Abstract

Background

Epidemiological investigations, detections and vaccines of hepatitis E (HE) have been paid a focus of attention in prior studies, while studies on clinical features and risk factors with a large number of sporadic HE patients are scarce.

Results

Sporadic HE can occur throughout the year, with the highest incidence rate in the first quarter of a year, in central of China. Of the 210 patients, 85.2% were male, and the most common clinical symptoms were jaundice (85.7%), fatigue (70.5%) and anorexia (64.8%). Total bilirubin (TBil), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and international normalized ratio (INR) were found as major risk factors for death of HE patients. There was an overall mortality of 10%, and the mortality in the cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic group was 25% and 6.47%, respectively. Moreover, hepatitis E virus (HEV) infected patients with liver cirrhosis had a higher mortality and incidence of complications.

Conclusions

TBil, BUN, and INR are major risk factors of mortality for HE. Liver cirrhosis can aggravate HE, and lead to a higher mortality. HEV infection can cause decompensation in patients with cirrhosis, as evidenced by a worsening Child-Pugh score.

1. Background

HE caused by HEV infection is transmitted by the fecal-oral route and generally causes an acute self-limiting illness followed by complete recovery, which is the same as hepatitis A (HA). However, the mortality of HE is higher than HA and hepatitis B (HB), especially in pregnant women (with a mortality of 20%~30%)[1]. HE is endemic in many developing countries with poor sanitation and insufficient public-health infrastructures. Nevertheless, HEV infections are reported even in developed countries in recent years, making the disease a great threat to human health. For example, a recent study reported that a seroprevalence of HEV was found among 20% of blood donors in USA and an evidence of HEV epidemic was found in Japan[2]. HEV infections have also been documented in Australia and European Union[3-6]. Besides, cases of sporadic HE in people without histories of recent travels have been reported in developed regions.

The incidence of HE is higher and higher, while mortalities in different areas are distinct. A study in India revealed that the mortality of out-break of HE was 0.07%-0.6%[7]. The mortality of in-hospital patients with acute HE had a mortality of 1%~3%[1]. Till now, most studies were focused on the epidemiological investigation, detections and vaccines, while studies on clinical features and risk factors of death for HE with a large number of patients are lacking. There are studies on the outcome of HEV infection in patients with chronic liver disease from India, Nepal, France and the UK[8-11]. It was showed that the mortality of HEV in patients with cirrhosis was 70% at 1 year[8]. However, similar reports from China are scarce.

2. Methods

2.1 Patients

This study included 210 in-hospital HE patients from Department of Infectious Disease of Wuhan Tongji Hospital from January 2007 to December 2008. HE case definition: alanine aminotransferase, ALT ≧ 2.5 × upper limits of normal (ULN) and HEV IgM positive, or a rising HEV IgG or HEV PCR positive[11]. Cirrhotic patients with sepsis, primary liver cancer, surgical obstructive jaundice, hepatorenal syndrome and those consuming alcoholic during previous 6 months were excluded from the study. The cirrhosis groups were matched for Child-Pugh score twice: the first time was 1 month before admission and the second was after admission. Each patient after discharge from the hospital was followed up 4 weekly at least for 6 months.

2.2 Methods

2.2.1 Pathogenic Detection

Sera from each patient was tested for HEV-IgM, HEV-IgG, HAV-IgM, anti-HCV, HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb, HBAb using commercial ELISA kit ( Beijing Wantai Company).

