Abstract

Purpose

Aberrant promoter hypermethylation of several known or putative tumor suppressor genes occurs frequently during the pathogenesis of various cancers including breast cancer. Many epigenetically inactivated genes involved in breast cancer development remain to be identified. Therefore, in this study we used a pharmacologic unmasking approach in breast cancer cell lines with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC) followed by microarray expression analysis to identify epigenetically inactivated genes in breast cancer.

Experimental Design

Breast cancer cell lines were treated with 5-aza-dC followed by microarray analysis to identify epigenetically inactivated genes in breast cancer. We then used bisulfite DNA sequencing, conventional methylation-specific PCR, and quantitative fluorogenic real-time methylation-specific PCR to confirm cancer-specific methylation in novel genes.

Results

Forty-nine genes were up-regulated in breast cancer cells lines after 5-aza-dC treatment, as determined by microarray analysis. Five genes (MAL, FKBP4, VGF, OGDHL, and KIF1A) showed cancer-specific methylation in breast tissues. Methylation of at least two was found at high frequency only in breast cancers (40 of 40) as compared with normal breast tissue (0 of 10; P < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test).

Conclusions

This study identified new cancer-specific methylated genes to help elucidate the biology of breast cancer and as candidate diagnostic markers for the disease.

Breast cancer is second to lung cancer as the leading cause of cancer death among women (1). According to the WHO, more than 1.2 million women worldwide will be diagnosed with breast cancer this year. The limitations of mammography have been documented (2, 3) especially for those women with premenopausal breast cancer. Suspicious lesions detected on mammography are analyzed by fine needle aspiration biopsy. However, the accuracy of cytomorphologic analysis relies mostly on the expertise of the pathologist, which has shown to have a false negative rate of 5% to 30% (4). The search for more sensitive and specific tests is ongoing. One approach is the identification of breast cancer–specific biomarkers and noninvasive methods for the detection of these biomarkers at an early stage (5-8).

Alterations in various genes that positively and negatively regulate cell function are involved in tumorigenesis (9). Many factors can affect gene function, including genetic alterations as well as epigenetic modifications. Epigenetic changes such as DNA methylation are some of the most common molecular alterations in human neoplasia (10-13). DNA hypermethylation refers to the addition of a methyl groupto the cytosine ring of those cytosines that precede a guanosine (referred to as CpG dinucleotides) to form methyl cytosine (5-methylcytosine). CpG dinucleotides are found at increased frequency in the promoter region of many genes. These CpGs are referred to as “CpG islands.” Methylation of these islands in the promoter region is frequently associated with reduced gene expression (12). Several tumor suppressor genes contain CpG islands in their promoters, and many of them show evidence of methylation silencing (14). Aberrant promoter methylation may affect genes involved in cell cycle control, DNA repair, cell adhesion, signal transduction, apoptosis, and cell differentiation (13-16). Epigenetic changes are an early event in carcinogenesis and are present in the precursor lesions of a variety of cancers including breast (17), lung (18), and colon (19). A summary list of hypermethylated genes in breast cancer can be found in ref. 20; many of these genes were found at low frequency (14) whereas others showed methylation in normal tissues as well (21).

Translational Relevance.

The novel methylation markers of breast cancer discovered in this study show great potential in molecular detection approaches. These markers can be detected in stage I breast cancers and therefore show promise in the early detection of breast cancer. The development of a blood-based test for breast cancer based on gene promoter methylation of these markers could augment current early detection approaches such as mammography. Moreover, methylated targets also have real therapeutic potential with the continuing development of demethylating agents that can be used in the clinic.

Although the number of hypermethylated genes in cancer is growing by testing candidate genes (i.e., methylation of known tumor suppressor genes in other cancer types), many epigenetically modified genes remain to be elucidated. Some authors suggest (22, 23) a range of 100 to 400 promoter hypermethylated CpG islands in a given tumor type, suggesting that other epigenetically inactivated genes involved in breast cancer development remain to be identified. We used pharmacologic unmasking of breast cancer cell lines with 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC) followed by expression microarray analysis to identify epigenetically inactivated genes in breast cancer. We then used bisulfite DNA sequencing, conventional methylation-specific PCR (MSP), and quantitative MSP to confirm breast cancer–specific methylation in novel genes. We found five promising cancer-specific methylated genes that shed light on the biology of breast cancer and may aid in diagnostic approaches.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

We used five different human breast cancer cell lines (BT-20, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, Hs578T, and MDA-MB-436). Cell lines were propagated in accordance with the instructions from American Type Culture Collection.

5-Aza-dC treatment of cells

Cell lines were treated with 5-aza-dC as previously described (24). Briefly, we seeded all cell lines (1 × 106) in their respective culture medium and maintained them for 24 h before treating them with 5 μmol/L 5-aza-dC (Sigma) for 3 d. We renewed medium containing 5-aza-dC every 24 h during the treatment. We handled control cells the same way, without adding 5-aza-dC. Stock solutions of 5-aza-dC were dissolved in PBS (pH 7.5). We prepared total RNA using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen).

Microarray

Affymetrix arrays were used for gene expression profiling per the manufacturer’s instruction. We used GeneChip Human Genome U133A Arrays containing >22,000 probe sets for analysis of >18,400 transcripts, which include ~14,500 well-characterized human genes. Biotinylated RNA probe preparation and hybridization were previously described (24).

