Abstract

Background: The phase III EXTREME study demonstrated that combining cetuximab with platinum/5-fluorouracil (5-FU) significantly improved overall survival in the first-line treatment of patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (R/M SCCHN) compared with platinum/5-FU alone. The aim of this investigation was to evaluate elevated tumor EGFR gene copy number as a predictive biomarker in EXTREME study patients.

Patients and methods: Dual-color FISH was used to determine absolute and relative EGFR copy number. Models of differing stringencies were used to score and investigate whether increased copy number was predictive for the activity of cetuximab plus platinum/5-FU.

Results: Tumors from 312 of 442 patients (71%) were evaluable by FISH and met the criteria for statistical analysis. A moderate increase in EGFR copy number was common, with high-level amplification of the gene occurring in a small fraction of tumors (∼11%). Considering each of the models tested, no association of EGFR copy number with overall survival, progression-free survival or best overall response was found for patients treated with cetuximab plus platinum/5-FU.

Conclusion: Tumor EGFR copy number is not a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of cetuximab plus platinum/5-FU as first-line therapy for patients with R/M SCCHN.

Keywords: cetuximab, copy number, EFGR, EXTREME, FISH, platinum/5-fluorouracil

introduction

The randomized phase III EXTREME study demonstrated that the addition of cetuximab to platinum/5-fluorouracil (5-FU) chemotherapy statistically significantly improved overall survival when given as first-line treatment to patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (R/M SCCHN) compared with platinum/5-FU alone (median 10.1 versus 7.4 months, hazard ratio 0.80, P = 0.04) [1]. The addition of cetuximab to platinum/5-FU also led to significant improvements in progression-free survival (PFS) and best overall response rate, which was approximately doubled. Safety analysis demonstrated that the combination was feasible, with a manageable side-effect profile. The 2.7-month median survival time benefit associated with the addition of this epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted monoclonal antibody to standard platinum-based chemotherapy represents the most significant advance in the treatment of the disease in this setting for ∼30 years. These data complement an earlier study in locally advanced SCCHN which showed that the addition of cetuximab to radiotherapy conferred a long-term survival benefit compared with radiotherapy alone, the magnitude of which (9% absolute survival benefit at 5 years) was similar to that achievable in this setting with chemoradiotherapy [2–5].

Recent studies have shown that the clinical impact of EGFR-targeted therapies can be increased if treatment administration can be tailored to particular subpopulations of patients whose tumors have specific molecular alterations [6, 7]. Elevated gene copy number, which may arise within a tumor cell as the result of an increase in the numbers of chromosomes encoding the gene (polysomy) or may occur as a consequence of local amplification of a chromosomal region (gene amplification), is a somatic event with potential predictive utility. Increased copy number may indicate that a tumor is highly dependent on the activity of an amplified gene for continued proliferation and/or survival, a situation described as oncogene addiction [8]. In this case, the tumor may be particularly sensitive to anticancer agents that target the product of that gene and elevated copy number may consequently be a predictive biomarker, as exemplified by ERBB2 gene amplification in breast cancer and sensitivity to trastuzumab [9]. Copy number can be evaluated in tumors and the two different causal genetic mechanisms can be distinguished through the use of dual-color FISH analysis incorporating a gene-specific probe combined with a centromere-specific probe for the chromosome encoding that gene.

The data on the impact of EGFR gene copy number status on cetuximab efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is contradictory. While some studies reported an association of high EGFR gene copy number and improved outcome in mCRC and NSCLC patients receiving cetuximab [10–14], other studies failed to identify similar associations [15–17]. No data on EGFR gene copy number and cetuximab efficacy have so far been reported for SCCHN.

Expressed in 90%–100% of tumors, up-regulation of EGFR appears to be an early marker of SCCHN carcinogenesis [18–20], and high-level tumor expression has been correlated with poor clinical outcome [21]. Elevation of EGFR copy number is a characteristic somatic event that occurs in the development of this disease and may additionally be an indicator of poor prognosis [22, 23]. The aim of the current study was to investigate in the large relatively homogeneous population recruited for the randomized phase III EXTREME study whether elevated tumor EGFR copy number was predictive for the activity of cetuximab plus platinum/5-FU, administered as first-line therapy to patients with R/M SCCHN.

patients and methods

EXTREME study design

As previously reported [1], inclusion criteria included age ≥18 years, untreated R/M SCCHN, ineligibility for local therapy, Karnofsky Performance Score of ≥70% and adequate organ function. Patients were excluded if they had received prior surgery or radiotherapy within 4 weeks of study entry or prior systemic chemotherapy (apart from for locally advanced disease).

