Abstract

Background

Auxin signaling is vital for plant growth and development, and plays important role in apical dominance, tropic response, lateral root formation, vascular differentiation, embryo patterning and shoot elongation. Auxin Response Factors (ARFs) are the transcription factors that regulate the expression of auxin responsive genes. The ARF genes are represented by a large multigene family in plants. The first draft of full maize genome assembly has recently been released, however, to our knowledge, the ARF gene family from maize (ZmARF genes) has not been characterized in detail.

Results

In this study, 31 maize (Zea mays L.) genes that encode ARF proteins were identified in maize genome. It was shown that maize ARF genes fall into related sister pairs and chromosomal mapping revealed that duplication of ZmARFs was associated with the chromosomal block duplications. As expected, duplication of some ZmARFs showed a conserved intron/exon structure, whereas some others were more divergent, suggesting the possibility of functional diversification for these genes. Out of these 31 ZmARF genes, 14 possess auxin-responsive element in their promoter region, among which 7 appear to show small or negligible response to exogenous auxin. The 18 ZmARF genes were predicted to be the potential targets of small RNAs. Transgenic analysis revealed that increased miR167 level could cause degradation of transcripts of six potential targets (ZmARF3, 9, 16, 18, 22 and 30). The expressions of maize ARF genes are responsive to exogenous auxin treatment. Dynamic expression patterns of ZmARF genes were observed in different stages of embryo development.

Conclusions

Maize ARF gene family is expanded (31 genes) as compared to Arabidopsis (23 genes) and rice (25 genes). The expression of these genes in maize is regulated by auxin and small RNAs. Dynamic expression patterns of ZmARF genes in embryo at different stages were detected which suggest that maize ARF genes may be involved in seed development and germination.

Background

Auxin signaling plays a vital role in plant growth and development processes like, in apical dominance, tropic responses, lateral root formation, vascular differentiation, embryo patterning and shoot elongation [1]. At the molecular level, most of these processes are controlled by the auxin-response genes [2,3], and auxin responsiveness is conferred to these genes by conserved promoter elements, including TGA-element (AACGAC), AuxRR-core (core of the auxin response region, GGTCCAT) and AuxRE (auxin response element, TGTCTC). Among these, the AuxRE promoter elements are bound and activated by a plant-specific transcription factors which are called as Auxin Response Factors (ARFs) [4-8]. An ARF protein contains a DNA-binding domain (DBD) in the N-terminal region, a middle region that functions as an activation domain (AD) or repression domain (RD) [9,10], and a carboxyl-terminal dimerization domain (CTD) that are similar to those found in the C terminus of Aux/IAAs, which is a protein-protein interaction domain that mediates the homo- and hetero- dimerization of ARFs and also the hetero-dimerization of ARF and Aux/IAA proteins [9-14].

It has been reported that, the ARF proteins are encoded by a large gene family, with 23 and 25 members in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively [15,16]. Expression analysis suggested that these genes are, in general, transcribed in a wide variety of tissues and organs, with an exception of ARF gene cluster on Arabidopsis chromosome 1, which appears to be restricted to embryo genesis/seed development [15]. Classical genetic approaches have led to the identification of ARF gene functions in plant growth and development. For example, arf mutations caused the change in gynoecium patterning (AtARF3) [17-19], impaired hypocotyls response to blue light, growth and auxin sensitivity (AtARF7) [20-24], formation of vascular strands and embryo axis formation (AtARF5) [25], suppression of hookless phenotype and hypocotyl bending (AtARF2) [26-28], hypocotyl elongation, and auxin homeostasis (AtARF8) [29,30]. Moreover, the mutants of AtARF sister pairs generally exhibit a much stronger phenotype than that of single mutants, suggesting that closely related AtARFs have somewhat redundant roles in Arabidopsis [15]. In rice, antisense phenotype of OsARF1 gene showed stunted growth, low vigor, curled leaves and sterility, suggesting that the gene is essential for vegetative and reproductive development [31].

Genetic divergence between Arabidopsis and rice ARF gene family investigated by genome-wide analysis revealed that most of the rice OsARFs are related to Arabidopsis ARFs and fall into sister pairs as in Arabidopsis [16,32]. The first assembly of maize genome sequence has recently been published [33], however, to the best of our knowledge, the maize ARF gene family (ZmARF genes) has not been characterized in detail. In this article, we provide detailed information on the genomic structures, chromosomal locations, sequence homology and expression patterns of 31 maize ARF genes. In addition, the phylogenetic relationship between ARF genes in Arabidopsis, rice and maize were also compared, which will help future studies for elucidating the precise roles of ZmARFs in maize growth and development.

Results

Identification and chromosomal localization of maize ARF genes

Extensive searches of public and proprietary transcript and genomic databases, by using all previously reported ARF proteins from other species as BLAST queries, identified a total of 31 maize ARF genes that have complete sequences in respective bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones. Among these full-length coding sequences of 13 ZmARF genes (ZmARF1, 3, 9, 10, 12, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 25, 27 and 30) were further confirmed by RT-PCR amplification, cloning and sequencing (Additional file 1). The full length coding sequences of the ZmARF genes ranged from 1389 bp (ZmARF31) to 3450 bp (ZmARF20) with the deduced proteins of 462 to 1149 amino acids (Table 1).

Table 1.

ARF gene family in Maize

| Gene Namea |

ORF length (bp)b |

Deduced polypeptidec | Chr. Locusd | Genomic Locuse | ESTg | Physical Blockh |

Block Pairsi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length (aa) | MW (kDa) | PI | BAC |

GenBank Accessions, DNA |

Nearest Markerf |

||||||

| ZmARF1 | 3261 | 1086 | 120.15 | 6.25 | 1.06 | AC208531 | HM004516 | bnlg1057 | CO533792 | ||

| ZmARF2 | 2046 | 681 | 74.53 | 7.93 | 1.08 | AC194848 | HM004517 | umc1096 | BT060467 | 45-49 | 10La |

| ZmARF3 | 2451 | 816 | 90.85 | 6.38 | 2.01 | AC191413 | HM004518 | umc2046 | AY110452 | 68-82 | 4L |

| ZmARF4 | 2808 | 935 | 102.78 | 6.12 | 2.01 | AC204518 | HM004519 | umc1622 | EE039613 | 68-82 | 4L |

| ZmARF5 | 1542 | 513 | 55.44 | 6.40 | 2.03 | AC200303 | HM004520 | umc1021 | BT066632 | 68-82 | 4L |

| ZmARF6 | 1974 | 657 | 72.94 | 6.14 | 2.04 | AC190503 | HM004521 | umc1089 | BT067327 | ||

| ZmARF7 | 2061 | 686 | 76.70 | 6.29 | 3.00 | AC190684 | HM004522 | bnlg108 | EC885481 | ||

| ZmARF8 | 2124 | 707 | 75.35 | 7.10 | 3.01 | AC184124 | HM004523 | phi049 | EU965402 | ||

| ZmARF9 | 2646 | 881 | 97.03 | 6.01 | 3.04 | AC193407 | HM004524 | AI881370 | EE037883 | ||

| ZmARF10 | 2400 | 799 | 89.22 | 6.25 | 3.06 | AC193433 | HM004525 | bnlg1176 | BT055015 | 125-151 | 1L |