2.2.2 Reverse transcription and nested PCR for HEV[12]

HEV RNA was extracted and precipitated from 200 μl of serum samples by acid-guanidinium-phenol method (Trizol LS Reagent Invitrogen, USA). Reverse primer E5: 5'CTACACGAAACCGARAGW (R = A or G, W = A or C) was used to reverse transcription. With primer E1 (5'CTGTTTAAYCTTGCTGACAC 3'(Y = C or T)) and primer E5, the first round of amplification was completed (94℃ pre-degeneration for 5 min, 94℃ for 40s, 53℃ for 40s, 72℃ for 40s, followed by 35 cycles, 72℃ for 10 min). The amplified material was used for the second-round nested amplification with primers E2 (5'GACAGAATTGATTTCGTCG 3') and E4 (5'GTCCTAATACTRTTGGTTGT3' (R = A or G)). The length of PCR product corresponding to ORF2 sequence was 189 bp (6298nt-6486nt).

2.2.3 Biochemical Tests

An automatic biochemical analyzer (Beckman L220) was used to analyze biochemical parameters, such as ALT, BUN, TBil, INR, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), albumin (ALB), total cholesterol (Tchol), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatinine (Cr), prothrombin activity (PTA).

2.2.4 Diagnosis of cirrhosis

Forty of 210 patients were diagnosed with liver cirrhosis before HEV infection, which was established by conventional clinical, biochemical, imaging, and endoscopic criteria[8]. The etiology of cirrhosis in patients was HB 20, Schistosomiasis 7, alcohol 3, hepatitis C 1, autoimmune hepatitis 1, alcohol plus HB 5, HB plus Schistosomiasis 1, Schistosomiasis plus alcohol 1, and HB plus Schistosomiasis and alcohol 1 case.

2.2.5 Statistics

Quantitative variables were expressed as means (± SD) and compared by the Student t-test, or represented as median (25th percentile-75th percentile). Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare serum biochemical indicators and χ2 or Fisher's exact test was used to enumeration data. Odds ratio (OR) for all variables was calculated by univariate and multivariate logistic regression. All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS software 13.0.

3. Results

3.1 Etiology Detected Results

Among 210 patients, 125 were diagnosed being infected with HEV alone, 1 co-infected with hepatitis A virus (HAV), and 75 co-infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV), 2 with hepatitis C virus (HCV), 3 with cytomegalovirus (CMV), 3 with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), 1 with CMV + EBV. Forty of the 210 patients had liver cirrhosis as well. Seventy-eight patients had detectable HEV RNA in their sera. All of them were genotype 4 which were confirmed by bidirectional sequencing and phylogenetic.

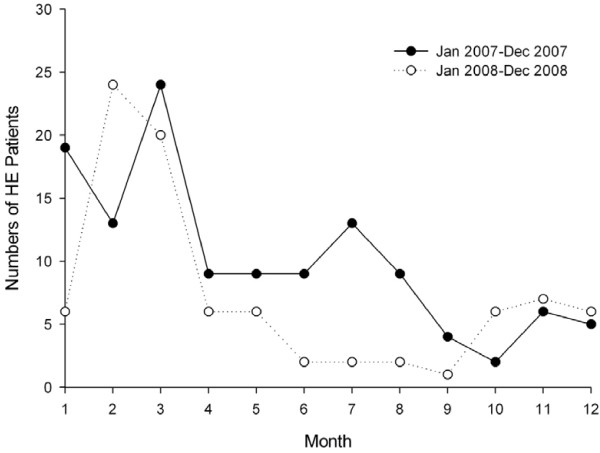

3.2 The Incidence Rate of HE in Different Seasons

It was found that 122 and 88 patients were infected with HE in 2007 and 2008, respectively. Although patients could be infected throughout a year, the incidence rate of HE was highest in the first quarter (from January to March) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The incidence of HE infection in different months of the year.