Patients were randomly assigned to receive every 3 weeks for up to six cycles either cisplatin, 100 mg/m2 day 1, or carboplatin area under the curve of 5 day 1 (physician’s choice); plus 5-FU infused at 1000 mg/m2/day for 4 days either with or without cetuximab, administered at an initial dose of 400 mg/m2 and then 250 mg/m2 weekly, both during chemotherapy and subsequently as maintenance therapy until the occurrence of disease progression or unacceptable toxicity. The primary end point was overall survival. Secondary end points included PFS, best overall response, disease control, time-to-treatment failure, duration of response and safety.

collection and storage of patient material

All patients provided written informed consent for EGFR testing on tumor samples. All available formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue specimens from patients in the clinical study (blocks and slides) were analyzed at a central laboratory (Wuppertal Institute of Pathology, Wuppertal, Germany) according to a standard protocol.

FISH analysis

FISH analysis was carried out on deparaffinized 3- to 5-μm FFPE sections using the prepared solutions and protocol provided in the Histology FISH Accessory Kit (Dako, Denmark; see supplemental Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online). EGFR copy number was assessed using an EGFR/CEN-7 FISH probe mix (Dako). Fluorescence was visualized using a DM50000 B (Leica, Germany) fluorescence microscope with a DAPI filter and a Texas Red double filter. EGFR (normal location 7p11.2) signals appeared red and CEN-7 signals (probe homologous to the centromeric region of chromosome 7) appeared green.

statistical methods

The FISH investigation was a retrospectively planned exploratory analysis. For a patient to be included, a target of 100 evaluable (where a signal was present for both EGFR and CEN-7) cells and a minimum of 50 cells were to be assessed. Patients from the intention-to-treat (ITT) population with FISH assessments for at least 50 cells formed the FISH ITT population. For each analyzed cell, observed EGFR/CEN-7 signals were used to determine absolute and relative EGFR copy numbers. Average (mean) signal counts or ratios per patient were calculated.

Given the possibility that the most appropriate scoring system to assess the association of copy number changes and clinical outcome may vary according to the disease or the particular stage of disease, a series of different systems were used to define FISH-positive (elevated EGFR copy number) and FISH-negative (nonelevated EGFR copy number) status in R/M SCCHN, including five predefined EGFR enrichment models and the Colorado scoring system, previously developed for the analysis of EGFR copy number in NSCLC (Table 1) [12, 24].

Table 1.

FISH scoring systems

| Scoring systems and models | Definitions |

| EGFR enrichment model for evaluation of FISH status | |

| Model A | |

| FISH positive | EGFR/CEN-7 ratio ≥2 or presence of EGFR signal cluster |

| Model B | |

| FISH positive | EGFR signal count ≥3 or presence of EGFR signal cluster |

| Model C | |

| FISH positive | EGFR signal count ≥6 or presence of EGFR signal cluster |

| Model D | |

| FISH positive | EGFR/CEN-7 ratio ≥2 or presence of EGFR signal cluster or EGFR signal count ≥3 |

| Model E | |

| FISH positive | EGFR/CEN-7 ratio ≥2 or presence of EGFR signal cluster or EGFR signal count ≥6 |

| Colorado scoring system | |

| FISH positive | ≥40% of cells display ≥4 EGFR counts or the presence of gene amplification, as defined by either |

| Mean EGFR/CEN-7 ratio ≥2 | |

| >10% of cells displaying >15 EGFR counts | |

| >10% of the cells displaying the presence of loose or tight EGFR signal clusters or atypically large EGFR signals (EGFR cluster scored) | |

CEN-7, probe for centromeric region of human chromosome 7.

EGFR enrichment models

EGFR enrichment models were evaluated in both treatment groups of the study. Five different models were developed using different thresholds to define each analyzed cell as FISH positive or negative. To derive a factor representative of the degree of heterogeneity across the tumor cells sampled for each patient, the percentage of FISH-positive tumor cells (of those analyzed) was then calculated for each patient and model (FISH score; ranging from 0% to 100%). For each model, for patients in each study arm, these values were used to construct scatter plots of survival time and PFS time versus the FISH score. These plots were subsequently assessed both visually and statistically (see supplemental Methods, available at Annals of Oncology online) in an attempt to identify a particular threshold value that allowed for a significant enrichment of patients with a survival benefit according to EGFR copy number status. For each model, for each arm, box plots of best overall response according to FISH score were also constructed and assessed visually to determine whether a clear correlation was apparent between tumor response and EGFR copy number.

