Summary

Background and objectives

This study was undertaken by the American Association of Kidney Patients (AAKP) to better understand ESRD patients' satisfaction with their current renal replacement therapy (RRT) and the education they received before initiating therapy.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

In addition to an open invitation on the AAKP website, nearly 9000 ESRD patients received invitations to complete the survey, which consisted of 46 questions. Satisfaction was measured on a 1 (extremely dissatisfied) to 7 (extremely satisfied) scale.

Results

Survey respondents were younger, more highly educated, and more likely to be white as well as employed as compared with the U.S. dialysis population. A total of 977 patients responded. Overall patient satisfaction with current RRT treatment varied from a low of 4.5 for in-center hemodialysis (ICHD) to a high of 6.1 in transplant (TX) patients. Peritoneal dialysis (PD) and home hemodialysis (HHD) mean scores were 5.2 and 5.5, respectively. PD, HHD, and TX patients' satisfaction scores were significantly higher than those of ICHD patients (P < 0.05). Approximately 31% of respondents felt that the therapies were not equally and fairly presented as treatment options, and 32% responded that they were not educated regarding HHD.

Conclusions

ESRD patients are not uniformly advised about all possible treatment methods and hence were only moderately satisfied with their pretreatment education. Once on RRT, those on a home therapy or with a kidney TX are more satisfied than those with ICHD.

Introduction

This project was designed to help clinicians meet the challenge of improving the patient education experience, thereby improving outcomes. Our main study objective was to better understand patient satisfaction with the scope and quality of dialysis education received before beginning renal replacement therapy (RRT) as well as with their current therapy. A second goal was to gain insight into the factors (including education) that influenced the choice of their RRT.

Education plays a key role in helping patients adjust to their kidney disease, but many individuals remain uninformed about the effect that RRT will have upon their lives. Mehrotra found that most pre-ESRD patients have a lack of knowledge regarding RRT options (1). Other studies have found similar results (2–4). Poor adherence to diet, medications, and treatment schedules may be the result of ineffective or unavailable education efforts (5). Additionally, education might permit better-informed decisions about dialysis access and the issues patients face when they require ESRD care (6). Optimally, education could reduce the ‘urgent starts‘ that lead to increased morbidity, mortality, and costs as therapy is initiated (7,8).

In a survey of dialysis patients, 30% reported that dialysis treatment options were not presented to them until after starting dialysis, and 48% were not presented treatment options until after dialysis or <1 month before starting dialysis (1). Interestingly, 84% were told about in-center hemodialysis (ICHD), but only 34% and 12% were told about peritoneal dialysis (PD) and home hemodialysis (HHD), respectively. In a more recent study of stage 3 through stage 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients, <50% had any knowledge of PD (3).

Even among patients aware of their disease, inadequate BP control, lack of arteriovenous fistula or PD catheter planning, or consideration of preemptive transplantation reflect insufficient knowledge of risks, benefits, and alternatives in decisions about treatment options (9–11).

Materials and Methods

The Survey

The online survey was available from June 17 through July 2, 2008. Nearly 9000 ESRD patients from the American Association of Kidney Patient's (AAKP) patient member database received e-mail invitations from AAKP in which they were directed to access the survey online (http://www.aakp.org). The average reading level of the survey was ninth grade, and the targeted time to complete the survey was 30 minutes. Participants could also enroll without receiving an e-mail invitation by directly accessing the AAKP website during the survey administration period. Rollout of the survey was accompanied by press and media releases.

The survey consisted of 46 questions including demographic information, current and past modality use, satisfaction with current treatment, satisfaction with education offered before starting therapy, objectivity of education, factors influencing choice of therapy, the occurrence and usefulness of information, and interest in additional training and education. The survey defined education/training as “information provided about dialysis choice options including treatment location, treatment schedule, infection complications, diet restrictions, physician visits, etc.” This definition clearly focuses on education rather than training. Survey questions were posted on the AAKP website.

