Abstract

We have explored the use of a new model to study the transduction of chemosignals in the vomeronasal organ (VNO), for which the functional pathway for chemical communication is incompletely understood. Because putative vomeronasal receptors in mammalian and other vertebrate models belong to the superfamily of G-protein-coupled receptors, the objective of the present study was to define which G-protein subunits were present in the VNO of Sternotherus odoratus (stinkpot or musk turtle) in order to provide directionality for future functional studies of the downstream signaling cascades. The turtle vomeronasal epithelium (VNE) was found to contain the G-proteins Gβ and Gαi1–3 at the microvillar layer, the presumed site of signal tranduction in these neurons, as evidenced by immunocytochemical techniques. Gαo labeled the axon bundles in the VNE and the somata of the vomeronasal sensory neurons but not the microvillar layer. Densitometric analysis of Western blots indicated that the VNO from females contained greater concentrations of Gαi1–3 compared with males. Sexually immature (juvenile) turtles showed intense immunolabeling for all three subunits (Gβ, Gαi1–3, and Gαo) in the axon bundles and an absence of labeling in the microvillar layer. Another putative signaling component found in the microvilli of mammalian VNO, transient receptor potential channel, was also immunoreactive in S. odoratus in a gender-specific manner, as quantified by Western blot analysis. These data demonstrate the utility of Sternotherus for discerning the functional signal transduction machinery in the VNO and may suggest that gender and developmental differences in effector proteins or cellular signaling components may be used to activate sex-specific behaviors.

Indexing terms: G proteins, GTP-binding protein, vomeronasal organ, turtle, transient receptor potential, transient receptor potential channel

Sensory systems capture information from the environment and convey these signals to higher cortical centers in the brain, where the signals are processed to render an internal depiction of the external world (Dulac and Axel, 1995). In several classes of vertebrates, chemical sensory perception is mediated by sensory neurons at two anatomically distinct locations: the main olfactory epithelium (MOE) and the vomeronasal organ (VNO; Winan and Scalia, 1970; Broadwell, 1975; Scalia and Winan, 1975; Kevetter and Winan, 1981; Shepherd, 1988). Although they are of similar embryonic and neuronal origin (Cuschieri and Bannister, 1975), the two olfactory systems appear to diverge in function. The nature of the chemical cues encoded in each system is different (Halpern, 1987): The sensory neurons have unique biophysical properties (Liman and Corey, 1996); the molecular identities of putative transduction proteins that involve G-protein-coupled signaling cascades are notably different (Dulac and Axel, 1995; Berghard et al., 1996; Ryba and Tirindelli, 1997); and, finally, the sensory information transmitted from each olfactory system is directed to different brain regions (for review, see Keverne, 1999). Hence, the VNO emerges as a sensory organ that has a distinctive functional role in perception and has differentiated for the detection of specialized chemosignals. It is a partitioned region of the olfactory system that plays a strong role in the execution of species-typical behaviors, innate social or sexual behaviors, and the initiation of specific neuroendocrine changes (Halpern, 1987; Wysocki and Meredith, 1987). Jacobson (1811; modern translation, Trotier and Døving, 1998) anatomically described this previously unknown vertebrate sensory structure (Jacobson’s organ); however, nearly 2 centuries later, we do not completely understand the cellular events that take place to encode chemical information in the vertebrate VNO.

Despite the apparent differences in transduction machinery contained in the MOE versus the VNO, both systems express seven transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptors (Buck and Axel, 1991; Dulac and Axel, 1995). The subunit specificity and zonal expression of GTP-binding proteins in the VNO has provided insight into the putative downstream effectors. mRNAs encoding two of the seven G-protein α subunits expressed in the VNO, namely, Gαo and Gαi2, show high and regionalized expression in the mouse neuroepithelium (Berghard and Buck, 1996; Berghard et al., 1996). Both G proteins are enriched in the VNO microvilli, the presumed site of signal transduction in these neurons. In several studies using molecular or immunochemical probes (Shinohara et al., 1992; Luo et al., 1994; Dulac and Axel, 1995; Berghard and Buck, 1996; Berghard et al., 1996; Jia and Halpern, 1996), Gαi2 was found to be colocalized in the apical zone of the VNO with both adenylyl cyclase isoform II and the vomeronasal (VN) receptor type 1 class of VN receptors and with neural output from this region projecting to the rostral part of the accessory bulb. Gαo was localized to the basal zone of the VNO, with neural output from this region projecting to the caudal part of the accessory bulb. Molecular studies demonstrating differential expression of the two classes of VN receptors in conjunction with their colocalized G proteins with segregated projections to the higher centers in the accessory bulb have been instrumental in the formation of recent chemosignal coding theories (Bargmann, 1997; Belluscio et al., 1999; Keverne, 1999; Rodriguez et al., 1999).

With this backdrop of known molecular data supporting the involvement of G-protein-mediated signaling in the VNO, we sought to develop an animal model (Sternotherus odoratus; stinkpot or common musk turtle) that would provide an accessible VNO, a robust physiological preparation, and one for which behaviorally and physiologically relevant chemosignals (urine, skin extracts, and musk) could be harvested and applied to isolated neurons (Fadool et al., 2000a). These initial electrophysiological data demonstrate that VN neurons can be singly isolated and maintain voltage-activated, whole-cell currents. Furthermore, urine and musk elicit chemical-activated conductances in these isolated neurons (Fadool, submitted). The first step, however, in assessing signal-transduction cascades that are operational in S. odoratus (stinkpot or common musk turtle), was to characterize the G-protein subunit specificity in these turtles and any zonal expression of the proteins across the VNE. Herein, we report that GTP-binding proteins highly expressed in the mammalian VNO are localized to specific regions in the turtle VNO. Gβ and Gαi1–3 are most consistent with having a transductory role, because they are highly expressed in the microvillar layer compared with the VN somata, VN axon cell bundles, or nonneuronal cells. Interestingly, there appear to be both sexual dimorphism in GTP-binding protein expression as well as developmental changes in expression from the juvenile stage to the adult.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Solutions, reagents, and antibodies

Homogenization buffer (HB) contained (in mM): 320 sucrose, 10 Tris base, 50 KCl, and 1 ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, pH 7.8. Calcium-free turtle ringer solution contained (in mM): 116 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 15 glucose, 5 Na pyruvate, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. Turtle ringer solution contained (in mM): 116 NaCl, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 15 glucose, 5 Na pyruvate, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) contained (in mM): 136.9 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 10.1 Na2HPO4, and 1.8 KH2PO4, pH 7.4. All salts were purchased from either Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ) or Sigma Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO).

All antisera were polyclonal. Polyclonal rabbit antiserum to Gαo was purchased from NEN Life Science Products (Boston, MA) and was generated against the synthetic decapeptide, LDRIGAADYQ, representing amino acids 160–169 of mammalian Gαo (Goldsmith et al., 1988). Anti-Gαq/11, also purchased from NEN Life Science Products, was directed against the common C-terminal sequence of αq and α11. Anti-Gβ, purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), was raised in rabbits immunized with a synthetic decapeptide MSELDALRQE (amino acids 1–10 of bovine transducin β subunit) to be highly reactive with β1–β4. Anti-Gαolf was either purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (anti-Gαolf-sc) or provided as a generous gift from Dr. Albert Farbman (anti-Gαolf-af; North Western University, Evanston, IL) and was equivalent to Reed’s antiserum to peptide RR3 (CY coupled to KTAEDQGVDEKERREA, near the amino terminus of rat Golf; Jones and Reed, 1989). Anti-Gαi1–3 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Lake Placid, NY). Both affinity-purified antisera were raised against a peptide corresponding to an amino acid sequence within a highly divergent domain of Gαi-1, so that they would react with Gαi1–3. All G-protein subunit-specific antisera were used at a 1:100 dilution with the exception of Gαq/11, which was used at a 1:2,500 dilution, and Gαo, which was used at a 1:1,500 dilution. Anti-rTRP2 (a generous gift from Dr. Emily Liman; University of California, San Diego, CA) was generated against a glutathione-S-transferase fusion protein corresponding to the carboxyl terminus of the rat transient receptor potential channel (TRP2) gene (amino acids 814–885; Liman et al., 1999). Anti-olfactory marker protein, which recognizes a protein contained in mature olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) and vomeronasal sensory neurons (VSNs; Rogers et al., 1987), was a generous gift from Dr. Frank Margolis (University of Maryland Medical School).

Turtle capture and care

S. odoratus (stinkpot or common musk turtle) were captured at Auburn University (AU) Arboretum or at the Indian Pines Golf Course (Auburn, AL; average male plastron length (PL), 8.5 ± 0.4 cm; average male weight (W), 106.5 ± 3.1 g; average female PL, 8.5 ± 0.4 cm; average female W, 94.6 ± 5.1 g). Trachemys scripta (red-eared slider turtle) were similarly captured at AU Arboretum, at AU Aquaculture Research Station (Department of Fisheries and Allied Aquacultures), or at Indian Pines Golf Course (average male PL, 15.2 ± 0.3 cm; average male W, 678.0 ± 40.3 g; average female PL, 18.6 ± 0.3 cm; average female W, 1,150.5 ± 53.3 g). Pseudemys concinna (river cooter turtle) were a generous gift of Dr. Ray Henry at Auburn University (average male PL, 17.8 ± 0.3 cm; average male W, 994 ± 60.2 g; average female PL, 22.8 ± 0.63 cm; average female W, 1,331.3 ± 327.8 g). Adult turtles were captured using raw chicken-baited, 1–3 foot diameter hoop nets. All adult turtles were housed for approximately 1 month at AU Herpetology Facility, maintained on a 12 hour/12 hour light/dark cycle, and fed a standard diet of chicken or beef.