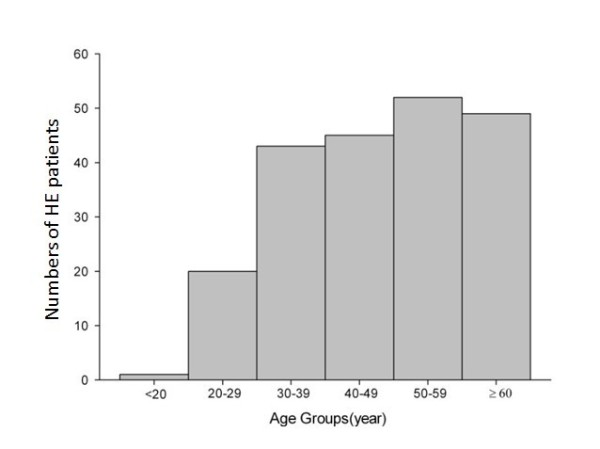

3.3 The Distribution of HE patients' Gender and Age

Of the 210 patients, 179 cases were male (85.2%) and 31 cases were female (14.8%). The ratio of male to female was approximately 5.8:1. Ages of the patients ranged from 17 to 92 years old (48.7 ± 14.9). There was only 1 case under 20 years old (0.5%), 90% of the patients were over 30 years of age (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Number of HE patients according to age group.

3.4 Clinical Symptoms and Serum Biochemistry

Jaundice, fatigue and anorexia were the most common clinical symptoms, with incidence rates of 85.7% (180/210), 70.5% (148/210), and 64.7% (136/210), respectively. Other less common symptoms were also observed, including abdominal distention (55/210, 26.2%), nausea (23/210, 11.0%), vomiting (14/210, 6.7%) and fever (16/210. 7.6%).

All patients were followed up for six months. Twenty-one patients died during this period, for a mortality of 10% (95% CI: 6.63%-14.80%). The main causes of death were upper gastrointestinal bleeding (6/21), hepatorenal syndrome (12/21), and hepatic encephalopathy(3/21). The results of clinical features and serum biochemistry were summarized in Table 1. Patients with old ages and liver cirrhosis were more likely to die than others. The level of TBil, Tchol, LDH, PTA and INR were significantly different between died patients and survivors. BUN and Cr, which reflect the renal function, were higher in the deceased group than in the survivor group.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical and biochemical parameters between the deceased group and the survival group

| Variable | Deceased group | Survival group | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 21 | 189 | - |

| Age in years | 59.67 ± 13.99 | 47.22 ± 13.97 | 0.0002 |

| Gender(male/female) | 20/1 | 159/30 | NS |

| ALT(U/L) | 731.00(202.00-1910.50) | 1070.50(381.00-1773.00) | NS |

| AST(U/L) | 659.00(228.10-1386.00) | 551.00(189.00-1242.25) | NS |

| GGT(U/L) | 62.00(44.00-115.50) | 131.00(73.00-221.00) | 0.007 |

| TBil(μmol/L) | 551.40(409.35-607.95) | 163.81(69.83-275.90) | < 0.001 |

| ALB(g/L) | 29.60(26.40-31.30) | 34.15(31.15-37.78) | < 0.001 |

| ALP(U/L) | 199.00(144.50-241.50) | 170.00(131.00-218.00) | NS |

| Tchol(mmol/L) | 1.33(0.98-1.86) | 3.23(2.51-3.92) | < 0.001 |

| LDH(U/L) | 274.00(223.00-385.00) | 200.00(151.00-261.00) | 0.001 |

| CHE(U/L) | 2941.00(2060.00-4269.50) | 4454.50(3021.25-5808.75) | 0.003 |

| BUN(mmol/L) | 14.50(6.07-24.51) | 4.44(3.64-5.61) | < 0.001 |

| Cr(μmol/L) | 124.05(70.83-253.55) | 64.00(55.38-73.78) | < 0.001 |

| PTA(%) | 46.00(32.00-70.00) | 92,50(71.00-112.75) | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.66(1.35-2.19) | 1.14(1.05-1.30) | < 0.001 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; TBil, total bilirubin; ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; Tchol, total cholesterol; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CHE, cholinesterase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; PTA, prothrombin activity; INR, international normalized ratio; and NS, not significant.

