Abstract

Providing information to patients regarding appropriate management of LBP is a crucial component of primary care and treatment of low back pain (LBP). Limited knowledge is available, however, about the information delivered by physicians to patients with low back pain. Hence, this study aimed at evaluating (1) the self-reported practices of French physicians concerning information about patients with acute LBP (2) the consistency of these practices with the COST B13 guidelines, and (3) the effects of the delivery of a leaflet summarizing the COST B13 recommendations on the management of patient information, using the following study design: 528 French physicians [319 general practitioners (GP) and 209 rheumatologists (RH)] were asked to provide demographic information, responses to a Fear Avoidance Beliefs questionnaire adapted for physicians and responses to a questionnaire investigating the consistency of their practice with the COST B13 guidelines. Half of the participants (163 GP and 105 RH) were randomized to receive a summary of the COST B13 guidelines concerning information delivery to patient with low back pain and half (156 GP and 104 RH) were not given this information. The mean age of physicians was 52.1 ± 7.6 years, 25.2% were females, 75% work in private practice, 63.1% reported to treat 10–50 patients with LBP per month and 18.2% <10 per month. The majority of the physicians (71.0%) reported personal LBP episode (7.1% with a duration superior to 3 months). Among the 18.4% (97) of the physicians that knew the COST B13 guidelines, 85.6% (83/97) reported that they totally or partially applied these recommendations in their practice. The average work (0–24) and physical activity (0–24) FABQ scores were 21.2 ± 8.4 and 10.1 ± 6.0, respectively. The consistency scores (11 questions scored 0 to 6, total score was standardized from 0 to 100) were significantly higher in the RH group (75.6 ± 11.6) than in GP group (67.2 ± 12.6; p < 0.001). The delivery of a summary of the COST B13 guidelines significantly improved the consistency score (p = 0.018). However, a multivariate analysis indicated that only GP consistency was improved by recommendations’ delivery.The results indicated that GP were less consistent with the European COST B13 guidelines on the information of patients with acute LBP than RH. Interestingly, delivery of a summary of these guidelines to GP improved their consistency score, but not that of the RH. This suggests that GP information campaign can modify the message that they deliver to LBP, and subsequently could change patient’s beliefs on LBP.

Keywords: Low back pain, Information, Guidelines, Beliefs

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a major health and economic problem among populations in western industrialized countries. International guidelines for the management of LBP generally agree that the condition should be principally managed in primary care [1, 2].

Providing information to patients regarding appropriate management of LBP is a crucial component of primary care and treatment of LBP. Studies show that the patient’s understanding of his or her pain significantly predicts treatment success [3] and increases patient’s satisfaction with their treatment [4]. However, a number of studies have shown discordance between the information provided by the physician and the expectations of patients with LBP [5–7]. Patient information is often based on physician’s assumptions of what patients may want or need to know; yet physician’s assumptions are often incomplete or incorrect [8, 9]. The lack of accurate physician knowledge can pose a critical barrier towards patient knowledge, despite the fact that patients express a need for a wide range of information on clinical, leisure activity, financial (social security for the treatment), psychological and social matters related to LBP [10]. Other barriers to adequate information include physician use of medical, legal and other jargon, lack of time, lack of communication skills and inaccurate attitudes and beliefs about LBP. As a result, many patients access information about LBP from a variety of other sources, which can be contradictory, leading to maladaptive beliefs about LBP and its consequences [7]. These inaccurate beliefs could then contribute to build a negative attitude toward pain including catastrophizing, coping and kinesiophobia which in turn increase the risk of a transition from acute to chronic pain.

Accurate information provision can avoid consequences of pain like fear avoidance, catastrophising and kinesiophobia and therefore reduce the risks of chronicity [11–13]. Patient information contributes to appropriate health care use as demonstrated for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and myorelaxant [4, 9, 14]. Most often, physicians provide information that focus on traditional biomedical issues such as knowledge of spinal anatomy, biomechanics, pathology, avoidance of activities that generate pain and advice on “good posture”, ergonomic advice, and back specific exercises. Information is also usually based on the physicians’ own beliefs about the causes of LBP, and may or may not be consistent with evidence or current guidelines for the clinical management of LBP.

At this time guidelines recommend information based on the biopsychosocial model that emphasizes the role of psychological and social factors in the development and maintenance of complaints [15]. Information based on the biopsychosocial model focuses on patient’s beliefs and attitudes, stresses the advantages of remaining active and avoiding best rest and provides reassurance that there is likely nothing seriously wrong. Recently, a systematic review has concluded that a biopsychosocial booklet is more efficient than a biomedical booklet for changing patient’s beliefs about physical activity, pain and consequences of LBP [16].

The primary objective of this study was to investigate whether the information delivered by physicians is consistent with the recent European COST B13 guidelines [2, 15, 17]. These recommendations were based on scientific data and developed within the framework of COST action B13 “Low back pain: guidelines for its management”, issued by the European Commission. According to these recommendations, the initial examination of LBP patients should serve as a basis for credible information to the patient regarding diagnosis, management and prognosis and may help in reassuring the patient. The guidelines recommend reassuring the patient by acknowledging the pain of the patient, being supportive and avoiding negative messages. They emphasize the importance of delivering [4] full information using words that the patient understands. The core message to the patient should be good prognosis, no need for X-rays, no underlying serious pathology, and stay active.

