Abstract

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were compared as screening tests for current mood disorder in pregnant substance-dependent patients (N = 187). Mean ASI psychiatric Interviewer Severity Rating (ISR) and BDI scores for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder-IV diagnosed current mood disorder patients (n = 51) were 4.4 and 17.1, respectively, and for those without current mood disorder (n = 136) were 2.7 and 14.0, respectively. Areas under receiver operating characteristic curves were 0.73 (ASI) and 0.59 (BDI). The ASI psychiatric ISR predicted mood disorder with better sensitivity and specificity versus the BDI (0.82 and 0.49 for scores ≥4 vs. 0.49 and 0.62 for scores ≥17, respectively).

Keywords: pregnancy, addiction, dual diagnosis, Addiction Severity Index, Beck Depression Inventory, substance abuse

Depressive symptoms affect 8% to 20% of women during pregnancy1-5 with 10% of pregnant women meeting criteria for major depressive disorder.6 Depression during pregnancy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as prematurity and neonatal behavioral effects7-11 and an increased risk of postpartum depression.12 Depressive symptoms during pregnancy among substance-dependent women are higher than in the general population, affecting up to 75% of substance-dependent women.13-16 If left untreated, a mood disorder increases the risk of continued substance abuse during pregnancy17 and is associated with increased pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality.18 Recognition and treatment of mood disorders during pregnancy in both general and substance-dependent populations may lead to improved maternal, fetal, and child health.

It is not known how well or how often substance-abuse treatment practitioners correctly screen and identify depression in pregnancy. Determining the most accurate mood disorder screening measures in pregnant substance-dependent women is needed to assist substance treatment practitioners in making decisions about referrals for psychiatric treatment. Brief screening measures are of particular value, given the heavy paperwork demands of many substance-abuse agencies. Both the Addiction Severity Index (ASI)19 and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)20-22 are widely used as screening tests to determine the need for psychiatric assessment in substance-abuse treatment settings.

The ASI is a semistructured clinical-research interview designed to quantify the multiple health and social problems found among those with substance use disorders. These disturbances are organized into 7 functional domains: alcohol use, drug use, medical health, psychiatric health, etc, employment/self support, family relations, and illegal activity. Lifetime and past 30 days information helps evaluate the duration and severity of each problem and for monitoring change.19 The items in each of the 7 areas have been found to be reliable across interviewers and to have predictive and discriminate validity across a wide range of adult populations.19,23-25 Many studies have shown that Interviewer Severity Ratings (ISRs) are reliable and valid under structured research conditions although, when carried out by less intensively trained and monitored interviewers, these ratings have proven to be less reliable.26-28 In general, however, the psychiatric problem section is considered the most reliable and valid of any ASI domain.19,29 Although little research has been reported with the ASI among drug-using pregnant patients, it has been shown that pregnant women treated with either methadone or medication-assisted withdrawal showed lower Family/Social and Psychiatric and higher Drug and Medical composite scores. These scores were predictive of treatment completion.30,31

The BDI, a 21-item self-rated scale designed to evaluate depression severity, is viewed as one of the better self-report measures of general depression and is a widely used measure in clinical research. The BDI has shown high convergent validity with psychiatric ratings of depression severity in general adult populations.32-34 Its sensitivity (ability to detect episodes of depression when present) in these populations is high. For example, using a cutoff score of 9, the BDI failed to detect only 15.4% of depressed cases.35 Numerous factor analyses have also been conducted on both the first and second versions of the BDI.36 The most common factor structure observed is a 3-factor model of negative self attitudes (cognitive), impairment in functioning (affective), and somatic symptoms.20,37,38 Descriptive studies have focused on collecting normative scores for a variety of patient populations to establish cutoff scores for decision making in research and clinical settings.20 Cutoff scores with patients diagnosed as having a mood disorder are as follows: none or minimal depression is 0 to 9; mild-to-moderate depression is 10 to 18; moderate-to-severe depression is 19 to 29; and severe depression is 30 to 63.20 In other words, a score of 10 or above is suggested to indicate at least mild depressive symptoms in the general population. BDI research involving pregnant women has been conducted primarily in nonsubstance-dependent populations2,39-41 with conflicting results as to the validity of the BDI during pregnancy. BDI research in populations of substance-dependent pregnant women have consistently demonstrated very high BDI scores with over 50% scoring as moderately to severely depressed.13,16,42

Reports comparing the ASI and the BDI against standard diagnostic criteria for depression in pregnant substance-dependent women are lacking. There is no evidence that the ASI psychiatric ISRs or BDI total scores recommended as cutoffs for other populations are appropriate for pregnant substance-dependent women, a group with many symptoms that may mimic those of a mood disorder.