Colorado scoring system

EGFR copy number was also defined for patients in each study arm according to the previously established Colorado scoring system (Table 1). This system differed from the enrichment models in that it allowed the classification of tumors (rather than individual tumor cells) as either FISH positive or negative. The association of FISH status according to the Colorado system with clinical outcome was investigated using log-rank (PFS and overall survival) and Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (response) tests.

results

patient population and material

Tumor tissue samples were available from 381 of the 442 (86%) patients in the ITT population of the EXTREME study. Samples from 312 patients (71%) were evaluable by FISH and met the criteria for statistical analysis (FISH ITT population; Table 2). Treatment arms were essentially balanced with respect to the number of evaluable samples, with 158 deriving from patients receiving cetuximab plus chemotherapy (71%) and 154 from those receiving chemotherapy alone (70%). The effects of treatment in relation to overall survival, PFS and best overall response were comparable for the ITT and FISH ITT populations (see supplemental Table 1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 2.

ITT patients assessed for EGFR tumor gene copy number by FISH

| Patients, n (%) | Cetuximab + chemotherapy | Chemotherapy alone |

| Randomly assigned to treatment (ITT population) | 222 (100) | 220 (100) |

| FISH assessments not performed | 28 (13) | 33 (15) |

| FISH assessments performed | 194 (87) | 187 (85) |

| FISH results not availablea | 35 (16) | 33 (15) |

| Assessment not possible for technical reasons | 29 (13) | 23 (10) |

| Excluded from statistical analysis (sample taken after first dose of cetuximab) | 11 (5) | 12 (5) |

| FISH results available | 159 (72) | 154 (70) |

| FISH results available for ≥50 cells (FISH ITT population) | 158 (71) | 154 (70) |

| FISH results for <50 cells | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

Both reasons may apply.

ITT, intention to treat.

FISH analysis

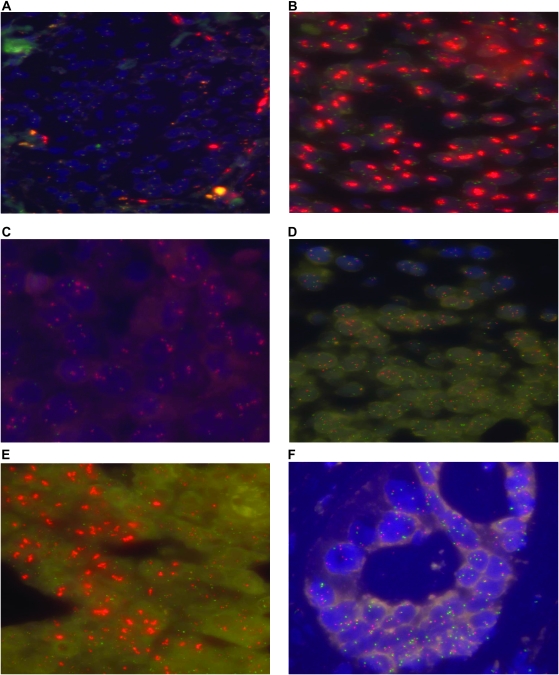

Dual-color FISH analysis was carried out to evaluate for each tumor the number of signals in each cell related to EGFR and to the centromeric region of chromosome 7. Representative images from these assays are shown in Figure 1. The average numbers of EGFR and CEN-7 signals and the average ratio of EGFR/CEN-7 signals were calculated for the tumors of patients in each arm and in the overall FISH ITT population (Table 3). The decimal fraction of cells with EGFR signal clusters was also determined.

Figure 1.

Representative FISH analyses showing tumors comprising cells with (A) normal gene copy number (two signals for each probe per cell); (B) high-level EGFR gene amplification, as demonstrated by the presence of large EGFR signal clusters; (C) low/moderate-level gene amplification, as demonstrated by the presence of small EGFR signal clusters; (D) polysomy, as demonstrated by >2 EGFR/CEN-7 signals per cell; (E) heterogeneity for EGFR copy number, with only a subpopulation showing high-level gene amplification and (F) heterogeneity for EGFR copy number, with certain cells showing polysomy and others, normal copy numbers.

Table 3.

