Abstract

Electrospinning is a process that creates nanofibers through an electrically charged jet of polymer solution or melt. This technique is applicable to virtually every soluble or fusible polymer and is capable of spinning fibers in a variety of shapes and sizes with a wide range of properties to be used in a broad range of biomedical and industrial applications. Electrospinning requires a very simple and economical setup but is an intricate process that depends on several molecular, processing, and technical parameters. This article reviews information on the three stages of the electrospinning process (i.e., jet initiation, elongation, and solidification). Some of the unique properties of the electrospun structures have also been highlighted. This article also illustrates some recent innovations to modify the electrospinning process. The use of electrospun scaffolds in the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine has also been described.

ELECTROSPINNING

A variety of techniques can be used for creating polymeric nanofibers such as drawing, template synthesis, self-assembly, phase separation, and electrospinning.1 Electrospinning is a process of creating solid continuous fibers of material with diameter in the micro- to nanometer range by using electric fields. Compared to mechanical drawing, electrospinning produces fibers of thinner diameters via a contactless procedure.2 It is less complex than self-assembly and can be used for a wide range of materials unlike phase separation. Electrospinning has attracted increased attention in the past few years in a wide range of biomedical and industrial applications due to the ease of forming fibers with a broad range of properties. Electrospinning offers some unique advantages such as high surface to volume ratio, adjustable porosity of electrospun structures, and the flexibility to spin into a variety of shapes and sizes.

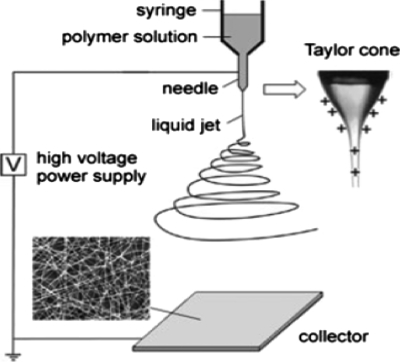

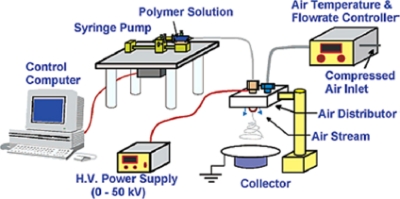

The most basic electrospinning setup consists of three major components: a high voltage power supply, an electrically conducting spinneret, and a collector separated at a defined distance (Fig. 1). In the laboratory, the most common setup is the syringe that holds the polymer solution with a blunt tip needle as the spinneret. With the use of a syringe pump, the solution can be fed at a constant and controllable rate. One electrode from the power supply is connected to the needle holding the spinning solution to charge the polymer solution and the other is attached to an opposite polarity collector (usually a grounded conductor). When the high voltage (typically in the range of 0–30 kV) is applied to the spinneret, the surface of the fluid droplet held by its own surface tension gets electrostatically charged at the spinneret tip. As a result, the drop comes under the action of two types of electrostatic forces: mutual electrostatic repulsion between the surface charges and the Coulombic force applied by the external electric field. Due to these electrostatic interactions, the liquid drop elongates into a conical object known as the Taylor cone. Once the intensity of the electric field attains a certain critical value, the electrostatic forces overcome the surface tension of the polymer solution and force the ejection of the liquid jet from the tip of the Taylor cone. The liquid jet continues to be ejected in a steady manner and the surface tension causes the droplet shape to relax again. Before reaching the collector screen, the liquid jet elongates and the solvent evaporates, leading to the formation of a randomly oriented, nonwoven mat of thin polymeric fibers on the collector.2, 3, 4 Initially, the solution jet follows a linear trajectory, but the jet begins to whip out in chaotic fashion at some critical distance from the spinneret orifice. This is referred to as the bending instability. At the onset of this instability, the jet follows a diverging helical path. As the jet spirals toward the collector, higher order instabilities manifest themselves, resulting in a completely chaotic trajectory.5, 6, 7, 131

Figure 1.

Basic electrospinning setup. Reproduced with permission from D. Li and Y. Xia, Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 16, 1151 (2004). Copyright © 2004 by Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF ELECTROSPINNING

The fundamental idea of electrospinning dates back to 1934. Anton and Formhals8, 9, 10 published a series of patents describing an experimental setup for the production of polymer filaments using an electrostatic force. In 1966, Simons11 patented an apparatus for the production of light weight and ultrathin nonwoven fabrics. He created different patterns using electrical spinning and found that short and fine fibers were formed from low-viscosity solutions, whereas continuous fibers were obtained from more viscous solutions. In 1969, Taylor12 studied the jet produced from the droplet of a polymer solution. He determined that an angle of 49.3° is obtained when the surface tension forces balanced the electric field. The conical shape of the droplet was then referred to as the “Taylor cone” by other researchers.

In 1971, Baumgarten13 made an apparatus to electrospin acrylic fibers with diameters in the range of 500–1100 nm. He demonstrated that the fiber diameter and the concentration of the solution are directly proportional. He showed that the diameter of the jet reached a minimum value after an initial increase in the applied field and then became larger with increasing electric fields. In 1987, Hayati et al.14 studied the factors affecting the jet stability and the electrospinning process. It was found that with increasing applied voltage, highly conducting fluids produced very unstable streams that whipped around in different directions. Semiconducting and insulating liquids, such as paraffin oil, resulted in stable liquid jets.

Research on electrospinning gained momentum in the subsequent years due to increased knowledge on the application potential of nanofibers in various fields such as high efficiency filter media, protective clothing, catalyst substrates, and adsorbent materials. Doshi and Reneker15 studied the characteristics of polyethylene oxide (PEO) nanofibers by varying the solution concentration and the applied electric potential. Jet diameters were measured as a function of the distance from the apex of the cone and it was observed that the jet diameter decreases with the increase in distance. It was found that the PEO solution with viscosity less than 800 cP was too dilute to form a stable jet and solutions with viscosity of more than 4000 cP were too thick to form fibers. Jaeger et al.16 studied the thinning of PEO∕water electrospun fibers and showed that the diameter of the flowing jet decreases as it travels away from the spinneret. Deitzel et al.17 showed that an increase in the applied voltage changes the shape of the surface from which the jet originates and correlated this shape change to the increase in bead defects in fibers. Detailed understanding of the electrospinning process by experimental characterization and evaluation of fluid instabilities was done by Hohman et al.,18, 19 Yarin et al.,7 Warner et al.,20 and Feng.21, 22 Nonlinear rheological constitutive equations applicable for polymer fluids (Ostwald–de Waele power law) were applied to the electrospinning process by Spivak and Dzenis.23 Gibson et al.24 studied the transport properties of the electrospun fiber mats and concluded that nanofibers layers provided less resistance to the moisture vapor diffusion required for evaporative cooling.

In recent years, this simple technique has piqued the interest of many tissue engineers. Various laboratories have effectively electrospun various biodegradable polymers such as poly(glycolic acid) (PGA),25, 26, 27, 28, 29 poly(lactic acid) (PLA),25, 26, 27, 30 copolymers and blends of PGA and PLA,31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 poly(caprolactone) (PCL),37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48 and polydioxanone (PDO),43, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 as well as natural polymers such as collagen (types I–IV),46, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 63, 64, 66, 67, 74, 75 gelatin,35, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92 elastin,50, 57, 83, 93, 94 silk,43, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115 fibrinogen,53, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121 hemoglobin, and myoglobin.122

MODELING OF THE ELECTROSPINNING PROCESS

Electrospinning is a highly coupled process involving high speed nonlinear electrohydrodynamics, complex rheology, and transport of charge, mass, and heat within the jet. The process consists of three stages: jet initiation, jet elongation with or without branching and∕or splitting, followed by solidification of jet into nanofibers. Studies conducted by Rayleigh,123 Zeleny,124 and Taylor12 provided insight into the behavior of the liquid jets.

Jet initiation

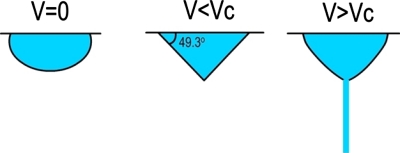

Taylor showed that the a conical surface, referred to as the Taylor cone, is formed with an angle of 49.3° when the droplet is subjected to an external electric field (Fig. 2). Due to the application of the electric field, a charge is induced on the surface of the drop. This charge offsets the forces of surface tension and the droplet changes shape from spherical to conical. When the intensity of the electric field (V) attains a certain critical value (Vc), the electrostatic forces overcome the surface tension of the polymer solution and force the ejection of the liquid jet from the tip of the Taylor cone. The highest charge density is present at the tip of the cone from where the jet is initiated.125 Taylor showed that Vc (in kilovolts) is given by

| (1) |

where H is the air-gap distance, L is the length of the capillary tube, R is the radius of the tube (units: H, L, and R in centimeters), and γ is the surface tension of the fluid (dyn∕cm). The Taylor cone angle has been independently verified by Larrondo and Manley, who experimentally observed that the semivertical cone angle just before jet formation is 50°.126, 127, 128 In another publication, it was reported that the Taylor cone’s angle should be 33.5° instead of 49.3°.129

Figure 2.