To evaluate a test’s ability to screen for a condition, it is necessary to know the prevalence of the condition and then to calculate sensitivities, specificities, and positive and negative predictive values at various cutoff values for that test. Sensitivity measures how well a screening test identifies the presence of a condition in those with the condition (the ratio of true positives to combined true positives and false negatives). Specificity measures how well a screening test predicts the absence of a condition in those without the condition (the ratio of true negatives to combined false positives and true negatives). Positive predictive value measures how useful a positive test result is (the ratio of true positives to combined true and false positives). Negative predictive value measures how useful a negative test result is (the ratio of true negatives to combined true and false negatives). A likelihood ratio (LR) is the ratio of posttest odds to pretest odds (where pretest odds is the prevalence of the condition) and describes the weight of statistical evidence provided by the screening test by expressing predictive values as odds. For example, if the chance of having the condition, based on the screening test, is 50:50, the LR would be 1.00.

The purpose of this study was to determine the relative value of the ASI psychiatric ISR and the BDI to function satisfactorily as screening tests for mood disorders in a population of pregnant women diagnosed with current substance use disorders.

METHODS

Participants

Between June 2000 and September 2002, 222 pregnant substance-dependent women were admitted to the Johns Hopkins Center for Addiction and Pregnancy (CAP) and signed written informed consent to participate in a larger behavioral study approved by the local Institutional Review Board. Included were participants who tested positive for pregnancy, had evidence of illicit substance use at treatment admission, and completed the study’s assessment battery (N = 187). The assessment battery was completed during an initial 7-day residential stay at the program, and included the ASI-5.0,25 the BDI-I,43 and the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV Axis I Disorders.44 Excluded were pilot participants (n = 16), those who did not complete the initial assessment battery (n = 7) and those who had missing ASI or BDI data (n = 12).

Setting

CAP is a comprehensive service program for substance-dependent pregnant women. Women entering the program typically complete an initial 7-day residential stay, then progress to out-patient treatment, comprised of group and individual drug-counseling sessions. Obstetrical, psychiatric, and pediatric services and daily methadone dispensing (if indicated) are all provided on-site. In addition to these treatment services, the program offers childcare and assistance with transportation to the clinic.45

Assessment

Participants were administered the ASI-5.0.25,46 Within each domain, ISRs ranging from 0 to 9 are given based on a combination of objective and subjective criteria. These ISRs indicate the need for new or additional treatment based on the amount, duration, and intensity of symptoms. The ASI has high test-retest reliability and validity.19

ASI interviewer training included a standardized didactic discussion of the instrument and observation of videotapes provided by the test makers. Interviewers then observed actual interviews administered by an expert interviewer, followed by the administration of participant interviews under the observation of the expert interviewer. Ongoing interrater reliability assessments during the study were conducted and all interviewers participated on a monthly basis. Interrater reliability was based on the ISRs of a sample case reviewed as a group. All interviewers maintained severity ratings within a 3-point range of each other. Additionally, a staff member trained in quality assurance reviewed all interviews following administration to address and resolve coding or interview errors with the interviewers.

Participants completed the BDI-I, a 21-item self-report measure to evaluate depression severity, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 63.43 All completed BDI questionnaires were reviewed by staff for completeness and to address endorsement of suicidal ideation (item 9). Any affirmative response to BDI item 9 (a rating of 1, 2, or 3) prompted the interviewer to complete the program’s suicide assessment protocol. If a participant endorsed current suicidal ideation, her identified mental health counselor was immediately contacted to initiate any necessary safety plans. All cases of acute suicidal ideation were either escorted directly to the emergency room by the mental health counselor or by research staff if the mental health provider was not available.