| ZmARF11 | 2067 | 688 | 74.98 | 7.28 | 3.07 | AC210193 | HM004526 | pco114882 | DR820421 | 125-151 | 1L |

| ZmARF12 | 2127 | 708 | 77.95 | 7.11 | 3.08 | AC202124 | HM004527 | umc1690 | EU947189 | ||

| ZmARF13 | 2553 | 850 | 93.13 | 7.01 | 4.03 | AC197426 | HM004528 | umc2199 | BT069005 | ||

| ZmARF14 | 2019 | 672 | 74.84 | 6.25 | 4.05 | AC208514 | HM004529 | umc1103 | EE174911 | ||

| ZmARF15 | 2136 | 711 | 75.93 | 7.23 | 4.06 | AC205511 | HM004530 | bnlg1755 | BT087991 | ||

| ZmARF16 | 2718 | 905 | 100.23 | 6.10 | 4.09 | AC195460 | HM004531 | umc1143 | EU955385 | ||

| ZmARF17 | 1935 | 644 | 70.95 | 6.97 | 5.03 | AC184866 | HM004532 | umc2352 | BT066347 | 212-219 | 10La |

| ZmARF18 | 2742 | 913 | 100.89 | 6.54 | 5.03 | AC196992 | HM004533 | umc1315 | EE176799 | ||

| ZmARF19 | 2151 | 716 | 77.51 | 7.14 | 5.03 | AC207656 | HM004534 | umc1610 | AY105182 | ||

| ZmARF20 | 3450 | 1149 | 127.47 | 6.17 | 5.03 | AC194218 | HM004535 | umc1154 | EE290325 | ||

| ZmARF21 | 2097 | 698 | 74.99 | 8.26 | 6. 02 | AC197562 | HM004536 | umc1656 | BT083638 | ||

| ZmARF22 | 2778 | 925 | 102.23 | 6.44 | 6. 02 | AC195867 | HM004537 | bnlg2151 | CA272068 | ||

| ZmARF23 | 2043 | 680 | 73.94 | 6.86 | 6. 06 | AC187896 | HM004538 | umc1103 | BT067427 | ||

| ZmARF24 | 2211 | 736 | 80.45 | 7.84 | 6. 07 | AC204859 | HM004539 | umc1350 | AY109838 | ||

| ZmARF25 | 2406 | 801 | 89.75 | 6.47 | 8.06 | AC203318 | HM004540 | umc1161 | BT067605 | 324-366 | 1L |

| ZmARF26 | 2061 | 686 | 74.34 | 7.10 | 8.09 | AC208613 | HM004541 | umc1638 | BT087971 | 324-366 | 1L |

| ZmARF27 | 3162 | 1053 | 116.73 | 6.67 | 9.01 | AC211017 | HM004542 | umc2335 | CD439516 | ||

| ZmARF28 | 2442 | 813 | 89.69 | 7.14 | 10.03 | AC190927 | HM004543 | umc1863 | BT066544 | ||

| ZmARF29 | 2838 | 945 | 103.82 | 6.31 | 10.07 | AC201888 | HM004544 | pco137895 | CO441386 | 411-420 | 4L |

| ZmARF30 | 2430 | 809 | 90.30 | 6.24 | 10.07 | AC200880 | HM004545 | pco137999 | EC901065 | 411-420 | 4L |

| ZmARF31 | 1389 | 462 | 50.55 | 5.41 | 10.07 | AC190828 | HM004546 | umc1038 | BT067850 | 411-420 | 4L |

a Systematic designation given to maize ARFs in this work.

b Length of open reading frame in base pairs.

c The number of amino acids, molecular weight (kilodaltons), and isoelectric point (pI) of the deduced polypeptides.

d Location of the ZmARF genes to the Chromosome bins.

e BAC name, DNA accession number where the ZmARF gene is present.

f Nearest marker to the ZmARF gene.

g Representative EST/cDNA in GenBank corresponding to ZmARF gene.

h Location of the ZmARF genes to the physical blocks [32].

I Location of the ZmARF genes to the block pairs [32]. Six ZmARF sister pairs are mapped on the same duplicated chromosomal blocks: ZmARF2 and 17 in 10La, ZmARF3 and 30 in 4L, ZmARF4 and 29 in 4L, ZmARF5 and 31 in 4L, ZmARF10 and 25 in 1L, ZmARF11 and 26 in 1L.

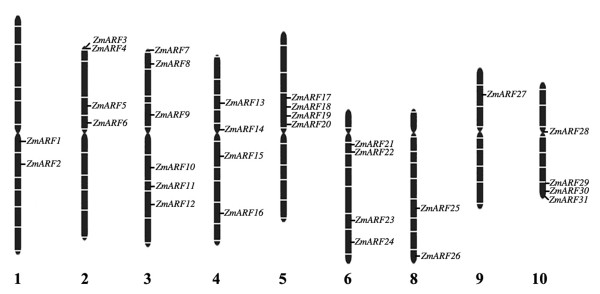

The nearest genetic markers for each ARF gene were determined from maize BAC contigs and positioned on maize genetic map. It was found that these 31 ZmARFs were mapped on 9 out of 10 maize chromosomes, except for chromosome 7. Six ZmARFs were present on chromosome 3; 4 on chromosomes 2, 4, 5, 6 and 10; 2 on chromosomes 1 and 8; only one on chromosome 9 (Table 1, Figure 1). In addition, six ZmARF sister pairs were mapped on the same duplicated chromosomal blocks that has been described previously [34] (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Chromosomal distribution of ARF genes in maize. Constrictions on the chromosomes (vertical bar) indicate the position of centromeres. The chromosome numbers (except for Chromosome 7) are indicated at the bottom of each chromosome image.

The predicted molecular weights of the 31 deduced ZmARF proteins ranged from 50.55 kDa (ZmARF31) to 127.47 kDa (ZmARF20) (Table 1). Pair-wise analysis of ZmARF protein sequences indicated that the overall identity fell in a range within 1.9% (between ZmARF28 and ZmARF31) to 54.3% (between ZmARF11 and ZmARF26) (Additional file 2). Moreover, multiple protein sequence alignments were performed using the CLUSTAL_X program to examine structural features of these 31 maize ARF genes. The results revealed that all the ZmARF proteins contained a highly conserved region of about 320 amino acid residues in their N-terminal portion corresponding to the DNA-binding domain (DBD) of Arabidopsis ARF family. Except ZmARF 5 and 31, the other ZmARF proteins contained a carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD) related to domains III and IV found in Aux/IAA proteins (Additional file 3).

It has been reported that the middle region of ARFs function as activation or repression domains [35]. Transfection assays with plant protoplasts indicated that AtARF1, 2, 3, 4, and 9 are repressors [35,36], among which AtARF1 contain middle region rich in proline (P), serine (S) and threonine (T). AtARF5, 6, 7, 8 and 19, which contain middle region rich in glutamine (Q), are activators [37,38]. The detailed sequence analysis of all 31 deduced ZmARF proteins revealed that PST rich middle regions were found in ZmARF6, 10, 13, 14, 25 and 28, indicating that these genes are more likely to act as repressors. While Q rich regions were found in ZmARF1, 3, 9, 16, 18, 19, 22, 27 and 30, implying that these genes are probable transcriptional activators (Additional file 3).