Turtle eggs (Keibert’s Turtle Farm, Hammond, LA) were incubated for approximately 69 days near 100% humidity. Temperature was monitored once per day with a glass thermometer, and eggs were held at 26°C to produce all male animals and at 33°C to produce all female animals (Bull and Vogt, 1979). Juvenile plastron length and turtle weights averaged 5.91 ± 0.56 cm and 58.15 ± 11.63 g, respectively. Juveniles were identified by carapace scoot markings (Cagle, 1939) and were housed in 10-gallon glass aquaria with light/dark cycles as described above. Juveniles were fed standard reptile pellet food (Tiger Shark Pets, Auburn, AL). Turtles were defined arbitrarily as adults at 4 years of age and as juveniles at 2 months of age.

Tissue collection

Vomeronasal organ (VNO) and main olfactory epithelium (MOE) were quickly dissected from turtles and rats (Sprague-Dawley; Simonsen, Gilroy, CA) using American Medical & Veterinary Association (AMVA) and National Institutes of Health-approved methods, as reviewed by the Animal Care and Use Committees of Florida State and Auburn University. Turtles were anesthetized on ice and then were given a lethal injection of methohexital sodium (0.13 mg/g body weight) followed by decapitation. Rats were killed by inhalation of CO2 followed by decapitation.

Cryosectioning

For cryosections, whole turtle VNOs and MOE were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 3 hours, followed by overnight infiltration with 10% sucrose in PBS, then 4 hours with 30% sucrose in PBS. VNOs and MOE were cut to a thickness of 9–12 µm on a Microm Laborgeräte GmgH microtome-cryostat (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Sections were transferred to 1% gelatin-coated glass slides (Sigma Chemical Company) and stored at −20°C until use. Section orientation was determined by cresyl violet staining (Sheehan and Hrapchak, 1973).

Immunocytochemistry

Prior to immunolabeling, slides were briefly fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 5 minutes to promote adhesion of the section to the gelatin slide. The fixative was removed by rinsing with two changes of PBS (Sambrook et. al, 1989) for 10 minutes each. Slides were incubated twice in PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) for 10 minutes each; then, nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation for 30 minutes in PBST containing 1–2% albumin fraction V (fatty acid free; Sigma Chemical Company; PBST-block) for cryosections. Slides and coverslips were incubated with primary antiserum diluted in PBST-block for 90 minutes at room temperature, washed with three changes of PBST, and then reincubated for 90 minutes at room temperature with a fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody at a 1:40 dilution (Boehringer-Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN) in PBST-block. Slides and coverslips were washed with two changes of PBST for 10 minutes, two changes of PBS for 10 minutes, rinsed in millipore water, and mounted in 60%/40% glycerol/PBS with 0.02% p-phenylene-diamine added to prevent photo-bleaching. Fluorescent photomicroscopy was performed at a magnification of ×40 using a CH-2 Olympus microscope (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with epifluorescence and a PM-10ADS Olympus automatic photomicrographic system. To appropriately compare control conditions (sera only) versus antisera-incubated conditions, all slides were treated identically with a standard 20-second shutter exposure. Histochemical staining microscopy was viewed with a Nikon Microphot FX (Tokyo, Japan) and photographed with a Minolta camera (FX-35WA) using Kodak Elite II 400 ASA film (Eastman-Kodak, Rochester, NH). Laser confocal microscopy was performed on a Bio-Rad MRC1000 microscope (Cambridge, MA) fitted with a Zeiss Axioskop using a ×40 plan neofluor objective. For all systems, 35-mm film was scanned with a Hewlett-Packard Photo-smart Scanner (model 106–816; Hewlett-Packard Corp, Corvallis, OR) or a Nikon LS2000. Digital files were imported into Photoshop (version 5.5; Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA) to facilitate multiple photomicrograph output on a Fuji Pictographic 3000 printer (Fuji Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Membrane preparation and biochemical analysis

Tissues were homogenized for 50 strokes using a Kontes tissue grinder (size 20) in HB solution on ice. The membrane proteins were then either solubilized in 0.5% Nonidet P-40 (NP40) or purified by centrifugation. For purification by centrifugation, homogenized tissue was centrifuged twice at approximately ×2,400 g (3800 RPM) for 30 minutes at 4°C in an Eppendorf centrifuge (model 5416; Eppendorf, Inc., Hamburg, Germany) to remove cellular debris. The supernatant was centrifuged in a Beckman ultracentrifuge (model L8-M; Beckman, Westbury, NY) at ×110,000 g (40,000 RPM) for 2.5 hours at 4°C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in HB solution and tip sonicated on ice three times for 20 seconds each with a Tekmar sonicator (setting 50; Tekmar, Cincinnati, OH). For solubilization with NP40, membranes were extracted by incubating with 0.5% NP40 on ice for 3–4 hours. Membranes were vortexed for 5 seconds every 30 minutes throughout the incubation. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 4°C in an Eppendorf model 5415 centrifuge (setting 14) for 15 minutes to remove cellular debris. The supernatant was harvested and the pellet discarded. After membrane purification by centrifugation or solubilization by NP40, protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay, and samples were stored at −80°C until use.

Membrane proteins were diluted in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel-loading buffer, pH 6.8 (Sambrook et al., 1989), and separated as a continuous front of 40 µg of protein using 10% acrylamide SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) except where otherwise noted. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose for Western blot analysis. Blots were blocked with 4% nonfat milk and incubated for 90 minutes at room temperature in several primary antisera using a Mini-Protean II Multi-screen Apparatus (Bio-Rad) across the continuous protein front. The blots were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody at a 1:3,000 dilution (Amersham-Pharmacia, Arlington Heights, IL) for 90 minutes at room temperature. Epichemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham-Pharmacia) was used to visualize labeled protein on Fuji RX film (Fisher). Exposure times were adjusted to account for differences in reactivity across antisera. Films were scanned with a Hewlett-Packard Photosmart Scanner (model 106–816) and analyzed with Quantiscan software (Biosoft, Cambridge, United Kingdom) as described previously (Fadool et al., 2000b).

Densitometric analysis

In experiments in which genders or developmental states were compared, membrane proteins from each sex or age were separated electrophoretically in the same PAGE apparatus, transferred to the same piece of nitrocellulose, and then exposed to the same x-ray film to standardize any variance in immunoreactivity or chemiluminescence exposure. Pixel units were determined for each labeled band for a given GTP-binding protein subunit and background subtracted within that same lane. Ratios of pixel density were then calculated as female:male or juvenile:adult, and then the average ratio for several experiments (n = 3–10 experiments) was computed. A Student’s t-test (using arc-sin transformation of percentage data) was performed to determine the significant difference in the mean expression of a subunit across two treatment groups, namely, between males and females or between adults and juveniles, as dictated by the experiment. Similar experimental design and data analysis were performed for gender and developmental expression of TRP2. In all cases, statistical significance was defined at the 95% confidence level.

