Abstract

The present experiments examined the development and persistence of methamphetamine conditioned hyperactivity in Swiss-Webster mice. Experiments 1 and 2 examined the development of conditioned hyperactivity, varying the methamphetamine dose (0.25 – 2.0 mg/kg), the temporal injection parameters (continuous; Experiment 1 or intermittent; Experiment 2), and the comparison control group (saline; Experiment 1 or unpaired; Experiment 2). Experiment 3 examined the persistence of methamphetamine conditioned hyperactivity by comparing mice 1 (Immediate) or 28 (Delay) days after drug withdrawal. In each experiment, several behavioral measures (vertical counts, distance travelled and velocity) were recorded and temporal analyses conducted to assess methamphetamine conditioned hyperactivity. In Experiments 1 and 2, it was found that methamphetamine conditioned hyperactivity was 1) dose-dependent, 2) detected early in the session, 3) detected by a behavioral measure indicative of general activity (i.e., distance travelled), and 4) varied as a function of the number of conditioning sessions. In Experiment 3, it was found that conditioned hyperactivity persisted for 28 days, though was weakened by non-associative factors, following methamphetamine withdrawal. Collectively, these results suggest that conditioned hyperactivity to methamphetamine is robust and persists following prolonged periods of drug withdrawal in mice. Furthermore, these results are consistent with an excitatory classical conditioning interpretation of conditioned hyperactivity.

Keywords: behavior, conditioning, development, dose, hyperactivity, methamphetamine, persistence, withdrawal, mouse

Introduction

Repeated administration of psychostimulant drugs such as amphetamine or methamphetamine result in an enhanced responsiveness to the drug, a phenomenon known as behavioral sensitization, and reflects, at least in part, the unconditioned (i.e., pharmacological) action of the drug (Robinson and Becker 1986 for a review). Furthermore, behavioral sensitization following repeated psychostimulant administration has been used extensively as an animal model of drug addiction (for a review of preclinical animal studies see Vanderschuren and Kalivas 2000) and theorized as a neurobiological process that underlies drug addiction in people (Robinson and Berridge 1993; see Robinson and Berridge 2008 for a recent review of the incentive sensitization theory of drug addiction).

Numerous subject (e.g., strain and sex) and experimental factors have been identified that influence the development and persistence of behavioral sensitization to psychostimulants in rodents (see Robinson and Becker 1986 for a review). The training psychostimulant dose is one such experimental factor that influences the development of behavioral sensitization. Generally speaking, acute administration of low-to-moderate doses of amphetamine (0.25 – 1.0 mg/kg) or methamphetamine (0.3 – 2.0 mg/kg) produces an increase in horizontal and vertical activity whereas acute administration of high doses of amphetamine (e.g., 10 mg/kg) or methamphetamine (> 3.0 mg/kg) produce stereotypy (e.g., repetitive head and limb movement, sniffing and licking; see Segal and Kuczenski 1994 for a review; Gentry et al., 2004; Hall et al., 2008). With repeated administration of low-to-moderate doses of amphetamine or methamphetamine, the increase in horizontal and vertical activity is augmented (see Segal and Kuczenski 1994 for a review; Hall et al., 2008). Repeated administration of high doses of methamphetamine (e.g., 4 mg/kg) similarly results in augmented stereotypy (Hirabayashi and Alam 1981).

Temporal factors are other important experimental parameters that have been shown to influence the development and persistence of psychostimulant sensitization (see Robinson and Becker 1986 for a review). For example, it has been shown that intermittent administration of amphetamine or methamphetamine produces greater behavioral sensitization than continuous administration (Post 1980; Hirabayashi and Alam 1981). Hirabayashi and Alam (1981) found that intermittent administration (3 – 4 or 7 days apart) of methamphetamine (e.g., 2.0 mg/kg) in mice for 10 days produced more robust behavioral sensitization compared to when the methamphetamine was administered continuously. Other work has shown that lengthening the time of drug withdrawal enhances behavioral sensitization (Hitzeman et al., 1980; Kolta et al., 1985). For example, Kolta et al. (1985) observed more robust behavioral sensitization following 15 or 30 days of withdrawal from continuous amphetamine administration compared to 3 days of withdrawal. Additionally, the pharmacological, sensitized response, following continuous administration of methamphetamine (2 or 4 mg/kg), has been shown to persist for up to 2 months following drug withdrawal; however, no enhancement was detected (Hirabayashi and Alam 1981).

While behavioral sensitization reflects, in part, an unconditioned (i.e., pharmacological) action of psychostimulants, the enhanced responsiveness to the drug also reflects non-pharmacological, associative learning processes (i.e., classical conditioning; see Anagnostaras and Robinson 1996 for a discussion of the role of classical conditioning in behavioral sensitization). That is, following repeated pairings of the environment (locomotor activity chamber; conditioned stimulus - CS) with the locomotor-activating effects of the drug (e.g., methamphetamine; unconditioned stimulus - US), the chamber itself will elicit an increase in activity (i.e., a conditioned hyperactive response; conditioned response - CR) relative to a control group. Interestingly, the contribution of associative learning processes to drug sensitization (for recent reviews see Bradberry 2007; Leyton 2007) and drug addiction in people (Robinson and Berridge 1993; see Robinson and Berridge 2008 for a recent discussion of the role of conditioned stimuli within the incentive sensitization theory of drug addiction) has been suggested.