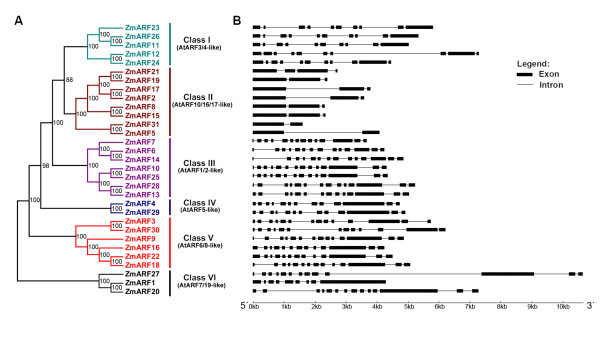

Phylogenetic analysis and genomic structure of ZmARFs

Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was performed and the 31 ZmARF proteins were classified into six classes: Class I (AtARF3/4-like), II (AtARF10/16/17-like), III (AtARF1/2-like), IV(AtARF5-like), V(AtARF6/8-like) and VI(AtARF7/19-like), with each class containing 5, 8, 7, 2, 6 and 3 members, respectively (Figure 2A). It was worthy to note that in the joint phylogenetic tree most of the ZmARF proteins fell as related sister pairs (Figure 2A), viz. ZmARF2 and 17, 3 and 30, 4 and 29, 5 and 31, 6 and 14, 8 and 15, 10 and 25, 12 and 24, 13 and 28, 19 and 21, or triplets (ZmARF11, 23 and 26; 1, 20 and 27) and quadruplets in the case of ZmARF9, 16, 18 and 22.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic relationship among the ZmARF proteins and exon-intron organization of the ZmARF genes. A: Phylogenetic relationship among the maize ARF proteins. The unrooted tree was generated using MRBAYES 3.1.2 program by Bayesian method and the bootstrap test was carried out with 20,000 iterations; Numbers on the nodes indicate clade credibility values; Gene classes were indicated with different colors. B: Exon-intron organization of corresponding ZmARF gene. The exons and introns are represented by boxes and lines, respectively.

The intron/exon structures of ZmARF genes were determined by alignment of cDNA to genomic sequences. This sequence analysis revealed that introns were found in coding sequences of all the ARF genes and the number of exons varied from 2 to 14 (Figure 2B). As expected, most ZmARF genes in the same sister pair or triplets showed similar distribution of intron/exon, whereas the others were more divergent in genomic structure, suggesting that these sister pair genes lies in duplicated genomic regions (Figure 2B).

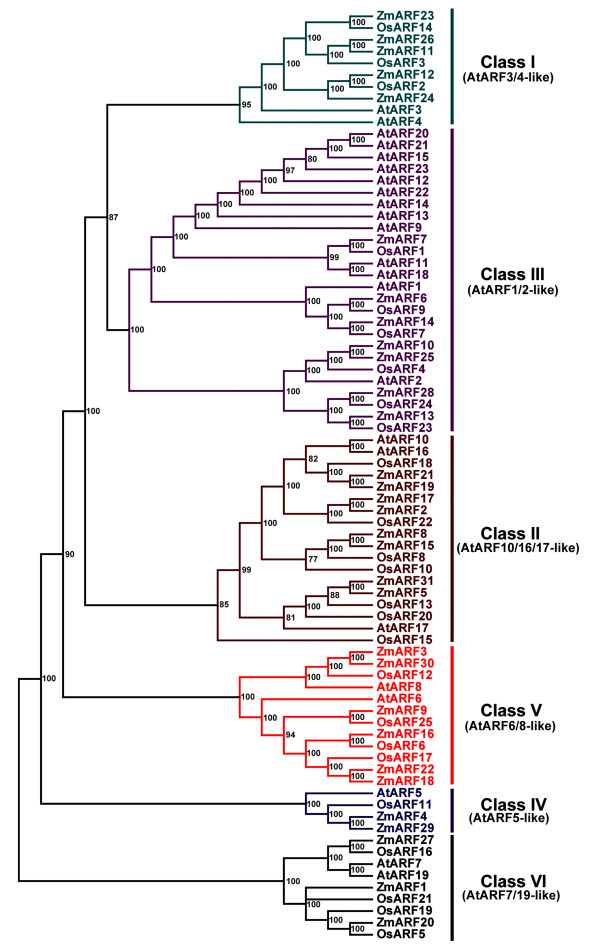

The annotated ARF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice enabled us to determine the phylogenetic relationship between dicot and monocot ARF proteins. A phylogenetic tree constructed using the protein sequences of 31 ZmARFs, 25 OsARFs and 23 AtARFs depicted that all of these 79 ARF proteins were also divided into six classes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of maize, rice and Arabidopsis ARF proteins. The protein sequences of Arabidopsis and rice auxin response factors were obtained from the TIGR database, and phylogenetic analysis was performed with MRBAYES 3.1.2 program by Bayesian method and the bootstrap test was carried out with 1,000,000 iterations; Numbers on the nodes indicate clade credibility values; The gene classes were indicated with the same categories and colors as in Figure 2.

Prediction of potential targets for small RNA

Previous studies have revealed that several ARF genes are targets for small RNAs. For example, AtARF6 and 8 are miR167 targets [39-41] while AtARF10, 16, and 17 are miR160 targets [40,42,43]. AtARF2, 3 and 4 are targets for trans-acting-small interfering RNA 3 (TAS3 ta-siRNA) [40,44]. In this study, putative small RNA target sites were searched by using the miRanda software. 18 out of 31 ZmARF genes were predicted to be the potential targets of small RNA and the number of target genes for miR160, miR167, TAS3 ta-siRNA was 7, 6 and 5, respectively (Additional file 4).

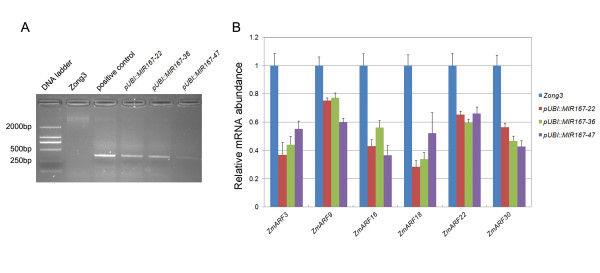

To determine whether the increased miR167 level could cause the degradation of transcripts of the six potential targets (ZmARF3, 9, 16, 18, 22 and 30), we generated miR167 overexpressing Zong3 lines and the presence of transgene was confirmed by PCR amplifications of bar gene (Figure 4A). We then analyzed mRNA levels of these genes in roots of 8-day-old seedling in wild type and miR167 overexpressing Zong3 lines (Figure 4B). The results of real-time RT-PCR exhibited that mRNA abundance of ZmARF3, 9, 16, 18, 22 and 30 in three independent transgenic lines decreased markedly as compared with wild type, indicating that post-transcriptional regulation by small RNAs may play an important role in regulating the expression of ZmARF genes (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Relative mRNA abundances of AtARF6/8-like ZmARFs in wild-type and pre-MIR167b overexpression lines. A. Identification of pre-MIR167b overexpressing transgenic lines by DNA-based bar gene amplification. Amplification products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. B. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed by using cDNAs from roots of 8-day-old seedling of MIR167b transgenic lines (pUBI::MIR167b-22, -36 and -47) and wild type (Zong3).