This study was designed to (1) assess the self-reported practices of French physicians concerning information they provide to patients with acute LBP (2) determine the consistency of these practices with the COST B13 guidelines, and (3) determine the effect of a leaflet summarizing the COST B13 guidelines on the consistency score.

Population and methods

Trial design

An observational, prospective and randomized study including 319 general practitioners (GP) and 209 rheumatologists (RH) was conducted.

Study questionnaires

After a review of the literature for identification of potentially useful variables and using a consensus process among the authors, a questionnaire was developed that included demographic and professional items, fears, avoidance attitudes and beliefs questionnaire (FABQ adapted for medical doctors) [18] and a scoring system evaluating the consistency of the physicians’ practices with the COST B13 guidelines. Part 1 of the physician self-administered questionnaire included demographic items (age and sex), professional items (medical specialty, years of practice experience, exclusively private or public/private practice, interest in LBP, special education in back pain, average number of LBP patients encounters per month) and personal history of LBP items (self-limitation of physical activities for LBP, LBP treatment administered, relatives LBP treatment). The relatives’ LBP treatment data were recorded by the physicians, only if they have treated their relatives for LBP. Part 2 asked about the information (frequency, type, method, impact for the patients) delivered to the patients. Part 3 assessed physician’s pain-related fears and avoidance attitudes using the fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ) [19], adapted for physicians’ use. The FABQ provides scores for two subscales: the FABQ Phys which measures fear-related beliefs about general physical activities (four items, range 0–24) and the FABQ Work which measures fear-related, beliefs about occupational activities (seven items, range 0–42). Each item of the FABQ is scored from 0, “do not agree at all”, to 6 “completely agree”. For both subscales, a lower score indicates lower fears and avoidance beliefs. The FABQ has been validated in French [20]. The original FABQ was developed to assess patients’ beliefs. In the current study, the wording of the items was modified to ask the physicians to rate the FABQ items with respect to beliefs that patients have expressed about their low back pain [18].

Part 4 of the questionnaire contained 12 items that assessed the consistency of respondent agreement with the COST B13 guidelines (Table 1). The contents of this section of the questionnaire results from a consensus of experts (members of the COSTB13 group) testifying of its content validity. The internal consistency of the questionnaire has also been tested (see statistical section). Each item was scored from 0, “do not agree at all”, to 6 “completely agree”. For items 6, 7 and 8 requiring a full disagreement to be consistent, the scoring system was inversed. Physicians who checked off “do not agree” received 6. The item “Manipulations performed by a health professional may worsen LBP” was withdrawn because it was judged ambiguous. The total raw score for this scale ranges between 0 and 66, but this was standardized in the current study to range from 0 to 100. A high score indicated high consistency with the COST B13 recommendations and a low score indicated a low consistency.

Table 1.

The consistency score

| Do not agree at all | Not sure | Completely agree | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. A thorough history taking and physical examination are enough to exclude serious spinal diseases | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 2. Currently, low back pain does not reflect a serious disease | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 3. A severe low back pain means that severe spine lesions are present | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 4. Most of the acute low back pain are self limiting and have not important consequence | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 5. X-rays are not essential for low back pain diagnosis and management | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 6. Spine imaging abnormalities have a pathological meaning | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 7. Bed rest is recommended for low back pain management | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 8. When it is prescribed, bed rest duration must be 2 days in minimum | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 9. To stay active is a good way to cure low back pain | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 10. Spine is made to move. To take up activity early helps low back pain patient to feel good | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 11. Prescribe medication to relief pain help patient to recover normal daily activities | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| 12. Spinal manipulation provided by professionals may worsen back pain | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Item 12 was deleted because of misunderstanding and decreasing internal consistency of questionnaire

To be consistent with the COSTB13 recommendations, MD have to completely agree with items 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11 and disagree with items 3, 6, 7, 8. The items 3, 6, 7, 8 were not consistent with COSTB13 recommendations

Population

GP participants were recruited through random sampling from a national database (CEGEDIM (CEntre de GEstion, de Documentation, d’Informatique et de Marketing), and RH participants were recruited from the register of the French Society of Rheumatology.

Data collection

All data were collected by self-questionnaires which were sent by mail to participants. Those agreeing to participate fulfilled the study questionnaires containing four parts and returned them to the monitoring center. Participants were then assigned by randomization to the intervention or control group. GPs and RH were randomized separately. According randomization RH or GP received 1 month later they return baseline questionnaire the information leaflet (intervention group) or not (control group). Then 1 month later they received again the part 4 of the questionnaire containing the 12 items assessing the consistency of respondent agreement with the COST B13 guidelines, fulfilled it and returned it to the monitoring center.

Intervention

One group received by mail a list of recommendations for patient information based on the COST B13 guidelines [2] and literature review [16]. Specifically, this information included the following: information on the mildness of LBP, on the uselessness of imaging, on the importance to stay active and on acute LBP management. Participants in the control conditions did not receive the leaflet. The information leaflet was developed by the members of the information group of the spine section of the French Society of Rheumatology. One month after sending the document, the participants were invited to again complete the consistency score sheet.

Data analysis

Physicians’ characteristics were computed for each group separately (group having received a summary of the COST B13 guidelines and the control group). The full analysis set was defined by physicians with data on their medical specialty and with at least a score of consistency at baseline.