Analysis of expression data

We computed gene expression summary values for Affymetrix GeneChipdata using the bioconductor package (which uses background adjustment, quantile normalization, and summarization; ref. 25).

Tissue samples and DNA extraction

We evaluated tissue samples from primary breast cancers (total 40 human samples). Tissue samples from 10 age-matched individuals without a history of malignancy were used as controls. The demographics of patient samples are listed in Table 1. Tissue samples were microdissected to isolate more than 70% epithelial cells in both neoplastic and nonneoplastic tissues. Cell pellets were digested with 1% SDS and 50 μg/mL proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim) at 48°C overnight, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation of DNA as previously described (26).

Table 1.

Demographics of patient samples

| Sample | Age (y) | LN met | Stage | ER | PR | Her-2 | Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 65 | N | I | 1 | 0 | ||

| 2 | 68 | N | I | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 38 | N | I | 1 | 1 | ||

| 4 | 46 | N | I | 1 | 1 | ||

| 5 | 69 | N | I | 1 | 1 | ||

| 6 | 50 | N | I | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC |

| 7 | 69 | N | I | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A |

| 8 | 45 | N | I | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC |

| 9 | 55 | N | IIA | 0 | 0 | + | Her-2 |

| 10 | 60 | N | IIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A |

| 11 | 42 | N | IIA | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC |

| 12 | 65 | N | IIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A |

| 13 | 43 | N | IIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A |

| 14 | 52 | N | IIA | 1 | 1 | ||

| 15 | 60 | N | IIA | 0 | 0 | ||

| 16 | 77 | N | IIA | 1 | 0 | ||

| 17 | 38 | N | IIA | 1 | 1 | ||

| 18 | 67 | N | IIA | 1 | 0 | ||

| 19 | 46 | N | IIA | 0 | 0 | ||

| 20 | 63 | N | IIA | 0 | 0 | ||

| 21 | 53 | Y | IIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A |

| 22 | 47 | Y | IIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A |

| 23 | 67 | Y | IIA | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC |

| 24 | 38 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | ||

| 25 | 53 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | ||

| 26 | 35 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | ||

| 27 | 53 | Y | IIB | 0 | 0 | ||

| 28 | 59 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | ||

| 29 | 50 | Y | IIB | 0 | 0 | ||

| 30 | 41 | Y | IIB | 1 | 0 | 0 | LUM A |

| 31 | 59 | Y | IIB | 0 | 0 | ||

| 41 | 62 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | LUM B | |

| 32 | 50 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | + | LUM A |

| 33 | 48 | Y | IIIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A |

| 34 | 35 | Y | IIIA | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC |

| 35 | 38 | Y | IIIA | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC |

| 36 | 50 | Y | IIIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A |

| 37 | 44 | Y | IIIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A |

| 38 | 80 | N | IIIB | 0 | 0 | ||

| 39 | 55 | Y | IIIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC |

| 40 | 53 | Y | IV | 0 | 0 |

NOTE: Breast cancer patients possessed tumors from stage I to stage IV, with and without lymph node metastasis. Estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, Her-2 status, as well as clinical subtype (luminal A, luminal B, and triple negative) are listed if available. Median age of cancer patients is 50 y. Normal breast tissue was obtained from disease-free women, median age 43 y. Abbreviations: LN met, lymph node metastasis; LUM A, luminal A; LUM B, luminal B; TNC, triple-negative cancer.

Bisulfite genomic sequence analysis, conventional MSP, and quantitative MSP

Bisulfite sequence analysis was done to determine the methylation status in cell lines and a limited number of tissues including primary tumors and age-matched normal controls from the same organ. We extracted genomic DNA as above and carried out bisulfite modification of genomic DNA as described previously (27). Bisulfite-treated DNA was amplified for the 5′ region that included at least a portion of the CpG island within 1 kb of the proposed transcriptional start site using primer sets (Supplementary Table S1). The primers for bisulfite sequencing were designed to hybridize to regions in the promoter without CpG dinucleotides. PCR products were gel-purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each amplified DNA sample was sequenced by the Applied Biosystems 3700 DNA analyzer using nested, forward, or reverse primers and BD terminator dye (Applied Biosystems). When necessary, MSP primers were designed to amplify methylated or unmethylated DNA.

For high-throughput analysis, we developed quantitative MSP for five genes. Briefly, bisulfite-modified DNA was used as template for fluorescence-based real-time PCR, as previously described (28). Amplification reactions were carried out in triplicate using 3 μL bisulfite-modified DNA. Primers and probes were designed to specifically amplify the promoters of the five genes of interest and the promoter of a reference gene, actin-B (ACTB). Primer and probe sequences and annealing temperatures are provided in Supplementary Table S2. Amplification reactions were carried out in 384-well plates in a 7900 Sequence Detector (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) and were analyzed by SDS 2.2.1 (Sequence Detector System; Applied Biosystems). Each plate included patient DNA samples, positive (in vitro methylated leukocyte DNA) and negative (normal leukocyte DNA or DNA from a known unmethylated cell line) controls, and multiple water blanks. Leukocyte DNA was methylated in vitro with excess SssI methyltransferase (New England Biolabs, Inc.) to generate completely methylated DNA. Serial dilutions (90-0.009 ng) of this DNA were used to construct a calibration curve for each plate. The relative level of methylated DNA for each gene in each sample was determined as a ratio of MSP for the amplified gene to ACTB and then multiplied by 1,000 for easier tabulation [(average value of triplicates of gene of interest / average value of triplicates of ACTB) × 1,000]. The samples were categorized as unmethylated or methylated based on detection of methylation above a threshold set for each gene. This threshold was determined by analyzing the levels and distribution of methylation, if any, in normal (nonneoplastic) age-matched tissues.

