Abstract

Hierarchical linear models were used to examine trajectories of impulsivity and capability between ages 10 and 25 in relation to suicide attempt in 770 youths followed longitudinally: intercepts were set at age 17. The impulsivity measure assessed features of urgency (e.g., poor control, quick provocation, and disregard for external constraints); the capability measure assessed aspects of self-esteem and mastery. Compared to nonattempters, attempters reported significantly higher impulsivity levels with less age-related decline, and significantly lower capability levels with less age-related increase. Independent of other risks, suicide attempt was related significantly to higher impulsivity between ages 10 and 25, especially during the younger years, and lower capability. Implications of those findings for further suicidal behavior and preventive/intervention efforts are discussed.

Certain personality traits or cognitive styles are hypothesized to increase risk for suicide. In particular, individual qualities that reflect a lack of impulse control (e.g., a disregard for social constraints, acting rashly and without forethought, excitement-seeking, or easily provoked or prone to anger) have been linked to elevated rates of suicide and suicide attempt (e.g., Beautrais, Joyce, & Mulder, 1999; Brent et al., 1994; Brent et al., 2002; Brodsky, Malone, Ellis, Dulit, & Mann, 1997; Cuomo, Sarchiapone, Giannantonio, Mancini, & Roy, 2008; Diaconu & Turecki, 2009; Frances & Blumenthal, 1992; Greening et al., 2008; Hyde, Kirkland, Bimler, & Pechtel, 2005; Maloney, Degenhardt, Darke, & Nelson, 2009; Melhem et al., 2007; Rotheram-Borus, Trautman, Dopkins, & Shrout, 1990; Swann, Lijffijt, Lane, Steinberg, & Moeller, 2009; Wu et al., 2009; Yang & Clum, 2000). That body of research is based predominantly on psychiatric or incarcerated samples, however, whereas comparable work based on population-based samples is limited. Moreover, findings typically are based on a single assessment of impulsivity, and do not take into account the potential for age-related change in personality traits (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000). In fact, longitudinal change in impulsivity has been implicated in subsequent change in impulsivity-related disorders known to increase risk for suicidality (Warner et al., 2004), suggesting that this probable risk pathway to suicide behavior may be interrupted. Nonetheless, to date, developmental change in the relation between impulsivity and suicidality has been inferred from evidence based primarily on psychological autopsy that differences in impulsivity levels are related to the age at which suicide completers died (McGirr et al., 2008).

As impulsivity is a multifaceted construct (Evenden, 1999), it is not surprising that studies differ substantially as to how it is defined and assessed. Existing measures constitute a not insignificant assortment of (sometimes overlapping) scales of related but distinct personality facets labeled excitability, cognitive impulsivity, novelty-seeking, sensation-seeking, lack of constraint, adventurousness, and susceptibility to boredom (Depue & Collins, 1999), to name a few. To increase understanding of this heterogeneous construct, Whiteside and Lynam (2001) utilized exploratory factor analysis to identify four separate personality facets associated with impulsive behaviors from among several commonly used measures of impulsivity, including, the Temperament and Character Inventory (Cloninger, Przybeck, & Svrakic, 1991); the Personality Research Form Personality Scale (Jackson, 1984); the I-7 Impulsiveness Questionnaire (Eysenck, Pearson, Easting, & Allsopp, 1985); the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-II (Patton, Stanford, & Barratt, 1995); and the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R; Costa & McCrae, 1992), which used the Five Factor Model (FFM) of personality as a framework (McCrae & Costa, 1990). The first personality facet in Whiteside and Lynam’s model, labeled Urgency, corresponds to the NEO-PI-R impulsivity facet (FFM Neuroticism domain) and centers on poor impulse control, often in the circumstance of negative affect. The second facet, labeled Premeditation, corresponds to the NEO-PI-R deliberation facet (FFM Conscientiousness domain) and focuses on the (lack of) ability to evaluate an action’s consequences before acting, the most common conceptualization of impulsivity. The third facet, labeled Perseverance, corresponds to the NEO-PI-R self-discipline facet (FFM Conscientiousness domain) and reflects the (lack of) ability to follow through on tasks that may be tedious or difficult. The fourth facet, Sensation-Seeking, corresponds to the NEO-PI-R excitement-seeking facet (FFM Extraversion domain) and entails engaging in risk-taking for the sake of excitement or new experiences.

Our measure of impulsivity, albeit unique to our study, is comprised of items adapted from established measures utilized by Whiteside and Lynam (2001) (or from earlier versions). Although not in perfect alignment, scale items best reflect the poor behavioral control, lack of regard for external (social) constraints, quick provocation, and maladaptive or inappropriate response as described by the Urgency factor. This form of impulsivity was shown to have the most robust association with psychopathology compared to forms of impulsivity that center on (not) assessing potential repercussions prior to acting (Premeditation), persisting (vs. giving up) on dull or hard tasks (Perseverance), or seeking out novel or dangerous activities (Sensation-Seeking), also implicated in impulse-related disorders (e.g., borderline personality disorder, substance abuse disorders) (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001, 2003; Whiteside, Lynam, Miller, & Reynolds, 2005). Empirical correspondence with features of neuroticism may make this form of impulsivity a key risk for suicide attempt. Nonetheless, Yen et al. (2009) found that premeditation was the sole type of impulsivity from among those forms to be related to suicide attempt independent of negative affectivity as well as additional putative risks, indicating that more than one form of impulsivity may be implicated in increased vulnerability to suicidal behaviors.