Changes in the polymer droplet with applied potential, adapted from Koombhongse et al., Ph.D. Thesis, University of Akron, 2001 (Ref. 130).

Jet thinning

Parameters such as solution concentration, field strength, flow rate, jet velocity and shear rate impact the electrospinning process. In the case of low molecular weight fluids, the rate at which the radius of an electrostatically driven jet decays depends on the flow rate of the polymer solution. If the flow rate is slow, the radius of the jet decays very rapidly. On the other hand, if the flow rate is fast, the radius of the jet decreases slowly. Deitzel et al.131 explained this phenomenon by assuming a simple cylindrical geometry to represent the volume element of the electrospinning jet. From Eq. 2, the ratio of surface area to volume (specific surface area) is inversely proportional to the jet radius. Therefore, an increase in the jet radius results in a corresponding decrease in the specific surface area associated with that specific volume element. If the density of the polymer solution and the surface charge density are assumed to be constant, then it follows that the charge to mass ratio will decrease with increasing jet radius. From Eq. 3, the acceleration is directly proportional to the ratio of charge to mass; hence, an increase in jet radius results in a decrease in the acceleration of the fluid,131

| (2) |

where A is the surface area of the cylindrical volume element, V is the volume, and R is the radius of the jet,

| (3) |

where a is acceleration, E is the electric field strength, q is the available charge for the given volume element, and m is the mass of a given volume element.

It should be noted that this simplified model of a cylinder was only meant to provide a gross illustration of the interaction between the solution feed rate, electrospinning voltage, and the charge to mass ratio. This idea is consistent with the results reported by Baumgarten.13 His experiments illustrated that as the viscosity of the polymer solvent decreased, the spinning drop changed from hemispherical to conical. By using equipotential line approximation calculations, he obtained an expression to calculate the radius r0 of a spherical drop as follows:

| (4) |

where ε is the permittivity of the fluid (C∕V cm), m0 is the mass flow rate (g∕s) at the moment where r0 is to be calculated, k is a dimensionless parameter related to the electric currents, σ is the electric conductivity (A∕V cm), and ρ is the density (g∕cm3). However, for a detailed and accurate description of the fluid flow in the electrospinning jet, various other variables must be taken into consideration, such as viscoelastic response, charge relaxation times, and solvent evaporation rate. All these variables will further complicate the interplay of mechanical and electrostatic forces. The readers are referred to the works of Hohman et al.,18, 19 Yarin et al.,7 Feng21, 22 for a more detailed discussion of these issues.

Jet instabilities

The traveling liquid jet stream is subjected to a variety of forces with opposing effects; as a result, various fluid instabilities also occur in this stage.15 The jet may undergo splitting into multiple subjets in a process known as splaying or branching.132 This happens when changes occur in the shape and charge per unit area of the jet due to its elongation and the evaporation of the solvent. This shifts the balance between the surface tension and the electrical forces, and the jet becomes unstable. In order to reduce its local charge per unit surface area, the unstable jet ejects a smaller jet from the surface of the primary jet.132 An example is shown in Fig. 3. The formation of branches in jets and fibers occurs in more concentrated and viscous solutions and also at unusually high electric fields.6

Figure 3.

SEM of branched fibers from 10% poly(ether imide) in 1,1,1,3,3,3 hexafluoro-2-propanol. Reproduced with permission from S. Koombhongse et al., J. Polym. Sci. 39, 2598 (2001). Copyright © 2001 by John Wiley and Sons.

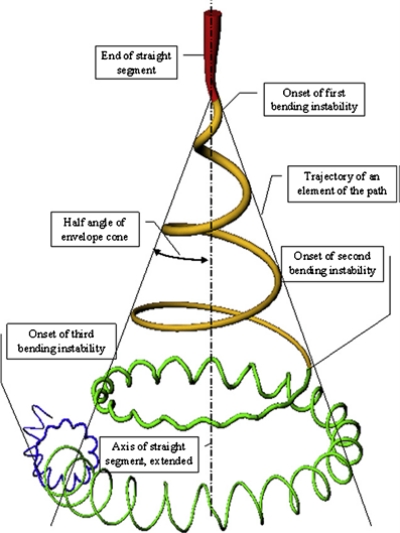

However, the key role in reducing the jet diameter from micrometer to nanometer is played by a nonaxisymmetric or whipping instability, which causes bending or stretching of the jet. When the polymer jet becomes very long and thin, the time required for excess charge to redistribute itself along the full length of the jet becomes longer. The location of the excess charge then tends to change with the elongation. The repulsive Coulomb forces between the charges carried with the jet elongate the jet in the direction of its axis until the jet solidifies. This leads to an incredibly high velocity at the thin leading end of the straight jet. As a result, the jet bends and develops a series of lateral excursions that grow into spiraling loops (Fig. 4). Each of these loops grow larger in diameter as the jet grows longer and thinner.5, 6, 133

Figure 4.

Diagram showing onset and development of bending instabilities. Reprinted with permission from D. H. Reneker and H. Fong, Polymeric Nanofibers, Copyright © 2005 by American Chemical Society.

Hohman et al.18, 19 and Shin et al.134 investigated the stability of electrospinning PEO jet and concluded that the possibility for three types of instabilities exists. The first is the Rayleigh instability, which is axisymmetric with respect to the jet centerline. The second is also an axisymmetric instability and the third is a nonaxisymmetric instability, called “whipping” instability, mainly by the bending force. Rayleigh instability occurs due to opposing forces acting on the surface area of the jet. Electrostatic repulsion of the charges in the jet tends to increase its surface area. On the other hand, the surface tension tends to reduce the total surface area of the jet. Therefore, instability occurs, which causes the jet to break up into droplets, each with a surface area minimizing spherical shape. This effect is known as Rayleigh instability.123 One of these two opposing forces prevails, depending on the nature and mechanical properties of the fluid, especially its viscosity and surface tension. If the viscosity is high and the fluid contains long-chain molecules, the fluid jet stream diameter will continuously decrease until the dried fiber is eventually deposited on the collector. However, if a low-viscosity liquid is used, it cannot pose much resistance against the Rayleigh instability and tends to break up into droplets. If chain molecules are not present or are not long enough to prevent break up, discrete spherical droplets are formed. The electrostatic repulsion between the charged droplets prevents them from coalescing. Due to the increasing charge density on the surface of the shrinking droplets, they explode into even smaller droplets. This process leads to electrospraying.4

Jet solidification

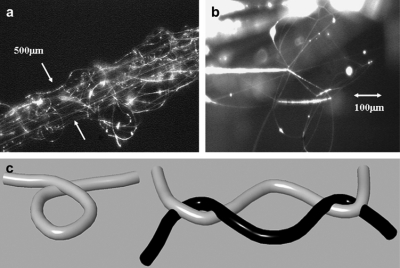

The solidification of the jet results in the deposition of a dry nanofiber on the collector. The solidification rate varies with the polymer concentration, electrostatic field, and gap distance. Yarin et al. used a quasi-one-dimensional equation to describe the mass decrease and volume variation of the fluid jet due to evaporation and solidification, by assuming that there is no branching or splitting from the primary jet. They also reported that the cross-sectional radius of the dry fiber was 1.31×10−3 times that of the initial fluid jet.7 Conglutination is the process by which partially solidified jets can produce fibers that are attached at points of contact. Strong attachments at crossing points stiffen the mat. This is an important factor in determining the mechanical properties of the nonwoven structure. After the onset of bending instability, the jet path may follow a very complicated path and successive loops of coil may touch in flight and form permanent connections. The resulting network formed is called a garland (Fig. 5).37

Figure 5.

(a) A short segment of a garland yarn, (b) details of the conglutinated solid fibers, and (c) a diagram of a loop in a segment of one fiber and another loop. Reprinted with permission from Reneker et al., Polymer 43, 6785 (2002). Copyright © 2002 by Elsevier.

PROPERTIES OF ELECTROSPUN NANOFIBERS

Nanofibers produced by electrospinning exhibit various unique features and properties that are not seen in one-dimensional structures produced by other techniques. Some of the noteworthy properties are described in this section.