Descriptive statistics included mean, standard deviation, range and median for quantitative parameters and were compared using non-parametric Wilcoxon test. Qualitative variables were described using percentage and were compared with a Fisher’s exact test. Changes of total score of consistency to COST B13 guidelines between score were compared using non-parametric Wilcoxon test. The relationship between score of FABQ and score information was studied using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Pearson’s r correlation can vary in magnitude from −1 to 1, with −1 indicating a perfect negative linear relation, 1 indicating a perfect positive linear relation and 0 indicating no linear relation between two variables. Correlation could be interpreted as small if r = 0.1; medium if r = 0.3 and large if r = 0.5 or upper.

To determine the internal consistency of the questionnaire assessing the agreement with the COSTB13 guidelines, its reliability was determined by using Cronbach’s alpha test. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranges from 0 to 1. The higher the coefficient, the more reliable the generated scale. It is widely accepted that a coefficient higher than 0.7 indicates a good reliability.

To study the effect of factors on the consistency score at baseline and on the change of this score, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out, taking into account the group, FABQ (fixed factor) and one factor at a time among physicians’ sex, medical specialization, years of practice, public/private practice, number of patients seen in consultations, personal history of LBP, LBP history of their relatives, training on LBP, number of paper read, knowledge of COST B13 guidelines, characteristics of the information delivered, individual/group information, expected impact of information was performed. A final model included the group, medical specialty, interaction group × specialty and all previous significant statistical factors. All the results obtained with ANOVA [(Statistical Analysis System (Proc Mix Procedure)] were expressed as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). As the study was exploratory, sample sizes was estimated at 500 participants. This number was estimated to allow a relevant multivariate analysis. The statistical analyses were conducted with the Statistical Analysis System 9.1.3. software for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Commission Nationale Informatique et Liberté. The study was conducted in compliance with the protocol of Good Clinical Practices and Declaration of Helsinki principles. In accordance with the French national law, physicians have given their written consent to participate after being informed about the study protocol.

Results

Flow of participants through trial

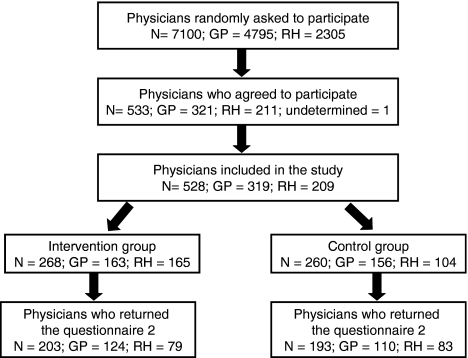

About 68,335 GP [mean age 49.0 year; 33.4% of women)] and 2,615 rheumatologists (mean age 51.0 year; 37.6% of women) are in activity in France in 2009 (National database from health ministry of France). A total of 7,100 physicians (4,795 GP and 2,305 RH) from the CEGEDIM (CEntre de GEstion, de Documentation, d’Informatique et de Marketing), and the French Society of Rheumatology registers were randomly selected and invited to participate in the study (Fig. 1). A total of 533 physicians [321 GP and 212 RH] agreed to participate and returned the first baseline questionnaire. Five of these did not indicate their medical specialty and/or did not respond to the COST B13 consistency questions. Only those participants who completed the baseline questionnaires (528; 209 RH and 319 GP) were subsequently randomized to receive the information brochure or not. 73.4% (234) of the GP and 77.5% (162) of the RH provided responses to the second COST B13 consistency questions, respectively. The number of physicians lost to follow-up did not differ significantly between the intervention and control group 65 (24.3%) and 67 (25.8%), respectively.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the study population randomization and follow-up

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of physicians was 52.1 ± 6.6 years and 25.2% were females. 61.6% have a medical activity since 20 years or more and 7.0% since <10 years. Characteristics of RH participating in the study (mean age 52.7 year, F 37.8%) were very close with the French National Data on medical population (mean age 51.0 year and F 37.6% on 2,615 RH in France). For GP, the percentage (mean age 51.2 year, F 16.9%) of men was higher than that of the French National Data on medical population (mean age 49.0 year and F 33.4% on 68,355 GP in France). The majority work in liberal and 54.7% in urban environment. The majority (66.3%) received between 10 and 50 patients with LBP per month, whereas 18.2% visited less than 10 patients with LBP per month and 14% more than 50 patients. Finally, 71% declared to have already suffered of LBP. The LBP duration was <4 weeks for 51.7%, between 4 and 12 weeks for 8.0% and more than 12 weeks for 7.5%. Recurrent episodes were reported by 36.5% of the physicians with LBP (Table 2). Baseline characteristics were similar in the intervention and control groups.

Table 2.

Demographic and professional characteristics, and personal history of back pain in physicians, physicians’ formation

| All physicians (N = 528) | Intervention group (N = 268) | Control group (N = 260) | p Value$ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age mean (SD) | 52.1 (7.64) | 52.5 (7.71) | 51.7 (7.56) | p = 0.16 |

