Abstract

Rhodium carboxylate complexes (1 mol %) catalyze the migration of electron withdrawing groups to selectively produce 3-substituted indoles from β-substituted styryl azides. The relative order of migratorial aptitude for this transformation is ester ≪ amide < H < sulfonyl < benzoyl ≪ nitro.

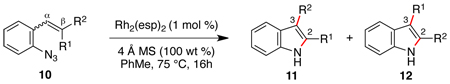

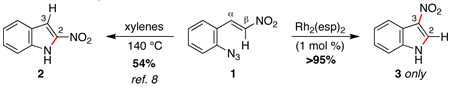

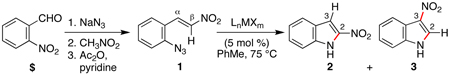

Reactions that involve a selective migration event can convert simple, readily accessible starting materials into complex functionalized products. While selective 1,2-shifts of alkyl-, aryl-, or other electron-releasing groups are well established in organic synthesis,1 the migration of strong electron-withdrawing groups are underdeveloped2 and have the potential to be powerful synthetic tools for constructing important biologically active small molecules.3–5 While nitro group migrations have been observed in isolated cases,6 these transformations have not been harnessed for the regioselective synthesis of nitro-substituted N-heterocycles. Styryl azides are established as useful indole precursors,7 and our group has previously reported that Rh2(II) octanoate catalyzes a phenyl group migration to transform β,β-diphenylstyryl azide into 2,3-diphenylindole.2b When the styryl azide contains a β-hydrogen, a C–H amination reaction occurs: thermolysis of β-nitro-substituted 1 was reported by Gribble and co-workers to produce 2-nitroindole 2 as the major product (eq 1).8 Herein, we report that Rh2(II) carboxylates promote a fundamental change in the reactivity of 1 to form 3-nitroindole as the exclusive product thereby providing a new synthetic method for N-heterocycle formation.

|

(1) |

A variety of transition metal complexes were examined to catalyze the formation of nitroindole from stryryl azide 1, which was synthesized in three steps from 2-nitrobenzaldehyde (Table 1).9 To our surprise, exposure of azide 1 to Rh2(II)-carboxylates (5 mol %) formed 3-nitroindole as the only product.10 Minimal optimization was required to identify the optimal conditions for this transformation: 1 mol % of Rh2(esp)2 11 in toluene cleanly converted 1 to 3 in >95% isolated yield with no observable 2-nitroindole byproduct. Other Rh2(II)-carboxylates were found to be nearly as efficient (cf. entries 3 and 4),12 except for Rh2OAc4, which was unreactive. In addition to these complexes, examination of a series of known N-atom transfer catalysts identified only RuCl3•hydrate13 to be competent, although less efficient than Rh2(esp)2 (entry 5). Other transition metal complexes, including CoTPP and [Ir(cod)OMe]2 (entries 6 and 7)14 afforded <10% of 2 and 3, whereas Cu- or Fe salts failed to react with the styryl azide.15,16

Table 1.

Optimization of Reaction Conditions.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | Catalyst | conv., %a | yield, %a | 2:3 |

| 1 | none | 0 | 0 | n.a. |

| 2 | Rh2(esp)2a | 99 | 95 | 0:100 |

| 3 | Rh2(O2CC7H15)4 | 95 | 89 | 0:100 |

| 4 | Rh2(O2CC3F7)4 | 97 | 90 | 1:99 |

| 5c | RuCl3•nOH2 | 89 | 67 | 1:99 |

| 6 | CoTPP | 17 | 7 | 43:57 |

| 7 | [Ir(cod)OMe]2 | 29 | trace | 100:0 |

As determined using 1H NMR spectroscopy.

esp = α,α,α',α'-tetramethyl-1,3-benzenedipropionate.

Reaction performed without the addition of MS in 1,2-dimethoxyethane.

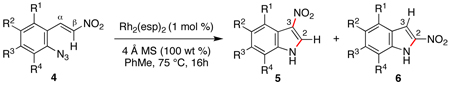

Using our optimized conditions, the scope of the rhodium(II)-catalyzed formation of nitroindoles from β-nitro-substituted styryl azides 4 was examined (Table 2). A series of 3-nitroindoles were produced selectively from substrates bearing a range of R1-, R2-, or R3 substituents (entries 1 – 9). The catalyst loading could be reduced when the reaction scale was increased: 2 mmol of styryl azide 4c required only 0.1 mol % of Rh2(esp)2 to be converted to indole 5c. Only when an R4-substituent was introduced to azide 4 did 2-nitroindole formation become a competitive process (entries 10 – 14). While a mixture of indoles 5 and 6 were obtained for aryl-, methyl- and methoxy R4-groups, exposure of azide 4n bearing a strong ortho-electron-withdrawing group (R4 = CF3) to reaction conditions afforded only 2-nitroindole 6n.