The training psychostimulant dose not only affects the development of the pharmacological, sensitized response, but also appears to influence the development of conditioned hyperactivity. Both low-to-moderate doses of amphetamine or methamphetamine have been shown to produce conditioned hyperactivity in rats (Tilson and Rech 1973; Alam 1981; Schiff 1982; Mazurski and Beninger 1987) or mice (Itzhak 1997; Itzhak and Martin 2000). For example, Bevins and Peterson (2004) examined the development of methamphetamine conditioned hyperactivity in rats, as defined by the total number of photo beam breaks, following a range of doses (0.0625 – 1.0 mg/kg). They found that moderate methamphetamine doses (0.25 – 1.0 mg/kg) produced conditioned hyperactivity. Along similar lines, Hall et al (2008) found that moderate methamphetamine doses (0.5 and 1.0 mg/kg) produced conditioned hyperactivity in rats, as measured by distance travelled and vertical activity (i.e., rearing). Using higher amphetamine doses (0.8 – 4.7 mg/kg), Schiff (1982) found that these amphetamine doses produced conditioned hyperactivity, as measured by various behaviors indicative of stereotypy (i.e., head bobbing and sniffing) and general activity (horizontal activity and rearing).

With the exception of the CS-US interval (Pickens and Crowder 1967), little research has systematically explored temporal injection parameters in the development and persistence of psychostimulant conditioned hyperactivity. A number of studies have shown that conditioned hyperactivity is detected following continuous amphetamine (Pickens and Crowder 1967; Tilson and Rech 1973; Gold et al., 1988) or methamphetamine (Itzhak 1997; Itzhak and Martin 2000; Bevins and Peterson 2004; Hall et al., 2008) administration; and intermittent administration of amphetamine has produced conditioned hyperactivity in rats (Mazurski and Beninger 1987). Importantly, in most studies examining the persistence of conditioned hyperactivity following psychostimulant administration the test for conditioned hyperactivity occurs shortly after drug withdrawal (1 – 4 days) (Tilson and Rech 1973; Mazurski and Beninger 1987; Gold et al., 1988; Itzhak 1997; Itzhak and Martin 2000; Bevins and Peterson 2004; Hall et al., 2008). Interestingly, only a few studies have examined conditioned hyperactivity following longer periods of drug withdraw and they have found that the response persists. For example, Borgkvist et al. (2008) found that conditioned hyperactivity was not diminished following 28 days of withdrawal from morphine.

The primary purpose of the present experiments was to characterize behaviorally, using a number of measures, the development and persistence of the conditioned hyperactivity to methamphetamine in Swiss-Webster mice. To date, the majority of psychostimulant conditioned hyperactivity experiments have been done using rats as experimental subjects, with fewer studies employing mice, particularly the Swiss-Webster strain (Itzhak 1997; Itzhak and Martin 2000). Methamphetamine-conditioned hyperactivity has been observed in Swiss-Webster mice; however, only a single training methamphetamine dose (1.0 mg/kg) and a single behavioral measure (ambulatory counts) were utilized in the experiment (Itzhak 1997). To our knowledge, methamphetamine-conditioned hyperactivity in Swiss-Webster mice has not been systematically examined. Thus, to this end, we behaviorally characterized the development of conditioned hyperactivity across a wide, methamphetamine dose-response range (0.25 – 2.0 mg/kg), varying the temporal injections parameters (continuous; Experiment 1 or intermittent; Experiment 2), and the comparison control group (saline; Experiment 1 or unpaired; Experiment 2). Finally, we behaviorally characterized the persistence of the methamphetamine-conditioned hyperactive response following sensitization to a single methamphetamine dose (1 mg/kg; Experiment 3). In this latter experiment, we also examined the persistence of the pharmacological aspect of methamphetamine sensitization. A multiple-measures approach was taken, as certain measures may be more sensitive in detecting contextually-conditioned effects (Bevins et al., 1997). Thus, in all experiments, measures indicative of rearing (vertical counts), speed (velocity) and overall activity (distance travelled) were electronically recorded. Due to the relatively low-to-moderate methamphetamine doses chosen, it was anticipated that little stereotypy would be observed. Furthermore, in order to determine the temporal topography of the methamphetamine conditioned hyperactive response, time course analyses were performed on all behaviors in each experiment.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 96 male Swiss Webster mice, obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC), were used in the experiments. At the start of the experiment, the mice weighed approximately 30–40 g. Mice were group housed (four/tub) in translucent Polysulfone tubs measuring 157.3 × 71 × 210.4 cm (length × width × height), lined with paper bedding, and contained within a ventilated-caging system (FA72-UD-WB, Alternative Design Mfg, Siloam Springs, AR) which cycled 30 air changes/hour into the tubs. The room containing the ventilated cages was maintained at ~ 21 degrees Celsius and the lights were automatically controlled on a 12:12 light/dark cycle. All experiments were conducted during the light phase of the cycle. The mice were allowed free access to food (Purina Rodent Chow) and water for the duration of the experiment. These experiments were approved by the Dickinson College Animal Care and Use Committee. All experiments conform to the guidelines established by the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996 Edition) and the APA Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. In all experiments, mice acclimated to the animal colony for 1 week after arrival. During the acclimation period, mice were handled for 1 min for 4 consecutive days.

Apparatus

Eight open-field activity chambers (MED-OFA-510, Med-Associates, Burlington, VT) were used. The compartment walls were constructed with Plexiglas and the inside dimensions were 27.9 cm × 27.9 cm (length × width). For the duration of the recording period, a home-made Plexigas cover (with holes) was placed over the tops of the chambers. Locomotor activity was determined by three, 16-beam I/R arrays (X, Y and Z axes) and photo beam breaks were recorded by a personal computer (MED-PC Activity Software) located in the same room as the chambers. The chambers were cleaned with a disinfectant solution (Precise QTB/Caltech, Midland, MI) following each 30 minute (min) locomotor activity session. The locomotor activity chambers were housed in sound-attenuating chambers (MED-OFA-022, Med-Associates, Burlington, VT) measuring 22 × 14 × 15 inches (length × width × height). The sound-attenuating chambers were equipped with two small lights and fans. The fans provided an ambient background noise of ~ 70 dB. In order to provide an olfactory cue, a small capful of pure anise (McCormick, Hunt Valley, MD) was placed outside the activity chambers, but within the sound-attenuating cubicles, at the beginning of each locomotor activity session.