The survey was analyzed to determine the frequency and the value of an educational episode to define areas needing improvement. Survey items were rated on a seven-point scale in which 1 indicated ‘never‘ and 7 indicated ‘constantly‘ for frequency and in which 1 indicated ‘not at all helpful‘ and 7 indicated ‘extremely helpful‘ for value of an educational episode. Additionally, the frequency and value scores were multiplied to determine the intensity of each item. Satisfaction was measured on a seven-point scale with 1 being ‘extremely dissatisfied‘ and 7 being ‘extremely satisfied.‘

Data integrity was limited because personal access codes were not required to take the survey and no patient identifying information was included in the survey. t tests were used to examine differences in mean scores between dialysis modalities and the Z test was used for differences in proportions. We consider a P value <0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

Patient Information

A total of 977 participants answered the survey and provided demographic data on RRT (Table 1).Of these participants, 821 (84%) were ESRD patients themselves and 156 (16%) were caretakers of patients with ESRD. We pooled the data from patients and caretakers because the results between the two groups were similar. The survey patient population, as compared with the total 2007 U.S. ESRD population, was younger (25% ≥66 years versus 36% ≥65 years), more often female (50% versus 44%), more likely to be white (79% versus 61%), and more likely to be employed (52% versus 36%).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Demographics | Current RRT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICHD Patients | PD Patients | HHD Patients | TX Patients | All (ESRD) Patients | |

| Sample size (% of ESRD) | 369 (38) | 100 (10) | 53 (5) | 455 (47) | 977 (100) |

| Percent of dialysis | 70.7% | 19.2% | 10.2% | ||

| Age category | |||||

| <18 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 7 (1.5) | 9 (0.9) |

| 18 to 39 | 30 (8.1) | 18 (18.0) | 5 (9.4) | 64 (14.1) | 117 (12.0) |

| 40 to 65 | 199 (53.9) | 56 (56.0) | 35 (66.0) | 314 (69.2) | 604 (61.9) |

| 66 and older | 137 (37.1) | 25 (25.0) | 13 (24.5) | 68 (15.0) | 243 (24.9) |

| missing | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.3) |

| Gender (% male) | 57.34% | 56.0% | 47.2% | 43.2% | 50.1% |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| white | 273 (74.0) | 79 (79.0) | 43 (81.1) | 376 (82.6) | 771 (78.9) |

| black | 52 (14.1) | 9 (9.0) | 4 (7.6) | 26 (5.7) | 91 (9.3) |

| Hispanic | 22 (6.0) | 5 (5.0) | 2 (3.8) | 17 (3.7) | 46 (4.7) |

| American Indian | 2 (0.5) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.9) | 3 (0.7) | 7 (0.7) |

| Asian | 13 (3.5) | 2 (2.0) | 1 (1.9) | 22 (4.8) | 38 (3.9) |

| other/unknown | 7 (1.9) | 4 (4.0) | 2 (3.8) | 11 (2.4) | 24 (2.5) |

| Education | |||||

| <high school | 20 (5.4) | 4 (4.0) | 1 (1.9) | 11 (2.4) | 36 (3.7) |

| high school | 72 (19.5) | 18 (18.0) | 6 (11.3) | 62 (13.6) | 158 (16.2) |

| some college | 123 (33.3) | 26 (26.0) | 13 (24.5) | 106 (23.3) | 268 (27.4) |

| college degree | 84 (22.8) | 28 (28.0) | 18 (34.0) | 169 (37.1) | 299 (30.6) |

| advanced degree | 65 (17.6) | 24 (24.0) | 13 (24.5) | 106 (23.3) | 208 (21.3) |

| missing | 5 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.8) | 1 (0.2) | 8 (0.8) |

| Employment | |||||

| employed full time | 52 (14.1) | 27 (27.0) | 8 (15.1) | 180 (39.6) | 267 (27.3) |

| employed part time | 30 (8.1) | 9 (9.0) | 10 (18.9) | 45 (9.9) | 94 (9.6) |

| unable to work | 92 (24.9) | 21 (21.0) | 14 (26.4) | 2 (0.4) | 129 (13.2) |

| retired | 177 (48.0) | 36 (36.0) | 17 (32.1) | 128 (28.1) | 358 (36.6) |

| other or missing | 18 (4.9) | 7 (7.0) | 4 (7.6) | 100 (22.0) | 129 (13.2) |

| Time on current therapy (years) | |||||

| <2 | 179 (48.5) | 71 (71.0) | 24 (45.3) | 144 (31.6) | 418 (42.8) |

| 2 to 6 | 138 (37.4) | 25 (25.0) | 24 (45.3) | 160 (35.2) | 347 (35.5) |

| 7 to 12 | 23 (6.2) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 81 (17.8) | 105 (10.7) |

| >12 | 16 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.6) | 61 (13.4) | 80 (8.2) |

| not known/missing | 13 (3.6) | 3 (3.0) | 2 (3.8) | 9 (2.0) | 27 (2.8) |

Data presented as n (percent) unless otherwise indicated.