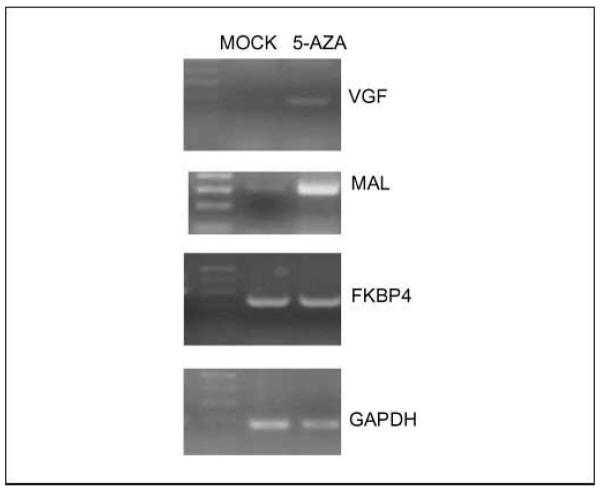

Reverse transcription-PCR

RNA was extracted from 5-aza-dC–treated as well as untreated breast cancer cell lines. Briefly, RNA was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen). Four micrograms of total RNA were reverse transcribed with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), then cDNA was amplified by PCR. Primer sequences and PCR conditions are available in Supplementary Table S3. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control. The PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Results

Validation of microarray data using cell lines

Microarray analysis in five human breast cancer cell lines (BT-20, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, Hs578T, and MDA-MB-436) identified 49 potential gene targets based on reactivation after treatment with 5-aza-dC. Of these 49 genes, two were not CpG rich, and seven were already known to harbor cancer-specific methylation after a literature search. Two genes were previously described by us (24) as methylated in breast cancer (KIF1A and OGDHL). The remaining 38 genes were validated in breast cancer cell lines (Table 2). Primers were designed for each gene and tested by bisulfite sequence analysis and/or MSP in one or more cell line that exhibited reexpression after demethylation treatment. Promoter methylation of 9 genes (9 of 38, 24%) was documented based on identification of ≥50% methylated CpG sites in the CpG Island (Table 2). Reverse transcription-PCR was done to confirm up-regulation of candidate genes after 5-aza-dC treatment (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Candidate genes revealed by microarray analysis

| Gene ref ID | Gene name | Chromosome location |

Breast cell line methylation |

Normal breast tissue, n (%) |

Tumor breast tissue, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NM_000122 | ERCC3 | 2q21 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_000245 | MET | 7q31 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_000305 | PON2 | 7q21.3 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_000382 | ALDH3A2 | 17p11.2 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_000403 | GALE | 1p36-35 | Methylated in 2 of 4 | 3 of 3 (100) | |

| NM_000526 | KRT14 | 17q12-21 | Methylated in 3 of 4 | 3 of 3 (100) | |

| NM_001037 | SCN1B | 19q13.1 | Methylated in 1 of 4 | 0 of 3 (0) | 0 of 10 (0) |

| NM_001186 | BACH1 | 21p22.1 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_002371 | MAL | 2cen-q13 | Methylated in 4 of 4 | 0 of 6 (0) | 3 of 6 (50) |

| NM_004321 | KIF1A | 2q37.3 | Methylated in 4 of 4 | 1 of 6 (16) | 8 of 9 (89) |

| NM_006013 | RPL10 | Xq28 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_007152 | ZNF195 | 11p15.5 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_014242 | ZNF237 | 13q12 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_014454 | SESN1 | 6q21 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_014630 | ZNF592 | 15q25.3 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_014864 | FAM20B | 1p36.13-q41 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_015277 | NEDD4L | 18q21 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_015904 | EIF5B | 2p11-q11.1 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_017895 | DDX27 | 20q13.1 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_017945 | SLC35A5 | 3q13.2 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_020347 | LZTFL1 | 3p21.3 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_020990 | CKMT1 | 15q15 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_138340 | ABHD3 | 17p11.2 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_018245 | OGDHL | 10q11.23 | Methylated in 2 of 3 | 0 of 10 (0) | 8 of 25 (32) |

| NM_003359 | UGDH | 4p15.1 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_006339 | HMG20B | 19p13.3 | Methylated in 4 of 4 | 3 of 3 (100) | |

| NM_006815 | RNP24 | 12q24.31 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_012250 | RRAS2 | 11p15.2 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_012316 | KPNA6 | 1p35.1-34.3 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_015555 | ZNF451 | 6p12.1 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_005627 | SGK | 6q23 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_003896 | ST3GAL5 | 2p11.2 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_002014 | FKBP4 | 12p13.33 | Methylated in 3 of 4 | 0 of 10 (0) | 7 of 14 (50) |