Behavioral Measures

The following behavioral measures were recorded in each experiment. These behaviors were electronically recorded using Med-PC software (Med-PC Activity Monitor, Version 5) and were defined by the breakage of photo beams. The definitions below are taken from the owner’s manual that accompanies the Med-PC Activity Monitor (Version 5) program (see Page 59, Med-PC Activity Monitor 2004).

Vertical Counts. The number of periods of continuous beam breaks reported by the “Z” I/R array.

Velocity (cm/sec). The average velocity for each data block and total for the session.

Distance Travelled. Distance travelled is defined by the combination of Box Size and Resting Delay parameters. This creates a threshold, and the subject must move a specified distance (Box Size) in a defined period of time (Resting Delay) to maintain ambulatory movement status.

Experiment 1. Development of Methamphetamine Conditioned Hyperactivity Following 8 Continuous Conditioning Sessions

Following the acclimation period, the experiment consisted of three phases: habituation, conditioning and test. The habituation phase lasted one session and all mice were given an injection (SC) of vehicle (physiological saline) before placement in the locomotor activity chambers for a 30-min period. Twenty-four hours (h) after the habituation session, the conditioning phase began. During the conditioning phase, mice (n = 9–10/dose) received injections (SC) of either vehicle (physiological saline) or methamphetamine (0.5, 1.0 or 2.0 mg/kg) and were placed immediately in the locomotor activity chambers for 30-min periods on 8 consecutive conditioning sessions, spaced 24 h apart. Twenty-four h following the last conditioning session, a test for conditioned hyperactivity session was conducted in which all mice received an injection of vehicle (SC) and were placed immediately in the locomotor activity chambers for a 30-min period.

Experiment 2. Development of Methamphetamine Conditioned Hyperactivity Following 4 Intermittent Conditioning Sessions

Following the acclimation period, the experiment consisted of two phases: conditioning and test. Similar to Experiment 1, the conditioning phase lasted 8 sessions. On 4 alternating days (Chamber Days) of the conditioning phase, mice received injections (SC) of either vehicle (physiological saline; paired and unpaired) or methamphetamine (0.25, 0.5 or 1.0 mg/kg; paired) before placement in the locomotor activity chambers for 30-minute periods. On the 4 intervening days (Home Cage) of the conditioning phase, mice received injections (SC) of either vehicle (physiological saline; paired and unpaired) or methamphetamine (0.25, 0.5 or 1.0 mg/kg; unpaired) in their home cages. The injections on the intervening home cage days occurred in the animal colony. For paired groups (vehicle, 0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 mg/kg), 6 mice were assigned to each dose. For the unpaired groups (vehicle, 0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 mg/kg), only 2 mice were assigned to each dose. It was anticipated that unpaired mice would not differ in locomotor activity; consequently their data would be collapsed into a single unpaired control group (see Results). The paired vehicle group was similar to the vehicle control group in Experiment 1 and was included in order to compare the paired vehicle group to the unpaired control group in the present experiment. The test for conditioned hyperactivity occurred 1 day following the last home cage day. At this time, all mice were injected (SC) with vehicle immediately prior to placement in the locomotor activity chambers for a 30-min period.

Experiment 3. Persistence of Methamphetamine Conditioned Hyperactivity Following 4 Intermittent Conditioning Sessions

Following the acclimation period, similar to Experiment 2, the experiment consisted of 2 phases: conditioning and test. Mice (n = 6/group) were assigned to 1 of 4 groups: Paired-Immediate, Paired-Delay, Unpaired-Immediate, or Unpaired-Delay. During 4 alternating days (Chamber Days) of the conditioning phase, mice received injections (SC) of either vehicle (physiological saline; unpaired) or a single methamphetamine dose (1.0 mg/kg; paired) before placement in the locomotor activity chambers for 30-min periods. On the 4 intervening days (Home Cage) of the conditioning phase, mice received injections (SC) of either vehicle (physiological saline; paired) or methamphetamine (1.0 mg/kg; unpaired) in their home cages located in the animal colony. Tests for conditioned hyperactivity and methamphetamine sensitization occurred 1 or 2 days (Immediate), respectively, or 28 or 29 days (Delay), respectively, following the last home-cage day of the conditioning phase. During the tests for conditioned hyperactivity (Days 1 or 28), all mice received injections (SC) of vehicle (physiological saline) prior to placement in the locomotor activity chambers for 30-min sessions. During the tests for methamphetamine sensitization (Days 2 or 29), all mice received injections (SC) of methamphetamine (1.0 mg/kg) prior to placement in the locomotor activity chambers for 30-min sessions. Tests for conditioned hyperactivity preceded the tests for methamphetamine sensitization so that exposure to methamphetamine in the unpaired mice in the locomotor activity chamber during the methamphetamine sensitization tests did not complicate detection of the CR during the tests for conditioned hyperactivity.

Drugs

Methamphetamine HCl (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) was prepared in physiological saline and injected (subcutaneous, SC) at volume of 10 ml/kg (body weight). Doses of methamphetamine are expressed as the salt weight of the drug.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a standard, statistical program (PASW Statistics 17.0). In order to determine the temporal pattern of the conditioned hyperactive response in each experiment, the data were grouped in 5 min bins and subsequent time-course analyses were performed. In Experiments 1 and 2, each behavioral measure (distance travelled, vertical counts, and velocity) was subjected to a two-way (Dose × Session Minute) analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the test session for conditioned hyperactivity. Significant main effects or interactions of interest motivated follow-up one-way ANOVAs and post hoc Dunnett’s tests to explore differences at particular time points. In Experiment 3, each behavioral measure was subjected to a three-way Conditioning (Paired vs. Unpaired) × Time of Test (Immediate vs. Delay) × Session Minute ANOVA on the tests for conditioned hyperactivity or methamphetamine sensitization. Significant main effects or interactions of interest motivated follow-up one-way ANOVAs and independent-samples t tests to explore differences at particular time points. Unless otherwise stated, all statistical decisions were made at α level = 0.05 (two tailed).

Results

In all experiments, analyses of the velocity measure did not reveal any reliable group differences. Thus, statistical and graphical presentations of the results of this measure were omitted for the sake of brevity.

