5/21) with R-CHOP (versus 0/25 with CHOP, P < 0.0148) | 1–5 months | 20% |

| Hanbali et al. [50] | Mixed (n = 26) | Mixed (n = 26) | 27% (7/26) acute liver eventsd with rituximab-based therapy; 5/7 with liver failure | Median onset acute liver eventsd 6.2 months after rituximab (2 pts developed acute liver events at 21 and 36 months) | NR |

| Fukushima et al. [51] | Mixed (n = 48) | Mixed (n = 48) | 6% (2/32) who received rituximab with HBV reactivation (versus 0/16 without rituximab) | 8 months from last rituximab dose | 0 |

| Kusumoto et al. [52] | Mixed (n = 50) | None/rituximab alone (n = 2), R-CHOP (n = 40), R-chemotherapy without steroids (n = 4), ASCT (n = 3) | NR; 50 total pts with reactivation; 40% of pts with fulminant liver failure | NR | 50% |

Among pts with HBV reactivation.

Six of 49 pts receiving rituximab plus steroid-containing regimen versus 2/195 pts without rituximab plus steroid-containing regimen developed HBV-related hepatitis (12.2% versus 1.0%, respectively, P < 0.001); on multivariate analysis, rituximab plus steroid-containing regimen was the only independent factor associated with HBV-related hepatitis after chemotherapy (RR, 13.8; 95% CI 2.8–68.3; P < 0.001).

HBV DNA level preceded de novo HBV-related hepatitis by median 18.5 weeks.

Acute liver events were defined by acute elevation of liver enzymes, abnormal liver biopsy diagnostic of hepatitis or liver necrosis, hepatic encephalopathy, or demonstration of active viral DNA replication by PCR.

NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma; wks, weeks; pts, patients; HBV Hepatitis B virus; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; NR, not reported; RR, relative risk.

Table 5.

HBV surface antigen-positive rituximab-associated HBV reactivation: case series

| Author | NHL type | Received prophylaxis (lamivudine) | Concurrent immune suppressants | Incidence of rituximab-associated HBV reactivation (versus nonrituximab reactivation, if available) | Mortality |

| Tsutsumi et al. [53] | Mixed | 10/25 rituximab-based with prophylaxisa | Rituximab alone, rituximab/chemotherapy, chemotherapy alone (n = 47) | 20% (1/5) rituximab alone and 16% (3/20) rituximab/chemotherapy (versus 0/22 chemotherapy, P = 0.07) | NR |

| Wang et al. [54] | DLBCL | None | CHOP (n = 13) | 33% (13/40) rituximab/chemotherapy with hepatic dysfunction (versus 34% (14/41) chemotherapy) | NR |

| Hanbali et al. [50] | Mixed | None | Mixed (n = 6) | 65% (4/6) with acute liver eventsb and 30% (2/6) with liver failure | NR |

| Pei et al. [55] | Mixed | 5/15 received lamivudine | Mixed (n = 15) | 80% (12/15) with reactivationd | 17%c |

| Kusumoto et al. [52] | Mixed | NR | None/rituximab alone (n = 7), R-CHOP (n = 24), R-chemotherapy without steroids (n = 15) | NR (47 total pts with reactivation); 21% of pts with fulminant liver failure | 28% |

Zero of 10 HBV reactivation for pts with lamivudine prophylaxis versus 4/15 (27%) without antiviral prophylaxis.

Acute liver events defined by acute elevation of liver enzymes, abnormal liver biopsy diagnostic of hepatitis or liver necrosis, hepatic encephalopathy, or demonstration of active viral DNA replication by PCR.

One of 4 that received prophylaxis died versus 1/8 without prophylaxis.

dFour of 5 (80%) that received lamivudine with HBV reactivation versus 8/10 (80%) without prophylaxis with HBV reactivation.

NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; HBV Hepatitis B virus; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone; NR, not reported.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of case series assessing the risk of HBV reactivation in lymphoma patients treated with rituximab-based therapy compared with nonrituximab controls.