Others have focused on individual characteristics that may act as a deterrent to suicidality. In particular, a high level of self-esteem has been associated with lowered risk for suicide and suicide attempt among young persons (Beautrais et al., 1999; McGee, Williams, & Nada-Raja, 2001). Measures of self-esteem assess the degree of self-worth or self-valuation held by the individual, characteristics that at elevated levels are intrinsically incompatible with taking one’s own life. Additionally, measured indicators of beliefs held by young persons regarding their ability to exert control over their environment (i.e., locus of control) or to cope effectively in the face of adversity (i.e., mastery) also have been linked to decreased risk for suicide-related behaviors (Beautrais et al., 1999; Evans, Owens, & Marsh, 2006; Lauer, de Man, Marques, & Ades, 2008). Such self-attributes develop over time and are based in part on cognitive and emotional growth; nonetheless, maturational deficits often found in at-risk youths may interfere with the development of these more positive facets of personality.

Therefore, in addition to impulsivity, we also examine key positive attributes reported to decrease risk for suicide attempt and other suicide behavior in young people. Items from shortened versions of the Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) and the Mastery Scale (Pearlin and Schooler, 1978) were aggregated to form the Capability Scale, which centers on these beliefs. Owing to the salient role played by past experiences in shaping cognitive perceptions (Pearlin, Nguyen, Schieman, & Milkie, 2007; Sameroff, Seifer, & Bartko, 1997), such beliefs may change over time as a function of history of accomplishments and failures; yet even less is known regarding the impact of time-varying perceptions of capability on suicidal risk.

Increased understanding of patterns of development and change in facets of personality implicated in suicide susceptibility would inform intervention/preventive efforts targeting at-risk individuals in both community and clinical settings. In the current study, we investigated features of impulsivity and capability as related to suicide attempt with longitudinal data drawn from a large community sample of individuals followed in multiple waves from childhood into adulthood. First, change in impulsivity and capability from age 10 to age 25 was examined using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM): two separate trajectories were examined for each of these personality facets, one for individuals reported (by self or mothers) to have attempted suicide and one for all other individuals. Two basic questions were asked: (1) What is the average level of impulsivity and the average level of capability at age 17, the midpoint of the assessed age period and approximate age at which onset of suicide attempt peaks (Kessler, Borges, & Walters, 1999)? (2) What is the shape of the change function: linear (equal rates of change over age) or curvilinear (a pattern of accelerated or decelerated change)? Additionally, we examined the relationships between those trajectories and the trajectory of suicide attempt between ages 10 and 25 independent of other suicide-related risks.

METHOD

Sample

Data are based on the Children in the Community study, an ongoing longitudinal investigation of early risk for and long-term consequences of childhood psychopathology. First interviewed in 1983 (T1), a cohort of 776 youths (51% female; 91% European Caucasian, 8% African American Black) whose families were randomly selected from rural, suburban, and urban areas in two upstate New York counties for study participation were followed into adulthood. Comparisons with 1980 Census data indicated high demographic comparability to families with same-aged children living in the north-eastern United States (Cohen & Cohen, 1996). Reinterviews of mothers and youths took place nearly 3 years later (T2), with 776 families participating, and 10 years later (T3), with 717 families participating, resulting in a 92.4% retention rate over that period. There were no significant differences between those not interviewed at T3 and those interviewed at T3 on study variables assessed in prior waves (sex, history of abuse, suicide attempt, impulsivity, and capability). The current study is based on data from those three waves conducted at cohort mean ages 13.7 (SD = 2.6) (T1), 16.1 (SD = 2.8) (T2), and 22.0 (SD = 2.7) (T3). The current study sample is composed of 770 youths (six youths who had missing data pertaining to main study variables at more than one assessment point were eliminated from the analyses), of whom 715 were interviewed in all three waves and 55 were interviewed in two waves.

Procedure

Mothers and youths were interviewed at home simultaneously but separately by pairs of trained lay interviewers on a wide range of individual and social factors central to child development and behavior. Study procedures followed appropriate institutional guidelines and were approved by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the New York State Psychiatric Institute IRB. Written informed consent or assent was obtained from all participants after interview procedures were fully explained. Data are protected by a National Institutes of Health Certificate of Confidentiality.