Fiber dimension and morphology

The diameter of a fiber produced by electrospinning primarily depends on the spinning parameters, most crucial being the solution concentration. An increase in solution concentration results in fibers with larger diameters. Demir et al.135 reported a power law relationship stating that fiber diameter was proportional to the cube of the polymer concentration. In highly concentrated solutions, a secondary population of smaller fibers may be produced in addition to the primary population once the solution concentration exceeds a certain critical value.17 For example, a bimodal distribution of fiber diameters has been reported to occur in electrospinning of 10 wt % PEO in aqueous solutions. In another example, three different fiber diameters were observed. Electrospinning of polyurethane fibers at 12.8 wt % yielded fibers with primary population of fiber diameter of 1 μm, second approximately 0.4 μm, whereas the tertiary was approximately 1.4 μm.135 The applied electrical voltage is another parameter affecting the fiber diameter. It has been shown that a higher applied voltage results in the ejection of more fluid in a jet, leading to larger fiber diameters. However, when spinning silk-like polymers and bisophenol-A polysulphone, fiber diameter has been shown to decrease with increasing applied voltage.136 Zong et al. studied the impact of solution conductivity on the fiber diameter and found that they are inversely related, i.e., higher solution conductivity results in a smaller fiber diameter. They investigated this phenomenon by adding different salts to polymer spinning solutions. The addition of salts results in higher charge density on the surface of the ejected jet during spinning, thus more electric charges are carried by the electrospinning jet. They also showed that salts with smaller ionic radii produced smaller diameter fibers and vice versa. Overall, they suggested that higher charge density led to higher mobility of ions with smaller radii. Thus, higher mobility resulted in increased elongation forces exerted on the polymer jet creating a smaller fiber.137 Zong et al. also showed that different fiber morphologies can also be obtained by changing the solution feed rate at a given electric field. Low solution feed rates produced fibers with smaller diameters and relatively large fiber diameters were seen in fibers spun from a higher solution feed rate. They reasoned that since the droplet suspended at the end of the spinneret is larger with a higher feed rate, the jet of the solution can carry the fluid away with faster velocity. Therefore, the electrospun fibers may not be completely dry when they reach the target. This can lead to large beads and junctions in the final membrane morphology.

The presence of beads in electrospun fibers is a common problem. The occurrence of beading depends on the various processing variables. With an increase in the applied voltage, jet velocity is increased and the solution is removed from the tip more quickly. When the volume of the droplet on the tip becomes smaller, Taylor cone shape oscillates and becomes asymmetrical. This leads to the formation of beads. The effect of solution concentration on bead formation has also been reported (Fig. 6). Highly concentrated solutions have been shown to produce more uniform fibers with fewer beads. The shape of the beads also changed from spherical to spindlelike when the polymer concentration increased.137 As mentioned above, the addition of salts leads to an increase in the charges carried by the jet and higher elongation forces are imposed to the jet under the electric field. The overall tension in the fibers depends on the self-repulsion of the excess charges on the jet. Therefore, as the charge density increases, the beads become smaller and more spindlelike. Surface tension can also impact the morphology and size of the electrospun fibers. The surface tension of PEO and poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) solutions was lowered by the addition of ethanol.138, 139 In the case of PEO, the solution containing ethanol exhibited less beading. However, when ethanol was added to PVA solutions, beading was increased. The difference observed was attributed to the fact that ethanol is a solvent for PEO but not for PVA.

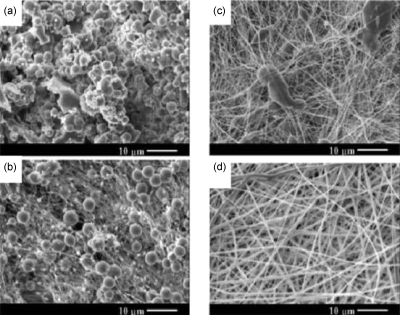

Figure 6.

Concentration effect on microstructures of electrospun poly(D, L-lactic acid) nanofibers at constant processing conditions and variable concentrations of (a) 20 wt % (beads), (b) 25 wt % (beads-on-a-string fibers), (c) 30 wt % (fibers with elongated spindle shaped beads), and (d) 35 wt % (fibers). Reprinted with permission from Zong et al., Polymer 43, 4403 (2002). Copyright © 2002 by Elsevier

Porosity

For a variety of applications, porous fiber surfaces are desired. Electrospun fibers are much thinner in diameter and have high surface to volume ratio as compared to the conventional techniques of fiber fabrication (e.g., extrusion). In electrospun nanofibers, two types of pores can be identified: pores on∕within each fiber and pores between the fibers of a nanofibrous membrane. A high density of pores can be formed due to the entanglement of fibers. When compared to mesoporous materials (e.g., molecular sieves), the specific surface area of the electrospun fibers is lower, but the pores are relatively large and fully interconnected to form a three-dimensional network.2 The knowledge of pore size and porosity is essential in determining the membrane’s performance. Pore size determines the type of substance or species that can permeate through, whereas porosity is a measure of the flow across the membrane. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) can be used to determine the pore size of the electrospun membranes, but not the porosity. Unfortunately with SEM, only the relative pore sizes on the surface can be measured, while pores beneath the surface cannot be analyzed. Nanofiber porosity plays a critical role in various biomedical applications. Sell et al.118 described a method to determine the hydraulic permeability of an electrospun nanofibrous structure to determine its effective pore size and fiber diameter. To enhance porosity of electrospun structures, dual porosity scaffolds can be fabricated by electrospinning a suspension of porogens (i.e., salt and clay particles) in the polymer solution, followed by selective porogen removal. The resulting structures have micron-sized pores formed by the removal of porogens.140 Baker et al. developed an approach to increase the porosity of the electrospun scaffolds by including sacrificial fibers of PEO (a water soluble polymer) in a composite fibrous scaffold. The selective removal of the sacrificial fibers increased the average pore size of the scaffold and enhanced cellular infiltration.141

Surface structure

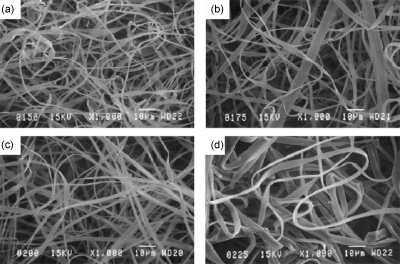

The surface of electrospun fibers is generally smooth; however, it is also dependent on the processing parameters. The use of a low concentration solution or high electrical potential produces beaded electrospun structures that are considerably rougher than completely fibrous structures.142 The cross-sectional shape of electrospun fibers is usually circular. However, in some cases, a skin forms on the polymeric jet and then collapses into a ribbon as the solvent evaporates.132 This results in flattened nanofibers, which are created with high molecular weight polymers and high polymer concentration. The solvent evaporation reduces with higher solution viscosity, resulting in wet fibers that reach the fiber collector and are flattened by the impact. The impact of solution concentration can be seen in Fig. 7. The flat ribbon shape can be attributed to the collapse of an outer skin formed on the surface of the jet. These ribbonlike structures have been observed in the electrospinning of Nylon-6 clay composites, polycarbonates, PVA,4 elastin,57 and hemoglobin.122

Figure 7.

SEM images of electrospun hemoglobin in 2,2,2-Trifluoroethanol at the following concentrations: (a) 150 mg∕mL, (b) 175 mg∕mL, (c) 200 mg∕mL, and (d) 225 mg∕mL (1000× magnification, scale bar is 10 μm). Reproduced courtesy of Barnes et al., Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics (JEFF), 1, 16, 2006.

Chain conformation and crystallinity of nanofibers

Due to the rapid stretching of the electrified jet and the rapid evaporation of the solvent, the polymer chains are expected to experience an extremely strong shear force during the electrospinning process. It has been reported that the magnitude of the strain rate was on the order of around 104∕s in the electrospinning jets.15 This elongational flow tends to force the polymer molecules to orient in the direction of elongation. This rapid stretching and solidification can prevent the polymer chains from relaxing back to their equilibrium conformations. As a result, a higher degree of molecular orientation is found in electrospun nanofibers. As an example, the structures of electrospun PEO were investigated by optical and atomic force microscopy and it was concluded that the fibers possessed a surface layer of highly ordered polymer chains.2

The rapid stretching and solidification of the polymer chains lead to another important effect, the retardation of the crystallization process as the stretched chains do not have enough time for crystal formation. Although the polymer chains are noncrystalline in the nanofibers, they are highly oriented.137 As a result of defects in crystallization, the glass transition temperature and the crystallization peak temperature also decrease.3 Using differential scanning calorimetry and wide angle x-ray diffraction, Deitzel et al. reported poor crystallinity in electrospun PEO fibers.17 Gao et al. also reported weakened crystallinity in electrospun poly (vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) based membranes. However, after thermal treatment, the electrospun membranes exhibited 5%–6% increase in crystallinity, perhaps due to the transformation of some oriented molecular chains in metastable states to crystalline states. They also showed that electrospinning transformed the PVDF materials from the ordered α-type crystal structure to a less-ordered γ-type crystal structure.143 Stephens et al.144 also reported that electrospinning process transformed the Nylon-6 from the α-form to the γ-form.

ELECTROSPINNING INNOVATIONS AND MODIFICATIONS

Several innovative electrospinning processing techniques to enhance the function and properties of electrospun fibers have been described in this section. Desirable physical and biological properties of electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds can be obtained by using these schemes.