Auxin inducibility and promoter motif prediction of ZmARF genes

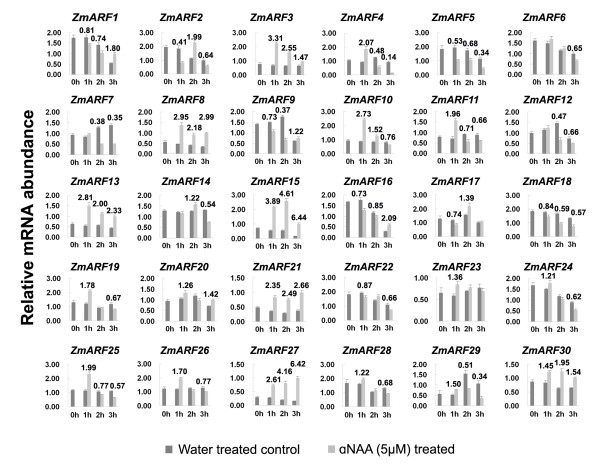

To determine the response of ZmARF genes to exogenous auxin stimuli, their expression patterns in seedling roots at 1, 2 and 3 hours after 5 μM αNAA treatment were investigated using real-time RT-PCR and fold induction relative to water-treated controls for each time point were calculated. This analysis revealed that, with an exception of ZmARF31, all other genes were expressed in seedling roots, among which 7 genes (ZmARF3, 8, 13, 15, 21, 27 and 30) were up-regulated and 2 genes (ZmARF5 and 18) were down-regulated by exogenous auxin treatment across all time points. In addition 7 genes (ZmARF4, 11, 19, 24, 25, 26 and 29) were up-regulated by auxin after 1 h treatment but down-regulated later. In contrast, 3 genes (ZmARF1, 9 and 16) were down-regulated over the first 2 h of treatment but up-regulated after 3 h of auxin treatment. The other 11 ZmARF genes also displayed diverse expression pattern in response to auxin treatment, indicating the complexity of auxin-regulated gene expression of ZmARF genes (Figure 5). Interestingly, the relative mRNA abundance of some ARF genes, for example ZmARF1, 7 and 16, were also altered dramatically in water treatment, indicating that these genes may be responsive to water logging.

Figure 5.

Fold induction of ZmARF genes response to exogenous auxin stimuli. For maize inbred line B73, 8-day-old primary roots were harvested after0, 1, 2 and 3 hours of incubation in 5 μM αNAA and distilled water. Relative mRNA abundance of each gene was normalized with β-Actin gene, with the exception of ZmARF31 (No signal detected in this tissue). Paired t-test was used to determine the significance of differences of relative mRNA abundance between auxin treatment and water control at each time point, and fold induction with significant difference was listed at the top of column.

Putative promoter sequences (1500 bp upstream the 5'UTR region) of ZmARFs were obtained from the draft maize genome sequence. Database search of plant promoters (PlantCARE) [45] detected one or more auxin response elements in some of these putative promoters. Notably, three auxin response elements (2 TGA-elements and 1 AuxRE) were detected in the promoter region of ZmARF15 gene, consistent with its significantly increased mRNA accumulation following auxin treatment. However, out of 31 ZmARFs genes, auxin response elements were detected only in promoter regions of 14 ZmARFs genes (Additional file 5). Thus, the relationship between auxin-response elements and auxin inducibility of ZmARF genes remains unclear and need to be further investigated.

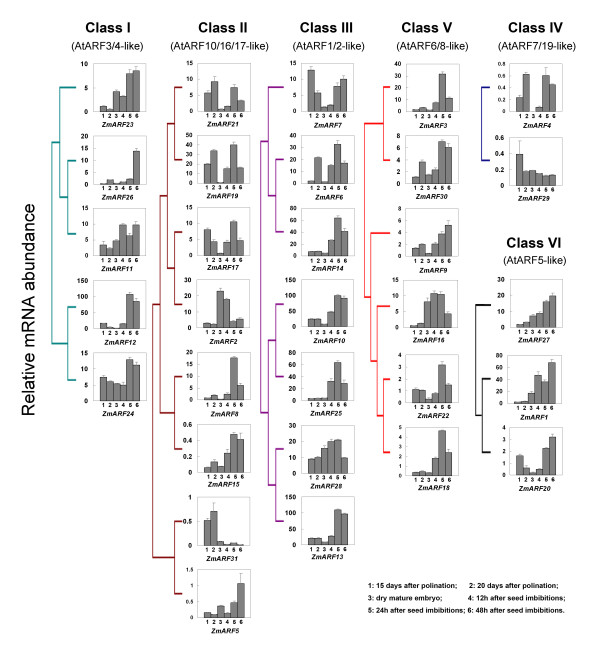

Expression profiling of ZmARF genes in embryos during seed development and germination

Recently, functional analysis has revealed that some ARF genes in Arabidopsis play important role in seed development and germination [28,46]. As a result, we focused on the study of expression patterns of ZmARF genes in embryos during seed development and germination (Figure 6). Expressions of all 31 ZmARF genes were detected but they exhibited dynamic expression patterns, of which 16 genes (51.6%) showed peak expression in embryos at 24 h after imbibition. In addition, the expression patterns of duplicated ZmARF genes also varied considerably. For example, the expression level of ZmARF1 gene was much higher than that of its sister gene ZmARF20 and the time point of peak expression was also different for ZmARF2 and ZmARF17. It is worthy to note that the relative mRNA abundances of 8 ZmARF genes in dry mature embryos were higher than in immature embryos which further increased during seed germination (Figure 6). We observed that the mRNA accumulation of ZmARF2 gene peaked in dry mature embryo but declined after seed imbibition (Figure 6). RT-PCR analysis of embryos (15d after pollination) and two vegetative tissues (8-day-old seedling leaves and roots) detected transcripts of ZmARF genes with an exception of ZmARF31 in 8-day-old seedling leaves and roots (Additional file 6).

Figure 6.

Expression profiling of ZmARF genes in embryos during seed development and germination. For maize inbred line B73, seed embryos of 15 and 20 days after pollination were harvested from greenhouse-grown plants which were planted in a sand/peat under 15 h of light (25°C) and 9 h of dark (20°C) conditions, and embryos were detached from seeds at 0, 12, 24 and 48 h after imbibition in a chamber at 25°C with 12 h light/dark cycle (12 h day/12 h night).

Discussion

Characterization of an expanded ARF gene family in maize

It is believed that the long evolutionary periods experienced by a particular organism is the cause of having multiple members in the specific gene family [16,47]. Several rounds of whole genome duplication have been reported in the maize genome [48]. In this study, we identified and characterized 31 maize ARF genes through genome-wide analysis, suggesting that maize ARF gene family was expanded compared to Arabidopsis (23) and rice (25) [15,16]. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that maize ARF gene family contained ten sister pairs, two triplets and one quadruplet. However, none of these pairs were genetically linked to each other on their corresponding chromosomal locations. On the other hand, all closely linked ZmARF loci such as ZmARF3 and ZmARF4 on chromosome 2; ZmARF17, 18, 19 and 20 on chromosome 5 and ZmARF29, 30 and 31 on chromosome 10 were not paired together into the same sister groups. Moreover, at least six ZmARF sister pairs mapped on the same duplicated chromosomal blocks (Table 1) [34]. Thus, the expansion of maize ARF gene family could be explained by the ancient tetraploid ancestry of maize, in which genome duplication occurred after divergence from the common ancestor of rice and maize, followed by subsequent diploidization en route to modern maize [49-51].