| NM_000266 | NDP | Xp11.4 | Methylated in 4 of 4 | 2 of 4 (50) | |

| NM_002151 | HPN | 19q11-q13.2 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_007075 | WDR45 | Xp11.23 | Methylated in 2 of 4 | 3 of 3 (100) | |

| NM_016442 | ARTS-1 | 5q15 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_000267 | NF1 | 17q11.2 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_000332 | AXTN | 6p23 | Unmethylated | ||

| NM_003378 | VGF | 7q22 | Methylated in 4 of 4 | 0 of 6 (0) | 12 of 14 (86) |

NOTE: Forty-nine genes were up-regulated in breast cancer cell lines after treatment with 5-aza-dC. Bisulfite sequence analysis and/or MSP was done for each candidate gene in four breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, Hs578T, and BT-20). Genes that were methylated in cell lines were then bisulfite sequenced in 10 normal breast tissues and 10 breast tumors. GALE, KRT14, HMG20B, NDP, and WDR45 showed tissue-specific methylation, whereas MAL, FKBP4, KIF1A, OGDHL, and VGF were methylated in a cancer-specific manner.

Fig. 1.

Up-regulation of candidate genes after 5-aza-dC treatment. RNA was extracted from breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231after treatment with demethylating agent 5-aza-dC. Reverse transcription-PCR analysis shows up-regulation of MAL and VGF after treatment. GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Promoter hypermethylation in normal and primary tumor tissues

To determine if the methylated genes in cancer cell lines were cancer specific, we investigated promoter methylation in a limited number (n ~ 10 for tumors, n ~ 5 for normal tissues) of various primary tumors and age-matched normal tissues by bisulfite sequence analysis and/or MSP (Table 2). Of 9 genes that showed methylation in cell lines, promoter methylation was detected in 7 (78%) genes in primary tumor tissues. After testing corresponding age-matched normal tissues, 3 of these genes were identified to be methylated only in the neoplastic cells of primary tumors. Thus, 3 of 38 (8%) new potential cancer-specific methylated genes were identified.

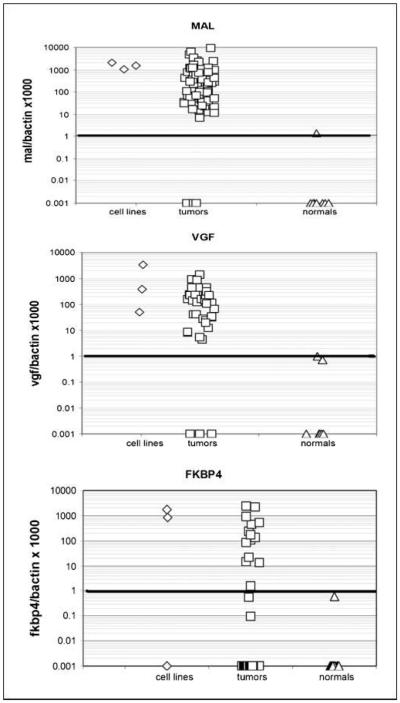

The three cancer-specific methylated genes identified were MAL, FKBP4, and VGF. To determine the frequency of methylation in a larger set of samples, primers and probes for quantitative MSP were designed for these genes based on bisulfite sequencing data. Breast tumors (~40) and normal breast tissues (~10) were tested for methylation of these individual genes. MAL was methylated in 38 of 40 (95%) breast tumors and 0 of 10 normals, whereas FKBP4 was methylated in 16 of 39 (41%) breast tumors and 0 of 10 normals. VGF was methylated in 31 of 35 (89%) breast tumors and was completely absent in normal tissues (Fig. 2; Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Quantitative MSP of breast cancer cell lines, tumors, and normal breast tissue. Scatter plots of quantitative MSP analysis of candidate gene promoters. Three cell lines (Hs.578T, MCF-7, and MDA-231), 10 normal breast tissue samples, and ~40 breast tumors were tested for methylation for each of the three genes by quantitative MSP. The relative level of methylated DNA for each gene in each sample was determined as a ratio of MSP for the amplified gene to ACTB and then multiplied by 1,000 for easier tabulation [(average value of triplicates of gene of interest / average value of triplicates of ACTB) × 1,000].The samples were categorized as unmethylated or methylated based on detection of methylation above a threshold set for each gene (horizontal bar). This threshold was determined by analyzing the levels and distribution of methylation, if any, in normal, age-matched tissues.

Table 3.

Methylation frequency of candidate genes in breast cancer cell lines, breast tumors, and normal breast tissue

| KIF1A | MAL | FKBP4 | VGF | OGDHL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer cell lines, n (%) | 4 of 4 (100) | 4 of 4 (100) | 3 of 4 (75) | 4 of 4 (100) | 2 of 3 (66) |

| Breast tumors, n (%) | 17 of 40 (43) | 38 of 40 (95) | 16 of 39 (41) | 31 of 35 (89) | 12 of 36 (33) |

| Normal breast tissue, n (%) | 2 of 10 (20) | 0 of 10 (0) | 0 of 10 (0) | 0 of 10 (0) | 0 of 10 (0) |

| P, tumor vs normal (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) | 0.28 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | <0.0001 | 0.04 |

NOTE: Methylation in cell lines was determined by bisufite sequencing of the four breast cancer cell lines. Methylation in normal breast tissue (n = 10) and breast tumors (n – 40) was determined by quantitative MSP. FKBP4 (P = 0.02), MAL (P < 0.0001), and VGF (P < 0.0001) showed significant differences in methylation between normal tissue and tumors.