Average signal counts following FISH analysis (FISH ITT population)

| FISH evaluations | Cetuximab + chemotherapy, n = 158 | Chemotherapy alone, n = 154 | FISH ITT population, n = 312 |

| CEN-7 | |||

| Average numbers of signals/cell, n | |||

| Median of all patients (range) | 2.3 (1.1–6.2) | 2.4 (1.2–5.8) | 2.3 (1.1–6.2) |

| Mean of all patients (SD) | 2.5 (0.88) | 2.5 (0.82) | 2.5 (0.85) |

| Patients in categories defined by average number of signals/cell, n (%) | |||

| 1–2 | 61 (39) | 50 (32) | 111 (36) |

| >2–3 | 57 (36) | 61 (40) | 118 (38) |

| >3–4 | 33 (21) | 33 (21) | 66 (21) |

| >4 | 7 (4) | 10 (6) | 17 (5) |

| EGFR | |||

| Average numbers of signals/cell, n | |||

| Median of all patients (range) | 2.6 (1.1–26.8) | 2.8 (1.0–43.2) | 2.7 (1.0–43.2) |

| Mean of all patients (SD) | 3.4 (3.26) | 4.1 (4.77) | 3.7 (4.08) |

| Patients in categories defined by average number of signals/cell, n (%) | |||

| 1–2 | 48 (30) | 40 (26) | 88 (28) |

| >2–3 | 50 (32) | 49 (32) | 99 (32) |

| >3–4 | 36 (23) | 35 (23) | 71 (23) |

| >4–5 | 9 (6) | 10 (6) | 19 (6) |

| >5 | 15 (9) | 20 (13) | 35 (11) |

| EGFR/CEN-7 ratio | |||

| Average signal ratio/cell | |||

| Median of all patients (range) | 1.0 (0.6–10.7) | 1.1 (0.5–20.8) | 1.1 (0.5–20.8) |

| Mean of all patients (SD) | 1.5 (1.57) | 1.9 (2.57) | 1.7 (2.13) |

| Patients in categories defined by average signal ratio/cell, n (%) | |||

| 0–1 | 24 (15) | 17 (11) | 41 (13) |

| >1–2 | 119 (75) | 116 (75) | 235 (75) |

| >2 | 15 (9) | 21 (14) | 36 (12) |

| EGFR signal clusters | |||

| Decimal fraction of cells per patient with EGFR signal cluster present | |||

| Median of all patients (range)a | 0 (0–1.0) | 0 (0–1.0) | 0 (0–1.0) |

| Mean of all patients (SD) | 0.1 (0.24) | 0.1 (0.30) | 0.1 (0.27) |

| Patients in categories defined by decimal fraction of cells with clustersb, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 139 (88) | 132 (86) | 271 (87) |

| >0 to <0.25 | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 8 (3) |

| 0.25–0.75 | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 8 (3) |

| >0.75 to <1 | 8 (5) | 9 (6) | 17 (5) |

| 1 | 1 (0.6) | 7 (5) | 8 (3) |

0 = no cluster in any cell; 1 = clusters in every cell.

For example, 0.25 equates to 25% of cells having clusters.

CEN-7, probe for centromeric region of human chromosome 7; ITT, intention to treat; SD, standard deviation.

The distributions of the average signal counts for EGFR and CEN-7 and the EGFR/CEN-7 ratio were comparable between the two treatment groups. Tumor EGFR gene copy number was elevated in a substantial fraction of patients, with 40% of the FISH ITT population having average EGFR signal counts per cell of >3 and 11% of >5 (Table 3). The observed elevation of tumor EGFR gene copy number was due to both polysomy events (27% of patients had average CEN-7 signal counts of >3) and local amplification (12% of patients had an average cellular EGFR/CEN-7 ratio of >2). In 13% of patients, a fraction of tumor cells was scored as having strong localized EGFR amplification, such that individual signals could not be distinguished (clusters): 11% of patients had such clusters in ≥25% of tumor cells (Table 3).

As there was no known EGFR copy number threshold value that might be of predictive utility in this setting, a series of models with different stringencies were designed to provide definitions, which could be used to assign FISH status (Table 1). These models were then used to assess whether elevated EGFR copy number, as defined in each model, was predictive for cetuximab efficacy.

EGFR enrichment models

For each evaluable tumor, a FISH score was determined according to one of the five different enrichment models (Table 1). The distribution of FISH scores was comparable between subgroups of tumor samples from the invasive front and tumor center (data not shown). As expected, the median FISH score in models A, C and E which used more stringent criteria for defining a FISH-positive cell was markedly lower than in models B and D, which used less stringent criteria (supplemental Figure 1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