ICHD patients tended to be older, male, black or Hispanic, less educated, and not employed compared with patients treated with other modalities. Those who had received a kidney transplant (TX) tended to be on their therapy the longest. Of PD patients, 81% were on continuous cycling PD and 19% were on continuous ambulatory PD. For HHD, 23% were on nocturnal, 65% were on short daily, and 12% were on conventional three-times-weekly HHD.

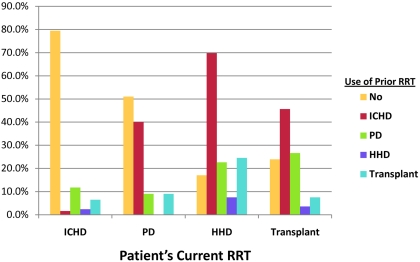

Many patients had experienced more than one form of RRT (Figure 1). However, nearly 80% of ICHD patients had never used another modality compared with just over 50% of PD patients. Seventy percent of HHD and 40% of PD patients had been treated with ICHD before starting HHD or PD, respectively.

Figure 1.

Prior use of other RRTs.

Satisfaction with Current Therapy and Education

Overall patient satisfaction with current RRT varies from a low of 4.5 for ICHD patients to a high of 6.1 in TX patients (Table 2). The mean scores for the home-based PD and HHD therapies as well as TX patients are significantly higher those of ICHD patients (P < 0.05). TX patients are more satisfied with their treatment than PD or HHD patients (P < 0.05). Satisfaction with education mirrored the degree of satisfaction with treatment modality within each treatment group. Table 2 provides scores for satisfaction with education before starting RRT. These were 5.0, 5.4, 5.2, and 5.6 for ICHD, PD, HHD and TX, respectively. With respect to the education ratings by a patient's current treatment, TX patients ranked their satisfaction with education across the four modalities the highest whereas ICHD patients ranked it the lowest with PD and HHD patients in between. In all cases except ICHD, satisfaction was highest for the modality that the patient selected. HHD patients were least satisfied (4.7) with education regarding TX.

Table 2.

Patient satisfaction with dialysis treatment and with treatment education

| Satisfaction Measures | Mean Rating of Patient's Current RRT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICHD | PD | HHD | TX | ESRD | |

| Overall satisfaction with current RRT | 4.5 (5) | 5.2 (6)a,b | 5.5 (6)a,b | 6.1 (7)a | 5.4 (6) |

| Satisfaction with ICHD education before starting initial RRT | 4.8 (5)b | 4.8 (5)b | 4.8 (5) | 5.2 (5) | 5.0 (5) |

| Satisfaction with PD education before starting initial RRT | 4.9 (5) | 5.8 (7)a | 5.0 (5) | 5.5 (6) | 5.4 (6) |

| Satisfaction with HHD education before starting initial RRT | 4.9 (5)b | 5.2 (6) | 5.5 (6) | 5.4 (5) | 5.2 (5) |

| Satisfaction with TX education before starting initial RRT | 5.2 (6)b | 5.5 (6) | 4.7 (5)b,c | 5.9 (6) | 5.6 (6) |

Ratings of 1 to 7, with a rating of 1 indicating being extremely dissatisfied and a rating of 7 indicating being extremely satisfied.

Mean score is statistically significantly (P < 0.05, minimum) different than aICHD,

TX, and

PD.

Table 3 shows whether patients were provided specific modality education before selecting their initial therapy. It breaks the data into columns on the basis of the modality. The last column, ESRD, is an overall percentage of all scores. Note that according to the survey, 69.7% of ESRD patients received ICHD education/training, but only 58.2% and 31.6% were told about PD and HHD, respectively. Patients were best educated about the therapy they selected; 71.3% of ICHD patients were educated about ICHD, 87% of PD patients about PD, and 81.1% of TX patients were educated about TX. The exception was HHD, in which only 41.5% were educated about this modality before selecting their therapy. Also, note that only 47.2% of patients whose current therapy is ICHD were educated about a TX.

Table 3.