Table 2.

Scope of Rh(II)-Catalyzed NO2 Migratorial Reactions.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | 4 | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | yield, %a | 5:6b |

| 1 | a | H | H | OMe | H | 91 | >95:5 |

| 2 | b | H | H | Cl | H | 79 | >95:5 |

| 3c | c | H | H | CF3 | H | 96 | >95:5 |

| 4 | d | H | H | CO2Me | H | >95 | >95:5 |

| 5 | e | H | Br | H | H | 87 | >95:5 |

| 6 | f | H | Cl | H | H | 90 | >95:5 |

| 7 | g | H | CO2Me | H | H | >95 | >95:5 |

| 8 | h | H | OCH2O | H | 93 | >95:5 | |

| 9 | i | Cl | H | H | H | >95 | >95:5 |

| 10 | j | H | H | CH=CHCH=CH | 94 | 49:51 | |

| 11 | k | H | H | H | OMe | >95 | 26:74 |

| 12 | l | H | H | H | Me | 97 | 30:70 |

| 13 | m | Br | H | H | Br | 71 | 8:92 |

| 14 | n | H | H | H | CF3 | 99 | >5:95 |

Isolated yield after SiO2 chromatography.

As determined using 1H NMR spectroscopy.

2 mmol scale using 0.1 mol% Rh2(esp)2.

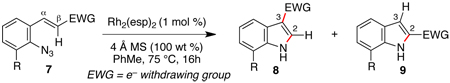

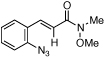

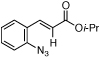

Styryl azides bearing electron-withdrawing groups at the β-position were investigated to determine if NO2-migration was a general phenomenon (Table 3). Aryl- and alkyl ketones migrated to provide only 3-substituted indoles (entries 1 – 3). In contrast, a mixture of indoles 8d and 9d was obtained from Weinreb amide 7d, and only the 2-carboxylate indole 9e was observed when isopropyl ester 7e was subjected to reaction conditions. These results show that migrations of amides and esters are less facile than ketones or nitro groups and suggest that stronger electron-withdrawing groups are more prone to migrate.17 Accordingly, sulfones were anticipated to migrate, and styryl azides 7f – 7h were converted to a 9:1 ratio in favor of 3-sulfonylindole 8 irrespective of the electronic environment of the sulfonyl group. In ortho-methoxy-substituted azide 7i, the migration of the sulfonyl group was inhibited affording only 2-sulfonylindole 9i. Together with 4j – 4n, these results suggest that migration can be suppressed with an additional ortho-substituent.

Table 3.

Scope of Migrating Group in Rh(II)-Catalyzed Migrations.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | 7 | Styryl azide | Major indole | yield, %a | 8:9 |

| 1 | a |  |

|

93 | >95:5 |

| 2 | b |  |

|

66 | >95:5 |

| 3 | c |  |

|

65 | >95:5 |

| 4 | d |  |

|

94 | 23:77 |

| 5 | e |  |

|

>95 | <5:95 |

| 6 | f |  |

>95 | 89:11 | |

| 7 | g |  |

78b | 89:11 | |

| 8 | h |  |

>95 | 90:10 | |

| 9 | i |  |

|

>95 | <5:95 |

Isolated yield after SiO2 chromatography.

3 mol % Rh2(esp)2 used.

To further examine the propensity for a group to migrate, several β-substituted styryl azides were submitted to reaction conditions and their products were compared (Table 4). In our first report,7b no alkyl- or aryl group migration was observed for styryl azides with β-hydrogen substituents (entry 1). Our subsequent study revealed that aryl groups migrate in preference to alkyl groups (entry 2).12a Azides 10d – 10f were constructed for an intramolecular competition between migrating groups (entries 3 and 4). Exposure of 10d and 10e to reaction conditions revealed that no phenyl group migration occurred in the presence of either a β-sulfone or β-amide. The reaction of azide 10f provided only 12f, the product of nitro migration; no benzoyl group migration was observed.