Expression divergence between duplicated ZmARF genes

The presence of duplicated ZmARF genes raises the question about their functional redundancy. According to the evolutionary models, duplicated genes may undergo different selection processes: nonfunctionalization where one copy loses the function, hypofunctionalization where expression/function of one copy decreases, neofunctionalization where one copy gains a novel function, or subfunctionalization where the two copies partition or specialize into distinct functions [52-54]. These evolutionary fates may result in divergence of expression patterns or protein structure. Evidence for divergence between the duplicate genes could be inferred from expression pattern of ZmARF5 and 31 genes. ZmARF5 was highly expressed in seed embryos during germination but the transcript of ZmARF31 was very low. In addition, possible subfunctionalization shifts the expression pattern trends of gene pairs. For example, the mRNA abundance of ZmARF2 peaked in dry mature embryo but ZmARF17 was highly expressed in embryos at 24 h after seed imbibition.

Regulation of ZmARF gene expression

Since ARFs are transcription factors that regulate expression of auxin response genes, it would be interesting to determine the response of ZmARF gene to auxin treatment. It has been reported that Arabidopsis ARF4, 5, 16 and 19 and rice OsARF1 and 23 transcripts increased slightly in response to auxin, while OsARF5, 14 and 21 decreased marginally [15,16,55-57]. In the present study, we found that most of the ZmARF genes were responsive to exogenous auxin treatment but the auxin responsive elements were only detected in promoter region of 14 ZmARF genes. Therefore, the underlying mechanism for auxin inducibility of ZmARF genes needs to be elucidated.

There is a growing body of work showing the posttranscriptional regulation of ARF transcript abundance by micro-RNAs (miRNA or miR) and trans-acting-small interfering RNAs (ta-siRNA) [42]. Regulation of AtARF6 and 8 by miR167 is important for development of anthers and ovules [39-41,58], regulation of AtARF17 by miR160 is important for Arabidopsis growth and development [40] and regulation of AtARF10 and 16 by miR160 plays a role in root cap formation [40,56]. The regulation of AtARF3 and 4 targeted by TAS3 ta-siRNAs is required for proper leaf development [59] and juvenile to adult phase changes [60-62]. The target sites of these three small RNAs were also detected in maize ARF genes, and are widely conserved in dicots and monocots. Furthermore, our transgenic analysis exhibited that increased miR167 level could cause degradation of transcripts for six potential targets (ZmARF3, 9, 16, 18, 22 and 30), indicating that ZmARF genes showed posttranscriptional regulation. However, we found that the expression patterns of ZmARF genes which contained the same target sites varied considerably in embryos during seed development and germination, for example the expression of ZmARF11, 12, 23, 24 and 26 with two potential TAS3 ta-siRNAs recognition sites. Thus, we speculate that some unidentified factors may also play a role in regulating expression of these genes, which could be highly specific to a selected tissue type or developmental program with the possibility that miRNA and tasiRNA may have functions in very discreet regions.

Potential functions of ZmARF genes during seed development

Seed development is considered as a physical link between parents and sporophytic generation in plants [63]. Auxin signaling is thought to play an important role in embryo development. For example, a higher level auxin is detected in root apex and ends of cotyledon primordia from heart to mature embryo in Arabidopsis [64]. Defects in Arabidopsis embryo patterning was observed in arf5 mutants, which enhanced in arf5arf7 double mutants [65]. In this study, seven ZmARF genes, including ZmARF1, 10, 13, 14, 18, 22 and 25, appeared to be constitutively expressed in developing embryos, whereas the transcripts of other ZmARF genes exhibited dynamic expression patterns, suggesting the partitioning of functions between these genes in embryo development.

In most flowering plants, seed germination is the first and may be the foremost growth stage in the plant's life cycle. Genetic evidence supporting a role of ARF genes in germination has been obtained from the analysis of regulation of AtARF10 by miR160 [46]. It has been reported that transgenic seeds of Arabidopsis expressing a miR160-resistant form of AtARF10 (mARF10) are hypersensitive to germination inhibition by exogenous ABA, whereas ectopic expression of miR160 results in a reduced sensitivity to ABA [46]. In the present study, ZmARF2, 5, 8, 15, 17 and 21 are predicted to be the targets for miR160, which falls in the same subfamily with AtARF10, 16 and 17. Expression analysis demonstrated that mRNA accumulation of ZmARF3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 25, 28 and 30 gradually increased during seed germination, reaching its peak in embryos after 24 h of seed imbibition and decreased in later stage, whereas ZmARF2 showed high transcript accumulation in dry seed embryos. In addition, dynamic expression patterns were also observed for other ZmARF genes. Collectively, we speculate that ZmARF genes may be involved in diverse aspects of developmental processes during seed germination.

Conclusions

Maize ARF gene family is expanded as compared to Arabidopsis and rice reflecting a succession of maize genomic rearrangements and expansions due to extensive duplication and diversification that frequently occurred in the course of evolution. The expressions of maize ARF genes are regulated by auxin and small RNAs. Dynamic expression patterns of ZmARF genes in embryo at different stages were observed, which suggest that these genes may be involved in seed development and germination.

Methods

Maize ARF gene identification

A local implementation of NCBI BLASTX was used for sequence searching. All publicly known ARF genes from Arabidopsis (AtARF1-AtARF23) [15] and rice (OsARF1-OsARF25) [16] were used in initial protein queries. Maize (Zea mays) proprietary ESTs and their assemblies, publicly available ESTs, CDS, GSS, BACs, and The Institute for Genomic Research genomic GSS assemblies AZM_4, AZM_5 http://maize.tigr.org/, and MAGI_4 http://magi.plantgenomics.iastate.edu/ were the source for sequences [33]. All potential hits to conserved regions of ARF gene family were assembled and additional rounds of searching were performed to achieve the most possible complete genomic and/or transcript sequences. The Pfam database http://pfam.sanger.ac.uk/search was used to confirm each predicted ZmARF protein sequence as an auxin response factor protein. In addition, full length coding cDNA sequences of 11 ZmARF genes (ZmARF1, 3, 7, 9, 11, 14, 17, 20 22, 24 and 30) were further confirmed by RT-PCR amplification, cloning and sequencing.

Isolation of total RNA and reverse-transcription

Total RNA was isolated using a standard Trizol RNA isolation protocol (Life Technologies, USA) and treated with DNase (Promega Corporation, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The amount and quality of the total RNA was confirmed by electrophoresis in 1% formamide agarose gel. For each plant tissue sample, 2 μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA in 20μl reaction using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega Corporation, USA). Reverse transcription was performed at 37°C for 60 min with a final denaturation step at 95°C for 5 min.