From table 2 we can see that age (OR = 1.067), TBil (OR = 1.010), ALB (OR = 0.781), Tchol (OR = 0.164), LDH (OR = 1.007), BUN (OR = 1.299), Cr (OR = 1.010), PTA (OR = 0.956), and INR (OR = 6.113) were the death risk factors of HE. Multivariate analysis of death risk factors in patients with HE were shown in Table 3. TBil, BUN, and INR were major risk factors

Table 2.

Risk factors of mortality among patients with HE by Univariate analysis

| Variable | Categories | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Continuous | 1.067 | 1.029--1.106 | 0.0005 |

| Gender | Female | 1 | ||

| Male | 4.173 | 0.538--32.343 | NS | |

| ALT | Continuous | 1.000 | 0.999-1.000 | NS |

| AST | Continuous | 1.000 | 1.000-1.000 | NS |

| GGT | Continuous | 1.000 | 0.997-1.002 | NS |

| TBil | Continuous | 1.010 | 1.006-1.013 | < 0.001 |

| ALB | Continuous | 0.781 | 0.696-0.877 | < 0.001 |

| ALP | Continuous | 1.001 | 0.999-1.003 | NS |

| Tchol | Continuous | 0.164 | 0.079-0.340 | < 0.001 |

| LDH | Continuous | 1.007 | 1.003-1.011 | 0.001 |

| CHE | Continuous | 1.000 | 0.999-1.000 | 0.005 |

| BUN | Continuous | 1.299 | 1.149-1.469 | 0.001 |

| Cr | Continuous | 1.010 | 1.003-1.016 | 0.003 |

| PTA | Continuous | 0.956 | 0.937-0.975 | < 0.001 |

| INR | Continuous | 6.113 | 2.401-15.561 | < 0.001 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT,γ-glutamyltransferase; TBil, total bilirubin; ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; Tchol, total cholesterol; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CHE, cholinesterase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; PTA, prothrombin activity; INR, international normalized ratio; and NS, not significant.

Table 3.

Risk factors of mortality among patients with HE by Multivariate analysis

| Variables | Categories | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBil | Continuous | 1.0009 | 1.004-1.014 | < 0.001 |

| BUN | Continuous | 1.178 | 1.034-1.341 | 0.014 |

| INR | Continuous | 9.216 | 1.969-43.129 | 0.005 |

TBil, total bilirubin; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; INR, international normalized ratio.

3.5 The Influence of Liver Cirrhosis on the Prognosis of Hepatitis E

Compared with hepatitis E infection patients without liver cirrhosis, the mortality of those with liver cirrhosis was increased (25% vs.6.47%, P = 0.002). The incidence of hepatic encephalopathy (6/40 vs. 8/170, p = 0.03), hepatorenal syndrome (8/40 vs. 5/170, P < 0.001) and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (24/40 vs. 14/170, P < 0.001) were higher than HEV infected patients without cirrhosis. The difference of ALT, GGT, ALB, Tchol, PTA, INR, BUN between two groups was significant as well (table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of demographic, biochemical parameters as well as Complications and mortality frequencies among patients infected with genotype 4 HEV with and without liver cirrhosis

| Parameter | HEV | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| with cirrhosis | Without cirrhosis | ||

| Number of patients | 40 | 170 | - |

| Age in years | 51.78 ± 14.70 | 48.02 ± 14.55 | NS |

| Gender(male/female) | 36/4 | 143/27 | NS |

| Mortality | 10(25%) | 11(6.47%) | 0.002 |

| Complications | |||

| Spontaneous peritonitis | 24(60%) | 14(8.24%) | < 0.001 |

| Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 2(5%) | 4(2.35%) | NS |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 8(20%) | 5(2.94%) | < 0.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 6(15%) | 8(4.71%) | 0.03 |