| Gender (F) | 133 (25.2%) | 70 (26.1%) | 63 (24.2%) | p = 0.69 |

| Specialization (RH) | 209 (39.6%) | 105 (39.2%) | 104 (40.0%) | p = 0.86 |

| Years of practice | ||||

| <10 | 37 (7.0%) | 18 (6.7%) | 19 (7.3%) | p = 0.66 |

| 10–20 | 163 (30.9%) | 76 (28.4%) | 87 (33.5%) | |

| 21–30 | 224 (42.4%) | 116 (43.3%) | 108 (41.5%) | |

| >30 | 101 (19.1%) | 56 (20.9%) | 45 (17.4%) | |

| Environment of practice | ||||

| Rural | 289 (54.7%) | 155 (57.8%) | 134 (51.5%) | p = 0.14 |

| Urban | 93 (17.6%) | 50 (18.7%) | 43 (16.5%) | |

| Rural and urban | 144 (27.3%) | 62 (23.1%) | 82 (31.5%) | |

| Type of activity | ||||

| Hospital | 44 (8.3%) | 21 (7.8%) | 23 (8.8%) | p = 0.44 |

| Independent | 396 (75%) | 196 (73.1%) | 200 (76.9%) | |

| Hospital and independent | 84 (15.9%) | 48 (17.9%) | 36 (13.8%) | |

| Nb of LBP patients/month | ||||

| <10 | 96 (18.2%) | 46 (17.2%) | 50 (19.2%) | p = 0.48 |

| 10–50 | 350 (66.3%) | 174 (64.9%) | 176 (67.7%) | |

| >50 | 74 (14%) | 43 (16.0%) | 31 (11.9%) | |

| Personal history of LBP | ||||

| Yes | 375 (71%) | 181 (67.5%) | 194 (74.6%) | p = 0.10 |

| LBP duration | ||||

| <4 weeks | 194 (51.7%) | 87 (48.1%) | 107 (55.2%) | p = 0.18 |

| 4–12 weeks | 30 (8.0%) | 17 (9.4%) | 13 (6.7%) | p = 0.35 |

| >12 weeks | 28 (7.5%) | 13 (7.2%) | 15 (7.7%) | p > 0.99 |

| Personal LBP treatment | ||||

| Bed rest | 26 (6.9%) | 12 (6.6%) | 14 (7.2%) | p = 0.84 |

| Analgesic I | 151 (40%) | 68 (37.6%) | 83 (42.6%) | p = 0.34 |

| Analgesic II | 75 (20%) | 37 (20.4%) | 38 (19.6%) | p = 0.89 |

| Manipulation | 53 (14.1%) | 30 (16.6%) | 23 (11.9%) | p = 0.23 |

| Physical therapy | 70 (18.7%) | 31 (17.1%) | 39 (20.1%) | p = 0.50 |

| Back school | 5 (1.3%) | 2 (1.1%) | 3 (1.5%) | p > 0.99 |

| Relatives LBP treatment | ||||

| Bed rest | 55 (13.4%) | 33 (15.3%) | 22 (11.2%) | p = 0.25 |

| Analgesic I | 228 (55.5%) | 127 (59.1%) | 101 (51.5%) | p = 0.14 |

| Analgesic II | 172 (41.8%) | 79 (36.7%) | 93 (47.4%) | p = 0.03 |

| Manipulation | 97 (23.6%) | 51 (23.7%) | 46 (23.5%) | p > 0.99 |

| Physical therapy | 200 (48.7%) | 96 (44.7%) | 104 (53.1%) | p = 0.09 |

| Back school | 9 (2.2%) | 2 (0.9%) | 7 (3.6) | p = 0.09 |

$Non parametric tests (PROC NPAR1WAY option Wilcoxon for quantitative variables, PROC FREQ option Exact for qualitative variables)

LBP management

We have also investigated the treatment used by physicians to relieve their own LBP or the LBP of relatives. To treat their own LBP, 6.9% of the respondents reported using bed rest, 40.3% level I analgesics, 20% opoids, 14.1% osteopathy, 18.7% physiotherapy (including exercises) and finally 1.3% back school. Regarding the treatment of relatives, comparison between the RH and GP groups showed that GP referred more to osteopathy than RH (p < 0.01). 77.8% of the physicians declared to have already treated relatives for LBP. 50.4% of the physician’s relatives suffered of acute LBP (<4 weeks), 19% of subacute LBP, and 8% of chronic LBP and 26.5% of recurrent LBP. 13.4% of the physicians prescribed bed rest, 55.5% analgesic of level I, 41.8% opoids, 23.6% osteopathy, 48% physiotherapy (including exercises) and 2.2% back school (Table 2). Again, GP prescribed significantly more osteopathy than RH to treat their relatives (p = 0.006).

Training in LBP

About 56.3% of the participants reported that they had never participated in a training course on LBP care. 85.8% reported that they have read at least one paper on LBP in the past 12 months and 67.8% reported that they have read two or more papers on this subject. 43.0% have attended a congress on LBP. Significantly more GP than RH reported that they had never read a paper on LBP (7.5 vs. 4.3%; p < 0.001) and had never attended a congress on LBP (84.7 vs. 15.3%; p < 0.001). A large majority (81.3%) of the participants were unaware of the COSTB13 guidelines. Among physicians who reported at least some knowledge of the COSTB13, 40% declared that they apply these guidelines in their work. There was no difference between intervention and control groups concerning training in LBP care (Table 2).

FABQ

At baseline, FABQ Phys (scored between 0 and 24) was higher in GP (11.0 ± 5.9) than in RH (8.7 ± 6.1) (p < 0.001) participants. Similarly, the FABQ Work was higher in GP (22.2 ± 7.6) than in RH (19.6 ± 9.3) (p < 0.001) participants.