Percent of patients who were provided specific modality education/training before selecting therapy

| Patient's Current RRT (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICHD | PD | HHD | TX | ESRD | |

| ICHD education or training | 71.3 | 67.0 | 81.1 | 67.7 | 69.7 |

| PD education/training | 48.0 | 87.0 | 45.3 | 61.8 | 58.2 |

| HHD education/training | 34.1 | 25.0 | 41.5 | 29.9 | 31.6 |

| TX education/training | 47.2 | 58.0 | 64.2 | 81.1 | 65.0 |

Modality Education

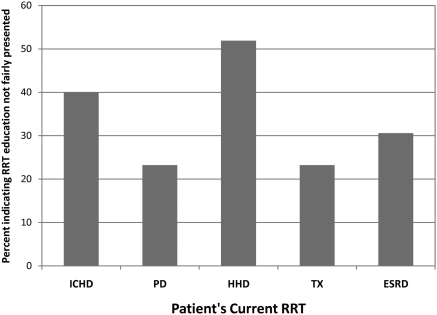

Many patients felt that all modalities were not presented equally and fairly during the initial CKD education (Figure 2). For example, 52% of HHD patients and 23% of TX and PD patients felt that all modalities were not presented equally and fairly during RRT education. Of ICHD patients, 40% did not feel modality education choices were fairly presented.

Figure 2.

Percent of patients indicating that RRT modalities were not presented equally or fairly.

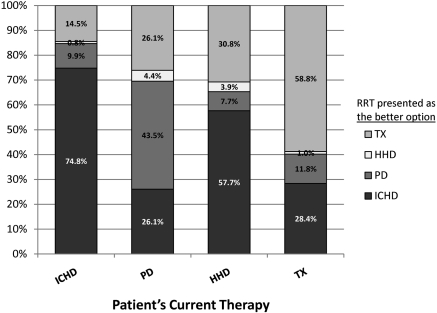

Figure 3 provides information on which therapy was presented as the better option to each group of patients. HHD was rarely presented as the better option to any of the groups. Only 3.9% of HHD patients reported that HHD was presented as the best option. ICHD was presented as the best option for ICHD, HHD, and TX patients more often than any other treatment. Most RRT education occurred in the doctor's office and was provided by the physician or nurse, although education did occur at other sites (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Percent of patients indicating which RRT was presented as the better option.

Table 4.

Where or who provided the RRT education

| Specific RRT Education | Patient's Current RRT (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICHD | PD | HHD | TX | |

| Where or who provided ICHD education | ||||

| doctor's office, by a doctor or nurse | 48.3 | 53.7 | 44.2 | 47.7 |

| hospital | 23.4 | 14.9 | 20.9 | 24.0 |

| other | 27.2 | 29.9 | 32.6 | 27.6 |

| do not know | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| Where or who provided the PD education | ||||

| doctor's office, by a doctor or nurse | 50.0 | 67.8 | 66.7 | 57.5 |

| hospital | 19.9 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 13.0 |

| other | 29.0 | 28.7 | 29.1 | 28.8 |

| do not know | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | 0.7 |

| Where or who provided the HHD education | ||||

| doctor's office, by a doctor or nurse | 48.0 | 44.0 | 28.6 | 48.9 |

| hospital | 19.2 | 12.0 | 28.6 | 17.3 |

| other | 31.2 | 44.0 | 42.8 | 31.6 |

| do not know | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 |

| Where or who provided the TX education | ||||

| doctor's office, by a doctor or nurse | 47.4 | 58.6 | 42.4 | 49.5 |

| hospital | 37.0 | 24.1 | 36.4 | 38.9 |

| other | 14.5 | 17.3 | 21.2 | 11.1 |

| do not know | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 |

Factors Affecting Choice of Therapy

The most important influencer for patients deciding on choice of therapy varied between modalities (Table 5). Physician recommendation was the most influential reason for ICHD and TX patients. PD and HHD patients ranked the “desire to manage their own care” (67% and 79%, respectively) or “desire to stay at home” (55% and 66%, respectively) as their primary reason for selecting their RRT. TX patients also ranked “desire to manage their own care” as influential in their decision.

Table 5.