Two of the genes identified by microarray analysis have been previously described by us (24) to show cancer-specific methylation in breast cancer. These genes were tested in this cohort of breast tissues with consistent results. OGDHL was methylated in 12 of 36 (33%) breast tumors and 0 of 10 normals. KIF1A was methylated in 17 of 40 (43%) breast tumors and at lower levels in 2 of 10 (20%) normals (Table 3).

Of 40 breast tumors that were tested for methylation of all five genes, all 40 (100%) had at least two of the five genes methylated. In 21 of 40 (53%) of the breast tumors cases, at least three of these genes were methylated and 10 of 40 (25%) showed methylation of four or more genes. Only two normal samples showed methylation in any of these genes (BN4 and BN7 for KIF1A; Table 4).

Table 4.

Methylation of multiple genes in breast cancer patients

| Tumors | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Age (y) | LN met | Stage | ER | PR | Her-2 | Class | KIF1A | MAL | FKBP4 | VGF | OGDHL |

| 1 | 65 | N | I | 1 | 0 | M | M | U | nd | U | ||

| 2 | 68 | N | I | 0 | 0 | M | M | U | nd | nd | ||

| 3 | 38 | N | I | 1 | 1 | M | M | U | M | nd | ||

| 4 | 46 | N | I | 1 | 1 | U | M | U | nd | U | ||

| 5 | 69 | N | I | 1 | 1 | U | M | M | U | U | ||

| 6 | 50 | N | I | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC | U | M | U | M | U |

| 7 | 69 | N | I | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A | U | M | U | M | U |

| 8 | 45 | N | I | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC | M | U | U | U | M |

| 9 | 55 | N | IIA | 0 | 0 | + | Her-2 | U | M | U | M | U |

| 10 | 60 | N | IIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A | M | M | U | M | M |

| 11 | 42 | N | IIA | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC | U | M | U | M | U |

| 12 | 65 | N | IIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A | U | M | U | M | U |

| 13 | 43 | N | IIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A | U | M | U | M | U |

| 14 | 52 | N | IIA | 1 | 1 | M | M | M | U | M | ||

| 15 | 60 | N | IIA | 0 | 0 | M | M | U | nd | U | ||

| 16 | 77 | N | IIA | 1 | 0 | U | M | M | M | U | ||

| 17 | 38 | N | IIA | 1 | 1 | M | M | U | M | U | ||

| 18 | 67 | N | IIA | 1 | 0 | U | M | M | M | U | ||

| 19 | 46 | N | IIA | 0 | 0 | M | M | M | M | M | ||

| 20 | 63 | N | IIA | 0 | 0 | U | M | U | M | U | ||

| 21 | 53 | Y | IIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A | M | M | U | M | M |

| 22 | 47 | Y | IIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A | U | M | U | M | U |

| 23 | 67 | Y | IIA | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC | U | M | M | M | M |

| 24 | 38 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | M | M | U | M | M | ||

| 25 | 53 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | U | M | M | nd | nd | ||

| 26 | 35 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | M | M | M | M | M | ||

| 27 | 53 | Y | IIB | 0 | 0 | M | M | M | U | M | ||

| 28 | 59 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | M | U | M | M | U | ||

| 29 | 50 | Y | IIB | 0 | 0 | U | M | U | M | nd | ||

| 30 | 41 | Y | IIB | 1 | 0 | 0 | LUM A | U | M | M | M | M |

| 31 | 59 | Y | IIB | 0 | 0 | U | M | M | M | U | ||

| 32 | 62 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | + | LUM B | U | M | U | M | U |

| 33 | 50 | Y | IIB | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A | U | M | U | M | M |

| 34 | 48 | Y | IIIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A | U | M | U | M | U |

| 35 | 35 | Y | IIIA | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC | U | M | U | M | U |

| 36 | 38 | Y | IIIA | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC | U | M | M | M | U |

| 37 | 50 | Y | IIIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A | U | M | U | M | U |

| 38 | 44 | Y | IIIA | 1 | 1 | 0 | LUM A | U | M | U | M | U |

| 39 | 80 | N | IIIB | 0 | 0 | M | M | nd | M | U | ||

| 40 | 55 | Y | IIIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | TNC | U | M | M | M | U |

| 41 | 53 | Y | IV | 0 | 0 | M | M | M | M | M | ||

| Normal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Age | LN met | Stage | KIF1A | MAL | FKBP4 | VGF | OGDHL |

| NA | NA | |||||||

| BN1 | 43 | U | U | U | U | U | ||

| BN2 | 43 | U | U | U | U | U | ||

| BN3 | 40 | U | U | U | U | U | ||

| BN4 | 43 | M | U | U | U | U | ||

| BN5 | 51 | U | U | U | U | U | ||

| BN6 | 46 | U | U | U | U | U | ||

| BN7 | 35 | M | U | U | U | U | ||

| BN8 | 53 | U | U | U | U | U | ||

| BN9 | 18 | U | U | U | U | U | ||

| BN10 | 23 | U | U | U | U | U | ||

| Markers | No. tumors methylated (%) |

|---|---|

| 2 | 40 of 40 (100) |

| 3 | 21 of 40 (53) |

| 4 or more | 10 of 40 (25) |

NOTE: Comparison of candidate gene methylation in breast cancer patients and breast tissues from disease-free women. Methylation was determined by quantitative MSP. Forty breast tumors were tested for methylation of all five genes. All 40 (100%) had at least two of the five genes methylated. In 21 of 40 (53%) of the breast tumors cases, at least three of these genes were methylated and 10 of 40 (25%) showed methylation of 4 or more genes. Only two normal samples showed methylation in any of these genes (BN4 and BN7 for KIF1A). Methylation of these genes was not subtype specific.