RT-PCR amplification, cloning and sequencing

RT-PCR amplification conditions were optimized from the method described from the previous study [66]. The primer information is given in Additional file 1. For gene cloning, PCR amplified samples were separated in 1.0% agarose gel, purified with Sephaglas BandPrep kit (Amersham Pharmacia, USA), cloned into pGEM-T vector (Promega Corporation, USA) and sequenced by an ABI PRISM 3730 capillary sequencer (PE Applied Biosystem, USA) using an ABI Prism Dye Terminator sequencing kit (PE Applied Biosystem, USA) and either vector or sequence specific primers.

Mapping ZmARF genes on maize chromosomes

All the sequenced contigs of B73, representing the 10 maize chromosomes, have been physically constructed and are publically available. The BAC based physical map generated by fingerprinted contigs http://www.genome.arizona.edu/fpc/maize/WebAGCoL/WebFPC/ was used to find the nearest available markers to position ARF genes on the genetic IBM2 map http://www.maizegdb.org. The distinctive name for each of the ZmARFs identified in this study was given according to its position from the top to the bottom on the maize chromosomes 1 to 10.

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of ZmARFs

The exon/intron structures of the ZmARF genes were determined from alignments of cDNA and genomic sequences using gene structure displayer http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/. The identification of small RNA target sites in ZmARF genes was performed by using miRanda software http://www.miranda-im.org/. Multiple-sequence alignments of ZmARF proteins were carried out using the Clustal_X (version 1.83) program [67]. The protein sequences of Arabidopsis and rice auxin response factors were obtained from the TIGR database and phylogenetic analysis was performed with MRBAYES 3.1.2 program [68] by Bayesian method [69] and the bootstrap test was carried out with 1,000,000 iterations.

Generation of Ubi::MIR167b maize transgenic plants and expression analysis of ZmARFs

A 426 bp fragment for the pre-MIR167b precursor was amplified from maize inbred line Zong3 with the gene-specific primers (5'-GAGGATTGTTTACGCCACCTT-3' and 5'-GGAGAGAATTGAAAGAGAGAGAGGAG-3'). This DNA fragment was verified by sequencing, and ligated into the plant transformation vector pCAMBIA3300, downstream to the ubiquitin promoter. This construct was introduced into maize inbred line Zong3 by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation [70] and the transgenic lines were confirmed by PCR primers (5'-GGTGGACGGCGAGGTCGCCG-3' and 5'-TCGGTGACGGGCAGGACCGG-3') specific to bar gene.

For expression analysis, roots of Zong3 (wild type) line and three homologous pre-MIR167b overexpressing lines (pUBI::MIR167b-22, -36 and -47) were harvested from 8-day-old seedlings grown in a container with tap water under 16 h of light (25°C) and 8 h of dark (20°C). Seedlings were grown in a completely randomized design and three batches of seedlings were used as separate biological replicates. Relative mRNA abundances of six AtARF6/8-like ZmARFs (ZmARF3, 9, 16, 18, 22 and 30) were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR.

Auxin treatment

Seeds of maize inbred line B73 were placed embryo side down on two pieces of Whatman No. 1 filter paper placed in a plastic Petri dish. After overnight imbibition, maize seeds were transferred into a container with tap water and grown in a chamber at constant temperature, (25°C) relative humidity (80%), and subjected to 12 h light/dark cycle (12 h day/12 h night) for 8 days, then transferred to a 5 μM αNAA solution. Control plants were grown in distilled water. Primary roots were isolated after 0, 1, 2 and 3 h of αNAA exposure and from control plants at the same time points and three replicates were harvested for RNA extraction.

Tissue preparations

For maize inbred line B73, embryos of 15 and 20 days after pollination were harvested from greenhouse-grown plants in a sand/peat under 16 h of light (25°C) and 8 h of dark (20°C), and seed embryos at 0, 12, 24 and 48 h after imbibition in a chamber at 25°C with 12 h light/dark cycle (12 h day/12 h night) were detached from seeds. Eight-day-old seedling leaves and roots were harvested for expression analysis.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

Five commonly used housekeeping genes of maize (Additional file 7) were evaluated by geNorm algorithm [71]. Initial steep decrease in average M value of each gene is shown in Additional file 8, which firmly demonstrates that β-Actin is the most stable control gene (with the lowest M value). Real-time RT-PCR reactions were performed according to previous study [72], β-Actin was used as an internal control. Details of primers used in this study are given in Additional file 9, and 2μl aliquots of the cDNA were subjected to expression analysis. The reaction conditions were as follows: 94°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 55-65°C for 30 s, 72°C for 30 s, and a final extension of 72°C for 5 min. Quantification of results were obtained by CFX96™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., USA). cDNAs from three biological samples were used for analysis and all the reactions were run in triplicate. The threshold cycles (Ct) of each tested genes were averaged for triplicate reactions and the values were normalized according to the Ct of the control products of β-Actin gene.

Authors' contributions

HX, GG, GX performed the computational analysis of ARF gene family. RNP coordinated and helped to draft the manuscript. ZH and YZ prepared the materials and did PCR analysis. QS and ZN designed the experiment and prepared the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Primer sequences for full-length cDNA cloning of 13 ZmARFs.

Sequence identity matrix of maize ARF proteins. BioEdit program were employed to examine sequence identity of 31 maize ARF proteins.a

Sequence alignment maize ARF proteins. Clustal_X program were employed to examine sequence features of 31 maize ARF domains.

miR160, 167 and TAS3 target site prediction for ZmARF genes.

Promoter analysis of maize ARFs. Auxin response elements are shown in the list.

The relative expression levels of 31 ZmARFs in three tissues of maize inbred line B73. Leaves (8-day-old seedling), roots (8-day-old seedling) and embryos (15d after pollination) of maize inbred line B73 were used for real-time RT-PCR analysis.

Primers used for stability evaluation of housekeeping gene expression.

Stability evaluation of housekeeping gene expression. Auxin treated 8-day-old primary roots (A) and embryos during seed development and germination (B) were used for evaluating the stability of five housekeeping genes.

Primers used for expression study of ZmARF genes.

Contributor Information

Hongyan Xing, Email: hongyan.xing@gmail.com.

Ramesh N Pudake, Email: rameshnp@gmail.com.

Ganggang Guo, Email: cauguo@gmail.com.

Guofang Xing, Email: xingguofang9596@sina.com.

Zhaorong Hu, Email: hzr803@163.com.

Yirong Zhang, Email: yirongzhang@cau.edu.cn.

Qixin Sun, Email: qxsun@cau.edu.cn.

Zhongfu Ni, Email: wheat3392@cau.edu.cn.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by National Basic Research Program of China (2007CB109000), National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (30925023), National Natural Science Foundation of China (30671297 and 30871577) and 863 Project of China.