Measures

Impulsivity was assessed at mean ages 13.7, 16.1, and 22.0, with seven self-administered questionnaire items. Five items had an item internal consistency (IIC: correlation between the specific item and the hypothesized scale, corrected for overlap) score ≥0.4 across the three assessments and two items had an IIC score ≥0.4 across two assessments; specific items and IIC scores are shown in Table 1. Exploratory factor analysis was performed on these seven impulsivity items using principal component factoring, which yielded a single eigenvalue >1.0 across the three assessments: values equivalent to 2.85, 2.70, and 2.80 explained 41.0% of the scale variance at T1, 37.9% at T2, and 40.1% at T3, respectively. Resulting scales had adequate internal consistencies (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73, 0.72, and 0.75). Each item on the impulsivity scale was rated on a 4-point Likert scale (see Table 1 for response options); items were scored so that higher scores indicated greater self-reported impulsivity. Raw mean (SD) scaled scores were 15.7 (4.5), 15.3 (3.9), and 14.7 (3.8) at successive assessments.

TABLE 1.

Item Internal Consistency (IIC) of the Seven-Item Impulsivity Scale and the Seven-Item Capability Scale

| Individual items | T1 | T2 | T3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Impulsivity scale | |||

| I often act without stopping to think (scoring reversed)a | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.41 |

| I often lose my temper at people (scoring reversed)a | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.55 |

| I often feel like swearing (scoring reversed)a | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.48 |

| I often blurt out things without thinking (scoring reversed)a | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.41 |

| When rules get in my way I ignore them (scoring reversed)a | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.45 |

| I am often called hot-headed or bad-tempered (scoring reversed)a | 0.48 | 0.44 | 0.47 |

| I get into trouble at school or work (scoring reversed)a | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| Capability scale | |||

| There is no way I can solve my problemsb | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.51 |

| I often feel helpless dealing with problemsb | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.53 |

| I can do whatever I set my mind to (scoring reversed)b | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.40 |

| I don’t have much to be proud ofa | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

| I feel that my life is very useful (scoring reversed)a | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.55 |

| I am a useful person to have around (scoring reversed)a | 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.44 |

| I have a number of good qualities (scoring reversed)a | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.48 |

Response options: 1 = definitely true about me; 2 = mostly true but not completely true about me; 3 = mostly false but not completely false about me; 4 = definitely false about me.

Response options: 1 = strongly agree; 2 = agree; 3 = disagree; 4 = strongly disagree.

The construct capability also was assessed at mean ages 13.7, 16.1, and 22.0 with seven self-administered questionnaire items on individual characteristics related to perceived mastery or coping (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978) and self-proclaimed worth (Rosenberg, 1965). Six items had an IIC score ≥0.4 across the three assessments and one item had an IIC score ≥0.4 across two assessments; specific items and IIC scores are shown in Table 1. Exploratory factor analysis was performed on the seven capability items using principal component factoring, which yielded one single eigenvalue >1.0: values equivalent to 2.80, 2.77, and 2.89 explained 40.2%of the scale variance at T1, 39.4% at T2, and 41.3% at T3, respectively. Resulting scales had adequate internal consistencies comparable to the impulsivity scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74, 0.72, and 0.76). Items on the capability scale were rated on one of two 4-point Likert scales (see Table 1 for response options); items were scored so that higher scores indicated greater self-reported capability. Raw mean (SD) scaled scores were 22.0 (2.9), 22.2 (3.0), and 22.2 (3.0) at successive assessments.

Mothers were assessed for lifetime major depressive disorder (MDD) at T3 by trained experienced interviewers using a structured interview covering DSM–IIIR criteria and suicide attempts. Of the 657 mothers assessed, 102 (15.5%) reported lifetime MDD or attempted suicide (hereafter referred to as maternal risk). As recommended by Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken (2003), to maintain as large a sample as possible a missing flag variable was used to control for the potential effects of the 113 youths with missing data on maternal risk.

A measure of physical or sexual abuse of the youth before age 18 was derived from official reports or youth reports after age 18. Of the 677 individuals with information, 60 (8.9%) had a history of physical or sexual abuse before age 18. A missing flag variable was used to control for the potential effects of the 93 youths with missing data on history of abuse.

Youths and mothers responded to parallel interview items about suicide attempts by the youth, with attempt defined as confirmation by either informant that the youth had tried to kill him or herself. The actual question asked at T1, T2, and T3 was “Did you (your child) ever try to kill yourself (him/herself)?”; 68 (8.8%) youths were reported to have made a suicide attempt. Information on age at which attempt(s) occurred also was obtained.

Developmental Trajectories of Impulsivity and Capability

Hierarchical linear models using SAS PROC MIXED (SAS Institute, Inc., 2002) were used to estimate individual (level 1) trajectories and average (level 2) trajectories of impulsivity and capability between ages 10 and 25, including estimated values at age 17 (the average trajectory midpoint) and annual and potential curvilinear changes over the assessed period. To obtain those estimates, repeated measures of impulsivity and capability were employed as dependent variables in individual growth models (Chen & Cohen, 2006); residual diagnostics were used to assess the adequacy of the fitted models. Histograms of residuals did not indicate discernable skew, and normal quantile plots displayed no systematic departure from a straight line. Accordingly, the normal residual assumption is tenable in our data.