Since only one of the five series in the meta-analysis contained a HBsAg(+)-related series [53], it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions among this patient group regarding the added risk that rituximab contributes to reactivation. If only the four HBcAb(+) case series are included in the meta-analysis [46,48, 49,51], the OR remained highly significant at 5.73 (95% CI 2.01–16.33; Z = 3.33, P = 0.0009) without heterogeneity (χ2 = 2.12, P = 0.5473). It should also be noted, that the incidence and mortality rates of rituximab-associated HBV-R varied considerably across all case series. Among all HBcAb(+) case series, the incidence of HBV-R ranged from 2.7% to 45%, while the associated mortality rates varied from 0% to 50% (Table 4). For HBsAg(+) cases, the rate of HBV-R ranged from 16% to 80% (Table 5).

antiviral prophylaxis data

Among HBsAg(+) case series, data regarding the effectiveness of prophylactic antiviral medications in rituximab-treated patients was mixed. Tsutsumi et al. [53] showed that 0 of 10 rituximab-treated patients who received antiviral prophylaxis had HBV-R, while 4 of 15 (27%) without lamivudine prophylaxis experienced HBV-R. However, we recently reported that use of prophylactic lamivudine did not decrease the risk of HBV-R with a rate of reactivation of 80% among rituximab-based treated patients regardless of use of antiviral prophylaxis (Table 5) [55]. In our case series, we noted two episodes of breakthrough HBV-related hepatitis associated with lamivudine-resistant tyrosine–methionine–aspartate–aspartate HBV mutants.

discussion

Through a comprehensive literature review and meta-analysis, we attempted to characterize the scope of rituximab-associated HBV-R. The vast majority of rituximab-related clinical trials have excluded patients with history of HBV exposure; thus, the extent of rituximab-associated HBV-R data is primarily from the medical literature and through reports to the FDA MedWatch system. Over a 12-year period, 183 cases of rituximab-associated HBV-R were reported through the medical literature and 118 cases to the FDA. From literature case reports, 55% of patients experienced liver failure, while the associated mortality rate was 48%. In addition, from case series that had an associated nonrituximab-treated control group, a significant increase in rituximab-associated HBV-R was documented. In interpreting these observations, several factors should be considered.

Increasing evidence has linked rituximab to viral infections including herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and JC virus [15, 56]. In February 2006, the rituximab label was changed to include information for NHL patients who developed serious viral infections after rituximab treatment [57]. However, the incidences and characteristics of these infections, including risk factors, remain to be elucidated. In addition, the pathophysiology of rituximab-induced viral infections is unclear. The mechanism underlying HBV-R following rituximab treatment is likely more complex than simple B-cell depletion. B-lymphocytes may stimulate cellular immune responses, both to auto-antigens and foreign antigens [58]. Further, Stasi et al. [59] demonstrated following rituximab treatment that significant changes occur in T-lymphocyte activity, including increased Th1/Th2 and Tc1/Tc2 ratios, increased expression of Fas ligand on Th1 and Th2 cells, and expansion of oligoclonal T cells. A role for the importance of B-lymphocytes in HBV-R may also be in part related to reduction of anti-HBV antibodies (i.e. HBsAb+) caused by rituximab and the associated host immunity balance. Tsutsumi et al. [39] showed that despite serum immunoglobulin levels remaining constant through treatment, anti-HBV surface antibody titers significantly decreased with rituximab therapy.

In our data, we found that among HBcAb(+) cases series with an associated nonrituximab-treated control group, there was a more than fivefold higher rate of HBV-R for patients who received rituximab-based therapy. It should also be noted that only one HBV case series was prospective; in that study, Yeo et al. [49] found a HBV-R rate of 25% among HBcAb(+) lymphoma patients, who received rituximab-combination chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) compared with 0 for CHOP. Given the retrospective nature of most reports and the wide range of HBV-R (3%–45%), it is difficult to make firm recommendations for HBcAb(+) patients. However, in the United States and Europe, it is becoming standard practice to administer antiviral prophylaxis for this patient population [60], although continued prospective studies are needed to clearly delineate the benefit of this strategy.