| ALT(U/L) | 574.5(150.25-1612.25) | 1158(478.75-1816.75) | 0.02 |

| AST(U/L) | 310.5(117-1198.5) | 670.5(208-1265.2) | NS |

| GGT(U/L) | 85(52.5-114.75) | 131(67-229) | 0.002 |

| TBil(umol/L) | 242.6(115.6-530.3) | 197.93(82.6-298.85) | NS |

| ALB(g/L) | 31(27.65-32.98) | 34.1(31.58-37.8) | < 0.001 |

| Tchol(mmol/L) | 2.17(1.71-3.27) | 3.18(2.45-3.9) | < 0.001 |

| CHE(U/L) | 3014.5(2125.75-3967) | 4356(3039.25-5752.25) | 0.001 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.5(4-9.29) | 4.65(3.64-6) | 0.032 |

| Cr(umol/L) | 64.9(55.35-116.6) | 65.5(56.2-78.8) | NS |

| PTA(%) | 63(42-85) | 93(72.95-113.5) | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.41(1.19-1.75) | 1.13(1.04-1.29) | < 0.001 |

HEV, hepatitisE virus; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GGT, γ-glutamyltransferase; TBil, total bilirubin; ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; Tchol, total cholesterol; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CHE, cholinesterase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; PTA, prothrombin activity; INR, international normalized ratio; and NS, not significant

The 40 HE patients with cirrhosis were assessed by Child-Pugh's score on the basis of reviewing their history, clinical symptoms and laboratory data one month ago. And this was before presenting HEV infection. Thirty-two cases (80%) were at the Child-Pugh stage A, 7 cases (17.5%) at the Child-Pugh stage B, and 1 case (2.5%) at the Child-Pugh stage C, with a mean score of 5.85 ± 1.29. After being in hospital, 4 cases (10%) were at stage A, 21 cases (52.5%) at stage B, and 15 cases (37.5%) at stage C, with a mean score of 8.83 ± 1.97. Child-Pugh's score of the patients after being in hospital was significantly worse than the patients before HEV infection (5.85 ± 1.29 vs. 8.83 ± 1.97, P < 0.001).

4. Discussion

There are four genotypes of HEV, but only one serotype. Genotypes 1 and 2 exclusively infect humans, whereas genotypes 3 and 4 can also infect other animals, particularly pigs. Genotype 4 has been proven the dominant genotype in China since the year of 2000[13-16]. In this study, seventy eight (37.14%) of 210 patients had detectable HEV RNA in their sera. All patients in whom HEV RNA was isolated were infected with genotype 4, which was congruent with those from China.

Contaminated drinking water has been served as sources of several outbreaks of HE in India[17-19]. It demonstrates that the contaminated water is one important reason for outbreak of HE, therefore outbreaks of HE were found in rainy or floodwater seasons. However, in contrast with the outbreak of HE, our data illustrated that the sporadic HE infection could occur throughout a year, and exhibited obvious seasonal occurrence. The incidence of HE in the first quarter of 2007 and 2008 were much higher than that in other quarters. HE is a zoonotic disease. The strongest evidence of zoonotic transmission of HE is from Japan[20,21]. Similarly, more meat in central of China is consumed in the first quarter of a year, since people in China celebrate their most important traditional festivals (the Spring Festival and the Lantern Festival) in the first quarter. So, this may be a possible reason for the seasonal occurrence. Another reason is that the weather in central of China in the first quarter is conducive to virus multiplication and propagation.

Although HEV and HAV are similar viruses in terms of the transmission mode and clinical manifestation, 90% of the HE patients were over 30 years of age, and we saw only one case under age 20 in this study, which are rather different from the HA patients. The reason for the difference of the age distribution is could be that HEV has a much lower secondary attack rate among exposed household members compared with the stable HAV (with a secondary attack rate of 20%-50%) [22,23].