Table 4.

Intramolecular Competition Experiments to Compare Migration Preference.

Our results enable the construction of a scale for the migration of different β-substituents (eq 2). Styryl azide 10c reveals that aryl group migration is preferred over an alkyl shift.12a Neither group, however, will migrate in the presence of a β-hydrogen.7b Consequently, we rank their migratorial aptitude behind hydrogen. While hydrogen migration is preferred over amide migration in 7d, azide 10e revealed that when the β-hydrogen is replaced with a phenyl group, only amide migration is seen. Therefore amides are placed ahead of aryl groups but behind hydrogen. The difference in reactivity between 7a–c (only 3-carbonylindole) and 7f–h (90:10 favoring 3-sulfonylindole) suggests that sulfones should be positioned in between hydrogen and ketones. Finally, because only nitro group migration was seen for 10f, we rank it ahead of ketones. The propensity for these electron-withdrawing groups to migrate, however, hinges on the absence of a second ortho-electron withdrawing substituent on the aryl azide.

| (2) |

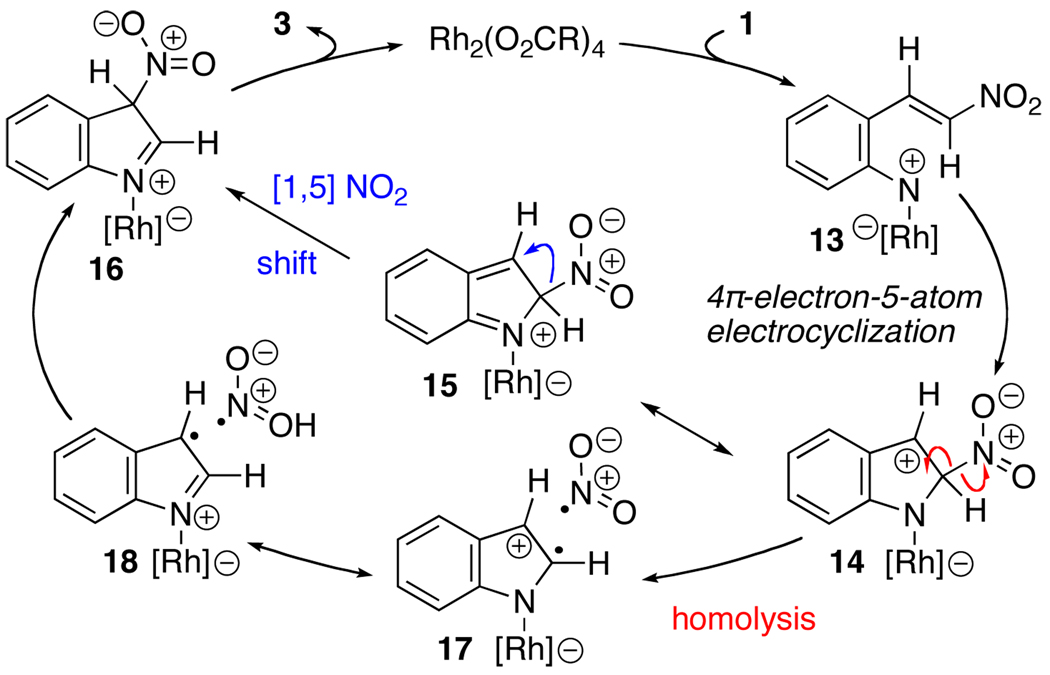

While a number of mechanisms could explain the reactivity patterns we observed, we propose that migration occurs from a common catalytic intermediate 14 (Scheme 1). Coordination of the Rh2(II)-carboxylate to the α- or γ-nitrogen atom followed loss of N2 forms rhodium nitrene 13.18,19 A 4π-electron-5-atom electrocyclization establishes the C–N bond and generates a carbocation on C3 in 14.20 From this intermediate, several different pathways could produce the desired migration. Examination of 15, a resonance structure of 14, reveals that a [1,5] sigmatropic shift could occur to form the C3–N bond in 16.2a,b Alternatively, the shift could occur stepwise. Homolysis of the C–O bond in 14 forms diradical 17. The mesomer 18 places the radical at C3 which could recombine to form the C–N bond in 16. A similar diradical mechanism was proposed for the rearrangement of sulfinate ions21 and nitro groups in electrophilic aromatic substitution.22 Tautomerization of 16 would form the 3-substituted indole.