RESULTS

Turtle VNO structure

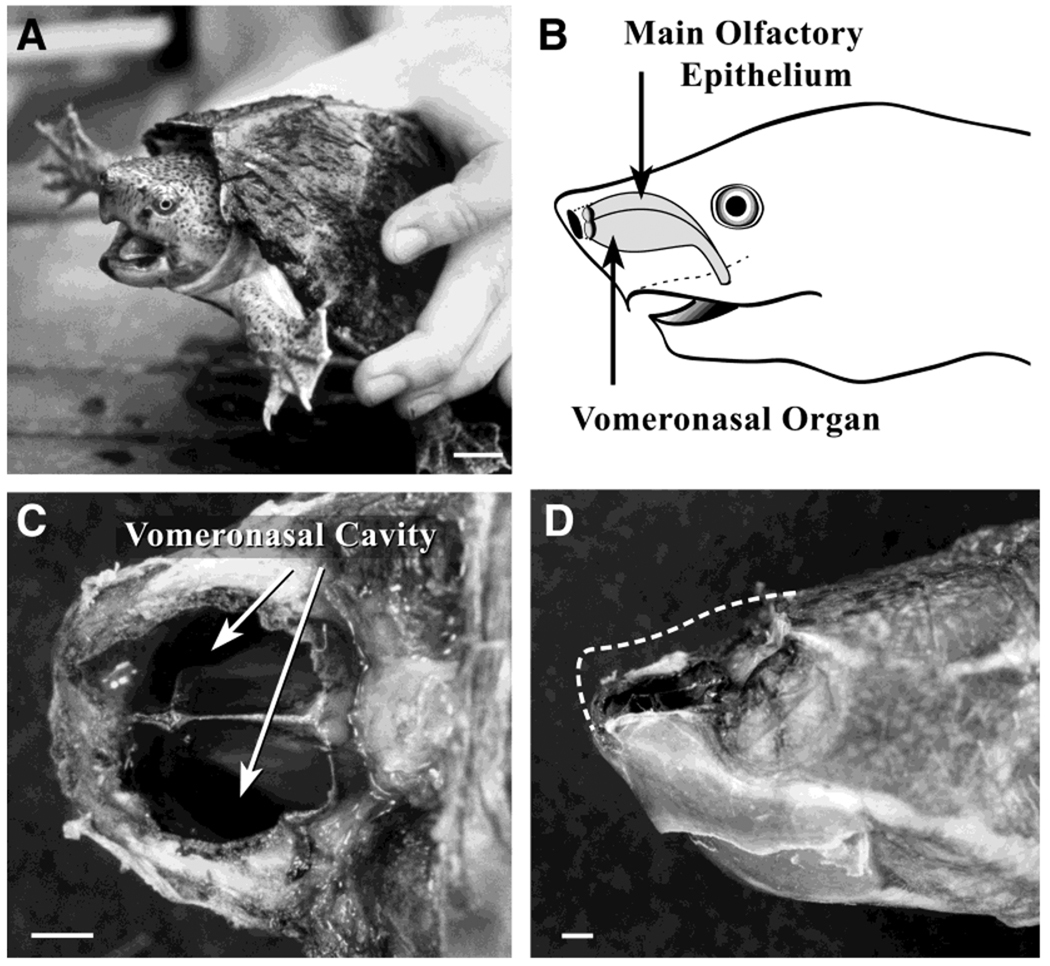

A total of 145 turtles across eight different species were found locally in our traps (see Materials and Methods) and were studied initially to select the most advantageous model for VN signal transduction. Animals were trapped from April to September over the 1998 and 1999 seasons to coincide with the peak reproductive cycle of the animal and included the following species: P. concinna, Trachemys scripta elegans, Graptemys flavimaculata, T.s. troostii, S. odoratus, S. carinatus, Chrysemys picta, and Chelydra serpentina. Although the Sternotherus species (musk or mud turtles; Fig. 1A) were highly sought as the primary focus of our study due to previously well-described reproductive life history, courtship behaviors, and behavioral responses to musk secretion, two of the above species (T.s. elegans and P. concinna) were also utilized for initial screens of GTP-binding proteins due to availability of animals and ease of VN access through the cranium. It was not a goal of the present study to compare VN structure with life history of a particular turtle species but, rather, to define GTP-binding protein expression in three turtles with similar life history, concentrating primarily on the Sternotherus species.

Fig. 1.

Selected research model and olfactory system anatomy. A: Handling the Sternotherus genus of turtle induces mild agitation, whereby the animal emits a species-specific chemosignal from its musk glands on the ventral surface of its plastron. Scale bar = 1.5 cm. B: Cartoon schematic denoting the dorsal location of the main olfactory epithelium (MOE) and the ventrally located vomeronasal organ (VNO), which are separated by a cartilaginous ridge. C: The compart-mentalization of the MOE and the VNO is more apparent from a superior view of the animal. In this photograph, the MOE has been removed, and the large vomeronasal cavity is visible. D: Lateral view of the Sternotherus odoratus shown in C. Dashed line indicates the outline of the MOE that has been removed. Scale bars = 1.0 mm.

All three species that we focused on were found to have a highly compartmentalized nasal chemosensory area, as diagramed in Figure 1B. The MOE was located dorsally, and the VNO was located ventrally; the two portions of the olfactory system were separated by a cartilaginous ridge. This ridge provided sequestration of the VSNs from the OSNs of the MOE, an arrangement that is not possible in some terrestrial turtle species. The VNO is comparatively larger than that found in mammals and is not encased in palatal elongations of intermaxillary bone; thus, accessibility with minimal manipulation was facilitated. In S. odoratus in particular, the proportion of the olfactory system dedicated to the VNO was greater than that of the MOE (Fig. 1C,D). Whether this arrangement correlates to a greater degree of dependence for function is not clear, but the proportionately larger VNO permitted suitable harvesting for biochemical preparations used in this study and suitable quantities for long recording periods for electrophysiological studies.

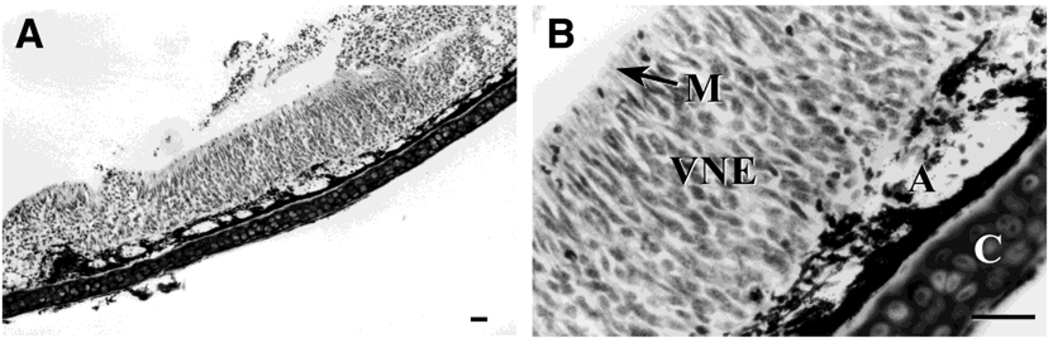

Ten animals (divided across the three species) were initially immunolabeled with anti-olfactory marker protein, which recognizes a protein contained in mature OSNs and VSNs (Rogers et al., 1987), as well as with anti-β tubulin III, which is used as a neural marker (data not shown). This labeling of neural structures as well as the general VN cytoarchitecture by cresyl violet (Fig. 2) allowed optimization of the procedures for cryoprotection and sectioning procedures, as defined in Materials and Methods. Although subtle variability in structure was noted across the three species, all contained four similar, prominent structures, as shown for S. odoratus in Figure 2B. The microvillar layer was readily identifiable, consistent with its first description at an electron microscopic level in box turtles (Graziadei and Tucker, 1970).

Fig. 2.

Structure of the turtle vomeronasal epithelium shown in photomicrographs of a 10-µm-thick coronal cryosection from the VNO of S. odoratus stained with cresyl violet. A: Low-magnification photomicrograph (original magnification, ×10) of the VNO section. B: Higher magnification photomicrograph (original magnification, ×40) of the same section. Four prominent structures are visible in these photomicrographs as labeled in B: cartilage (C), vomeronasal axon bundles (A), vomeronasal neuroepithelium (VNE), and the microvillar layer (M). Scale bars = 25 µm.