LBP Information delivery

The majority (72.3%) of the participants reported that they provided information about LBP often or systematically to their patients. Information was commonly delivered individually and was patient-focused. 43.4% of the participants said that they provided information to the patients and patient’s relatives. We have also investigated whether information content was in agreement with the COST B13 guidelines. We first verified the internal consistency of the questionnaire. Using 11 out of the 12 questions, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient had an acceptable value at 0.72. The coefficient was slightly lower (0.68) when the item “Manipulations performed by a health professional may worsen LBP” was included. This item was deemed ambiguous and was thus removed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Physicians’ education about LBP, COST B13 recommendations knowledge and use, and patients’ information

| All physicians (N = 528) | Intervention group (N = 268) | Control group (N = 260) | p value$ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formation on LBP | ||||

| 0 | 297 (56.3%) | 156 (58.2%) | 141 (54.2%) | p = 0.602 |

| 1 or 2 | 189 (35.8%) | 89 (33.8%) | 100 (38.5%) | |

| 2 to 5 | 30 (5.7%) | 17 (6.3%) | 13 (5%) | |

| >5 | 11 (2.1%) | 6 (2.2%) | 5 (1.9%) | |

| Not recorded | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Information sources | ||||

| Review | 453 (85.8%) | 232 (86.6%) | 221 (85%) | p = 0.620 |

| Pharmacological industry | 150 (28.4%) | 79 (29.5%) | 71 (27.3%) | p = 0.630 |

| Medical meeting | 289 (54.7%) | 140 (52.2%) | 149 (57.3%) | p = 0.256 |

| Web | 124 (23.5%) | 67 (25%) | 57 (21.9%) | p = 0.413 |

| Congress-symposium | 227 (43%) | 112 (41.8%) | 115 (44.2%) | p = 0.598 |

| Nb of papers read/year | ||||

| 0 | 33 (6.3%) | 12 (4.5%) | 21 (8.1%) | p = 0.181 |

| 1 or 2 | 133 (25.2%) | 71 (26.5%) | 62 (23.8%) | |

| 2 to 5 | 198 (37.5%) | 108 (40.3%) | 90 (34.6%) | |

| >5 | 160 (30.3%) | 76 (28.4%) | 84 (32.3%) | |

| Not recorded | 4 | 1 | 3 | |

| COST B13 knowledge | ||||

| Yes | 97 (18.4%) | 47 (17.5%) | 50 (19.2%) | p = 0.654 |

| No | 429 (81.3%) | 220 (82.1%) | 209 (80.4%) | |

| Not recorded | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| COST B13 use by those who know them | ||||

| Yes | 39 (7.4%) | 17 (6.3%) | 22 (8.5%) | p = 0.633 |

| No | 3 (0.6%) | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Partially | 45 (8.5%) | 23 (8.6%) | 22 (8.5%) | |

| Not recorded | 441 | 226 | 215 | |

| Patient information | ||||

| Never | 2 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | p = 0.710 |

| Occasionally | 20 (3.8%) | 7 (2.6%) | 13 (5%) | |

| Often | 116 (22%) | 61 (22.8%) | 55 (21.2%) | |

| Very often | 128 (24.2%) | 65 (24.3%) | 63 (24.2%) | |

| Systematically | 254 (48.1%) | 130 (48.5%) | 124 (47.7%) | |

| Not recorded | 8 | 4 | 4 | |

| Information modality | ||||

| Group | 3 (0.6%) | 1 (0.4%) | 2 (0.8%) | p = 0.619 |

| Individually | 522 (98.9%) | 265 (98.9%) | 257 (98.8%) | |

| Not recorded | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| Information target | ||||

| Patient only | 291 (55.1%) | 139 (51.9%) | 152 (58.5%) | p = 0.218 |

| Patient and relatives | 229 (43.4%) | 122 (45.5%) | 107 (41.2%) | |

| Not recorded | 8 | 7 | 1 | |

| Information impact on the patient | ||||

| Reluctance | 252 (47.7%) | 122 (45.5%) | 130 (50%) | p = 0.281 |

| Already known | 96 (18.2%) | 53 (19.8%) | 43 (16.5%) | |

| Not recorded | 180 | 93 | 87 | |

$Non parametric tests (PROC NPAR1WAY option Wilcoxon for quantitative variables, PROC FREQ option Exact for qualitative variables)

The main disagreements recorded were for item 1 (history taking and examination), items 5 and 6 (X-ray for diagnosis) and item 8 (bed rest duration; Table 4). The consistency score (range 0 to 100) was significantly higher in the RH than in GP (75.6 ± 11.5 vs. 67.2 ± 12.6; p < 0.001, not adjusted) participants. At baseline, the consistency score of physicians was significantly and inversely correlated with FABQ Phys (r = −027; p < 0.0001, n = 516) and FABQ Work (r = −0.20, p < 0.0001, n = 502), meaning that higher the reported fear-related beliefs, lower was the consistency of information provision with the COST B13 guidelines. Multivaried analysis showed that consistency score at baseline was explained by the specialty (p < 0.001), the systematic delivery of information (p = 0.0016) and the expected impact of the information on the patients (p = 0.011; Table 5).

Table 4.