Participants also completed the SCID-I, a semistructured interview administered to assess for current and lifetime axis I diagnoses.44 It is used in a variety of healthcare settings and has excellent test-retest reliability.47

Interviewer training for the SCID included a didactic review of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder-IV criteria for axis I disorders, a standardized review of the SCID-I instrument, observation of videotapes provided by the test makers, and coding and concordance with taped “gold standard” diagnostic interviews until the interviewer was 100% in agreement with the expert interview. In addition, there was observation by an expert interviewer of the trainee conducting assessments for a minimum of 2 sessions or until there was 100% concordance between interviewers. Finally, trainees were required to pass a knowledge assessment pertaining to DSM-IV criteria for substance abuse and/or dependence. Periodic booster training consisted of each interviewer videotaping sessions for ongoing review.

Procedures

For the present study, all participants met diagnostic criteria for substance dependence based on results from the Substance Use Disorders module of the SCID. These substance-dependent patients were then divided into 2 groups based upon the presence versus absence of a current mood disorder as determined by the Mood Disorders Module of the SCID. Participants meeting criteria for any mood disorder, including major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and substance-induced mood disorder, were assigned to the current mood disorder group.

Data Analysis

SAS Pro Logistic software package was used for statistical analyses (Version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed for the ASI psychiatric ISRs and BDI total scores as predictors of current mood disorder. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were computed, using standard formulae, for various ASI psychiatric ISRs and BDI total cutoff values. Positive and negative LRs were also computed for various ASI and BDI cutoff values. The LR given a positive test result (LR+) was computed using the formula: LR+ = sensitivity/(1−specificity). The LR given a negative test result (LR −) was computed using the formula LR − = (1−sensitivity)/specificity. Pearson χ2 and Levene test were used for comparisons. Spearman ρ was used for nonparametric correlations.

RESULTS

Results first describe the demographic characteristics of the total sample. Next, the pretreatment ASI psychiatric ISRs, BDI scores, and diagnosis of current mood disorder results of the selected sample are presented. These are followed by the ROC curves for the ASI psychiatric ISRs and the BDI scores. Then the sensitivities, specificities, predictive values, and LRs are displayed and, finally, results for the true and false positives and negatives are summarized.

One hundred eighty-seven women were included in this study. The mean (SD) maternal age was 30.1 (5.3) years, mean maternal education was 11.2 (1.6) years, and mean gestational age was 15.7 (6.6) weeks. The participants were predominately African American (71%) and white (26%), and most were currently single (80%). There was no significant correlation between any of these demographic variables and a diagnosis of a current mood disorder (Table 1). Seventy-nine percent of the participants were methadone-maintained.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Pregnant Drug-dependent Women With and Without Current Mood Disorder

| No Current Mood Disorder |

Current Mood Disorder |

Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status (%; N = 187) | ||||

| Married/separated | 16.9 | 27.5 | 19.8 | ns |

| Other | 83.1 | 72.5 | 80.2 | ns |

| Race (%; N = 187) | ||||

| African American | 69.9 | 74.5 | 71.1 | ns |

| White | 27.9 | 19.6 | 25.7 | ns |

| Other | 2.2 | 5.9 | 3.2 | ns |

| Age [mean (SD) y; N = 186] | 29.9 (5.3) | 30.6 (9.4) | 30.1 (5.3) | ns |

| Education [mean (SD) y; N = 187] | 11.1 (1.6) | 11.2 (1.6) | 11.2 (1.6) | ns |

| EGA [mean weeks (SD); N = 186] | 15.9 (7.0) | 15.1 (5.4) | 15.7 (6.6) | ns |

| ASI drug use (any in past 30 d; N = 187) | ||||

| Heroin (%) | 84.7 | 96.2 | 87.8 | — |

| Cocaine (%) | 76.6 | 73.1 | 75.7 | — |

| Alcohol (%) | 45.3 | 50 | 46 | — |

ASI indicates Addiction Severity Index; EGA, estimated gestational age.