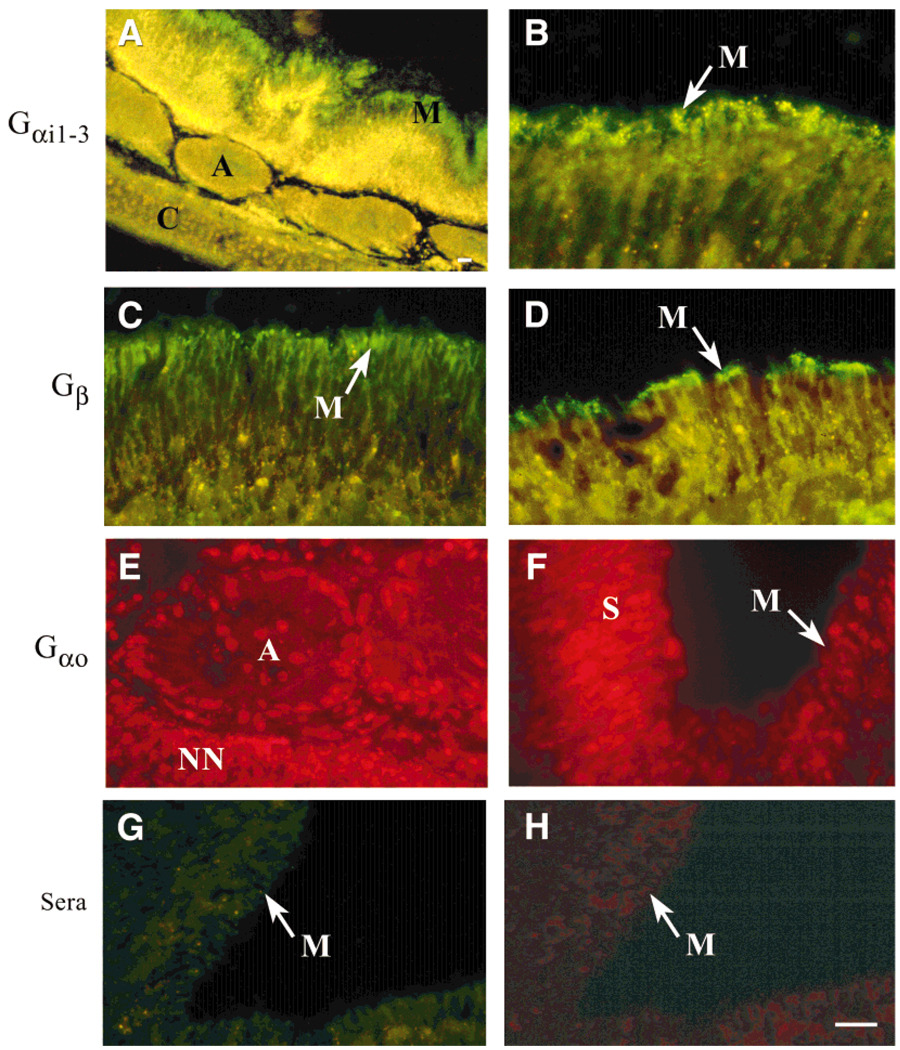

Localization of GTP-binding proteins within the VNE

Because the binding of a specialized chemosensory molecule to snake VNO membranes evokes a GTP-dependent process (Schulman et al., 1987), but GTP-binding proteins (G proteins) have not yet been characterized in the turtle VNO, we first performed immunocytochemical (ICC) experiments to demonstrate the presence and distribution of G proteins across the neuroepithelial layer of the turtle. Because a subset of G-protein subunits (αi2, αo, β1–4, αq, and γ8) have been shown to be highly or zonally expressed in the mammalian VNO (Ryba and Tirindelli, 1995; Berghard and Buck, 1996; Jia and Halpern, 1996; Wu et al., 1996; Yoshihara et al., 1997; Wekesa and Anholt, 1997), we screened a portion of this subset as well as the αolf subunit in 13 animals (divided across the three species and both sexes) using 10-µm-thick cryosectioned tissue. For S. odoratus and T.s. elegans, Figure 3 shows that Gαi1–3, Gαo, and Gβ proteins each were well expressed in the VNE. The previously described type of zonal expression patterns found in mammals were not observed for any of the subunits. However, there was differential labeling of cellular structures, in that anti-Gαi1–3 and anti-Gβ prominently labeled the microvillar layer (Fig. 3A–D), whereas anti-Gαo labeling was restricted to non-neuronal cell types surrounding the VN axon bundles and the somata of the VSNs (Fig. 3E,F). Based purely on this differential localization, it is conjectured that the αi1–3 and β subunits may function in transduction, whereas the αo subunit may have another, as yet undefined role in the VNO. Immunolabeling was not detected in sections incubated with anti-Gαolf, anti-Gαq/11, or preimmune rabbit sera or under conditions in which the primary antisera was omitted (Fig. 3G,H).

Fig. 3.

A–H: GTP-binding proteins localized in the turtle VNO shown in photomicrographs of 10-µm-thick coronal cryosections from the VNO of female adult T.s. elegans (red-eared slider; A,C,E) or female adult Sternotherus odoratus (common musk turtle; B,D,F–H). A–D: Sections were immunolabeled with Gαi antiserum (A,B) or with Gβ antiserum (C,D) and visualized with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Note the yellow-green autofluorescence inherent in the tissue and most apparent at lower magnification (A). This is distinct from the prominent labeling of the microvillar layer (M) for each of these G-protein sub-units at both lower (A) and higher (B–D) magnification. E,F: The same as shown in A–D but immunolabeled with Gαo antiserum and visualized with rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Note the immunolabeling of the nonneuronal (NN) cell types surrounding the vomeronasal axon bundles (A) in E and the somata of the vomeronasal sensory neurons (S) in F but an absence of labeling in the microvillar layer (shown in F). G,H: The same as above but incubated with nonimmune rabbit sera followed by FITC- or rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Scale bar = 75 µm.

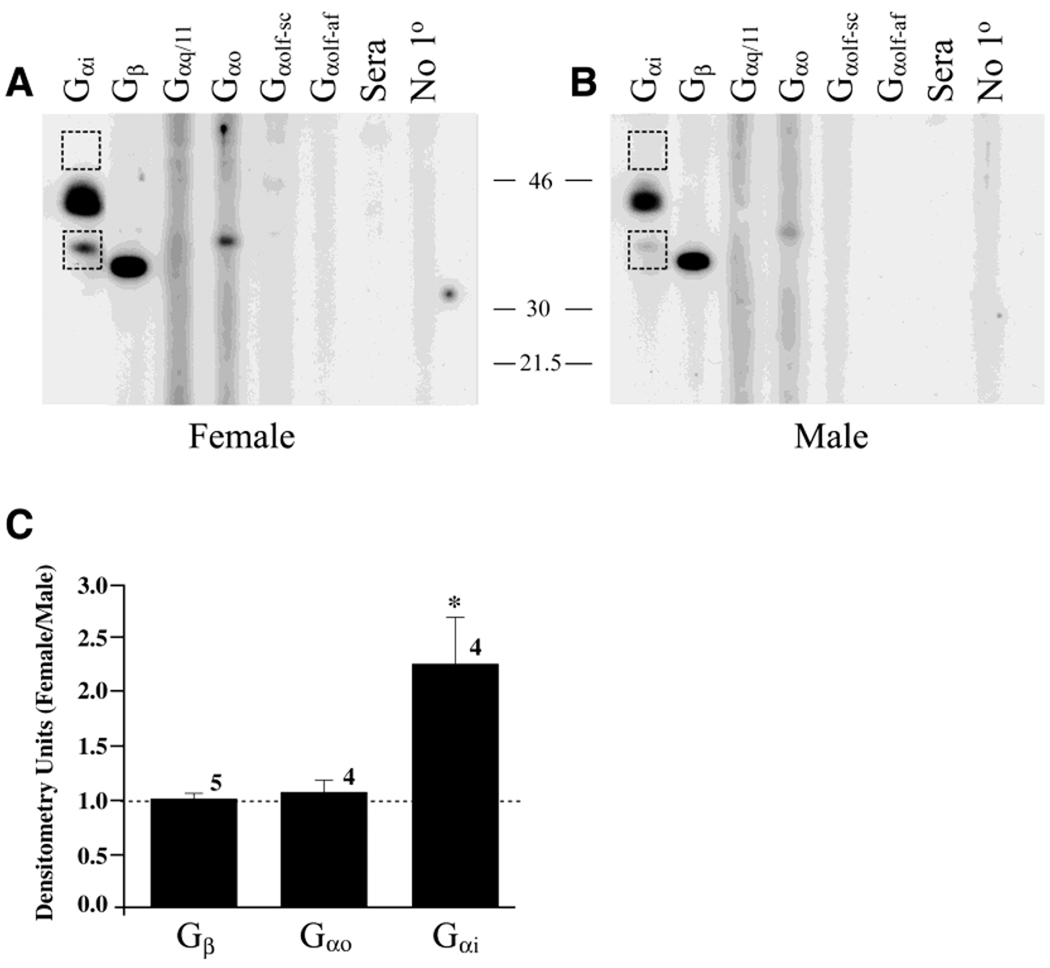

Sexual dimorphic expression of GTP-binding proteins

Although G proteins are highly evolutionarily conserved from human to paramecium (for review, see Neer, 1995), and we expected the polyclonal antisera to cross react with reptile proteins, it was important to confirm that these antisera recognized proteins of appropriate molecular weight for G proteins. SDS-PAGE separation of purified VNO membranes followed by Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of protein bands of expected molecular weight for Gαo, Gαi1–3, and Gβ, respectively (Fig. 4A,B), in both female and male turtles. The presence of these three subunits and the absence of Gαolf and Gαq/11 paralleled the ICC data described above; G-protein subunit composition in the VNO was identical whether using ICC or protein biochemical techniques as the metric. However, using the later combined with quantitative densitometry, it was found that membranes derived from female VN tissue contained approximately two-fold greater ECL signal for the Gαi1–3 subunit compared with that measured from male VN tissue (Fig. 4C; Student’s t test; arc-sin transformation; α = 0.05). Twenty-six similar pair-wise comparisons were made within species (S. odoratus, P. concinna, or T.s. elegans) and across female animals versus male animals. These data were analyzed similarly, as shown in Figure 4 for S. odoratus; all species demonstrated a significantly greater expression of the Gαi1–3 subunit in female VNO compared with that expressed in male VNO (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Sex-specific expression of GTP-binding proteins in the S. odoratus VNO. A,B: Purified membrane preparations of a female turtle VNO (A) and a male turtle VNO (B) separated as a homogeneous front by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Western blot analysis was performed for various G-protein subunits through use of a multiscreen apparatus to create slots to probe multiple antisera across a 40-µg continuous protein blot, as described in the text. C: Histogram representation of the ratio of female to male densitometry units calculated for appropriate molecular weight bands labeling the Gαo, Gαi1–3, and Gβ G-protein subunits, as described in the text. A ratio of 1.0 (no difference) is denoted by the dashed line. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (Student’s t-test; arc-sin transformation of percentage data, α = 0.05).