Consistency score of all the physicians at baseline

| Items | Score at baseline (score 0 to 6)* | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A thorough history taking and physical examination are enough to exclude serious spinal diseases | 3.7 ± 1.64 |

| 2 | Currently, low back pain does not reflect a serious disease | 4.3 ± 1.64 |

| 3 | A severe low back pain does not mean that severe spine lesions are present** | 4.6 ± 1.43 |

| 4 | Most of the acute low back pain are self limiting and have not important consequence | 4.2 ± 1.58 |

| 5 | X-rays are not essential for low back pain diagnostic and management | 3.8 ± 1.94 |

| 6 | Spine imaging abnormalities have not a pathological meaning** | 3.7 ± 1.46 |

| 7 | Bed rest is not recommended for low back pain management** | 4.6 ± 1.59 |

| 8 | When it is prescribed, bed rest duration must be two days in maximum** | 3.3 ± 2.17 |

| 9 | To stay active is a good way to cure low back pain | 4.5 ± 1.26 |

| 10 | Spine is made to move. To take up activity early helps low back pain patient to feel good | 4.8 ± 1.17 |

| 11 | Prescribe medication to relief pain help patient to recover normal daily activities | 5.0 ± 0.97 |

* Scores range from 0, “do not agree at all”, to 6 “completely agree”. The higher the score, the better the consistency

** The items 3, 6, 7, 8 have been reversed to present results taking account the consistency COSTB13 recommendations of each item. Of course the calculation of scores were considered to be accurate

Table 5.

Adjusted mean value of score of consistency at baseline: factors statistically associated and selected by multivariate analysis

| Effect | Mean** | SEM | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialization | |||

| GP | 66.08 | 0.93 | <0.001 |

| RH | 72.20 | 1.29 | |

| Personal history of back pain | |||

| No | 67.80 | 1.28 | 0.0725 |

| Yes | 70.48 | 0.96 | |

| Information delivery | |||

| No systematically | 66.93 | 1.07 | 0.0016 |

| Systematically | 71.35 | 1.12 | |

| Expected effect of information on patients | |||

| Already known | 66.57 | 1.37 | 0.011 |

| Reluctance | 71.71 | 0.88 | |

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) model, taking into account the group, medical specialty, interaction group × specialty, FABQ (fixed factor) and statistical significant factors after an univariate analysis selected among physicians’ sex, medical specialization, years of practice, public/private practice, number of patients seen in consultations, personal history of LBP, LBP history of their relatives, training on LBP, number of paper read, knowledge of COSTB13 recommendations, characteristics of the information delivered, individual/group information, expected impact of information, and adresses of back pain information

** Standardized scores of consistency with COSTB13 recommendations: ranges 0 (non consistency) to 100 (consistency)

The delivery of a summary of the COST B13 guidelines on consistency score

The delivery of COST B13 guideline summary significantly improved the consistency score of physicians (intervention group + 3.8 points vs control group + 0.2 points; p = 0.001). The improvement was significantly more important in GP than in RH (GP + 4.92 points vs RH + 0.3 points; p = 0.016). The multivaried analysis showed that the factor explaining the changes of the consistency score after receiving the COST B13 guidelines summary was the medical specialty (p < 0.0106; Table 6).

Table 6.

Adjusted mean value of change score from baseline of consistency: factors statistically associated and selected by multivariate analysis

| Effect | Mean** | SEM | p value with adjustment on baseline value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | |||

| GP | 2.5358 | 0.9092 | 0.0106 |

| RH | −0.6514 | 1.0461 | |

| Sending of leaflet | |||

| No | −0.7271 | 0.9482 | 0.0060 |

| Yes | 2.6115 | 0.9916 | |

| Sending of leaflet by specialization | |||

| GP sending | 4.9233 | 1.1856 | 0.2342 |

| RH sending | 0.2998 | 1.4235 | |

| GP no sending | 0.1484 | 1.1972 | |

| RH no sending | −1.6027 | 1.3742 | |

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) model, taking into account the group, medical specialty, interaction group × specialty, FABQ (fixed factor) and statistical significant factors after an univariate analysis selected among physicians’ sex, medical specialization, years of practice, public/private practice, number of patients seen in consultations, personal history of LBP, LBP history of their relatives, training on LBP, number of paper read, knowledge of COSTB13 recommendations, characteristics of the information delivered, individual/group information, expected impact of information and addresses of back pain information

** Changes on the standardized scores of consistency with COSTB13 recommendations between first and second assessments

Discussion

The major aim of this study was to investigate the extent to which the information French physicians declare they deliver to patients with acute LBP is consistent with the recent COST B13 guidelines on LBP management. These guidelines emphasize (1) that X-ray is not needed for LBP diagnosis; (2) staying active is a good way to cure LBP; (3) bed rest is not a good treatment for LBP and should be avoided. Our results indicated that the surveyed physicians generally declared to deliver information consistent with the LBP guidelines. However, there were also indications that some physicians delivered messages that were not consistent with these guidelines. The primary inconsistency concerned the usefulness of X-ray (item 5 and 6) for LBP diagnosis and bed rest duration (item 8). This indicates that patients may in some instances get maladapted information about LBP diagnosis and best rest. Concerning the usefulness of X-ray, Balagué and Cedraschi [21] in a review of the recent literature emphasized the extent of the difficulties to adhere to guidelines and suggested a role not only for the anxiety of the patient but also for the anxiety of the therapist. This could be explained, at least in part, by the fear-related beliefs that some physicians have concerning LBP. The levels of fear-avoidance beliefs in our sample of physicians are higher than the usual cut-off [18]. The mean scores, 21.2 for FABQ Work and 10.1 for FABQ Phys, reveal some degree of fear-related beliefs. Furthermore, the consistency score was negatively correlated with the physician’s FABQ score, indicating that higher levels of fears beliefs are associated with lower consistency between the information the physicians provide for their patients and the COSTB13 guidelines. This suggests the possibility that those physicians who have fears themselves could negatively influence their patients’ beliefs and attitudes leading to catastrophizing and kinesiophobia [22, 23]. This is consistent with the Coudeyre’ study demonstrating that general practitioners with high rating on the FABQ Phys were less likely to follow recent recommendations for the management of LBP. For acute LBP, they were more likely to prescribe a long sick leave and bed rest during sick leave [18]. In short, the beliefs that physicians hold may determine how they communicate with patients, and this may ultimately impact on patient functioning (Table 6).