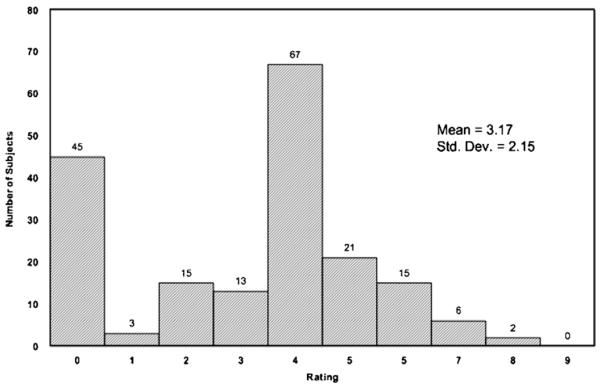

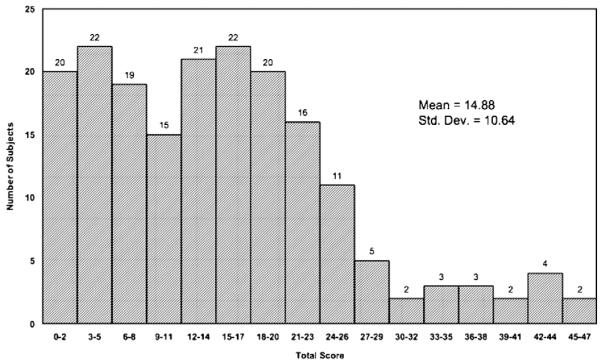

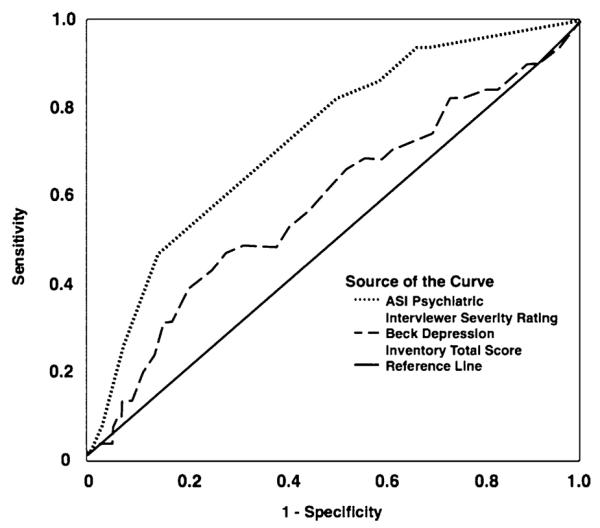

The mean (SD) ASI psychiatric ISR for the 187 women was 3.2 (2.2) and the mean (SD) BDI score was 14.9 (10.6). Fifty-one subjects (27.3%) were diagnosed with current mood disorder by structured interview. The mean (SD) ASI psychiatric ISR for those with current mood disorder was 4.4 (1.7), compared with 2.7 (2.1) for those without current mood disorder. A histogram of all ASI psychiatric ISRs is displayed in Figure 1. The mean (SD) BDI score for those with current mood disorder was 17.1 (11.4), compared with 14.0 (10.3) for those without current mood disorder. A histogram of all BDI scores is displayed in Figure 2. The ROC curves [sensitivity vs. (1−specificity)] are displayed in Figure 3. The area under the curves was 0.73 for the ASI psychiatric ISR and 0.59 for the BDI.

FIGURE 1.

Histogram of Addiction Severity Index Psychiatric Interviewer Severity Ratings* (N = 187). *Maximum possible score = 9.

FIGURE 2.

Histogram of Beck Depression Inventory Scores* (N = 187). *Maximum possible score = 63.

FIGURE 3.

Receiver Operating Characteristic curves for the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) Psychiatric Interviewer Severity Rating, and Beck Depression Inventory score as a Predictor of Current Mood Disorder. The solid diagonal line is the line of no information.