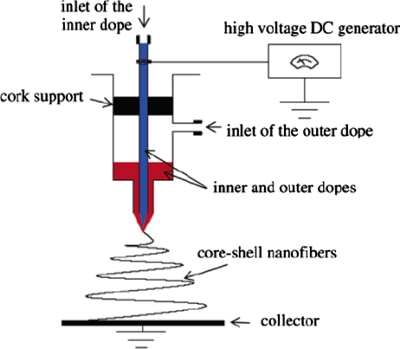

Coaxial electrospinning

In the process of coaxial electrospinning, two polymer solutions can be coelectrospun without direct mixing, using two concentrically aligned nozzles. The same voltage is applied to both nozzles and it deforms the compound droplet. A jet is generated on the tip of the deformed droplet and, in an ideal case, a core-shell nanofiber is formed.145 The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 8. The electrospinning of a concentric jet solution was first reported by Sun et al.146 They successfully created coaxial fibers made of combinations of different materials, PEO-poly(dodecylthiophene), PLA-palladium, and PEO-polysulfone, or of a composition of identical polymers (PEO-PEO) contrasted by dyeing agents such as bromophenole. The fabrication of a core shelled structure with polycaprolactone (PCL) as the shell and gelatin as the core was fabricated by Zhang et al.91 The encapsulation of gelatin within the PCL was confirmed by transmission electron microscopy observation and x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy surface analysis. It was observed that by varying the concentration of the inner dope (gelatin) from 7.5% to 15% (w∕v), both the core and the overall diameters of the resulting nanofibers increased accordingly, while the core volume fraction also followed the same trend. Han et al.147 showed that it is feasible to attach composite nanofibers onto a textile substrate by coaxially spinning PU (shell)∕Nylon-6 (core) nanofibers. In another example, ceramic hollow fibers have been created by coelectrospinning mineral oil as the core with polyvinylpyrrolidone and Ti(OiPr)4 (in ethanol) as the shell. After the removal of the oil and calcinations, hollow titanium fibers were obtained.148, 149 It has been reported that the core-shell nanofibers exhibited properties between those of the individual materials. Overall, this technique can be useful in producing different types of dual composition nanofibers, surface-modified nanofibers, functional graded nanocomposites, and continuous hollow nanofibers. These resulting core-shell structures can also be used for controlled drug release, bioactive tissue scaffolds, and highly sensitive biochemical sensors.145, 146

Figure 8.

Experimental setup for coelectrospinning to produce core-shell nanofibers. Reprinted with permission from Zhang et al., Chem. Mater. 16, 3406 (2004). Copyright © 2004 by American Chemical Society.

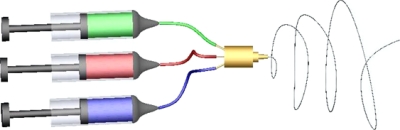

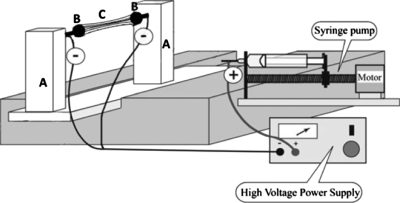

Multilayer and mixed electrospinning

In mixed electrospinning, two or more different polymer solutions can be electrospun from two or more different polymer syringes under different processing conditions (Fig. 9). Multilayer and mixed electrospinning was first demonstrated by Kidoaki et al. to fabricate scaffolds containing three different polymers, segmented PU, styrenated gelatin, and type I collagen for use as an artificial blood vessel.150 The resulting fibrous mesh consisted of layers sequentially collected on the same target collector. Moreover, multilayer electrospinning has been studied using PCL, PLA, PDO, poly(glycolide-co-trimethylene carbonate), gelatin, and elastin. These studies demonstrated different uses of multilayered techniques. Smith et al.54 electrospun PDO-elastin bilayered constructs with a suture wound in the center for reinforcement. Vaz et al.151 electrospun a bilayered tubular structure composed of a stiff and oriented PLA outside fibrous layer and a pliable and randomly oriented PCL fibrous inner layer to be used as vascular graft. These scaffolds were found conducive to fibroblast growth and proliferation. Yang et al.152 created a layered structure of polymers and cells by electrospinning PCL and collagen together, seeding human dermal fibroblasts, and then repeating the polymer and cell layers. These cellularized constructs were done in sheet form and not with tubes. Thomas et al.153 utilized PGA, elastin, and gelatin in a three layered form. However, the use of PGA and gelatin would not be conducive to an arterial graft as gelatin, in vivo, has been shown to display a large cytotoxic response and PGA is a rapidly degrading polymer that would result in arterial graft failure due to loss of mechanical integrity.154 McClure et al. successfully fabricated multilayered electrospun conduit composed of PCL blended with elastin and collagen in the ratio 45:45:10, 55:35:10, and 65:25:10, with distinct material properties for each layer. It was demonstrated that these layers changed the overall graft properties with regard to suture retention and compliance, containing values that were within the range of native artery.39

Figure 9.

Multiple syringe electrospinning setup depicting a three syringe input and a single needle output utilized by McClure et al. (Ref. 39).

Forced air assisted electrospinning

This technique has been used for the electrospinning of aqueous hyaluronic acid (HA) that could not be electrospun using conventional electrospinning due to its very high solution viscosity and high surface tension at fairly low solution concentrations.155 In this process, air flows parallel to the straight portion of the jet concentrically surrounding the polymer jet. The experimental setup is shown in Fig. 10. In this initial study, the air-blowing system was attached to the regular electrospinning apparatus. This resulted in the modified apparatus having two simultaneously applied forces, an electrical force and an air-blowing shear force, to fabricate the nanofibers. The air blow system consisted of two components, a heater and a blower. The air generated by the blower was heated by passing it through the heating elements. It was found by Um et al.155 that the combination of air-blowing force and the applied voltage was capable of overcoming the high viscosity as well as the high surface tension of the HA solution. In addition, the elevated temperature of the blowing air could further reduce the solution viscosity of the HA solution. The air could also aid in faster solvent evaporation. Thus, the fiber diameter could be customized by controlling the flow rate and temperature of the blown air.

Figure 10.

Experimental setup of forced air assisted electrospinning system. Reprinted with permission from Um et al., Biomacromolecules 5, 1428 (2004). Copyright © 2004 by American Chemical Society.

Air-gap electrospinning

Huang et al.3 first developed an approach for fiber alignment by using a rectangular frame structure under the spinning jet. Sell et al.95 described the use of an “air-gap” electrospinner for ligament tissue engineering. This electrospinner (Fig. 11) allowed the creation of three-dimensional constructs composed of highly aligned nanofibers, as opposed to creating compacted aligned constructs through traditional electrospinning techniques. Air-gap electrospinning requires the charged spinneret of the polymer solution to be placed equidistant from a pair of conductive parallel targets. Due to the electric field, the electrospinning jet stretches itself across the air gap and deposits aligned fibers between the charged targets. The charge of the individual fibers creates a mutual repulsion, which enhances their ability to align and be distributed evenly. Using this method, the electrospun scaffold obtained is similar in both overall size and shape as the parallel collecting electrodes. Thus, the shape of the scaffold can be altered by changing the profile of the electrodes. In the air-gap electrospinning system, two stepper motors are mounted on the individual towers to provide rotation of two stainless steel targets (one target per motor). The rotation of the steel targets in the same direction allows for constructs to be created evenly through 360° of rotation or for the stepper motors to be run in opposing directions for a winding action of the constructs to take place during electrospinning. The towers have the ability to translate as well as rotate in order to create structures of different shape and size. Simply by changing the direction and speed of electrode rotation, it is possible to create a number of unique wound and multilayered electrospun constructs with macrostructures significantly different from those created through traditional electrospinning, while maintaining the same microstructure that makes traditional electrospinning so beneficial for tissue engineering. Jha et al.156 fabricated nerve guides of PCL using an air-gap electrospinner. To test the efficacy of the scaffold, they reconstructed 10 mm lesions in the rodent sciatic nerve for placement of the PCL constructs. Microscopic examination of the regenerating tissue revealed dense, parallel arrays of myelinated and nonmyelinated axons, seven weeks postimplantation. Functional blood vessels were also found scattered throughout the implant.

Figure 11.

Air-gap electrospinner setup. Reprinted with permission from Jha et al., Acta Biomaterialia, 7, 203, 2010. Copyright © 2010 by Elsevier.

APPLICATIONS IN TISSUE ENGINEERING AND REGENERATIVE MEDICINE

Electrospun nanofibrous matrices of natural or synthetic origin are widely applicable in the fields of medicine, pharmacy, and biological systems.