Experiment 1. Development of Methamphetamine Conditioned Hyperactivity Following 8 Continuous Drug Conditioning Sessions

Experimental error resulted in the elimination of two mice from the experiment. Therefore, the data for these subjects were removed and the data for only 38 subjects were analyzed.

Distance Travelled

The two-way ANOVA revealed a significant Dose × Session Minute interaction, F (15, 170) = 2.9, p < 0.001. Follow-up analyses revealed that all methamphetamine doses differed from the vehicle control dose during the first 5 min bin; however, only the lowest methamphetamine dose (0.5 mg/kg) differed from the vehicle control dose during the second 5-min bin, ps < 0.05. No other group differences were detected during any of the remaining session minutes (Figure 1, upper panel).

Figure 1. Test for Conditioned Hyperactivity in Experiment 1.

Distance travelled (cm) (upper panel) and the number of vertical counts (lower panel) on the test session. The symbols *, # and &denote significant differences between the low (0.5 mg/kg), moderate (1.0 mg/kg) and high (2.0 mg/kg) methamphetamine doses, respectively, and the vehicle control dose, p < 0.05.

Vertical Counts

The two-way ANOVA revealed a significant Dose × Session Minute interaction, F (15, 170) = 1.87, p < 0.05. Follow-up analyses revealed that the low (0.5 mg/kg) and high (2.0 mg/kg) methamphetamine doses differed from the vehicle control dose during the first 5-min bin, ps < 0.05. The moderate methamphetamine dose (1.0 mg/kg) also differed from the vehicle control dose, but this difference failed to reach significance, p = 0.073. Reliable differences between doses were not detected on any of the remaining session minutes (Figure 1, lower panel).

Experiment 2. Development of Methamphetamine Conditioned Hyperactivity Following 4 Intermittent Drug Conditioning Sessions

Distance Travelled

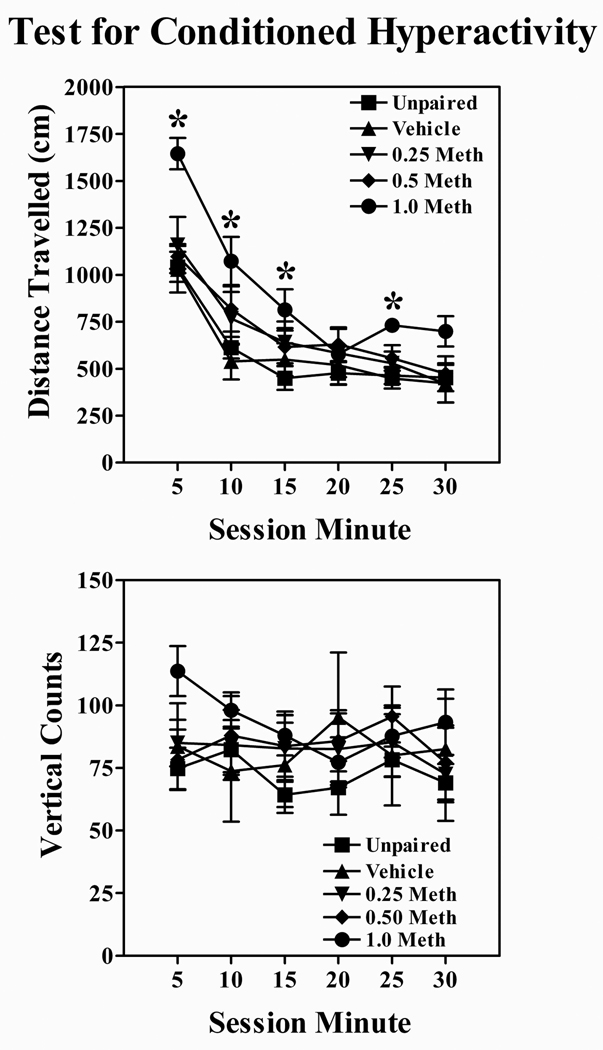

The two-way ANOVA revealed significant main effects of Dose and Session Minute, Fs > 3.6, ps < 0.05, and a significant Dose × Session Minute interaction, F (20, 135) = 2.4, p < 0.01. Follow-up analyses revealed that only the high methamphetamine dose (1.0 mg/kg) differed from the unpaired control group during Session Minutes 5, 10, 15 and 25, ps < 0.05 (Figure 2, upper panel).

Figure 2. Test for Conditioned Hyperactivity in Experiment 2.

Distance travelled (cm) (upper panel) and the number of vertical counts (lower panel) on the test session. Thesymbol * denotes a significant difference between the moderate (1.0 mg/kg) methamphetamine dose and the unpaired control group, p < 0.05.

Vertical Counts

A two-way ANOVA failed to detect any reliable differences with respect to dose, Fs < 1.1 (Figure 2, lower panel).

Experiment 3. Persistence of Methamphetamine Conditioned Hyperactivity Following 4 Intermittent Drug Conditioning Sessions

Tests for Conditioned Hyperactivity

Distance Travelled

The three-way ANOVA yielded significant main effects of Session Minute, F (5, 100) = 50.5, p < 0.001, Conditioning, F (1, 20) = 46.8, p < 0.001, Time of Test, F (1, 20) = 9.8, p < 0.01, and only a significant Conditioning × Session Minute interaction, F (5, 100) = 10.2, p < 0.001. Follow-up contrasts involving independent-samples t tests revealed that paired-immediate mice were more active than unpaired-immediate mice for the entire session whereas paired-delay mice were more active than their unpaired-delay counterparts for Session Minutes 5 – 25, ts (10) > 2.5, ps < 0.05 (Figure 3, upper left panel). The significant main effect of Time of Test, and the non-significant Conditioning × Time of Test interaction, suggests that mice tested after the 28-day drug withdrawal period (Delay) were less active than those mice tested 1 day after drug withdrawal (Immediate) regardless of their conditioning history. Indeed, follow-up independent samples t tests, conducted on the distance travelled of the entire 30-min session, revealed that delay mice were less active than their immediate counterparts, ts (10) > 2.1, ps ≤ 0.05, suggesting that the decrease in locomotor activity following the 28-day drug withdrawal period was due to non-associative factors (Figure 3, top right panel).