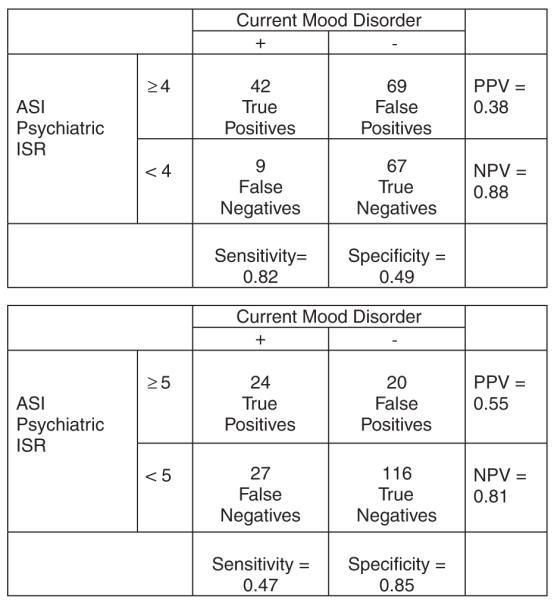

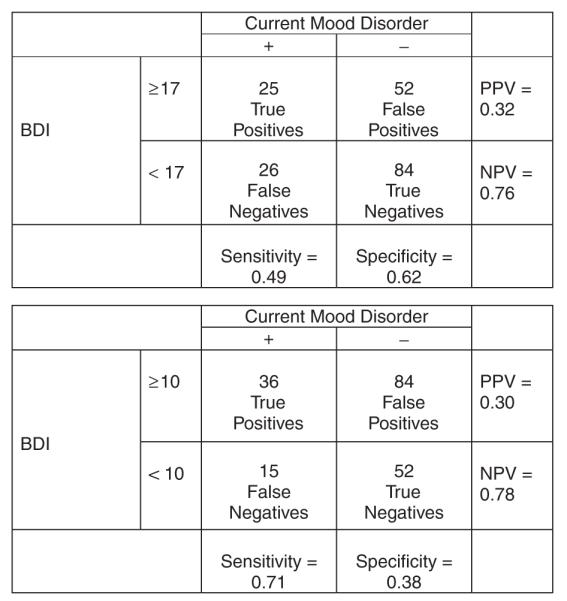

Tables 2 and 3 list the sensitivities, specificities, predictive values, and LRs for various ASI psychiatric ISR and BDI cutoff values. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the relationship of true and false positives and negatives to sensitivity, specificity, gold (reference) standard, positive predictive value, and negative predictive values.

TABLE 2.

Screening Test Characteristics for Various Addiction Severity Index Psychiatric Interviewer Severity Rating Cutoff Values

| Cutoffs | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR − |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥8 | 0.02 | 0.99 | 0.50 | 0.73 | 2.67 | 0.99 |

| ≥7 | 0.08 | 0.97 | 0.50 | 0.74 | 2.67 | 0.95 |

| ≥6 | 0.25 | 0.93 | 0.57 | 0.77 | 3.47 | 0.80 |

| ≥5 | 0.47 | 0.85 | 0.55 | 0.81 | 3.20 | 0.62 |

| ≥4 | 0.82 | 0.49 | 0.38 | 0.88 | 1.62 | 0.36 |

| ≥3 | 0.86 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.89 | 1.47 | 0.33 |

| ≥2 | 0.94 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.94 | 1.41 | 0.18 |

| ≥1 | 0.94 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.93 | 1.36 | 0.19 |

LR+ indicates likelihood ratio with positive result; LR − , likelihood ratio with negative result; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

TABLE 3.

Screening Test Characteristics for Various Beck Depression Inventory Cutoff Values

| Cutoffs | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR − |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥21 | 0.39 | 0.79 | 0.42 | 0.78 | 1.90 | 0.77 |

| ≥20 | 0.43 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 1.73 | 0.76 |

| ≥19 | 0.47 | 0.72 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 1.68 | 0.73 |

| ≥18 | 0.49 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 0.78 | 1.55 | 0.75 |

| ≥17 | 0.49 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 0.76 | 1.28 | 0.83 |

| ≥16 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.33 | 0.77 | 1.31 | 0.79 |

| ≥15 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.32 | 0.77 | 1.27 | 0.78 |

| ≥14 | 0.63 | 0.51 | 0.32 | 0.78 | 1.27 | 0.73 |

| ≥13 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.79 | 1.26 | 0.71 |

| ≥12 | 0.69 | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.79 | 1.23 | 0.71 |

| ≥11 | 0.69 | 0.40 | 0.30 | 0.77 | 1.15 | 0.78 |

| ≥10 | 0.71 | 0.38 | 0.30 | 0.78 | 1.14 | 0.77 |

| ≥9 | 0.73 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.77 | 1.11 | 0.79 |

| ≥8 | 0.75 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.76 | 1.07 | 0.85 |

| ≥7 | 0.82 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 1.12 | 0.67 |

| ≥6 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.79 | 1.09 | 0.73 |

LR+ indicates likelihood ratio with positive result; LR − , likelihood ratio with negative result; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

FIGURE 4.

Addiction Severity Index: test characteristics at 2 sample cutoff values. ISR indicates Interviewer Severity Rating.

FIGURE 5.

Beck Depression Inventory: test characteristics at 2 sample cutoff values.

CONCLUSIONS

This study assessed and compared the psychometric properties of the ASI psychiatric ISR and the BDI as measures of depression in pregnant, substance using women. Participants in the study also were assessed with the SCID, which was used as the gold standard for determining the presence of Major Depression. It was found that 27% of patients in the present study fulfilled a diagnosis of current Major Depression, a prevalence similar to that found in other studies with similar populations.14,15 This consistency in prevalence suggests that the present results may have good generalizability to other pregnant, substance using populations.