Basic models for trajectories of impulsivity and capability (Model 1) examined fixed average linear and quadratic age changes and were the basis for cumulative models examining associations between each trajectory and sex of youth, maternal risk, youth history of physical or sexual abuse (Model 2); and suicide attempt (Model 3). Suicide attempt, which was assessed concurrently with impulsivity and capability at T1, T2, and T3, also was treated as a time-varying variable. These analyses estimate both linear and nonlinear change in risk-related factors that may vary with age or over time; permit inclusion of persons not assessed at all time-points; tolerate unequal intervals between data points; and combine data from individuals assessed at different ages, allowing for fuller exploitation of longitudinal data relative to traditional regression. HLM has been used successfully in epidemiological (Cohen et al., 2005; Perrin, Chen, Sandberg, Malaspina, & Brown, 2007) and clinical (McArdle, Small, Bäckman, & Fratiglioni, 2005) studies when risk or protective factors measured repeatedly over time are hypothesized to influence concurrent or subsequent pathological features, thus capitalizing on multiple assessments of predictors.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Bivariate analyses using logistic regression conducted with SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., 2006) showed that the odds of making a suicide attempt over the assessed period increased significantly with maternal risk (OR = 2.91, 95% CI = 1.61–5.26) and history of abuse (OR = 5.00, 95% CI = 2.58–9.68), but did not change significantly with sex (OR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.49–1.35).

Developmental Trajectory Analyses by Suicidality Status

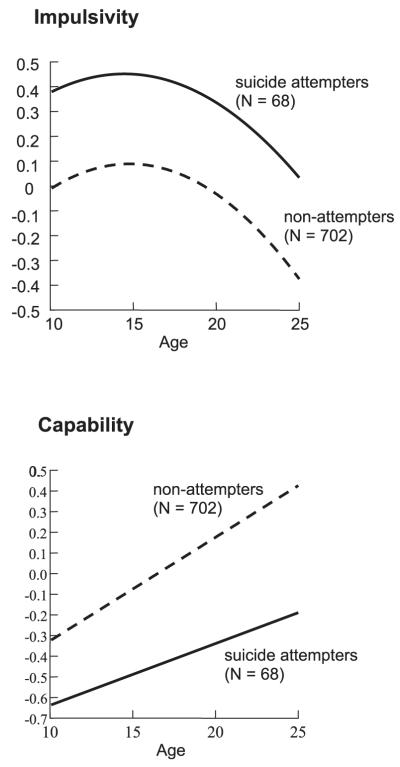

To facilitate interpretation of magnitudes of effect sizes, developmental trajectories of impulsivity and capability were standardized. The standardized estimates (β) of fixed age effects on impulsivity and capability at age 17, and the annual linear and (if observed) quadratic changes for the 68 youths with a lifetime suicide attempt and nonattempters are shown in Table 2. Because there was no quadratic change in either group for capability those estimates were not included in the table.

TABLE 2.

Developmental Trajectories of Impulsivity and Capability Between Ages 10 and 25 as Related to Trajectory of Suicide Attempt During that Period

| Impulsivity |

Capability |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p value | β (SE) | p value | |

| Suicide attempt (n = 68) | ||||

| Level at age 17 | 0.409 (0.117) | <.001 | −0.475 (0.103) | <.0001 |

| Annual linear change | −0.028 (0.018) | =.115 | 0.033 (0.190) | =.082 |

| Quadratic age change | a | a | ||

| No suicide attempt (n = 702) | ||||

| Level at age 17 | 0.067 (0.032) | =.037 | 0.028 (0.027) | =.307 |

| Annual linear change | −0.020 (0.005) | <.0001 | 0.050 (0.004) | <.0001 |

| Quadratic age change | −0.004 (0.001) | <.0001 | a | |

No significant quadratic age effect was observed.

At age 17, level of impulsivity was about six times higher in suicide attempters compared to nonattempters (0.409 SD vs. 0.067 SD). Moreover, in nonattempters there was a significant annual decline in impulsivity of 0.02 SD that tapered off with age (quadratic effect), whereas decline in attempters over that same age period did not reach conventional levels of significance (Figure 1, top panel). At age 17, level of capability was 0.028 SD in nonattempters and rose significantly by 0.05 SD per year; thus, by age 22 capability increased to 0.278 SD (0.028 SD + [0.05 SD × 5 years]). In contrast, among suicide attempters, at age 17 capability was −0.475 SD, ½ SD lower than sameaged nonattempters, and increased at a comparatively slower and nonsignificant rate (0.033 SD per year); thus, by age 22, capability remained below mean level among attempters at −0.31 SD (−0.475 SD + [0.033 SD × 5 years]). Figure 1 (bottom panel) shows the widening disparity in capability with age between suicide attempters and nonattempters owing to the more rapid and significant increase among nonattempters.

Figure 1.

Impulsivity and capability trajectories from age 10 to age 25 by suicide attempt over that same period in a population-based cohort of 770 individuals.