Polymeric scaffolds for tissue engineering

One of the most rapidly evolving fields of application for electrospun polymer nanofibers is regenerative medicine. The typical approach in tissue engineering is to use electrospun scaffolds as extracellular matrix (ECM) analogs or support substrates for the cells that have been seeded on them. The electrospun scaffold is then expected to facilitate the anchorage, migration, and proliferation of the cells to reproduce the three-dimensional structure of the tissue to be regenerated. Electrospun scaffolds are attractive to tissue engineering because they have biomimetic properties, characterized by fiber diameters in the submicron range, large surface to volume ratio, high porosity, variable pore size distribution, and the ability to be tailored into a variety of sizes and shapes. In addition, scaffold composition and fabrication can be controlled to match the desired properties and functionality.4, 145, 157 A variety of cell-electrospun matrix interactions have been reported in literature. Typically, the fiber diameters of these matrices conform to the structural properties of the ECM and are on the order of 80–500 nm. It has also been reported that biocompatibility of a material improves with decreasing fiber diameter.158 Another parameter very crucial for cell growth is the degree of porosity and the average pore dimension of the nanofibrous scaffold. Depending upon the cell type, the optimal pore diameters are 20–100 μm.159 It has also been reported that cells are able to easily migrate to a depth of only about 100 μm.92 The role of fiber orientation has also been investigated. It has been observed that growing cells tend to follow the orientation of the fibers. In addition, the production of ECM is greater on oriented rather than nonoriented matrix fibers.160

Several natural and synthetic electrospun polymers have been used to engineer both hard and soft tissues. Natural polymers often lack sufficient strength upon hydration. The mechanical stability of these natural polymers can be improved by either cross-linking or mixing with synthetic polymers.71, 161 One of the most plentiful proteins in the human body is collagen. Collagen fibers display several attractive biological and structural properties. They transmit forces, dissipate energy, prevent premature mechanical failure, and have high water affinity, low antigenicity, and good cell compatibility.162 Various laboratories have worked extensively on the electrospinning of collagen [types I,58 II,68 III,163 and IV163] and blends of collagen with both synthetic and natural polymers to produce scaffolds for vascular,44, 52, 61, 65, 71, 72, 164, 165, 166, 167 skin,46, 62, 69, 168, 169, 170 cartilage,60 bone171, 172 and ligament,173, 174 and nerve70 tissue engineering applications. Elastin is another key protein found in the native ECM of connective tissues where elasticity and recoil are critical parameters. As collagen and elastin are two of the most predominant proteins in the native vessel, they are often used together as tissue engineering scaffolds for vascular scaffolds, with or without synthetic polymers.39, 52, 57, 93, 175, 176 Elastin has also been blended with PLA for urologic tissue engineering.177 Recently, silk fibroin (SF) has gained immense popularity in the field of tissue engineering. SF exhibits good biocompatibility, significant crystallinity, high elasticity, good tensile strength, toughness, and resistance to failure in compression. SF was originally electrospun for ligament95, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182, 183, 184 tissue engineering but has also been used for vascular,43, 114, 185 bone,103, 186 and skin73 tissue engineering. For a detailed review of both synthetic and natural electrospun polymers in tissue engineering, the readers are referred to the works of Sell et al.,71, 161, 187, 188 Ashammakhi et al.,157 and Kumbar et al.189

Nanofiber matrices for release of drugs

Nanofiber systems for the release of drugs are required to fulfill diverse functions. The matrices should be able to protect the compound from decomposition and should allow for controlled release in the targeted tissue, over a desired period of time at a constant release rate.

Kenawy et al. demonstrated the release of tetracycline hydrochloride from electrospun matrices composed of poly[ethylene-co-(vinyl acetate)] (PEVA), PLA, and a 50:50 mixture of the two polymers. The fastest drug release was observed with PEVA, as compared to PLA or the blend. Burst release was observed with PLA, and release properties of the blend were found to be intermediate to those of the pure polymers.190 It was concluded that release kinetics can be altered by changing the polymer used for the fabrication of the nanofibers.

Other parameters that can impact the release kinetics include the morphology of the fibers, their interaction with the drug, and the drug concentration in the fibers. It has been observed that with higher drug concentration, more amount of drug gets enriched on the nanofiber surface, leading to a burst release.191

In another study, water insoluble antitumor drug called paclitaxel and the antituberculosis drug called rifampin were electrospun onto PLA nanofibers. In the presence of proteinase K, it was found that drug release was nearly linear over time. The drug release was attributed to the polymer degradation by the proteinase.192 However, in the case of the hydrophilic drug doxorubicin, burst release was observed. It was reasoned that the hydrophilic nature of the drug caused its accumulation on the surface of the nanofibers, leading to burst release.193 To circumvent this problem, Xu et al.194 electrospun water-oil emulsions, in which the drug was contained in the aqueous phase and a PLA-co-PGA copolymer was contained in the oil phase. This method showed a biomodal release pattern in which burst release was observed initially through diffusion from the fibers, followed by linear drug release through enzymatic degradation of the polymer by proteinase K.

Coaxial electrospinning technique, described previously in Sec. 5A, has also been utilitized for drug delivery. In this system, core immobilizes the drugs and the shell controls their diffusion out of the fibers. Huang et al. used coaxial electrospinning to prepare PCL as the shell and two medically pure drugs, Resveratrol and Gentamycin Sulfate, as the cores. The drugs were released in a controlled way without any initial burst effect.195

Environmentally sensitive polymer drug delivery systems, which can release drugs when triggered by a stimulus (such as pH or temperature), have also been reported. Chunder et al. demonstrated that ultrathin fibers composed of two weak polyelectrolytes poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) and poly(allylamine hydrochloride) could be used for the controlled release of methylene blue through pH changes. They also showed that temperature sensitive drug release can be obtained by depositing temperature sensitive PAA∕poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) multilayers onto the fiber surfaces.196

CONCLUSION

Due to the rising interest in nanoscale materials and properties, research on electrospinning has increased dramatically in the recent years. Using several innovative spinning techniques and modified collectors, structures with different compositions, complex architectures, fiber morphologies, improved properties, varying degradation rates, and functional moieties have been produced. Electrospun nanostructured polymer structures of natural or synthetic origin have a multitude of possible applications in medicine, pharmacy, textiles, optoelectronics, sensor technology, catalysis, and filtration. However, many challenges still exist and a number of fundamental questions still remain open. For instance, it is still difficult to electrospin fibers with diameters below 100 nm. More studies need to be conducted in order to have a better control on the size and morphology of electrospun nanofibers. Due to the molecular weight and solubility limitations of conjugated organic polymers, it has not been possible to electrospin them. Also, a correlation between the processing parameters and the secondary structure of electrospun nanofibers remains to be established. As for tissue engineering applications, all electrospinning techniques described so far lead to the formation of a two-dimensional tissue construct. Improvement in processing technologies to make three-dimensional constructs needs to be done. The production of nanofibers is still primarily in laboratories, and scaled-up commercialization still remains a challenge for many applications. In this paper, a detailed discussion of the intricate electrospinning process and the properties of the nanofibers that make them unique have been discussed. It is hoped that this article will be useful for future research in the field of nanofiber technology.

References

- Ramakrishna S., Fujihara K., Teo W. E., Lim T. C., and Ma Z., An Introduction to Electrospinning and Nanofibers (World Scientific, Singapore, 2005). 10.1142/9789812567611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. and Xia Y., Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 16, 1151 (2004). 10.1002/adma.200400719 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z.-M., Zhang Y.-Z., Kotai M., and Ramakrishna S., Compos. Sci. Technol. 63, 2223 (2003). 10.1016/S0266-3538(03)00178-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burger C., Hsiao B. S., and Chu B., Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 36, 333 (2006). 10.1146/annurev.matsci.36.011205.123537 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reneker D. H., Yarin A. L., Fong H., and Koombhongse S., J. Appl. Phys. 87, 4531 (2000). 10.1063/1.373532 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reneker D. H. and Yarin A. L., Polymer 49, 2387 (2008). 10.1016/j.polymer.2008.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yarin A. L., Koombhongse S., and Reneker D. H., J. Appl. Phys. 89, 3018 (2001). 10.1063/1.1333035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anton F., U.S. Patent No. 2158415 (May 16, 1939).

- Anton F., U.S. Patent No. 2349950 (May 30, 1944).

- Anton F., U.S. Patent No. 1975504 (October 2, 1934).

- Simons H. L., U.S. Patent No. 3,280,229 (October 18, 1966).

- Taylor G., Proc. R. Soc. London, Ser. A 313, 453 (1969). 10.1098/rspa.1969.0205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgarten P. K., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 36, 71 (1971). 10.1016/0021-9797(71)90241-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayati I., Bailey A. I., and Tadros T. F., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 117, 205 (1987). 10.1016/0021-9797(87)90185-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi J. and Reneker D. H., J. Electrost. 35, 151 (1995). 10.1016/0304-3886(95)00041-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger R., Bergshoef M. M., Batlle C. M. I., Schönherr H., and Vancso G. J., Macromol. Symp. 127, 141 (1998). 10.1002/masy.19981270119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deitzel J. M., Kleinmeyer J., Harris D., and Beck Tan N. C., Polymer 42, 261 (2001). 10.1016/S0032-3861(00)00250-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hohman M. M., Shin M., Rutledge G. C., and Brenner M. O., Phys. Fluids 13, 2221 (2001). 10.1063/1.1384013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hohman M. M., Shin M., Rutledge G. C., and Brenner M. O., Phys. Fluids 13, 2201 (2001). 10.1063/1.1383791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warner S. B., Buer A., Grimler M., Ugbolue S. C., Rutledge G. C., and Shin M., National Textile Center Annual Report No. 83, November 1998.