M, methylated; U, unmethylated; nd, not determined.

Discussion

Novel genes as markers for tumors

The “candidate gene” approach, where a tumor suppressor or previously reported methylated gene is tested in another type of cancer, has been used in most studies on DNA methylation in cancer. Our study involved identifying novel cancer-specific methylated genes based on a proven pharmacologic unmasking strategy in combination with a relatively large expression microarray. Among a large number of reexpressed candidate genes, we discovered three new cancer-specific methylated genes (MAL, FKBP4, and VGF).

The frequency of methylation of particular gene in primary tumors is less than that observed in cell lines (Table 3). This is consistent with previous studies (29-31). In artificial conditions, cell lines may have acquired methylation of some genes to provide a cell growth advantage. It is also possible that some of our tissue samples may have been contaminated with unmethylated DNA from normal surrounding cells despite microdissection. Furthermore, the microarray reexpression predicted the presence of up to 38 methylated genes, whereas experimentally, 9 methylated genes in cell lines were identified. We may have missed a few genes due to the analysis of limited promoter regions (~200-300 bp for most of the genes) by bisulfite sequencing or MSP.

FKBP4 expression did not increase substantially after treatment of cell lines with demethylating agents. In some methylated promoters, the addition of histone deacetylase inhibitors and other combinational approaches has led to a more robust increase in expression. In searching for markers of early cancer detection and prognosis, promoter methylation need not necessarily correlate with severely reduced expression (Fig. 1) as long as the methylation pattern is specific to neoplastic cells (Table 3) and is associated with clinically important information (24, 32).

In our cohort of breast tumors samples, MAL was found to be an excellent breast tumor marker, showing a high promoter methylation frequency (95%) in primary tumor samples. MAL is located at the 2cen-q13 locus of chromosome 2 and is a T-cell differentiation antigen. MAL expression was found to be down-regulated in patients harboring esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (33). MAL has also shown tumor-specific methylation in colon cancer (34). MAL is a candidate tumor suppressor gene because it has been shown that MAL gene expression in esophageal cancer suppresses motility, invasion, and tumorigenicity and enhances apoptosis through the Fas pathway (35). It is thus likely that MAL inactivation is an important step in the progression to cancer based on its high frequency of cancer-specific methylation in various tumor types and its tumor-suppressive activity.

Another gene found to be methylated in breast cancer is FKBP, with a moderate frequency (41%) and absence of methylation in normal breast tissues. FKBP4 is an immunophilin that possesses peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase activity and is a component of a subclass of steroid receptor complexes (36). It acts as a cochaperone that binds to heat shock protein 90 to regulate the maturation of steroid hormone receptor. Studies have shown that FKBP4 acts as an androgen receptor folding factor and, accordingly, plays an important role in the androgen receptor signaling pathway (36). The phenotype of male FKBP4-null mice is characterized by several defects in productive tissues consistent with androgen insensitivity. Knockdown of FKBP4 expression in HeLa cells decreases androgen receptor protein and reduces hormonal efficacy (37).

FKBP4 mRNA expression is increased MCF-7 cells (estrogen receptor positive) but not in MDA-MB-231 (estrogen receptor negative) cells (38). This increase in expression in MCF-7 cells is due to an increase in mRNA stability. This increase is activated by estradiols in MCF-7 (estrogen receptor positive) breast cancer cell lines (39). Ward et al. (38) also observed an increase in FKBP4 in breast tumors, which were all estrogen receptor positive; however, estrogen receptor–negative tumors were not tested. It is interesting that in our study, FKBP4 is not methylated in MCF-7 cells whereas is it methylated in MDA-MB-231 cells. It may be possible that FKBP4 methylation affects estrogen receptor expression and may thus have clinical relevance.

In our study, VGF has also proved to be an excellent candidate tumor marker. VGF was methylated in 89% of breast tumors and not in normal tissues. In another study, VGF was down-regulated in MDA-MB-231 after 24 hours of treatment with gemcitabine (accompanied by S-phase arrest) but up-regulated after 48 hours of treatment as cells went into apoptosis (40). Additional studies are needed to determine the role of VGF in cancer pathogenesis and response to various therapies.