Figure 3. Test for Conditioned Hyperactivity in Experiment 3.

Distance travelled (cm) (upper panels) and the number of vertical counts (lower panels) during the entire 30-minute session (right panels) or in 5-min bins (left panels) for mice tested 1 (Immediate) or 28 (Delay) days following drug withdrawal. The symbols * and #denote significant differences between the paired-immediate and paired-delay mice, respectively, and their unpaired counterparts, p < 0.05. The brackets denote a significant difference between immediate mice and their delay counterparts, p < 0.05.

Vertical Counts

The three-way ANOVA yielded significant main effects of Session Minute, F (5, 100) = 5.6, p < 0.001, Conditioning, F (1, 20) = 12.5, p < 0.01, and Time of Test, F (1, 20) = 14.4, p = 0.001. Follow-up contrasts involving independent-samples t tests revealed that paired-immediate mice were more active than unpaired-immediate mice during the first 5 min of the session whereas paired-delay mice were more active than their unpaired-delay counterparts for Session Minutes 5 – 20, ts (10) > 2.25, ps < 0.05 (Figure 3, lower left panel). Similar to the distance travelled measure, the significant main effect of Time of Test, and the non-significant Conditioning × Time of Test interaction, suggest that mice tested after the 28-day drug withdrawal period (delay) were less active than those mice tested 1 day after drug withdrawal (immediate) regardless of their conditioning history. However, follow-up independent samples t tests, conducted on the entire 30-min session, revealed that only unpaired-delay mice were less active than their unpaired-immediate counterparts, t (10) = 3.45, p < 0.01: paired-delay mice did not differ from their paired-immediate counterparts, p = 0.08 (Figure 3, lower right panel).

Tests for Methamphetamine Sensitization

Distance Travelled

The three-way ANOVA yielded only a significant main effect of Session Minute, F (5, 100) = 5.5, p < 0.001, Conditioning, F (1, 20) = 6.4, p < 0.05, and Conditioning × Session Minute interaction, F (5, 100) = 2.9, p < 0.05. Follow-up contrasts involving independent-samples t tests revealed that paired-immediate mice were more active than unpaired-immediate mice during Session Minutes 10 – 30, ts (10) > 2.2, ps < 0.05, whereas paired-delay mice did differ from their unpaired-delay counterparts at any time point. Neither the main effect of Time of Test nor the Conditioning × Time of Test interaction was significant. The significant main effect of Conditioning, combined with the non-significant Conditioning × Time of Test interaction, suggests that paired mice were more active than unpaired mice regardless as to when they were tested (Figure 4, upper panel).

Figure 4. Test for Methamphetamine Sensitization in Experiment 3.

Distance travelled (cm) (upper panel) and the number of vertical counts (lower panel) for mice tested 1 (Immediate) or 28 (Delay) days following drug withdrawal. The symbols *and #denote significant differences between the paired-immediate and paired-delay mice, respectively, and their unpaired counterparts, p < 0.05.

Vertical Counts

The three-way ANOVA yielded significant main effects of Conditioning, F (1, 20) = 5.5, p < 0.05, and Time of Test, F (1, 20) = 10.4, p < 0.01. Follow-up contrasts involving independent-samples t tests revealed that paired-immediate mice were more active than unpaired-immediate mice during Session Minutes 5 and 10, ts (10) > 2.2, p < 0.05, whereas paired-delay mice did not differ from the unpaired-delay mice on any time point. The significant main effect of Conditioning suggests that paired mice were more active than unpaired mice, and the significant main effect of Time of Test suggests that immediate mice were more active than their delay counterparts. The failure to detect a significant Conditioning × Time of Test interaction suggests that the decrease in locomotor activity in the delay mice compared to the immediate mice was due to non-associative factors (Figure 4, lower panel).

Discussion

In Experiment 1, we found that all methamphetamine doses tested (0.5 – 2.0 mg/kg) produced conditioned hyperactivity, as detected by the distance travelled measure. Moreover, the conditioned hyperactive response was more pronounced very early in the session (i.e., the first 5 min). The vertical counts measure detected conditioned hyperactivity only for the low (0.5 mg/kg) and high (2.0 mg/kg) methamphetamine doses, with the response again being confined to the very early part of the session. (This measure also suggested conditioned hyperactivity at the moderate methamphetamine dose, 1.0 mg/kg, but this difference failed to reach statistical significance, p = 0.073.) These results are similar to the Bevins and Peterson (2004) study, which found that methamphetamine produced conditioned hyperactivity at moderate methamphetamine doses (0.25 – 1.0 mg/kg), as measured by the total number of photo beam breaks, following 8 continuous conditioning sessions. The results of the present experiment are also consistent with the study by Itzhak (1997) which found that a moderate methamphetamine dose (1.0 mg/kg) produced conditioned hyperactivity, as measured by ambulatory counts, in Swiss-Webster mice; however, the Itzhak (1997) study did not assess the temporal pattern of the CR. The results of the present experiment add to the methamphetamine conditioned hyperactivity literature, showing the temporal pattern of the CR, a temporal conditioned hyperactivity pattern observed by other drugs of abuse (e.g., amphetamine, Mazurski and Beninger 1987). Thus, when the results of Experiment 1 are viewed in tandem with the results of previous studies, they suggest that moderate methamphetamine doses produce conditioned hyperactivity and behavioral measures indicative of overall activity (e.g., distance travelled) and rearing (e.g., vertical counts) are sensitive in detecting such conditioned hyperactivity early in the session in mice.