The primary finding is that the ASI psychiatric ISR seems to be a better instrument than the BDI for the measurement of depression in this population. This finding is somewhat unexpected, as the BDI was specifically designed to assess depression, whereas the ASI psychiatric ISR was devised for more heterogeneous purposes. One possibility is that the BDI is detecting phenomena other than mood disorder symptoms in pregnant substance-dependent women, such as symptoms related to their pregnancy and/or their substance dependence.39

The BDI is a well-established screening instrument for depression not only in general populations but also in specialized populations like those with substance use disorders and/or pregnancy. It is well accepted that the appropriateness of various cutoff scores for the BDI varies depending on both the nature of the sample and the purposes for which the BDI is being used.20 And several studies have examined the use of the BDI in populations with substance abuse, and in populations of pregnant women. Such studies have shown that there may be a lack of construct stability in patients with severe substance dependence,48 and that higher cut off scores may be more appropriate when the BDI is used in pregnant women.39,49 Although there are markedly fewer studies assessing the use of the BDI in pregnant substance using women, at least 2 studies found this population had mean BDI scores of 9.8 and 10.2,13,16 suggesting high rates of depression for this population.

In the present study, the mean BDI score was 14.8, higher than that reported in these other studies of pregnant substance-dependent women. However, an examination of the BDI’s test characteristics (sensitivities, specificities, predictive values, and LRs) reveals its unsatisfactory performance as a screening test for depression in this population. Although variation is seen among the sensitivities and specificities, the positive and negative predictive values and LRs are relatively similar to one another, making the identification of a clear cutoff value problematic (Table 3). Based upon these results, no BDI score can be designated as superior to another in the detection of depression, and the BDI does not seem to be a useful screening test in this population of pregnant substance-dependent women.

In contrast to the BDI, the ASI was specifically designed for use in substance-using populations. Unlike the BDI, the ASI has not been used or studied in general pregnant populations. Use of the ASI psychiatric ISR as a screening test for depression among nonpregnant substance-dependent populations has been extensively studied and reported,19,23-25,27,29 and psychiatric ISRs of 4 or above have generally been designated as abnormal and worthy of further clinical evaluation.19 Although the ASI is frequently used in programs that treat pregnant substance-dependent women,14,15 the test characteristics of the ASI as a screening test for mood disorder in this population alone or in comparison to the BDI have not been studied. In the present study, 59.4% of the women had an ASI psychiatric ISR of 4 or above, suggesting that a higher value may be needed to screen for depression among pregnant substance-dependent women. Upon examination of the test characteristics (sensitivities, specificities, positive and negative predictive values, and LRs) of the ASI psychiatric ISR in this population, variation in performance was found for various cutoff values (Table 2). In the present study, a cutoff of 4 or above yields a sensitivity of 0.82, a specificity of 0.49, a positive predictive value of 0.38, and a negative predictive value of 0.88.

Clinically, the choice of a cutoff value for a screening test depends not only on disease prevalence but also on the consequences of making, mistaking, or missing a diagnosis. In settings where the treatment of depression is readily accessible, affordable, and effective, a screening test that produces a high rate of false positives has minimal negative consequences (primarily inefficient use of resources due to further evaluation). However, a screening test that produces a high rate of false negatives can have significant adverse consequences, with ramifications for the patient, her pregnancy, and fetal and neonatal outcomes. Thus in such treatment settings, a lower cutoff value is more appropriate. In the present study, however, when a BDI score cutoff value with high specificity was chosen it yielded few missed diagnoses of current mood disorder but resulted in nearly everyone screening positive. Conversely, a cutoff score with high sensitivity yielded an unacceptable number of false-positive results.

Compared with the BDI, in the present study, the ASI psychiatric ISR served as a sensitive screening test for mood disorder during pregnancy for substance-dependent women, with acceptable false-positive results. Therefore, when the prevalence of depression is similar to or exceeds that in our population, an ASI psychiatric ISR can be used to screen women for current mood disorder. Those women who test positive (with an ISR of 4 or above) can then be further assessed to distinguish the occurrence of a current mood disorder from a false-positive test result. These results suggest that the ASI psychiatric ISR performance is superior to the BDI in screening for current mood disorders in a population of pregnant substance-dependent women.