Top three most important items that influenced the decision to choose the current RRT

| Items Influencing Choice of RRT | Patient's Current RRT (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICHD | PD | HHD | TX | ESRD | |

| Doctor recommendation | 65.6 | 38.0 | – | 65.7 | 60.2 |

| Desire to be taken care of by clinicians | 40.4 | – | – | – | – |

| Desire to stay at home | – | 55.0 | 66.0 | – | – |

| Desire to manage own care | – | 67.0 | 79.2 | 44.6 | 33.7 |

| Location/travel to dialysis center | 26.6 | – | – | – | – |

| Ability to travel | – | – | – | 29.0 | – |

| Dialysis education received | – | – | 22.6 | – | – |

| Other | – | – | 22.6 | – | 21.1 |

Topics Selected as Being of the Most Interest to the Patient

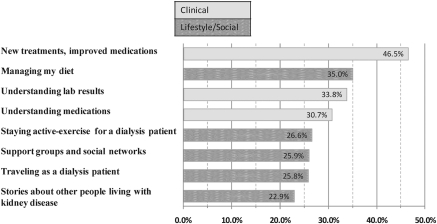

Topics selected as having the most interest to the survey respondents seemed to be clinical rather than lifestyle in nature (Figure 4). These included new treatments, improved medications, understanding laboratory results, and understanding medications. The lifestyle topic rated highest was ‘managing my diet.‘ Topics of less interest were staying active-exercise for a dialysis patient, support groups and social networks, traveling as a dialysis patient, and stories about other people living with kidney disease. Patients in each of the four subgroups tended to select these clinical and lifestyle topics in similar order.

Figure 4.

Topics selected as being of the most interest to the patient categorized as clinical or lifestyle/social.

Frequency and Helpfulness of Key Questions of the Education/Training

Table 6 provides the results of how the respondents ranked the helpfulness of an item compared with the frequency at which it occurred before beginning their therapy. Patients consistently ranked how helpful an item was higher than the frequency at which it actually occurred. This suggests respondents do not get the opportunity to ask personal questions because this item had the largest gap between helpfulness and frequency. The most helpful item overall was ‘I was given equal amounts of information about PD and ICHD‘ followed by ‘a dialysis nurse met with me.‘ The other two items that stood out as important or helpful were ‘I had a chance to ask my personal questions‘ and ‘I was given information about my diet and medication.‘ There was minor variation across therapies on the helpfulness of each item.

Table 6.

Frequency and helpfulness of key questions of the education/training

| Questions | Mean Scores |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICHD Patients |

PD Patients |

HHD Patients |

TX Patients |

|||||||||

| Often | Helpful | Intensity | Often | Helpful | Intensity | Often | Helpful | Intensity | Often | Helpful | Intensity | |

| I received personal attention from my doctor | 4.0 | 4.9 | 22.3 | 5.4 | 5.8 | 33.6 | 3.6 | 5.2 | 20.8 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 26.2 |

| I was given equal amounts of information about PD and HD | 5.4 | 5.9 | 33.6 | 6.3 | 6.5 | 41.8 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 37.0 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 41.2 |

| I had a chance to ask my personal questions | 4.4 | 5.6 | 26.7 | 5.9 | 6.5 | 40.0 | 4.7 | 6.0 | 30.8 | 4.8 | 5.7 | 31.0 |

| A dialysis nurse met with me | 5.4 | 6.0 | 33.6 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 39.2 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 35.0 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 39.7 |

| I was given information about my diet and medication | 4.8 | 5.5 | 29.2 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 37.9 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 28.9 | 5.9 | 6.2 | 38.0 |

| The doctor and nurse explained my blood pressure to me | 2.7 | 3.7 | 13.9 | 3.6 | 4.2 | 20.9 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 20.4 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 26.1 |

| There was a discussion about staying employed | 2.8 | 3.8 | 14.8 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 21.6 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 18.4 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 26.1 |

Discussion

The AAKP sought to define various aspects of modality education as experienced by patients. Results confirm, as in other reports, that improvements are necessary. Previously, Finkelstein reported the disturbing observation from a self-administered questionnaire that one third of CKD stage 3 to 5 patients had limited or no understanding of their kidney disease despite having visited a nephrologist at least 4 times, and only half had an understanding of dialysis modalities or transplantation (3).

Focus groups discussing education programs often reveal considerable consumer confusion about requisite components of an effective program (12). This survey points out that patients were quite clear regarding their expectations. Although physician recommendations about care were valued, patients often indicated that education about all modalities had not been sufficient. This survey also shows that most patients consider physicians the most valued resource for information. These findings strongly suggest that nephrologists and the renal community develop strategies that more effectively and objectively deliver unbiased education about all modalities to all CKD patients.