References

- Davies PJ. In: Plant Hormones: Physiology, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. Davies PJ, editor. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. The plant hormones: their nature, occurrence and functions. [Google Scholar]

- Abel S, Theologis A. Early genes and auxin action. Plant Physiol. 1996;111:9–17. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilfoyle T, Hagen G, Ulmasov T, Murfett J. How does auxin turn on genes? Plant Physiol. 1998;118:341–347. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Liu ZB, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. Composite structure of auxin response elements. The Plant Cell. 1995;7:1611–1623. doi: 10.2307/3870023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai T, Takahashi Y, Nagata T. Analysis of the promoter of the auxin-inducible gene, parC, of Tobacco. Plant Cell Physiol. 1996;37:906–913. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagao RT, Goekjian VH, Hong JC, Key JL. Identification of protein-binding DNA sequences in an auxin-regulated gene of soybean. Plant Mol Biol. 1993;21:1147–1162. doi: 10.1007/BF00023610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastuglia M, Roby D, Dumas C, Cock JM. Rapid induction by wounding and bacterial infection of an S gene family receptor-like kinase gene in Brassica oleracea. The Plant Cell. 1997;9:49–60. doi: 10.2307/3870370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen G, Guilfoyle T. Auxin-responsive gene expression: genes, promoters and regulatory factors. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;49:373–385. doi: 10.1023/A:1015207114117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Murfett J, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. The Plant Cell. 1997;9:1963–1971. doi: 10.2307/3870557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. Dimerization and DNA binding of auxin response factors. The Plant J. 1999;19:309–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. ARF1, a transcription factor that binds to auxin response elements. Science. 1997;276:1865–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Harter K, Theologis A. Protein-protein interactions among the Aux/IAA proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11786–11791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet F, Overvoorde PJ, Theologis A. IAA17/AXR3: biochemical insight into an auxin mutant phenotype. The Plant Cell. 2001;13:829–841. doi: 10.2307/3871343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin R, Burch AY, Huppert KA, Tiwari SB, Murphy AS, Guilfoyle TJ, Schachtman DP. The Arabidopsis transcription factor MYB77 modulates auxin signal transduction. The Plant Cell. 2007;19:2440–2453. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okushima Y, Overvoorde PJ, Arima K, Alonso JM, Chan A, Chang C, Ecker JR, Hughes B, Lui A, Nguyen D, Onodera C, Quach H, Smith A, Yu G, Theologis A. Functional genomic analysis of the AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR gene family members in Arabidopsis thaliana: unique and overlapping functions of ARF7 and ARF19. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:444–463. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.028316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Pei K, Fu Y, Sun Z, Li S, Liu H, Tang K, Han B, Tao Y. Genome-wide analysis of the auxin response factors (ARF) gene family in rice (Oryza sativa) Gene. 2007;394:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions A, Nemhauser JL, McColl A, Roe JL, Feldmann KA, Zambryski PC. ETTIN patterns the Arabidopsis floral meristem and reproductive organs. Development. 1997;124:4481–4491. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemhauser JL, Feldman LJ, Zambryski PC. Auxin and ETTIN in Arabidopsis gynoecium morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:3877–3888. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.18.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T, Wada T, Yamamoto KT, Okada K. The Arabidopsis STV1 protein, responsible for translation reinitiation, is required for auxin-mediated gynoecium patterning. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:2940–2953. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watahiki MK, Yamamoto KT. The massugu1 mutation of Arabidopsis identified with failure of auxin-induced growth curvature of hypocotyls confers auxin insensitivity to hypocotyl and leaf. Plant Physiol. 1997;115:419–426. doi: 10.1104/pp.115.2.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe-Evans EL, Harper RM, Motchoulski AV, Liscum E. NPH4, a conditional modulator of auxin-dependent differential growth responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1265–1275. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.4.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper RM, Stowe-Evans EL, Luesse DR, Muto H, Tatematsu K, Watahiki MK, Yamamoto K, Liscum E. The NPH4 locus encodes the auxin response factor ARF7, a conditional regulator of differential growth in aerial Arabidopsis tissue. The Plant Cell. 2000;12:757–770. doi: 10.2307/3870999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukaki H, Taniguchi N, Tasaka M. PICKLE is required for SOLITARY-ROOT/IAA14-mediated repression of ARF7 and ARF19 activity during Arabidopsis lateral root initiation. The Plant J. 2006;48:380–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorin C, Bussell JD, Camus I, Ljung K, Kowalczyk M, Geiss G, McKhann H, Garcion C, Vaucheret H, Sandberg G, Bellini C. Auxin and light control of adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis require ARGONAUTE1. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:1343–1359. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardtke CS, Berleth T. The Arabidopsis gene MONOPTEROUS encodes a transcription factor mediating embryo axis formation and vascular development. The EMBO J. 1998;17:1405–1411. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis CM, Nagpal P, Young JC, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ, Reed JW. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR1 and AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR2 regulate senescence and floral organ abscission in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development. 2005;132:4563–4574. doi: 10.1242/dev.02012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Johnson P, Stepanova A, Alonso JM, Ecker JR. Convergence of signaling pathways in the control of differential cell growth in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell. 2004;7:193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schruff MC, Spielman M, Tiwari S, Adams S, Fenby N, Scott RJ. The AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 2 gene of Arabidopsis links auxin signalling, cell division, and the size of seeds and other organs. Development. 2006;133:251–261. doi: 10.1242/dev.02194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian CE, Muto H, Higuchi K, Matamura T, Tatematsu K, Koshiba T, Yamamoto KT. Disruption and overexpression of auxin response factor 8 gene of Arabidopsis affect hypocotyl elongation and root growth habit, indicating its possible involvement in auxin homeostasis in light condition. The Plant J. 2004;40:333–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz M, Vivian-Smith A, Johnson SD, Koltunow AM. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 is a negative regulator of fruit initiation in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2006;18:1873–1886. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attia KA, Abdelkhalik AF, Ammar MH, Wei C, Yang J, Lightfoot DA, El-Sayed WM, El-Shemy HA. Antisense phenotypes reveal a functional expression of OsARF1, an auxin response factor, in transgenic rice. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2009;11:i29–i34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilfoyle TJ, Hagen G. Auxin response factors. Curr Opin Plant Boil. 2007;10:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnable PS, Ware D, Fulton RS, Stein JC, Wei F, Pasternak S, Liang C, Zhang J, Fulton L, Graves TA, Minx P, Reily AD, Courtney L, Kruchowski SS, Tomlinson C, Strong C, Delehaunty K, Fronick C, Courtney B, Rock SM, Belter E, Du F, Kim K, Abbott RM, Cotton M, Levy A, Marchetto P, Ochoa K, Jackson SM, Gillam B. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science. 2009;326:1112–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.1178534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei F, Coe E, Nelson W, Bharti AK, Engler F, Butler E, Kim H, Goicoechea JL, Chen M, Lee S, Fuks G, Sanchez-Villeda H, Schroeder S, Fang Z, McMullen M, Davis G, Bowers JE, Paterson AH, Schaeffer M, Gardiner J, Cone K, Messing J, Soderlund C, Wing RA. Physical and genetic structure of the maize genome reflects its complex evolutionary history. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:1254–1263. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. Activation and repression of transcription by auxin-response factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5844–5849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari SB, Hagen G, Guilfoyle T. The roles of auxin response factor domains in auxin-responsive transcription. The Plant Cell. 2003;15:533–543. doi: 10.1105/tpc.008417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari SB, Wang XJ, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. Aux/IAA proteins are active repressors, and their stability and activity are modulated by auxin. The Plant Cell. 2001;13:2809–2822. doi: 10.2307/3871536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Tiwari SB, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR7 restores the expression of auxin-responsive genes in mutant Arabidopsis leaf mesophy11 protoplasts. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:1979–1993. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MF, Tian Q, Reed JW. Arabidopsis microRNA167 controls patterns of ARF6 and ARF8 expression, and regulates both female and male reproduction. Development. 2006;133:4211–4218. doi: 10.1242/dev.02602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades MW, Reinhart BJ, Lim LP, Burge CB, Bartel B, Bartel DP. Prediction of plant microRNA targets. Cell. 2002;110:513–520. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JH, Han SJ, Yoon EK, Lee WS. Evidence of an auxin signal pathway, microRNA167-ARF8-GH3, and its response to exogenous auxin in cultured rice cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1892–1899. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallory AC, Bartel DP, Bartel B. MicroRNA-directed regulation of Arabidopsis AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR17 is essential for proper development and modulates expression of early auxin response genes. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:1360–1375. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axtell MJ, Bartel DP. Antiquity of microRNAs and their targets in land plants. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:1658–1673. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.032185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams L, Carles CC, Osmont KS, Fletcher JC. A database analysis method identifies an endogenous trans-acting short-interfering RNA that targets the Arabidopsis ARF2, ARF3, and ARF4 genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:9703–9708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504029102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, Rouzé P, Rombauts S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu PP, Montgomery TA, Fahlgren N, Kasschau KD, Nonogaki H, Carrington JC. Repression of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR10 by microRNA160 is critical for seed germination and post-germination stages. The Plant J. 2007;52:133–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilevskaya ON, Meng X, Hou ZL, Ananiev EV, Simmons CR. A genomic and expression compendium of the expanded PEBP gene family from maize. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:250–264. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.109538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Peterson DG, Estill JC, Chapman BA. Structure and evolution of cereal genomes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13:644–650. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Chapman BA. Ancient polyploidization predating divergence of the cereals, and its consequences for comparative genomics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9903–9908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307901101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swigonová Z, Lai J, Ma J, Ramakrishna W, Llaca V, Bennetzen JL, Messing J. Close split of sorghum and maize genome progenitors. Genome Res. 2004;14:1916–1923. doi: 10.1101/gr.2332504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggmann R, Bharti AK, Gundlach H, Lai J, Young S, Pontaroli AC, Wei F, Haberer G, Fuks G, Du C, Raymond C, Estep MC, Liu R, Bennetzen JL, Chan AP, Rabinowicz PD, Quackenbush J, Barbazuk WB, Wing RA, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Rounsley S, Mayer KF, Messing J. Uneven chromosome contraction and expansion in the maize genome. Genome Res. 2006;16:1241–1251. doi: 10.1101/gr.5338906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290:1151–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto SP, Yong P. The evolution of gene duplicates. Adv Genet. 2002;46:451–483. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(02)46017-8. full_text. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte JM, Cui L, Wall PK, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Leebens-Mack J, Ma H, Altman N, dePamphilis CW. Expression pattern shifts following duplication indicative of subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization in regulatory genes of Arabidopsis. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:469–478. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmoth JC, Wang S, Tiwari SB, Joshi AD, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Reed JW. NPH4/ARF7 and ARF19 promote leaf expansion and auxin-induced lateral root formation. The Plant J. 2005;43:118–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JW, Wang LJ, Mao YB, Cai WJ, Xue HW, Chen XY. Control of root cap formation by microRNA-targeted Auxin Response Factors in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2005;17:2204–2216. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.033076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller F, Furuya M, Nick P. OsARF1, an auxin response factor from rice, is auxin-regulated and classifies as a primary auxin responsive gene. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;50:415–425. doi: 10.1023/A:1019818110761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal P, Ellis CM, Weber H, Ploense SE, Barkawi LS, Guilfoyle TJ, Hagen G, Alonso JM, Cohen JD, Farmer EE, Ecker JR, Reed JW. Auxin response factors ARF6 and ARF8 promote jasmonic acid production and flower maturation. Development. 2005;132:4107–4118. doi: 10.1242/dev.01955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D, Collier SA, Byrne ME, Martienssen RA. Specification of leaf polarity in Arabidopsis via the trans-acting siRNA pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:933–938. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragine A, Yoshikawa M, Wu G, Albrecht HL, Poethig RS. SGS3 and SGS2/SDE1/RDR6 are required for juvenile development and the production of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2368–2379. doi: 10.1101/gad.1231804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter C, Willmann MR, Wu G, Yoshikawa M, de la Luz Gutiérrez-Nava M, Poethig SR. Trans-acting siRNA-mediated repression of ETTIN and ARF4 regulates heteroblasty in Arabidopsis. Development. 2006;133:2973–2981. doi: 10.1242/dev.02491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahlgren N, Montgomery TA, Howell MD, Allen E, Dvorak SK, Alexander AL, Carrington JC. Regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR3 by TAS3 ta-siRNA affects developmental timing and patterning in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol. 2006;16:939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng F, Ni Z, Wu L, Sun Q. Differential gene expression between cross-fertilized and self-fertilized kernels during the early stages of seed development in maize. Plant Science. 2005;168:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.07.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ni DA, Wang LJ, Ding CH, Xu ZH. Auxin distribution and transport during embryogenesis and seed germination of Arabidopsis. Cell Res. 2001;11:273–278. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardtke CS, Ckurshumova W, Vidaurre DP, Singh SA, Stamatiou G, Tiwari SB, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ, Berleth T. Overlapping and non-redundant functions of the Arabidopsis auxin response factors MONOPTEROS and NONPHOTOTROPIC HYPOCOTYL 4. Development. 2004;131:1089–1100. doi: 10.1242/dev.00925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HL, Ni ZF, Yao YY, Guo GG, Sun QX. Cloning and expression profiles of 15 genes encoding WRKY transcription factor in wheat (Triticum aestivem L.) Progress in Natural Science. 2008;18:697–705. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsc.2007.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F, Nielsen R, Bollback JP. Bayesian inference of phylogeny and its impact on evolutionary biology. Science. 2001;294:2310–2314. doi: 10.1126/science.1065889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Wei A, Song C, Li N, Zhang J. Heterologous expression of the TsVP gene improves the drought resistance of maize. Plant Biotechnol J. 2008;6:146–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2007.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:research0034.1–0034.11. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou XL, Jiang YY, Liu L, Zhang ZX, Zheng YL. Identification of transcriptome induced in roots of maize seedlings at the late stage of waterlogging. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:189. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primer sequences for full-length cDNA cloning of 13 ZmARFs.

Sequence identity matrix of maize ARF proteins. BioEdit program were employed to examine sequence identity of 31 maize ARF proteins.a

Sequence alignment maize ARF proteins. Clustal_X program were employed to examine sequence features of 31 maize ARF domains.

miR160, 167 and TAS3 target site prediction for ZmARF genes.

Promoter analysis of maize ARFs. Auxin response elements are shown in the list.

The relative expression levels of 31 ZmARFs in three tissues of maize inbred line B73. Leaves (8-day-old seedling), roots (8-day-old seedling) and embryos (15d after pollination) of maize inbred line B73 were used for real-time RT-PCR analysis.

Primers used for stability evaluation of housekeeping gene expression.

Stability evaluation of housekeeping gene expression. Auxin treated 8-day-old primary roots (A) and embryos during seed development and germination (B) were used for evaluating the stability of five housekeeping genes.

Primers used for expression study of ZmARF genes.