There are several limitations to this study that should be noted. These include the timing of administration of the instruments. BDI scores, for instance, have been shown to be unstable during the first 4 weeks of treatment.50 In addition, giving each woman both the ASI and BDI could have resulted in testing bias whereby one test influenced the other. Other limitations are inclusion of nonmethadone stabilized participants and substance-induced mood disorder participants. To address the former limitation, we performed a secondary data analysis, excluding women who were not methadone-stabilized and found that the ASI psychiatric ISR performed even better (area under the ROC = 0.75) than it had when these participants were included (area = 0.73). In contrast, the BDI performed worse when these nonmethadone-stabilized women were excluded (area under the ROC = 0.55) than when they were included (area = 0.59). The moderate sample size and retrospective secondary data analysis are additional study limitations, and the use of the first version of the BDI. The second, briefer, version of the BDI excludes a number of somatic symptoms36 and might perform better as a depression screening tool than the first version in this population. Although this study demonstrated the ASI’s utility as a screening test for mood disorder, certain issues with the ASI psychiatric ISR must be mentioned. Although ISRs can be reliable and valid, as they were in the present study, training raters can be difficult and the results unreliable in other clinical settings.19 Thus, the use of the ASI suggested by the present study may not be reliably and validly transferred to other pregnant substance-dependent treatment populations with less optimally trained staff administering the ASI. The BDI is self-administered and may be more reliable and valid compared with the ASI in the hands of untrained clinicians. And, regrettably, ISRs will be dropped in the next revision of the ASI19 further limiting the implementation of the present study’s findings.

In conclusion, this study found that the ASI psychiatric ISR can serve as a useful and sensitive screening test for current mood disorder during pregnancy in a population of substance-dependent women, and the ASI psychiatric ISR performed much better than the BDI in these analyses. Pregnant substance-dependent women with an ASI psychiatric ISR score of 4 or above should be referred for psychiatric evaluation as they are at high risk of having a current mood disorder. Future study should focus on identifying which critical objective items within the ASI psychiatric domain and which items, if any, outside the ASI psychiatric domain are most useful in screening for current mood disorder.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Lawrence Mayer for editorial assistance, Linda Felch for statistical analyses, A’Kwaela Morris for data display, and the patients and staff members at CAP.

Supported by NIDA grants DA00332, DA12403 and DA023186.

Footnotes

Portions of these data were presented at the 2007 College on Problems of Drug Dependence scientific meeting.