Choice of Therapy

Patient demographics and external influences such as physician recommendation and expected lifestyle seem to affect how patients choose a therapy. This survey corroborates the key notion that working, active, and mobile persons are most likely to be involved in their own care and decision-making. Patients selecting ICHD were more likely to subsequently choose another modality although education on home therapies is less likely to be delivered to them as members of the in-center population. This suggests that introducing all modalities during stage 4 and continuing efforts during in-center treatment might favorably affect patient satisfaction and subsequent choice, especially in light of the benefit of home therapies (13,14). However, this survey lacked the ability to separate physician bias toward a given modality from their valid assessment of the patient's suitability because of clinical, psychosocial, or practical reasons. For example, as shown in Figure 3, only 3.9% of HHD patients were presented HHD as their best option. This may be due to the lack of a suitable home environment or a limited number of facilities with HHD expertise.

Persons who prefer the security of more monitored treatment seem to prefer in-center dialysis care. Patients who harbor a desire for independence may have realistic barriers to dialysis at home that should be acknowledged. Legitimate concerns need not preclude education for these patients about novel and creative choices such as in-center nocturnal dialysis, which offers the ability to independently dialyze within a protective environment that provides adequate supervision.

It should be noted that several studies have found increased satisfaction with home therapies as compared with ICHD (15–17). For instance, Rubin and colleagues found that PD patients were much more likely than ICHD patients to rate their dialysis care as excellent (16).

Education Process

The survey disclosed a general patient preference for physician-based education because 60.2% of respondents felt the most valued resource for information was the physician. Such a preference does not discount the abilities of other professionals to make important contributions to comprehensive patient education as CKD progresses. Given the results of our survey that current education is not being done satisfactorily, we need studies to help us understand how to better provide education to late stage 3 and stage 4 CKD patients. The Medicare Improvement for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 contains a provision to reimburse these efforts, and curricula and teaching tools can facilitate office-based patient education (18).

The two most influential items among the home-based therapies (PD and HHD) were “desire to manage their own care” and “desire to stay at home.” TX patients also ranked “desire to manage their own care” as influential in their therapy decision. On the basis of these results, education should focus on new treatments and medications, followed by diet management and understanding laboratory results. Patients appear less interested in exercise, support groups, travel, and stories about other people living with kidney disease. These results may be an artifact of the inherent bias of the survey toward more Internet savvy and hence more educated patients.

Although it appears that physician-based education is needed to satisfy and inform patients, time constraints of nephrologists will require a better understanding of how best to communicate with patients. In Table 4, a range of 27% to 44% of respondents indicated that “other” sources were utilized. Alternative high-quality sources of information should also be available to ESRD patients.

Work Status

Only 14% and 15% of ICHD and HHD respondents, respectively, were fully employed, yet only 25% to 26% of this admittedly biased survey population indicated that they were unable to work. TX recipients (40%) and PD patients (27%) represented the largest proportions of employed patients. These responses collectively suggest that work potential may be practically restricted by the time constraints linked to ICHD. Accordingly, one might expect to see a corollary trend toward increased employment of patients facilitated by growth of after-hours dialysis. However, it is difficult to reconcile the low rate of reported employment among home dialysis respondents given that these patients often have the flexibility to perform dialysis after hours. Other factors such as energy level and compensation considerations (e.g., availability of insurance) that were not included in this survey should be explored.

Use of the Internet

Reliance on the Internet to conduct this survey created a bias against those lacking access to the Web and those without the requisite computer skills or physical capacity to use the Internet. That patients with relatively lower education levels and restricted access to the Internet were undersampled is an intrinsic weakness of any Web-based survey, and generalization of results to the broader population must be carefully considered. Participating dialysis patients were relatively well informed and educated, with a disproportionately high representation of TX recipients among the respondents. However, it is our belief that the results and conclusions in this paper are consistent with those in the literature, which supports their validity and usefulness to the overall population.

The Internet is a highly useful mechanism to promote patient education and should continue to be utilized (19). In 2006, Schatell et al. published an assessment of ICHD patient use of Web-based services using a widely distributed survey that canvassed the United States and included responses from 1804 patients (20). They discovered that the Internet was used for health information by 43.5% of patients by themselves or with assistance from others, but that users tended to be relatively highly educated. Most important was their identification of the reason for not using the Internet as being a lack of availability (70.4%) rather than a lack of interest (21.3%). It would seem that dialysis centers and physician offices might well serve patients by placing Internet resources in waiting rooms and lobbies. Patients who do not use the Internet or who have poor computer skills will still need printed materials or other audiovisual aids.