In Experiment 2, we found methamphetamine produced a conditioned hyperactive response in mice in a dose-dependent manner, with only the high methamphetamine dose (1.0 mg/kg) being effective. Lower methamphetamine doses (0.25 and 0.5 mg/kg) failed to produce conditioned hyperactivity. Moreover, only the distance travelled measure detected the conditioned hyperactive response and the time course analysis revealed that the response persisted for most of the 30-min session. Neither the vertical counts measure nor the velocity measure detected conditioned hyperactivity. The dose-dependent nature of the conditioned hyperactive response partially resembles the findings by Bevins and Peterson (2004). In that study, Bevins and Peterson (2004) found that a very low methamphetamine dose (0.0625) failed to produce conditioned hyperactivity in rats whereas low-to-moderate methamphetamine doses (0.25 – 1.0 mg/kg) produced it. The reason that Bevins and Peterson (2004) found a conditioned hyperactive response following low-to-moderate methamphetamine doses (0.25 – 0.5 mg/kg) and the present study did not most likely stems from either species differences (rat vs. mouse) and/or differences in the number of conditioning sessions (8 vs. 4) between the two studies: the latter variable has been shown to influence the magnitude of the conditioned hyperactive response (Michel et al., 2003).

Previous research that has demonstrated methamphetamine conditioned hyperactivity in mice employed a vehicle control condition (Itzhak 1997). In Experiment 2, however, we employed an explicitly unpaired control group, a control group that has been widely used in conditioned hyperactivity experiments and is generally thought of as a better control group than the vehicle control group, as it equates the experimental and control groups with respect to their pharmacological histories (see Bardo and Bevins 2000 for a discussion of appropriate control groups in classical conditioning paradigms involving contextual stimuli and drugs). The finding that mice that were administered the high methamphetamine dose (1.0 mg/kg) were more active than the unpaired mice, and the latter mice did not differ from vehicle control mice, provides strong evidence that the increase in locomotor activity in paired mice stems from associative learning processes.

Direct comparisons between Experiments 1 and 2 are made difficult by the several parametric differences between the two experiments: the experiments differed in terms of 1) the temporal injections parameters (continuous; Experiment 1 or intermittent; Experiment 2), 2) the number of conditioning sessions (8; Experiment 1 or 4; Experiment 2), and 3) the comparison control group (saline; Experiment 1 or unpaired; Experiment 2). Despite these parametric differences, the results of these two experiments suggest a number of conclusions. First, robust conditioned methamphetamine hyperactivity can be obtained following either continuous (Experiment 1) or intermittent (Experiment 2) conditioning. Second, relatively moderate methamphetamine doses (0.5 – 2.0 mg/kg) produce conditioned hyperactivity, as detected by behavioral measures indicative of non-stereotypic behaviors (i.e., general locomotor activity and rearing). In neither experiment did the velocity measure detect conditioned hyperactivity. Thus, while it has been shown that velocity can detect the unconditioned (pharmacological), locomotor-activating effect of psychostimulants (Flagel and Robinson 2007), this measure is not sensitive enough to detect the conditioned hyperactive effects of psychostimulants. Third, the number of conditioning sessions influences the development of the CR, an observation consistent with other conditioned hyperactivity studies (Michel et al., 2003). For example, Michel et al. (2003) has shown that conditioned hyperactivity is detected following 6 or 12, but not 3, conditioning sessions. Moreover, the CR was most robust following 12, as compared to 6, conditioning sessions in this study.

To our knowledge, no studies have examined the persistence of methamphetamine conditioned hyperactivity in mice. In Experiment 3, we found that conditioned hyperactivity persisted following 28 days of drug withdrawal. Similar to Experiment 2, the distance travelled measure detected conditioned hyperactivity when mice were tested 1 day (Immediate) or 28 days (Delay) following drug withdrawal. Furthermore, the vertical counts measure did not detect a difference between paired and unpaired mice when tested 1 day (Immediate) after drug withdrawal, similar to Experiment 2. However, unlike Experiment 2, the vertical counts measure detected differences between paired and unpaired mice when tested 28 days following drug withdrawal (Delay), suggesting that this measure can detect conditioned hyperactivity under certain temporal testing conditions.

The finding in the present report that conditioned hyperactivity persisted for 28 days following drug withdrawal is consistent with a previous conditioned hyperactivity study (Borgkvist et al., 2008). However, unlike Borgkvist et al (2008), we found that the CR was diminished following the 28-day withdrawal period and that the diminution of the CR was due to non-associative factors, as a diminution in activity also was observed in unpaired mice following a 28-day period of drug withdrawal. At present, it is unclear as to why the CR was diminished in Experiment 3. However, it should be noted that with respect to another, contextually-mediated classical conditioning paradigm involving drugs (i.e., conditioned place preference; CPP), studies have found that the CR is diminished (Lu et al., 2000a,b, 2001), remains the same (Mucha and Iversen 1984; Mueller and Stewart 2000; Mueller et al., 2002), or is enhanced (Shaham and Hope, 2005; Lu et. al, 2006; see below for an elaboration on this point) following prolonged periods of drug withdrawal. These latter results suggest that the vagaries of the experimental parameters may influence the strength of the CR following prolonged periods of drug withdrawal in contextually-mediated classical conditioning paradigms.

In Experiment 3, we also found that the pharmacological, sensitized response persisted following 28 days of drug withdrawal. However, similar to the CR, the pharmacological, sensitized response was diminished due to non-associative factors. This latter result was surprising, as a number of studies have shown that the pharmacological, sensitized response is enhanced following periods of drug withdrawal more than 14 days (Hitzeman et al., 1980; Kolta et al., 1985; see Robinson and Becker 1986 for a review). For example, Kolta et al (1985) observed more robust behavioral sensitization following 15 or 30 days, compared to 3 days, of withdrawal from continuous amphetamine administration. The failure to detect an enhancement in behavioral sensitization following the 28-day withdrawal period may be unique to methamphetamine. Indeed, a previous study found that continuous administration of methamphetamine (2 or 4 mg/kg) persisted for up to 2 months following drug withdrawal; however, no enhancement was detected (Hirabayashi and Alam 1981). Alternatively, the failure to detect an enhanced sensitized response to methamphetamine may stem from the dose of methamphetamine selected (e.g., 1.0 mg/kg) and/or the temporal parameters chosen (e.g., 4 intermittent conditioning sessions). These ideas are speculative and require further empirical support.