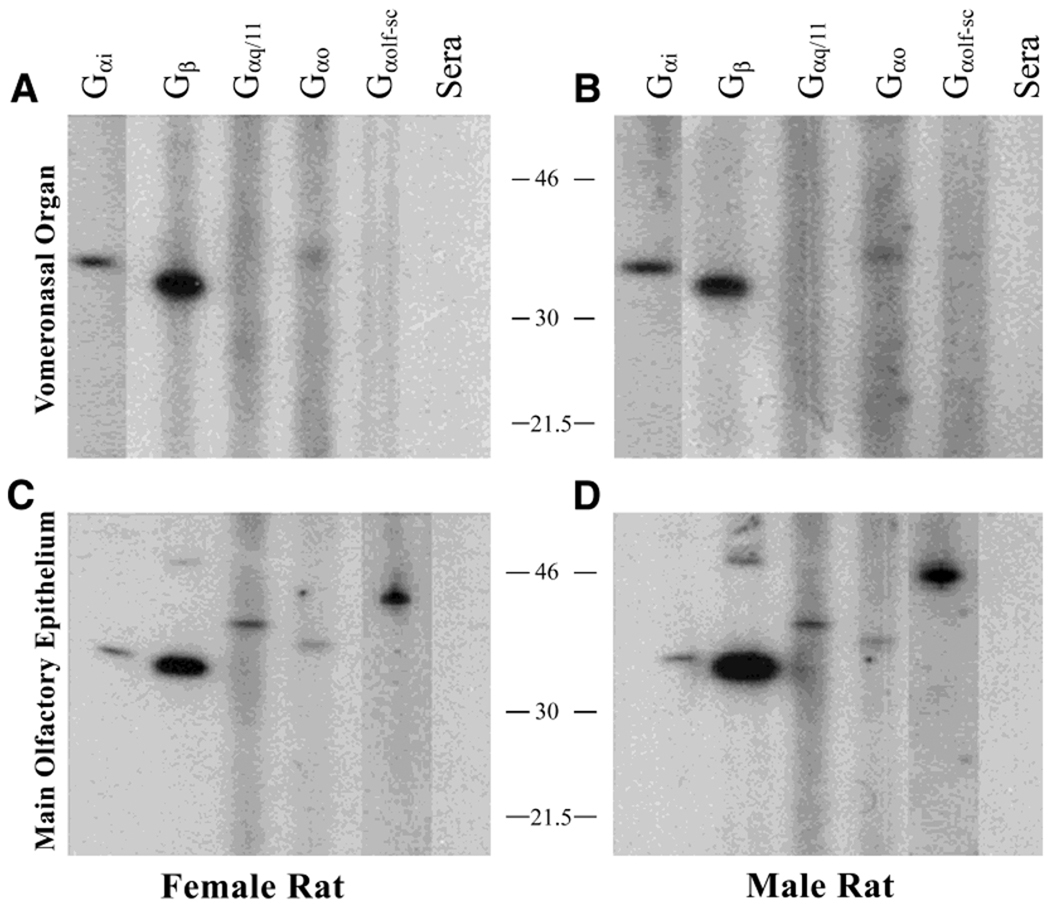

In both turtles and mammals, the second messenger 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) has been shown to evoke changes in VNO membrane conductance and is implicated in chemosignal transduction (Taniguchi et al., 1995; Inamura et al., 1997a,b). Because the effector protein phospholipase C (PLC) that converts phosphatidylinositol(4,5)-bisphosphate (PIP2) to IP3 is activated by both Gαo and Gαq/11 G proteins, we questioned the absence of detection of the later G protein in the turtle VNO. We tested the antigenicity of our battery of G-protein antisera in rat by SDSPAGE as a means to determine species cross reactivity. Using a purified whole-membrane preparation, as opposed to a ciliary or microvillar isolation, we were able to detect the same three G proteins, Gαo, Gαi1–3, and Gβ, in the rat VNO (Fig. 5A,B), like what was found in the turtle (Figs. 3, 4). For a comparative control, all five G-protein, subunit-specific antisera (including Gαolf and Gαq/11) detected G proteins of the appropriate size in the rat MOE (Fig. 5C,D). These data support the absence of both Gαolf and Gαq/11 subunits in the VNO system of rat and turtle.

Fig. 5.

The lack of sex-specific expression of GTP-binding proteins in the rat VNO is illustrated using the same experimental protocol that was used for Figure 4 but comparing male and female rat VNO and MOE. A,B: Note the expression of the same three subunits (Gαi1–3, Gβ, and Gαo) in the VNO of the rat that was found in the turtle VNO (see Fig. 4). C,D: Note the restricted expression of Gαq/11 and Gαolf-sc to the MOE (C,D) and the absence of these subunits in the VNO (A,B).