Multivariate Analyses

Standardized estimates (β) of associations between impulsivity and suicide attempt (controlling for sex of youth) are shown in Table 3. Average level of impulsivity at age 17 was significantly higher than the overall mean level between ages 10 and 25 (overall mean level = 0 given standardization of the scale) (β = 0.096, SE = 0.031, p < .01), but showed a significant annual decline (β = −0.020, SE = 0.005, p < .001) that slowed with increasing age (β = −0.004, SE = 0.001, p < .001) (Model 1). Considered simultaneously, maternal risk (β = 0.284, SE = 0.085, p < .001) and youth history of physical or sexual abuse (β = 0.151, SE = 0.075, p < .05) were independently related to a higher overall mean level of impulsivity between ages 10 and 25 (Model 2). The addition of fixed predictors maternal risk and youth history of physical or sexual abuse in Model 2 improved the fit to the data (χ2 = 38.8, df =2, p < .001). Independent of those risk effects, suicide attempt was significantly related to a higher overall mean level of impulsivity (β = 0.435, SE = 0.105, p < .001), a relation that was stronger during the younger years of the assessed age range (β = −0.075, SE = 0.025, p < .01) (Model 3). The addition of fixed predictors trajectory of suicide attempt and its interaction with age in Model 3 further improved the fit to the data relative to Model 2 (χ2 = 22.3, df = 2, p < .001). Additionally, although the relation between impulsivity and maternal risk remained significant in Model 3, the relation between impulsivity and youth history of physical or sexual abuse was reduced to a marginal one.

TABLE 3.

Developmental Changes in Impulsivity from Ages 10 to 25 in a Population-Based Cohort of 770 Individuals

| Covariates | Model 1 β (SE) |

Model 2a β (SE) |

Model 3a β (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random effects | |||

| Intercept (at age 17) | 0.451 (0.033)*** | 0.436 (0.032)*** | 0.430 (0.032)*** |

| Linear slope | 0.003 (0.001)** | 0.003 (0.001)** | 0.003 (0.001)** |

| Residual | 0.468 (0.024)*** | 0.472 (0.004)*** | 0.468 (0.024)*** |

| Fixed effects | |||

| Intercept (at age 17) | 0.096 (0.031)** | 0.059 (0.046) | 0.043 (0.045) |

| Annual linear age change | −0.020 (0.005)*** | −0.019 (0.005)*** | −0.018 (0.005)*** |

| Quadratic age change | −0.004 (0.001)*** | −0.005 (0.001)*** | −0.004 (0.001)*** |

| Maternal riskb | 0.284 (0.085)*** | 0.276 (0.084)*** | |

| Youth history of abusec | 0.151 (0.075)* | 0.143 (0.074) | |

| Suicide attempt | 0.435 (0.105)*** | ||

| Suicide attempt × Age | −0.075 (0.025)** | ||

| Goodness of fit | |||

| Parametrics | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| −2 log likelihood | 5911.5 | 5872.7 | 5850.4 |

| Chi-square | 38.8*** | 22.3*** | |

| Degrees of freedom | 2 | 2 |

Models controlled for sex.

Maternal history of major depression or suicide attempt.

Youth was physically or sexually abused before age 18.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Standardized estimates (β) of associations between capability and suicide attempt (controlling for sex of youth) are shown in Table 4. Average level of capability at age 17 did not differ significantly from the overall mean level between ages 10 and 25 (overall mean level = 0 given the standardization the scale) (β = −0.013, SE = 0.027), and showed a significant annual increase (β = 0.050, SE = 0.004, p < .001) (Model 1). Considered simultaneously, neither maternal risk (β = −0.018, SE = 0.082) nor youth history of physical or sexual abuse (β = 0.073, SE = 0.073) was related significantly to capability (Model 2); however, suicide attempt was significantly related to an overall lower mean level of capability between ages 10 and 25 (β = −0.533, SE = 0.106, p < .001) (Model 3). The addition of fixed predictor trajectory of suicide attempt improved the fit to the data relative to Model 2 (χ2 = 39.2; df = 2; p < .001).

TABLE 4.

Developmental Changes in Capability from Ages 10 to 25 in a Population-Based Cohort of 770 Individuals

| Covariates | Model 1 β (SE) |

Model 2a β (SE) |

Model 3a β (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random effects | |||

| Intercept (at age 17) | 0.380 (0.031)*** | 0.379 (0.031)*** | 0.364 (0.030)*** |

| Linear slope | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) |

| Residual | 0.558 (0.025)*** | 0.557 (0.027)*** | 0.554 (0.027)*** |

| Fixed effects | |||

| Intercept (at age 17) | −0.013 (0.027) | 0.029 (0.042) | −0.010 (0.042) |

| Annual linear age change | 0.050 (0.004)*** | −0.050 (0.004)*** | 0.051 (0.004)*** |

| Maternal riskb | −0.018 (0.082) | −0.001 (0.081) | |

| History of abusec | 0.073 (0.073) | −0.064 (0.072) | |

| Suicide attempt | −0.533 (0.106)*** | ||

| Goodness of fit | |||

| Parametrics | 5 | 7 | 9 |

| −2 log likelihood | 5994.9 | 5991.1 | 5951.9 |

| Chi-square | 3.8 (p > .05) | 39.2*** | |

| Degrees of freedom | 2 | 2 |

Models controlled for sex.