Theoretical Implications

The role of associative learning processes in the development and persistence of behavioral sensitization has been a matter of debate. Traditionally, the increase in locomotor activity following drug conditioning observed either when the activity chamber alone is presented in the absence of the psychostimulant drug, as in Experiments 1 and 2 of the present report, or when the test for pharmacological sensitization compares animals that underwent sensitization in the test environment to animals that did not, as in the methamphetamine challenge test days of Experiment 3, is interpreted to reflect associative learning processes. With respect to conditioned hyperactivity, this interpretation has been termed the “excitatory classical conditioning hypothesis” (see Tirelli et al., 2005 for recent discussion of this hypothesis as it pertains to conditioned hyperactivity). However, other interpretations have been offered (e.g., see Ahmed et al., 1995 for a review of a habituation account of conditioned hyperactivity). Indeed, it has been argued that the increase in locomotor activity at the time of test for conditioned hyperactivity does not reflect a classically conditioned response; and hence, does not stem from associative learning processes (Ahmed et al., 1995, 1998; Tirelli et al., 2003, 2005). Moreover, it has been argued that associative learning processes do not contribute to the increase in locomotor activity at the time of a pharmacological challenge to test for behavioral sensitization (Tirelli et al., 2005).

The results of the present experiments lend support to the excitatory classical conditioning interpretation and buttress the claim that associative learning processes contribute to behavioral sensitization. First, methamphetamine conditioned hyperactivity was dose-dependent under certain experimental conditions (Experiment 2). Second, the methamphetamine conditioned hyperactive response was more robust following 8 (Experiment 1) as compared to 4 (Experiment 2) conditioning sessions. (Admittedly, as previously noted, Experiments 1 and 2 differed in other ways beyond the number of sessions that limit direct comparisons between the experiments). Third, conditioned hyperactivity persisted for up to 28 days following methamphetamine withdrawal (Experiment 3). These observations are similar to the results of other conditioned hyperactivity studies that have shown that the CR varies as a function of the 1) intensity of the US (Michel and Tirelli 2002), and 2) the number of conditioning sessions (Michel et al., 2003), and 3) the CR persists over time (Tirelli et al., 2005), well-established characteristics of classical conditioning (Domjan 2010).

In sum, the present experiments found that various factors influenced the development of the conditioned hyperactive response following methamphetamine administration in Swiss-Webster mice. Furthermore, the conditioned hyperactive response persisted, though weakened by non-associative factors, for 28 days following methamphetamine administration. Behavioral measures of general activity (e.g., distance travelled) and rearing (e.g., vertical counts) detected conditioned hyperactivity, though these measures were differentially sensitive in detecting such activity, further stressing the need for multiple dependent measures when assessing contextually-conditioned effects (Bevins et al., 1997). While the nature of the increase in locomotor activity at the time of test for conditioned hyperactivity, and the contribution of associative learning processes to behavioral sensitization, remains a matter of debate, the preponderance of evidence supports an excitatory classical conditioning interpretation. On balance, this evidence suggests that the conditioned hyperactive response follows principles of classical conditioning. For example, the conditioned hyperactive response 1) weakens when the conditioned environment is presented repeatedly in the absence of the drug (i.e., extinction; Hinson and Poulos 1981; Michel et al., 2003), 2) is influenced by the CS-US interval (Pickens and Crowder 1967), and 3) weakens when the contextual cues are repeatedly presented, in the absence of the US, prior to conditioning (i.e., the CS pre-exposure effect; Drew and Glick 1988). The novel results of the present experiments lend further theoretical support for the excitatory classical conditioning interpretation of conditioned hyperactivity.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Margo Schade, Jaime Moellman, Neil Devoe, Cemre Eren and Jonathan Danquah for their assistance in collecting the data associated with this manuscript. The authors also wish to thank Dr. Meredith Rauhut for critically reading an early draft of the manuscript.