REFERENCES

- 1.Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, et al. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after child-birth. Br Med J. 2001;323:257–260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gotlib IH, Whiffen VE, Mount JH, et al. Prevalence rates and demographic characteristics associated with depression in pregnancy and the postpartum. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:269–274. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Nelson CB, et al. Sex and depression in the national comorbidity survey. II: Cohort effects. J Affect Disord. 1994;30:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Llewellyn AM, Stowe ZN, Nemeroff CB. Depression during pregnancy and the puerperium. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:26–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FC, et al. Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetrics settings. J Women’s Health. 2003;12:373–380. doi: 10.1089/154099903765448880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, et al. Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:698–709. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000116689.75396.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonari L, Pinto N, Ahn E, et al. Perinatal risks of untreated depression during pregnancy. Canadian J Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne Psychiatrie. 2004;49:726–735. doi: 10.1177/070674370404901103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mian AI. Depression in pregnancy and the postpartum period: balancing adverse effects of untreated illness with treatment risks. J Psychiatr Pract. 2005;11:389–396. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nonacs R, Cohen LS. Depression during pregnancy: diagnosis and treatment options. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orr ST, James SA, Blackmore Prince C. Maternal prenatal depressive symptoms and spontaneous preterm births among African-American women in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:797–802. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wisner KL, Zarin DA, Holmboe ES, et al. Risk-benefit decision making for treatment of depression during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1933–1940. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stowe ZN, Hostetter AL, Newport DJ. The onset of postpartum depression: implications for clinical screening in obstetrical and primary care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:522–526. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burns K, Melamed J, Burns W, et al. Chemical dependence and clinical depression in pregnancy. J Clin Psychol. 1985;41:851–854. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198511)41:6<851::aid-jclp2270410621>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzsimons HE, Tuten M, Vaidya V, et al. Mood disorders affect drug treatment success of drug-dependent pregnant women. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haller DL, Knisely JS, Dawson KS, et al. Perinatal substance abusers. Psychological and social characteristics. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:509–513. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Regan DO, Leifer B, Matteucci T, et al. Depression in pregnant drug-dependent women. NIDA Res Monogr. 1982;41:466–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haller DL, Miles DR, Dawson KS. Psychopathology influences treatment retention among drug-dependent women. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:431–436. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly RH, Russo J, Holt VL, et al. Psychiatric and substance use disorders as risk factors for low birth weight and preterm delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:297–304. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLellan AT, Cacciola J, Alterman AI, et al. The addiction severity index at 25: origins, contributions and transitions. Am J Addict. 2006;15:113–124. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbing MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck depression inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charney DA, Paraherakis AM, Gill KJ. Integrated treatment of comorbid depression and substance use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:672–677. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rounsaville BJ, Weissman MM, Rosenberger PH, et al. Detecting depressive disorders in drug abusers: a comparison of screening instruments. J Affect Disord. 1979;1:255–267. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(79)90012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kosten TR, Rounsaville BJ, Kleber HD. Concurrent validity of the addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;171:606–610. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, et al. New data from the addiction severity index: reliability and validity in three centers. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alterman AI, Brown LS, Zaballero A, et al. Interviewer severity ratings and composite scores of the ASI: a further look. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 1994;34:201–209. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hodgins DC, el-Guebaly N. More data on the addiction severity index. Reliability and validity with the mentally ill substance abuser. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180:197–201. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wertz JS, Cleaveland BL, Stephens RS. Problems in the application of the addiction severity index (ASI) in rural substance abuse services. J Subst Abuse. 1995;7:175–188. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al. Predicting response to alcohol and drug abuse treatments: role of psychiatric severity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:620–625. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.04390010030004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kissin WB, Svikis DS, Moylan P, et al. Identifying pregnant women at risk for early attrition from substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones HE, O’Grady KE, Malfi D, et al. Methadone maintenance versus methadone taper during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Addict. 2008 doi: 10.1080/10550490802266276. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bumberry W, Oliver JM, McClure JN. Validation of the Beck depression inventory in a university population using psychiatric estimate as the criterion. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1978;46:150–155. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Endler NS, Cox BJ, Parker JD, et al. Self-reports of depression and state-trait anxiety: evidence for differential assessment. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1992;63:832–838. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.5.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oliver JM, Simmons ME. Depression as measured by the DSM-III and the Beck depression inventory in an unselected adult population. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52:892–898. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.52.5.892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, Ahnberg JL. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck depression inventory-II. Psychol Assess. 1998;10:83–89. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buckley TC, Parker JD, Heggie J. A psychometric evaluation of the BDI-II in treatment seeking substance abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;20:197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gotlib IH, Cane DB. Construct accessibility and clinical depression: a longitudinal investigation. J Abnormal Psychol. 1987;96:199–204. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holcomb WL, Stone LS, Lustman PJ, et al. Screening for depression in pregnancy: characteristics of the Beck depression inventory. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:1021–1025. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salamero M, Marcos T, Gutierrez F, et al. Factorial study of the BDI in pregnant women. Psychol Med. 1994;24:1031–1035. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700029111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steer RA, Scholl TO, Hediger ML, et al. Self-reported depression and negative pregnancy outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1093–1099. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90149-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reynolds WM, Gould JW. A psychometric investigation of the standard and short form Beck depression inventory. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1981;49:306–307. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 44.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders. State Psychiatric Institute: Biometrics Research; New York, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jansson LM, Svikis D, Lee J, et al. Pregnancy and addiction. A comprehensive care model. J Subs Abuse Treat. 1996;13:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the addiction severity index. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Attainment and maintenance of reliability of axis I and II disorders over the course of a longitudinal study. Compr Psychiatry. 2001;42:369–374. doi: 10.1053/comp.2001.24556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hesse M. The Beck depression inventory in patients undergoing opiate agonist maintenance treatment. Br J Clin Psychol/Br Psychol Society. 2006;45:417–425. doi: 10.1348/014466505x68069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seguin L, Potvin L, St-Denis M, et al. Chronic stressors, social support, and depression during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:583–589. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00449-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strain EC, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. Early treatment time course of depressive symptoms in opiate addicts. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1991;179:215–221. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199104000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]