Scheme 1.

Potential Mechanism for NO2 Migration.

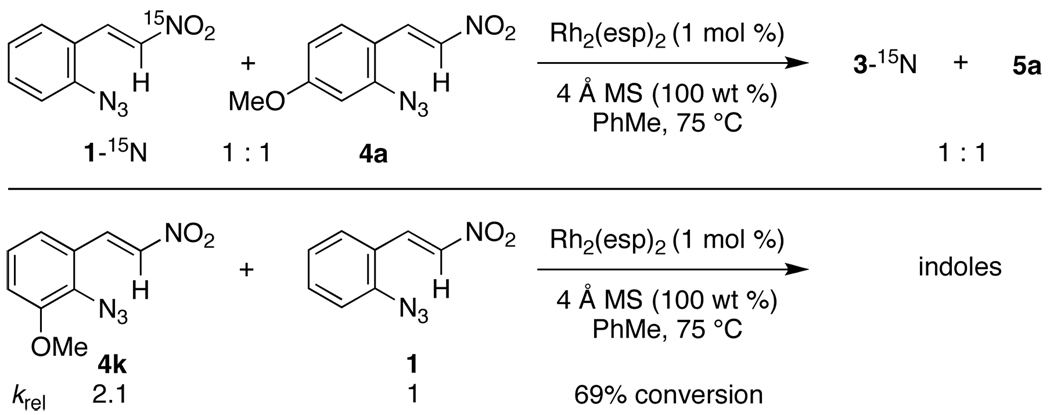

Several experiments were performed to test our mechanistic hypothesis (Scheme 2). A double crossover experiment between styryl azides 1-15N and 4a produced only indoles 3-15N and 5a to reveal that no solvent-separated reactive intermediates were formed in the catalytic cycle. As predicted by our previous mechanistic study,21 styryl azide 4k reacted 2.1 times faster than 1. This result confirms that the reaction can be accelerated when an electron-donating group is positioned to assist in N2 loss—supporting that C–N bond formation occurs via an electrocyclization.

Scheme 2.

Double Crossover- and Relative Rate Experiments.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that rhodium(II) carboxylate complexes catalyze the migration of electron-withdrawing groups to enable the selective formation of 3-substituted indoles from β-substituted styryl azides. Our data allowed for the construction of a scale, which categorizes the aptitude of migration for a range of functional groups. Future experiments will be centered on clarifying the mechanism of this reaction as well as exploiting these reactivity trends to produce complex, functionalized N-heterocycles from simple, readily accessible styryl azides.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to the National Institutes of Health NIGMS (R01GM084945) and the University of Illinois at Chicago for their generous financial support. We thank Mr. Furong Sun (UIUC) for high resolution mass spectrometry data.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, spectroscopic and analytical data (PDF) are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For reviews, see: Sromek AW, Gevorgyan V. Top. Curr. Chem. 2007;274:77. Snape TJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1823. doi: 10.1039/b709634h. Lang S, Murphy JA. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006;35:146. doi: 10.1039/b505080d. ten Brink G-J, Arends IWCE, Sheldonz RA. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:4105. doi: 10.1021/cr030011l. Overman LE, Pennington LD. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:7143. doi: 10.1021/jo034982c.

- 2.cf. (a) sulfur groups: Gairns RS, Moody CJ, Rees CW. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1985:1818. (b) acyl groups: Field DJ, Jones DW. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1980;1:1909. (c) nitro groups: Coombes RG, Russell LW. J. Chem. Soc. B. 1971:2443.

- 3.For examples of 3-nitro-substituted indoles, see: Tang J, Wang H. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2008;31:497. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.01.007. Al-Zereini W, Schuhmann I, Laatsch H, Helmke E, Anke H. J. Antibiot. 2007;60:301. doi: 10.1038/ja.2007.38.

- 4.For recent examples of 3-sulfonyl-substituted indoles, see: Bernotas RC, et al. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:1657. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.073. Samuele A, Kataropoulou A, Viola M, Zanoli S, La R, Giuseppe, Piscitelli F, Silvestri R, Maga G. Antiviral Res. 2009;81:47. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.09.008.