Maternal history of major depression or suicide attempt.

Youth was physically or sexually abused before age 18.

p < .001

DISCUSSION

This longitudinal study used multilevel modeling to examine developmental trajectories of impulsivity and capability between ages 10 and 25, and their associations with suicide attempt over that same period in a community sample of 770 youths. To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate whether age-related changes in these individual facets of personality contribute to the trajectory of suicide attempt over an interval spanning childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. Our findings support previous work that impulsive behaviors and beliefs about one’s capability are related to suicide attempt, but also extend them by providing estimates of the degree to which age-related change in impulsivity and capability among suicide attempters deviates from the norm.

We found that it is normative for impulsivity to decline from childhood to adulthood and then to taper off, which is in concert with findings based on youths with impulsivity-related pathological features in both epidemiological (Johnson et al., 2000; Winograd, Cohen, & Chen, 2008) and clinical (Biederman, Mick, & Faraone, 2000; Zanarini et al., 2007) samples. Thus, albeit it is not uncommon for young children to act rashly on impulse, break rules, and exhibit socially maladaptive behavior, it appears that this form of impulsivity becomes increasingly less frequent as they mature, probably owing in part to more effective emotional regulation and to increasing external pressure for restraint. However, our results showed that youths who attempted suicide deviated significantly from these normative patterns of development, exhibiting a higher level of this form of impulsivity at age 17 and a slower decline with age, suggesting a delay in those developmental tasks. Such poor impulse control may reflect biologically based individual differences in temperament that affect the capacity to actively control attentional and emotional responses (Cloninger, 1987; Putnam, Ellis, & Rothbart, 2001). Evidence that adult suicide attempters demonstrated executive and arousal inhibitory deficits that may lead to perseveration of deliberate thoughts and actions to end one’s life supports that theory (Legris & Van Reekum, 2006). The finding that youth suicide attempt and maternal MDD or suicide attempt were related independently to overall mean level of impulsivity between ages 10 and 25 (and to each other) supports others’ findings of a familial link among these factors (e.g., Brent et al., 2002; Melhem et al., 2007), but also indicates that their effects may be additive.

At the same time, we found that it is normative for youths to report enhanced capability as they advance through the adolescent years into adulthood, the kind of capability that comes with increasing recognition of one’s strengths, leading a progressively more useful and purposeful life, and becoming more adept at managing one’s life circumstances. Such enhanced capability likely reflects cognitive growth, cumulative accomplishments, and increasing success in dealing with challenging experiences. Individuals’ beliefs regarding the extent to which they are competent and able to effectively manage and adapt to significant change in their lives can be a critical resource for coping with adversity (Avison & Cairney, 2003). Here too, however, suicide attempters deviated significantly from normative patterns, showing a lower mean level of capability at age 17 and a slower increase with age: given the propensity for cognitive deficiencies and distortions reported among youthful suicide attempters, this finding suggests that positive personal attributes and accomplishments either go unrecognized or are perceived in a negative light by at-risk individuals. Perhaps the most notable outcome was the decreased risk for suicide attempt with a high overall mean level of capability between ages 10 and 25, a period over which suicide attempts grow increasingly more prevalent (Kessler et al., 1999).

These findings have implications regarding increased vulnerability for further suicidal behavior and for preventive/intervention efforts. The trajectory for impulsivity among nonattempters was to decline significantly and linearly with age; however, decline among suicide attempters was not significant, thus the risk presented by poor impulse control, quick provocation, and disregard of external constraints, features of impulsivity assessed in the current study, may continue to present a risk for future suicide attempt. Therefore, despite the focus on impulse control in younger children, it may be judicious to address such impulsivity in intervention/prevention efforts even during the late adolescent years to forestall later risk. By the same token, the low mean level of capability in middle to late adolescence (i.e., at age 17) and the slower nonsignificant increase in capability between ages 10 and 25 among suicide attempters relative to nonattempters also suggests that intervention/prevention efforts may do well to shore up that personality facet to increase its protective strength. Such negative beliefs are amenable to increased opportunities that would build a sense of growing capability. History of suicide attempt is a key predictor of subsequent suicide attempt; thus, contexts that facilitate such prospects also may deter future attempts.