The consistency score was higher in RH than in GP indicating that RH were more likely than GP to provide information congruent with the guidelines to their LBP patients. One possible explanation could be that as much as 2/3 (66%) of the RH against only 1/3 (37%) of the GP have participated in at least one course on LBP management. Not surprisingly, RH also reported reading more papers and attending more congresses on LBP. Although quite low, a better awareness of the COSTB13 guidelines among the RH than among the GP (21.1 vs. 16.6%) may also account for these results. Taken together, these data indicate that RH were more sensitized to guidelines on LBP management than GP.

In our study, the prevalence of history of LBP was 71% and the prevalence of chronic low back pain was 7.1% which is in the range of the prevalence found in the general population [24, 25]. Physicians with a history of LBP trended towards a higher consistency score than those without LBP history. This difference (near of statistical significance p = 0.07) is observed with adjustment on FABQ, meaning that this factor may play an independent role in consistency. Therefore, we might speculate that physicians with history of LBP had a better confidence with the guidelines, possibly because they have experienced these guidelines themselves.

Finally, our study is the first report of a randomized control trial demonstrating that to provide a brochure that included recommendations to physicians may change the nature of the message delivery to patients with LBP. The reason that GP were better responders to this information probably was that GP had a lower baseline consistency score. Further, GP had a higher FABQ score than RH, indicating that GP hold more fear-avoidance beliefs than RH. This could explain that they were more sensitive to the information provided in framework of this study. However, even with an improved consistency score concordance with the guidelines relating to the bed rest duration remained poor for both groups. These results are consistent with previous published studies demonstrating that the provision of clinical practice guidelines is only partially successful in significantly improving physician concordance with the guideline-recommended treatment with diminished recommendations of prolonged bed rest and passive therapies and an increase in recommended aerobic exercise [26]. These findings also indicate that guidelines regarding the management of patients’ information have not been fully implemented into the patterns of practice of the physicians. Indeed, even after delivery of the brochure summarizing the guidelines, the consistency score was on average, only 71%. An appropriate next step is to devise more effective methods for implementing the guidelines. This could be accomplished, for example, via a media campaign targeting both physicians and patients, adapted to health-care system infrastructure and based on a consensus between evidence-based guidelines and patient’s expectations. Previous studies have shown that education programmes or mass media campaigns could modify GP practice behaviours for LBP [27, 28]. Evidence also indicates that promoting adherence to the LBP guidelines requires more than enhancing knowledge about evidence-based management of LBP [29]. Public education and an interdisciplinary consensus are important requirements for successful implementation of guidelines into daily practice.

This study has the usual limitations of studies based on self-reported medical practices. That is, there is no way to ensure that the findings reflect actual practice. Also, the findings were limited to two medical disciplines (RH and GP). We have no way to know who are those physicians who did not respond to our survey or why they did not accept to participate in the study. We cannot exclude that responders are those physicians who are the most interested in LBP and its management, including the use of guidelines. The findings therefore need to be replicated in samples including physicians from other disciplines (e.g. orthopaedic surgeons, rehabilitators) but also with physicians representing a large range of attitudes and behaviours regarding the management of LBP, and in different countries. In turn, the consistency questionnaire contained a limited number of items and may not have fully assessed all messages delivered by physicians during their consultation. Further, this questionnaire was not submitted to a full validation process. However, its content results from a consensus of experts (members of the COSTB13 group) which supports its content validity; besides, its internal consistency has been verified with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient higher than 0.7, thus indicating an acceptable reliability. Finally, the follow-up period was only 1 month. Even though previous studies have shown that information delivery with a leaflet has a short-term effect [16], it would be of interest to assess the consistency of the physicians’ responses to the recommendations in the longer term. Indeed, how the impact of the leaflet on the physicians’ practice regarding information delivery evolves over time remains an open question. Finally, this study investigated the declarative practices of the physicians and not what they really do. Further investigation comparing the patients and physicians declarations would be helpful to answer this question and to get further insight into the possible gap between the practitioners’ level of knowledge and actual practice habits.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings indicate that information delivered by physicians is partially, but not completely, consistent with the modern guidelines on the management of LBP. The findings also demonstrate that this guidelines-concordance can be improved by delivery of a short summary of these guidelines. Further investigation is needed to better determine the methods of application and the long-term effect of information on guideline-concordance in clinical practice of physicians. Further investigation is also required to evaluate the congruence between self-reported and actual practice habits, considering not only generic patients but also more specific problems where the strict implementation of the guidelines may raise issues in the patient-physician relationship, in the short- as well as in the longer-term. Information campaign triggering physicians’ beliefs could be helpful to improve guidelines’ implementation in general practice.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the French Society of Rheumatology and was conducted by members of the Spine section of the French Society of Rheumatology and of the Belgian Back Society.