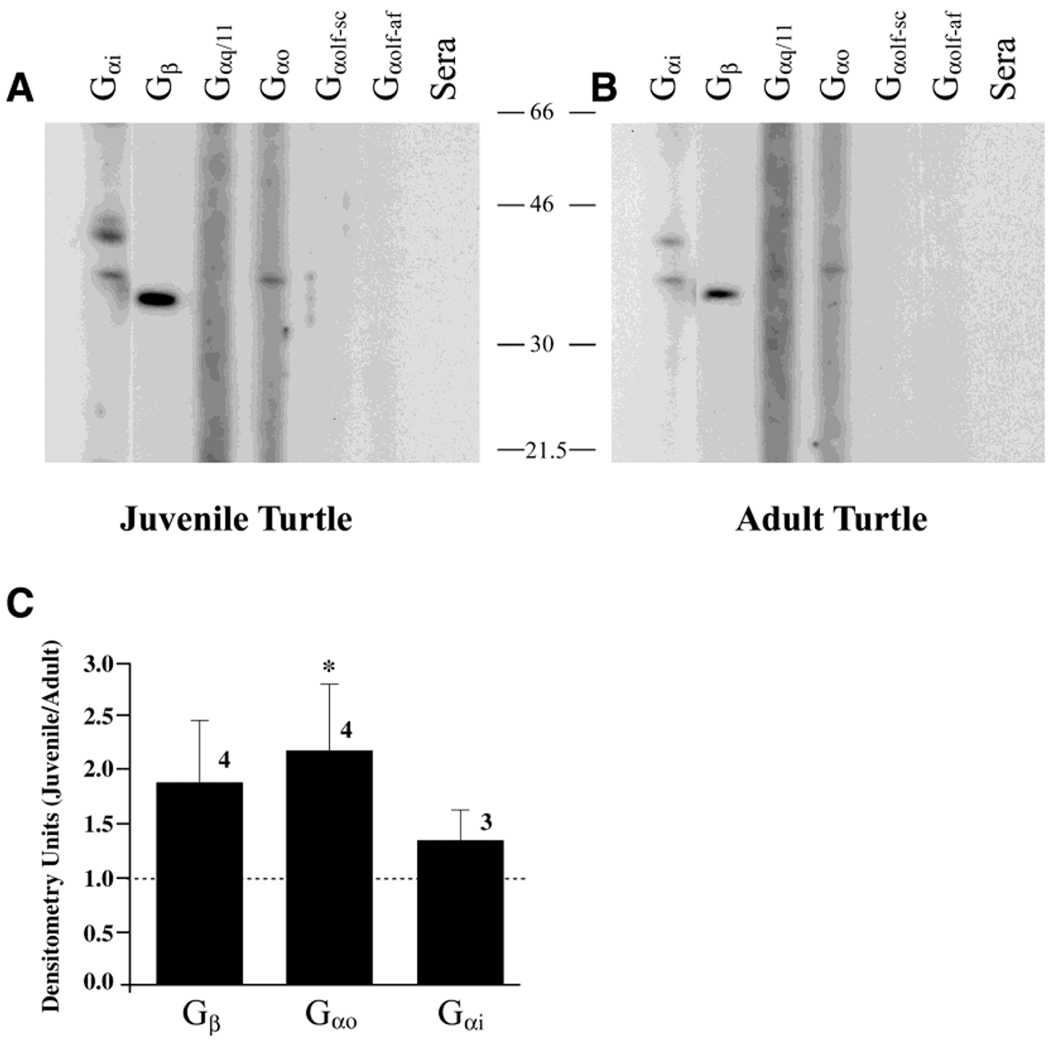

Developmental expression of GTP-binding proteins

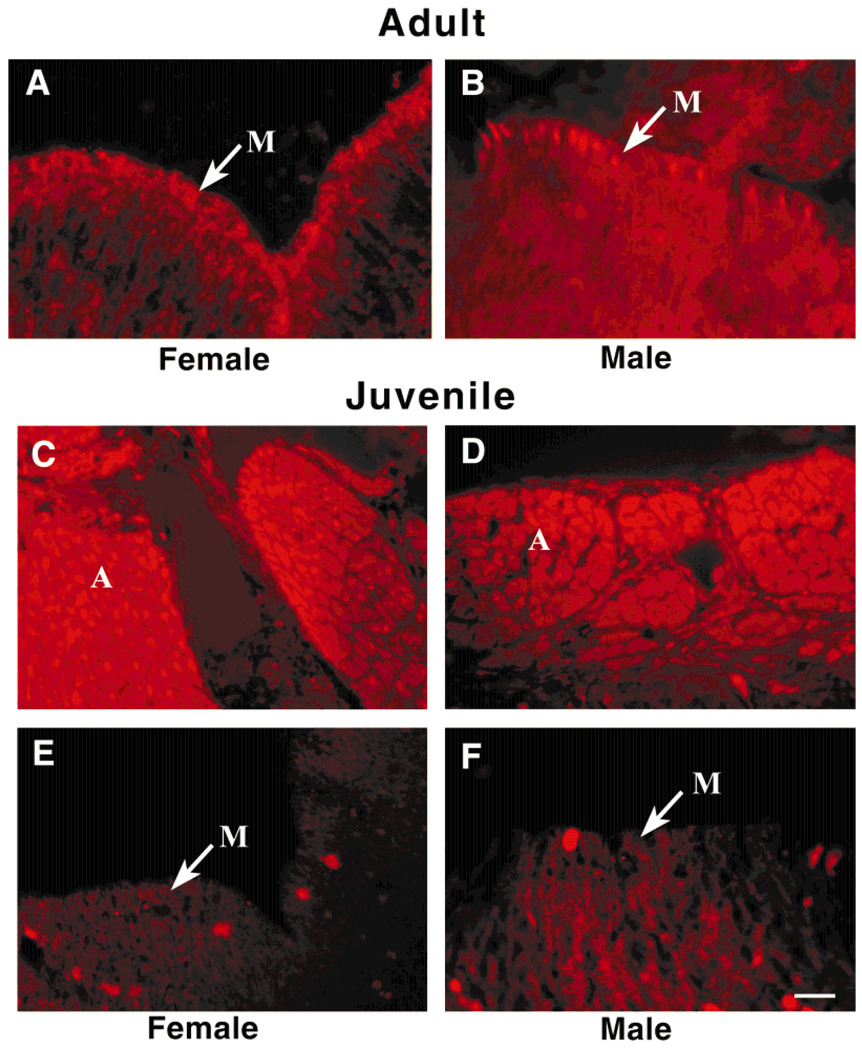

Detection of chemosignals specific to reproduction may not be imperative in juvenile animals that are not sexually mature. The underlying cellular machinery to transduce this information may be absent, reduced, or perhaps used for another function. To test this hypothesis, we raised hatchling turtles by incubating the eggs at differential temperatures to produce either all male or all female juvenile turtles. The distribution and level of expression of various G-protein subunits were then explored using immunochemistry and SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis, respectively (Figs. 6, 7). Labeling for anti-Gβ and anti-Gαi1–3, as shown previously in adult animals, was highly localized to the microvilli layer (Fig. 6A,B). In females, this staining was more evenly distributed across all VSNs (Fig. 6A), whereas, in males, the staining was more punctuate, with prominent staining in every other or every third VSN (Fig. 6B). Compared with adult animals, there was no differential staining between the sexes or between the various G-protein subunits in juveniles. Only the αi1–3, αo, and β subunits, as seen in adults, showed specific staining above background in the juvenile, but all three antisera labeled the VN axon nerve bundles (Fig. 6C,D) and showed an absence of staining in the VNE or microvillar layer (Fig. 6E,F). Quantifying the levels of expression of the various G-protein subunits in the juvenile VNO membranes by Western blot analysis showed that all three subunits (β, αo, and αi1–3) were elevated in juveniles (Fig. 7A,B), probably a reflection of the intense immunolabeling in the VN axon bundles, but only the Gαo subunit demonstrated a statistically significant increase (Fig. 7C; Student’s t test; arc-sin transformation; α = 0.05) over that found in adults.

Fig. 6.

The juvenile S. odoratus VNO contains a different G-protein distribution than that seen in sexually mature adult animals. A–F: Photomicrographs of 10-µm-thick coronal cyrosections comparing sex-specific Gβ-subunit immunolabeling in the adult (A,B) and juvenile (C–F) animal. A,B: Note the even distribution of signal in the microvillar layer of the adult female (A) compared with the punctate distribution in the adult male (B). Similar immunolabeling was found for the Gαi1–3 subunit in the adult (data not shown). C–F: In the juvenile animal, all subunits heavily label the VN axon cell bundles, as shown for the Gβ subunit in C and D. There is light reactivity in the VSN somata, and the microvillar layer is devoid of specific immunoreactivity (E,F). Scale bar = 37.5 µm.

Fig. 7.

Developmental expression of GTP-binding proteins in turtle VNO. A,B: SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis of purified membrane preparations of VNO from adult (A) and juvenile (B) animals, as shown in Figure 4. C: Histogram representation of the ratio of juvenile to adult densitometry units calculated as in Figure 4 for each sex and for the appropriate molecular weight bands labeling Gαo, Gαi1–3, and Gβ G-protein subunits. A ratio of 1.0 (no difference) is denoted by the dashed line. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (Student’s t-test; arc-sin transformation of percentage data, α = 0.05).

Sexual dimorphic and developmental expression of another signaling component

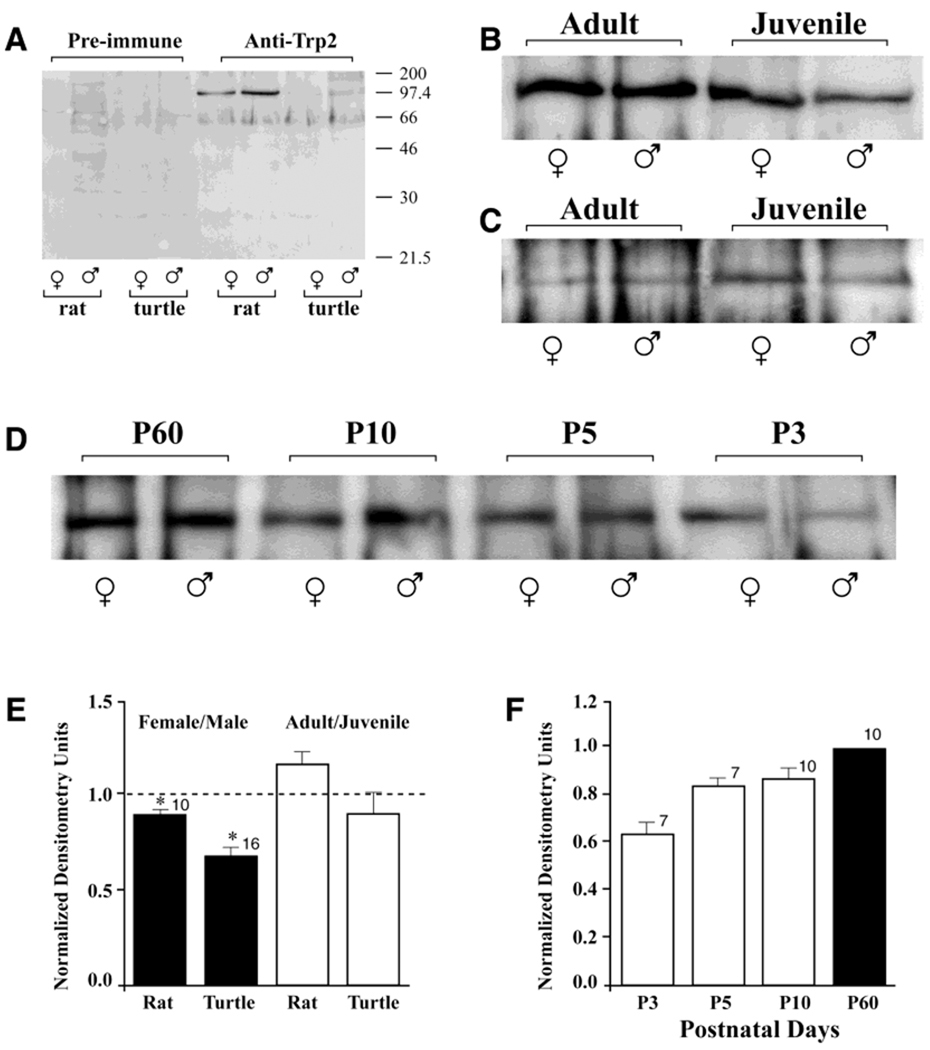

Recently, it has been shown that a member of the receptor channel TRP2 is highly expressed in the mammalian VNO microvilli (Liman et al., 1999). Although the ligand to gate this channel is still being investigated, there is some evidence that IP3 may gate its own receptor, which, in turn, interacts with TRP channels to cause a confirmation change and subsequent activation (Kiselyov et al., 1998). In rat, anti-TRP2 polyclonal antisera localized an appropriate size protein (90 kDa) by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 8A,B). Quantitative densitometry indicated that the signal for TRP2 protein was greater in the male VNO than in the female VNO (Fig. 8E; Student’s t-test; arc-sin transformation; α = 0.05). A band of similar electrophoretic mobility was observed for the S. odoratus VNO, also with gender-specific expression (Fig. 8A,C,E). A developmental change in expression was observed for the TRP2 signal in juvenile rat pups postnatal days 3–10 (P3–P10), which reached the adult level (P60) of TRP2 expression by P20 (Fig. 8D,F). In turtle, the TRP2 band was independent of reproductive maturity (adult age, 4 years; juvenile age, 2 months; Fig. 8C,E).

Fig. 8.

Developmental and sex-specific expression of transient receptor potential (TRP) family member, TRP2, in rat and S. odoratus VNO. A: Purified membrane preparations from adult rat or turtle VNO separated by SDS-PAGE. Twenty micrograms of protein were loaded in each lane. Nitrocellulose was labeled with the polyclonal antisera rTRP2 at a dilution of 1:400. B: The same as (A) comparing the adult rat (postnatal day 60; P60) with the juvenile rat (P10). C: The same as (A) comparing the adult turtle (4 years) with the juvenile turtle (2 months). D: The same as (B) comparing various rat postnatal stages from P3 to P60. E: Histogram representation of the ratio of female to male densitometry units calculated for the 90-kDa band visualized in rat and turtle, respectively, for the experimental conditions shown in (B,C). Units were calculated as described in text. A ratio of 1.0 (no difference) is denoted by the dashed line. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (Student’s t-test; arc-sin transformation of percentage data, α = 0.05). F: Histogram representation of postnatal TRP2 expressed in rat normalized to that expressed in the adult animal (solid bar).