- Feng J. J., Phys. Fluids 14, 3912 (2002). 10.1063/1.1510664 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J. J., J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 116, 55 (2003). 10.1016/S0377-0257(03)00173-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spivak A. F. and Dzenis Y. A., Appl. Phys. Lett. 73, 3067 (1998). 10.1063/1.122674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson P. W., Schreuder-Gibson H. L., and Rivin D., AIChE J. 45, 190 (1999). 10.1002/aic.690450116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- You Y., Min B.-M., Lee S. J., Lee T. S., and Park W. H.., J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 95, 193 (2005). 10.1002/app.21116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong W. H. and Mooney D. J., in Synthetic Biodegradable Polymer Scaffold, edited by Atala A. and Mooney D. J. (Birkhäuser, Boston, 1997), p. 50. [Google Scholar]

- Boland E. D., Pawlowski K. J., Barnes C. P., Simpson D. G., Wnek G. E. and Bowlin G. L., Electrospinning of Bioresorbable Polymers for Tissue Engineering Scaffolds (Oxford University Press, New York, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- Chu C. C. and Browning A., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 22, 699 (1988). 10.1002/jbm.820220804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland E. D., Wnek G. E., Simpson D., Pawlowski K. J., and Bowlin G. L., J. Macromol. Sci., Pure Appl. Chem. 38, 1231 (2001). 10.1081/MA-100108380 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Murugan R., Wang S., and Ramakrishna S., Biomaterials 26, 2603 (2005). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.06.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.-J., Laurencin C. T., Caterson E. J., Tuan R. S., and Ko F. K., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 60, 613 (2002). 10.1002/jbm.10167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong X., Bien H., Chung C.-Y., Yin L., Fang D., Hsiao B. S., Chu B., and Entcheva E., Biomaterials 26, 5330 (2005). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzel J. D., Pawlowski K. J., Wnek G. E., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., J. Biomater. Appl. 16, 22 (2001). 10.1106/U2UU-M9QH-Y0BB-5GYL [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Yu M., Zong X., Chiu J., Fang D., Seo Y.-S., Hsiao B. S., Chu B., and Hadjiargyrou M., Biomaterials 24, 4977 (2003). 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00407-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-W., Yu H.-S., and Lee H.-H., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 87A, 25 (2008). 10.1002/jbm.a.31677 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zong X., Ran S., Kim K.-S., Fang D., Hsiao B. S., and Chu B., Biomacromolecules 4, 416 (2003). 10.1021/bm025717o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reneker D. H., Kataphinan W., Theron A., Zussman E., and Yarin A. L., Polymer 43, 6785 (2002). 10.1016/S0032-3861(02)00595-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto H., Shin Y. M., Terai H., and Vacanti J. P., Biomaterials 24, 2077 (2003). 10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00635-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure M. J., Sell S. A., Simpson D. G., Walpoth B. H., and Bowlin G. L., Acta Biomater. 6, 2422 (2010). 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J., Chen X., Liang Q., Xu X., and Jing X., Macromol. Biosci. 4, 1118 (2004). 10.1002/mabi.200400092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecek C., Yao D., Kaçorri A., Vasquez A., Iqbal S., Sheikh H., Svinarich D. M., Perez-Cruet M., and Rasul Chaudhry G., Tissue Engineering Part A 14, 1403 (2008). 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujihara K., Kotaki M., and Ramakrishna S., Biomaterials 26, 4139 (2005). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure M. J., Sell S., Ayres C. E., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., Biomed. Mater. 4, 055010 (2009). 10.1088/1748-6041/4/5/055010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillman B. W., Yazdani S. K., Lee S. J., Geary R. L., Atala A., and Yoo J. J., Biomaterials 30, 583 (2009). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal J., Zhang Y. Z., and Ramakrishna S., Nanotechnology 16, 2138 (2005). 10.1088/0957-4484/16/10/028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal J. R., Zhang Y. Z., and Ramakrishna S., Artif. Organs 30, 440 (2006). 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2006.00239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson M. R., Black R., and Kielty C., Biomaterials 27, 3608 (2006). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wutticharoenmongkol P., Sanchavanakit N., Pavasant P., and Supaphol O., J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 6, 514 (2006). 10.1166/jnn.2006.090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland E. D., Coleman B. D., Barnes C. P., Simpson D. G., Wnek G. E., and Bowlin G. L., Acta Biomater. 1, 115 (2005). 10.1016/j.actbio.2004.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg K., Sell S. A., Madurantakam P., and Bowlin G. L., Biomed. Mater. 4, 031001 (2009). 10.1088/1748-6041/4/3/031001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure M. J., Sell S. A., Barnes C. P., Bowen W. C., and Bowlin G. L., Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics 3, 1 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- McClure M. J., Sell S. A., Simpson D., and Bowlin G. L., Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics 4, 18 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- McManus M. C., Sell S. A., Bowen W. C., Koo H. P., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics 3, 12 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. J., McClure M. J., Sell S. A., Barnes C. P., Walpoth B. H., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., Acta Biomater. 4, 58 (2008). 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M. J., K. L.White, Jr., Smith D. C., and Bowlin G. L., Biomaterials 30, 149 (2009). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C. P., Pemble C. W., Brand D. D., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., Tissue Eng. 13, 1593 (2007). 10.1089/ten.2006.0292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland E. D., Matthews J. A., Pawlowski K. J., Simpson D. G., Wnek G. E., and Bowlin G. L., Front. Biosci. 9, 1422 (2004). 10.2741/1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews J. A., Wnek G. E., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., Biomacromolecules 3, 232 (2002). 10.1021/bm015533u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields K. J., Beckman M. J., Bowlin G. L., and Wayne J. S., Tissue Eng. 10, 1510 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C. P., Biomedical Engineering (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, 2007), p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C. P., Sell S., Knapp D., Walpoth B. H., Brand D. D., and Bowlin G. L., International Journal of Electrospun Nanofibers 1, 73 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. J., Chang G. Y., and Chen J. K., Colloids Surf., A 313–314, 183 (2008). 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2007.04.129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. S., Lee S. J., Christ G. J., Atala A., and Yoo J. J., Biomaterials 29, 2899 (2008). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong B., Arnoult O., Smith M. E., and Wnek G. E., Macromol. Rapid Commun. 30, 539 (2009). 10.1002/marc.200800634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W., Yong T., Teo W.-E., Ma Z., and Ramakrishna S., Tissue Eng. 11, 1574 (2005). 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Nagapudi K., Apkarian R. P., and Chaikof E. L., J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed. 12, 979 (2001). 10.1163/156856201753252516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon I. K. and Matsuda T., Biomacromolecules 6, 2096 (2005). 10.1021/bm050086u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews J. A., Boland E. D., Wnek G. E., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 18, 125 (2003). 10.1177/0883911503018002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rho K. S., Jeong L., Lee G., Seo B.-M., Park Y. J., Hong S.-D., Roh S., Cho J. J., Park W. H., and Min B.-M., Biomaterials 27, 1452 (2006). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnell E., Klinkhammer K., Balzer S., Brook G., Klee D., Dalton P., and Mey J., Biomaterials 28, 3012 (2007). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S. A., McClure M. J., Garg K., Wolfe P. S., and Bowlin G. L., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 61, 1007 (2009). 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal J., Ma L. L., Yong T., and Ramakrishna S., Cell Biol. Int. 29, 861 (2005). 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo I.-S., Oh J.-E., Jeong L., Lee T. S., Lee S. J., Park W. H., and Min B.-M., Biomacromolecules 9, 1106 (2008). 10.1021/bm700875a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong S., Teo W. E., Zhu X., Beuerman R., Ramakrishna S., and L. Y. L.Yung, Biomacromolecules 6, 2998 (2005). 10.1021/bm050318p [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres C. E., Bowlin G. L., Pizinger R., Taylor L. T., Keen C. A., and Simpson D. G., Acta Biomater. 3, 651 (2007). 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres C. E., Jha B. S., Meredith H., Bowman J. R., Bowlin G. L., Henderson S. C., and Simpson D. G., J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed. 19, 603 (2008). 10.1163/156856208784089643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong E. J., Phan T. T., Lim I. J., Zhang Y. Z., Bay B. H., Ramakrishna S., and Lim C. T., Acta Biomater. 3, 321 (2007). 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L., Prabhakaran M. P., Morshed M., Nasr-Esfahani M.-H., and Ramakrishna S., Biomaterials 29, 4532 (2008). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. W., Song J. H., and Kim H. E., Adv. Funct. Mater. 15, 1988 (2005). 10.1002/adfm.200500116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. E., Heo D. N., Lee J. B., Kim J. R., Park S. H., Jeon S. H., and Kwon I. K., Biomed. Mater. 4, 1 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., He A., Zheng J., and Han C. C., Biomacromolecules 7, 2243 (2006). 10.1021/bm0603342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Guo Y., Wei Y., MacDiarmidc A. G., and Lelkes P. I., Biomaterials 27, 2705 (2006). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Mondrinos M. J., Chen X., Gandhi M. R., Ko F. K., and Lelkes P. I., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 79A, 963 (2006). 10.1002/jbm.a.30833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell H. M. and Boyce S. T., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 84A, 1078 (2008). 10.1002/jbm.a.31498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson K., Zhang C., Farach-Carson M. C., Chase D. B., and Rabolt J. F., Biomacromolecules 10, 1675 (2009). 10.1021/bm900036s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisson K., Zhang C., Farach-Carson M. C., Chase D. B., and Rabolt J. F., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 94A, 1312 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.-H., Kim H.-E., and Kim H.-W., J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Med. 19, 95 (2008). 10.1007/s10856-007-3169-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songchotikunpan P., Tattiyakul J., and Supaphol P., Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 42, 247 (2008). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2007.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan H., Wu J., Lao L., and Gao C., Acta Biomater. 5, 328 (2009). 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S., Huang Y., Yang X., Mei F., Ma Q., Chen G., Ryu S., and Deng X., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 90, 671 (2009). 10.1002/jbm.a.32136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Huang Z.-M., Xu X., Lim C. T., and Ramakrishna S., Chem. Mater. 16, 3406 (2004). 10.1021/cm049580f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ouyang H., Lim C. T., Ramakrishna S., and Huang Z.-M., J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part B: Appl. Biomater. 72B, 156 (2005). 10.1002/jbm.b.30128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttafoco L., Kolkman N. G., Engbers-Buijtenhuijs P., Poot A. A., Dijkstra P. J., Vermes I., and Feijen J., Biomaterials 27, 724 (2006). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S. A., McClure M., Barnes C. P., Knapp D. C., Walpoth B. H., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., Biomed. Mater. 1, 72 (2006). 10.1088/1748-6041/1/2/004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S. A., McClure M. J., Ayres C. E., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., “Preliminary investigation of airgap electrospun silk fibroin-based structures for ligament analogue engineering,” J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed. 22, 1253 (2010). 10.1163/092050610X504251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandrino A., Marelli B., Arosio C., Fare S., Tanzi M. C., and Freddi G., Eng. Life Sci. 8, 219 (2008). 10.1002/elsc.200700067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gui-Bo Y., You-Zhu Z., Shu-Dong W., De-Bing S., Zhi-Hui D., and Wei-Guo F., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 93A, 158 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong L., Lee K. Y., and Park W. H., Key Eng. Mater. 342–343, 813 (2007). 10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.342-343.813 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H.-J., Chen J., Karageorgiou V., Altman G. H., and Kaplan D. L., Biomaterials 25, 1039 (2004). 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00609-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H. J., Fridrikh S. V., Rutledge G. C., and Kaplan D. L., Biomacromolecules 5, 786 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva S. S., Maniglio D., Motta A., Mano J. F., Reis R. L., and Migliaresi C., Macromol. Biosci. 8, 766 (2008). 10.1002/mabi.200700300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara Y., Nakayama A., Matsumura N., Yoshioka T., and Tsuji M., J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 107, 3681 (2008). 10.1002/app.27539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Vepari C., Jin H.-J., Kim H. J., and Kaplan D. L., Biomaterials 27, 3115 (2006). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min B.-M., Jeong L., Lee K. Y., and Park W. H., Macromol. Biosci. 6, 285 (2006). 10.1002/mabi.200500246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min B.-M., Lee G., Kim S. H., Nam Y. S., Lee T. S., and Park W. H., Biomaterials 25, 1289 (2004). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukigara S., Gandhi M., Ayutesede J., Micklus M., and Ko F., Polymer 44, 5721 (2003). 10.1016/S0032-3861(03)00532-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sukigara S., Gandhi M., Ayutesede J.,Micklus M., and Ko F., Polymer 45, 3701 (2004). 10.1016/j.polymer.2004.03.059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M., Jin H. J., Kaplan D. L., and Rutledge G. C., Macromolecules 37, 6856 (2004). 10.1021/ma048988v [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Zhang Y., Wang H., Yin G., and Dong Z., Biomacromolecules 10, 2240 (2009). 10.1021/bm900416b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkoob S., Eby R. K., Reneker D. H., Hudson S. D., Ertley D., and Adams W. W., Polymer 45, 3973 (2004). 10.1016/j.polymer.2003.10.102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkoob S., Reneker D. H., Ertley D.,Eby R. K., and Hudson S. D. thesis, The University of Akron, 1998, Vol. Doctor of Philosophy, p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Zarkoob S., Reneker D. H., Ertley D., Eby R. K., and Hudson S. D., U.S. Patent No. 6,110,590 (August 29 2000).