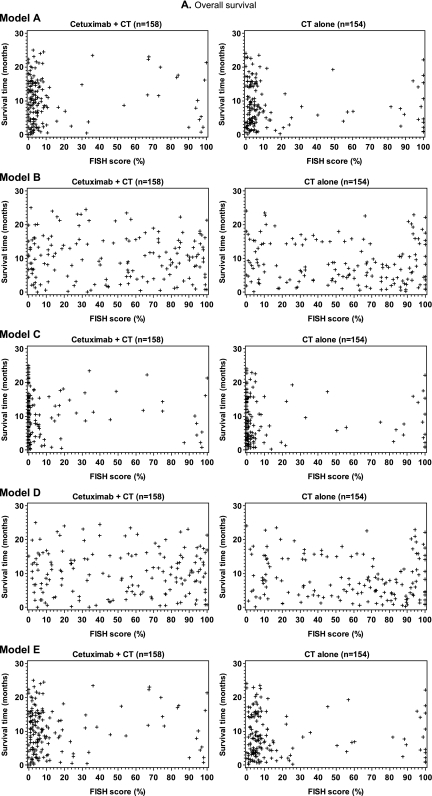

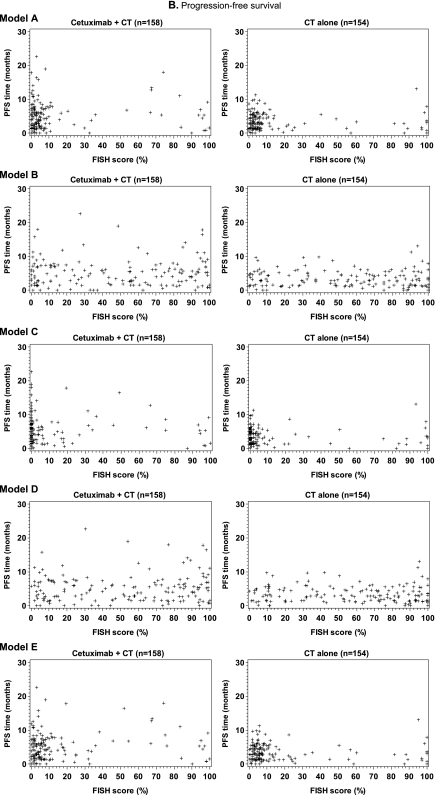

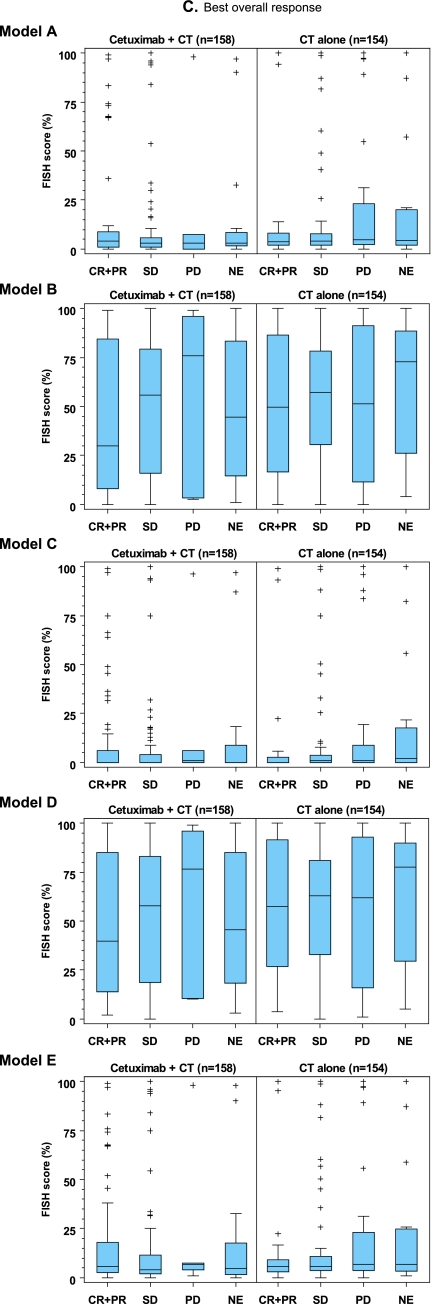

In an initial exploration of the predictive potential of EGFR FISH status, scatter plots were constructed for each model for survival time versus the respective FISH score for patients in both study arms (Figure 2A). These plots did not demonstrate a visible correlation between EGFR FISH score and survival time for any model, in either study arm. The process was repeated for each model for the analysis of PFS time versus the respective FISH score for patients in both study arms (Figure 2B), with similar results. Evaluation of the misclassification error rates further supported the lack of predictive utility of EGFR FISH status in relation to overall survival and PFS (see supplemental Results, available at Annals of Oncology online). Box plots of FISH score versus best overall response for each model were also constructed. As for the other efficacy end points, these plots did not show a visible correlation between parameters (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Scatter and box plots did not demonstrate an association between FISH score and (A) overall survival time, (B) progression-free survival (PFS) time or (C) best overall response, for patients in either study arm, when EGFR copy number was analyzed according to enrichment models A–E, as indicated. The upper and lower boundaries of each box plot represent the 25th and 75th percentile and the horizontal lines within the box represent the median values. The bars extend to the last observation not defined as an extreme value (represented by + symbols) or to the minimum/maximum values if an extreme value was not identified. CR, complete response; CT, chemotherapy; NE, not evaluable; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Colorado model