Supported by a grant (USPHS DA019866) awarded from the National Institutes of Health to A. S. Rauhut and funds provided by the Department of Psychology, Dickinson College.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmed SH, Cador M, Le Moal M, Stinus L. Amphetamine-induced conditioned activity in rats: Comparison with novelty-induced activity and role of the basolateral amygdale. Behav Neurosci. 1995;109:723–733. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.109.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed H, Stinus L, Cador M. Amphetamine-induced conditioned activity is insensitive to perturbations known to affect Pavlovian conditioning responses in rats. Behav Neurosci. 1998;112:1167–1176. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.5.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MR. Enhancement of Motor- Accelerating Effect Induced by Repeated Administration of Methamphetamine in Mice: Involvement of Environmental Factors. J Pharmacol. 1981;31:897–904. doi: 10.1254/jjp.31.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostaras SG, Robinson TE. Sensitization to the psychomotor stimulant effects of amphetamine: Modulation by associative learning. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110:1397–1414. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.6.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Bevins RA. Conditioned place preference: What does it add to our preclinical understanding of drug reward? Psychopharmacology. 2000;153:31–43. doi: 10.1007/s002130000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevins RA, Peterson JL. Individual Differences in Rats’ Reactivity to Novelty and the Unconditioned and Conditioned Locomotor Effects of Methamphetamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevins RA, McPhee JE, Rauhut AS, Ayres JBB. Converging evidence of conditioning with immediate shock: Importance of shock potency. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process. 1997;23:312–324. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.23.3.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgkvist A, Valjent E, Santini E, Hervé D, Girault J-A, Fisone G. Delayed, context- and dopamine D1 receptor-dependent activation of ERK in morphine-sensitized mice. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradberry CW. Cocaine sensitization and dopamine mediation of cue effects in rodents, monkeys, and humans: Areas of agreement, disagreement, and implications for addiction. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:705–717. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0561-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domjan M. The Principles of Learning and Behavior. CA: Wadsworth/Cengage learning; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Drew KL, Glick SD. Characterization of the associative nature of sensitization to amphetamine-induced circling behavior and of the environment dependent placebo-like response. Psychopharmacology. 1988;95:482–487. doi: 10.1007/BF00172959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Robinson TE. Quantifying the psychomotor activating effects of cocaine in the rat. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:297–302. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3281f522a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry WB, Ghafoor AU, Wessinger WD, Laurenzana EM, Hendrickson HP, Owen SM. (+)-Methamphetamine-induced spontaneous behavior in rats depends on route of (+)Meth administration. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:751–760. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LH, Swerdlow NR, Koob GF. The role of mesolimbic dopamine in conditioned locomotion produced by amphetamine. Behav Neurosci. 1988;102:544–552. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DA, Stanis JJ, Avila HM, Gulley JM. A comparison of amphetamine- and methamphetamine-induced locomotor activity in rats: Evidence for qualitative differences in behavior. Psychopharmacology. 2008;195:469–478. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0923-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson RE, Poulos CX. Sensitization to the behavioral effects of cocaine: Modification by Pavlovian conditioning. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1981;15:559–562. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(81)90208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirabayashi M, Alam MR. Enhancing effect of methamphetamine on ambulatory activity produced by repeated administration in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1981;15:925–932. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(81)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitzeman R, Wu J, Hom D, Loh H. Brain locations controlling the behavioral effects of chronic amphetamine intoxication. Psychopharmacology. 1980;72:93–101. doi: 10.1007/BF00433812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak Y. Modulation of cocaine- and methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization by inhibition of brain nitric oxide synthase. J Pharm Exp Ther. 1997;282:521–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak Y, Martin JL. Effect of riluzole and gabapentin on cocaine- and methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2000;151:226–233. doi: 10.1007/s002130000394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolta MB, Shreve P, De Souza V, Uretsky NJ. Time course of the development of the enhanced behavioral and biochemical responses to amphetamine after pretreatment with amphetamine. Neuropharmacology. 1985;24:823–829. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(85)90032-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyton M. Conditioned and sensitized responses to stimulant drugs in humans. Prog Neuro-Psychopharm Biol Psych. 2007;31:1601–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Ceng X, Huang M. Corticotrophin-releasing factor receptor type 1 mediates stress-induced relapse to opiate dependence in rats. Neuroreport. 2000a;11:2373–2378. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Zeng S, Liu D, Ceng X. Inhibition of the amygdale and hippocampal calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II attenuates the dependence and relapse to morphine differently in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2000b;291:191–195. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Huang M, Ma L, Li J. Different role of cholecystokinin (CCK)-A and CCK-B receptors in relapse to morphine dependence in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2001;120:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Koya E, Zhai H, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Role of ERK in Cocaine Addiction. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurski EJ, Beninger RJ. Environment-specific conditioning and sensitization with (+)-amphetamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1987;27:61–65. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(87)90477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Med-PC Activity Monitor Version 5. USA: Med-Associates, Vt.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Michel A, Tirelli E. Post-sensitization conditioned hyperlocomotion induced cocaine is augmented as a function of dose in C56BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2002;132:179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00400-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel A, Tambour S, Tirelli E. The magnitude and the extinction duration of the cocaine-induced conditioned locomotion-activated response are related to the number of cocaine injections paired with the testing context in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2003;145:113–123. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucha RF, Iversen SD. Reinforcing properties of morphine and naloxone revealed by conditioned placed preference: A procedural examination. Psychopharmacology. 1984;82:241–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00427782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller D, Stewart J. Cocaine-induced conditioned place preference: Reinstatement by priming injections of cocaine after extinction. Behav Brain Res. 2000;115:39–47. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00239-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller D, Perikaris D, Stewart J. Persistence and drug-induced reinstatement of a morphine-induced conditioned place preference. Behav Brain Res. 2002;136:389–397. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickens RW, Crowder WF. Effects of CS-US interval on conditioning of drug response, with assessment of speed of conditioning. Psychopharmacologia. 1967;11:88–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00401511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM. Intermittent versus continuous stimulation: Effect of time interval on the development of sensitization or tolerance. Life Sci. 1980;26:1275–1282. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(80)90085-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Becker JB. Enduring changes in brain and behavior produced by chronic amphetamine administration: A review and evaluation of animal models of amphetamine psychosis. Behav Brain Res. 1986;11:157–198. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(86)80193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory. Behav Res Rev. 1993;18:247–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. The incentive sensitization theory of addiction: some current issues. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363:3137–3146. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiff SR. Conditioned dopaminergic activity. Biol Psychiatry. 1982;17:135–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal DS, Kuczenski R. Behavioral pharmacology of amphetamine. In: Cho AK, Segal DS, editors. Amphetamine and Its Analogs. San Diego: Academic; 1994. pp. 115–150. [Google Scholar]

- Shaham Y, Hope BT. The role of neuroadaptations in relapse to drug seeking. Nature Neurosci. 2005;8:1437–1440. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirelli E, Tambour S, Michel A. Sensitized locomotion does not predict conditioned locomotion in cocaine-treated mice: Further evidence against the excitatory conditioning model of context-dependent sensitization. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;13:289–296. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(03)00037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirelli E, Michel A, Brabant C. Cocaine-conditioned activity persists for a longer time than cocaine-sensitized activity in mice: Implications for the theories using Pavlovian excitatory conditioning to explain the context-specificity of sensitization. Behav Brain Res. 2005;165:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilson HA, Rech RH. Conditioned drug effects and absence of tolerance to d-amphetamine induced motor activity. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1973;1:149–153. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Kalivas PW. Alterations in dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission in the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization: A critical review of preclinical studies. Psychopharmacology. 2000;151:99–120. doi: 10.1007/s002130000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]