- Zhang K., Mo X., Huang C., He C., and Wang H., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 93A, 976 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Baughman C. B., and Kaplan D. L., Biomaterials 29, 2217 (2008). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J., Cao C., and Ma X., Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 45, 504 (2009). 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2009.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus M. C., Boland E. D., Koo H. P., Barnes C. P., Pawlowski K. J., Wnek G. E., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., Acta Biomater. 2, 19 (2006). 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus M. C., Boland E. D., Simpson D. G., Barnes C. P., and Bowlin G. L., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 81A, 299 (2007). 10.1002/jbm.a.30989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S., Barnes C., Simpson D., and Bowlin G., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 85A, 115 (2008). 10.1002/jbm.a.31556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S. A., Francis M. P., Garg K., McClure M. J., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., Biomed. Mater. 3, 045001 (2008). 10.1088/1748-6041/3/4/045001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus M., Boland E., Sell S., Bowen W., Koo H., Simpson D., and Bowlin G., Biomed. Mater. 2, 257 (2007). 10.1088/1748-6041/2/4/008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wnek G. E., Carr M. E., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., Nano Lett. 3, 213 (2003). 10.1021/nl025866c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C. P., Smith M. J., Bowlin G. L.,Sell S. A., Tang T., Matthews J. A., Simpson D. G., and Nimtz J. C.Journal of Engineered Fibers and Fabrics 1, 16 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Rayleigh L., Philos. Mag. 14, 184 (1882). [Google Scholar]

- Zeleny J., Phys. Rev. 10, 1 (1917). 10.1103/PhysRev.10.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacDiarmid A. G., W. E.Jones, Jr., Norris I. D. Gao J., A. T.Johnson, Jr., Pinto N. J., Hone J., Han B., Ko F. K., Okuzaki H., and Llaguno M., Synth. Met. 119, 27 (2001). 10.1016/S0379-6779(00)00597-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larrondo L. and Manley M. S. J., J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Phys. Ed. 19, 909 (1981). 10.1002/pol.1981.180190601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larrondo L. and Manley M. S. J., J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Phys. Ed. 19, 921 (1981). 10.1002/pol.1981.180190602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larrondo L. and Manley M. S. J., J. Polym. Sci., Polym. Phys. Ed. 19, 933 (1981). 10.1002/pol.1981.180190603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yarin A. L., Koombhongse S., and Reneker D. H., J. Appl. Phys. 90, 4836 (2001). 10.1063/1.1408260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koombhongse S., Ph.D. thesis, University of Akron, 2001). [Google Scholar]