Controlled data regarding the risk of single-agent rituximab-induced HBV-R in HBsAg(+) or the added risk of rituximab to chemotherapy in this patient population are sparse. Only one of the available five HBsAg(+) case series included a control group treated without rituximab; in that study, Tsutsumi et al. [53] showed that 16% of patients treated with rituximab alone or rituximab/chemotherapy experienced HBV-R compared with 0 patients who received chemotherapy alone. In chemotherapy-related HBsAg(+) studies, the antiviral agent lamivudine has been associated with a significant reduction in chemotherapy-associated HBV-R-related mortality to <5% to 10% compared with 60% to 70% without prophylaxis [9, 11]. Tsutsumi et al. [53] found that 0 of 10 HBsAg(+) rituximab-treated patients given lamivudine had HBV-R compared with 4 of 15 rituximab-treated patients not given prophylaxis. However, we recently reported that prophylactic lamivudine did not decrease the risk of HBV-R in rituximab-treated HBsAg(+) patients, although total patient numbers were small (n = 15) [61]; however, of the four of five HBsAb(+) patients treated with rituximab-based therapy without prophylaxis who experienced HBV reactivation, three of the four occurred after withdrawal of antiviral prophylaxis (duration of prophylaxis: median 2 months after last rituximab dose). An important consideration is the optimal length of antiviral prophylaxis. Several groups advocate continuation of antiviral therapy for at least 6 months following the last cycle of chemotherapy and longer after rituximab [62]. Although with extended use of antiviral therapy, lamivudine resistance is a growing area of concern (up to 30%–35%) [40,42,45,63]. Newer, more potent antivirals with much lower rates of HBV resistance, such as adefovir and tenofovir, should be examined.

It was interesting that over the same period where 183 unique cases were published in peer-reviewed medical literature, only 118 cases were reported to the FDA. Of note, all serious adverse events (such as HBV-R) that occur in United States, as well as ex-United States, are required to be reported to the FDA. FDA AERS is a passive surveillance system with associated limitations including underreporting, reporting bias, and data completeness. Indeed, we found that cases published in the medical literature were highly superior in data quality compared with FDA reports. Case reports in the FDA database need to be interpreted cautiously as not all cases are systemically validated. Furthermore, the FDA AERS data do not provide true incidence or prevalence information due to lack of information of number of patients exposed. This limits analyses to validated data mining signal detection techniques [27–29]. Nevertheless, it should be acknowledged that the FDA AERS system is worldwide in its scope for drugs approved in the United States and it often provides important safety signals.

Some limitations of our analysis should be noted. The number of HBV-R occurrences depicted here are likely an underestimation of the true incidence. It is difficult to accurately estimate the incidence of rituximab-associated HBV-R among persons with NHL in part due to incomplete reporting of reactivation cases among rituximab-treated patients and incomplete data on the number of unique patients with lymphoid malignancies who have received rituximab. On the other hand, HBV-R cases with morbid/fatal complications are more likely to be reported. Additionally, an interpretation has been that HBV-R occurs mostly in endemic HBV areas (e.g. Hong Kong and Taiwan) [55, 64, 65]. Rates are not as high, but recent data from urban USA centers show that ∼10% of all cancer patients treated with immunosuppressive therapy have past or active HBV infection [66, 67]. The retrospective nature of the majority of rituximab-associated HBV-R cases also makes definitive conclusions difficult regarding incidence and mortality. However, given the results of the meta-analysis and the fact that nearly one-third of HBV-R in case reports occurred >6 months after the last rituximab dose, which is an unusual occurrence with chemotherapy alone, supports the likelihood of a real effect of rituximab-mediated HBV-R. ‘Delayed’ HBV-R (i.e. >6 months) may in part be explained by the long half-life of rituximab, whereby serum levels (and B-cell suppression) may be detected in patients for >6 months [68], while other factors may also be involved (e.g. immunoglobulins and T-cell immunity).

In conclusion, rituximab therapy may increase the risk of developing HBV-R and associated liver failure and death in HBcAb(+) and HBsAg(+) patient populations. As rituximab continues to gain more indications of use (including non-malignant indications) and newer monoclonal CD20 antibodies become clinically available (e.g. ofatumumab), it is important that clinicians and patients be aware of the potential for HBV-R. In the absence of prospective data, it is advisable that patients with HBV infection [HBsAg(+) or HBcAb(+)], who receive rituximab-based therapy receive concomitant antiviral prophylaxis and for at least 9 months after the last rituximab dose. It is critical, however, that prospective studies of antibody-induced HBV-R continue as many unanswered questions remain (i.e. risk of HBV-R with single-agent rituximab; the ideal type, length, and benefit of antiviral prophylaxis, especially in HBsAg(+) populations; identification of additional risk factors (e.g. co-infection with hepatitis C, D, and/or E viruses [69, 70]); and mechanisms of rituximab-associated HBV-R). Finally, increased efforts should be given toward post-marketing drug surveillance and the timely dissemination of data to practicing physicians.

disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted in part through the the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports (RADAR) Project.

funding

National Cancer Institute (K23 CA109613-A1).