- 5.For examples of 3-acyl-substituted indoles, see: Kumar R, Balasenthil S, Manavathi B, Rayala SK, Pakala SB. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6649. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0909. Ramírez BG, Blázquez C, del Pulgar TG, Guzmán M, de Ceballos ML. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:1904. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4540-04.2005.

- 6.(a) Bakke JM. Pure Appl. Chem. 2003;75:1403. [Google Scholar]; (b) Myhre PC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:7921. [Google Scholar]; (c) Olah GA, Lin HC, Mo YK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:3667. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Driver TG. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:3831. doi: 10.1039/c005219c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shen M, Leslie BE, Driver TG. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:5056. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Sundberg RJ, Russell H, Ligon W, Jr, Lin L-S. J. Org. Chem. 1972;37:719. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelkey ET, Gribble GW. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997;38:5603. [Google Scholar]

- 9.For the reaction conditions surveyed, refer to the Supporting Information.

- 10.2- And 3-nitroindoles can generally be distinguished by the position of the C2 proton (~8.5 ppm) and C3 proton (~7.5 ppm) in DMSO-d6.

- 11.(a) Zalatan DN, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7558. doi: 10.1021/ja902893u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fiori KW, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:562. doi: 10.1021/ja0650450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Espino CG, Fiori KW, Kim M, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:15378. doi: 10.1021/ja0446294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.For leading reports of Rh(II)-nitrene chemistry, see: Sun K, Liu S, Bec P, Driver TG. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;50:1702. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006917. Stoll AH, Blakey SB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2108. doi: 10.1021/ja908538t. Zalatan DN, Du Bois J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9220. doi: 10.1021/ja8031955. Liang C, Collet F, Robert-Peillard F, Müller P, Dodd RH, Dauban P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:343. doi: 10.1021/ja076519d. Huard K, Lebel H. Chem.–Eur. J. 2008;14:6222. doi: 10.1002/chem.200702027. Stokes BJ, Dong H, Leslie BE, Pumphrey AL, Driver TG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7500. doi: 10.1021/ja072219k. Lebel H, Huard K, Lectard S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14198. doi: 10.1021/ja0552850.

- 13.Shou WG, Li J, Guo T, Lin Z, Jia G. Organometallics. 2009;28:6847. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Ruppel JV, Kamble RM, Zhang XP. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4889. doi: 10.1021/ol702265h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gao G-Y, Jones JE, Vyas R, Harden JD, Zhang XP. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:6655. doi: 10.1021/jo0609226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ragaini F, Penoni A, Gallo E, Tollari S, Gotti CL, Lapadula M, Mangioni E, Cenini S. Chem.–Eur. J. 2003;9:249. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cu: Chiba S, Zhang L, Lee J-Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:7266. doi: 10.1021/ja1027327. Chiba S, Wang YF, Lapointe G, Narasaka K. Org. Lett. 2008;10:313. doi: 10.1021/ol702727j.

- 16.Fe: Shen M, Driver TG. Org. Lett. 2008;10:3367. doi: 10.1021/ol801227f. Bacci JP, Greenman KL, Van Vranken DL. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:4955. doi: 10.1021/jo0340410. Bach T, Schlummer B, Harms K. Chem.—Eur. J. 2001;7:2581. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010618)7:12<2581::aid-chem25810>3.0.co;2-o.

- 17.As compared using σpara-values, see: Hansch C, Leo A, Taft RW. Chem. Rev. 1991;91:165.

- 18.For leading crystal structures of metal azide complexes, see: Waterman R, Hillhouse GL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12628. doi: 10.1021/ja805530z. Fickes MG, Davis WM, Cummins CC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:6384.

- 19.For a computational study on the mechanism of copper nitrenoid formation from azides, see: Badiei YM, Dinescu A, Dai X, Palomino RM, Heinemann FW, Cundari TR, Warren TH. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:9961. doi: 10.1002/anie.200804304.

- 20.Stokes BJ, Richert KJ, Driver TG. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:6442. doi: 10.1021/jo901224k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Baidya M, Kobayashi S, Mayr H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4796. doi: 10.1021/ja9102056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hudson RF, Record KAF. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1978;2:822. [Google Scholar]

- 22.cf. Esteves PM, de M, Carneiro JW, Cardoso SP, Barbosa AGH, Laali KK, Rasul G, Prakash GKS, Olah GA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4836. doi: 10.1021/ja021307w. Kochi JK. Acc. Chem. Res. 1992;25:39. Perrin CL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:5516.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.