The Colorado model (Table 1) was used to define tumor EGFR FISH status for patients in both study arms. Treatment outcome was then assessed according to FISH status. Using this scoring system, 32% of patients were deemed to have EGFR FISH-positive tumors. No significant association was apparent for this model between elevated EGFR copy number and overall survival, PFS or best overall response (Table 4).

Table 4.

Colorado FISH status according to tumor site and efficacy according to FISH status (FISH ITT population)

| Parameter | Cetuximab + chemotherapy |

Chemotherapy alone |

||

| FISH+, n = 50 | FISH−, n = 108 | FISH+, n = 51 | FISH−, n = 103 | |

| Overall survival time | ||||

| Median, months | 10.5 | 10.6 | 7.2 | 7.8 |

| Hazard ratioa (95% CI) | 1.02 (0.69–1.51) | 1.04 (0.71–1.51) | ||

| P value | 0.93 | 0.86 | ||

| PFS time | ||||

| Median, months | 6.2 | 5.7 | 3.1 | 4.1 |

| Hazard ratioa (95% CI) | 0.86 (0.58–1.27) | 1.05 (0.71–1.54) | ||

| P value | 0.46 | 0.81 | ||

| Best overall response rate, % | 36.0 | 34.3 | 11.8 | 22.3 |

| Odds ratiob (95% CI) | 1.08 (0.54–2.18) | 0.46 (0.18–1.22) | ||

| P value | 0.83 | 0.12 | ||

Hazard ratios <1 correspond to benefit for FISH+ patients.

Odds ratios >1 correspond to benefit for FISH+ patients.

CI, confidence interval; PFS, progression-free survival.

discussion

The collection of tissue samples during the course of large randomized studies in different settings provides a powerful platform to assess the predictive potential of candidate biomarkers, with the analysis of the control arm allowing discrimination between effects, which are prognostic for standard treatment or predictive for the experimental therapy [25]. Evaluation in such individual studies is important as particular mutational or epimutational events which may occur across various tumor types can have different phenotypic consequences in different cell types or against a background of other disease-typical genetic lesions. Consequently, the same mutational event may be predictive for a treatment agent in one tumor type and not another. This has been exemplified in the case of cetuximab by the contrasting data from randomized studies in advanced colorectal cancer and advanced NSCLC, where KRAS codon 12/13 mutations are predictive for treatment benefit for cetuximab plus standard chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone in the former setting [26, 27] but not the latter [16, 17]. The consequence of such findings is that the potential utility of predictive biomarkers cannot be assumed to be generalizable for a given agent and must be assessed specifically in each tumor type and in each treatment setting. In relation to SCCHN, KRAS is mutated (at least in the above-mentioned codons) in only a small fraction of cases [28–30], and therefore, KRAS status is not likely to be a useful predictive marker for cetuximab benefit in this disease.

The current study, the largest of its type in this setting, which included an extensive series of tumor samples from 312 patients, represents a truly comprehensive analysis investigating the influence of a disease-relevant candidate biomarker, EGFR copy number status, on clinical outcome in patients with R/M SCCHN treated with cetuximab plus platinum-based chemotherapy as part of a large randomized phase III study. As the first such exploratory analysis, an appropriate threshold for abnormal copy number on which this and future similar studies could be based had to be determined. By using different enrichment models and calculating a FISH score for each tumor, a broad spectrum of thresholds (from moderate to high) was tested. In addition to these models, the Colorado scoring system, which has been used to demonstrate the predictive utility of EGFR gene copy number in NSCLC [12], was also evaluated for its predictive potential in this setting.

Considering each of these models covering a range of stringencies, no association of EGFR copy number status with overall survival, PFS and best overall response was found. Given the extensive nature of this analysis, it seems reasonable to conclude that EGFR copy number status as determined by FISH is not a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of cetuximab combined with platinum/5-FU in the first-line treatment of R/M SCCHN. Although there was a trend for a higher response rate in patients receiving chemotherapy alone with EGFR FISH-negative compared with FISH-positive tumors, according to the Colorado scoring system, no robust association between EGFR copy number status and any efficacy measure was detected in the overall study population (data not shown). Thus, EGFR copy number status does not appear to be a prognostic marker in this setting.