Frequency and Helpfulness of Education/Training

Respondents consistently ranked the helpfulness of an item higher than the frequency at which it occurred, indicating that there is a gap between the education they should have received and what they actually received. Additionally, it shows the desire of patients to understand their disease and the treatment alternatives, to become involved in their own care, and to understand details beyond what is possibly being offered by clinicians.

The topic least discussed was staying employed, especially among ICHD patients. There are potential reasons why ICHD patients ranked staying employed so low, including difficulty in coordinating work and their dialysis schedule.

In conclusion, this online survey focused on the perceptions of ESRD patients about education they had received regarding treatment choices. There is a moderate to high level of satisfaction with current therapies, although TX and home-based therapies of PD and HHD provided higher levels of satisfaction than ICHD. Satisfaction with the education/training received before initial therapy was moderate, leaving room for improvement. Clinicians, including physicians and nurses, are the primary source of education for all patients. More direct provider involvement is needed. Initiation of education earlier in the course of disease may increase overall patient satisfaction. This survey finds support for focusing education on the benefits of transplantation and home therapies.

Disclosures

Dr. Walker, Mr. Abbott, and Ms. Sexton are employees of Baxter Healthcare Corporation. The other authors have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions. Part of this material was presented in abstract form at the annual meeting of the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs; May 27 through 29, 2010; Baltimore, MD.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1. Mehrotra R, Marsh D, Vonesh E, Peters V, Nissenson A: Patient education and access of ESRD patients to renal replacement therapies beyond in-center hemodialysis. Kidney Int 68: 378–390, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The USRDS Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Study: Wave 2. United States Renal Data System. Am J Kidney Dis 30: S67–S85, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Finkelstein FO, Story K, Firanek C, Barre P, Takano T, Soroka S, Mujais S, Rodd K, Mendelssohn: Perceived knowledge among patients cared for by nephrologists about chronic kidney disease and end-stage renal disease therapies. Kidney Int 74: 1178–1184, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC: The views of patients and careers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: Systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ 340: c112, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Curtis CE, Rothstein M, Hong BA: Stage-specific educational interventions for patients with end-stage renal disease: Psychological and psychiatric considerations. Prog Transplant 19: 18–24, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Collins AJ, Foley RN, Gilbertson DT, Chen SC: The state of chronic kidney disease, ESRD, and morbidity and mortality in the first year of dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: S5–S11, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levin A: Consequences of late referral on patient outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 15: 3: 8–13, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Golper T: Patient education: Can it maximize the success of therapy? Nephrol Dial Transplant 16: 20–24, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lacson E, Lazarus JM, Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA, Hakim RM: Balancing Fistula First with Catheters Last. Am J Kidney Dis 50: 379–395, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rehman R, Schmidt RJ, Moss AH: Ethical and legal obligation to avoid long-term tunneled catheter access. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 456–460, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sarrias Lorenz X, Bardon Otero E, Vila Paz ML: Patients in pre-dialysis: Decision taking and free choice of treatment. Nefrologia 28: 119–122, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mason J, Stone M, Khunti K, Farooqi A, Carr S: Educational needs for blood pressure control in chronic kidney disease. J Ren Care 33: 134–138, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pauly RP: Nocturnal home hemodialysis and short daily hemodialysis compared with kidney transplantation: Emerging data in a new era. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 16: 169–172, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Masterson R: The advantages and disadvantages of home hemodialysis. Hemodial Int 12: S16–S20, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Juergensen E, Wuerth D, Finkelstein SH, Juergensen PH, Bekui A, Finkelstein FO: Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis: Patient's assessment of their satisfaction with therapy and the impact of the therapy on their lives. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 1191–1196, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rubin HR, Fink NE, Plantinga LC, Sadler JH, Kliger AS, Powe NR: Patient ratings of dialysis care with peritoneal dialysis vs hemodialysis. JAMA 291: 697–703, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kutner NG, Zhang R, Barnhart H, Collins AJ: Health status and quality of life reported by incident patients after 1 year on haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 20: 2159–2167, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. U.S. Senate: The Medicare Improvements for Patients and Providers Act of 2008 (MIPPA), PL 110-275, 2008

- 19. Buettner K, Fadem SZ: The Internet as a tool for the renal community. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 15: 73–82, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schatell D, Wise M, Klicko K, Becker BN: In-center hemodialysis patients' use of the Internet in the United States: A national survey. Am J Kidney Dis 48: 285–291, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]