The following limitations should be noted when interpreting these findings. Because the participants in our sample are of primarily European Caucasian background, generalizability of the results to other racial or ethnic groups is limited. However, this sample is representative of a large segment of the U.S. population (Cohen & Cohen, 1996); therefore, results may be generalized to a substantial proportion of community-dwelling individuals in the same age range. Although we considered a number of known factors that could influence associations between impulsivity or capability and suicide attempt (sex of youths, maternal MDD or suicide attempt, and youths’ histories of physical or sexual abuse), we did not address others (e.g., concurrent psychiatric disorders, parental history of abuse, disorders of the central nervous system [Mann, 2002]). Albeit measures of impulsivity and capability show adequate psychometric features with regard to their internal consistency and unidimensionality, they also are exclusive to our study; therefore, it is difficult to draw comparisons with others’ findings. The measure of suicide attempt used relied only on the one self- or mother-reported item “Did you (your child) ever try to kill yourself (him/herself)?” Failure to consider lethality (i.e., the medical consequences of the act) or seriousness of intent (full intent to die vs. ambivalence) may have resulted in an oversimplification of this study construct. We also did not address the issue of whether the association between impulsivity and suicide attempt is at least partly explained by concurrent impulse-related disorders. However, study analyses adjusted for powerful suicide-related risks with links not only to suicide attempt and impulsivity but to Axis I and Axis II psychopathology in these youths (e.g., Johnson, Cohen, Chen, Kasen, & Brook, 2006; Kasen et al., 2001). Moreover, others who have examined this issue in clinical samples report evidence that relations between excessive impulsivity and suicide behaviors are not a consequence of disorder (Dumais et al., 2005; Fenton, 2000; Kim et al., 2003; Sinclair, Mullee, King, & Baldwin, 2004). Finally, information on maternal MDD and suicide attempt and youth history of physical or sexual abuse was missing for substantial proportions of the sample (15.5% and 8.9%, respectively), requiring the use of missing flag variables in the analyses.

Nonetheless, this study also has notable strengths. Findings are based on longitudinal data drawn from a randomly selected population-based sample of youths and their mothers followed longitudinally in multiple waves. Additionally, the current study sample had a very high rate of retention, thus minimizing potential bias owing to participant attrition. Finally, this repeated measures design allowed us to examine developmental trajectories of individual facets of personality implicated in suicidality (impulsivity and capability) and trajectory of suicide attempt over that same period. This analytic strategy has several advantages, a key one being minimized variance due to local or time-limited influences with the estimation of each person’s trajectory mean at a fixed (constant) age and the average annual change (slope) prior and subsequent to that age.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant to Dr. Kasen by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (Project 1007504 [2009–2010]). The data analyzed come from the Children in the Community (CIC) study, Principal Investigator, Dr. Cohen. The CIC study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health through grants R01 MH36971 (1983–1985), R01 MH38916 (1985–1988), R01 MH49191 (1992–1995), and R01 MH60911 (2000–2010), with supplemental grant support from the National Institute for Justice through grant IJCX0029 (1999–2001). Dr. Kasen had full access to all study data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. The authors report no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Stephanie Kasen, Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Patricia Cohen, Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Henian Chen, Winthrop University Hospital, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, Stony Brook, NY, USA..

REFERENCES

- Avison WR, Cairney J, Schaie KW. Social structure, stress, and personal control. In: Zarit SH, Pearlin LI, editors. Personal control in social and life course contexts. Springer; New York: 2003. pp. 127–164. [Google Scholar]

- Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT. Personality traits and cognitive styles as risk factors for serious suicide attempts among young people. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 1999;29:37–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Mick E, Faraone SV. Age-dependent decline of symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Impact of remission definition and symptom type. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:816–818. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Johnson BA, Perper J, Connolly J, Bridge J, Bartle S, et al. Personality disorder, personality traits, impulsive violence, and completed suicide in adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:1080–1086. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199410000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Oquendo M, Birmaher B, Greenhill L, Kolko D, Stanley B, et al. Familial pathways to early-onset suicide attempt: Risk for suicidal behavior in offspring of mood-disordered suicide attempters. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:801–807. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky BS, Malone KM, Ellis SP, Dulit RA, Mann JJ. Characteristics of borderline personality disorder associated with suicidal behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1715–1719. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.12.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Cohen P. Utilizing individual growth model to analyze the change in quality of life from adolescence to adulthood. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2006;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:573–588. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180093014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1991;50:975–990. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Chen H, Kasen S, Johnson JG, Crawford T, Gordon K. Adolescent cluster A personality disorder symptoms, role assumption in the transition to adulthood, and resolution or persistence of symptoms. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:549–568. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J. Life values and adolescent mental health. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation: Analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PTJR, McCrae RR. Revised NEO personality inventory manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo C, Sarchiapone M, Giannantonio MD, Mancini M, Roy A. Aggression, impulsivity, personality traits, and childhood trauma of prisoners with substance abuse and addiction. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:339–345. doi: 10.1080/00952990802010884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 1999;22:491–569. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaconu G, Turecki G. Family history of suicidal behavior predicts impulsive-aggressive behavior levels in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;113:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumais A, Lesage AD, Lalovik A, Seguin M, Tonsignant N, Chawky N, et al. Is violent method of suicide a behavioral marker of lifetime aggression? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1375–1378. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WP, Owens P, Marsh SC. Environmental factors, locus of control, and adolescent suicide risk. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2006;22:301–319. [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:348–361. doi: 10.1007/pl00005481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Pearson PR, Easting G, Allsopp JF. Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness, and empathy in adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton WS. Depression, suicide, and suicide prevention in schizophrenia. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2000;30:34–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frances A, Blumenthal S. Personality as a predictor of youthful suicide. In: Davidson L, Linnoila M, editors. Risk factors for youth suicide. Hemisphere; New York: 1992. pp. 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- Greening L, Stoppelbein L, Fite P, Dhossche D, Erath S, Brown J, et al. Pathways to suicidal behavior in childhood. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38:35–44. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde T, Kirkland J, Bimler D, Pechtel P. An empirical taxonomy of social-psychological risk indicators in youth suicide. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;35:436–447. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DA. Personality research form manual. Research Psychologists Press; Goshen, NY: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Chen H, Kasen S, Brook JS. Parenting behaviors associated with risk for offspring personality disorder during adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63:579–587. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Skodol AE, Hamagami F, Brook JS. Age-related change in personality disorder trait levels between early adolescence and adulthood: A community-based longitudinal investigation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;102:265–275. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102004265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasen S, Cohen P, Skodol AE, Johnson JG, Smailes E, Brook JS. Childhood depression and adult personality disorders: Alternate pathways of continuity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:231–236. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:617–626. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Lesage A, Seguin M, Lipp O, Vanier C, Turecki G. Patterns of comorbidity in male suicide completers. Psychological Medicine. 2003;33:1299–1309. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer S, de Man AF, Marques S, Ades J. External locus of control, problem-focused coping, and attempted suicide. North American Journal of Psychology. 2008;10:625–632. [Google Scholar]