Interestingly, WDR45 located on Xp11.23 was found to be methylated in normal breast tissue by bisulfite sequencing. Whereas aberrant methylation of X-chromosome genes can be easily identified in males, detection of methylation of these genes in female cells can be more difficult due to X-chromosome inactivation. Methylation status in breast tumors was not analyzed but methylation of X-chromosome genes in females may be distinguished by more sensitive methods. WD proteins are made up of highly conserved repeating units usually ending with Trp-Asp (WD). They are found in all eukaryotes but not in prokaryotes and regulate cellular functions such as cell division, cell fate determination, gene transcription, transmembrane signaling, mRNA modification, and vesicle fusion (41). Several human diseases have been recognized due to mutations in WD-repeat proteins (42). The involvement of WDR45 in breast cancer development remains to be determined.

The new methylation markers FKBP4, MAL, and VGF were studied independently and as a set to examine their role as potential diagnostic markers. Previous studies have shown that when multiple markers are examined as a set, sensitivity increases (6, 27, 43) as we found here. Two previously identified methylation markers (KIF1A and OGDHL; ref. 24) were added to the set to enhance sensitivity. All breast cancer tumors (40 of 40) harbored at least two methylated genes. For example, two breast cancer cases had methylated KIF1A whereas MAL was unmethylated (Table 4). In addition, although KIF1A was methylated in two normal breast tissue samples, the other four genes were not methylated in all normal tissues. These five markers seem to function well as a panel with only a minimal decrease in specificity. Methylation of these markers can be detected in all stage I tumors without lymph node metastasis (Table 4) as well as in advanced stages. Therefore, this panel of genes may be used in the development of early detection tests. This panel of genes is methylated in various subtypes of breast cancer: luminal A and B, Her-2 positive, and triple negative, as well as estrogen receptor–positive and estrogen receptor–negative breast cancers (Table 4), which is the hallmark of a good panel of markers.

There has been much discussion about which genes should be the focus of future efforts for methylation analysis. Our results suggest that many genes not previously confirmed to be involved in tumorigenesis are methylated at significant levels. These novel genes may provide additional clues to pathogenesis.

Finally, the presence of abnormally high DNA concentrations in the sera and plasma of patients with various malignant diseases has been described (44, 45). Recent publications have shown the presence of promoter hypermethylation of various bodily fluids including serum and nipple aspirate fluid DNA of breast cancer patients (5-8), which may offer an alternative approach to early detection approaches. Overall, these studies have established an association between the epigenetic alterations found in primary tumor specimens and in plasma, suggesting the potential utility of these alterations as surrogate tumor markers. The newly identified tumor markers here remain to be tested in serum or plasma from breast cancer patients. A blood test for breast cancer based on gene promoter methylation could augment current approaches such as mammography for the early detection of breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Cancer Institute grant U01-CA84986 and Oncomethylome Sciences, SA. The funding agency had no role in the design of the study, data collection, or analysis; in the interpretation of the results; in the preparation of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Argani is supported by The Johns Hopkins University Breast Specialized Program of Research Excellence grant CA88843. Dr. Hoque is supported by FAMRI Young Clinical Scientist Award, International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer and Career development award from Specialized Programs of Research Excellence in Cervical Cancer grants P50 CA098252.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest Under a licensing agreement between Oncomethylome Sciences, SA and The Johns Hopkins University, D. Sidransky is entitled to a share of royalty received by the University upon sales of diagnostic products described in this article. D. Sidransky owns Oncomethylome Sciences, SA stock, which is subject to certain restrictions under University policy. Dr. Sidransky is a paid consultant to Oncomethylome Sciences, SA and is a paid member of the company’s Scientific Advisory Board. The Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies is managing the terms of this agreement.