References

- 1.Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733–1745. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis B in Europe and worldwide. J Hepatol. 2003;39(Suppl 1):S64–S69. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng AL, Hsiung CA, Su IJ, et al. Steroid-free chemotherapy decreases risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation in HBV-carriers with lymphoma. Hepatology. 2003;37:1320–1328. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Markovic S, Drozina G, Vovk M, Fidler-Jenko M. Reactivation of hepatitis B but not hepatitis C in patients with malignant lymphoma and immunosuppressive therapy. A prospective study in 305 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:2925–2930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang R, Lau GK, Kwong YL. Chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation for cancer patients who are also chronic hepatitis B carriers: a review of the problem. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:394–398. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lok AS, Liang RH, Chiu EK, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus replication in patients receiving cytotoxic therapy. Report of a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:182–188. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90599-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, et al. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol. 2000;62:299–307. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200011)62:3<299::aid-jmv1>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee GW, Ryu MH, Lee JL, et al. The prophylactic use of lamivudine can maintain dose-intensity of adriamycin in hepatitis-B surface antigen (HBs Ag)-positive patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma who receive cytotoxic chemotherapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2003;18:849–854. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.6.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loomba R, Rowley A, Wesley R, et al. Systematic review: the effect of preventive lamivudine on hepatitis B reactivation during chemotherapy. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:519–528. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-7-200804010-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li YH, He YF, Jiang WQ, et al. Lamivudine prophylaxis reduces the incidence and severity of hepatitis in hepatitis B virus carriers who receive chemotherapy for lymphoma. Cancer. 2006;106:1320–1325. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziakas PD, Karsaliakos P, Mylonakis E. Effect of prophylactic lamivudine for chemotherapy-associated hepatitis B reactivation in lymphoma: a meta-analysis of published clinical trials and a decision tree addressing prolonged prophylaxis and maintenance. Haematologica. 2009;94:998–1005. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.005819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeo W, Chan PK, Ho WM, et al. Lamivudine for the prevention of hepatitis B virus reactivation in hepatitis B s-antigen seropositive cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:927–934. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumagai K, Takagi T, Nakamura S, et al. Hepatitis B virus carriers in the treatment of malignant lymphoma: an epidemiological study in Japan. Ann Oncol. 1997;8(Suppl 1):107–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeo W, Johnson PJ. Diagnosis, prevention and management of hepatitis B virus reactivation during anticancer therapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:209–220. doi: 10.1002/hep.21051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aksoy S, Harputluoglu H, Kilickap S, et al. Rituximab-related viral infections in lymphoma patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:1307–1312. doi: 10.1080/10428190701411441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Westhoff TH, Jochimsen F, Schmittel A, et al. Fatal hepatitis B virus reactivation by an escape mutant following rituximab therapy. Blood. 2003;102:1930. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Czuczman MS, Grillo-Lopez AJ, White CA, et al. Treatment of patients with low-grade B-cell lymphoma with the combination of chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and CHOP chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:268–276. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dervite I, Hober D, Morel P. Acute hepatitis B in a patient with antibodies to hepatitis B surface antigen who was receiving rituximab. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:68–69. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. http://www.fda.gov/Safety/MedWatch/SafetyInformation/SafetyAlertsforHumanMedicalProducts/ucm166521.htm (14 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dai MS, Chao TY, Kao WY, et al. Delayed hepatitis B virus reactivation after cessation of preemptive lamivudine in lymphoma patients treated with rituximab plus CHOP. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:769–774. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0899-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Rodriguez MJ, Canales MA, Hernandez-Maraver D, Hernandez-Navarro F. Late reactivation of resolved hepatitis B virus infection: an increasing complication post rituximab-based regimens treatment? Am J Hematol. 2008;83:673–675. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He YF, Li YH, Wang FH, et al. The effectiveness of lamivudine in preventing hepatitis B viral reactivation in rituximab-containing regimen for lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:481–485. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0454-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perceau G, Diris N, Estines O, et al. Late lethal hepatitis B virus reactivation after rituximab treatment of low-grade cutaneous B-cell lymphoma. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1053–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang SH, Kuo SH. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus during rituximab treatment of a patient with follicular lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:325–327. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0396-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovric S, Erdbruegger U, Kumpers P, et al. Rituximab as rescue therapy in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a single-centre experience with 15 patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:179–185. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gossmann J, Scheuermann EH, Kachel HG, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B two years after rituximab therapy in a renal transplant patient with recurrent focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a note of caution. Clin Transplant. 2009;23:431–434. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2008.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bate A, Evans SJ. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:427–436. doi: 10.1002/pds.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baker RA, Pikalov A, Tran QV, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and diabetes mellitus in the US Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Database: a systematic Bayesian Signal Detection Analysis. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2009;42:11–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lehman HP, Chen J, Gould AL, et al. An evaluation of computer-aided disproportionality analysis for post-marketing signal detection. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007;82:173–180. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niscola P, Del Principe MI, Maurillo L, et al. Fulminant B hepatitis in a surface antigen-negative patient with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia after rituximab therapy. Leukemia. 2005;19:1840–1841. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sarrecchia C, Cappelli A, Aiello P. HBV reactivation with fatal fulminating hepatitis during rituximab treatment in a subject negative for HBsAg and positive for HBsAb and HBcAb. J Infect Chemother. 2005;11:189–191. doi: 10.1007/s10156-005-0385-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Law JK, Ho JK, Hoskins PJ, et al. Fatal reactivation of hepatitis B post-chemotherapy for lymphoma in a hepatitis B surface antigen-negative, hepatitis B core antibody-positive patient: potential implications for future prophylaxis recommendations. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1085–1089. doi: 10.1080/10428190500062932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sera T, Hiasa Y, Michitaka K, et al. Anti-HBs-positive liver failure due to hepatitis B virus reactivation induced by rituximab. Intern Med. 2006;45:721–724. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozgonenel B, Moonka D, Savasan S. Fulminant hepatitis B following rituximab therapy in a patient with Evans syndrome and large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2006;81:302. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamagata M, Murohisa T, Tsuchida K, et al. Fulminant B hepatitis in a surface antigen and hepatitis B DNA-negative patient with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma after CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48:431–433. doi: 10.1080/10428190601059704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colson P, Borentain P, Coso D, et al. Entecavir as a first-line treatment for HBV reactivation following polychemotherapy for lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:148–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyagawa M, Minami M, Fujii K, et al. Molecular characterization of a variant virus that caused de novo hepatitis B without elevation of hepatitis B surface antigen after chemotherapy with rituximab. J Med Virol. 2008;80:2069–2078. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koo YX, Tan DS, Tan IB, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in a patient with resolved hepatitis B virus infection receiving maintenance rituximab for malignant B-cell lymphoma. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:655–656. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsutsumi Y, Tanaka J, Kawamura T, et al. Possible efficacy of lamivudine treatment to prevent hepatitis B virus reactivation due to rituximab therapy in a patient with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:58–60. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0748-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Law JK, Ali JA, Harrigan PR, et al. Fatal postlymphoma chemotherapy hepatitis B reactivation secondary to the emergence of a YMDD mutant strain with lamivudine resistance in a noncirrhotic patient. Am J Hematol. 2006;81:969–972. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khaled Y, Hanbali A. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in a case of Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia treated with chemotherapy and rituximab despite adefovir prophylaxis. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:688. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marino D, Boso C, Crivellari G, et al. Fatal HBV-related liver failure during lamivudine therapy in a patient with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Tumori. 2008;94:748–749. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wasmuth JC, Fischer HP, Sauerbruch T, Dumoulin FL. Fatal acute liver failure due to reactivation of hepatitis B following treatment with fludarabine/cyclophosphamide/rituximab for low grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Eur J Med Res. 2008;13:483–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dillon R, Hirschfield GM, Allison ME, Rege KP. Fatal reactivation of hepatitis B after chemotherapy for lymphoma. BMJ. 2008;337:a423. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.680498.BE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aomatsu T, Komatsu H, Yoden A, et al. Fulminant hepatitis B and acute hepatitis B due to intrafamilial transmission of HBV after chemotherapy for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in an HBV carrier. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:167–171. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-1000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hui CK, Cheung WW, Zhang HY, et al. Kinetics and risk of de novo hepatitis B infection in HBsAg-negative patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:59–68. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li JM, Wang L, Shen Y, et al. Rituximab in combination with CHOP chemotherapy for the treatment of diffuse large B cell lymphoma in Chinese patients. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:639–645. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Targhetta C, Cabras MG, Mamusa AM, et al. Hepatitis B virus-related liver disease in isolated anti-hepatitis B-core positive lymphoma patients receiving chemo- or chemo-immune therapy. Haematologica. 2008;93:951–952. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NW, et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:605–611. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanbali A, Khaled Y. Incidence of hepatitis B reactivation following Rituximab therapy. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:195. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fukushima N, Mizuta T, Tanaka M, et al. Retrospective and prospective studies of hepatitis B virus reactivation in malignant lymphoma with occult HBV carrier. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:2013–2017. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kusumoto S, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Ueda R. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus following systemic chemotherapy for malignant lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2009;90:13–23. doi: 10.1007/s12185-009-0359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsutsumi Y, Shigematsu A, Hashino S, et al. Analysis of reactivation of hepatitis B virus in the treatment of B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in Hokkaido. Ann Hematol. 2009;88:375–377. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0585-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang F, Xu RH, Luo HY, et al. Clinical and prognostic analysis of hepatitis B virus infection in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:115. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shih LN, Sheu JC, Wang JT, et al. Serum hepatitis B virus DNA in healthy HBsAg-negative Chinese adults evaluated by polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol. 1990;32:257–260. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890320412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carson KR, Evens AM, Richey EA, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy after rituximab therapy in HIV-negative patients: a report of 57 cases from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports project. Blood. 2009;113:4834–4840. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-186999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2006/ucm108810.htm (14 August 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bouaziz JD, Yanaba K, Venturi GM, et al. Therapeutic B cell depletion impairs adaptive and autoreactive CD4+ T cell activation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20878–20883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709205105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stasi R, Del Poeta G, Stipa E, et al. Response to B-cell depleting therapy with rituximab reverts the abnormalities of T-cell subsets in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood. 2007;110:2924–2930. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marzano A, Angelucci E, Andreone P, et al. Prophylaxis and treatment of hepatitis B in immunocompromised patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pei SN, Chen CH, Lee CM, et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus following rituximab-based regimens: a serious complication in both HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative patients. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:255–262. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0806-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lubel JS, Testro AG, Angus PW. Hepatitis B virus reactivation following immunosuppressive therapy: guidelines for prevention and management. Intern Med J. 2007;37:705–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schnepf N, Sellier P, Bendenoun M, et al. Reactivation of lamivudine-resistant occult hepatitis B in an HIV-infected patient undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy. J Clin Virol. 2007;39:48–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hui CK, Sun J, Au WY, et al. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in hematopoietic stem cell donors in a hepatitis B virus endemic area. J Hepatol. 2005;42:813–819. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang JT, Wang TH, Sheu JC, et al. Detection of hepatitis B virus DNA by polymerase chain reaction in plasma of volunteer blood donors negative for hepatitis B surface antigen. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:397–399. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ludwig E, Mendelsohn RB, Taur Y, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis B core antibody in a population initiating immunosuppressive therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;28 9008a. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hwang J, Fisch M, Zhang H, et al. Hepatitis. B screening and positivity prior to chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28 9009a. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gordan LN, Grow WB, Pusateri A, et al. Phase II trial of individualized rituximab dosing for patients with CD20-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1096–1102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hsieh CY, Huang HH, Lin CY, et al. Rituximab-induced hepatitis C virus reactivation after spontaneous remission in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2584–2586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ollier L, Tieulie N, Sanderson F, et al. Chronic hepatitis after hepatitis E virus infection in a patient with non-Hodgkin lymphoma taking rituximab. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:430–431. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-6-200903170-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]