High EGFR copy number was previously found to be a marker of poor prognosis in a FISH analysis of a heterogeneous population of 82 patients with SCCHN, 75 of whom were assessable for FISH [22]. Seventy-two primary tumor blocks were initially available from patients who had received no prior anticancer treatment and 14 from patients with recurrent tumors (four paired samples). All patients in the survival analysis were treated with curative intent. The difference between this and the current study in relation to the assessment of the prognostic potential of EGFR copy number may be due to the dissimilarity of the patient populations analyzed (R/M SCCHN in the current study versus potentially curable stages I–IV patients in the previous study). Analyzed tissues in the current study were essentially therefore derived from patients with more advanced disease who were to receive palliative treatment. In this context, we cannot derive a definitive conclusion with respect to patients who might be treated with curative intent with cetuximab since it could well be that EGFR copy number has prognostic and/or predictive utility in this setting.

In relation to the mean signal counts, 40% of tumors had EGFR copy numbers of >3 and 11% of tumors had copy numbers of >5. The tumor EGFR/CEN-7 ratio was >2 for 12% of patients and 11% of patients had EGFR signal clusters in ≥25% of their tumor cells. Applying the Colorado system, 32% of tumors were scored as EGFR FISH positive. Taken together, these data indicate that a moderate increase in EGFR copy number is a common event in SCCHN, with high-level amplification of the gene occurring in a small fraction of tumors (∼11%).

The EGFR copy number data in the current study are in the range of values reported from earlier FISH analyses [22, 23, 31, 32]. Two smaller studies using the Colorado scoring system found incidences of FISH-positive tumors of 57% (43 of 75 patients) [22] and 13% (4 of 31 patients) [31], respectively. Analyzing a large series of SCCHN samples using a tissue microarray, Freier et al. [32] reported that 13% (63 of 496) of tumors had 10% of cells showing ≥8 signals or tight signal clusters from the gene-specific probe, which is comparable to the incidence of high-level EGFR amplification reported in this study. However, it should be noted that even among patients in the current study whose tumors had high-level increases in EGFR gene copy number based on the more stringent enhancement models, no clear distinction in relation to survival benefit was observed (Figure 2A).

In summary, the retrospective analysis of tissue collected during the randomized phase III EXTREME study has indicated that tumor EGFR copy number status is not a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of cetuximab plus platinum/5-FU administered as first-line therapy to patients with R/M SCCHN. Therefore, analyzing EGFR copy number by FISH in this setting before the administration of cetuximab does not appear to provide any clinically relevant information for the physician. This study has therefore shown that the benefit conferred by the addition of cetuximab to standard chemotherapy for this disease is independent of tumor EGFR copy number.

funding

Merck KGaA.

disclosure

LL reports a compensated consultancy/advisory role with Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Merck Serono and Amgen, has received research funding from Eisai Pharmaceuticals, Exelixis, Lilly, Merck Serono and Amgen and travel funds from Merck Serono. RM is a member of a speakers’ bureau for Merck Serono. FR has conducted research sponsored by Merck Serono. AK reports receiving occasional honoraria for sponsored lectures from Merck Serono and sanofi-aventis. CS is a full time employee of Merck KGaA, as is SS, who also holds stock in the company. JBV has served on advisory boards of Merck Serono and has received honoraria for lectures from Merck Serono. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The excellent technical support (FISH analysis) of Mrs. Sylvia Vogel and Mrs. Petra Boehmer is highly appreciated. We would like to thank all EXTREME study investigators who provided patient tissue samples for analysis. The authors acknowledge the contribution of Jim Heighway, who provided medical writing services on behalf of Merck KGaA.