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that the common musk turtle, S. odoratus (along with two other species), contains a specific complement of G-protein subunits in the VNO that are used to encode chemosensory information through a GTP-dependent mechanism. Data indicate that there is a division of function between that of the Gαi1–3 and Gβ subunits and that of the Gαo subunit based on localization of the former two subunits to the putative site of signal transduction. The fact that sexual dimorphism exists both in the level of Gαi1–3 subunit and the localization of Gαi1–3 and Gβ subunits within the VNE may be a reflection of differential detection and transduction of sex-specific molecules in these neurons.

The first evidence for a GTP-dependent mechanism involved in transduction of chemosignals in the VNO was discovered in another reptile, the snake (Luo et al., 1994). Across animal phyla, including mammalian, amphibian, and reptilian members, these same three subunits (Gαi1–3, Gβ, and Gαo) are expressed in the VNO (Luo et al., 1994; Berghard and Buck, 1996; Jia and Halpern, 1996; Wekesa and Anholt, 1997). The cellular localization and pattern of zonal expression vary, however, depending on species. Although segregation within the VNO for the αi and αo subunits exists in the turtle, in which Gαo is not coexpressed with Gαi1–3, there are not two distinct expression zones across the VNE for the two subunits, as has been reported in rodents and opossum (Berghard and Buck, 1996; Jia and Halpern, 1996). This lack of zonation across the VNE for Gαi1–3 and Gαo in the turtle is similar to what was reported most recently for goat, horse, screw, cat, and dog (Takigami et al., 2000). In these mammals, however, Gαo is completely lacking in either the VNO or the VN nerve layer of the accessory olfactory bulb. In the turtle, the G proteins Gαi1–3 and Gβ are highly localized to the microvillar layer, whereas Gαo is predominantly restricted to non-neuronal cells around the VN axon cell bundles and the somata of the VSNs. In contrast, in both snake and rodents, both Gαi and Gαo subunits are expressed in the processes/microvilli of the sensory portion of the VNO. Based on microvillar localization and sexual dimorphic expression, it appears that Gαi1–3 may be the most important transductory component in the turtle. Nonetheless, because G-protein subunit distribution is correlated with zonal neural projections to the accessory bulb (Jia and Halpern, 1996; Belluscio et al., 1999; Rodriguez et al., 1999), and selective activation of subunits has been linked with either the chemical nature of pheromonal components (Krieger et al., 1999) or the specific behaviors eliciting excitation of the VNO and accessory bulb (Kumar et al., 1999), segregation or subunit-specific expression of G proteins must be important and specific to VNO function for a particular species. A recent noteworthy finding is that fish do not contain a separate VNO (Anderson and Finger, 2000; Matsunami and Buck, 2000). Here, the ciliated neurons express Gαolf, and the microvillar neurons express Gαo. With respect to olfactory transduction in the MOE, as reviewed by Ache (1994), there is a limited set of transduction machinery available that may be drawn upon to encode chemosignal information. A similar analogy may be inferred for the VNO; different species may take on varied evolutionary approaches to transduce chemosensory information in the VNO.

Sexual dimorphism in the nervous system has been observed in the volume and size of structures, the number of synapses, the number of cells, and the length of neural processes. Explicit sex differences have been reported in the rat VNO as well as in the accessory bulb, where the overall volume, neuroepithelial volume, and number of bipolar cells are all larger in males (Segovia and Guillamón, 1996; Guillamón and Segovia, 1997). In salamanders, nose tapping, a method of VNO stimulation used repeatedly by males during courtship, is hypothesized to contribute to the greater VNO volume observed in males compared with females (Dawley, 1992). Sexual dimorphism may also exist at the molecular level to trigger electrical stimulation of restricted population of neurons to generate sex-specific behavioral responses to certain chemosignals (Herrada and Dulac, 1997). In the turtle, we observed dimorphism, in both concentration and distribution of G proteins. This was exemplified in the higher level of Gαi1–3 in adult females compared with adult males and the more even distribution of Gαi1–3 and Gβ across the microvillar surface in females compared with males. These differences and subsequent activation of downstream effector proteins may trigger gender-specific behavioral responses during courtship. This hypothesis is consistent with our finding of G-protein redistribution from the axon cell bundles to the microvillar layer during maturation and suggests a change in function for these proteins in the adult. G-protein concentrations in axon terminals have been hypothesized to play a role in axon guidance (Berghard and Buck, 1996; Tanaka et al., 1999), a function that would be beneficial during such development. Such sexual dimorphism and developmental dependency has been reported in other molecular studies of olfaction. For example, Gαi2 has been reported to increase in the rat accessory bulb at the onset of puberty (Shinohara et al., 1992). The VR2 class of putative pheromone receptors closely associated with Gαi2 proteins is expressed in a large and centrally located region of the VNE in female rats, whereas, in male rats, the same class of receptors is restricted to the most apical side of the VNE, closely apposed to the VNO lumen (Herrada and Dulac, 1997).

A general working hypothesis for the degree and extent of involvement of second messengers in VNO signal transduction is unclear. In the Reeve’s turtle, in which the VNO is not highly sequestered from the MOE, neurons terminating in microvillar structures have been found to evoke inward currents in response to patch-pipette dialysis of two different second messengers, cyclic AMP (cAMP) and IP3 (Taniguchi et al., 1995, 1996). In this species, neither a chemoattractant nor a substance that activates either the IP3 or the cAMP cascade has been identified, so that the physiological role for these second messengers in turtle is unclear at this time. An IP3-evoked conductance and an absence of a cAMP-evoked conductance has recently been reported in snake (Taniguchi et al., 2000). The recent finding of TRP2 localization to the microvilli in the rat VNO (Liman et al., 1999) may also suggest the involvement of IP3, because this recent family of channels is thought to be activated by release of calcium stores (Kiselyov et al., 1998). We show that this transduction element is present in the musk turtle and that the apparent molecular weight for TRP2 in the turtle is consistent with that found in the rat. However, the protein does not show a change in expression linked with sexual maturity of the animal. Because the level of TRP2 rises quite early in rat postnatal development (Liman et al., 1999), it cannot be ruled out that TRP2 expression increases in the turtle prior to 2 months. Finally, in formulating a working hypothesis for VNO transduction, it is important to remember that most secretions or excretions that are used for communication consist of a large number of compounds. This complicates the straightforwardness of cell signaling/transduction cascades and could infer that the two partitions of the olfactory system may not work independently but interact to identify an odor mixture or “signature” (Johnston, 1998).

We have explored the use of a beneficial model for the study of vertebrate signal transduction of chemical cues encoded through the VNO. The musk turtle has dimorphic, developmental, and cell-specific localization of G proteins indicative of a GTP-dependent transduction mechanism in the VNO. Now that the expression of a critical component of this cell signaling (G proteins) has been demonstrated, we are well poised to initiate an investigation of the chemosignal-activated conductances in these neurons. Having the capacity to explore developmental and seasonal fluctuations in transduction mechanisms as well as the availability of a variety of chemosignals (anterior vs. posterior musk gland secretions; Ehrenfeld and Ehrenfeld, 1973; Eisner et al., 1977; urine, skin extracts, aquaria water samples, and general food odorants) should help to expand our working knowledge of how animals encode reproductive chemical information into electrical signals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R15DC03318 to D.A.F. and an Undergraduate Howard Hughes Life Scholars Award to F.A.M. We are indebted to the spirit, dedication, and expertise of Dr. Mary Mendonça, who first introduced our laboratory to this research model. We are thankful to Ms. Jennifer Shelby and Mr. Brian Hauge for their provided expertise in turtle maintenance and turtle hatchlings. We thank Drs. Albert Farbman, Frank Margolis, and Emily Liman for generous donation of antibodies. We are thankful to our colleagues Drs. James Fadool, Paul Trombley, and Michael Meredith for critically reviewing our article prior to submission. We thank Drs. Mary Mendonça, Craig Guyer, and Steve Kempf for access to technical equipment to perform our experiments. We thank the Auburn Fisheries Department and Dr. Ray Henry for donation of animals. We are indebted to Mr. Charles Badland for his photographic and artistic services.