- Legris J, Van Reekum R. The neuropsychological correlates of borderline personality disorder and suicidal behaviour. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;51:131–142. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney E, Degenhardt L, Darke S, Nelson EC. Impulsivity and borderline personality as risk factors for suicide attempts among opioid-dependent individuals. Psychiatric Research. 2009;169:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ. A current perspective of suicide and attempted suicide. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2002;136:302–311. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-4-200202190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Small BJ, Bäckman L, Fratiglioni L. Longitudinal models of growth and survival applied to the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2005;18:234–241. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PTJR. Personality in adulthood. Guilford; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Williams S, Nada-Raja S. Low self-esteem and hopelessness in childhood and suicidal ideation in early adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2001;29:281–291. doi: 10.1023/a:1010353711369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGirr A, Renaud J, Bureau A, Seguín M, Lesage A, Turecki G. Impulsive-aggressive behaviours and completed suicide across the life cycle: A predisposition for younger age of suicide. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:407–417. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melhem NM, Brent DA, Ziegler M, Iyengar S, Kolko D, Oquendo M, et al. Familial pathways to early-onset suicidal behavior: Familial and individual antecedents of suicidal behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1364–1370. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Nguyen KB, Schieman S, Milkie MA. The life-course origins of mastery among older people. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:164–179. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L, Schooler C. The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1978;19:2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin MA, Chen H, Sandberg DE, Malaspina D, Brown AS. Growth trajectory during early life and risk of adult schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;191:512–520. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Ellis LK, Rothbart MK. The structure of temperament from infancy through adolescence. In: Eliasz A, Angleitner A, editors. Advances in research on temperament. Pabst Science; Lengerich, Germany: 2001. pp. 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, DelVecchio WF. The rank order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Borus MJ, Trautman PD, Dopkins SC, Shrout PE. Cognitive style and pleasant activities among female adolescent suicide attempters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:554–561. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.5.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ, Seifer R, Bartko WT. Environmental perspectives on adaptation during childhood and adolescence. In: Luthar SS, Burack JA, Cicchetti D, Weisz JR, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Perspectives on adjustment, risk, and disorder. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1997. pp. 507–526. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, Inc. SAS/STAT software: Version 9.0 (computer software) Author; Cary, NC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair JMA, Mullee MA, King EA, Baldwin DS. Suicide in schizophrenia: A retrospective case-control study of 51 suicides. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2004;30:803–811. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS, INC. SPSS 15.0 basic user’s guide. Prentice-Hall; Chicago, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Lijffijt M, Lane SD, Steinberg JL, Moeller FG. Severity of bipolar disorder is associated with impairment of response inhibition. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;116:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner MB, Morey LC, Finch JF, Gunderson JG, Skodol AE, Sanislow CA, et al. The longitudinal relationship of personality traits and disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:217–227. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. Understanding the role of impulsivity and externalizing psychopathology in alcohol abuse: Application of the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2003;11:210–217. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS Impulsive Behaviour Scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality. 2005;19:559–574. [Google Scholar]

- Winograd G, Cohen P, Chen H. Adolescent borderline symptoms in the community: Prognosis for functioning over 20 years. Journal of Child and Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:933–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C-S, Liao S-C, Lin K-M, Tseng MM-C, Wu EC-H, Liu S-K. Multidimensional assessments of impulsivity in subjects with history of suicidal attempts. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2009;50:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Clum GA. Childhood stress leads to later suicidality via its effect on cognitive functioning. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2000;30:183–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen S, Shea MT, Sanislow CA, Skodol AE, Grilo CM, Edelen MO, et al. Personality traits as prospective predictors of suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2009;120:222–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Silk KR, Hudson JI, Mcsweeney LB. The subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder: A 10-year follow-up study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:929–935. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]