- Deitzel J. M., Krauthauser C., D.HarrisP.C., and Kleinmeyer J., in Polymeric Nanofibers, ACS Symposium Series, edited by Reneker D. H. and Fong H. (American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, 2006), Vol. 918. 10.1021/bk-2006-0918.ch005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koombhongse S., Liu W., and Reneker D. H., J. Polym. Sci. 39, 2598 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Reneker D. H. and Fong H., Polymeric Nanofibers (American Chemical Society, Washington DC, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- Shin M., Hohman M. M., Brenner M. P., and Rutledge G. C., Polymer 42, 9955 (2001). 10.1016/S0032-3861(01)00540-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demir M. M., Yilgor I., Yilgor E., and Erman B., Polymer 43, 3303 (2002). 10.1016/S0032-3861(02)00136-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pham Q. P., Sharma U., and Mikos A. G., Tissue Eng. 12, 1197 (2006). 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong X., Kim K., Fang D., Ran S., Hsiao B. S., and Chu B., Polymer 43, 4403 (2002). 10.1016/S0032-3861(02)00275-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fong H., Chun I., and Reneker D. H., Polymer 40, 4585 (1999). 10.1016/S0032-3861(99)00068-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. X., Yuan X. Y., Wu L. L., Han Y., and Sheng J., Eur. Polym. J. 41, 423 (2005). 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2004.10.027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang D., Hsiao B. S., and Chu B., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 59, 1392 (2007). 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker B. M., Gee A. O., Metter R. B., Nathan S., Marklein R. A., Burdick J. A., and Mauck R. L., Biomaterials 29, 2348 (2008). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.01.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acatay K., Simsek E., Ow-Yang C., and Menceloglu Y. Z., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 43, 5210 (2004). 10.1002/anie.200461092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao K., Hu X., Dai C., and Yi T., Mater. Sci. Eng., B 131, 100 (2006). 10.1016/j.mseb.2006.03.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens J. S., Chase D. B., and Rabolt J. F., Macromolecules 37, 877 (2004). 10.1021/ma0351569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner A. and Wendoeff J. H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 46, 5670 (2007). 10.1002/anie.200604646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Zussman E., Yarin A. L., Wendorff J. H., and Greiner A., Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 15, 1929 (2003). 10.1002/adma.200305136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han X. J., Huang Z., He C., and Liu L., High Perform. Polym. 19, 147 (2007). 10.1177/0954008306072499 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li D. and Xia Y., Nano Lett. 4, 933 (2004b). 10.1021/nl049590f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. H., Fridrikh S. V., and Rutledge G. C., Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 16, 1582 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Kidoaki S., Kwon I. K., and Matsuda T., Biomaterials 26, 37 (2005). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz C. M., van Tuijl S., Bouten C. V. C., and Baaijens F. P. T., Acta Biomater. 1, 575 (2005). 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Shah J. D., and Wang H., Tissue Eng Part A 15, 945 (2009). 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas V., Zhang X., Catledge S. A., and Vohra Y. K., Biomed. Mater. 2, 224 (2007). 10.1088/1748-6041/2/4/004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telemeco T. A., Ayres C., Bowlin G. L., Wnek G. E., Boland E. D., Cohen N., Baumgarten C. M., Mathews J., and Simpson D. G., Acta Biomater. 1, 377 (2005). 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um I. C., Fang D., Hsiao B. S., Okamoto A., and Chu B., Biomacromolecules 5, 1428 (2004). 10.1021/bm034539b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jha B. S., Colello R. J., Bowman J. R., Sell S. A., Lee K. D., Bigbee J. W., Bowlin G. L., Chow W. N., Mathern B. E., and Simpson D. G., Acta Biomater. 7, 203 (2010). 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashammakhi N., Ndreu A., Yang Y., Ylikauppila H., Nikkola L., and Hasirci V., J. Craniofac Surg. 18, 3 (2007). 10.1097/01.scs.0000236444.05345.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland E. D., Telemeco T. A., Simpson D. G., Wnek G. E., and Bowlin G. L., J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part B: Appl. Biomater. 71B, 144 (2004). 10.1002/jbm.b.30105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattarai S. R., Bhattarai N., Yi H. K., Hwang P. H., Cha D. I., and Kim H. Y. Biomaterials 25, 2595 (2004). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. H., Shin H. J., Cho I. H., Kang Y.-M., Kim I. A., Park K.-D., and Shin J.-W., Biomaterials 26, 1261 (2005). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S. A., Wolfe P. S., Garg K., McCool J. M., Rodriguez I. A., and Bowlin G. L., Polymer 2, 522 (2010). 10.3390/polym2040522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kolacna L., Bakesova J., Varga F., Kostakova E., Planka L., Necas A., Lukas D., Amler E., and Pelouch V., Physiol. Res. 56, S51 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C. P., Sell S. A., Boland E. D., Simpson D. G., and Bowlin G. L., Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 59, 1413 (2007). 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccafoschi F., Habermehl J., Vesentini S., and Mantovani D., Biomaterials 26, 7410 (2005). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z. G., Wang P. W., Wei B., Mo X. M., and Cui F. Z., Acta Biomater. 6, 372 (2010). 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W., Ma Z., Yong T., Teo W. E., and Ramakrishna S., Biomaterials 26, 7606 (2005). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S. I., Kim S. Y., Cho S. K., Chong M. S., Kim K. S., Kim H., Lee S. B., and Lee Y. M., Biomaterials 28, 1115 (2007). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aszódi A., Legate K. R., Nakchbandi I., and Fässler R., Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22, 591 (2006). 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daamen W. F., van Moerkerk H. T. B., Hafmans T., Buttafoco L., Poot A. A., Veerkamp J. H., and van Kuppevelt T. H., Biomaterials 24, 4001 (2003). 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00273-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafemann B., Ensslen S., Erdmann C., Niedballa R., Zühlke A., Ghofrani K., and Kirkpatrick C. J., Burns 25, 373 (1999). 10.1016/S0305-4179(98)00162-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Y.-R., Chen C.-N., Tsai S.-W., Wang Y. J., and Lee O. K., Stem Cells 24, 2391 (2006). 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. W., Song J. H., and Kim H. E., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 79A, 698 (2006). 10.1002/jbm.a.30848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman E., Livesay G. A., Dee K. C., and Nauman E. A., Ann. Biomed. Eng. 34, 726 (2006). 10.1007/s10439-005-9058-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura Y., Hokugo A., Takamoto T., Tabata Y., and Kurosawa H., Tissue Eng. 14, 47 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglund J. D., Nerem R. M., and Sambanis A., Tissue Eng. 10, 1526 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijtenhuijs P., Buttafoco L., Poot A. A., Daamen W. F., van Kuppevelt T. H., Dijkstra P. J., de Vos R. A. I., Sterk L. M. Th., Geelkerken B. R. H., Feijen J., and Vermes I., Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 39, 141 (2004). 10.1042/BA20030105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland E. D., Espy P. G., and Bowlin G. L., Encyclopedia of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, 2004, p. 1.

- Altman G. H., Horan R. L., Lu H. H., Moreau J., Martin I., Richmond J. C., and Kaplan D. L., Biomaterials 23, 4131 (2002). 10.1016/S0142-9612(02)00156-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H., Liu H., Toh S. L., and Goh J. C. H., Biomaterials 29, 1017 (2008). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan H., Liu H., Wong E. J. W., Toh S. L., and Goh J. C.H., Biomaterials 29, 3324 (2008). 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Ge Z., Wang Y., Toh S. L., Sutthikkum V., and Goh J. C. H., J. Biomed. Mater. Res., Part B: Appl. Biomater. 10, 129 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S. A., Biomedical Engineering (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, 2009), p. 322. [Google Scholar]

- Seo Y.-K., Choi G.-M., Kwon S.-Y., Lee H. S., Park Y. S., Song K. Y., Kim Y. J., and Park J. K., Key Eng. Mater. 342–343, 73 (2007). 10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.342-343.73 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toh S. L., Teh T. K. H., Vallaya S., and Goh J. C. H., Key Eng. Mater. 326–328, 727 (2006). 10.4028/www.scientific.net/KEM.326-328.727 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soffer L., Wang X., Zhang X., Kluge J., Dorfmann L., Kaplan D. L., and Leisk G., J. Biomater. Sci., Polym. Ed. 19, 653 (2008). 10.1163/156856208784089607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinel L., Karageorgiou V., Hofmann S., Fajardo R., Snyder B., Li C., Zichner L., Langer R., Vunjak-Novakovic G., and Kaplan D. L., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 71A, 25 (2004). 10.1002/jbm.a.30117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayres C., Jha B., Sell S., Bowlin G., and Simpson D., Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine 2, 20 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell S., Barnes C. P., Smith M., McClure M., Madurantakam P., Grant J., McManus M., and Bowlin G., Polym. Int. 56, 1349 (2007). 10.1002/pi.2344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumbar S. G., James R., Nukavarapu S. P., and Laurencin C. T., Biomed. Mater. 3, 034002 (2008). 10.1088/1748-6041/3/3/034002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenawy E.-R., Bowlin G. L., Mansfield K., Layman J., Simpson D. G., Sanders E. H., and Wnek G. E., J. Controlled Release 81, 57 (2002). 10.1016/S0168-3659(02)00041-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Luu Y. K., Chang C., Fang D., Hsiao B. S., Chu B., and Hadjiargyrou M., J. Controlled Release 98, 47 (2004). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J., Xu X., Chen X., Liang Q., Bian X., Yang L., and Jing X., J. Controlled Release 92, 227 (2003). 10.1016/S0168-3659(03)00372-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J., Yang L., Liang Q., Zhang X., Guan H., Xu X., Chen X., and Jing X., J. Controlled Release 105, 43 (2005). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.02.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Yang L., Xu X., Wang X., Chen X., Liang Q., Zeng J., and Jing X., J. Controlled Release 108, 33 (2005). 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z.-M., He C.-L., Yang A., Zhang Y., Han X.-J., Yin J., and Wu Q., J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 77A, 169 (2006). 10.1002/jbm.a.30564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chunder A., Sarkar S., Yu Y., and Zhai L., Colloids Surf., B 58, 172 (2007). 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]