Another noticeable feature of HE is that the male patients were much more than the female patients (5.8:1). The result is in accordance with other reports. For example, a nationwide survey of the prevalence of IgG anti-HEV in qualified blood donors throughout Japan showed that prevalence of IgG anti-HEV was higher in men (3.9%) than in women (2.9%) [24]. Similar results were also reported in Bangladeshi and Taiwan[25,26]. In this study, jaundice, fatigue and anorexia were most common clinical manifestations. The mortality was 10.0% in our study, higher than the previously reported rate of 1% to 3%. This difference may be mainly due to the sample selection in this study: a considerable proportion of patients whom were hospital referraled from municipal hospitals were critically ill, leading to a high mortality in the overall sample (Tongji hospital is the largest hospital in the middle part of China).

The multivariate analysis showed that TBil, BUN, and INR were major risk factors of mortality for HE, which was useful to assess the prognosis of HE. Infection of HEV in patients on the base of chronic liver diseases could make the chronic liver disease more severe, and cause decomposition and death[27]. Patients with cirrhosis were prone to infect HEV, and the mortality of HEV infected cirrhotics at 4 weeks and 12 month was increased compared with that of non-infected cirrhotics[8]. Our study also showed that the mortality of HEV infected patients with cirrhosis was higher. And the incidence of hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis were higher than HEV infected patients. It reveals that patients with cirrhosis would have a worse condition as well as a poor prognosis. The hepatic reserve function of cirrhotics deteriorated after HEV infection.

In conclusion, we found that TBil, BUN, and INR were major risk factors of mortality of HE based on 210 patients in central of China. Liver cirrhosis could make the HE more severe, and result in a higher mortality. And HEV infection could cause decompensation in patients with cirrhosis. Although the pathogenesis of HE has not been clarified due to the lack of effective cell or animal models of HEV infection, the results are helpful to provide us some ideas for clinical diagnosis, treatment and basic research of HE.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SJZ conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. JJW participated in collecting samples and following up. QY and SXG carried out the molecular genetic studies, participated in the sequence alignment. JZ performed the statistical analysis. NSX and DYT participated in the design of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Shujun Zhang, Email: zsj800809@163.com.

Jingjing Wang, Email: windflower-jerry@163.com.

Quan Yuan, Email: yuanquan@xmu.edu.cn.

Shengxiang Ge, Email: sxge@xmu.edu.cn.

Jun Zhang, Email: zhangj@xmu.edu.cn.

Ningshao Xia, Email: nsxia@xmu.edu.cn.

Deying Tian, Email: dytian@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to P Yin, professor, Public Health College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, for his help in the statistical analysis of this study.