LITERATURE CITED

- Ache BW. Towards a common strategy for transducing olfactory information. Semin Cell Biol. 1994;5:55–63. doi: 10.1006/scel.1994.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KT, Finger TE. Immunohistochemical localization of Go in a subset of goldfish and catfish olfactory receptor neurons and bulbar glomeruli [abstract] Chem Senses. 2000;25:669. [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CL. Olfactory receptors, vomeronasal receptors, and the organization of olfactory information. Cell. 1997;90:585–587. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80518-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluscio L, Koentges G, Axel R, Dulac C. A map of pheromone receptor activation in the mammalian brain. Cell. 1999;97:209–220. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80731-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghard A, Buck LB. Sensory transduction in vomeronasal neurons: evidence for Gαo, Gαi2, and adenylyl cyclase ll as major components of a pheromone signaling cascade. J Neurosci. 1996;16:909–918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-00909.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghard A, Buck LB, Liman ER. Evidence for distinct signaling mechanisms in two mammalian olfactory sense organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2365–2369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.6.2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadwell RD. Olfactory relationships of the telencephalon and diencephalon in the rabbit. An autoradiographic study of the efferent connections of the main and accessory olfactory bulbs. J Comp Neurol. 1975;163:329–346. doi: 10.1002/cne.901630306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck L, Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: a molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell. 1991;65:175–187. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull JJ, Vogt RC. Temperature-dependent sex determination in turtles. Science. 1979;206:1186–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.505003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagle FR. A system of markings turtles for future identification. Copeia. 1939;3:155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cuschieri A, Bannister LH. The development of the olfactory mucosa in the mouse: light microscopy. J Anat. 1975;119:277–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawley EM. Sexual dimorphism in a chemosensory system: the role of the vomeronasal organ in salamander reproductive behavior. Copeia. 1992;1:113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dulac C, Axel R. A novel family of genes encoding putative pheromone receptors in mammals. Cell. 1995;83:195–206. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenfeld JG, Ehrenfeld DW. Externally secreting glands of fresh-water and sea turtles. Copeia. 1973;2:305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Eisner T, Conner WE, Hicks K, Dodge KR, Rosenberg HI, Jones TH, Cohen M, Meinwald J. Stink of stinkpot turtles identified: w-Phenylalkanoic acids. Science. 1977;196:1347–1349. doi: 10.1126/science.196.4296.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadool DA, Person DJ, Murphy FA. Sexual dimorphism and developmental expression of signal transduction machinery in the vomeronasal organ [abstract] Chem Senses. 2000a;25:677. doi: 10.1002/cne.1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadool DA, Tucker T, Phillips JJ, Simmen J. Brain insulin receptor causes activity-dependent current suppression in the olfactory bulb through multiple phosphorylation of Kv1.3. J Neurobiol. 2000b;83:2332–2348. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.4.2332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith P, Backlund PS, Rossiter K, Carter A, Milligan G, Unson CG, Spiegel A. Purification of heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins from brain: identification of a novel form of Go. Biochem J. 1988;27:7085–7090. doi: 10.1021/bi00418a062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziadei PPC, Tucker D. Vomeronasal receptors in turtle. Z Zellforsch. 1970;105:498–514. doi: 10.1007/BF00335424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillamón A, Segovia S. Sex differences in the vomeronasal system. Brain Res Bull. 1997;44:377–382. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(97)00217-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern M. The organization and function of the vomeronasal system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1987;10:325–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.10.030187.001545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrada G, Dulac C. A novel family of putative pheromone receptors in mammals with a topographically organized and sexually dimorphic distribution. Cell. 1997;90:763–773. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamura K, Kashiwayanagi M, Kurihara K. Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate induces responses in receptor neurons in rat vomeronasal sensory slices. Chem Senses. 1997a;22:93–103. doi: 10.1093/chemse/22.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamura K, Kashiwayanagi M, Kurihara K. Blockage of urinary responses by inhibitors for IP3-mediated pathway in rat vomeronasal sensory neurons. Neurosci Lett. 1997b;233:129–132. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00655-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson L. Description anatomique d’un organe observe dans les mammifieres. Ann Mus Hist Nat. 1811;18:412–424. [Google Scholar]

- Jia C, Halpern M. Subclasses of vomeronasal receptor neurons: differential expression of G proteins (Gi2 and Go) and segregated projections to the accessory olfactory bulb. Brain Res. 1996;719:117–128. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RE. Pheromones, the vomeronasal system, and communication. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;855:333–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DT, Reed RR. Golf: an olfactory neuron specific G-protein involved in odorant signal transduction. Science. 244:790–795. doi: 10.1126/science.2499043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keverne EB. The vomeronasal organ. Science. 1999;286:716–720. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5440.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevetter GA, Winan SS. Connections of the croticomedial amygdala in the golden hamster. Efferents of the vomeronasal amygdala. J Comp Neurol. 1981;197:81–98. doi: 10.1002/cne.901970107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselyov K, Xu X, Mozhayeva G, Kuo T, Pessah I, Mignery G, Zhu X, Birnbaumer L, Muallem S. Functional interaction between insp3 receptors and store-operated htrp3 channels. Nature. 1998;396:478–482. doi: 10.1038/24890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger J, Schmitt A, Lobel D, Gudermann T, Schultz G, Breer H, Boekhoff I. Selective activation of G protein subtypes in the vomeronasal organ upon stimulation with urine-deprived compounds. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4655–4662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Dudley C, Moss RL. Functional dichotomy within the vomeronasal system: distinct zones of neuronal activity in the accessory olfactory bulb correlate with sex-specific behaviors. J Neurosci. 1999;19(RC32):1–6. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-j0003.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman ER, Corey DP. Electrophysiological characterization of chemosensory neurons from the mouse vomeronasal organ. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4625–4637. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-15-04625.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman ER, Corey DP, Dulac C. TRP2: a candidate transduction channel for mammalian pheromone sensory signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5791–5796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Lu S, Chen P, Wang D, Halpern M. Identification of chemoattractant receptors and g-proteins in the vomeronasal system of garter snakes. J Biol Chem. 1994;24:16867–16877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunami H, Buck LB. VNO-related receptors in zebrafish [abstract] Chem Senses. 2000;25:678. [Google Scholar]

- Neer EJ. Heterotrimeric G proteins: organizers of transmembrane signals. Cell. 1995;80:249–257. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez I, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P. Variable patterns of axonal projections of sensory neurons in the mouse vomeronasal system. Cell. 1999;97:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80730-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers KE, Dasgupta P, Gubler U, Grillo M, Khew-Goodall YS, Margolis FL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1704–1708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.6.1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryba NJ, Tirindelli R. A novel GTP-binding protein gamma-subunit, G gamma 8, is expressed during neurogenesis in the olfactory and vomeronasal neuroepithelia. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:6757–6767. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.12.6757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryba NJP, Tirindelli R. A new multigene family of putative pheromone receptors. Neuron. 1997;19:371–379. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80946-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatas T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Scalia F, Winan SS. The differential projections of the olfactory bulb and accessory olfactory bulb in mammals. J Comp Neurol. 1975;161:31–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.901610105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman N, Erichsen F, Halpern M. Garter snake response to the chemoattractant in earthworm alarm pheromone is mediated by the vomeronasal system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;510:330–331. [Google Scholar]

- Segovia S, Guillamón A. Searching for sex differences in the vomeronasal pathway. Hormones Behav. 1996;30:618–626. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1996.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DC, Hrapchak BB. Theory and practice of histotechnology. Saint Louis: C.V. Mosby Company; 1973. pp. 175–176. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd GM. Neurobiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara H, Asano T, Kato K. Differential localization of G-proteins Gi and Go in the accessory olfactory bulb of the rat. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1275–1279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-04-01275.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takigami S, Mori Y, Ichikawa M. Projection pattern of vomeronasal neurons to the accessory olfactory bulb in goats. Chem Senses. 2000;25:387–393. doi: 10.1093/chemse/25.4.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Treloar H, Kalb RG, Greer GA, Strittmatter SM. Go protein-dependent survival of primary accessory olfactory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14106–14111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi M, Kashiwayanagi M, Kurihara K. Intracellular injection of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate increases a conductance in membranes of turtle vomeronasal receptor neurons in the slice preparation. Neurosci Lett. 1995;188:5–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11379-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi M, Kashiwayanagi M, Kurihara K. Intracellular dialysis of cyclic nucleotides induces inward currents in turtle vomeronasal receptor neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1239–1246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-03-01239.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi M, Wang D, Halpern M. Chemosensitive conductance and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced conductance in snake vomeronasal receptor neurons. Chem Senses. 2000;25:67–76. doi: 10.1093/chemse/25.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotier D, Døving KB. “Anatomical description of a new organ in the nose of domesticated animals” by Ludvig Jacobson (1813) Chem Senses. 1998;23:743–754. doi: 10.1093/chemse/23.6.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wekesa KS, Anholt RRH. Pheromone regulated production of inositol-(1,4,5)-trisphosphate in the mammalian vomeronasal organ. Endocrinology. 1997;138:3497. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.8.5338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winan SS, Scalia F. Amygdaloid nucleus: new afferent input form the vomeronasal organ. Science. 1970;170:325–344. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3955.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu E, Tirindelli R, Ryba NJP. Evidence for different chemosensory signal transduction pathways in olfactory and vomeronasal neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;220:900–904. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki CJ, Meredith M. The vomeronasal system. In: Finger TE, Silver WL, editors. The neurobiology of taste and smell. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshihara Y, Kawasaki M, Tamada A, Fujita H, Hayashi H, Kagamiyama H, Mori K. OCAM: a new member of the neural cell adhesion molecule family related to zone-to-zone projection of olfactory and vomeronasal axons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5830–5842. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05830.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]