Conflict of interest None.

Footnotes

On behalf of the Section Rachis of the French Society of Rheumatology.

References

- 1.Koes BW, Tulder MW, Ostelo R, Kim Burton A, Waddell G. Clinical guidelines for the management of low back pain in primary care: an international comparison. Spine. 2001;26:2504–2513. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200111150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, Breen A, del Real MT, Hutchinson A, et al. Chapter 3. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(Suppl 2):S169–S191. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-1071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deyo RA, Diehl AK. Psychosocial predictors of disability in patients with low back pain. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1557–1564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coudeyre E, Poiraudeau S, Revel M, Kahan A, Drape JL, Ravaud P. Beneficial effects of information leaflets before spinal steroid injection. Joint Bone Spine. 2002;69:597–603. doi: 10.1016/S1297-319X(02)00457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherkin D, Deyo RA, Berg AO, Bergman JJ, Lishner DM. Evaluation of a physician education intervention to improve primary care for low-back pain. I. Impact on physicians. Spine. 1991;16:1168–1172. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glenton C, Nilsen ES, Carlsen B. Lay perceptions of evidence-based information—a qualitative evaluation of a website for back pain sufferers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:34. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McIntosh A, Shaw CF. Barriers to patient information provision in primary care: patients’ and general practitioners’ experiences and expectations of information for low back pain. Health Expect. 2003;6:19–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00197.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ostelo RW, Stomp-van den Berg SG, Vlaeyen JW, Wolters PM, de Vet HC. Health care provider’s attitudes and beliefs towards chronic low back pain: the development of a questionnaire. Man Ther. 2003;8:214–222. doi: 10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jensen IB, Bodin L, Ljungqvist T, Gunnar Bergstrom K, Nygren A. Assessing the needs of patients in pain: a matter of opinion? Spine. 2000;25:2816–2823. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200011010-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gremeaux V, Coudeyre E, Givron P, Herisson C, Pelissier J, Poiraudeau S, et al. Qualitative evaluation of the expectations of low back pain patients with regard to information gained through semi-directed navigation on the Internet. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2007;50(348–55):339–347. doi: 10.1016/j.annrmp.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burton AK, Tillotson KM, Symonds TL, Burke C, Mathewson T. Occupational risk factors for the first-onset and subsequent course of low back trouble. A study of serving police officers. Spine. 1996;21:2612–2620. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199611150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ihlebaek C, Eriksen HR. Are the “myths” of low back pain alive in the general Norwegian population? Scand J Public Health. 2003;31:395–398. doi: 10.1080/14034940210165163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts L, Little P, Chapman J, Cantrell T, Pickering R, Langridge J. The back home trial: general practitioner-supported leaflets may change back pain behavior. Spine. 2002;27:1821–1828. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200209010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosemann T, Joos S, Koerner T, Heiderhoff M, Laux G, Szecsenyi J. Use of a patient information leaflet to influence patient decisions regarding mode of administration of NSAID medications in case of acute low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:1737–1741. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burton AK, Balague F, Cardon G, Eriksen HR, Henrotin Y, Lahad A, et al (2006) Chapter 2. European guidelines for prevention in low back pain: November 2004. Eur Spine J; 15 Suppl 2:S136–S168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Henrotin YE, Cedraschi C, Duplan B, Bazin T, Duquesnoy B. Information and low back pain management: a systematic review. Spine. 2006;31:E326–E334. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000217620.85893.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, Hildebrandt J, Klaber-Moffett J, Kovacs F, et al. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(Suppl 2):S192–S300. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-1072-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coudeyre E, Rannou F, Tubach F, Baron G, Coriat F, Brin S, et al. General practitioners’ fear-avoidance beliefs influence their management of patients with low back pain. Pain. 2006;124:330–337. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52:157–168. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaory K, Fayad F, Rannou F, Lefevre-Colau MM, Fermanian J, Revel M, et al. Validation of the French version of the fear avoidance belief questionnaire. Spine. 2004;29:908–913. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200404150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balague F, Cedraschi C. Radiological examination in low back pain patients: anxiety of the patient? Anxiety of the therapist? Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:508–513. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Boeren RG, Eek H. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995;62:363–372. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00279-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vlaeyen JW, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance and its consequences in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a state of the art. Pain. 2000;85:317–332. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00242-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersson GB. Epidemiological features of chronic low-back pain. Lancet. 1999;354(9178):581–585. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leclerc A, et al. Chronic back problems among persons 30 to 64 years old in France. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31(4):479–484. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000199939.53256.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bishop PB, Wing PC. Knowledge transfer in family physicians managing patients with acute low back pain: a prospective randomized control trial. Spine J. 2006;6:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buchbinder R, Jolley D, Wyatt M. Volvo award winner in clinical studies: effects of a media campaign on back pain beliefs and its potential influence on management of low back pain in general practice. Spine. 2001;26:2535–2542. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200112010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchbinder R, Jolley D. Population based intervention to change back pain beliefs: three year follow up population survey. BMJ. 2004;328:321. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7435.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chenot JF, Becker A, Leonhardt C, Keller S, Donner-Banzhoff N, Hildebrandt J, et al. Sex differences in presentation, course, and management of low back pain in primary care. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:578–584. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816ed948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]