References

- Emerson SU, Purcell RH. Hepatitis E virus. Rev Med Virol. 2003;13:145–154. doi: 10.1002/rmv.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson SU, Purcell RH. Running like water--the omnipresence of hepatitis E. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2367–2368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moaven L, Van Asten M, Crofts N, Locarnini SA. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis E in selected Australian populations. J Med Virol. 1995;45:326–330. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890450316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawczynski K, Aggarwal R, Kamili S. Hepatitis E. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14:669–687. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco A, Miele L, Gasbarrini G, Grillo R. Sporadic HEV hepatitis in Italy. Gut. 2001;48:580. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.4.580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursaget P, Depril N, Buisson Y, Molinie C, Roue R. Hepatitis type E in a French population: detection of anti-HEV by a synthetic peptide-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Res Virol. 1994;145:51–57. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2516(07)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik SR, Aggarwal R, Salunke PN, Mehrotra NN. A large waterborne viral hepatitis E epidemic in Kanpur, India. Bull World Health Organ. 1992;70:597–604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Acharya S, Kumar Sharma P, Singh R, Kumar Mohanty S, Madan K, Kumar Jha J, Kumar Panda S. Hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection in patients with cirrhosis is associated with rapid decompensation and death. J Hepatol. 2007;46:387–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kc S, Sharma D, Basnet BK, Mishra AK. Effect of acute hepatitis E infection in patients with liver cirrhosis. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2009;48:226–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peron JM, Bureau C, Poirson H, Mansuy JM, Alric L, Selves J, Dupuis E, Izopet J, Vinel JP. Fulminant liver failure from acute autochthonous hepatitis E in France: description of seven patients with acute hepatitis E and encephalopathy. J Viral Hepat. 2007;14:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton HR, Hazeldine S, Banks M, Ijaz S, Bendall R. Locally acquired hepatitis E in chronic liver disease. Lancet. 2007;369:1260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Tian D, Zhang Z, Xiong J, Yuan Q, Ge S, Zhang J, Xia N. Clinical significance of anti-HEV IgA in diagnosis of acute genotype 4 hepatitis E virus infection negative for anti-HEV IgM. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2512–2518. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0657-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Sun J, Liu M, Xia L, Zhao C, Harrison TJ, Wang Y. Seroepidemiology and genetic characterization of hepatitis E virus in the northeast of China. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:554–561. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Chi B, Takahashi K, Mishiro S. A genotype IV hepatitis E virus strain that may be indigenous to Changchun, China. Intervirology. 2003;46:252–256. doi: 10.1159/000072436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li RC, Ge SX, Li YP, Zheng YJ, Nong Y, Guo QS, Zhang J, Ng MH, Xia NS. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus infection, rural southern People's Republic of China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1682–1688. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong C, Dai X, Shao JS, Hu K, Meng JH. Identification of genetic diversity of hepatitis E virus (HEV) and determination of the seroprevalence of HEV in eastern China. Arch Virol. 2007;152:739–746. doi: 10.1007/s00705-006-0882-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain SK, Baral P, Hutin YJ, Rao TV, Murhekar M, Gupte MD. A hepatitis E outbreak caused by a temporary interruption in a municipal water treatment system, Baripada, Orissa, India, 2004. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104:66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinja S, Kumar S, Reddy GM, Ratho RK, Kumar R. Investigation of viral hepatitis E outbreak in a town in Haryana. J Commun Dis. 2008;40:249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martolia HC, Hutin Y, Ramachandran V, Manickam P, Murhekar M, Gupte M. An outbreak of hepatitis E tracked to a spring in the foothills of the Himalayas, India, 2005. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28:99–101. doi: 10.1007/s12664-009-0036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamada Y, Yano K, Yatsuhashi H, Inoue O, Mawatari F, Ishibashi H. Consumption of wild boar linked to cases of hepatitis E. J Hepatol. 2004;40:869–870. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda H, Okada K, Takahashi K, Mishiro S. Severe hepatitis E virus infection after ingestion of uncooked liver from a wild boar. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:944. doi: 10.1086/378074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rab MA, Bile MK, Mubarik MM, Asghar H, Sami Z, Siddiqi S, Dil AS, Barzgar MA, Chaudhry MA, Burney MI. Water-borne hepatitis E virus epidemic in Islamabad, Pakistan: a common source outbreak traced to the malfunction of a modern water treatment plant. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:151–157. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koff RS. Hepatitis A. Lancet. 1998;351:1643–1649. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)01304-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda H, Matsubayashi K, Sakata H, Sato S, Kato T, Hino S, Tadokoro K, Ikeda H. A nationwide survey for prevalence of hepatitis E virus antibody in qualified blood donors in Japan. Vox Sang. 2010;99:307–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2010.01362.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrique AB, Zaman K, Hossain Z, Saha P, Yunus M, Hossain A, Ticehurst J, Nelson KE. Population seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus antibodies in rural Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:875–881. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng PN, Wang RH, Wu IC, Wu JC, Tseng KC, Young KC, Chang TT. Seroprevalence of hepatitis E virus infection among institutionalized psychiatric patients in Taiwan. J Clin Virol. 2007;38:44–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Aggarwal R, Naik SR, Saraswat V, Ghoshal UC, Naik S. Hepatitis E virus is responsible for decompensation of chronic liver disease in an endemic region. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23:59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]