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–30. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elmore JG, Barton MB, Moceri VM, Polk S, Arena PJ, Fletcher SW. Ten-year risk of false positive screening mammograms and clinical breast examinations. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1089–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804163381601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elmore JG, Wells CK, Howard DH. Does diagnostic accuracy in mammography depend on radiologists’ experience? J Womens Health. 1998;7:443–9. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1998.7.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamill J, Campbell ID, Mayall F, Bartlett AS, Darlington A. Improved breast cytology results with near patient FNA diagnosis. Acta Cytol. 2002;46:19–24. doi: 10.1159/000326710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dulaimi E, Hillinck J, de Caceres I Ibanez, Al-Saleem T, Cairns P. Tumor suppressor gene promoter hypermethylation in serum of breast cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6189–93. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoque MO, Feng Q, Toure P, et al. Detection of aberrant methylation of four genes in plasma DNA for the detection of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4262–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krassenstein R, Sauter E, Dulaimi E, et al. Detection of breast cancer in nipple aspirate fluid by CpG island hypermethylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:28–32. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taback B, Giuliano AE, Lai R, et al. Epigenetic analysis of body fluids and tumor tissues: application of a comprehensive molecular assessment for early-stage breast cancer patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1075:211–21. doi: 10.1196/annals.1368.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baylin SB, Herman JG, Graff JR, Vertino PM, Issa JP. Alterations in DNA methylation: a fundamental aspect of neoplasia. Adv Cancer Res. 1998;72:141–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bird A. The essentials of DNA methylation. Cell. 1992;70:5–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90526-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leonhardt H, Cardoso MC. DNA methylation, nuclear structure, gene expression and cancer. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2000;(Suppl 35):78–83. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(2000)79:35+<78::aid-jcb1129>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esteller M. Cancer epigenetics: DNA methylation and chromatin alterations in human cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;532:39–49. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0081-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esteller M, Corn PG, Baylin SB, Herman JG. A gene hypermethylation profile of human cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3225–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dammann R, Yang G, Pfeifer GP. Hypermethylation of the cpG island of Ras association domain family 1A (RASSF1A), a putative tumor suppressor gene from the 3p21.3 locus, occurs in a large percentage of human breast cancers. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3105–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herman JG, Umar A, Polyak K, et al. Incidence and functional consequences of hMLH1 promoter hypermethylation in colorectal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6870–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Umbricht CB, Evron E, Gabrielson E, Ferguson A, Marks J, Sukumar S. Hypermethylation of 14-3-3σ (stratifin) is an early event in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:3348–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belinsky SA, Nikula KJ, Palmisano WA, et al. Aberrant methylation of p16(INK4a) is an early event in lung cancer and a potential biomarker for early diagnosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:11891–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esteller M, Sparks A, Toyota M, et al. Analysis of adenomatous polyposis coli promoter hypermethylation in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4366–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agrawal A, Murphy RF, Agrawal DK. DNA methylation in breast and colorectal cancers. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:711–21. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyamoto K, Fukutomi T, Akashi-Tanaka S, et al. Identification of 20 genes aberrantly methylated in human breast cancers. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:407–14. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esteller M. Epigenetic gene silencing in cancer: the DNA hypermethylome. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16 Spec No 1:R50–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone-modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:286–98. doi: 10.1038/nrg2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoque MO, Kim M, Ostrow K, et al. Genome-wide promoter analysis uncovers protions of the cancer “methylome” in primary tumors and cell lines. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2661–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoque MO, Lee CC, Cairns P, Schoenberg M, Sidransky D. Genome-wide genetic characterization of bladder cancer: a comparison of high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays and PCR-based microsatellite analysis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2216–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoque MO, Begum S, Topaloglu O, et al. Quantitation of promoter methylation of multiple genes in urine DNA and bladder cancer detection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:996–1004. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoque MO, Topaloglu O, Begum S, et al. Quantitative methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction gene patterns in urine sediment distinguish prostate cancer patients from control subjects. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6569–75. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tokumaru Y, Harden SV, Sun DI, Yamashita K, Epstein JI, Sidransky D. Optimal use of a panel of methylation markers with GSTP1 hypermethylation in the diagnosis of prostate adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5518–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tokumaru Y, Yamashita K, Osada M, et al. Inverse correlation between cyclin A1 hypermethylation and p53mutation in head and neck cancer identified by reversal of epigenetic silencing. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5982–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamashita K, Upadhyay S, Osada M, et al. Pharmacologic unmasking of epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor genes in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2002;2:485–95. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00215-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J, Nagpal J, Jeronimo C, et al. Hypermethylation of MCAM gene is associated with advanced tumor stage in prostate caner. Prostate. 2008;68:418–26. doi: 10.1002/pros.20709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kazemi-Noureini S, Colonna-Romano S, Ziaee AA, et al. Differential gene expression between squamous cell carcinoma of esophagus and its normal epithelium; altered pattern of mal, akr1c2, and rab11a expression. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1716–21. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i12.1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lind GE, Ahlquist T, Lothe RA. DNA hypermethylation of MAL: a promising diagnostic biomarker for colorectal tumors. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1631–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.003. author reply 1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mimori K, Shiraishi T, Mashino K, et al. MAL gene expression in esophageal cancer suppresses motility, invasion and tumorigenicity and enhances apoptosis through the Fas pathway. Oncogene. 2003;22:3463–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheung-Flynn J, Prapapanich V, Cox MB, Riggs DL, Suarez-Quian C, Smith DF. Physiological role for the cochaperone FKBP52 in androgen receptor signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1654–66. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin JF, Xu J, Tian HY, et al. Identification of candidate prostate cancer biomarkers in prostate needle biopsy specimens using proteomic analysis. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:2596–605. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward BK, Mark PJ, Ingram DM, Minchin RF, Ratajczak T. Expression of the estrogen receptor-associated immunophilins, cyclophilin 40 and FKBP52, in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;58:267–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1006390804515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar P, Mark PJ, Ward BK, Minchin RF, Ratajczak T. Estradiol-regulated expression of the immunophilins cyclophilin 40 and FKBP52 in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;284:219–25. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hernandez-Vargas H, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Julian-Tendero M, et al. Gene expression profiling of breast cancer cells in response to gemcitabine: NF-κB pathway activation as a potential mechanism of resistance. Breast Cancer ResTreat. 2007;102:157–72. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neer EJ, Schmidt CJ, Nambudripad R, Smith TF. The ancient regulatory-protein family of WD-repeat proteins. Nature. 1994;371:297–300. doi: 10.1038/371297a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li D, Roberts R. WD-repeat proteins: structure characteristics, biological function, and their involvement in human diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:2085–97. doi: 10.1007/PL00000838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belinsky SA, Liechty KC, Gentry FD, et al. Promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in sputum precedes lung cancer incidence in a high-risk cohort. Cancer Res. 2006;66:3338–44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsu HS, Chen TP, Hung CH, et al. Characterization of a multiple epigenetic marker panel for lung cancer detection and risk assessment in plasma. Cancer. 2007;110:2019–26. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lo YM. Circulating nucleic acids in plasma and serum: an overview. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;945:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.