References

- 1.Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer: 5-year survival data from a phase 3 randomised trial, and relation between cetuximab-induced rash and survival. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:21–28. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70311-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budach V, Stuschke M, Budach W, et al. Hyperfractionated accelerated chemoradiation with concurrent fluorouracil-mitomycin is more effective than dose-escalated hyperfractionated accelerated radiation therapy alone in locally advanced head and neck cancer: final results of the radiotherapy cooperative clinical trials group of the German Cancer Society 95-06 Prospective Randomized Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1125–1135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denis F, Garaud P, Bardet E, et al. Final results of the 94-01 French Head and Neck Oncology and Radiotherapy Group randomized trial comparing radiotherapy alone with concomitant radiochemotherapy in advanced-stage oropharynx carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:69–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semrau R, Mueller RP, Stuetzer H, et al. Efficacy of intensified hyperfractionated and accelerated radiotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy with carboplatin and 5-fluorouracil: updated results of a randomized multicentric trial in advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:1308–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linardou H, Dahabreh IJ, Bafaloukos D, et al. Somatic EGFR mutations and efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in NSCLC. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:352–366. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linardou H, Dahabreh IJ, Kanaloupiti D, et al. Assessment of somatic k-RAS mutations as a mechanism associated with resistance to EGFR-targeted agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and metastatic colorectal cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:962–972. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein IB, Joe A. Oncogene addiction. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3077–3080. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3293. discussion 3080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauter G, Lee J, Bartlett JM, et al. Guidelines for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing: biologic and methodologic considerations. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1323–1333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cappuzzo F, Finocchiaro G, Rossi E, et al. EGFR FISH assay predicts for response to cetuximab in chemotherapy refractory colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:717–723. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frattini M, Saletti P, Romagnani E, et al. PTEN loss of expression predicts cetuximab efficacy in metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1139–1145. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsch FR, Herbst RS, Olsen C, et al. Increased EGFR gene copy number detected by fluorescent in situ hybridization predicts outcome in non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with cetuximab and chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3351–3357. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lievre A, Bachet JB, Le Corre D, et al. KRAS mutation status is predictive of response to cetuximab therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3992–3995. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Personeni N, Fieuws S, Piessevaux H, et al. Clinical usefulness of EGFR gene copy number as a predictive marker in colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab: a fluorescent in situ hybridization study. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5869–5876. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Italiano A, Follana P, Caroli FX, et al. Cetuximab shows activity in colorectal cancer patients with tumors for which FISH analysis does not detect an increase in EGFR gene copy number. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:649–654. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khambata-Ford S, Harbison CT, Hart LL, et al. Analysis of potential predictive markers of cetuximab benefit in BMS099, a phase III study of cetuximab and first-line taxane/carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:918–927. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O'Byrne KJ, Bondarenko I, Barrios C, et al. Molecular and clinical predictors of outcome for cetuximab in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): data from the FLEX study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27 (Suppl; Abstr 8007) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christensen ME, Therkildsen MH, Hansen BL, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression on oral mucosa dysplastic epithelia and squamous cell carcinomas. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1992;249:243–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00714485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grandis JR, Tweardy DJ. Elevated levels of transforming growth factor alpha and epidermal growth factor receptor messenger RNA are early markers of carcinogenesis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3579–3584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grandis JR, Melhem MF, Barnes EL, Tweardy DJ. Quantitative immunohistochemical analysis of transforming growth factor-alpha and epidermal growth factor receptor in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer. 1996;78:1284–1292. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960915)78:6<1284::AID-CNCR17>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholson RI, Gee JM, Harper ME. EGFR and cancer prognosis. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(Suppl 4):S9–S15. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung CH, Ely K, McGavran L, et al. Increased epidermal growth factor receptor gene copy number is associated with poor prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4170–4176. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Temam S, Kawaguchi H, El-Naggar AK, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor copy number alterations correlate with poor clinical outcome in patients with head and neck squamous cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2164–2170. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varella-Garcia M. Stratification of non-small cell lung cancer patients for therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: the EGFR fluorescence in situ hybridization assay. Diagn Pathol. 2006;1:19. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-1-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandrekar SJ, Sargent DJ. Clinical trial designs for predictive biomarker validation: theoretical considerations and practical challenges. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4027–4034. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bokemeyer C, Bondarenko I, Makhson A, et al. Fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin with and without cetuximab in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:663–671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Cutsem E, Kohne CH, Hitre E, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408–1417. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yarbrough WG, Shores C, Witsell DL, et al. ras mutations and expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1337–1347. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson JA, Irish JC, Ngan BY. Prevalence of RAS oncogene mutation in head and neck carcinomas. J Otolaryngol. 1992;21:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lea IA, Jackson MA, Li X, et al. Genetic pathways and mutation profiles of human cancers: site- and exposure-specific patterns. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1851–1858. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agulnik M, da Cunha Santos G, Hedley D, et al. Predictive and pharmacodynamic biomarker studies in tumor and skin tissue samples of patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck treated with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2184–2190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.6554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freier K, Joos S, Flechtenmacher C, et al. Tissue microarray analysis reveals site-specific prevalence of oncogene amplifications in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:1179–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.